Johnny Mercer used to say that he wrote those heart-piercing lyrics for “One for My Baby (and One More for the Road)” on a napkin at the bar of P. J. Clarke’s. “I’m feelin’ so bad / Wish you’d make the music pretty and sad.” A famous New York character named Tommy Joyce was the bartender there, and when the song became a hit, Johnny said he called him to apologize for writing, “So set ’em up, Joe.”

“Sorry, Tommy,” he said. “I tried but just couldn’t get your name to rhyme.”

(Try it yourself—Tommy is a tough one to rhyme.)

Johnny was born in Savannah, Georgia, to a prominent Georgia family that included Revolutionary War heroes and a Confederate general. His parents noticed that he loved music at an early age and took him to see minstrel shows and vaudeville troupes. But growing up in Savannah in the early twentieth century, Johnny heard the music that nourished jazz and the blues in the cries of street vendors and fishermen, singing in southern dialect. He was enthralled.

Johnny began to write songs, the kind of ditties and doggerels that kids will do, but with a jazz beat, when he went away to his southern prep school. He was supposed to go to Princeton—several generations of Mercers had—but his family was hard hit by the financial collapse of 1929.

So at the age of nineteen, he moved to New York. He did odd jobs by day and wrote and played music at night.

His first real break came in 1933, when he worked with the great song composer Hoagy Carmichael. Hoagy told interviewers that he was napping on the sofa in his New York studio when Johnny strolled in to begin their day at the piano.

“Hoag,” he said Johnny told him, “I’m going to write a song called ‘Lazy Bones.’” And then they did, in about twenty minutes.

Johnny said he’d always resented the “southern” songs New Yorkers wrote, which he found unreal and a little insulting. He and Hoagy wanted “Lazy Bones” to convey the swelter and tempo of the South in summer, so Johnny wrote:

Lazybones, sleepin’ in the sun,

How you ’spect to get your day’s work done?

The song was a huge hit just a few days after it was played on the radio. It was a southern song that had resonance in the North, East, West, and everywhere. What parent hasn’t sung at least a few bars of “Lazy Bones” to try to get a child out of bed for school?

On the strength of that hit and a few more promising songs, Johnny moved out to Hollywood. It turned out to be the best thing for him. Movies were beginning to replace stage shows and revues, and close-mic recording techniques made lyrics more important than ever. Johnny’s lyrics were clever, sly, and worth hearing.

Johnny won a reputation in Hollywood when he wrote both the music and the lyrics for “I’m an Old Cowhand (from the Rio Grande),” for a film called Rhythm on the Range. The film starred Bing Crosby and the great Frances Farmer. It was the only “western” Bing ever made, but he plays a citified rodeo cowboy who croons:

We know all the songs that the cowboys know

’Bout the big corral where the doggies go

We learned them all on the radio . . .

It’s still a wonderfully tuneful, witty and original song (although I’ve never recorded it—I’m not sure I could keep a straight face). Rhythm on the Range practically invented the “singing cowboy” genre. In fact, watch the song in the film: you’ll see the young Roy Rogers, singing behind Bing and Frances in the chorus, and Louis Prima, who was an even more improbable cowpoke than Bing, playing the trumpet.

Johnny began to write great songs with Richard Whiting, including “Too Marvelous for Words” and the fabulous standard “Hooray for Hollywood” (a song with twenty true quotable lines, including “Hooray for Hollywood / Where you’re terrific if you’re even good”). After Richard died, too young, Johnny worked with the great Harry Warren and got his first Oscar nomination in 1938 for “Jeepers Creepers.” They would go on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song with “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe” in 1946.

Soon thereafter, Johnny began to work with the elegant Harold Arlen. Their songs began to set a new standard, including “Blues in the Night” and “One for My Baby” in 1941 and “Come Rain or Come Shine” in 1946. Their music was distinguished by a wise, sultry quality. They were songs for the long nights of the soul. Who hasn’t had those?

The rise of rock and roll threw us all a bit. But Johnny kept working and came roaring back, winning consecutive Oscars for two of the greatest movie songs ever. He wrote the lyrics for Henry Mancini’s “Moon River” from Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961, and then returned the very next year to win for “Days of Wine and Roses.”

I’m so grateful that around that time, Johnny got a note from a fan named Sadie Vimmerstedt in Youngstown, Ohio, who told him she thought that “I want to be around to pick up the pieces when somebody breaks your heart . . .” would make great first lines for a song. Johnny thought so, too. “I Wanna Be Around” became one of my biggest hits. Sadie gave Johnny a great beginning. But only Johnny Mercer could write a line like “When he breaks your heart to bits / Let’s see if the puzzle fits so fine.”

What I think I appreciated most and learned from Johnny is the way he wrote great songs with so many gifted composers over the years. His partnership with Harold Arlen was something special and extraordinary. But he also had superb working partnerships with amazing, singular talents, including Hoagy Carmichael, Richard Whiting, Harry Warren, Henry Mancini—and Sadie Vimmerstedt, for that matter. And other composers, too.

In each case, he drew strength from his collaborators and learned something new each time he worked with them. He learned from everyone and from every project. If you’re going to make a life in arts and entertainment, that helps keep you going. It helps keep you fresh.

In 1939, Johnny wrote the lyrics to a song by Ziggy Elman. Ziggy (his parents didn’t name him that; he was born Harry Finkelman in Philadelphia) was a great trumpeter who had his own orchestra for a while but was probably best known for playing with Benny Goodman. Ziggy wrote a short song as an instrumental he worked into his show. Johnny heard the tune and was inspired to write those touching, universal lines that include one of the greatest, simplest professions of love ever: “You smile, and the angels sing.” Naturally, those last four words became the title of the song.

Ziggy never wrote another hit. He wound up, according to reports, going bankrupt and working in a music store. But the song he wrote became a number one hit in America.

Johnny died in 1976. He’s buried in Hollywood, and his tombstone reads, “And the Angels Sing.” They do. And Johnny heard their voices, took it all down, and gave me those great songs to sing.

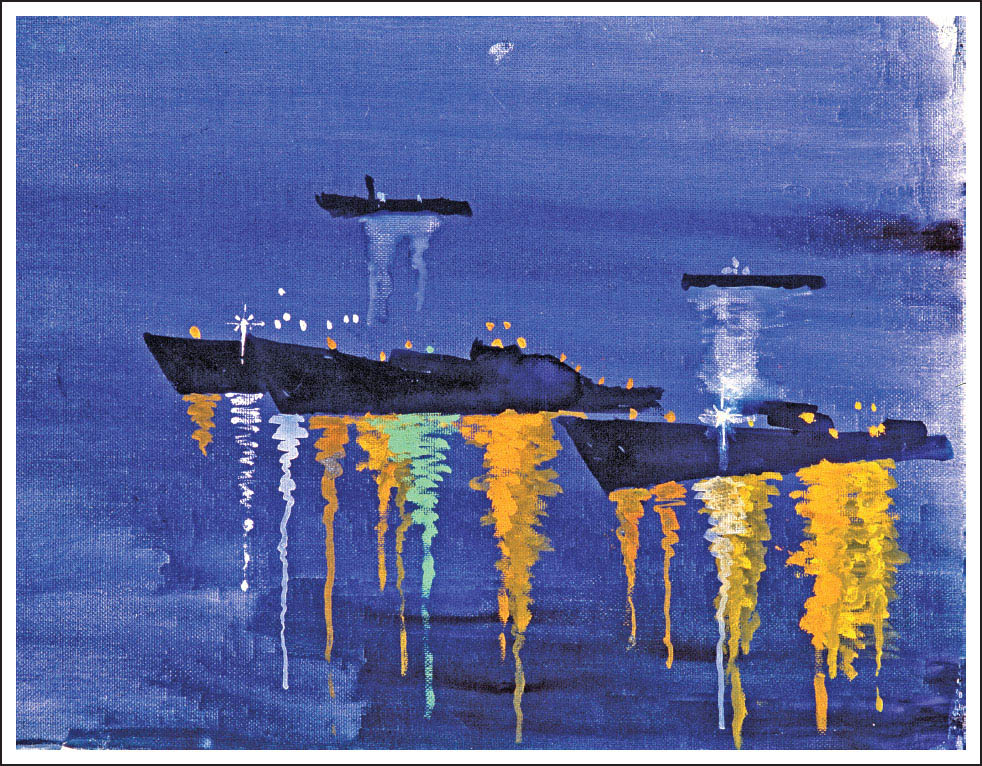

Philippine Islands, Manila