Ralph Sharon played just a few notes for me, and I knew we could make beautiful music together.

It was 1957, and I needed a new piano player. We held auditions at the Nola Rehearsal Studio in midtown Manhattan. As I remember it, Ralph was the second guy, and we didn’t have to go any further. He introduced himself, and I caught his British accent. Ralph told me he’d played with Ted Heath and His Music, the leading British jazz band, from the time he was in his late teens (though I wouldn’t learn for a few months that Down Beat magazine of England had declared him to be the Best Jazz Pianist in Britain) and had come to the United States about four years before.

“I grew up in the Tube during the Blitz,” he said. “I wanted to go somewhere I could see sunlight.”

Ralph was a tall man, beginning to bald then, with a mild smile and exquisite manners. He’d played with Carmen McRae and Johnny Hartman in the United States and said that his heart was in jazz. Then he turned around on the bench, spread his long fingers across the keys, and began to play.

I was entranced by his touch and delicacy. Within a few seconds, I knew he was the man I wanted to accompany me for all my songs, in studios and on the road.

“How’d you like to come with me?” I asked him.

“Come with you where?” asked Ralph.

“Everywhere,” I told him.

Within a few weeks, Ralph and I were in our first recording session together. Ralph loved jazz, sensed my love of jazz, and helped put the steel in my spine to stand up for the kind of music I believed in and to sing and record it.

“You can have six hits in a row,” he told me, “but if you keep doing the same thing over and over, the public will get bored and stop buying your records. If you keep singing these kinds of sweet saccharine songs like ‘Blue Velvet,’ sooner or later the ax is going to drop on you.”

So Ralph and I came up with what amounted to a formula: we’d do one record for Columbia, then one for us.

Ralph and I laid out a plan to record “The Beat of My Heart” later that year, which featured the great jazz drummers Art Blakey and Chico Hamilton, Nat Adderly on trumpet, and Herbie Mann on jazz flute. We did inventive new versions of “Just One of Those Things,” in which I sang most of the song accompanied just by Art’s superb drum work, and “Lullaby of Broadway.”

Ralph conducted all of those superb musicians, too, and though we didn’t sell as many records as “In the Middle of an Island,” “The Beat of My Heart” is now considered a classic. It signaled that I wasn’t just another crooner but a singer who loved jazz and wanted to bring its many gifts of artistry and improvisation into the music I loved. The collaborations with Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and other great names all followed.

None of that would have been possible without Ralph Sharon along. As he used to say, “I was the missing ingredient.”

Ralph was a great piano player, who would record dozens of albums on his own. But I especially treasured that he was a superb—even the perfect—accompanist. He didn’t play a melody and just expect a singer to follow. We always performed a subtle, unspoken duet, in which Ralph knew when to pull back, when to go ahead, and how to strike a note just right alongside my voice. We got better and more practiced at that over fifty years of working together, sometimes three hundred shows a year. But to be sure, we felt a lot of closeness from the first.

And of course, Ralph had the wisdom and talent to find the sheet music to “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” one night in a shirt drawer in the dresser of his hotel room in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a story told earlier in this book. That song took us around the world, in so many ways. But he always said, “If I hadn’t looked for that shirt in that drawer, it would never have happened.”

I’d only add, yes, but Ralph made sure it was in the drawer. What did Branch Rickey say? “Luck is the residue of design.”

Ralph left my side, amicably, for a few years in the mid-sixties. He still craved sunshine and wanted to live on the West Coast. He also wanted to spend more time with his family. I was lucky enough to be able to ask Torrie Zito to be my accompanist. Torrie had worked with so many great names, including Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday, and Billy Eckstine (and would go on to arrange the strings for John Lennon’s classic 1971 Imagine album). It was like getting DiMaggio to step in for Gehrig in the lineup.

Ralph did superb work with Rosie Clooney, Nancy Wilson, Robert Goulet, and many more, and liked to stay home more than he had in years. His son, Bo, liked to recall that when he finished a gig at the Hollywood Bowl or some other glamorous venue, where big stars would come backstage and want to meet him, Ralph would just say to his family, “C’mon, let’s get dinner and go home.” Nothing was more important to Ralph than his family, his wife, Linda, and his son, Bo.

But I was so pleased when Danny Bennett, my son, essentially took over my career years later and asked Ralph to come along, too. It was at least the second time Ralph took a chance on me. My career had hit some deep skids in the 1970s, and Danny told me that I would come back only if I was willing to stop making compromises, sing what I loved, and let young audiences see that I was authentic and uncompromising. It reminded me of what Ralph had said. Once again, he rode shotgun for me.

I suppose that over fifty years of performing together, there is no one I have thanked more than Ralph Sharon. He deserves even more. He won scores of awards: Grammy Awards; the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors Gold Badge of Merit; and so many more. But he barely seemed to notice the honors that piled up, and he played into his nineties.

In 2001, years after he had “retired” to Boulder, Colorado, when he was almost eighty, he still played gigs, including at teatime at the fabulous old St. Julien Hotel. Sometimes jazz lovers would see his name on a card in the hotel and say, “You know, you have the same name as a really famous pianist.” Ralph would just smile and say something like, “So I hear.”

I’m still inspired and guided by what Ralph told me so many years ago, in so many words: keep growing, and believe in what you do. I lost a real brother when Ralph passed away in 2015. I hope to keep going for a while. But it’s nice to know that when my time comes, Ralph and I will accompany each other.

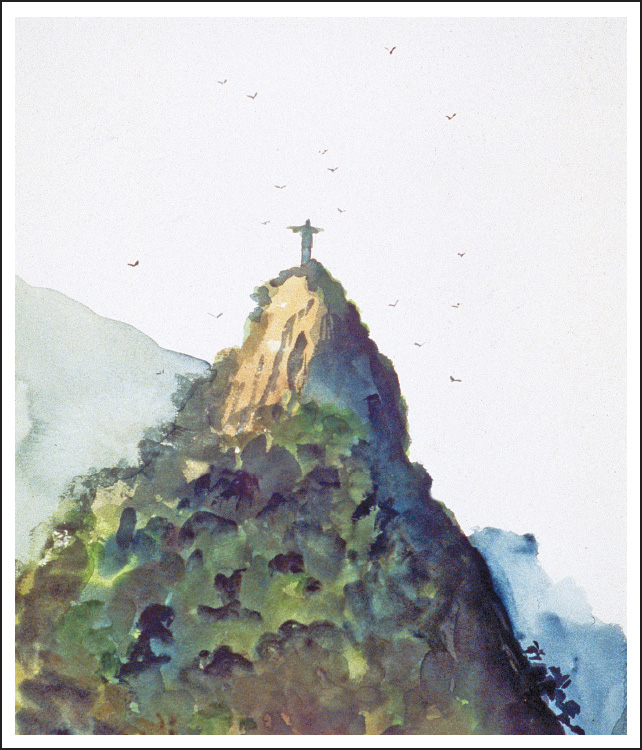

Rio de Janeiro

New York Still Life