I think Bill Basie was the greatest bandleader in American music. A bandleader is a different cat than a symphony conductor. A bandleader has to take a group of musicians who are soloists, by experience and temperament, and turn them into a band with one beating, swinging heart, while giving each of the players a featured turn.

It’s art and it’s chemistry. It’s as if a baseball team had Babe Ruth, Joe DiMaggio, and Derek Jeter, but all at once. Sounds like an unbeatable lineup—but not if they can’t be led into how to play together. And not if you can’t tell Babe, “You still get to swing away.”

Year after year, Bill Basie had Lester Young and Herschel Evans on sax, Buck Clayton and Harry “Sweets” Edison on trumpet, Jo Jones on drums, Benny Morton and Dicky Wells on trombone, and a roster of great singers that included Joe Williams, Helen Humes, and Billie Holiday. The Count’s unique, wizardly touch was to blend those artists in a way that showcased each player’s unique, extraordinary gifts.

Lester Young, who hung nicknames around people like prize medallions, called Bill Basie “Holy Man.”

I guess I’d dreamed of working with Bill ever since I heard his “One O’Clock Jump” just before I went off to war. Then I came back, started singing in clubs, and saw COUNT BASIE AND HIS ORCHESTRA on one marquee after another up and down 52nd Street while I tried to break into the business. In 1958, I finally got my chance.

I was with Columbia Records, and Bill was with Roulette Records. I would need Columbia’s approval to make a record with Bill, on his label or ours. Mitch Miller, with whom I had plenty of disagreements when he was head of Columbia, said, “What do you want to work with a junk label like Roulette for?”

The answer, of course, was that I’d do anything to work with Bill Basie.

But the companies which had us under contract couldn’t have been more different.

Columbia was the class act of the recording industry. It was the label Frank Sinatra built. Mitch Miller lured Frankie Laine from Mercury and signed Doris Day, Rosemary Clooney, Johnny Mathis, the Four Lads, and, I’m pleased to say, me (and soon thereafter, the great Miles Davis). Columbia put out the Columbia Masterworks albums under Goddard Lieberson, which included all the great Broadway shows of the time (West Side Story and My Fair Lady became huge best sellers). It was the label of classical stars that included Leonard Bernstein, Eugene Ormandy, Glenn Gould, Aaron Copland, and Igor Stravinsky.

Columbia’s engineers were the leading innovators of audio. They devised the LP, so you could play an entire movement of a symphony on one side (or, as with Columbia’s 1946 The Voice of Frank Sinatra, a “concept album” of songs grouped around a theme). It transformed the recording industry artistically and commercially.

Columbia’s 30th Street recording studio had once been a church, and it became regarded as holy ground for the recording industry. Glenn Gould recorded his Goldberg Variations there and Vladimir Horowitz his entire Masterworks discography. Miles Davis wouldn’t record anywhere else.

Bill’s label, Roulette Records, was another kind of story in the music business. A guy named Morris Levy founded the label as part of a front for the Genovese crime family (Morris would finally be convicted of extortion in 1986; he died before serving any time in prison). He did sign some great stars for Roulette, including Count Basie, Pearl Bailey, Ronnie Hawkins, and Dinah Washington and—I’ll say this for him—gave them creative freedom.

But Morris Levy exploited his stars, including Bill Basie. He signed many of them to long-term contracts at low wages (when a company is mobbed up, any offer that lets you keep your neck sounds like a bargain) and hid their money behind intricate accounting tricks. Tommy James of Tommy James and the Shondells said Morris Levy bilked their group out of at least $30 million.

Bill Basie liked to gamble. But Morris didn’t try to get him help; he just got him in deeper. He paid off Bill’s debts to gamblers, who were usually also mobbed up, and in exchange put Bill on Roulette’s payroll. Bill told me that he never earned any royalties from all those great albums he recorded for Roulette, just small checks from the company store.

Comparing Columbia to Roulette was a little like the New Yorker trying to put out an issue with a scandal sheet.

Bill and I decided to record two albums together, one for each record label. Mitch Miller was aghast and kept refusing to authorize the project. But I kept asking. Mitch had a new hit record out—“The Yellow Rose of Texas”—that was also in the classic film Giant. The week it replaced “Rock Around the Clock” as the number one hit, I decided it would be a good time to ask again. Mitch would be likely to be in a good mood.

“Go ahead,” he told me. “If you want to ruin your career.” Maybe he was even hoping for that.

Bill Basie and I had spoken only on the phone. But when we finally met in a rehearsal studio, joined by his great band, there were mutual respect and electricity. We ran through a couple of numbers, and Bill turned to those great musicians and pointed at me.

“Give this man anything he wants,” he said.

Our first recording was a live album for Columbia, recorded at the Latin Casino in Philadelphia in November 1958. It was a great room, but small. The engineers had to set up the recording console in the basement kitchen.

The recording captured the night. We had a superb collection of talents who had fun, and tried to take songs we loved to new heights. Ralph Sharon joined us on piano, and we made great versions of “Just in Time,” “Lost in the Stars,” and “Fascinating Rhythm.” The recording had crackle, sizzle, and spontaneity.

But then Columbia executives got hold of it. Stereo recording had just been developed, and Columbia wanted to show that the company was at the leading edge of technology. So the next month, they brought Bill and his band, Ralph Sharon, and me into a snug, quiet studio, where we rerecorded every single track. Later they added the crowd reaction and applause from the original Latin Casino recording to try to make the whole mixed-up bag sound “live.”

Instead, it sounded like a dud. They were using great musicians and the latest technology to try to fool people. I thought the album, which they called In Person!, fooled no one into thinking that it worked. I thought it was in bad taste.

Bill and I went into the Capitol studios in New York just a month later to record our album for Roulette. This one is much more to my liking. It was called Count Basie/Tony Bennett: Strike Up the Band, named after our opening Gershwin tune, but Morris Levy licensed the recording to so many people over the years that it’s reappeared under countless titles.

Bill’s respect for my singing helped establish me with jazz lovers and cemented an enduring friendship. He had a sly, warm sense of humor. We appeared at the White House in 1963, and during a reception we both noticed the thick, sumptuous green drapes with gold tassels. Bill lifted one of the small gold balls hanging from a tassel and muttered to me, “My tax dollars paid for this?”

Another time we played the Academy of Music in Philadelphia and the appearance was phenomenal—ten standing ovations. But Bill and I were out in the parking lot after the performance when a white man tossed him his car keys.

“Hey, buddy,” he said to Count Basie, “get my car, will you?”

I’m not sure how I would have reacted in Bill’s shoes. Would any white man? But Count Basie was a bandleader. He knew how to kid, cajole, and josh people his way.

“Get your own car, buddy,” he told the man. “I’m tired, I’ve been parking them all night.”

It was the response of a genius. The guy got his car, and the Count kept his nobility. The man never knew what a fool he was.

Bill Basie taught me how to pace a show. I’d often open with a showstopping kind of a number to get everyone on their feet, stomping and clapping.

But Bill asked, “Why open with a closer?” He thought a show could only go downhill from there.

“Start with a medium-tempo number like ‘Just in Time,’” he suggested, “and give the audiences a chance to settle in.”

Most of all, I think Count Basie showed me the value of sticking to your artistic convictions.

The era of big band music was supposed to be over at the end of World War II, and Bill disbanded his orchestra. But it was back as a sixteen-piece orchestra by the early 1950s. The era of big band music may have passed. But Count Basie’s sound and talents were in high demand, and he became the first choice of great vocalists, including Frank and Ella.

I talked to Bill during some of my most challenging years at Columbia. Clive Davis, a corporate attorney and very bright man, had been the head of business affairs at the label, and became president in 1967. He was the first guy from the business side to be appointed head of the label, and Clive’s ascension marked the moment that the businesspeople in the recording industry began to take control from the creative people. It would happen at label after label.

Clive went to the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. He came back wearing love beads and brandishing contracts with a bunch of new artists, including Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company.

Clive had a sharp eye for talent (he would soon also sign Chicago, Billy Joel, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Pink Floyd, and Bruce Springsteen) and a hard head for business. He was convinced, with the ardency of a recent convert, that only rock music would sell in the ’60s and ’70s.

My records did well and made a lot of money for Columbia. I recorded Ron Miller and Orland Murden’s fabulous song “For Once in My Life” in 1967, and it was the first time that great Motown song hit the pop charts (although I’ll be the first to admit that Stevie Wonder’s 1968 recording has made it a Stevie Wonder song for a lot of people, and I was delighted that we could record a slower ballad version together on Duets: An American Classic in 2006). I had another enduring hit the next year with my album Yesterday I Heard the Rain, which led off with that great song by the same name by Gene Lees and Armando Manzanero.

But Clive thought my refusal to record rock and pop hits kept me (and the label) from making more money. He told me I was “looking over my shoulder musically,” not keeping pace. He gave similar speeches to Peggy Lee, Lena Horne, and Mel Tormé.

Imagine telling Peggy Lee that she was “looking over her shoulder musically”!

I groused about some of those artistic stresses and regrets with Bill Basie. He also felt some of those pressures but generally resisted them. The kind of music we did had art, story, and style, he said. It moved and reached people. Thousands of people still turned out to hear his orchestra and buy his albums. Why try to be trendy when you can be timeless?

Or as Count Bill Basie asked me and I have since so often reminded myself, “Why change an apple?”

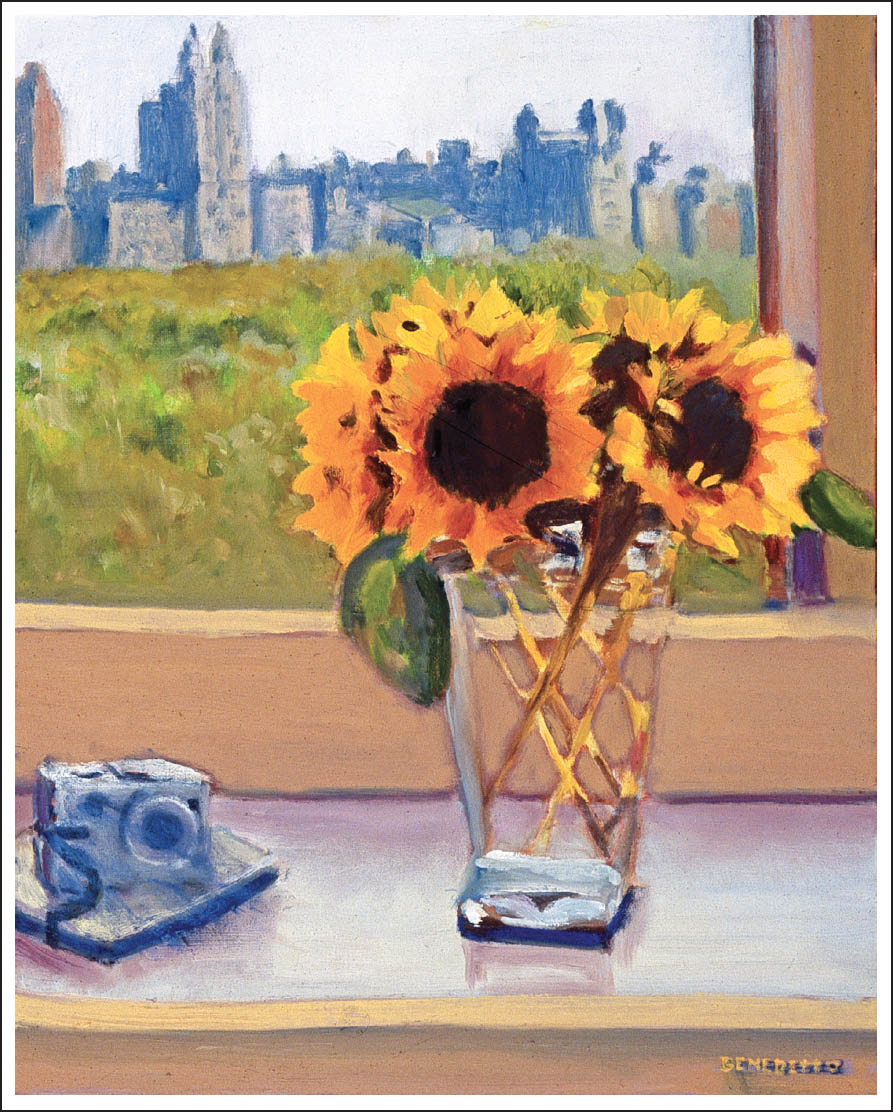

Still Life, New York, 1970