Ten Thousand Empty Stores, the Mother and Child Reunion, and the Principle of Concurrent Thinking

In 2005, I sold an online tax company I cofounded to H&R Block. My business partner became the president of the Digital Tax Division, and I became the vice president of marketing and innovation. We negotiated our deal with the CEO, Mark Ernst, and took up residence in a renovated gothic tower in downtown Kansas City. Over the next few years I watched as Block tried to develop a new business model but stumbled and failed. The failure is the perfect example of what happens when you’re strategically focused but blind to the tactical reality of your business model. It’s a common mistake, one we all have a tendency to make, but it’s also avoidable if we understand the trap that strategic thinking sets for us.

Mark began his career at American Express. After a series of promotions, he found himself the head of American Express Financial Services. In that capacity he was responsible for marketing and selling financial advice to the huge portfolio of American Express cardholders. He was recommending and selling stock, 401(k)s, and retirement planning. A few years into his tenure, another opportunity came his way: he was asked to interview for the chief position at H&R Block.

Henry Bloch, the founder and then CEO, was in his seventies and ready to retire. Henry was a true Horatio Alger characer, a classic rags-to-riches story. With his brother, Richard, who’d recently died of cancer, they’d created one of the great American companies and established one of the great American brands. Henry is the “H,” Richard is the “R,” and “Block” is the more phonetic spelling of their last name. The company had shown consistent growth nearly every year for the last four decades. This growth was the result of a very simple, yet effective tactical strategy: they just kept opening new tax preparation stores. The tax preparation business was recession-proof, and they’d developed an effective business model based on solving a very important customer problem: preparing taxes. The problem led to a hypothesis that people needed a brand they could trust to help them maximize their refund and make sure they did everything right, thus avoiding an audit. The model was based on this theory. Warren Buffett, who loved the model, was one of the primary stockholders. However, by the time Henry interviewed Mark for his job, the writing was on the wall—the strategy had been played out. There was a store in nearly every town in the country. H&R Block had more locations than McDonald’s or Burger King, almost ten thousand stores. They couldn’t open any more, at least not at the same rate they’d been doing. They needed a new strategy.

Enter Mark Ernst. The new strategy would be to expand the service offerings within those ten thousand stores. I don’t know who made the strategic decision to turn H&R Block from a “tax preparation” company into a “financial services” company, but it was done before Mark came into the picture. In fact, that’s why Mark entered the picture. Henry and the board of directors wanted someone to implement the strategy, and Mark was a great choice. Using top-down thinking, they wanted to turn their seasonal stores and seasonal employees into annual stores and their part-time employees into full-time ones. After all, they had ten thousand stores sitting empty for more than six months a year and more than 20 million loyal customers who trusted them with preparing their taxes. What would you do? It was a good idea, a logical strategy. However, it’s also one that had little or no consideration or insight from the tactical level. The strategy was conceived by the board and senior management with little or no consultation with those in the stores, those dealing directly with the customers. Exactly what customer problem, I often asked, are we solving with our new strategy? The answer was, of course, that we weren’t solving a customer problem; we were solving an H&R Block problem (ten thousand empty stores).

Over the next few years, Block constructed the new model, spending hundreds of millions of dollars. First, the company bought Option One Mortgage, making Block the third largest mortgage company in the country. Then the company bought Olde Financial, an investment-planning company, providing the corporation with another component of its financial services empire. Under Mark’s direction, Block had become a tax preparation/mortgage/investment/retirement-planning/banking company, or what Mark referred to as a “world-class financial services company.” Wall Street loved it, stockholders cheered, and the stock price continued to climb. But, like the space shuttle Challenger, it was a disaster waiting to happen.

Though the strategy was interesting, it didn’t work on a tactical level. Whereas Mark and others espoused “world-class financial services,” the customers did not. Financial services, at the tactical level, was a fuzzy idea at best. “Where are you going?” A wife might have asked her husband. “I’m going out to buy some financial services, honey. Do you need any?” “Financial services” turned out not to be an important customer problem, or not one that consumers wanted Block to solve. In the public’s mind, Block was a tax preparation company; one that solved the complex and emotional problem of preparing your tax return. It was not a mortgage company, not an investment company, not a retirement-planning company, and certainly not a financial services company, whatever that meant. The “brilliant” strategy only confused the customer. There was no such thing as a financial services problem to solve, no root cause, and so no underlying hypothesis on how to solve it. It was built on a foundation of sand. Though the executives loved the idea, we minions in the field knew it was a losing proposition. Customers didn’t get it.

After five years of little or no growth and more than $300 million in losses, and as the mortgage portfolio began to soften, the stockholders and analysts began to revolt. The stock price slipped, and a billion dollars of equity was lost. Mark was caught in the middle. The former head of the Securities and Exchange commission, who’d formed his own investment company, bought 10 percent of the company and then forced a vote of no confidence among the stockholders. Amazingly, even Mark’s own board voted against him, and Mark resigned. The new chairman told the stockholders and analysts that there was a new day dawning at H&R Block, it would be getting back to basics and becoming a tax preparation company again—instead of a tax preparation/mortgage/ investment/retirement-planning/banking company. The stockholders cheered, and the analysts loved it. It’s a brilliant new strategy, they said. The stock price began to rebound.

Top-Down Thinking

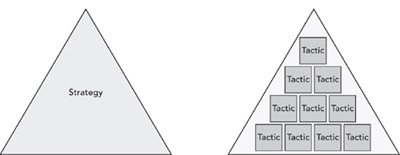

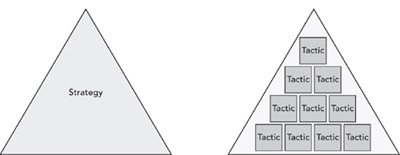

As we’ve said, strategy is what we are going to do, while tactics are how we’re going to do it, and our strategy should be clearly based on a key problem we’ve set out to solve. Top-down thinking begins with a problem and establishes goals and objectives associated with it, so we call it strategic thinking; future thinking is inherent in it. Bottom-up thinking, on the other hand, is based primarily on the here and now, on the solutions that one is already prepared to offer, and it tends not to be heading in a particular strategic direction. The danger of following only one of these approaches is highlighted by the H&R Block story. The Block financial services strategy was created with a purely top-down process, beginning with a problem in mind—utilizing ten thousand empty stores—and not sounding out those who would have to make it happen.

Taken to an extreme, without tactical thinking, strategic thinking can be disastrous. Purely strategic thinkers tend to be philosophical, idealistic, and theoretical, not good at considering tactical practicalities. This is a trap we’re all susceptible to stumbling into, especially when we reach upper management, in part because we don’t want to micromanage.

We all have a great admiration for great strategic thinkers, people who set out to solve an important problem and persevere through obstacle after obstacle. We tend to see them as big thinkers, not lost in the details and deterred by practicalities, but focused on a larger end goal. According to a recent Gallup Poll, the two most admired people in history are Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King, Jr. Both of them were big thinkers with clear strategies and grand goals, but they were also brilliant intellectuals, bottom-up thinkers. Mother Teresa fought a war against poverty by immersing herself in the ghetto and getting her hands dirty. When asked how people could help her cause, she said, “There should be less talk; a preaching point is not a meeting point. What do you do then? Take a broom and clean someone’s house. That says enough.” And though Martin Luther King, Jr., had a potent dream, he set out to fulfill it with well-elaborated methods of passive resistance. The power of a top-down goal can be very effective, but it can also lead us into a strategic trap. Goals alone do not lead to success; they are only one part of the equation. For every story of a top-down thinker becoming successful, there’s a story of another who didn’t. Top-down thinking must be tempered with bottom-up awareness. The strategic needs to be tempered with the tactical.

Bottom-Up Thinking

Bottom-up thinking is less familiar to most of us. In business, it means beginning with a successful tactic or set of them and finding your way to a strategy. It’s a common method in invention and entrepreneurship. For example, when Thomas Edison created the phonograph, it initially failed as a product because he marketed it to solve a dictation problem for business executives and as a tool for older people to record their life stories on their deathbed so that future generations could hear them. There wasn’t sufficient demand for either use. Ten years later, however, he sold the patent to an investor group, which used it to record music. Success! The phonograph was a solution looking for a problem to solve, and that problem took a decade to find. Metaphorically, the bottom-up thinker begins walking and later decides where he’s going to end up.

Bottom-up thinking requires tactical skills. Imagine someone asking you to design and construct an earth-orbiting space station. Where would you start? This was the question that NASA asked my boss, Bob Pedralia, in 1985. The process we went through to answer this question was one dominated by tactical thinking. The first thing Bob did was to break the problem into its component parts: structural, navigational, propulsion, life support, energy, and habitation. Each piece was assigned to a different team. The teams, in turn, broke their piece into its parts, the pieces into pieces. The structural team, for example, broke its components into the truss structure, the module structure, and the docking structure. The truss structure, in turn, was broken into geometry, materials, and fasteners. The fasteners grouped into welds, bolts, screws, and nuts. Each piece of the station was reduced in this way.

Bottom-up thinking as a business process is characterized by trial and error. This is actually a natural way to think. It’s how our ancient ancestors thought. In fact, nature itself creates through a bottom-up process. Take, for example, the way a river is designed. Technically, rivers are marvels in engineering efficiency, always flowing downhill, stepping down, through carefully carved canyons and valleys, until they reach their final destination (another river, a lake, or the ocean). Quite amazing. But the river isn’t designed from the top down, it’s designed by a series of bottom-up processes. The sinuous effect you see, the design, is the result of the sediment transportation process. As a river flows, it cuts into the surrounding soil and rock and picks up sediment, or pieces of sand, and carries them downstream. As it makes a turn, the outside flow of water speeds up and cuts more deeply into the riverbed, picking up more sediment, while the water on the inside of the turn slows down and deposits sediment on the inside edge. That’s why you see sandbars on the inside of a river’s turn and the fast-moving channel on the outside. Over time, this creates the river’s snakelike appearance.

The way entrepreneurs make use of the bottom-up process to create a business model is beautifully illustrated by the story of Niklas Zennström. In 2000, he and Janus Friis started a company called Kazaa. It was a peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing system that, like Napster, was used to swap digital music. A year later, Napster was shut down by the U.S. District Court for copyright infringement, and Zennström, seeing the writing on the wall, sold Kazaa for half a million dollars. Thus ended Plan A.

Zennström and Friis retreated into the woodwork and began working on the next plan. According to Zennström, “We realized that P2P, with a distribution base, could be used for lots of applications, so we decided to create the technology and build the business from there.” In other words, they didn’t have a strategy, they had only a technological tactic. Put another way, they didn’t have a problem, they had only a solution. “The question we were asking,” he said, “was how can we disrupt existing business models and create a sustainable competitive advantage?” In other words, what problem can we solve with the technology we’ve developed?

In the summer of 2002, they answered the question. They decided to use their P2P technology to solve the problem of making telephone calls over the Internet. Instead of using AT&T’s vast network of cables or Verizon’s mobile towers, customers could use the Internet to transmit and receive digital voice messages—telephone calls—and since Zennström and Friis could use the existing Internet cables and customers’ computers, the cost of building the system was minor. Six months later, they launched their solution as a way to make free telephone calls. Now, that’s a hell of an idea. They called it the “Sky-Peer-to-Peer” system, and Zennström began referring to it as “skyper” for short. Since www. skyper.com was already taken, they dropped the “r” and the new business was simply called Skype.

You need this kind of tactical thinking skills to construct a good business model. But pure bottom-up thinking, carried to an extreme, is just as impractical as pure top-down thinking. Bottom-up thinkers tend to get lost in the details and have little sense of direction, so they often don’t accomplish much. They can’t see the forest because they’re blinded by the trees. I think of pure bottom-uppers as being on a treadmill; they may be moving fast, but they don’t seem to get anywhere. Again, it’s a combination of the tactically oriented way of thinking and strategically focused thinking that is the ideal.

The Principle of Concurrent Thinking

Great strategic thinkers are always great tactical thinkers. Steve Jobs is accused of being a micromanager because he is. He’s a micromanager because he knows that a powerful strategy works only if it manifests itself in the details. Jobs will work for months, back and forth with his designers, on the button design of a new iPod. He’s a strategic thinker and can lead the company, and at the same time he’s tactically focused, getting involved in the minutiae of his corporate strategy. Walt Disney, like Jobs, was a master of minutiae who balanced this with strategic thinking. He perceived Disneyland, at the highest level, as a movie starring his customers, his employees as cast members, and his buildings as movie sets. Disneyland was created with the use of storyboards, allowing Disney to conceive his designs from a holistic point of view. This allowed him to see how the pieces would fit together, the overall impression they’d make, before he ever broke ground in the orange groves of Anaheim. He had a perfect sense of the whole and the parts, a balance between them—the ability to think concurrently. And, like Jobs and Disney, Mark Zuckerberg determines the strategic direction of Facebook while he also writes code and gets involved in every new feature of the site.

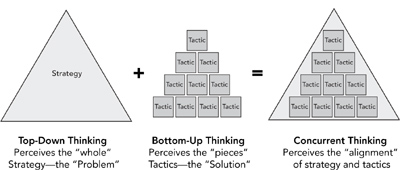

Concurrent strategic and tactical thinking is needed to construct an effective business model with well-aligned strategy and tactics. Architecture is a good metaphor for this. For an architect, strategy is structural, it provides the overall form of the building, while tactics are the material used to construct it. The Empire State Building is made of steel beams, rivets, connectors, concrete aprons, and glass windows. These components were put together to form the iconic pencil-like shape. Effective business models work the same way: the tactics are put together to form the shape of the strategy. Strategically, Facebook is a communication tool used to enhance existing relationships. The tactics—confirming friendships, the news feeds, the design layout, photo sharing, and other features—work together to make it a communication tool. Conceptually, a well-aligned model looks like this:

You have to be able to see both the trees and the forest they make up. In this way, strategy and tactics are inseparable because one is made up of the other. Thinking about them separately is like an architect conceiving the form of a building without giving any consideration to the material he will use to construct it. Materials determine the shape of the design. The Empire State Building never could have been built without the steel In beams used to construct it. Historically, as construction materials have evolved, so, too, have the shapes of the buildings an architect can create.

Without alignment, strategy is nothing more than lip service or an interesting PowerPoint slide. Yet most businesses have no mechanism to ensure alignment. They separate the strategic process from the tactical one and end up with business models that are out of whack with their stated purpose. A glaring case in point is the model NASA created with the space shuttle.

I began my career as an aerospace engineer working for the McDonnell Douglas Astronautics Company. Among other projects, I was part of the design and testing team for the solid-fuel rocket boosters used on the space shuttle. The shuttle was built to solve an important problem: providing a safe, low-cost mechanism for putting men and materials into low earth orbit. This led to a hypothesis: NASA should build a reusable launch vehicle. In other words, from a strategic standpoint, the shuttle was designed to be a low-cost “space truck.” Conceptually, it was a pretty good idea; there’s no sense building a new car every time you want to take a drive. So we built it. But on January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded a minute after liftoff. A few years later the Columbia exploded on reentry. The shuttle’s failure rate was supposed to be 1 in 100,000 launches, but its actual failure rate was 1 in 25. And it never even came close to solving the problem of low cost. The original estimated price to orbit was $5,000 per pound. However, when it finally became operational, the actual price was more like $1,000,000 per pound. Today the program is scrapped and we’re back to using Apollo-era launch vehicles.

The shuttle should never have become operational. We didn’t have the technology (the tactics) to meet the stated objectives (the strategy) of the program. It was conceived as a space “truck,” but it wasn’t built of truck parts. It didn’t have the redundant systems you’d find in a Mack truck or Boeing commercial airliner. Our designs had very little margin of error engineered into them. That’s the way you design a spaceship, not a truck. Hell, a truck doesn’t blow up if its fuel pump malfunctions. And it turned out that the stresses created by a rocket ship are so severe and violent that it’s dangerous and expensive to reuse it. The cost of inspecting and then fixing the shuttle after every flight was almost more than the cost of building an Apollo-like launch vehicle from scratch.

Early in the program, in the testing phase, it became apparent that it wasn’t going to meet its low-cost objective, but instead of adapting—either developing better tactics or scrapping the program altogether—NASA continued to build it. The shuttle was a high-end rocket ship cleverly disguised as a low-end reusable space truck, a disguise that fooled even the people who worked on it. It fooled me. It was misaligned, but we couldn’t see that through the rhetoric. If we had looked at it conceptually, it would have looked like this:

In principle, strategic alignment is simple, especially when we think of strategy as the problem and tactics as the solution. However, it is more difficult in practice, and a big reason for this is that any model is really solving multiple problems. That’s why, again, it’s important to rank the importance of the problems your model is designed to resolve. Apple has both usability problems and industrial design problems to solve. Sometimes solving them is mutually exclusive, as in deciding whether to use a mechanical or touch screen keyboard, and so the business must decide which problem is more important—design or usability? Sometimes their solutions are not exclusive, as in creating icons to denote different applications; many different ones look cool, and they are easy to use and understand.

The Mother and Child Reunion

But the age-old question is, what comes first, strategy or tactics? In 1972, Paul Simon, of Simon and Garfunkel fame, released his first solo album. The first hit single from it was a haunting song with acutely cryptic lyrics. It was called “Mother and Child Reunion.” Some listeners believed that it was about a woman who fatally loses her child and is reunited in an afterlife (one line refers to the danger of “false hope”). In a Rolling Stone interview, Simon was asked about the deep hidden meaning and the inspiration of the popular song. He said, “You would never have guessed. I was eating in a Chinese restaurant downtown. There was a dish called “Mother and Child Reunion.” It’s chicken and eggs. And I said, “Oh, I love that title. I gotta use that one.” Today, you can still find it on the menu at the Say Eng restaurant in Chinatown in Manhattan.

When it comes to business development, we need a mother and child reunion, yet even specialists on strategic and tactical thinking can struggle with this. Wayne Hughes is a senior lecturer and military theorist at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He says that “at the most fundamental level, it is accepted that the strategist directs the tactician. The mission of every battle plan is passed from the higher commander to the lower. There is no more basic precept than that, and no principle of war is given greater status than the primacy of the objective.” First Robert E. Lee draws up the battle plans, and then his field commanders figure out how to implement them.

We can conclude that Wayne thinks that the chicken comes first, that strategy dictates tactics. Well, not exactly. For he also says, “This is not the same as saying that strategy determines tactics and the course of battle. Strategy and tactics are best thought of as handmaidens, but if one must choose, it is probably more correct to say that tactics come first because they dictate the limits of strategy. Strategy must be conceived with battle in mind.” For us, Hughes is merely saying that the materials determine the design; the shape is determined by the components we use to make it.

So the answer to the chicken-and-egg problem is simple: It doesn’t really matter what comes first. What matters is that we don’t separate the chicken from the eggs, the strategy from the tactics, or the form from the components that make it up. As we develop our plans, we must shift our viewpoint, looking at our business model from both the strategic standpoint and the tactical, back and forth, making sure that things align. We must strive to think more like Mark Zuckerberg as he created Facebook than like the NASA program managers as they created the space shuttle. The right approach can be represented this way:

Of course, it’s a little unfair to compare the evolution of Face-book with the evolution of the shuttle. Besides the obvious difference in complexity, Facebook has the advantage of being able to quickly and inexpensively launch new features, get feedback on them, and then make adjustments to them. NASA doesn’t have this luxury; its planning process is measured in decades, while Facebook’s is measured in months, days, and sometimes hours. But that doesn’t change the fact that alignment is vital; it only makes it easier to do. In fact, the story of the Apollo program is a great example of how even with a highly complex project, alignment is possible. The Apollo program began with a top-down way of thinking but incorporated bottom-up processes. It started with the mother but eventually reunited it with the child.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first man-made satellite, Sputnik. It was a metallic sphere about the size of a beach ball that was launched from a converted ICBM. It stayed in orbit for about three months and emitted radio signals that were picked up by amateur radio operators throughout the world. It shocked the United States. A few years later, we were rocked again when the Russians successfully put the first man into space, Yuri Gagarin. The space race was on, and the Soviets were out in front.

In 1961, a few months after Gagarin’s flight and less than a month after Scott Carpenter became the first American in space, President John F. Kennedy proclaimed, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” With those words, the strategic planning process began. It was clearly a top-down beginning. Kennedy identified an important primary problem, putting a man on the moon, as well as a secondary one, returning him safely. When he said that, there were a few theories about how to do so, but the technologies to make it happen didn’t exist. And so it was a very bold objective.

The Apollo program, as it was later called, became the largest commitment of resources ($25 billion) ever made by any modern country in peacetime. At its peak, it employed 400,000 people and required the support of more than 20,000 industrial firms and universities. It was a planner’s nightmare.

Once the problem was identified, Kennedy established a committee of high-level technical executives, headed by Robert Seamans, to develop a hypothesis for solving it and the corresponding tactics needed to do so. At first, Seamans defined three possible mission scenarios, three possible plans, three different tactical solutions. The first was the “direct ascent” plan, which called for a spacecraft that would travel directly to the moon, landing and returning as a unit. The second was the “earth orbit rendezvous,” which called for assembling a direct-ascent vehicle in low earth orbit through multiple rocket launches (similar to how we built the current space station). The third was the “lunar surface rendezvous,” which called for two spacecraft launched in succession. The first spacecraft would make an unmanned landing on the moon and contain fuel and oxygen. The second would be a directascent manned craft, and when it landed on the moon the fuel and oxygen would be transferred to it for the return flight home. Each of the options required new technologies, new subtactics, to be developed before implementation.

The committee debated the three different solutions for months. However, at the same time, in an office at the Langley Research Center in Virginia, a low-level aerospace engineer came up with a fourth idea, a different option, which he called “lunar orbit rendezvous.” John Houbolt’s idea called for a single spacecraft composed of modular parts. The command module would remain in orbit around the moon, while a lunar module would descend to the surface and then return to dock with the command module while it was still in lunar orbit. The beauty of this idea, he explained with great passion, was that, as opposed to the other ones, it could be built using existing rocket technologies. In other words, the tactics for his solution already existed.

Ultimately, as you may know, Houbolt’s plan was chosen, a strategic decision that saved billions of dollars and precious time by using existing technologies. The space historian James Hansen said, “Without NASA’s adoption of this stubbornly held minority opinion in 1962, the United States may still have reached the Moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplished by the end of the 1960s, President Kennedy’s target date.”

There are two things to be learned from this story. The first is that the Apollo program is a great example of building a model that begins with a top-down process. The second is that the search for a solution was open to bottom-up, tactically based problem solving. Instead of going through the proper NASA chain of command, Houbolt sent a series of memos and reports directly to Seamans, infuriating his bosses. However, to Seamans’s credit, he listened and presented this fourth option, which was summarily rejected at first but finally adopted for the simple reason that it was constructed of proven technologies. Seamans had the ability to think concurrently. Later NASA would lose its way, forget about strategic alignment, and fool itself into thinking it was building a truck and not a spacecraft. This was due to a shift in how the organization was managed.

Put simply, NASA evolved into an organization strongly dominated by upper management. Richard Cook, a resource analyst at NASA and the author of the book Challenger Revealed: An Insider’s Account of How the Reagan Administration Caused the Greatest Tragedy of the Space Age, described the reorganization of the agency as clearly strategic and not tactical. He said, “Top-down ‘management by objectives’ and its derivatives were the result.” In contrast, during the Apollo program, the astronauts themselves were part of the strategic planning process. Deke Slayton, an Apollo astronaut, reported directly to the head of the Johnson Space Center. He said, “We had a very strong voice directly into the engineering system. Management listened to us. We had the ability to delay launch if we weren’t comfortable with things, and we did.” The shuttle astronauts, on the other hand, had no such input; the decision to launch was solely a management one. That proved fatal.

The night before the Challenger catastrophe, as the temperature on the launch pad plunged below freezing, Mike Smith, the Challenger pilot, told a friend, “You know, you’ve got people down here making decisions who’ve never even flown an airplane before.” In other words, you’ve got people thinking top down, strategically, with little understanding of or concern for the tactical applications. Cook explained it like this: “One characteristic of a top-down, command-and-control organization, is that an ordinary person in the system can never talk to the managers directly.”

Of course, this begs the question, how do I ensure alignment?

Strategic Alignment Through Tactical Briefings

In order to facilitate alignment, adaptive managers should develop a series of tactical briefing documents. These documents will be the “marching orders” for those responsible for the implementation of tactics.

Similar to the creative marketing briefs used by advertising agencies, these documents are used to coordinate the execution of tactics and to make sure that strategy and tactics are consistent. They allow upper management more visibility into and control of the execution of the strategy. They should be used to coordinate the work within the business units and to better define roles and responsibilities.

Tactical briefs should be written for each specific tactic; including a description of the goal of the tactic, the market segment targeted, the competition, the primary and secondary messages, the schedule, and roles and responsibilities. At Wal-Mart, management doesn’t want to initiate a tactic that may drive up the price of the products on the shelf. Any tactic that reduces price, or is neutral, is one consistent with the problem the company is solving. Facebook doesn’t want to initiate a tactic that will reduce the effectiveness of the site as a communication tool. And NASA didn’t want to design a component that would increase the overall launch cost of the shuttle.

I’ve used this technique at various Fortune 500 companies and it’s very effective at making sure that a company executes in a strategic way.

Also vital to creating an adaptive business model is articulating a specific set of goals and objectives that allows us to evaluate how the strategy and tactics we’ve aligned are working. This assists us to see, in the heat of battle, the ways in which our strategic plan might be failing and to identify the right adjustments to make. We’ll turn to this process next.