Ernest Hemingway, Writing as Thinking, Ambience Candles, and the Principle of Paper Plans

You’re not putting your written plan down on paper for your venture capital partners, for the manager you report to, for the CEO, or even for the board of directors. You’re doing it for yourself. You’re doing it to educate yourself and as a tool for better understanding your market and your business model, and for turning it into reality. Having an idea is one thing; implementing it is another.

It’s the act of planning, of putting it together, that’s going to educate you. Business is, after all, very complex. Not unlike the Normandy invasion, there are a lot of working pieces that need to fit together. The act of writing a plan will help you see the holes in your logic and coordinate all of the different elements that have to come together, forcing you to make sure that they do, and do so with strategic alignment. You may think you have a good understanding of your business, but you won’t really know until you put it down on paper. Have you ever read a court report, a transcript of a conversation, or even a screenplay? They’re hard to follow. It’s the act of writing that forces you to structure your thoughts.

Ernest Hemingway once said that good writing is merely a reflection of good thinking. People who have a difficult time writing, I’ve discovered, generally also have a hard time structuring their thoughts. Thoughts are not naturally arranged; they come in bursts, single packets of information that are electrochemical impulses in your brain, and they tend to be isolated, unconnected.

So let’s get a picture of what a good plan looks like. I put together the following plan for a company interested in developing a business model for selling candles online. The names have been changed to protect the innocent, and the actual plan was much more complex than this. I’ve simplified it so that you can get a sense of it, but even so it is still complex.

An Online Candle Business Plan

Imagine that we work for a company, Ambience Candles, that makes candles. We sell them through traditional retail shops at malls, gift shops, and large department stores. Sales are flat, and we’re looking for ways to grow. We decide that there’s a big opportunity to develop online sales. This is our plan for doing it. I would consider this a moderately complex model, and, as you read this plan, take note of how I’ve incorporated the principles of planning into it, the multiple problems we are trying to solve, and how we align the tactics and strategy.

There are five basic parts to a plan. Depending upon the complexity, you may want to add sections, but I would always have, as a minimum, these six sections:

1. Overview. A summary of the plan. It helps you and the reader get grounded and understand where we are going.

2. Background. A discussion of the market, predictions about the future, notes about the customer and notes about the competition.

3. Strategy. Identification of the customer problem. A hypothesis about solving it. And a set of high level goals and objectives.

4. Tactics. A list of the specific things we are going to do to solve the customer problem. This will include frequent referrals to strategic alignment.

5. Business model. A spreadsheet of the strategy and tactics that describes the business model. Identifies the critical metrics.

6. Implementation plan. The dashboard. Setting goals with time frames. And defining an extensive testing program.

There are currently 20 million individual searches per month on Google for candles and candle-related terms. This is a huge amount of traffic that convinces us that there’s a big opportunity for online sales. Our objective is to build a model, using a series of tactics to turn these searches into customers. Our model comprises two parts: an acquisition program and a retention program. Our business will be based on solving a compelling customer problem: creating an intimate home experience. We believe we can solve this problem by creating a deeper and more intimate relationship with our customers, becoming part of their family. This is difficult to do with our current retail sales model (our retailers control that relationship). Our solution will include creating a Candle of the Month Club and making it easy for customers to reorder from us.

The candle market experienced significant growth from the 1990s well into the mid-2000s. By 2006, according to Business Wire, the market peaked with revenues of $2.3 billion. It is a highly fragmented market with no clear market share or brand leader. While Yankee Candle peaked at $200 million, that’s still less than 10 percent of the total market (and Yankee sells more than just candles). There are problems in the industry because of low-cost alternatives and lack of brand distinction. Also, the high-end segment (luxury and true home decor items) is the only one showing growth.

The largest segment of candle users is what we’ll call the “home architect” group. These are women between the ages of twenty-five and forty-five. They’re working mothers who have a passion for design and creating an ambience for their homes. Candles are part of this ambience. They solve an aesthetic problem by providing both a visual and an aromatic experience. This background leads us to a hypothesis: we believe we can develop a “high-end brand” in the market and provide low cost by cutting out the middleman (retail markup is 100 percent in most cases). We believe there’s a great potential for the business because of the market data we discussed earlier in this proposal:

• The high-end segment is growing (helps to drive average sales price, or ASP).

• Each candle buyer spends nearly $300 per year on candles.

• Each candle buyer buys once a month (helps to drive frequency).

• Candle buyers are very brand-conscious (although not in the candle market yet).

These homemakers are very frugal while also being brand-conscious. They’re Target-like shoppers, wanting to get an item that is low-priced but with high aesthetic value. As noted, each of them spends an average of $300 per year on candles, or about $75 every three months. An online model is perfect for solving these problems. This is the same thing that Zappos did for shoes and Amazon.com did for books and other items: both provide a premium experience at a reduced rate because they sell direct to the customer.

We believe that none of our competitors is thinking this way and it will become a defendable space, though, over time, it will become more competitive, especially as our competitors get wind of our success and try to copy us.

The current online market is being driven by a combination of large online retailers such as Wal-Mart and Target and smaller online gift shop sites. The large retailers are focusing on low price, while the online gift shops seem to be presenting candles as one in a range of gift ideas that includes things such as flowers, chocolates, and stuffed animals. No one appears to be specializing in designer candles. We believe we can create a strong customer base through a focus on quality candles and still play and win the low-price game.

(Note: in the actual business plan we would go into much more depth on the market, the targeted customer [often detailing the different segments], and each of the competitors [defining their strengths and weaknesses and what problem they seem to be focused on solving]. But you get the point, right?)

Our strategy is based on solving the primary customer problem: creating an aesthetic mood for the home. We’ve developed a new product line designed specifically to solve this problem, based on acquiring designer candles at low cost. Our business model is made up of two distinct parts: (1) an acquisition program and (2) a retention program. The objective of the acquisition program is to identify our targeted customers (“home architects”) through free or reduced-price offers with a Google pay-per-click (PPC) campaign. Once identified, we will market directly to them, developing a one-on-one relationship with each customer. Our profits will come from repeat business, not the acquisition of new customers. In fact, as you will see in our model, we can lose money on acquisition and make it up on retention. Think of the acquisition program as a “shotgun” approach, while the retention program is the “rifle” approach.

The primary goal of the acquisition strategy is to attain new “home architect” customers—those who will purchase $300 worth of candles per year. It may cost us $25 per customer to get the first order, but we are confident the investment will pay off because we know, through extensive testing, the percentage of customers who are likely to purchase additional products from us. We are thinking in terms of customers’ “lifetime value.” This strategy translates into two distinct goals for this part of our model:

Goal 1: Acquire “home architect” customers at a loss of $25 per order and create a database of those customers.

Goal 2: Be the low-price leader in designer candles.

If we can achieve these goals with a Google pay-per-click campaign, we will have created a powerful acquisition method for our retention program. We feel this is achievable because our market analysis says that the competitors on Google are merely cutting their margins as they compete on price, not selling candles at a loss. Because our model is based on lifetime value, we can compete on low price because we always can sell at a loss, but only if we can achieve the objectives of our retention program.

The objective of the retention strategy is to convert the database of acquired customers into repeat customers. This means there are two primary metrics: a conversion rate and an average sales price, or ASP. Our objective will be to convert a high percentage and to increase the ASP over time. This is really a relationship-building strategy. The success of this program is based on the market research data that say that candle buyers are high repeat purchasers ($300 per year). However, we don’t believe that there’s strong brand equity in this space because no one has done a great job of establishing a strong one-on-one relationship with buyers. Yankee Candle has established its brand and its relationship through retail stores, but retail stores are very, very expensive and we suspect that it will be difficult for them to continue this high-cost strategy. The beauty of our retention program is that we can test our relationship building ideas at relatively low cost online, as well as through direct mail techniques, without having to make significant infrastructure investments. Put simply, this is a reorder strategy, and the good news is that we have to convert only 5 percent of our database per month in order for this program to be profitable. This leads us to the goals for the retention program:

Goal 3: Convert 5 percent of the database per month.

Goal 4: Drive the ASP to $75/order.

(Note: In this section we’ve identified the customer problem, developed a hypothesis for solving it, turned this solution into a business model, and then identified the critical goals for success. We haven’t laid out the details of how we are going to do it, only defined what we are going to do. “How” is in the next section.)

There are three sets of tactics for this business plan. First there are the product tactics, those involved in developing the product line. The next are the acquisition tactics, the things we are going to do to acquire new “home architect” customers and create a database of them. Finally, there are the retention tactics, the things we are going to do to convert the database of onetime purchasers into repeat purchasers, the “sweet spot” of our model in terms of profit.

Our product line needs to solve our identified problems. The candles need to be asthetically pleasing with designer quality while being relatively low cost. We’ve hired a well-known interior designer to help with the candle design, which will include a wide variety of scents, colors coordinated with the latest design trends, and attractive packaging that will appeal to the design-minded customer. We call this product line “The Private Spa Collection,” to evoke a sense of style that will appeal to our segment. In addition, we’ve redesigned our production line and so have reduced costs by 20 percent in order to provide competitive pricing.

(Note: The product lineup is critical to the success of this plan, and in the actual plan we’d go much deeper into product philosophy about aesthetics and how it manifests itself in the product attributes. For now, though, it’s important to note how we’ve aligned our product tactics with our strategy. We’re solving a “home aesthetics” problem, so our product needs to be a solution to this problem. In other words, we will invest heavily in the design of our products but try to reduce manufacturing costs.)

Our acquisition tactics will be based on Google’s pay-per-click model. There are two types of search results on Google, “organic” and “paid.” The organic results are the lower, left-hand results and are determined by Google crawlers using a secret algorithm; the top box and right-hand margin contain paid results, and advertisers purchase those spots through a sophisticated bidding process. The advantage of PPC is that we pay only when a prospect clicks on our link, taking her to our landing page, where we can, we hope, convert her into a customer.

The problem we’re trying to solve in the acquisition program is acquiring prospects at a loss of less than $25 per order. This problem is broken into three subproblems: keywords, text ads, and landing pages. Each of these problems has an associated metric and will have specific tactics designed to solve these problems. Let’s review each one quickly.

Keywords are the terms that the general public enters into a search engine. We’ve identified fifty such terms that we feel our “home architects” will use, such as “scented candles,” “votive candles,” “candle sets,” and “designer candles.”

(Note: Choosing the right keywords is a critical tactic. Note how we’ve aligned our strategy and tactics here, choosing words that will help solve our highest-level problem. For example, we could probably get a lot of clicks if we advertised the words “candle making,” but that would not be consistent with our strategy; it would be targeting a different segment of the market. In the actual plan, there was a lot more detail about the right keyword.)

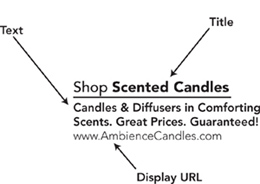

The next problem we need to solve is to get people to click on our text advertisement. There are three tactics we can use to solve this problem: (1) the title of the ad, (2) the text of the ad, and (3) the display URL (see the figure below). Once they click on the ad, it will take them to our landing page, where we will try to “close” them. Before we get to that problem, though, let’s look at how we solve the text ad problem.

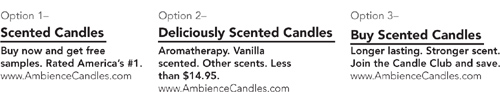

We will use some “best practices” to solve this problem. These include being clear and specific, being differentiated from the competitors, including the keyword in the title, including the price (or “free”), and including a call to action (e.g., “buy,” “order,” “purchase”). In addition, we want to align the ads with our targeted customers, so our offer should be for “low-cost designer-quality candles.” For example, here are some ads we might run (each demonstrates a different tactic):

Once we get a winner, we will hypothesize about why the advertisement worked and try to exploit our learning. For example, if Option 2 wins, we may hypothesize that including the price is what makes it effective. From this hypothesis we would then test different price levels. Once we identify winners, they will become our control, and we will test against them, looking for the next ad to beat them. In this way, we will slowly evolve our model, learn what the key drivers of our business are, and test our primary hypothesis about the home architect customer. In other words, over time we are going to be testing both our strategy and tactics.

The final part of our acquisition program is getting prospects to take our offer. This happens on the landing page. This is a page in our website designed specifically to convert these paid clicks. Right now, a number of competitors are just sending prospects to their home page, not a specifically designed page. We will design pages that are consistent with solving our primary problem and consistent with the text ad that they clicked on. We will apply best practices, such as visual appeal (having a “designer” look and feel); relevant content (the content should match the keyword; if the keyword was “scented candles,” make sure that’s what the page is about); “scannable” text (because prospects concentrate on headlines first and copy second); images (product samples); reduction of the number of clicks needed to buy; and reduction or elimination of navigation (to keep users focused).

(Note: Like the other tactics, these are solutions to the problems of converting prospects into customers. And as with the other tactics, we will strive to test different landing pages, changing the images, the products, the offers, and so on, until we can optimize for the best conversion rates. The real plan would have a lot more depth here.)

Our retention tactics are the key to this business model. There are a number of such tactics for establishing a relationship with customers that we can test. For example:

• A communication plan

• Direct mail

• Surveys

• Candle of the Month Club

• A free sample program

• A test panel program

• Volume discounts

• Gift programs

• Candle (Tupperware-style) parties

(Note: The retention program is about solving a relationship marketing problem, so we’ll strive to use “best-practice” relationship marketing techniques. At the same, we’ll strive to make sure that all of these tactics work to solve the primary problem of “creating an aesthetic mood for the home.” There’s no need for me to expand on what a Candle of the Month Club would be; you can probably imagine it yourself. The important thing to note is how we develop tactics, based on theories, and set up a number of different tests to optimize how we are going to construct our business model. We don’t choose just one tactic, we choose many. Some will work, and others won’t—and this will give us insights into our business and allow us to make adjustments that will naturally evolve Plan A into Plan B. Make sense? Good.)

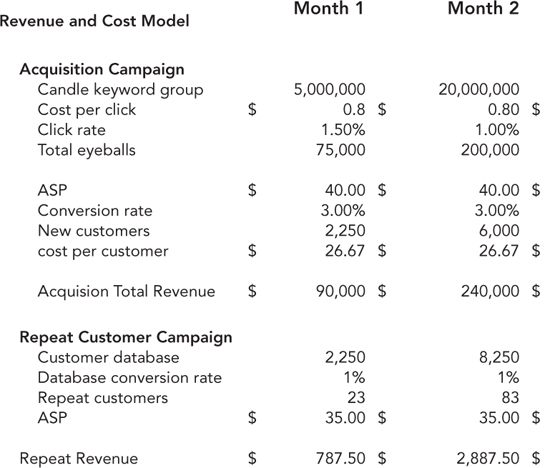

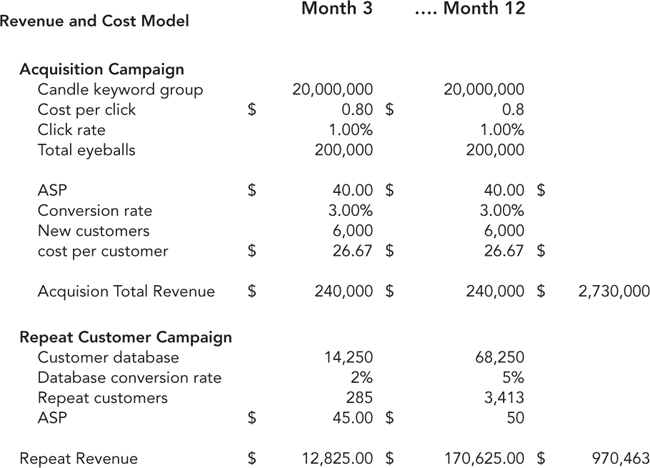

The strength of this model is our ability to control, test, and evolve the model. We will manage the program by making metric predictions, adjusting the model based upon actual results, and then making new predictions. As the model evolves, we will get an understanding of which metrics we can control and which we cannot. Here’s what the revenue and cost model looks like:

There are four key drivers of success:

• Total keywords. We can’t affect that number, it is what it is—and it’s a lot.

• Click rate. 1.5 percent is about industry average. We should be able to drive more than 100,000 eyeballs per month.

• Conversion rate of browsers to buyers. 1 to 3 percent is the industry average. At 3 percent we could acquire more than six thousand new customers per month.

• Conversion rate of new buyers to return buyers. This is the primary metric we will use to judge whether the model is working or must be adjusted.

(Note: There’s no need to study this model; it’s quite complex. What is important is that you can see how we’ve simply taken our strategy, goals, objectives, metrics, and tactics and used a spreadsheet to describe them mathematically. When you do this, it shows how everything fits together and you can begin to run sensitivity tests. For example, if you can increase the click-through rate by 20 percent, what does this ultimately mean for the program? It also helps with strategic alignment, as it helps you get a sense of how each of the tactics affects the overall business model.)

The implementation of this program will take place in steps. Since this is a new business model, we want to keep investments low while we test the viability of the program. These are the things we can do to confirm the model before we do a full rollout of this program:

1. Traffic verification

2. Click-through rate verification

3. Conversion rate verification

4. Acquisition ASP

5. Retention rate verification

6. Lifetime value of a customer

There are three checkpoints. We don’t go to the next step until we verify each of them. Here are the main ones.

• Traffic verification. Is it really twenty-two million per month? If not, what is it? Can it support an online acquisition program?

• Click-through rate verification. Can we get a .5% to 1% conversion to eyeballs to our site, and can we do it at a reasonable cost?

• Conversion rate verification. Can we turn eyeballs into paying customers? It will take us longer (another six months), to optimize and really improve conversions but we will stop after a couple of months to see if we want to proceed further.

By using these checkpoints, we can limit our investment. Once we understand these metrics, we will build out the infrastructure to support a full-blown system. At the end of six months, we will review our strategy and tactics and make a decision on the next steps to take.

(Note: The specifics aren’t important here; what’s important is that we verify the effectiveness of the model before we make any major investments. For example, if we can’t get people to click on our PPC text ads, there’s no point in developing a complex retention program.)

Putting together a plan allows you to see how all the pieces fit together. The Principle of Paper Plans tells us that a plan itself is worthless; it’s the act of planning that’s important, not the fancy report. The plan educates you and your field managers and is another invaluable tool for allowing them to make intelligent adjustments during the implementation process. But you must keep in mind that a paper plan becomes largely obsolete the moment you print it.

As you construct the plan, it forces you to think concurrently, making sure your tactics are aligned with your strategy, that one comprises the other. Putting a business plan together isn’t something you should delegate. You need to be part of the process, and that includes the writing process. Successful businesspeople are both readers and writers. You don’t need great writing skills (by skills I mean good vocabulary, sentence structure, and rhythm), but your logic needs to flow well. You’ll find that your writing skills will naturally develop the more that you do it (that’s what I’ve found—my skills for writing books have been adapted from all of the business plan writing I’ve done over the years). This is also why you need to involve most of your organization in the strategic planning process: they need to understand how all the pieces fit together, especially the piece that they happen to be working on, and how they complete the big picture or grand strategy. That way, they, too, can begin to think structurally and can adjust the component they’re working on as the business develops. A business is incredibly complex, and putting the details down on paper is a way for you to grasp the complexity and begin to make the adjustments so that your model is effectively solving the right problems.

Now you have an understanding of the principles of planning and the relationship between strategy and tactics. Trust me, you know now more about planning than most corporate planners do. I hope you appreciate the fact that even something as simple as selling candles online is complex but can be built around solving a series of problems. You can see how this plan has a number of different “subplans,” just as Operation Overlord had its subplans. This is an important principle in planning, and it also speaks to the way you can apply the lessons in this book. You don’t have to be the CEO or vice president of strategic planning to think this way. The manager in charge of the PPC campaign for our candle company could have used these same principles and approach in his department.

Hopefully, you were able to grasp the concept of strategic alignment as you read this plan, noting that even when we were working on the click-through rate, certainly a lower-level problem, we still kept referring back to the problem of creating an aesthetic mood for the home. The other important feature, something we haven’t discussed in depth, is the idea of optimization and testing of your strategy and tactics. Every business plan, not just online models, should constantly be trying new tactics, learning new things, and incorporating these lessons into the business. As we’ve already noted with the Myspace example, sometimes your underlying theory is wrong. However, if you drive your theory into tactical implementation, it will force you to confirm, reject, or adjust the theory. In other words, if you follow this process and the principles of planning, you are naturally putting together a plan destined to evolve and adapt—and that’s the key premise of this book. Got it? Good. Let’s keep going and see how the evolution of a plan works.

Because, no matter how well we think through our model, how detailed Plan A becomes, as they say in the Pentagon, no battle plan ever survives the first contact with the enemy. In the next chapter we’ll explore why this is true.