Chapter 2

Defining the Organization: Bylaws and Other Rules

In This Chapter

Knowing how to adopt, amend, and suspend your rules

Knowing how to adopt, amend, and suspend your rules

Changing your bylaws and applying them properly

Changing your bylaws and applying them properly

Keeping members informed of changes to bylaws and rules

Keeping members informed of changes to bylaws and rules

“We the People. . . .”

These famous words begin the definition of one of the greatest organizations in the world, the United States of America.

We, the people, adopted a rule early on that secures the right “peaceably to assemble.” Your right to belong to an organization is based on the agreement of everybody that assembling is a natural and sacred right, and it’s one of the first membership rules the founding fathers established. It was so important that they put it in the Constitution, making it sure to stay in force unless a large majority of Americans agree to change it. And that’s not likely to happen anytime soon.

In this chapter, I focus primarily on bylaws because this governing document establishes the real framework of your organization. My focus isn’t intended to minimize the importance of other types of rules; instead, it’s to emphasize that your bylaws are to your organization pretty much what the Constitution is to the United States of America.

Covering the Rules about Rules

C’mon now, admit it: You saw it in the Table of Contents, but you really didn’t believe that a whole chapter could cover rules about the rules. Well, this is a book about a book full of rules, so this chapter shouldn’t be a big surprise. But don’t worry — it’s not all that complicated.

When it comes to the rules about rules, one rule stands out: A deliberative assembly is free to adopt whatever rules it wants or needs, as long as the procedure for adopting them conforms to any rules already in place or to the general parliamentary law (which Chapter 1 defines).

The reason for having rules in the first place is to enable you and your fellow group members to agree on governance (that is, who your leaders are, how you choose them, when you have your meetings, and so forth), procedures for arriving at group decisions, and policy that covers the details of administration for your organization.

Without rules, you won’t last long as a group; you’ll be unable to avoid conflicts, and you’ll experience disagreements on points as basic as whether a particular assembly of individuals can really decide something in the name of the group. You won’t know for sure whether some procedure used is inappropriate for arriving at an important decision. And without a way of classifying the different rules, you’ll find yourself not knowing which rule takes precedence and when. Robert’s Rules sets up some basic classifications to help you avoid these complications.

Classifying your rules

Different situations call for different types of rules. Robert’s Rules classifies the different governance rules based generally on their application and use, and on how difficult they are to change or suspend.

Robert’s Rules classifies rules for deliberative bodies as follows:

Charter: The charter may be either your articles of incorporation or a charter issued by a superior organization, if your group is a unit of a larger organization. A corporate charter is amendable as provided by law or according to provisions in the document for amendment. A charter issued by a superior organization is amendable only by the issuing organization.

Charter: The charter may be either your articles of incorporation or a charter issued by a superior organization, if your group is a unit of a larger organization. A corporate charter is amendable as provided by law or according to provisions in the document for amendment. A charter issued by a superior organization is amendable only by the issuing organization.

Bylaws: The bylaws are fundamental rules that define your organization. Bylaws are established in a single document of interrelated rules. (I discuss bylaws in detail in the sections following this one.)

Bylaws: The bylaws are fundamental rules that define your organization. Bylaws are established in a single document of interrelated rules. (I discuss bylaws in detail in the sections following this one.)

Rules of order: Rules of order are written rules of procedure for conducting meeting business in an orderly manner and the meeting-related duties of the officers. Because these rules are of a general nature about procedure rather than about the organization itself, it’s customary for organizations to adopt a standard set of rules by adopting a parliamentary authority such as Robert’s Rules. Most of the rules in Robert’s Rules and the other chapters of this book are rules of order. Rules of order can be customized by adopting special rules of order to modify or supersede specific rules in an adopted parliamentary manual. For example, the rule of order in Robert’s Rules limiting speeches in debate to ten minutes can be superseded permanently by adopting a special rule of order providing that speeches are limited to three minutes.

Rules of order: Rules of order are written rules of procedure for conducting meeting business in an orderly manner and the meeting-related duties of the officers. Because these rules are of a general nature about procedure rather than about the organization itself, it’s customary for organizations to adopt a standard set of rules by adopting a parliamentary authority such as Robert’s Rules. Most of the rules in Robert’s Rules and the other chapters of this book are rules of order. Rules of order can be customized by adopting special rules of order to modify or supersede specific rules in an adopted parliamentary manual. For example, the rule of order in Robert’s Rules limiting speeches in debate to ten minutes can be superseded permanently by adopting a special rule of order providing that speeches are limited to three minutes.

Robert’s Rules makes an important exception to the rule that a special rule of order can supersede a rule in the parliamentary manual (whew!): If the parliamentary manual states that some particular rule in the manual can be changed only by amending bylaws, the rule in the parliamentary manual cannot be superseded merely by adopting a special rule of order. You have to amend your bylaws to change it.

Robert’s Rules makes an important exception to the rule that a special rule of order can supersede a rule in the parliamentary manual (whew!): If the parliamentary manual states that some particular rule in the manual can be changed only by amending bylaws, the rule in the parliamentary manual cannot be superseded merely by adopting a special rule of order. You have to amend your bylaws to change it.

Standing rules: These rules are related to the details of administration rather than parliamentary procedure. For example, suppose your group adopts a motion that directs the treasurer to reimburse the secretary for postage up to $150 per month, provided that the secretary submits a written request accompanied by receipts for postage purchased and a log of items mailed in the name of the organization. That policy becomes a standing rule. Motions that you adopt over the course of time that are related to policy and administration are collectively your standing rules.

Standing rules: These rules are related to the details of administration rather than parliamentary procedure. For example, suppose your group adopts a motion that directs the treasurer to reimburse the secretary for postage up to $150 per month, provided that the secretary submits a written request accompanied by receipts for postage purchased and a log of items mailed in the name of the organization. That policy becomes a standing rule. Motions that you adopt over the course of time that are related to policy and administration are collectively your standing rules.

Custom: Your organization probably has some special ways of doing things that, although not written in the rules, may as well be etched in stone on your clubhouse door. Unless your bylaws or some written rule (including the rules in Robert’s Rules) provides to the contrary, a practice that has become custom should be followed just like a written rule, unless your group decides by majority vote to do something different.

Custom: Your organization probably has some special ways of doing things that, although not written in the rules, may as well be etched in stone on your clubhouse door. Unless your bylaws or some written rule (including the rules in Robert’s Rules) provides to the contrary, a practice that has become custom should be followed just like a written rule, unless your group decides by majority vote to do something different.

Ranking the rules

When you’re dealing with different types of rules, you need to know when to follow which rule. Among the more fundamental rules, then, are rules about which rule takes precedence over other rules.

Finishing first: Charter

The charter, if you have one, reigns supreme. Nothing except a judge or the law of the land supersedes it. Fortunately, a charter is usually pretty succinct and operates like a franchise. It’s a grant of authority by the state (if your group is incorporated) or a superior organization (if your group is a constituent unit of a larger body). A charter usually lists the few conditions under which you must operate, but it usually provides for your organization to be subject to bylaws specifically tailored to your organization but which may not conflict with provisions of the charter.

Coming in second: Bylaws

Even though the bylaws contain the most important single set of rules for defining your organization and its governance, the content of the bylaws remains binding and enforceable only to the extent that it doesn’t conflict with your charter. If your group isn’t incorporated or isn’t subject to a charter, the bylaws are the highest- ranking rules of your organization. No matter what, no rules of order or standing rules can ever be enforced if they conflict in any way with your bylaws.

Because bylaws define specific characteristics of the organization itself — including (in most cases) which parliamentary authority the organization uses — bylaws are of such importance that they can’t be changed without previous notice and the consent of a large majority of your members.

Tying for third: Special rules of order and standing rules

Special rules of order and standing rules have completely different applications and uses, but they rank together as immediately subordinate to bylaws because they have one particular point in common: They comprise individual rules (each of which is usually adopted separately from the other rules in the class) based on the specific need of the organization to accomplish a specific purpose for which the rule is adopted.

Coming in fourth: Robert’s Rules (parliamentary authority)

Robert’s Rules is a parliamentary manual, and if your organization has adopted it as your parliamentary authority, Robert’s Rules is binding on your group. But it’s binding only to the extent that it doesn’t conflict with the charter, bylaws, special rules of order, or standing rules.

Last place: Custom

By custom, I mean procedures that aren’t written anywhere but are followed in actual practice just as if they’re written rules. Custom has its place, and any practice that’s taken on the standing of an unwritten rule is just as binding as if it were written, with one exception: If a written rule exists to the contrary, even in the parliamentary authority, the custom must yield as soon as the conflict is pointed out to the membership through a point of order; the only way around this exception is if a special rule of order is adopted to place the custom formally in the body of written rules.

So when Mr. Meticulous shows you the bylaw that requires all elections to be conducted by ballot vote, from then on, you have to have ballot votes, even if your organization’s custom has been to elect unopposed candidates by acclamation. In that case, you can no longer claim that custom has any standing.

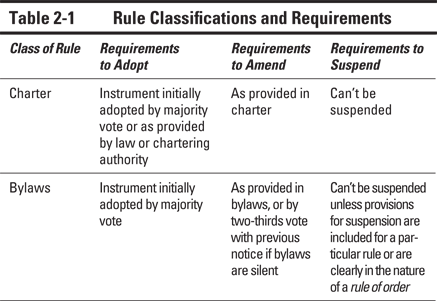

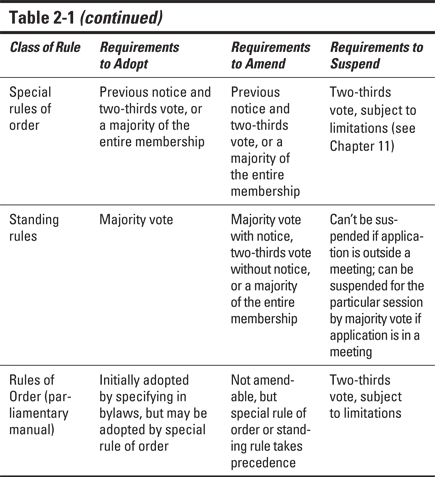

Laying down rule requirements

Fundamental differences exist in the procedures you use to adopt or amend each class of rules. Table 2-1 lists the rules by class and the requirements for their adoption, amendment, and suspension. (See Chapter 11 for rules on suspending rules.)

When you know the basics about the different classes of rules, it’s time to drill down to bylaws. Your bylaws are the heart of your organization’s structure.

Uncovering Bylaw Basics

Your bylaws comprise the fundamental rules that define your organization. They include all the rules that your group determines are of such importance that

They can’t be changed unless the members get previous notice of any proposed change, and a large majority (commonly two-thirds) is required to enact any proposed change.

They can’t be changed unless the members get previous notice of any proposed change, and a large majority (commonly two-thirds) is required to enact any proposed change.

They can’t be suspended (see Chapter 11), even by a unanimous vote.

They can’t be suspended (see Chapter 11), even by a unanimous vote.

Because bylaws are such a closely interrelated and customized set of rules, they’re gathered in a single document. With the exception of any laws governing your organization or your charter (if your organization is incorporated or is a unit of a larger organization), the bylaws take precedence over any and all other rules you adopt.

The nature of bylaws is sufficient to establish a contract between members and define their rights, duties, and mutual obligations. Bylaws contain substantive rules relating to the rights of members whether or not they’re present in meetings. The bylaws detail the extent to which the management of the organization’s business is handled by the membership, a subordinate board, or an executive committee.

You don’t have to go to all the trouble of taking your violation to the Supreme Court, however. You just have to take it to the membership by raising a point of order (see Chapter 11). Although the membership is considered supreme, it can’t even use a unanimous vote to make legal something that conflicts with the bylaws without amending the bylaws; to do so violates the rights of the absentees.

Breaking Down the Content of Bylaws

Your bylaws may have more articles than the basic list Robert’s Rules provides. (And that’s okay, unless you’re adding a lot of stuff that you shouldn’t.) In any case, the following list outlines the articles you need to have in your bylaws (and the order in which they need to appear) to cover the basic subjects common to most organizations.

1. Name: Specify the official name of your organization in this article.

2. Object: This article includes a succinct statement of the object or purpose for which your society is organized. This statement should be broad enough to cover anything your group may want to do as a group, but it should avoid enumerating details. When you list items, anything you leave out is deemed excluded.

3. Membership: Begin this article with details of the classes and types of membership, as well as the voting rights of each class. If a class of members doesn’t have full membership rights, be sure to specify which rights that class does have (to prevent headaches later). If you have eligibility requirements or special procedures for admission, include them under this article. Also include any requirements for dues, including due dates, rights or restrictions of delinquent members, explanations of when members are dropped from the rolls for nonpayment, and reinstatement rights. Any rules related to resignations and any intricate requirements related to memberships in subordinate or superior societies are included here, too.

4. Officers: This article is the place to explain specifications about the officers that your organization requires and any duties beyond those duties established by rule in your parliamentary authority (see Chapter 15). Sections including qualifications of officers; details of nomination, election, and terms of office (including restrictions on the number of consecutive terms (or total terms in a lifetime, if any); and rules for succession and vacancies are appropriately placed in this article. You may include a separate article to describe the duties of each officer.

5. Meetings: This article contains the dates for all regular meetings. Authority for special meetings, if they’re to be allowed, must appear in the bylaws. Details related to how and by whom special meetings can be called, and the notice required, are included here. Also, the quorum for meetings needs to be included in a section of this article.

6. Executive board: If your organization plans to have a board of directors to take care of business between your regular meetings (or all the time, if that’s the way you set it up), your bylaws must include an article establishing the board and providing all the details regarding the board’s authority and responsibility. Be clear and specific about who is on the board, how board members are elected or appointed, when the board is to meet, any special rules it must abide by, and, of course, specific details of the board’s powers.

The powers and duties of boards vary widely from one group to the next, and problems arise for many organizations whenever the members and the board have different ideas about the role and duties of the board. This article, therefore, must be developed or amended only with the greatest care.

The powers and duties of boards vary widely from one group to the next, and problems arise for many organizations whenever the members and the board have different ideas about the role and duties of the board. This article, therefore, must be developed or amended only with the greatest care.

It’s common not only to have an executive board to handle the business of the organization between membership meetings, but also to have an executive committee (that reports to the board) comprised of selected officers who are authorized to act for the board in the time between board meetings. The same amount of care must be taken when establishing the composition and power of an executive committee as when establishing a board. Furthermore, as with the executive board, no executive committee can exist except as the bylaws expressly provide for.

7. Committees: All regular standing committees that your group anticipates needing to carry out its business are defined under this article, each in its own section. The description of each standing committee needs to include the name of the committee, how its members are selected, and its role and function in the organization. If other standing committees may be needed, this article must contain an authorization for the formation of additional standing committees. Otherwise, the bylaws must be amended to create a standing committee.

8. Parliamentary authority: Adopting a parliamentary authority in your bylaws is the simplest and most efficient way to provide your group with binding rules of order under which to operate. The statement adopting the parliamentary authority needs to define clearly any rules to which the rules in your parliamentary authority must yield.

9. Amendment: The bylaws specify the precise requirements for previous notice and size of the vote required to change the bylaws. If your bylaws say nothing about amendment, and if Robert’s Rules is your parliamentary authority, then amending your bylaws requires previous notice and a two-thirds vote.

Making Sure the Bylaws Are Complete

If your bylaws include at least the basic articles I outline in the section “Breaking Down the Content of Bylaws,” you’re at least able to say that you have a set of bylaws. But a basic set of bylaws often isn’t enough. There are plenty of things you just can’t do unless you make provisions for them in your bylaws.

The actions in the following list are collected from throughout Robert’s Rules, but this list is by no means a complete one. It’s accurate, though, and it may help you if you’re wondering whether you can (or can’t) do something in your own organization.

If your bylaws don’t specifically authorize it, you can’t do the following:

Elect by plurality, cumulative, or preferential voting

Elect by plurality, cumulative, or preferential voting

Submit absentee votes (including votes by mail, fax, e-mail, or proxy)

Submit absentee votes (including votes by mail, fax, e-mail, or proxy)

Hold a runoff between the top two candidates

Hold a runoff between the top two candidates

Suspend a requirement for a ballot vote

Suspend a requirement for a ballot vote

Suspend a bylaw

Suspend a bylaw

Limit the right of the assembly to elect officers who aren’t members of your organization

Limit the right of the assembly to elect officers who aren’t members of your organization

Restrict the right of a member to cast a write-in vote

Restrict the right of a member to cast a write-in vote

Keep a vice president from assuming the office of the president if a vacancy occurs in the office of president

Keep a vice president from assuming the office of the president if a vacancy occurs in the office of president

Allow honorary officers or members to vote

Allow honorary officers or members to vote

Create an executive board

Create an executive board

Appoint an executive committee

Appoint an executive committee

Impose financial assessments on members

Impose financial assessments on members

Suspend a member’s voting rights or drop a member from the rolls for nonpayment of dues or assessments

Suspend a member’s voting rights or drop a member from the rolls for nonpayment of dues or assessments

Hold meetings by telephone conference, videoconference, or (heaven forbid) e-mail

Hold meetings by telephone conference, videoconference, or (heaven forbid) e-mail

Hold special meetings

Hold special meetings

Amending Your Bylaws

No matter how good a job you’ve done in creating your bylaws, sooner or later, you’ll need to change something. If you followed all the guidelines and instructions for creating proper bylaws, amending them won’t be so difficult that you can’t consider and make changes within a reasonable time when necessary — but they won’t be too easily amended.

Setting the conditions for amending your bylaws

Normally, amending something previously adopted (see Chapter 12) takes a majority vote if previous notice is given, a two-thirds vote without any previous notice, or a majority of the entire membership (see Chapter 8).

But amending a previously adopted bylaw is a different story. You want to ensure that the rights of all members continue to be protected. The surest way to provide this protection is to prevent bylaws from being changed without first giving every member an opportunity to weigh in on a change. And bylaws ought never be changed as long as a minority greater than one-third disagrees with the proposal.

Just think: If you can amend your bylaws by a majority vote at any meeting without notice, then Pete Sneak, Mabel Malevolent, and Connie Slink can assemble a small group on a slow night and, by excluding everyone not present from the right to vote, push through changes that allow the evil threesome to effectively take over all the group’s bank accounts.

This worst-case scenario illustrates why you make it a little more difficult to amend bylaws than to amend anything else. And you should always specify in your bylaws the exact requirements for their amendment.

Giving notice of bylaw amendments

Bylaws are important to orderly, productive organizations, so even if you don’t know many specifics about them, you can probably guess that bylaw amendments are pretty serious undertakings. Amending bylaws essentially changes the contract you’ve made with your fellow members about how your organization operates, so you need to be really technical and precise. The proper notice for a bylaw amendment contains three fundamental components:

The proposed amendment, precisely worded

The proposed amendment, precisely worded

The current bylaw

The current bylaw

The bylaw as it will read if the amendment is adopted

The bylaw as it will read if the amendment is adopted

Additionally, the notice commonly includes the proposers’ names and their rationale for offering the amendment. It may also include other information, such as whether a committee or board endorses or opposes the amendment.

I furnish a web link to an example form for a bylaw notice in Appendix B.

Handling a motion to amend bylaws

When the time comes to deal with the amendment on the floor, you’re handling a special application of the motion to Amend Something Previously Adopted (see Chapter 12). The bylaw amendment is subject to all the rules for that motion except for the following:

The provisions for amendment contained in your bylaws determine the requirements for previous notice and the vote required to adopt a bylaws amendment. But if your bylaws have no provisions for their amendment, the requirement is a two-thirds vote with previous notice or, without notice, a majority of the entire membership. Unless you say so in your bylaws (and you shouldn’t), amending bylaws by a majority vote or a majority of the entire membership is never in order.

The provisions for amendment contained in your bylaws determine the requirements for previous notice and the vote required to adopt a bylaws amendment. But if your bylaws have no provisions for their amendment, the requirement is a two-thirds vote with previous notice or, without notice, a majority of the entire membership. Unless you say so in your bylaws (and you shouldn’t), amending bylaws by a majority vote or a majority of the entire membership is never in order.

Primary and secondary amendments to your proposed bylaws amendment can’t exceed the scope of the notice. For example, if the proposed amendment was noticed as one to raise the dues by $10, then you can’t amend the proposal to increase the dues by more than $10. (Nor can you amend the proposal to lower the dues by any amount!) But you can amend the proposal to increase the dues only $8, because an $8 increase is within the scope of notice.

Primary and secondary amendments to your proposed bylaws amendment can’t exceed the scope of the notice. For example, if the proposed amendment was noticed as one to raise the dues by $10, then you can’t amend the proposal to increase the dues by more than $10. (Nor can you amend the proposal to lower the dues by any amount!) But you can amend the proposal to increase the dues only $8, because an $8 increase is within the scope of notice.

After you’ve adopted an amendment, that’s it — you can’t reconsider the vote. (But if the amendment fails, you can reconsider that vote.) See Chapter 12 for more information on the motion to Reconsider.

After you’ve adopted an amendment, that’s it — you can’t reconsider the vote. (But if the amendment fails, you can reconsider that vote.) See Chapter 12 for more information on the motion to Reconsider.

The rule against considering essentially the same question twice in a meeting doesn’t apply when you’re amending bylaws. Members may offer different approaches to accomplishing similar goals, and all bylaw amendments included in the notice are eligible for consideration.

The rule against considering essentially the same question twice in a meeting doesn’t apply when you’re amending bylaws. Members may offer different approaches to accomplishing similar goals, and all bylaw amendments included in the notice are eligible for consideration.

Amending specific articles, sections, or subsections of your bylaws

Proposed amendments to bylaws are main motions, which means that the amendments are themselves open to primary and secondary amendments.

When you’re amending parts of your bylaws, you propose the amendment as a main motion and specify one of the same processes used for any amendment. The processes of the motion to Amend, which are described in detail in Chapter 9, are as follows:

Strike out words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Strike out words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Insert (or add) words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Insert (or add) words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Strike out and insert (or substitute) words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Strike out and insert (or substitute) words, sentences, or paragraphs.

Any primary or secondary amendments to the proposed bylaws amendment must be within the scope of notice, as I describe it in the previous section. However, when your amendment is noticed as a substitution of an article or section, and some part of the substitution is no different from the original bylaw, then you’re prohibited from amending that particular part when considering the substitution. When no change is proposed, any change is considered outside the scope of the notice.

Tackling a full revision of your bylaws

A revision to bylaws is an extensive rewrite that often makes fundamental changes to the structure of the organization.

By considering a revision of your bylaws, you’re proposing to substitute a new set of bylaws for the existing ones. Therefore, the rules regarding scope of notice that limit primary and secondary amendments don’t apply. Your group is free to amend anything in the proposed revision before it’s adopted, as if it were considering and adopting the bylaws for the first time.

Recording the results of the vote

Bylaws amendments (requiring a two-thirds vote) are handled as a rising vote (see Chapter 8) unless the amendments are adopted by unanimous consent. However, because of the importance of bylaws and the impact of their amendment, unless the vote is practically unanimous, the best and fairest procedure is to count the vote and record the result in the minutes.

Interpreting Bylaws

Your bylaws belong to your group, and only your group can decide what they mean. A parliamentarian can help you understand the technical meaning of a phrase or a section, but when you come across something ambiguous (meaning that there’s more than one way to reasonably interpret something), the question needs to be answered by the members of your organization by a majority vote at a meeting.

Robert’s Rules lists some principles of interpretation to help you determine what’s truly ambiguous and what’s just a matter of following a rule for interpretation. I list and discuss these principles here in the context of bylaws, but the principles apply to other rules, too.

Bylaws are subject to interpretation only when ambiguity arises. If the meaning is clear, not even a unanimous vote can impute to them a different meaning. In other words, if you want a bylaw to have a different meaning, you have to amend it.

Bylaws are subject to interpretation only when ambiguity arises. If the meaning is clear, not even a unanimous vote can impute to them a different meaning. In other words, if you want a bylaw to have a different meaning, you have to amend it.

When bylaws are subject to interpretation, no interpretation can be made that creates a conflict with another bylaw. You’re also obligated to take into account the original intent of the bylaw, if it can be ascertained.

When bylaws are subject to interpretation, no interpretation can be made that creates a conflict with another bylaw. You’re also obligated to take into account the original intent of the bylaw, if it can be ascertained.

If a provision of the bylaws has two reasonable interpretations, but one interpretation makes another bylaw absurd or impossible to reconcile and the other interpretation doesn’t, you have to go with the one that doesn’t have a negative effect on existing bylaws.

If a provision of the bylaws has two reasonable interpretations, but one interpretation makes another bylaw absurd or impossible to reconcile and the other interpretation doesn’t, you have to go with the one that doesn’t have a negative effect on existing bylaws.

A more specific rule takes control when you have a conflict between the specific rule and a more general rule. For example, if your bylaws say that no relatives are permitted at meetings and another individual bylaw says that you can bring your spouse to the annual meeting and barn dance, be prepared to buy your spouse a new dress or a new tie before the festivities begin.

A more specific rule takes control when you have a conflict between the specific rule and a more general rule. For example, if your bylaws say that no relatives are permitted at meetings and another individual bylaw says that you can bring your spouse to the annual meeting and barn dance, be prepared to buy your spouse a new dress or a new tie before the festivities begin.

When bylaws authorize specific items in the same class, other items of the same class are not permitted. For example, if your bylaws allow members to enter cats, dogs, hamsters, and ferrets in the annual pet parade, then elephants are off-limits.

When bylaws authorize specific items in the same class, other items of the same class are not permitted. For example, if your bylaws allow members to enter cats, dogs, hamsters, and ferrets in the annual pet parade, then elephants are off-limits.

When a bylaw authorizes a specific privilege, no privilege greater than the one that’s authorized is permitted. For example, if your bylaws say that your board can provide refreshments for the members at meetings, that doesn’t mean the board can host a banquet at the Ritz.

When a bylaw authorizes a specific privilege, no privilege greater than the one that’s authorized is permitted. For example, if your bylaws say that your board can provide refreshments for the members at meetings, that doesn’t mean the board can host a banquet at the Ritz.

If a bylaw prohibits something, then everything beyond what’s prohibited (or limited) is also prohibited. However, other things not expressly prohibited or not as far-reaching as the prohibition are still permitted. For example, if your bylaws say that you can’t throw rotten fruit at your president during a meeting, then you probably can get away with catapulting a spoonful of fresh stewed tomatoes in his direction.

If a bylaw prohibits something, then everything beyond what’s prohibited (or limited) is also prohibited. However, other things not expressly prohibited or not as far-reaching as the prohibition are still permitted. For example, if your bylaws say that you can’t throw rotten fruit at your president during a meeting, then you probably can get away with catapulting a spoonful of fresh stewed tomatoes in his direction.

If a bylaw prescribes a specific penalty, the penalty can’t be increased or decreased except by amending the bylaws. For example, if you say that a member shall be expelled for speaking ill of the Grand Mazonka, then a member who calls the GM a louse must be expelled, but you can’t kick him on the backside as he heads for the exit.

If a bylaw prescribes a specific penalty, the penalty can’t be increased or decreased except by amending the bylaws. For example, if you say that a member shall be expelled for speaking ill of the Grand Mazonka, then a member who calls the GM a louse must be expelled, but you can’t kick him on the backside as he heads for the exit.

If a bylaw uses a general term and then establishes specific terms that are completely included in the general term, then a rule that’s applicable to the general term applies to all the specific terms. For example, if your bylaws define a class of membership as Royal Pains and that class includes Hot Shots and Know-It-Alls, then a rule applying to Royal Pains applies to both the Hot Shots and the Know-It-Alls as well.

If a bylaw uses a general term and then establishes specific terms that are completely included in the general term, then a rule that’s applicable to the general term applies to all the specific terms. For example, if your bylaws define a class of membership as Royal Pains and that class includes Hot Shots and Know-It-Alls, then a rule applying to Royal Pains applies to both the Hot Shots and the Know-It-Alls as well.

Publishing Your Bylaws and Other Rules

As I explain in Chapter 15, one of the duties of the secretary is to maintain a record book containing the current bylaws and rules of your group. This book needs to be available at meetings for easy reference.

Standing rules, which are, for the most part, policies related to the details of administration, are maintained as a current list. Update the list as rules are added, amended, or rescinded. Unlike the bylaws and special rules of order, the list of standing rules is normally furnished only to your officers and staff so that they can perform their duties in accordance with the policies the membership has adopted.

A country

A country