Chapter 10

Privileged Motions: Getting Through the Meeting

In This Chapter

Dealing with special needs immediately

Dealing with special needs immediately

Understanding the ranking of privileged motions

Understanding the ranking of privileged motions

Knowing when (and how) to use the right privileged motion

Knowing when (and how) to use the right privileged motion

Often meetings are interrupted by issues that are unrelated to the motion being discussed but that require immediate decisions. For example, your group may agree on a schedule for the business of the evening and then find that something is taking more than its allotted time and you want to get back on schedule. Or perhaps a problem develops that affects the comfort of the group. Or you may want to take a short break — or even quit, go home, and finish your discussions later.

When one of these situations arises, privileged motions help you take care of the problem and get on with your business.

The privileged motions (listed in order of rank, from lowest to highest) are as follows:

Call for Orders of the Day

Call for Orders of the Day

Raise a Question of Privilege

Raise a Question of Privilege

Recess

Recess

Adjourn

Adjourn

Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn

Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn

Table 10-1 shows the most common use for each privileged motion. I discuss the privileged motions in more detail throughout this chapter.

Table 10-1 Common Uses for Privileged Motions

|

If You Want To . . . |

Then Use . . . |

|

Get the meeting back on schedule |

Call for Orders of the Day |

|

Deal with something that affects the comfort of the group or even a single member |

Raise a Question of Privilege |

|

Take a short break |

Recess |

|

End the meeting |

Adjourn |

|

Continue the current meeting on another day |

Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn |

Ranking the Privileged Motions

Each privileged motion has a specific purpose, and each has a rank or specific order in which they can be used. Privileged motions outrank subsidiary motions, which I cover in Chapter 9.

The established ranking of privileged motions is logical. For example, it doesn’t make any sense to move to Recess (take a short break) when a privileged motion to Adjourn (end the meeting) is under consideration. Yet if the motion to Adjourn is on the floor, it’s possible that members may want to establish a continuation of the current meeting rather than just end everything until the next regular meeting.

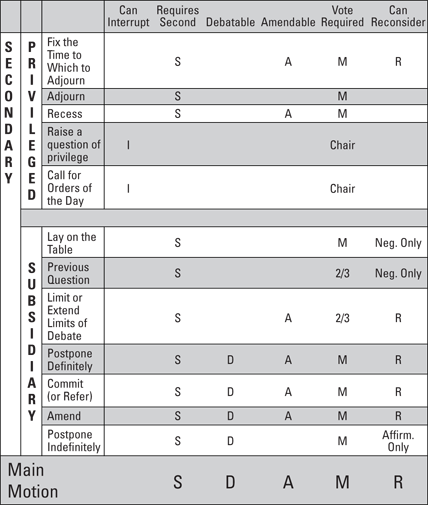

As Figure 10-1 depicts, when a motion is being considered, the motions below it on the list are out of order until the assembly has disposed of the one being considered. However, motions above the motion in question can be moved and considered no matter what’s pending in the lower ranks.

Note in Figure 10-1 that none of the privileged motions is debatable, and only two of these motions are amendable (because you have to decide times and dates). These motions are all about making an informed decision without wasting time.

Figure 10-1: Motion table showing privileged motions according to rank.

In the following sections, I discuss the five privileged motions and cover the function of each in more detail.

Getting Back on Schedule: Call for Orders of the Day

Your time is important. So is that of other members. Your meeting has a purpose and a goal of taking care of the group’s business within a specific time frame. Meeting time is the time to get down to business, make decisions, and go home.

Recognizing the value of your time, Robert’s Rules gives you a special motion to use to keep the meeting running on schedule. If you’re in a meeting and see that the group isn’t following the adopted agenda (or program, or order of business established by rule), or if the time has arrived for an item of business and the chair continues other pending business, you can insist that the schedule be followed.

In such a situation, the privileged motion to Call for Orders of the Day is just what you need. With this motion, the demand of a single member requires the group to resume the scheduled business immediately, unless the members decide otherwise by a two-thirds vote.

Using the motion to Call for Orders of the Day

Using a call for orders of the day is appropriate in two situations:

When the time arrives for a particular item of business to be discussed, but other business continues

When the time arrives for a particular item of business to be discussed, but other business continues

When, for some reason, the group isn’t addressing business in the proper order

When, for some reason, the group isn’t addressing business in the proper order

To make this privileged motion, simply rise and say, “Mr. Chairman, I call for the orders of the day.” You may also say, “Madam President, I demand that the regular order be immediately resumed.”

Your presiding officer is responsible for keeping the meeting on track, and when this motion is made, his duty is to proceed immediately to the proper item of business.

The chair responds to the member calling for orders of the day by saying, “Orders of the day are called for,” and proceeding to announce the proper current item of business.

Setting aside the orders of the day

If the presiding officer or one of the members thinks that the members would likely rather continue the business currently before them, he can proceed as follows:

Instead of proceeding immediately to the scheduled item of business, the chair can inform the assembly of the item of business that’s in order and ask whether the members want to move on to that item. The members can choose to continue with the currently pending business by a two-thirds vote in the negative.

Instead of proceeding immediately to the scheduled item of business, the chair can inform the assembly of the item of business that’s in order and ask whether the members want to move on to that item. The members can choose to continue with the currently pending business by a two-thirds vote in the negative.

A member can simply move that the time for consideration of the currently pending business be extended, or that the rules be suspended (see Chapter 11) and that the group take up a particular matter. Either way, the motion requires a two-thirds vote in the affirmative.

A member can simply move that the time for consideration of the currently pending business be extended, or that the rules be suspended (see Chapter 11) and that the group take up a particular matter. Either way, the motion requires a two-thirds vote in the affirmative.

Six key characteristics of the motion to Call for Orders of the Day

The motion to Call for Orders of the Day

Can interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Can interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Doesn’t need to be seconded

Doesn’t need to be seconded

Isn’t debatable

Isn’t debatable

Can’t be amended

Can’t be amended

Requires enforcement on the call of any member unless the members, by a two-thirds vote, decide to continue with the currently pending business

Requires enforcement on the call of any member unless the members, by a two-thirds vote, decide to continue with the currently pending business

Can’t be reconsidered

Can’t be reconsidered

It’s Cold in Here: Raise a Question of Privilege

Plenty of situations can arise during meetings that keep members from being comfortable or able to concentrate on the business at hand. A good illustration of such disturbances plays out in a scene from my high-school days.

My chemistry classroom was near the band practice field, and during football season, the band tuned up at the same time my class started. The cacophony was deafening, and no one could hear the teacher explain the importance of not letting the sodium get wet. It was too hot to close the window and muffle the noise. Thankfully, the leader of the majorettes (who was hot) was able to talk the bandmaster into ordering an about-face while the tune-up continued, and the noise was abated because all the horns were suddenly tooting in the opposite direction. The class was able to proceed in a relatively quiet and well-ventilated classroom.

Such is the nature of meetings. Air conditioners are set too low or too high, there’s noise out in the hall, or a group of members is abuzz about something and you can’t hear the discussion. Anything that affects the comfort of the assembly can be dealt with on the request of one member who raises a question of privilege.

More often than not, the motion to Raise a Question of Privilege is made to solve some immediate problem of particular and immediate annoyance to the group. But this motion covers other situations, too.

Here are the two types of questions of privilege:

Ones dealing with matters that affect the entire group. Examples include the physical comfort of members, questions about the organization, questions about the conduct of its officers or employees, and questions about the accuracy of published reports.

Ones dealing with matters that affect the entire group. Examples include the physical comfort of members, questions about the organization, questions about the conduct of its officers or employees, and questions about the accuracy of published reports.

Ones dealing with matters that affect an individual. An example of this type is an inaccurate report of something a member has said or done.

Ones dealing with matters that affect an individual. An example of this type is an inaccurate report of something a member has said or done.

Using the motion to Raise a Question of Privilege

There you sit, seventh row from the back in a small and crowded meeting hall. The meeting of the Association of Seersucker Beanbag Manufacturers is underway, and the group is debating an important motion. Some bonehead is out in the hall talking about his recent foot surgery, and you’re not only disgusted, but you’re also unable to concentrate on the debate.

What to do? Easy! Raise a question of privilege! Stand up and (interrupting the current speaker because you just don’t want to miss anything more of what’s being said) say, “Mr. Chairman, I rise to a question of privilege affecting the assembly. There is a loud disturbance coming from the hall, and a large number of us cannot hear or concentrate on the discussion.”

The chair may respond, “Will the bonehead in the hall please shut up and take his foot with him?” No, sorry — I’m just kidding. That’s probably what he’d like to say, but as I discuss in Chapter 7, the chair must avoid getting personal and stick to the issue at hand.

The chair really should say, “Will someone please ask the members in the hall to remove the conversation from the doorway, and please close the doors to the hall?”

Suppose you’re in a board meeting, and the executive director and two committee chairmen, none of whom is a board member, are present. The executive director has just finished her report, and serious problems with her job performance are apparent.

You want to make a motion to consider her continued employment at a change in salary, and you believe only the board members should be in the room when you make the motion. So you raise a question of privilege relating to the assembly so that the group can decide immediately whether to go into executive session and consider your motion.

The question of whether to go into executive session and take up your motion immediately is the question of privilege; the motion you make concerning the executive director is just a main motion whose immediate consideration is made possible by raising the question of privilege.

Six key characteristics of the motion to Raise a Question of Privilege

The motion to Raise a Question of Privilege

Can interrupt a speaker who has the floor, but only if the motion’s object would be lost by waiting. Otherwise, the motion can interrupt pending business, but the member offering it must first obtain recognition by the chair.

Can interrupt a speaker who has the floor, but only if the motion’s object would be lost by waiting. Otherwise, the motion can interrupt pending business, but the member offering it must first obtain recognition by the chair.

Doesn’t need to be seconded, but if the solution to the problem being addressed requires another motion, that motion needs to be seconded.

Doesn’t need to be seconded, but if the solution to the problem being addressed requires another motion, that motion needs to be seconded.

Isn’t debatable regarding whether to allow the question of privilege, but if the privilege, when granted, puts a main motion before the assembly, then that main motion is debatable.

Isn’t debatable regarding whether to allow the question of privilege, but if the privilege, when granted, puts a main motion before the assembly, then that main motion is debatable.

Can’t be amended regarding whether to allow the question of privilege, but if the privilege, when granted, puts a main motion before the assembly, then that main motion is amendable.

Can’t be amended regarding whether to allow the question of privilege, but if the privilege, when granted, puts a main motion before the assembly, then that main motion is amendable.

Is decided (ruled on) by the chair.

Is decided (ruled on) by the chair.

Can’t be reconsidered if it’s the chair’s decision (ruling).

Can’t be reconsidered if it’s the chair’s decision (ruling).

Taking a Break: Recess

No, it’s not time to go out to the playground and climb the jungle gym. Well, maybe it feels like time for that kind of recess, but it’s not likely to happen unless you’re in class and this book is your parliamentary procedure textbook. Recess, in this sense, usually refers only to taking a break in the middle of a meeting. But I promise you that the feeling is the same. Recess is recess!

Well, almost. Recess, like other privileged and subsidiary motions, also has a form for use as an incidental main motion (see Chapter 6) and has a few different rules if it’s made when nothing else is pending and the group wants to take a short break.

But the privileged motion to Recess is made to consider whether to take a short break immediately while another motion is pending. It can interrupt just about anything under consideration other than one of the privileged motions concerning adjournment.

Using the motion to Recess

I can’t remember any time in my career, either as a member or as a parliamentarian, when a motion to take a recess failed. About the only time it may not go through is when somebody trumps the motion with a motion to Adjourn.

The motion to Recess provides for a short break in the proceedings, and the privileged motion is one that’s used to get a recess immediately, even while you’re in the middle of something. It can be used strategically to allow an opportunity for a caucus, or simply so you can step outside for a breath of fresh air.

Because a motion to Recess can’t interrupt a speaker, you’re required to wait for recognition by the chair. But the form is simple: “Madam Chairman, I move that we take a 15-minute recess,” or “Mr. President, I move we take a recess until 3 p.m.,” or “I move we recess until reconvened by the chair.”

Unless your meeting is holding everyone rapt in enjoyment of the discussion, calls of “second” are likely to erupt from all corners of the room (and from the middle and sides, too!). Unless it appears that the motion to Recess may meet objection or perhaps an amendment to deal with the length of the recess, the chair can usually obtain general (or unanimous) consent (see Chapter 8). If objection arises or an amendment is offered, a voice vote is the way to go.

To resume business as usual, the chair calls the meeting back to order by saying something like, “The recess is ended, and the meeting will come to order.”

That’s it. You’re back — refreshed, reenergized, regrouped, and ready to proceed.

Six key characteristics of the motion to Recess

The motion to Recess, as a privileged motion,

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Must be seconded

Must be seconded

Isn’t debatable

Isn’t debatable

Is amendable with respect to the length of the recess, with no debate permitted on such an amendment

Is amendable with respect to the length of the recess, with no debate permitted on such an amendment

Must have a majority vote

Must have a majority vote

Can’t be reconsidered

Can’t be reconsidered

Time to Get Outta Here: Adjourn

Those magic words, “I declare the meeting adjourned!” Who doesn’t love ’em? Most of the time, nobody. In fact, as great as meetings can be when conducted by effective leaders who know what they’re doing, adjourning is probably bad news only when your great idea is on the floor and is close to being adopted, and the opposition uses the motion to Adjourn to successfully close the meeting.

Needless to say, I’m convinced it’s one of the world’s most favorite motions. You just can’t have a successful meeting without it!

Between the time the motion to Adjourn is adopted and the time the chair declares the meeting adjourned, any one or more of the following actions are permitted and in order:

Providing information about business that requires attention before adjournment

Providing information about business that requires attention before adjournment

Making important announcements

Making important announcements

Giving notice of a motion to reconsider a vote that took place at the meeting

Giving notice of a motion to reconsider a vote that took place at the meeting

Moving to Reconsider and Enter on the Minutes (see Chapter 12) in connection with a vote that took place at the meeting

Moving to Reconsider and Enter on the Minutes (see Chapter 12) in connection with a vote that took place at the meeting

Giving notice for any future motion that requires previous notice to be given at a meeting

Giving notice for any future motion that requires previous notice to be given at a meeting

Moving to set the time for an adjourned meeting

Moving to set the time for an adjourned meeting

In some situations, adjournment can take place without a motion. One is when the hour adopted for adjournment has arrived. At that time, the chair announces the fact, and unless you or someone else is pretty quick to move to set aside the orders of the day, the meeting may be adjourned by declaration.

Another instance in which adjournment doesn’t need a motion is when some emergency or immediate danger makes hanging around for a vote a really knuckle-brained thing to do. For example, if there’s a fire, your presiding officer should just break the glass to set off the alarm, and then declare the meeting adjourned to meet again at the call of the chair.

The other (more common) scenario in which adjournment can happen without a motion is when you’ve reached the end of the agenda. In that case, the chair may just ask whether there’s any more business; if you don’t speak up to make that motion you’ve been thinking about, and if no one else speaks up, the presiding officer can declare the meeting adjourned. Everybody can go out for coffee and beignets (I’m in Louisiana, and we love those little fried, square donuts!) before going home after the meeting.

Using the motion to Adjourn

The motion to Adjourn is straightforward and simple. It comes in three basic forms:

Adjourn now: “Madam President, I move to adjourn.”

Adjourn now: “Madam President, I move to adjourn.”

Adopting the motion closes the meeting. At the heart of everyone making this motion is the bleeding desire to fold it up and go home! This form of the motion is always privileged, meaning that even when nothing else is pending, the motion to Adjourn must be immediately disposed of by direct vote, unless the higher-ranking motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn is made. (I discuss that motion in the final section of this chapter.)

This form of Adjourn is the only way in which the motion may be used as a privileged motion (meaning that it can be made while other business is pending).

This form of Adjourn is the only way in which the motion may be used as a privileged motion (meaning that it can be made while other business is pending).

If you’re adjourning a meeting in a session with meetings still to be held, you pick up in the next meeting right where you left off when you adjourned (when you get past the usual meeting-opening rituals and any reading and approval of minutes). But if you adjourn and no meeting is going to occur until your next regular meeting, any motions not disposed of go forward as unfinished business.

If you’re adjourning a meeting in a session with meetings still to be held, you pick up in the next meeting right where you left off when you adjourned (when you get past the usual meeting-opening rituals and any reading and approval of minutes). But if you adjourn and no meeting is going to occur until your next regular meeting, any motions not disposed of go forward as unfinished business.

If your next regular meeting won’t be held within a quarterly time interval (see Appendix A for that definition), or if a change in membership will occur because of expirations of terms of members (such as may be the case in an executive board), all motions pending and not disposed of (or sent to a committee) fall to the ground. If they need to be acted on, you just have to pick them up, dust them off, and introduce them again at the next meeting.

If your next regular meeting won’t be held within a quarterly time interval (see Appendix A for that definition), or if a change in membership will occur because of expirations of terms of members (such as may be the case in an executive board), all motions pending and not disposed of (or sent to a committee) fall to the ground. If they need to be acted on, you just have to pick them up, dust them off, and introduce them again at the next meeting.

Adjourn to continue the meeting later: “Madam President, I move to Adjourn to meet again tomorrow at 8 a.m.”

Adjourn to continue the meeting later: “Madam President, I move to Adjourn to meet again tomorrow at 8 a.m.”

This form sets up a continuation of the current meeting. Tomorrow’s meeting is called an adjourned meeting or an adjournment of the current meeting. At the heart of everyone making this motion is the same bleeding desire to get away from it all until they’re dragged kicking and screaming back, being required by duty to continue an unfinished agenda.

Adjourn sine die (without day): “Mr. Chairman, I move to Adjourn sine die.”

Adjourn sine die (without day): “Mr. Chairman, I move to Adjourn sine die.”

This form adjourns the assembly completely and is used to end the final meeting of a convention of delegates.

Although the second two forms are not privileged (meaning that they’re in order only as main motions and can be made only when no other business is pending), the rules of procedure are otherwise the same.

Six key characteristics of the motion to Adjourn

The privileged motion to Adjourn

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Must be seconded

Must be seconded

Can’t be debated

Can’t be debated

Can’t be amended

Can’t be amended

Must have a majority vote

Must have a majority vote

Can’t be reconsidered, but can be renewed if any business has gone forward after a motion to Adjourn has failed

Can’t be reconsidered, but can be renewed if any business has gone forward after a motion to Adjourn has failed

Let’s Go Home and Finish on Another Day: Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn

The last of the privileged motions on the list, the motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn, is the one that can be made at just about any time, no matter what else is before your meeting.

It may become clear at some point in the meeting that you need more time if you’re to get everything accomplished that you intended. And you don’t want to wait until the next regular meeting to finish things up. You may be dealing with elections or just an overloaded agenda. You may not even have another regular meeting scheduled for a long time. When you find yourself in this situation, you want to provide for an adjourned meeting.

An adjourned meeting refers to a meeting that continues the same order of business, or agenda, that wasn’t concluded in an earlier meeting. It’s a separate meeting, in one sense, but it’s technically a continuation of the same meeting. The adjourned meeting mostly takes care of important business that shouldn’t (or mustn’t) wait until the next regular meeting, but that can’t go forward in the current meeting because of a lack of time (or perhaps a lack of a quorum). (Flip to Chapter 4 for a thorough discussion of quorum.)

Using the motion to Fix the Time to which to Adjourn

As soon as you realize that the work ahead of you is likely to consume more time than you have, the time is right to offer the motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn. It’s privileged when it’s made while other business is pending, and because it’s the highest-ranking motion, it takes precedence over just about everything, including a pending motion to Adjourn. That last little inclusion is great because it gives you or other judicious members of your organization one last chance to keep your good ideas alive and within reach of the membership before the next regular meeting. This consideration means a lot in the case of a group that meets only quarterly (or even less often).

This motion is introduced by saying, “Mr. Chairman, I move that, when we adjourn, we adjourn to meet again next Tuesday night at 6 p.m. at the clubhouse.” Or, if you need to keep some options open, say something like “. . . to meet next week on the call of the president.”

This motion is commonly used when a motion is made that would benefit from having an evening to itself. In this situation, the motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn is made as a way of postponing the motion until the assembly has enough time to handle it properly. You may even want to move to postpone the pending question to the adjourned meeting after adoption of the motion that sets the adjourned meeting. After adoption of the motion to postpone, the group can take up some other item of business in the current meeting before there’s a motion to Adjourn. Or if you’re running out of time, this privileged motion may be made to set up the time for an adjourned meeting just before making a motion to Adjourn.

Six key characteristics of the motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn

The privileged motion to Fix the Time to Which to Adjourn

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Can’t interrupt a speaker who has the floor

Must be seconded

Must be seconded

Can’t be debated

Can’t be debated

Can be amended only as to the date, hour, and place; such amendments cannot be debated

Can be amended only as to the date, hour, and place; such amendments cannot be debated

Needs a majority vote

Needs a majority vote

Can be reconsidered

Can be reconsidered