IN A FULL-PAGE AD in the June 13, 1999, Sunday New York Times, the National Funding Collaborative on Violence Prevention said this: “It should not have taken the Littleton tragedy to focus the nation’s attention and energies on preventing violence. . . . It should have been enough that children and adults in our society are victims of violence every day. . . . What is it about violence that we refuse to understand?” Indeed, what does it take to get us as a nation to see that there is a problem? Unfortunately, the increasing number of Littleton-like horror shows is what it takes. Does this make sense? And the problem with our reaction to the Littleton massacre is that we isolate the event; we separate out the actions of Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris from all the violence that is out there, and we in turn lose sight of what the National Funding Collaborative on Violence Prevention refers to as our “culture of violence.”

Let’s face it, we live in a violent world. We can see it in many aspects of our surroundings, and if we miss it we have a chance to see it played out again and again in the media. There have been countless books and studies on violence in our society and on how to prevent it and what it all means; there will, no doubt, be countless more. But this book is about how that violence, as it is dramatized on-screen in all its various forms, affects our children and conditions them to be more violent than they would naturally become without being exposed to it. Many have reduced this issue to a chicken-and-egg question: does violence on-screen make people violent, or is that violence merely mirroring what is actually taking place every day on our streets and around the world? We think the former, and we have the evidence to prove it. The point is that kids are not naturally violent; they are not born that way, despite what we may think. There are many factors in what makes anyone violent, but the overwhelming proof says that the entertainment industry, through violent programming and video games, is complicit in conditioning our youth to mirror the violence they see on-screen. Much like soldiers, children can and do become learned in this behavior, not by drill sergeants and trained military professionals, but by what they see around them. It seems logical to most of us but is still hotly contested by certain interest groups, and especially in the many levels of the entertainment industry.

But before we present the facts on the negative effects of screen violence on children—how and why it is making them violent—we need to first look at the overall trends of violence at home and abroad—our culture of violence. Essentially, around the world there has been an explosion of violent crime. Experts may disagree on what the statistics mean—many even suggest that all is getting better, not worse—but, in spite of vastly more effective lifesaving technology and techniques, as well as more sophisticated ways of battling crime, the rate at which citizens of the world are attempting to kill one another has increased at alarming rates over the years. According to InterPol, between 1977 and 1993 the per capita “serious assault” rate increased: nearly fivefold in Norway and Greece; approximately fourfold in Australia and New Zealand; it tripled in Sweden; and approximately doubled in Belgium, Denmark, England-Wales, France, Hungary, Netherlands, and Scotland. In Canada, per capita assaults increased almost fivefold between 1964 and 1993. And in Japan, in 1997, the juvenile violent crime rate increased 30 percent.

First and foremost, we must cut through the statistics, which are often easy to misread, and demonstrate just how violent we are and what kind of world our impressionable children are growing up in. Any discussion of the effects that screen violence has on our children must be seen through the lens of our society at large. Also, in order to tackle the seemingly insurmountable problem of violence in our world, we must first see what’s actually going on. If we can’t be convinced that the rate of violence is increasing, we are not, obviously, going to make a priority of tackling the issue. No problem means no need for a solution.

According to FBI reports, crime is down 7 percent. We are experiencing a slight downturn in murders and aggravated assaults, bringing us back to the crime rates of about 1990. But that is far from the full story. To gain a useful perspective on violent crime—among both youths and adults—the view must cover a long enough time period to clearly identify a trend. Up or down variations over a year or two are meaningless. Until a real trend over a span of years is identified, taking corrective action is difficult and understanding the main reasons for the trend is just about impossible. So what’s the big picture of crime in America?

From 1960 through 1991 the U.S. population increased by 40 percent, yet violent crime increased by 500 percent; murders increased by 170 percent, rapes 520 percent, and aggravated assaults 600 percent. In 1996 there were 19,645 murders, 95,769 reported rapes, over 1 million cases of aggravated assault, and 537,050 robberies, amounting to a loss of about $500 million in stolen property.

When applying statistics to the increasing tide of violence, it is important to distinguish between attempts to kill and injure and success at killing. The per capita homicide rate is a measure of how successful we are at killing each other. Murder is the least committed violent crime, although the most often reported crime on the nightly news. Only in the most unusual or extreme circumstances does a case of aggravated assault make the evening news. Yet the rate of aggravated assault clearly demonstrates increasing levels of violence.

We should also note that violent crime statistics are general indicators of the level of violence in society, but not a true measure of the level of violence. The real level of violence will always exceed the level indicated by the crime rates because crimes are not always reported. The level of reporting depends on the type of crime. Virtually all homicides are reported, mainly because as a society we do not allow dead bodies to lie around without investigation. Most robberies of any significant size are reported because someone has lost something of value—and they want to collect on the insurance. But crimes like rape, domestic violence, gang warfare, incidents related to the underworld, and some more minor aggravated assaults (where reporting the incident seems like more of a hassle than it’s worth) are underreported. Therefore, we must always take crime statistics with a grain of salt and realize they tell only so much of the story.

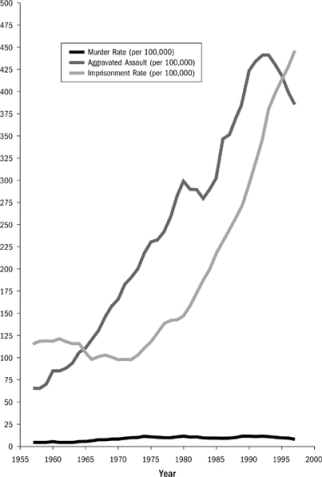

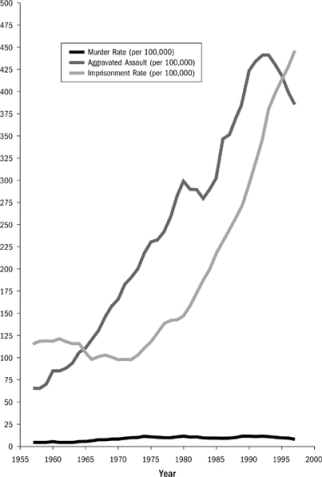

However, the crime statistics are really all we have to work with. For the objective side of the story we need these numbers to indicate the changing levels of violence, and these have to be numbers that show changes over reasonably long periods of time. The only available numbers over such periods of time are the above-cited crime statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports. Figure 1 demonstrates just how bad things have become.

If any one thing sticks out on this graph it is the disparity between the level of murders and that of aggravated assaults. Why, you ask, are they not increasing at the same rate? Considering he advances of our society in the last half-century—major medical discoveries, progressive social initiatives reducing malnutrition and confronting child abuse, a reduction in racial tensions, a booming economy, a sharp reduction in illegal drug use, a quadrupling of the incarceration rate, and advances in law enforcement technology, to name a few, coupled with an aging population—we should have seen a very precipitous decrease in murders and violent crime.

FIGURE 1. Violent Crime in America: A Comparison of the Murder, Assault, and Imprisonment Rates, 1957–1997. (Source data: “Statistical Abstract of the United States.” Washington, D.C.: The U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, editions 1957 to 1997.)

Let’s isolate the progress the medical community has made in saving lives. UCLA professor James Q. Wilson is among many experts who have determined that vast progress in medical technology since 1957 (including everything from mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to the national 911 emergency telephone system to advances in medical technology) has helped us save more lives. Otherwise, murder would be going up at about the same rate as attempted murder. Professor Wilson estimated over a decade ago that “if the quality of medical care (especially trauma and emergency care) were the same as it was in 1957, today’s murder rate would be three times higher.”

This view is corroborated by U.S. Army assessments of wound survivability. According to the U.S. Army Medical Service Corps, a hypothetical wound that nine out of ten times would have killed a soldier in World War II, would have been survived nine out of ten times by U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. This is due to the great leaps in battlefield evacuation and medical care technology between 1940 and 1970. And we have made even greater progress since 1970.

Consider, for instance, some of the advances in medical technology as they relate to treating wounds. Only a century ago, any puncture wound to the abdomen, skull, or lungs created a high probability of death. So did any significant loss of blood (there were no transfusions), most large wounds (no antibiotics or antiseptics), and most wounds requiring significant surgery (no anesthetics, resulting in death from surgery shock).

So, with the medical advances of the last fifty years—not to mention how much better we have become at transporting patients, communicating their conditions, and the speed with which we get them “on the table”—it simply makes sense that the homicide rate would be lower than the aggravated assault rate. We have managed to lessen the rate at which violence is successful in killing people. However, for the past forty years we have not only failed to lessen the rate at which we attempt to kill each other; we have precipitously increased it.

We now know the basic factors that help violence proliferate: poverty, institutional racism, child abuse, and drug abuse. And we are making inroads to understand these problems and do something about them. Of course, it will, in all likelihood, always be argued that we’re not doing enough. But think back a few decades. The world was a very different place, some say colder, where child abuse, drug abuse, and racism were for the most part not confronted or dealt with on any significant level. This is not the place to go into how we have come to address the above problems. But societal and technological initiatives abound that are addressing these social factors and that did not exist forty, thirty, or even ten years ago. Shouldn’t the advances that have followed these initiatives be contributing to an overall decrease in violence levels? One would think so.

Another way to reduce violent crime is to lock up violent criminals, something that we have been doing at an unprecedented rate. The per capita incarceration rate in America more than quadrupled between 1970, when it was at 97 people per 100,000, and 1997, when it reached 440 per 100,000. According to criminologist John J. DiIulio, “dozens of credible empirical analyses . . . leave no doubt that the increased use of prisons averted millions of serious crimes.” Some of those incarcerated are nonviolent criminals, but a consistent proportion of them are violent and there can be no doubt that, if not for our tremendous imprisonment rate (the highest of any industrialized nation in the world), the aggravated assault rate and the murder rate would be even higher.

The progress that has been made in law enforcement technology should also be working to keep down violent crime. Excluding well-planned robberies and murders, basic criminal violent behavior has changed little over the last several decades, but the police technology available to apprehend and convict the violent offender has made steady, significant progress. Portable two-way radios, computerized fingerprint systems and ID checks, DNA matching, video monitoring, and many other technological innovations have increased the odds of detection, capture, and conviction, and to that extent should be acting as a deterrent to crime.

Many effective results have also been achieved through ever more innovative and aggressive new police strategies. In Richmond, Virginia, a program of “zero tolerance” for violating federal gun laws (if you are a felon caught carrying a gun you get five years in prison, no exceptions) has been credited with cutting murders by 65 percent. In Boston, Massachusetts, a comprehensive program of nightly home visits by police and probation officers, a zero-tolerance policy for crime and gang activity, and severe punishment for providing guns to gangs and youth led to an 80 percent drop in youth homicides from 1990 to 1995, and in 1996 not a single youth died in a firearm homicide.

We should also see the positive effects of an aging population. The prime years for violent crime are roughly the years from ages sixteen to twenty-four. As the Baby Boomers have aged out of the “prime crime” years the numbers of citizens in their teens and twenties out on the streets has gone down significantly. It might appear that this would help bring down the rate of violent crimes. Yet, throughout this era of an aging population, the violent crime rate still went up.

So the point is made: crime in this country is increasing at an alarming rate and, ironically, most factors suggest it should be doing the opposite. Why, and, most important, where do our children fit into all this?

There are species within ecological systems that are more sensitive than others to environmental stressors. When biologists and ecologists study ecological systems they look at these key species—called indicator species—to understand how severely stressed the systems are. Are our children, socially marginalized and psychologically weakened, the indicator group for the level of violence in our society? Are they the canaries in our coal mines? Unfortunately, the answer is yes. Let’s consider some of the statistics regarding youth violence.

Among young people fifteen to twenty-four years old, murder is the second-leading cause of death. For African-American youths murder is number one.

Every five minutes a child is arrested in America for committing a violent crime, and gun-related violence takes the life of an American child every three hours.

A law enforcement survey estimates that there are at least 4,881 gangs in the United States, with about 250,000 members total.

A child growing up in Washington, D.C., or Chicago is fifteen times more likely to be murdered than a child in Northern Ireland.

Since 1960 teen suicide has tripled.

Every day an estimated 270,000 students bring guns to school.

One of every fifty children has a parent in prison.

Much of this violence is hidden. It doesn’t make headlines. Yet many of our children must live with it day in and day out. Consider these facts:

Bullying: At least 160,000 children miss school every day because they fear an attack or intimidation by other students.

Sexual Abuse: One out of three girls and one out of seven boys are sexually abused by the time they reach the age of eighteen.

Animal Mutilation: Teachers report more and more students as young as seven years old discussing the “thrills” of stabbing a kitten to death or torturing a pet.

As you can see from Figures 2 and 3, youth crime rates, for boys and girls, rose steadily from 1965 to 1985, then took a rather disturbing jump following that. And we hardly need graphs to see it. Children have always been somewhat prone to aggressive behavior, but psychologists are seeing it acted out in increasingly more menacing and deadly ways. In addition, children are becoming more desensitized and complacent toward their own violent acts and those of others. Words and phrases like “rampage,” “lockdown,” and “body count” have entered into their common language, said in a way that seems harmless enough until you realize what these things really mean. Stephen M. Case, of America Online, says that 80 percent of teenagers on AOL believe that what happened at Columbine could happen in their school. As mentioned above, we obsess on the actions of the kids who take it to the extreme, most likely forgetting that this is just the tip of the iceberg. Dr. Diane Levin, a professor at Whee-lock College in Boston, sums it up: “Not only are (our) children hurting each other in ways that young children never did before, but they are learning every day that violence is the preferred method of settling disputes.”

FIGURE 2. Violent Crime Arrest Rate for Juvenile Males (per 100,000). (Source data: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States 1996, Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice, 1996.)

FIGURE 3. Violent Crime Arrest Rate for Juvenile Females (per 100,000). (Source data: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States 1996, Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice, 1996.)

Think of how benign the term “juvenile delinquent” sounds these days. Kids in the 1950s who were described as such probably got up to some shoplifting, truancy, a fight or two. If they belonged to a gang they might have gotten into a rumble, maybe even a knife fight. But let’s face it, you didn’t hear about mass killings and terrorist-type behavior when it came to kids. (And it wasn’t simply because such things were not reported by the media.) Littleton would have been unfathomable to parents in the 1950s or 1960s, as would metal detectors in schools.

There is something quite disturbing about the kind of violence we are seeing in the schoolyards these days—it’s intense. There’s a rage out there that wasn’t there a few decades ago, and children are settling their differences in scary ways. We weren’t shocked to hear that at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, there are preps, jocks, nerds, outsiders—groups of different kids, some popular, some not; some well adjusted, some less so. It’s always been that way. Not so great for the kids on the outside, the ones who get picked on and bullied; but they didn’t tend to respond to that treatment by killing their classmates and teachers, as Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold did. What has changed enough to cause this? Of course, the world has changed much in the last half-century, but it’s hard to identify those factors that would lead to such behavior. Some blame it on increased access to guns. Such access is never a good thing, but we’re missing the point if we blame guns; the availability of guns has been a constant factor in the violence equation in the United States. The question we should be asking is why kids want to pick up weapons in the first place. Others blame the decay of societal values. Again, not a good thing for any of us but hardly enough of a reason to explain why children are killing in cold blood. If you run down all the possible factors, the myriad explanations, you will come to rest at one thing: the TV, movies, media, and video games that our kids are spending inordinate amounts of their time with. If you ask what’s really changed, that’s it—and we all know it. Over the last forty years, slowly, gradually, we have increased the levels of graphic violent imagery on our TVs, in our movies, and at our video arcades. And we have done so under the veil of acceptability. We have put younger and younger children in front of screens depicting horrific violence, and we have done little to address the effects it has had and will continue to have on them. We have no problem letting our children go out and see—or stay at home and watch—“slasher” films, a genre of movie that is aimed at the youth market. We have gone from the benign Pong video game in the 1970s to games in the 1990s that act more as murder simulators and permit youth to mimic the actual experience of killing. And all of this time we have become very good at avoiding the fact that this type of simulated violence has everything to do with the increasing level of violence we have clearly demonstrated in this chapter. Why are we alarmed to find out that the killers in Paducah, Jonesboro, and Littleton were weaned on violent entertainment? And why do we so readily accept the idea that this steady diet of blood and gore had little or even nothing to do with their actions? What do we expect? It’s time to hear the evidence.