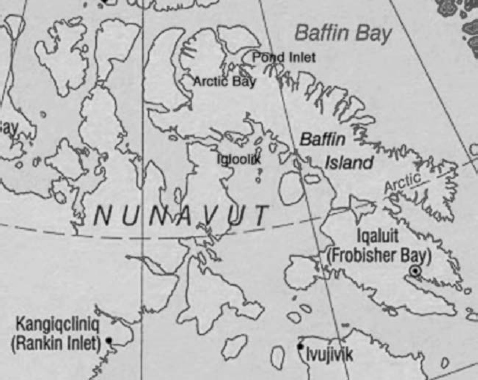

This article discusses the traditional musical style that dominates the Inuit from the Arctic East to West: the drum-dance song, or pisiq (plural pisiit).1 The syllabic a-ya-ya, which appears in the text of drum-dance songs from Alaska to Greenland, is used today to designate the whole of the song as well. The 315 drum-dance songs that provide the basis for this study are from the Iglulik Inuit area of northern Baffin Island. The songs were collected from the following hamlets: Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) (collected by Jean-Jacques Nattiez in 1976 and 1977), Igloolik (Nattiez in 1977), and Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay) (Lorne Smith in 1964 and Paula Conlon in 1985) (see Figure 1.1).2

The Iglulik Inuit of the present day are descended from the people who brought the Thule culture into the Baffin Island area around AD 1200. In 1822 Captains William Edward Parry and George Francis Lyon of the Royal Navy spent the winter at Igloolik during their search for the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans. When ethnologists Knud Rasmussen, Peter Freuchen, and Therkel Matthiassen arrived in Igloolik in 1921, they found the way of life still very much as it had been one hundred years before. Hunting was the chief activity, with char fishing as a supplementary activity performed by women (NWT 1990–91: 168).

The period 1920–60 has been referred to as the era of the “big three”: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the missions (Mary-Rousselière 1984: 443). In the 1960s, the Canadian government began systematically regrouping the Inuit around these installations. Modern aluminum houses were built in the hamlets of Admiralty Inlet, Sanirajak (Hall Beach), Igloolik, Ikpiarjuk, and Mittimatalik, and the government set up federal schools in Igloolik (1959), Mittimatalik (1960), and Ikpiarjuk (1962), with compulsory education for all children ages six to sixteen. The Inuit move freely among these communities, but the nomadic way of life, based on hunting and fishing, disappeared in fewer than ten years.

Figure 1.1. Map of Baffin Island. Courtesy of Tara Browner. Map template taken from public domain collection of the Perry-Castaneda Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

As the fieldwork for this study was carried out after the government’s regrouping of the Inuit in the 1960s, these songs were all collected “artificially.” The singers were asked to sing for the sole purpose of being recorded, with the result that the musical style of the recordings was sometimes affected by contact with white musical civilization and modern conditions of performance. In this sense, the collection represents the musical state of the Iglulik Inuit between 1964 and 1985 (Conlon 1992).3

Traditionally, a man composed a drum-dance song in solitude, usually while hunting. Once he had decided on the text and the melody, he repeated the song over and over so as not to forget it. When the hunter returned home, he taught the song to his wife, who in turn taught it to the other women in the village, to be ready for a public performance at the feasts (qarginiq). The women’s role is paramount because “the woman is supposed to be the man’s memory” (Rasmussen 1929: 240). When the composer was a visitor, he taught his song to the women of the host camp before the drum dance (Uyarak 1977).

There is no report, either from ethnographic sources or from consultants, of women dancing with the drum in the Iglulik area.4 Rasmussen notes that every man and woman, and some of the children, may have their own songs (with appropriate melodies) that can be sung in the qaggi (dance house) (1929: 227), but there is no information about how the women’s songs are presented. Of the 147 drum-dance songs (of known authorship) from Igloolik, Ikpiarjuk, and Mittimatalik, only 4 are attributed to female composers.

Although the character of Iglulik Inuit drum-dance songs is personal, this is not in the sense of property such as that exhibited by some North American Indian cultures. For instance, it is not necessary to ask permission before singing someone else’s song (Nattiez 1988: 45). An indication of the lack of possessiveness of songs is the availability of portions of common text in personal songs by different composers. During my fieldwork in Ikpiarjuk in 1985, many of the singers spoke about the communal aspect of the singing of another’s songs, saying that public acknowledgment of the original creator of the song was sufficient. Interviews from Nattiez’s fieldwork in 1976 and 1977 indicate a similar attitude toward song ownership at Mittimatalik and Igloolik.

The text in drum-dance songs is in large part linked to basic experiences in the Inuit way of life. Topics of songs include hunting, people, death, qallunaaq (white man), singing, and religion. As hunting is essential for survival and is the primary activity during which songs are created, it is not surprising to find that the theme of 68.5 percent of the song texts revolves around some aspect of hunting, as in this song: “The polar bear over there, I see it over there, ayaya … My harpoon, I suddenly want it now, ayaya. … My dogs there, I suddenly want them now, ayaya …” (Panipakoochoo 1977: 5d-84.PI77-10).5

The qallunaaq category (4 percent of songs) includes eight versions of a song dealing with “this little hook,” a feature of the syllabic alphabet used by missionaries in biblical translations (NWT 1990–91: 196). Whalers brought examples of these syllabic-print Bibles to Mittimatalik before the arrival of the missionaries in 1922 (Qango 1977), but the Inuit had no instruction in the use of the alphabet. The text is: “This little hook shape, I wish I could find out what it is, ayaya, I-E-OO-A-pie-pee-poo-pa, ayaya” (L. Kalluk 1985: 4g-3.AB85-30).

Songs listed under “singing” (4 percent of songs) deal with the process of composition and the frustration of attempting to create something new: “It turns out nothing was left for me, no future songs at all, ayaya. … Somebody said they were all gone. Our ancestors used up all the songs, ayaya …” (Ikaliiyuk 1977: 5e-15.IGL77-88).

The Inuit drum (qilaut) averages approximately seven inches in diameter but is known to vary in diameter from five to thirty-four inches.6 Drums from the eastern Arctic are typically larger than those found farther west. Figure 1.2 is a drum made by Aglak Atitat of Ikpiarjuk in 1985. Its diameter is twenty-three and a quarter inches.

To construct a drum, a wooden frame is bent by means of steaming and soaking.7 The frame is then tapered and nailed together in a circle, and the skin is bound tightly to the frame with sinew or string. The same cord that binds the drumhead also ties the drum handle. Like the drum handle, the mallet is roughly shaped to fit the hand. The mallet is then covered with sealskin.

Traditional drum dances were part of song festivals that usually took place in a large igloo called a qaggi, which could hold up to one hundred people. In order to announce a drum dance, someone would go out and shout for everybody to come over: “It was just like a community hall” (Uyarak 1977). In the qaggi, drum-dance competitions took place that generally involved the whole community. These festivals occurred when there was abundant food and generally started with a communal feast of caribou and seal. Festivals took place principally in autumn or winter, and sometimes took place between teams from different camps. Isapee Qango (from Igloolik) said that the length of the feast was usually around three days but could last up to five days (1977). Rasmussen notes that when there were visitors, the entertainment might go on all night, throughout the dark hours, which could be up to all twenty-four (1929: 228, 230).

Figure 1.2. Iglulik Inuit drum (maker: Aglak Atitat; collector: Paula Conlon; acquisition date: 1985).

No matter what form the competition took, there was clearly a winner. Along with the prestige gained, tangible prizes (such as harpoons) were sometimes awarded. The success of the song festival depended on the daily practicing of the songs by each family (Rasmussen 1929: 228). A more contemporary indication of this practice is that by François Quassa of Igloolik: “His mother-in-law used to sing a lot. … They used to live in one igloo, the whole family, in-laws, and everything. And she used to sing every night, before they went to sleep” (1977).

At the beginning of the festival, the drum (qilaut) was placed on the ground in the center of the qaggi. Any composer could start. When he took the drum, his wife began to sing his song. His wife was the leader (ingirtuq) of the choir (ingiortut) of women who had learned the song. The composer did not sing, although he cried out from time to time (Urrunaluk 1977).8 According to Rasmussen, “The mumirtuq (the dancer) will … often content himself with flinging out a few lines of the text, while his wife leads the chorus” (1929: 240). The term mumerneq, which means “changing about,” signifies the combination of the melody, the words, and the dance (Rasmussen 1929: 228).

While drum dancing, the man dances slightly bent over, holding the drum with his left hand (a left-handed man holds the drum in the right hand). With his wrist he pivots the drum from right to left. He uses the mallet (katutarq), covered with sealskin, to hit the wooden frame, alternately on the base (akkirtarpuq) and the top (anaulirpuq) of the drum. The feet are often synchronized with the beat of the drum to avoid fatigue (Urrunaluk 1977). Some drummers are so skillful in the handling of the drum that they can make it pivot in the air from side to side without holding the handle (Iyetuk 1977; Kupak 1977).

When the first dancer at a drum dance was finished, another took his place. The elder men present evaluated the merits of each song and dance. Although the competitive character of the traditional drum dance could take various forms, it was mainly a test of endurance to determine the capacity of the dancer to “hold the beat.” The longer the song, the heavier the drum seemed to become, and the large size of the drums from the eastern Arctic contributed to the difficulty. The number of songs known was also taken into consideration. In the hamlet of Igloolik, the song was said to wrap itself inside the wooden frame of the drum (Iyetuk 1977; Urrunaluk 1977), and the drum itself was considered responsible for the hardship of performing (Ikaliiyuk 1977).

The competition could involve all the men participating at a festival, but often it was specifically between illuqiik (singular illuq), that is, “song cousins.” This strong friendship was formed by mutual consent, signified by an exchange of wives, pleasantries, and food. At the feasts, song cousins took turns confronting each other with insult songs (iviut). But as Rasmussen points out, “Song cousins may very well expose each other in their respective songs, and thus deliver home truths, but it must always be done in a humorous form, and in words so chosen as to excite no feeling among the audience but that of merriment” (1929: 23).

Drum-dance competitions were also used to resolve serious disputes and involved vicious songs of derision. Rasmussen describes the song duel: “Here, no mercy must be shown; it is indeed considered manly to expose another’s weakness with the utmost sharpness and severity; but behind all such castigation there must be a touch of humour, for mere abuse in itself is barren, and cannot bring about any reconciliation” (1929: 231).

Social humiliation was the principal means of defeating one’s opponent, although these tournaments could be accompanied by physical confrontation as well (for example, boxing). Once the song duel was finished, the social equilibrium was restored. The quarrel became a thing of the past, and presents were exchanged to show that friendship had been reestablished (Rasmussen 1929: 232).

The song duel had a judicial character to resolve disputes peacefully, involving the entire community as the “jury,” but the drum dance also provided a social diversion, especially welcome during the long, dark winter months. Therefore, the drum dance and the drum-dance songs had a multifunctional dimension. They served to draw the people together and eased tensions arising from daily living in a close-knit community.

The drum-dance songs of this study were only rarely performed in the field situation with a drum (only 41 of 315 songs collected between 1964 and 1985). I was told that drum dances used to be held in the community center at Ikpiarjuk, but they faded in the early 1970s when the hall was closed. The songs with percussion collected from Igloolik and Mittimatalik in 1976 and 1977 were not part of a traditional drum dance, and during my fieldwork at Ikpiarjuk in 1985, I was able to arrange only a “staged” drum dance with two dancers, Aglak Atitat and David Kalluk.

David Kalluk (1985) told me that he and singer Koonoo Ipirq used to “go out to sing” at competitions such as those held at “Toonik Tyme” in nearby Iqaluit (Frobisher Bay). When I contacted government officials in Iqaluit to obtain permission to attend the festival, they warned me that I was not likely to find much traditional music. This proved to be the case, and when I attended Toonik Tyme in Iqaluit in the spring of 1987, the only drum dancing at the festival consisted of showpieces to open the festivities, performed by Lens Lyberth from East Greenland and Celestin Erkikjuk from Kangiqcliniq (Rankin Inlet).

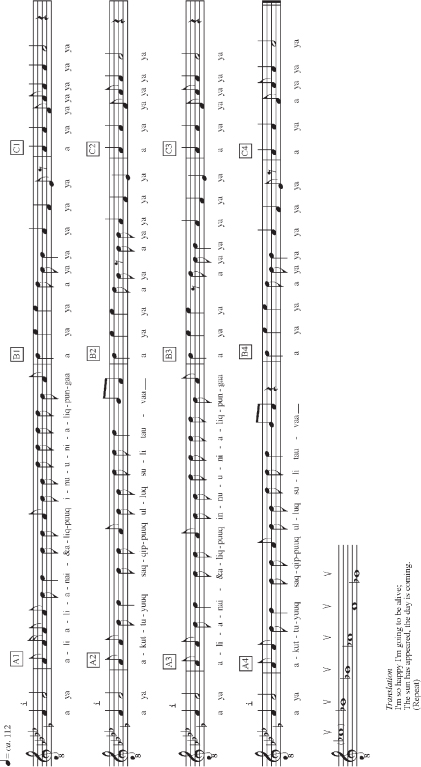

I have chosen to discuss the song “I’m So Happy” (5b-2.AB85-4) because of its illustration of the common features of drum-dance songs from the Iglulik area (see musical example 1.1). The title is derived from the first line of the text, a common method of referring to traditional drum-dance songs.

Eleven versions of the song “I’m So Happy” were collected from Mittimatalik (1976) and Ikpiarjuk (1985). The omission of this song from the Igloolik corpus suggests that it was known only locally. This song is ascribed to the singer Qargiuq: “One winter, he [Qargiuq] was really sick, with TB, and he thought he was going to die before spring. But he got better again, and when he was hunting seal, in springtime, he sang: ‘I’m so glad I’m going to live, to see the spring come again’” (Qango 1977).

The texts show the variations between versions while still retaining the overall meaning. The recurring figure of speech is the appearance of the sunrise, an appropriate moment for the Inuit when the spring arrives after months of darkness. The oxygen mask that appears in versions numbered 5b-9 and 5b-13 (and obliquely in 5b-3: “Let me breathe because I’ll be living”) refers to the personal experience of the composer, Qargiuq, and his association of his recovery from tuberculosis with spring.

Variations in text show how the story is retained in a number of guises, confirming this set of songs as being concordant. The establishment of an urtext is essential in determining concordances because its different versions can also use a variety of melodies. It is important to keep in mind the Inuit concept of drum-dance songs, as noted by Caribou Inuit Donald Suluk from Arviat (Eskimo Point): “In the Inuit way of listening to songs, you don’t really listen to the tune but to what is being said. … The song has to be sung completely and followed according to how it’s composed. But if it was to be sung, say, with some words missing or with the verses mixed up, it could insult the song’s writer or family members” (1983: 28). This emphasis on the story line was indicated again and again to me during my fieldwork when my consultants and interpreters would focus on the text. They would never say, “That is a nice tune.”

As a tone language, Inuktitut, through the text used, influences the melodic contours and pitches used in the songs. This accounts for the number of tone reiterations (unisons) that occur sporadically within a melody. Maija M. Lutz comments on the repetition on the same pitch in certain sections of Inuit songs from Cumberland Peninsula on southern Baffin Island (1978: 57), and this tendency is also noted among the Netsilik Inuit west of Hudson Bay (Cavanagh 1982: 122). Beverley Cavanagh maintains that rests exist only when a singer needs to take a breath and that the ideal performance would eliminate most breath divisions, creating a continuous melodic line (1982: 95). “The songs are logogenic, or closely derived from speech patterns. … Additional syllables are never accommodated by subdividing a beat, but rather by adding another. The words … would seem to be the most feasible and the most objective means of identifying ‘motives’ and examining the structural patterns formed by their combinations. … Most, though not all, words are similarly placed when a musical ‘motive’ reoccurs” (96–97, 133).

Musical example 1.1. Transcription of Iglulik Inuit drum-dance song “I’m So Happy.” Song 5b-2.AB85-4. Transcribed by Paula Conlon.

For the song “I’m So Happy,” I have chosen to divide the melody into three motives based primarily on the word structure. The first part of the melody (motive A on the first line) is sung to translatable text, whereas the second and third motives (motives B and C on the second line) make use of the ayaya vocable (syllables without translatable text that nevertheless have “meaning”). The third motive (C) serves to reiterate the tonal center with repeated repetitions on one pitch with the exception of a dip down the interval of a third and back up again at the beginning of the C section. Before each of the A motives is what I have termed an incipit (i): portions of the ayaya vocable that serve to situate the tonal center. As with the textual analysis, it is important to keep in mind that the melody is subservient to the text; the primary function of the singing is to tell the story and provide a vehicle for the drum dancing.

In the version of the song “I’m So Happy” numbered 5b-14 (recorded in 1976), the singer sings with a metronome marking of the quarter note at a rate of 92 beats per minute, whereas the drummer is performing with a drumbeat at a rate of 100 beats per minute, indicating a significant discrepancy between the tempo of the voice and that of the percussion. The drummer, Joshua Qumangapiq of Mittimatalik, was born in 1905; he was recognized by his peers as being a valuable source of knowledge about the traditional Inuit ways.9 This version supports the view that the older performers tend to treat the voice and percussion as stratified lines.10

In contrast, in the version of “I’m So Happy” numbered 5b-4 (recorded in 1985) the drummer keeps approximately the same beat as the singer (the voice and the drumbeat with the quarter note at a rate of 116 beats per minute), separating only occasionally when the singer’s rhythm fluctuates more than the drummer’s. The performers of this version are singer Koonoo Ipirq and drummer David Kalluk of Ikpiarjuk, who play together frequently. Kalluk, born in 1945 (two generations later than Qumangapiq), speaks English and has had a lot of contact with white music through the country music that prevails on the radio. The steady pulse of Kalluk’s drumming in synch with the singing may be partially accounted for by his exposure to Western music and the familiarity that developed from working closely with Ipirq (born in 1931).

A common performance practice used by the drummer in both versions of the song “I’m So Happy” performed with percussion (that is 5b-14 and 5b-4) is the interjection of periodic yells. In Kalluk’s case, he actually says, “Yahoo,” a decidedly white influence on an otherwise Inuit text.

Ramón Pelinski presents an interesting “test” of an approach to determine if a Westerner can produce a pastiche of an Inuit drum-dance song by following the rules set out by its generative grammar (1981: 157–200). Using the song “I’m So Happy” as a base, one could attempt to “create” a strophic song that uses an octave range, has a pentatonic scale ( -G-F-D-C), and creates a three-motive structure made up of a meandering contour (motive A), a descending contour (motive B), and ending with a plateau or relatively flat-line contour (motive C). The plateau contour is sung to the vocable ayaya that has tone reiterations on the tonal center (the interval a fourth above the lowest pitch in the song). The singer varies repetitions according to the text, employing numerous tone reiterations on the tonal center, and uses a series of eighth notes with a quarter-note pulse in a moderate tempo. Longer note values occur at the ends of strophes, and subsequent strophes begin with an incipit that repeats the tonal center that prevails in the C motive that precedes the incipit. The text is paramount. Thus, one could create a “pastiche” that can be considered representative of a “typical” drum-dance song from the Iglulik area.

-G-F-D-C), and creates a three-motive structure made up of a meandering contour (motive A), a descending contour (motive B), and ending with a plateau or relatively flat-line contour (motive C). The plateau contour is sung to the vocable ayaya that has tone reiterations on the tonal center (the interval a fourth above the lowest pitch in the song). The singer varies repetitions according to the text, employing numerous tone reiterations on the tonal center, and uses a series of eighth notes with a quarter-note pulse in a moderate tempo. Longer note values occur at the ends of strophes, and subsequent strophes begin with an incipit that repeats the tonal center that prevails in the C motive that precedes the incipit. The text is paramount. Thus, one could create a “pastiche” that can be considered representative of a “typical” drum-dance song from the Iglulik area.

Even, however, to someone with a thorough knowledge of the Inuit language, the texts that determine the musical material of traditional songs are allusive at best, referring to events that were commonly known only at the time of composition, which was why the story behind the song was always requested (although seldom known by my consultants in 1985). One can deduce from the ethnographic literature and an analysis of the corpus of 315 songs what are the preferred musical occasions, type of drum, scales, ranges, forms, tonal centers, melodic contours, tempos, and concordances of Iglulik Inuit drum-dance songs. But one cannot actually know how the Inuit composed their songs. Over time there has been a whole repertoire of melodies used in drum-dance songs. The language itself influences the way that a person from a particular culture will shape his or her ideas in sound. According to the Netsilik Inuit poet Orpingalik: “Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces and ordinary speech no longer suffices” (Rasmussen 1931: 321).

The drum-dance songs are a way for the Inuit to maintain a link with their past. There are also instances of traditional music being used in modern settings. The Anglican priest in Mittimatalik set biblical words to the tune of a drum-dance song, and the song was performed during the Easter ceremonies in 1976. Northern rock bands occasionally use Inuit melodies. On the compact disc Nitjautiit (The People’s Music), Inuit singer Susan Aglukark performs the song “Old Stories,” which combines ayaya with boogie-woogie (1991: cut 29).

Although there is no doubt that white culture has made major inroads into the traditional way of life of the Inuit, elements of traditional song still come through. Present-day Inuit composers continue to find ways to express themselves that honor the old ways while selectively utilizing musical influences from the dominant white culture to help get their message across to a contemporary audience. The recontextualization of the ayaya repertoire over time has proved to be an effective strategy for preservation, much as their ancestors used traditional drum-dance songs to ensure the transmission of information about the past to future generations.

1. The native term Inuit means “the people.” It has replaced the older term Eskimo that was formerly used to designate people of the Arctic, an Algonquian Indian term that means “eater of raw meat” that many Inuit people found offensive.

2. When the new territory of Nunavut (Our Land) in the eastern Canadian Arctic was created in 1999, the names of the communities reverted to their original Inuit designations. The hamlets under study are Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik—“the resting place of Mittima”), Arctic Bay (Ikpiarjuk—“the pocket,” referring to the mountains surrounding the hamlet by the water), and Igloolik—“a place with igloos” (Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate: n.p.).

3. The compact disc Songs of the Inuit Iglulik: Canada (2004) includes sixteen drum-dance songs from this corpus.

4. The term consultant refers to the Inuit performers of song and dance who agreed to be recorded or interviewed for this project.

5. An explanation of the symbols for song number 5d-84.PI77–10 follows: “5” refers to a five-note scale pattern; “d” is the fourth scale pattern; “84” means that this is the eighty-fourth song using this scale pattern; “PI” refers to Pond Inlet (Mittimatalik), where the song was collected (“AB” indicates Arctic Bay [Ikpiarjuk], and “IGL” indicates Igloolik); “77” is 1977, indicating the year the song was collected; and “10” signifies that this is the tenth song collected on this particular field trip.

6. These drum measurements are from a survey I conducted of twenty-seven drums from across the Arctic housed at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec.

7. Since northern Baffin Island is above the timberline, in precontact times drum frames were made from a curved bone, usually from a whale.

8. In Ikpiarjuk in 1985, the two male drum dancers who performed for me also did not sing, and my consultants reported that this was the norm.

9. Joshua Qumangapiq was respected not only as a drum dancer and bearer of culture in regards to drum-dance songs but also as a shaman (priest) with a large repertoire of sacred songs. When I was collecting songs in Ikpiarjuk in 1985, Levi Kalluk, also a shaman, had the largest repertoire of drum-dance songs, and his songs consistently had the most verses.

10. Drum dancer Aglak Atitat (whose age was “around sixty-five” in 1985) also drummed in a rhythm that was relatively independent of the singer’s pace when compared with younger performers. I was told that Atitat frequently passed on knowledge of the old ways to the young people. He regularly gave workshops at the elementary school in Ikpiarjuk about how to make a drum, how to build a kayak, and so on, and he told the old stories to the children. Since Inuit children are taught in their own language, Inuktitut, for the first three years of school, they were able to understand Atitat’s stories, whose own childhood predated the establishment of federal schools on Baffin Island with the result that he never learned English.

Aglukark, Susan. 1991. Nitjautiit [The People’s Music]. LP Record CBC-CD3. Compact disc.

Cavanagh, Beverley [Diamond]. 1982. Music of the Netsilik Eskimo: A Study of Stability and Change. Vol. 1. Mercury Series no. 82. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.

Conlon, Paula Thistle. 1992. “Drum-Dance Songs of the Iglulik Inuit in the Northern Baffin Island Area: A Study of Their Structures.” Ph.D. diss., University of Montreal.

Ikaliiyuk, Rose. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.

Iyetuk, Isadore. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.

Kalluk, David. 1985. Personal communication with Paula Conlon in Ikpiarjuk. Kalluk, Levi. 1985. Personal communication with Paula Conlon in Ikpiarjuk. Kupak, Michel. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.

Lutz, Maija M. 1978. The Effects of Acculturation on Eskimo Music of Cumberland

Peninsula. Mercury Series no. 41. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. Mary-Rousselière, Guy. 1984. “Iglulik.” In Handbook of North American Indians, edited by David Damas and William Sturtevant, 5:431–46. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. n.d. “Nunavut: Canadian Arctic.” http://www.arcticomi.ca/index.html.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1988. “La danse à tambour chez les Inuit igloolik (nord de la Terre de Baffin).” Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec 18, no. 4: 37–48.

NWT. 1990–91. Northwest Territories Data Book, 1990–91. Yellowknife, Northwest Territories: Outcrop.

Panipakoochoo, Letia. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Mittimatalik.

Pelinski, Ramón. 1981. La musique des Inuit du Caribou: Cinq perspectives méthodologiques. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Qango, Isapee. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Mittimatalik.

Quassa, François. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.

Rasmussen, Knud. 1929. “Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos.” In Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921–24. Vol. 7, paper 1. Copenhagen: Gyldendal-Nordisk.

——. 1931. “The Netsilik Eskimos.” In Report of the Fifth Thule Expedition, 1931. Vol. 8, papers 1–2. Copenhagen: Gyldendal-Nordisk.

Songs of the Inuit Iglulik: Canada. 2004. Witness World PG 1107. Blue Moon Producciones Discograficas (Barcelona), DL B-47952/04. Compact disc.

Suluk, Donald. 1983. “Some Thoughts on Traditional Inuit Music.” Inuktitut 54: 24–30.

Urrunaluk, Noah. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.

Uyarak, Joanasie. 1977. Personal communication with Jean-Jacques Nattiez in Igloolik.