The cities of Nice, Cannes and Monte Carlo dominate one of the most celebrated stretches of coastline in the world, a 50km (30-mile) strip where heavily built-up resorts are interspersed by exclusive peninsulas, home to the happy few, and bordered on the interior by the arrière-pays of medieval hill villages and Alpine foothills. If you’re not jet-setting by yacht or helicopter between the three, they are well connected by railway, by the A8 autoroute and the coastal roads, notably the spectacular trio of corniches between Nice and the Italian frontier, with hairpin bends and stunning sea views.

Brightly coloured houses line the streets of Monaco

iStock

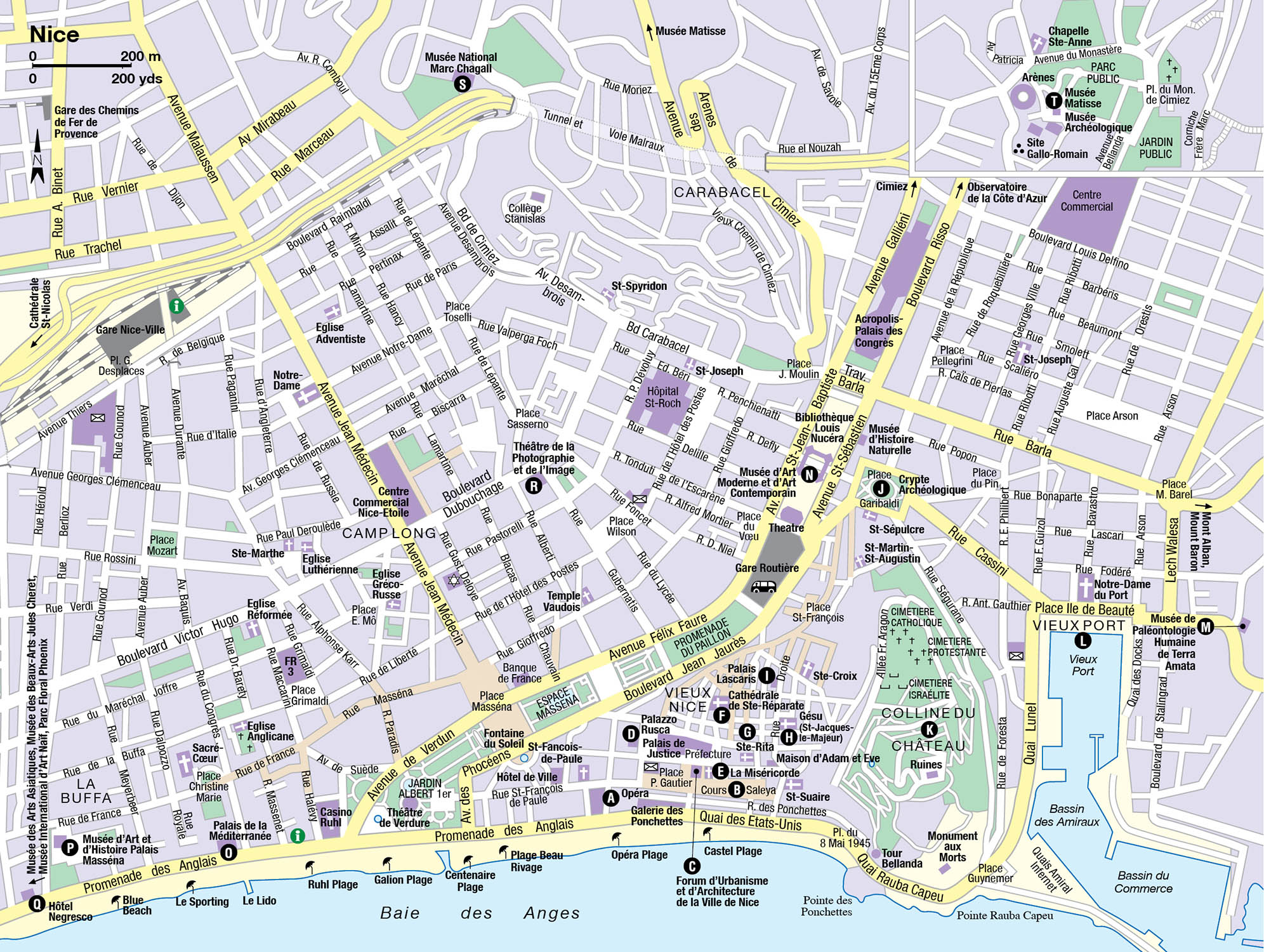

Nice

With a splendid position curving along the broad sweep of the Baie des Anges, Nice 1 [map] merits its reputation as the Queen of the Riviera or its affectionate Nissart name, Nissa la Bella. Central Nice divides neatly into two parts: Italianate Vieux Nice, beneath the Colline du Château, to the east of the River Paillon; and the elegant New Town, which grew up in the 19th and early 20th centuries behind the promenade des Anglais to the west. Beyond, Nice extends over a series of hills – Cimiez, Les Baumettes, Piol, Fabron – where urbanisation has largely taken over olive groves and villa gardens.

Note that all municipal museums in Nice are no longer free as of January 2015; their entrance fee is now €10 but there is also a pass which will save you money if visiting more than two museums (for more information, click here).

Vieux Nice

Against a backdrop of colourful houses, Baroque churches and campaniles, the picturesque Old Town mixes Nice at its most traditional, where some elderly residents still speak Nissart (an Occitan language related to Provençal) and restaurants serve local specialities that appear not to have changed for generations, alongside bohemian bars, art galleries and clothes shops reflecting the young cosmopolitan set that has rejuvenated the district.

Enter Vieux Nice on rue St-François-de-Paule, reached from place Masséna or the Jardin Albert I, passing the town hall, the chic Hôtel Beau Rivage (where Matisse stayed on his first visit in 1917) and the elaborate pink-columned facade of the Opéra de Nice A [map] (www.opera-nice.org), rebuilt in 1884 on the site of the earlier opera house, gutted when the stage curtain caught fire. Across the street, family-run Maison Auer (for more information, click here) has been producing candied fruits and chocolates since 1820, while Alziari (for more information, click here) draws connoisseurs for its olive oil, produced at its own mill in the west of the city and sold in decorative tins.

The imposing facade of the Opéra de Nice

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Cours Saleya

The street leads into broad cours Saleya B [map] and the colourful flower market (Tue–Sun 6am–5.30pm) and fruit and vegetable market (Tue–Sun 6am–1.30pm), held under bright striped awnings, where laden stalls reflect the profusion of Riviera produce. Along with the tourists, the market is still frequented by local residents and the town’s best chefs.

Fruit stall in cours Saleya

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

The market spreads into adjoining place Pierre Gautier, where you’ll find many stalls run by local producers, selling nothing but lemons or delicate orange courgette flowers. On Monday, the fruit and vegetables are replaced by antiques and bric-a-brac stalls. On one side, the Forum d’Urbanisme et d’Architecture de la Ville de Nice C [map] (Mon 1.30am–5pm, Tue–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat 10am–1.30pm; free) holds interesting exhibitions about Nice’s architectural heritage and urban projects. At the back of the square, the colonnaded former Palace of the Kings of Sardinia was built by the King of Piedmont when Nice was returned to Sardinia after the Revolution, and now serves as the Préfecture of the Alpes-Maritimes. Next door, the white stone Palais de Justice opens onto place du Palais, facing the russet-coloured Palazzo Rusca D [map], a Baroque mansion with impressive triple-storey arcades on one side and an 18th-century clock tower on the other. There is a second-hand book market on the square on the first and third Saturday of each month.

Cours Saleya is bordered on the sea side by Les Ponchettes, a double alley of low fishermen’s cottages, with archways leading through to quai des Etats-Unis. Amid restaurants and a couple of exclusive shops, two vaulted halls play host to municipal exhibitions of contemporary art: Galerie des Ponchettes and Galerie de la Marine (both Tue–Sun 10am–6pm). About halfway along cours Saleya, the Chapelle de la Miséricorde E [map] (Tue 2.30–5.30pm; free) is generally considered the finest of all Nice’s Baroque interiors. It belongs to the pénitents noirs, one of the religious lay fraternities that still thrives in the town, but is only open for extremely limited hours. Further along, on the corner with rue de la Poissonnerie, is the Adam and Eve house, one of the oldest buildings in the city, decorated with a Naïve 16th-century relief of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

Heart of the Old Town

However, it is in the grid of narrow, shady streets behind cours Saleya where you get a real feel for the atmosphere of Vieux Nice. Although the population started moving down from the Colline du Château in the 13th century, the town was almost entirely reconstructed in the 17th and 18th centuries, giving it much the appearance it has today: for the most part tall, simple facades in tones of yellow and orange, punctuated by Baroque churches and the occasional fine carved doorway.

Vieux Nice architecture

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

In the heart of Vieux Nice, lively place Rossetti has a dual appeal: the ice creams and sorbets of Fenocchio (www.fenocchio.fr), where more than 90 flavours range from classic coffee and pistachio to rose, jasmin and even poppy; and the sculpted facade of Cathédrale Sainte-Réparate F [map] (Tue–Fri 9am–noon, 2–6pm, Sat until 7.30pm, Sun 9am–1pm, 3–6pm; free; http://cathedrale-nice.fr), built on a cruciform plan in the 1650s. It is dedicated to early Christian martyr Saint Reparata, the city’s patron saint, whose body, accompanied by two angels (hence the name Baie des Anges) is said to have arrived here by boat after drifting across the Mediterranean from Palestine, where she had been decapitated at the age of 15. Despite its impressive painted dome over the transept and numerous Baroque side chapels, the Niçois prefer the cheerful little Eglise Sainte-Rita G [map] (Mon–Sat 7am– noon, 2.30–6pm, Sun 8am–noon, 3–6pm; free; www.sainte-rita.net) on rue de la Poissonnerie, an intimate gem, with a skylit half-dome and profusion of sculpted saints, barley-sugar columns and sunbursts. Take a look also at the arcaded Loggia Communale, dating from 1574, around the corner on rue de la Préfecture.

The much-loved Eglise Sainte-Rita.

Shutterstock

From here, rue Droite, once the main thoroughfare, leads to the Eglise Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur or Eglise du Gésu H [map] (Tue 3–7pm, Thur 3–5.30pm, Sat 9am–noon, 3–6pm; free), built by the Jesuit order in 1612. It set the model for Nice’s Baroque churches, with its single-naved interior full of stucco cherubs and stripy painted marble, although the blue-and-white classical facade is a later reworking. Further up the street at No. 15 is the Palais Lascaris I [map] (Wed–Mon 10am–6pm), the 17th-century Genoese-style mansion of the Lascaris-Ventimille family and Nice’s grandest secular Baroque building. The sober street facade does not prepare you for the splendour of the interior, with its magnificent vaulted stairway, decorated with sculptures and frescoed grotesques. On the second floor, staterooms, furnished with Baroque furniture and tapestries, have spectacular painted ceilings with mythological scenes: Venus and Adonis, the Abduction of Psyche and the Fall of Phaethon, where youth and horses tumble from the sky amid a mass of swirling clouds. The first floor has been renovated to house the town’s extensive collection of 18th- and 19th-century musical instruments.

The tram from place Garibaldi.

Shutterstock

Higher up, rue Droite runs into rue St-François and the place St-François, home to a small fish market every morning except Monday. The 17th-century former Palais Communal is now a trades union building. Further along, rue Pairolière is busy with food shops and typical Niçois bistros, while on the corner of rue Miralheti, customers queue up for plates of socca (for more information, click here) and other Niçois snacks at ever-popular Chez René Socca.

Independence hero

Giuseppe Garibaldi, hero of Italian independence, was actually born in Nice in 1807. Although as a convinced republican he helped the French in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, he had earlier opposed the attachment of Nice to France, which is said to be why his statue in place Garibaldi faces towards Italy.

On the northern edge of Vieux Nice, the handsome place Garibaldi J [map], with arcaded facades and the neoclassical Chapelle du Saint-Sépulcre, was laid out in the 1780s by the King of Sardinia, Victor-Amédée, to create a monumental entry to the town on the completion of the royal carriageway from Turin. Originally called Piazza Vittoria, it was renamed in honour of the Nice-born hero of Italian reunification whose statue stands in the middle. Note that Garibaldi is facing Italy, while beneath him two bronze women carry a baby, presumably the infant nation. Excavations during the construction of the tramway in 2007 revealed part of the antique port, aqueduct, moat and bastion. The 2,000-sq metre underground attraction is now open to the public as the Crypte Archéologique (entrance from Place Jacques Toja; Tue–Sun, 55-minute guided tours at 10 and 11am and at 2, 3 and 4 pm; no children under 7 allowed and flat shoes required; reservation obligatory, contact the Centre du Patrimoine, tel: 04 92 00 41 90 or online at www.centredupatrimoinevdn.tickeasy.com).

The Colline du Château

Reached by assorted steep stairways from Vieux Nice, by tourist train from the quay in front of Jardin Albert I, by lift (daily Apr–May and Sept 8am–7pm, June–Aug 8am–8pm, Oct–Mar 8am–6pm; free) or by stairs at the end of quai des Etats-Unis, the Colline du Château K [map] was for centuries the heart of the medieval city that grew up around the castle, before the population moved down to the plain. Today nothing remains of the citadel, razed in 1706 on orders of Louis XIV, but the remaining mound provides a shady interlude on hot summer days, and plenty of gorgeous views over the bay. Follow the sound of water up to the cascade that tumbles dramatically over a man-made lump of rock. Below lie an amphitheatre, a café, children’s playgrounds and the poorly indicated ruins of the medieval cathedral and the residential district destroyed in the siege of 1691. Slightly down the hill to the north are two graveyards: the Jewish cemetery with its funerary stelae, and the Catholic cemetery (which also includes Orthodox and Protestant tombs of some of the town’s noble émigrés), which resembles a miniature city with gravel paths and a forest of elaborate 19th-century monuments to Niçois notables. Overlooking the sea, at the top of the lift is the solid round Tour Bellanda, a mock fortification reconstructed in the 19th century, where Hector Berlioz lived while composing his King Lear Overture. It occasionally opens to the public for exhibitions on the city’s heritage.

Midday cannon shot

Every day at noon, a resounding boom announces the midday cannon shot fired from the Colline du Château. The tradition was inaugurated by Sir Thomas Coventry-More in the 1860s to ensure that his forgetful wife returned home in time to prepare lunch, and was perpetuated by the municipality in 1871.

The view over the Vieux Port from the Colline du Château

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

The Vieux Port

Back at sea level, quai Rauba Capéu (Nissart for ‘flying hat’, because of the breeze) curves around the castle mound past a striking World War I war memorial set into its cliff face, to the picturesque Vieux Port L [map]. The port can also be reached from place Garibaldi along rue Ségurane, known for its cluster of antiques dealers and bric-a-brac shops. Framed by the castle hill on one side and Mont Boron on the other, the Bassin Lympia was dug out in the late 18th century (before that fishing boats were simply pulled up on the shore and Nice’s main port was at nearby Villefranche-sur-Mer). At the same time, beautiful arcaded place de l’Ile de Beauté was built along the north side in Genoese fashion, with deep-red facades and ornate trompe l’œil window frames, on either side of the neoclassical sailors’ church Eglise Notre-Dame-du-Port (Mon–Fri 9am–noon, 3–6pm, Sun 9am–noon). More tranquil than Vieux Nice, the restaurants along the eastern quay, mostly specialising in fish, are popular. Departure point for ferries to Corsica, the port has recently been the subject of debate over controversial plans to expand it for giant cruise ships, but it has now been decided to leave it as a yachting marina and construct a new commercial port on the western side of town.

Just east of the port on boulevard Carnot, at the start of the Basse Corniche, is a curious but fascinating museum, the Musée de Paléontologie Humaine de Terra Amata M [map] (Wed–Mon 10am–6pm; www.musee-terra-amata.org), situated at the bottom of an apartment block on the very spot where a tribe of elephant-hunters briefly made their settlement on the beach 400,000 years ago when the sea level was 26m (84ft) higher than today.

When the site was discovered in 1966, archaeologists worked day and night for five weeks before it was built on. The centrepiece is a large cast made of the ground, showing traces of tools, debris, animal bones and even a footprint left behind, while other exhibits include axeheads, flint tools and a reconstructed twig hut.

Beyond here wooded Mont Boron conceals luxurious residences and 11km (7 miles) of public footpaths. At the top of the hill, the 19th-century military fort is set to be transformed into an architecture centre by architect Jean Nouvel.

Promenade du Paillon

Created when the River Paillon was covered over as a hygiene measure in the 19th century, the promenade du Paillon marks the divide between Vieux Nice on one side and the New Town on the other. At its centre, place Masséna forms the symbolic heart of Nice, with elegant arcaded facades in Pompeian red, laid out in the 1840s as part of the urbanisation plan of the Consiglio d’Ornato, the council designated by King Charles-Albert in Turin to mastermind the expansion of the city. Long a traffic-clogged junction, the square was repaved and pedestrianised for the opening of the tramway in 2007, with the installation of an artwork by Spanish artist Jaume Plensa, with seven resin figures atop tall metal poles, which symbolise the different continents and are illuminated in a colourful glow at night.

Figures atop metal poles preside over place Masséna

iStock

Elegant place Masséna

Fotolia

Towards the sea, the pleasant shady Jardin Albert I contains the Théâtre de Verdure, an outdoor amphitheatre used for summer concerts, and a massive bronze arc sculpture by Bernar Venet that seems to float over the lawn.

Promenade des Arts

On the other side of place Masséna, the promenade du Paillon leads to the promenade des Arts, created in the 1980s by mayor Jacques Médecin as part of his ambitious cultural programme. Designed by architects Yves Bayard and Henri Vidal, the Carrara marble complex comprises the Théâtre National de Nice, a terrace with sculptures by Calder, Borovsky and Niki de Saint Phalle’s mosaic Loch Ness Monster fountain, and the Musée d’Art Moderne et d’Art Contemporain N [map] (MAMAC; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; guided tours on Wed at 3pm; www.mamac-nice.org). The building looks rather harsh from outside but the galleries inside, where four wings are connected by glass bridges, provide a luminous setting for works from the 1960s to the present. The museum’s strength lies in its collection of the Ecole de Nice, including an entire room of Yves Klein’s monochromes, blue sponges and fire paintings, works by Ben, Raysse, Malaval and Christo, Arman’s accumulations and cut-up musical instruments and an exceptional donation by Niki de Saint Phalle, which is complemented by parallel movements in American Pop Art, including works by Warhol, Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg.

The Ecole de Nice

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Nice shot to the forefront of artistic creation in France, around the trio Yves Klein, Arman and Martial Raysse, championed by critic Pierre Restany, and later joined by César, Sosno, Ben, Niki de Saint Phalle and Robert Malaval. Although associated with Nouveau Réalisme (the French equivalent of Pop Art), Fluxus and Supports-Surfaces, the Ecole de Nice was more about a sense of energy and sometimes anarchist attitudes than a stylistic school. The pivotal figure was Yves Klein (1928–62), who combined painting and art actions in his famous monochromes in trademark IKB (International Klein Blue), and anthropométries, where female models covered in paint were rolled like a living paintbrush over the canvas. Unlike most earlier modern artists who found inspiration in the south, this was a home-grown movement: Klein, Arman and Malaval were born in Nice, César and Sosno in Marseille, Raysse at Golfe Juan. As Klein remarked in 1947: ‘Even if we, the artists of Nice, are always on holiday, we are not tourists. That is the essential point. Tourists come here for the holidays; as for us, we live in this holiday land, which is what gives us our touch of madness. We amuse ourselves without thinking about religion or art or science.’

Ringing the changes at the MAMAC

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Across the street on boulevard Risso, the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; www.mhnnice.org) harks back to a decidedly different era, with stuffed birds, botanical specimens and minerals illustrating the Mediterranean habitat. In order to showcase more of its huge collection, the museum is due to relocate to a new purpose-built home in Parc Phoenix but there is no firm moving date at the time of writing.

To the north, the promenade des Arts’ latest addition is heralded by the bizarre vision of the Tête Carrée, a massive 30m (96ft) high head by sculptor Sacha Sosno, described by the artist as ‘an inhabited sculpture’, which morphs into a cube containing the offices of the Bibliothèque Louis Nucéra (public library), the books and public entrance are actually underground. Beyond, before the river finally resurfaces, are the Acropolis congress and exhibition centres, opened in the 1980s, making Nice a major venue for international trade fairs and conferences.

The New Town

West of the Paillon, the New Town grew up in the 19th and early 20th centuries behind the promenade des Anglais, laid out in a grid of broad avenues and garden squares roughly following the plan conceived by the Consiglio d’Ornato, planted with the exotic palms, citrus trees and bougainvillaea that have acclimatised in the south of France. After the narrow streets and deep shadows of Vieux Nice, the atmosphere here is airy and bright. Although the street plan is regular, the architecture is anything but, making this area a delight for walkers.

Promenade des Anglais

With blue chairs, white pergolas, palm trees and Belle Epoque architecture, the promenade des Anglais has come to symbolise the elegance of Nice – not bad for what began in 1822 as an employment exercise, when the Reverend Lewis Way opened a public subscription to construct a new footpath along the shore, linking the Old Town to the British colony that had settled on the hills further west. The promenade took on its present appearance in the 1930s when the thoroughfare was widened. Despite busy traffic, it remains a favourite place to walk, not just for the sea views but for the diversity of those who use it, from roller-bladers to elderly ladies, and for the splendour of its grand hotels, although few restaurants or boutiques line the promenade.

Sunbathing on a public beach

Shutterstock

Beaches for All

With 15 beach concessions running along the Baie des Anges, Nice’s private beaches are about much more than just swimming and sunbathing, although the sun loungers (chaises longues) can be a boon on the uncomfortable pebbles. Castel Plage on quai des Etats-Unis at the eastern end of the Baie des Anges calls itself ‘the beautiful beach for beautiful people’ and likes to promote its arty image with chess matches and art exhibitions; Beau Rivage (www.hotelnicebeaurivage.com), belonging to the elegant Vieux Nice hotel, has a vast restaurant serving a modern Med-Asian fusion cuisine, with a DJ in the afternoons and jazz on Sundays; Blue Beach (www.bluebeach.fr), opposite Hôtel Negresco, is a chic place to dine by night and a child-friendly beach by day, with table tennis, a popular seawater pool for kids and water sports next door; while trendy Hi Beach (www.hi-beach.net), is split into lifestyle zones – Play for families, with sandpit and anti-UV cabins for babies; Relax, with plants and hammocks; Energy around the bar – plus computers, books and magazines, yoga and massages, solar-powered showers and a sushi bar.

Running westwards from Jardin Albert I, where the Méridien Nice and neighbouring Casino Ruhl controversially replaced the old Hôtel Ruhl in the 1970s, admire the Art Deco facade of the Palais de la Méditerranée O [map] at No. 15. Built in 1929 for American millionaire Frank Jay Gould, it epitomised 1930s glamour with a casino, theatre, restaurant and cocktail bar. The Palais closed in 1978 and was gutted before reopening with a modern hotel, apartments and casino behind the listed facade. At No. 27, the pink stucco Westminster still has its grandiose reception rooms, while Hôtel West End (No. 31) was the first of the promenade’s grand hotels, opened in 1855.

Next door, set back from the promenade at the rear of a luscious garden laid out by Edouard André, the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire Palais Masséna P [map] (Wed–Mon 10am–6pm), built in 1898 for Prince Victor Masséna, grandson of one of Napoleon’s generals, has been renovated as a museum devoted to the Belle Epoque past. On the ground floor are grandiose reception rooms, with Empire furniture, sumptuous inlaid panelling and a full-length portrait of Napoleon. Upstairs, the aristocrats, artists and intellectuals who shaped 19th-century Nice are portrayed in an eclectic array of portraits, paintings, documents and memorabilia, including the cloak worn by Josephine when Napoleon was crowned King of Naples, and paintings of Old Nice. Among curiosities are a poster, in French and Italian, calling citizens to vote in the referendum for Nice to rejoin France in April 1860.

On the other side, Nice’s grandest hotel, the Hôtel Negresco Q [map], is an institution with its pink-and-green cupola and uniformed doormen. Designed by Edouard Niermans, with a glazed verrière by Gustave Eiffel over the salon, it was one of the most modern hotels in the world when it opened in 1913, with lavish bathrooms and telephones in the rooms; but with the outbreak of war in 1914 it was transformed into a hospital and Romanian owner Henri Negresco was ruined. Still a favourite with politicians and film stars, the hotel is endearingly idiosyncratic, with antique furniture, carousel horses and a kitsch souvenir shop.

The opulent Hôtel Negresco is a Nice institution

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Across the New Town

Parallel to the promenade des Anglais, broad avenue Victor Hugo is a panorama of New Town architecture, from classical villas with wrought-iron balconies and a neo-Gothic church to carved friezes, ornate Belle Epoque rotundas, Art Deco mansion blocks and streamlined 1950s zigzags. Between here and the station is the quieter Musicians’ Quarter, with streets named after composers and the circular Escurial Art Deco apartment block. On the eastward continuation of avenue Victor Hugo, the Théâtre de la Photographie et de l’Image R [map] (27 boulevard Debouchage; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; www.tpi-nice.org) stages excellent photographic exhibitions. The building itself is worth a look, with a decorative theatre and neo-Renaissance ceilings.

Just off place Masséna, the Carré d’Or, formed by avenues de Suède and Verdun, rue Masséna and rue Paradis (and its extension, rue Alphonse Karr), is home to Nice’s smartest clothes shops. Pedestrianised rue Masséna and adjoining rue de France form an animated hub with chain stores and pizzerias.

Avenue Jean-Médecin, the busy tree-lined shopping street that runs north from Masséna towards the station, has slid downmarket since it was laid out on the Haussmannian model with grand department stores, banks and opulent cafés. However, since the street has recently been pedestrianised it may now rediscover its aura of old.

Bank heist

France’s biggest ever bank heist took place at the Société Générale on avenue Jean-Médecin in 1976, when Albert Spaggiari climbed through the sewers and tunnelled into the vault, leaving with 50 million francs (about 24 million euros). Arrested months later, he escaped from police custody to South America, publishing his autobiography and fraternising with Ronnie Biggs.

Western Nice

On the Beaumettes hill, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice (33 avenue des Baumettes; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; combined ticket with the Musée International d’Art Naïf Anatole Jakovsky; www.musee-beaux-arts-nice.org) occupies an extravagant mansion built in 1878 for the Ukrainian Princess Elisabeth Kotschoubey, which gives some idea of the grandeur in which the foreign aristocracy lived. Downstairs, the Old Masters section ranges from medieval religious panel paintings to 18th-century canvases by Natoire and Van Loo. Look out for two highly detailed allegorical landscapes of Water and Earth by ‘Velvet’ Brueghel, swarming with fantastical animals and birds, and a bravura fantasy portrait by Fragonard. At the top of the stairs, past plaster studies by Carpeaux, the 19th- and 20th-century collections include romantic pastels by Jules Chéret, best-known as a decorator and poster artist, Symbolist paintings by Gustave-Adolphe Mossa, the museum’s first curator, Impressionist works by Monet and Sisley, striking portraits by Kees van Dongen, a room of cheerful seaside scenes by Raoul Dufy, and numerous paintings by Russian artist and diarist Marie Bashkirtseff. The Baumettes hill itself is worth a wander for the villas erected by British and Russian aristocrats, including the pink mock-medieval Château des Ollières and the Château de la Tour.

A take on The Three Graces at the Musée des Beaux-Arts

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

The Musée des Beaux-Arts’ grandiose exterior

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Further west, in a villa owned by perfumier François Coty in the 1920s, is the Musée International d’Art Naïf Anatole Jakovsky (avenue de Fabron; Wed–Mon 10am–6pm; combined ticket with the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nice), centred around a vast collection of Naïve art donated by the Romanian art critic Anatole Jakovsky, one of the first, along with artist Jean Dubuffet, to admire the colourful meticulous works by these self-taught artists. The collection includes a portrait by Le Douanier Rousseau, obsessively detailed paintings of Paris monuments by Louis Vivin, and other major Naïve artists including Jules Lefranc, Séraphine, Rimbert, Bombois, as well as the American Grandma Moses.

Parc Floral Phoenix

At the very westernmost end of the promenade des Anglais, just before the airport and the modern Arenas business district, the Parc Floral Phoenix (daily Apr–Sept 9.30am–7.30pm, 1–14 Oct 9.30am–7pm, 15–28 Oct 9.30am–6.30pm, Nov–Mar 9.30am–6pm) is an imaginative modern botanical garden that is enjoyable for families and plant-lovers. Around the garden you’ll find streams with stepping stones, aviaries with cranes, parrots and birds of prey, prairie dogs, an otter pool and crested porcupines. The vast polygonal, 25m (82ft) -high glasshouse – one of the largest in Europe – is a hothouse wonderland, where different zones recreate different tropical and desert climates, with magnificent palms, tree ferns and orchids, and habitats populated by giant iguanas and flamingos, as well as an aquarium and tanks of tarantulas. Sitting in the lake by the entrance to the park is the Musée des Arts Asiatiques (Wed–Mon May–mid-Oct 10am–6pm, mid-Oct–Apr 10am–5pm; www.arts-asiatiques.com; free), a striking geometrical building symbolising Earth and Sky, designed by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange. The small but high-quality collection of art from China, Japan, India and Cambodia includes ornate samurai swords and ancient Chinese bronzes and terracottas. There is an adjoining teahouse, where the Japanese tea ceremony is performed on certain weekends.

North of the Station

The arrival of the railway from Paris in 1864 hastened Nice’s rise as a destination for Europe’s aristocracy, with a station in Louis XIII-style brick and stone facings in a new district north of the centre – what is now a typical station hinterland of cheap hotels and ethnic eateries. To the west across boulevard Gambetta, in what was once the heart of the Russian district, the newly restored Cathédrale Orthodoxe Russe Saint-Nicolas (boulevard Tzarewitch; Mon–Sat 9.15am–noon, 2.30–5.30pm, Sun 2.30–5.30pm; charge), with five onion domes and glazed tiles, is a surreal apparition amid the modern apartment blocks. Inspired by St Basil’s in Moscow and inaugurated in 1912, the largest Russian Orthodox church outside Russia – and single most visited sight in Nice – was commissioned by the Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, mother of Tsar Nicolas II, when an earlier church on rue Longchamp became too small for the growing Russian community. The atmospheric interior, laden with icons, carvings and frescoes, contains a magnificent gilded repoussé copper iconostasis (the screen that separates the congregation from the sanctuary reserved for the clergy). In the grounds is a small chapel (Wed 2.30–6pm) built on the spot where Grand Duke Nicolas Alexandrovich, son of Alexander II, died in 1865 aged 21. Nearby on avenue Paul Arène, you can also spot the 1902 Hôtel du Parc Impérial, which was originally destined for Russian families wintering in the town but became a lycée after World War I.

The onion-domed Russian Orthodox cathedral

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

On avenue Bourriglione, the extraordinary Eglise Jeanne d’Arc (daily 10am–6pm) is exotic in a different way. An architectural one-off, the avant-garde white concrete church designed in the 1930s by Jacques Droz resembles a box of eggs with its cluster of ovoid domes. The parabolic interior is decorated with murals by Eugène Klementieff and stylised concrete sculptures of Joan of Arc and the Crucifixion by Carlo Sarrabezolles, a pioneer in sculpting directly into wet concrete. Further north, in a 17th-century Italianate villa, largely disguised by a radical raw concrete and pebble extension, the Villa Arson, Centre National d’Art Contemporain (20 avenue Stéphen Liégeard; Wed–Mon 2–6pm, July–Aug until 7pm; www.villa-arson.org; free) is home to one of France’s most adventurous art schools and exhibition centres.

Cimiez

Smart residential Cimiez is where Nice feels closest to its Belle Epoque spirit. Northeast of the centre by boulevard Carabacel and boulevard de Cimiez, this is a district of winding streets that meander uphill, lined with stucco villas amid lush gardens and palm trees. On avenue Docteur Ménard is the Musée National Marc Chagall S [map] (Wed–Mon May–Oct 10am–6pm Nov–Apr 10am–5pm; www.musee-chagall.fr), where paintings by Chagall are set off by the beautifully designed low modern building and surrounding Mediterranean garden. Inaugurated in 1973, it was the first time a national museum in France had been devoted to a living artist.

Enjoying a leisurely game of pétanque in Cimiez

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

It was created for his series of 17 scenes from the Old Testament, which reveal Chagall’s unique ability to combine colour and narrative with a personal iconography. In another room are five rose-tinted paintings of the canticles dedicated to ‘Vava’, his wife Valentina Brodsky, and in the auditorium are three intense stained-glass windows and related studies depicting The Creation of the World.

Almost across the street, on boulevard de Cimiez, the fine Belle Epoque Villa Paradiso now belongs to the town’s education service, but is surrounded by pretty public gardens. Further up the boulevard you can spot the White Palace and the Alhambra (distinguished by its two mosque-like minarets), grand former hotels built in the days before sea bathing became popular, when this was the most fashionable part of town to stay.

At the top of the boulevard de Cimiez, the ornate Hôtel Excelsior Régina, by architect Biasini, was built in 1896 in anticipation of a visit by Queen Victoria. The queen in fact stayed here twice, occupying the entire west wing with a suite of more than 70 rooms, an event commemorated in the crown over the entrance and a marble statue outside. Converted into apartments in the 1930s, this is where Matisse lived at the end of his life, sketching on the ceiling from his bed with a brush attached to a long pole.

Nice Observatory

Charles Garnier and Gustave Eiffel, two of the 19th century’s greatest architects and engineers, collaborated in the construction of the Nice Observatory on Mont Gros, east of the city above the Saint-Roch district. Still at the cutting edge of research, it is open for guided visits (Wed, Sat, Sun 2.45pm; www.obs-nice.fr).

Roman Remains

Across the street are the scant remains (entrance tunnels, a few tiers of seats) of the Roman amphitheatre, which once seated 5,000 people and is now used for the Nice Jazz Festival each summer (for more information, click here). To get a clearer idea of Nice’s Roman incarnation as the city of Cemenelum, visit the adjacent Musée Archéologique (Wed–Mon 10am–6pm), which has displays of statues, glassware and jewellery excavated in the area and, in the basement, sarcophagi and inscribed stelae from a nearby necropolis, as well as the chance to try out some Roman board games.

The most interesting part of the museum is the archaeological site outside, where extensive remains include some imposing walls and canals and pieces of hypocaust (the underfloor heating system) from three bathing complexes dating from Cemenelum’s 3rd-century heyday, as well as a 5th-century palaeo-Christian baptistery.

Homage to Matisse

Behind the ruins, you can spot the rust-coloured Genoese villa that houses the Musée Matisse T [map] (164 avenue des Arènes; Wed–Mon 10am–6pm; www.musee-matisse-nice.org), though the entrance is around the corner, reached through a grove of ancient olive trees. The extensive collection hung around the house and in the discreet underground modern extension spans the artist’s entire career from early paintings of the 1890s to his late paper cut-outs, allowing one to see how he assimilated such inspirations as Riviera sunlight, patterned textiles, classical sculpture and voyages to North Africa and Tahiti.

The rust-coloured facade of the Musée Matisse

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Highlights include Fauve portraits, the vibrant Still Life with Grenadines, small oil studies for different versions of La Danse, Odalesque au Coffret Rouge, a series of small bronze heads of Jeannette, and the colourful late cut-out Flowers and Fruit, made in 1953.

Pay further homage to Matisse in the simple slab-like tomb that sits on its own terrace in the gardens of the Cimiez Cemetery just up the road, the burial place for many British and Russian aristocrats. Painter Raoul Dufy is also buried here, although on the other side of the cemetery. You can admire fine views of the hills of Nice and down to the coast from the adjoining rose garden before visiting the Eglise Franciscaine (Mon–Sat 10am–noon, 3–5.30pm; free). Although the church facade has been rebuilt in a rather garish style, the interior is a simple Gothic structure with walls and vault entirely covered in murals, and a Baroque retable. The church contains three paintings by local master Ludovico Bréa (for more information, click here): a Pièta triptych from around 1475, a Crucifixion of 1512 and a late Deposition attributed to Bréa, dating from around 1520. It is interesting to contrast the Gothic emotion depicted in the early angular Pièta with the luminosity and symmetrical layout of the later Crucifixion, with its solidly posed figures and perspective that carries to a far-off landscape.

Upstairs, the monastic buildings contain a small museum presenting the history of the Franciscan order in Nice, through paintings, manuscripts, a reconstituted monk’s cell and a small, simple chapel.

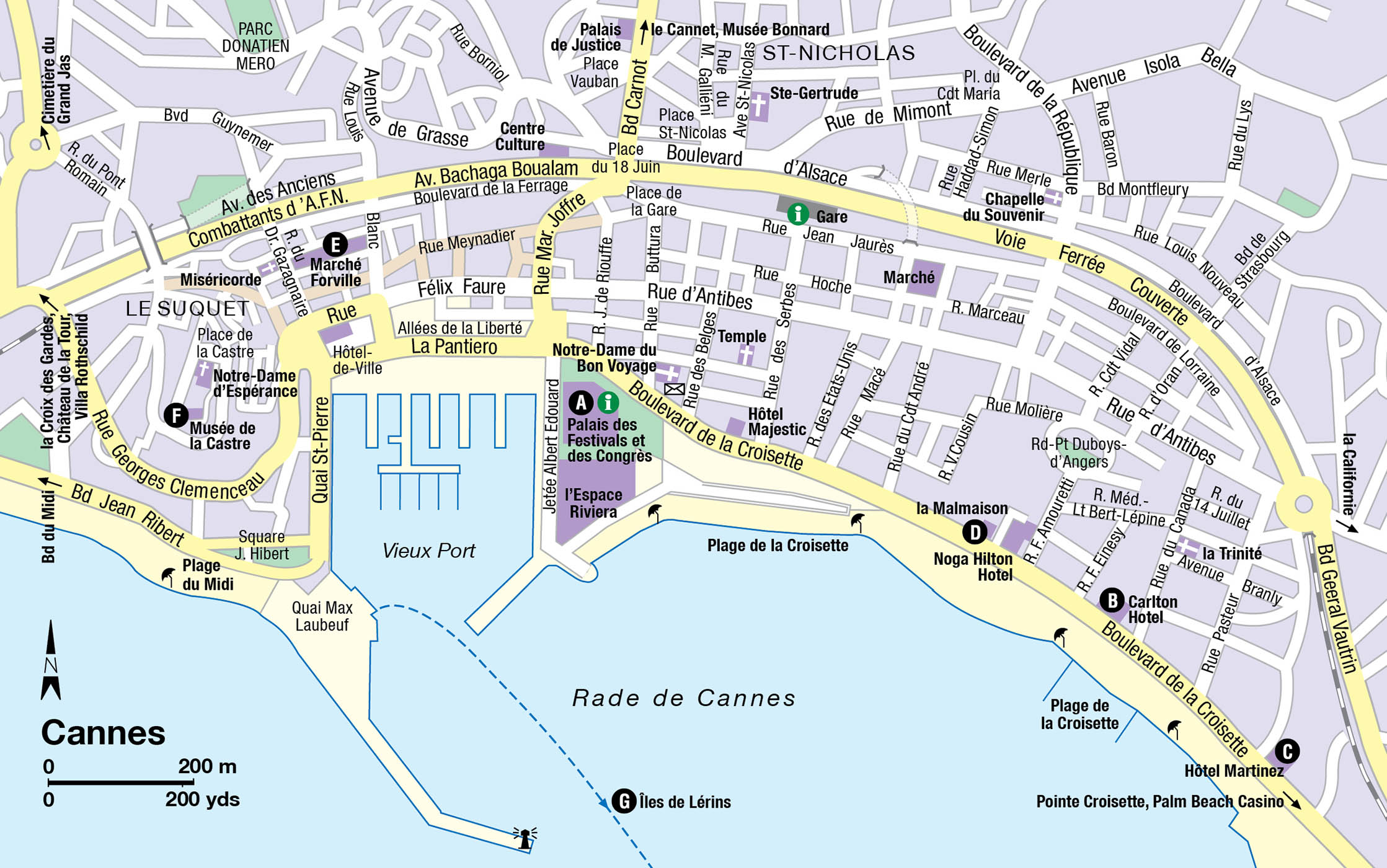

CANNES

Cannes 2 [map] is the glamour capital of the Alpes-Maritimes, a place for hedonists to succumb to the indulgence of sun, sand, shopping and more shopping. Yet unlike many Riviera resorts, it does qualify as a real town with an all-year population where, alongside some of the glitziest shops in the world, the Old Town still has the allure of a Provençal village, and men play boules under the trees in front of the town hall.

By far the most scenic way to arrive in Cannes is from the west along the Corniche de l’Estérel, although traffic is often nose to tail during the holiday season. If you are approaching from the autoroute, the road descends to the coast from Le Cannet by boulevard Carnot, past modern apartment blocks and some fine Belle Epoque buildings, including the Palais de Justice and the Hôtel Cavendish, to arrive at the Palais des Festivals.

Sitting on the seafront between the Old Port and La Croisette, the Palais des Festivals A [map] (www.palaisdesfestivals.com) is the symbol of film festival glamour. Although the building itself is an entirely uninspiring piece of 1980s architecture, nicknamed ‘the bunker’, it is part of the Cannes Festival myth, as epitomised by the famous walk up les marches – the steps leading to the grand auditorium – and the trail of handprints made by film stars and directors in the terracotta pavement outside. With its 18 auditoria, however, the Palais is used for numerous events – music industry awards, advertising and property development fairs, luxury shopping and tourism conventions, rock concerts and chess tournaments. The building also contains the Casino Croisette, the tourist office and the Rotonde de Lérins extension overlooking the sea.

Cannes Film Festival

For 10 days in May, Cannes becomes capital of world cinema. Couturiers lend actresses their most extravagant creations, paparazzi snap cast and directors climbing les marches of the Palais des Festivals, fans press behind the barriers in hope of a signature, 4,000 journalists try to get slots in the interview room and Paris’s trendiest nightclubs decamp south. Launched in the 1930s, when the Venice Film Festival was tainted by Fascism, Cannes was chosen for its sunny location and its promise to build a special auditorium. In the event, war broke out and the first festival was held in 1946 in the municipal casino. Over the years, the festival has spawned the International Critics’ Week and Directors’ Fortnight, as well as the vast film market dealings that go on around the port. Although a strictly professional event, the organisers have made some concessions to the public with the Cinéma de la Plage open-air screenings.

The festival sticks determinedly to its art-movie reputation. Directors like Ken Loach and the Belgian Dardenne brothers are regulars; big-budget Hollywood blockbusters tend to be screened out of competition, and the selection remains wildly international – films from Mexico, Iran and Romania all get a look in. There are occasionally some heartwarming surprises – in 2008 the Palme d’Or went to Laurent Cantet’s The Class, acted by a cast of Paris schoolkids (www.festival-cannes.fr).

The festival action unfolds at the Palais des Festivals

iStock

La Croisette

Running east along the bay from the Palais, La Croisette, Cannes’s palm tree-lined seafront promenade, marked the resort’s social ascension in the early 20th century with a trio of legendary palace hotels: the Majestic, opened in 1926, the ornate Carlton B [map], opened in 1912, with two cupolas, supposedly modelled on the breasts of celebrated courtesan La Belle Otero, and the Art Deco Martinez C [map], built by Emmanuel Martinez, who modestly named it after himself. When it opened in 1929, just in time for the transition to the summer season, it was France’s largest hotel, with 476 spacious master bedrooms and 56 for clients’ personal staff.

Taking it easy on La Croisette

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

La Croisette is still a hub of activity, animated by the parade of open-top cars and illuminated at night for an evening promenade. In summer, the long sandy beach is almost entirely taken up by private beach concessions, with restaurants, deckchairs and jetties for parascending and water-skiing, although there is a small, crowded and fuel-fume-polluted public section between the Majestic jetty and the Palais des Festivals.

The first section of La Croisette is home to the smartest designer labels and jewellers, fun for window-shopping even if you’re not in the market for evening gowns and diamond tiaras. Set amid lawns halfway along at No. 47, dwarfed by many of its neighbours, La Malmaison D [map] (Apr–Sept Tue–Fri 10am–12.30pm, 1.30–5.45pm, Sat–Sun until 6.15pm, Oct–Mar Tue–Fri 10am–12.30pm, 1.30–5.15pm, Sat–Sun until 5.45pm; www.musees-nationaux-malmaison.fr) is the last Belle Epoque remnant of the Grand Hôtel, staging a mixed bag of art exhibitions.

Further along, the villas have largely been replaced by apartment buildings, with sun-catching balconies. At the east end, beyond pine-shaded gardens and the Port Canto yachting marina, La Croisette terminates at the Pointe de la Croisette promontory, where the Palm Beach Casino, built in 1929 and reopened in 2002 after several years’ closure, contains a restaurant, gaming rooms, nightclub and an outdoor casino in summer.

Running parallel to La Croisette, rue d’Antibes, which follows the trace of the old royal road between Toulon and Antibes, is almost entirely devoted to the art of shopping, where mainstream fashion chains mix with more cutting-edge stores. Amid the storefronts, if you look up, is some fine late 19th-century architecture, with sculptures and wrought-iron decoration. At night, the block formed by rue des Frères Pradignac, rue du Commandant-André and rue du Dr Gérard-Monod is a focus for nightlife, with its restaurants and lounge bars.

The Port Vieux and Marché Forville

West of the Palais des Festivals is the Port Vieux, reconstructed in the 19th century to meet the demands of its new British visitors. Today, a few surviving fishing boats sit somewhat incongruously among the luxury yachts, surrounded by the colour-washed facades of the quai St-Pierre and brasseries, bars and shellfish restaurants of avenue Félix Faure. Next to the pompous 19th-century town hall, the plane tree-lined Allées de la Liberté contain a vintage bandstand, pétanque pitches and a flower market. In the adjoining square, on a plinth above a very British-looking lion is a statue of Lord Henry Brougham, credited with discovering Cannes for the British after spending a night here in 1834. Nearby, rue du Bivouac Napoléon recalls another visitor, who camped here after landing at Golfe-Juan on 1 March 1815, when he escaped from exile on Elba.

Behind the port, pedestrianised rue Meynadier is lined with inexpensive clothes and shoe stores at one end, simple restaurants, bars and food shops at the other, while a street back, Marché Forville E [map] (Tue–Sun 7am–1pm) covered market provides a taste of the ‘real Cannes’ – though you have to arrive early to find what’s left of the local catch: sardines, tiny sea bream and little rockfish. In summer, stalls are a tempting feast of tomatoes, courgettes, small aubergines, hot little red peppers, melons, peaches and green figs.

Chillies for sale at the Marché Forville

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Le Suquet

Before the arrival of the British in the 19th century, Le Suquet was pretty much all there was of Cannes: a few picturesque streets and stepped alleyways of tall yellow-and-pink houses winding up the hill around the fortress constructed by the monks of Lérins. Quiet and villagey by day, Le Suquet is particularly lively at night, when visitors flock to the bars and restaurants on rue St-Antoine and its continuation, rue du Suquet. At the top, beyond the 16th-century church of Notre-Dame de l’Espérance, whose parvis is used for open-air concerts in summer, shady place de la Castre offers a fine view from the ramparts. Entered through a pretty garden, the cool, whitewashed rooms of the former castle now contain the Musée de la Castre F [map] (July–Aug daily 10am–7pm, Apr–June, Sept Tue–Sun 10am–1pm, 2–6pm, Oct–Mar Tue–Sun 10am–1pm, 2–5pm), a surprising ethnographic collection donated by the Dutch Baron Lycklama in 1877. An eclectic array of masks, headdresses, statues and ceremonial daggers from Tibet, Nepal and Ladakh, bone carvings from Alaska, animal-shaped jugs from Latin America and archaeological finds from ancient Egypt, Cyprus and Mesopotamia are complemented by a couple of rooms of paintings by Orientalist and Provençal painters. From the courtyard you can climb 109 narrow steps up the 11th-century Tour du Suquet for panoramic views over the town, port and bay.

Steep side street in Le Suquet

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

La Croix des Gardes

West of the port, the Plage du Midi, with the railway running along the side, is less chic than La Croisette, but its largely public beach makes it a better bet if you’re not going to one of the private establishments. Back on the other side of the railway, La Croix des Gardes district is where many British settlers built their residences in a variety of styles ranging from Palladian villas to rustic cottages and crenellated castles, following on from Lord Brougham, whose neoclassical Villa Eléonore stands on avenue du Docteur-Picaud. Most are now private apartments only glimpsed from the road amid luxuriant gardens, but you can see the Château de la Tour on avenue Font de Veyre (now a hotel, for more information, click here) and the Villa Rothschild (1 avenue Jean de Noailles), built in 1881 for the Baronne de Rothschild, and now the municipal library, whose gardens planted with palms, catalpas and other exotic species have become a pleasant public park. At the top of the hill, boulevard Leader and avenue de Noailles emerge in a surprisingly wild protected nature area, crossed by several footpaths, and marked at the top by a glistening steel cross.

Prosper Mérimée (1803–70), novelist and inspector of historic monuments, was another winter visitor, staying with English sisters Emma and Fanny Lagdon. He preferred Cannes to Nice, which he thought as crowded as Paris, but detested many of the new buildings (see box). He is buried alongside many British settlers, including Lord Brougham, and numerous Russian aristocrats and artists, in the Cimetière du Grand Jas, which descends in scenic terraces down the eastern flank of the hill.

Mérimée’s verdict

‘The English who have built here deserve to be impaled for the architecture they have brought into this beautiful country. You cannot imagine how distressed I am to see these stage-set castles posed on these lovely hills.’

Le Cannet

Reached up boulevard Carnot, on the hill above Cannes, the suburb of Le Cannet was originally settled by Italian immigrants brought here by the monks of Lérins in the 16th century to cultivate the olive groves. The old centre, focused on rue St-Sauveur and place Bellevue, still has the air of a little Provençal hill village with narrow streets and a belfry with a wrought-iron campanile. Le Cannet is particularly associated with painter Pierre Bonnard, who bought a house here in 1926; staying largely remote from the social whirl of the coast below, he painted the village rooftops, the view from his window, with patches of yellow mimosa, or his beloved wife Marthe. Next to the town hall the Hôtel Saint-Vianney has been turned into the Musée Bonnard (Apr–Oct Tue–Sun 10am–8pm, Thur until 9pm, Nov–Mar Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; www.museebonnard.fr).

An ethereal mural in Le Cannet

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

La Californie

Later arrivals often built their villas on the hills of La Californie and Super-Cannes on the eastern side of town, still the most exclusive area to live, though fences and security gates mean that few are visible from the street. Two that can be visited are the Chapelle Bellini (Parc Fiorentina, 67 bis avenue de Vallauris; Mon–Fri 2–5pm; free), an Italianate chapel built in 1884 that was more recently the studio of painter Emmanuel Bellini, and the Villa Domergue (15 avenue Fiesole; July–Sept daily 11am–7pm), the house and terraced Tuscan-style gardens designed in 1934 by society portrait painter Jean-Gabriel Domergue. After a successful career as a graphic artist for the fashion houses, Domergue, who had been taught by Toulouse-Lautrec and Degas, moved south in the 1920s, where he organised big parties, designed posters and churned out countless languid portraits of women, including Brigitte Bardot and Nadine de Rothschild. There are paintings and sculptures by Domergue and his wife around the house and garden, and the villa is used for temporary exhibitions and outdoor jazz concerts in summer. Lower down towards the sea, the neo-Gothic Eglise Saint-Georges (27 avenue Roi Albert) was built in 1887 in memory of Queen Victoria’s youngest son, Prince Leopold, who died here in 1884. This was also the area favoured by the Russian aristocracy, as witnessed by the starry blue onion dome of the Eglise Orthodoxe Russe Saint-Michel-Archange (impasse des Deux-Eglises, 40 boulevard Alexandre III; Sat 5–6pm).

The Iles de Lérins

A 10-minute boat ride from the Port Vieux, the Iles de Lérins G [map] seem a world apart from La Croisette: yet for much of its history the little fishing settlement of Cannes was merely a dependence of the monastery on Ile Saint-Honorat and the islands were frequently a prized trophy in European wars.

The nature reserve on Ile Sainte-Marguerite

Shutterstock

Ile Sainte-Marguerite

The larger of the two islands, Sainte-Marguerite is perfect for walks and picnics, and despite numerous ferries a day in summer it’s still possible to get away from the crowds. There’s a sheltered beach to the west of the harbour, and plenty of smaller rocky creeks to be found along the 8km (5-mile) footpath that circles the island. En route are great views of the Estérel mountain range, Ile Saint-Honorat and the Bay of Cannes. Most of the interior is covered in forest – eucalyptus, holm-oak, aleppo and parasol pines – and traversed by numerous footpaths and picnic sites. A botanical trail points out the most interesting plants, while the Etang du Batéguier, a small brackish lake near the western tip, is a nature reserve drawing a wide variety of birds. Look out also for a couple of fours à boulets – stoves used to heat up cannon balls.

Dominating the cliff on the north side of the island, a short uphill walk from the harbour is the impressive star-shaped, bastioned Royal Fort. It was begun by Cardinal Richelieu, continued by the Spanish who occupied the island from 1635–7 during the Thirty Years War, when it made a convenient point on the way between Spain and Italy, and given its final form by Louis XIV’s brilliant military engineer Vauban. Assorted buildings within the ramparts contain the long gunpowder store, the barracks and a chapel.

The old keep, which was erected in the 17th century around a medieval tower, contains the Musée de la Mer (June–Sept daily 10am–5.45pm, Oct–Mar Tue–Sun 10.30am–1.15pm, 2.15–4.45pm, Apr–May until 5.45pm), which reveals several different eras of the defence of the island. Vaulted Roman cisterns, constructed to store precious water, now contain a maquette of the original Roman castrum, along with fragments of mosaic and a collection of Greek amphorae found from shipwrecks that testify to an ancient wine trade. In the late 17th century, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, it became one of four royal prisons in the Mediterranean where Protestants and others seen to pose a threat to the crown were held without trial. The cells contain a memorial to six Protestant priests held here, as well as a manuscript written by Scottish prisoner Andrew MacDonald, found in a hole in the wall. The room that most stirs the imagination, however, is the cell of the Man in the Iron Mask, where the mysterious figure immortalised by Alexandre Dumas was imprisoned from 1687–98.

Getting there

Several companies run trips from Cannes to the islands all year round, leaving from quai Laubeuf beyond the car park at the western end of the port, but note that you cannot combine both islands in one trip. Boats to Sainte-Marguerite: Horizon, tel: 04 92 98 71 36, www.horizon-lerins.com; Trans Côte d’Azur, tel: 04 92 98 71 30, www.trans-cote-azur.com; to Saint-Honorat: Planaria, tel: 04 92 98 71 38, www.cannes-ilesdelerins.com.

Ile Saint-Honorat

Smaller and wilder than Ile Sainte-Marguerite, Ile Saint-Honorat was for centuries one of the most important religious sites in Europe, home to the powerful monastery founded around 410 by Honoratus and a small group of companions, becoming an important place of pilgrimage. On a flat spit of land jutting out at the southern tip of the island is the severe Monastère-Donjon, which was fortified against pirate raids, with chapels and refectories set around an unusual two-tiered cloister. The remains of seven ancient chapels are dotted around the island, including the 10th-century Chapelle de la Trinité and the unusual octagonal Chapelle Saint-Caprien. During the Revolution, the monastery was confiscated as national goods and sold off to a Parisian actress who used it to host parties. In 1859, the island was acquired by the bishop of Fréjus and a new monastery (daily guided thematic visits; www.abbayedelerins.com) was rebuilt around a medieval cloister, which now houses a small community of Cistercian monks who cultivate the vineyard and produce a plant-based liqueur called Lérina. Dining on the terrace of the island’s only restaurant, La Tonnelle (for more information, click here), offers wonderful views across the coast.

The monastery on Ile Saint-Honorat

iStock

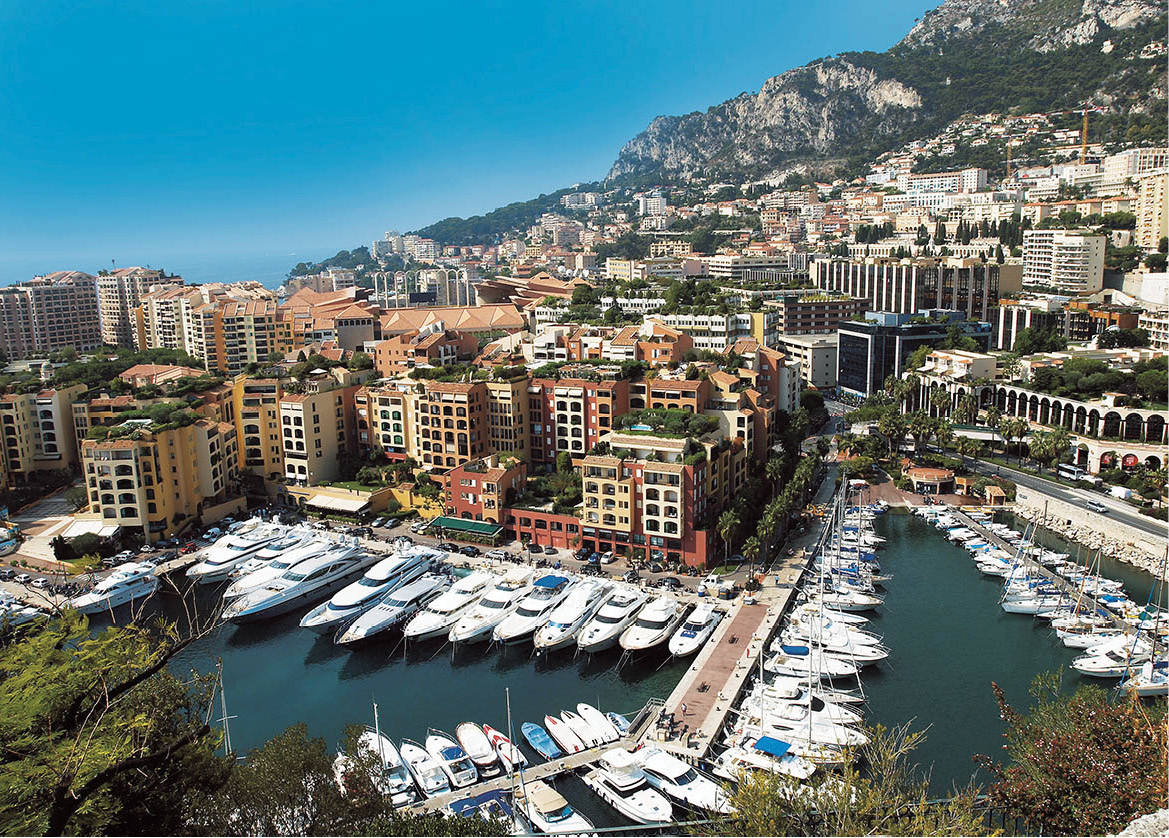

Monaco

The second-smallest state in Europe – after the Vatican – is a tiny autocratic anomaly in the midst of republican France: a surreal place squeezed between sea and mountain, where princes and princesses and the paraphernalia of monarchy exist alongside skyscrapers and international banks that give it the air of a mini Hong Kong; a tax haven for tennis players; and a jet-setters’ playground, where the chief pastime is driving Ferraris around the hairpin bends. The Riviera’s land pressure is at its greatest here, and Belle Epoque villas are dwarfed by apartment blocks, all straining for a sea view. Monaco divides into several distinct districts: Monte Carlo around the Casino, plus its eastward beach extension Larvotto; La Condamine around the Port Hercule; Monaco-Ville, the original town up on its rock, also known as Le Rocher; Fontvieille, on reclaimed land on the western side; and Moneghetti, inland on top of the hill. It may be just 2km (1.2 miles) square, but a one-way system and lots of tunnels make navigation complicated. Leave the car in a car park and use taxis, the efficient bus service, or go by foot – a useful system of lifts and stairways helps pedestrians to negotiate the steep hills.

Luxury yachts compete for attention in Fontvieille harbour

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo 3 [map] is the district that for most people epitomises Monaco, centred around the hub of place du Casino. The neatly manicured lawns and fountains of the Jardin des Boulengrins, which descend from boulevard des Moulins, make a splendid approach to the Casino de Monte Carlo A [map] (daily 2pm–late; over 18s, ID required, smart attire; group tours 9am–noon; www.casinomontecarlo.com) with its sculptures on the facade, green copper roof and twin turrets. It is hard to imagine that this was simply an olive-tree-covered hill until the 1860s, when Prince Charles III, in search of a new source of revenue following the cession of Menton and Roquebrune to France, had the bright idea of opening a casino. After an unenthusiastic start, the prince awarded the concession to run it to François Blanc, founder of the Société des Bains de Monaco (SBM). This company (its main shareholder is now the State of Monaco) still runs the majority of Monte Carlo’s finest hotels, restaurants, casinos, spas, sporting facilities and nightclubs.

As seen on screen

The Casino de Monte Carlo is a favourite movie location. It features in Hitchcock’s Rebecca and his Riviera romp To Catch a Thief, with Grace Kelly and Cary Grant, in Jacques Demy’s La Baie des Anges and Victor Saville’s 24 Hours of a Woman’s Life. Another casino habitué is James Bond, who tries his luck in both GoldenEye and Never Say Never Again.

By day, tourists crowd round to take photos; by night, this is still the most glamorous of Monaco’s numerous gambling establishments, where roulette and blackjack are played against a backdrop of allegorical paintings and chandeliers. There’s a separate entrance for the salons privés, reserved for high-staking players. In 1878, Blanc’s widow Marie called in architect Charles Garnier, who had recently designed the Paris Opera, to add an opera house to encourage gamblers to stay in town a little longer. The Salle Garnier was inaugurated in January 1879, tacked on the back of the casino. Over the years the opera has welcomed renowned singers, from Adelina Patty, Nelly Melba and Russian Schaliapine to Plácido Domingo, as well as becoming home to Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The auditorium is a gorgeous confection, painstakingly restored in 2005 right down to five different shades of gold leaf. Opera and casino share the same foyer, giving a unique opportunity for a flutter in the interval.

Around the Casino

On one side of the casino, historic brasserie Café de Paris has a superb terrace for watching the comings and goings on the square; inside, slot machines are busy all day long, while the renovated gaming tables have a Formula 1 theme. Across the square, Rolls-Royces and Ferraris line up outside the Hôtel de Paris B [map], built by the SBM in 1864, the first and still grandest of the grand hotels houses the Louis XV restaurant and the Bar Américain. In the splendid lobby, the horse’s knee on the equestrian statue of Louis XIV has been polished gold by superstitious gamblers hoping for good luck.

Café de Paris on place du Casino

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

This is also Monaco’s smartest shopping territory, with jewellers and designer labels lining avenue des Beaux-Arts and place Beaumarchais between the Hôtel de Paris and the huge Belle Epoque Hôtel Hermitage (which now has a putting green on the roof).

Below the Casino gardens, a lift and stairs descend to the roof terraces of the huge Spélugues complex (the original name of the district before Prince Charles renamed it after himself) built in 1978. Constructed like a series of overlapping hexagons jutting out on concrete stilts into the water over a roaring road tunnel, it comprises the 616-room Fairmont Hotel, apartments and the Auditorium Rainier III congress centre, which has a mosaic on the roof by Op artist Victor Vasarely.

Further East

In a garden on avenue Princesse Grace, the peach-and-cream stucco Villa Sauber is one of two villas (the other is Villa Paloma in Meneghetti, for more information, click here) that are the home of the Nouveau Musée National Monaco (NMNM; June–Sept 11am–7pm, Oct–May 8am–6pm; www.nmnm.mc). The museum aims to showcase the principality’s cultural heritage in a contemporary manner and the changing exhibitions at Villa Sauber focus on the ‘art of theatre’ or set design. Installation artist, Bertrand Lavier is exhibiting 308 GTS in the museum’s renovated garage.

Over the street, the Jardins Japonais C [map] (daily 9am–sunset; free) on the quayside provides a touch of oriental Zen calm, with streams traversed by stepping stones and Japanese bridges, Shinto shrines, raked gravel and trees trimmed into sculptural forms. Behind it, the polygonal glass-and-copper structure overlooking the sea is just the tip of the iceberg that is Grimaldi Forum (ticket office Tue–Sat noon–7pm; www.grimaldiforum.com): a huge, partially buried venue for art exhibitions, congresses, concerts and occasional ballet and opera productions, as well as the super-stylish restaurants Zelo’s (for more information, click here) and Café Llorca (for more information, click here).

Beyond here Monaco’s man-made Larvotto Beach is mostly public, with coarse imported sand and a couple of restaurants, bordered to the east by the Méridien Beach Plaza and the Sporting Club d’Eté, opened in the 1970s, home to restaurants and Monaco’s most famous nightclub, Jimmy’z.

Monaco Grand Prix

Held around the narrow streets of Monte Carlo and La Condamine, the Monaco Grand Prix is considered the slowest but most difficult of the Formula 1 races, with its notorious chicane bends, changes of level and road-tunnel exit. The first race was organised on 14 April 1929 by the Automobile Club de Monaco and won by a certain William Grover-Williams in a green Bugatti, and it became part of the new Formula 1 season in the 1950s. Since then Ayrton Senna won it six times, Graham Hill and Michael Schumacher five times each. People reserve tickets for the grandstands along the Port Hercule or in race-side hotels, restaurants and apartment roof terraces months, even years, ahead, champagne lunches included, or watch from private yachts in the harbour. Once the grandstands and barriers have been dismantled, the roads are returned to the Bentleys, Ferraris and Lamborghinis that generally occupy them, though various companies offer tourists the chance of experiencing at least a semblance of the thrills in a red Ferrari.

Monaco’s man-made Larvotto Beach

iStock

La Condamine

The natural deep-water harbour of the Port Hercule D [map] has been used ever since the Greek Phocaean trading post of Monoikos. Today the port is one of the prime spots for the Formula 1 Grand Prix, when grandstands are set up along quai Albert I. The rest of the year, with its large outdoor swimming pool (transformed into an ice rink in winter) and pizzerias, it is used for all sorts of events, ranging from international showjumping in June to a water splash and funfair in August. Quai Antoine I is home to the ever-fashionable American restaurant Stars ’n’ Bars (for more information, click here), while the spectacle of swanky yachts with multi-storey decks and uniformed crews makes quai des Etats-Unis a favourite promenade. The port has grown since 2000, with the construction of a counter-jetty, designed to keep out easterly winds and welcome in the yachts of the ultra-rich, and a massive semi-floating concrete dyke towed across from Spain to accommodate vast cruise ships.

Alongside the port, now squeezed under a flyover, the Eglise Sainte-Dévote (daily 8.30am–6pm) is dedicated to the principality’s patron saint, Corsican Saint Devota, who is said to have drifted ashore here in the 4th century. The church, begun in the 11th century, was almost entirely reconstructed in the 19th. A boat is burnt on the cobbled square in front each 26 January on the eve of the saint’s feast.

Inland, mainly low-rise La Condamine is about as close as Monaco gets to everyday living, with a few Belle Epoque terraces and the lively restaurant-lined rue Princesse Caroline. Under the shadow of Le Rocher, arcaded place d’Armes is home to a covered food market (mornings daily) with quirky bars and stalls inside selling meat, patisseries and pasta – each with a photo of the current prince proudly on display – and fruit and vegetable stalls outside on the square.

Monaco-Ville

Sitting on top of its rock, Le Rocher or Monaco-Ville is dominated by the picturebook Palais Princier on place du Palais, still the royal residence, ruled – apart from a few interludes – by the Grimaldi family ever since François Grimaldi sneaked in disguised as a monk in 1297. Walk up from place d’Armes or take one of the frequent buses, which deposit you on place de la Visitation, a 10-minute walk from place du Palais. The square lined with cannons and pyramids of cannon balls provides great views from the ramparts on each side. Each day, the changing of the guard takes place promptly at 11.55am, accompanied by much marching and drum-beating.

Palais Princier

iStock

The Palais Princier E [map] (daily Apr–Oct 10am–6pm; www.palais.mc) was constructed around the fortress begun by the Genoans in the 13th century and embellished during the Renaissance when the frescoed, arcaded Galerie d’Hercule overlooking the Cour d’Honneur was built, with a double horseshoe staircase modelled on Fontainebleau; this inner courtyard was the venue of the wedding ceremony of Prince Albert II and Charlene Wittstock in July 2011. The excellent audio guide (complete with a welcome from the prince) included with the ticket moves through the State Apartments, taking in the mirror gallery, the bright-blue Louis XV room, panelled Mazarin room and the bedroom where Edward Augustus, duke of York and brother of George III, died in 1767 after falling ill en route for Genoa; and finishes in the Throne Room, with a fireplace in La Turbie marble and a canopied Empire-style throne where Prince Albert II was crowned in 2005, all accompanied by a large number of royal portraits.

Exploring the Old Town

The Old Town’s handful of narrow streets of pastel-coloured houses, now largely taken up by souvenir shops, make an intriguingly folksy contrast to Monte Carlo. Bypassed by most visitors is the Chapelle de la Miséricorde F [map] (daily 10am–6pm; free) with striped marble walls, white marble sculptures and a painted wooden sculpture of the Dead Christ attributed to Monaco-born François-Joseph Bosio (1768–1845), which is paraded through the town on Good Friday. Also worth visiting is the pretty 17th-century Chapelle de la Visitation G [map] (Tue–Sun 10am–4pm), which provides an appropriate setting for a fine private collection of Baroque religious art that includes paintings of saints Peter and Paul by Rubens, works by Ribera and Zurbarán, and a set of Spanish grisaille paintings.

Cathedral and Aquarium

The Cathédrale H [map] (daily May–Sept 8am–7pm, Oct–Apr 8.30am–6pm, closed during services) was built in 1875 and is a severe neo-Romanesque affair, with flags along the nave and a Byzantine-style mosaic over the altar, made by the same craftsmen who worked on the Casino. In the side chapels are reliquaries of Saint Devota, Monaco’s patron saint, and of Roman legionary Saint Roman, and an altarpiece by Ludovico Bréa showing St Nicolas surrounded by saints, among them Saint Devota. The simple slab-like tombs of the princes of Monaco are set into the ground around the apse, drawing visitors and pilgrims especially to those of Princess Grace, who was laid to rest in 1982, and Prince Rainier, who joined her here in 2005.

Monaco-Ville’s neo-Romanesque cathedral

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

In an imposing white building that descends down the cliff face from avenue St-Martin, the extremely popular Musée Océanographique et Aquarium I [map] (Apr–June and Sept daily 10am–7pm, July–Aug 9.30am–8pm, Oct–Mar 10am–6pm; www.oceano.mc) was founded in 1910 by sea-faring Prince Albert I, ‘the scientist prince’, who trained in the French navy before setting off on countless oceanographic expeditions, mostly to the Arctic. The upstairs museum is an elegant time-warp tribute to his voyages, with its wooden cases, whale skeletons, navigation charts, and glass jars containing preserved specimens. The chief attraction is the downstairs aquarium, where cleverly lit tanks, fed by water pumped in directly from the sea, include a shark lagoon and living coral reefs populated by brightly coloured species from the Mediterranean and tropical oceans.

Coral reef at the Aquarium

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

In the gardens that descend below avenue de la Porte Neuve, the ruined 18th-century Fort Saint-Antoine on the headland is now an amphitheatre used in summer for outdoor performances, while lower down by the Parking des Pêcheurs car park is the Cinéma d’Eté, where recently released movies are screened outdoors in the summer months.

Fontvieille

This entire new district, created on 25 hectares (60 acres) of land reclaimed from the sea, was one of the pharaonic projects of the 1960s that earned Rainier III the label ‘the builder prince’ – a vast complex of bland apartment blocks in neo-Provençal tones around a yachting marina, with a number of bars and brasseries popular with international expats. West of the marina bordering Cap d’Ail lie the heliport, the Stade Louis II (3 avenue des Castelans), home to Monaco football club, which plays in the French premier league, along with an athletics track and an Olympic-size swimming pool; the Espace Châpiteau, a permanent big top used for the prestigious circus festival each January; and the Princesse Grace rose garden (daily 8am–sunset; free), where 4,000 rose bushes have been planted in a heart-shaped design, in memory of the princess who died under what are still mysterious circumstances in a car accident on the Corniche in 1982.

Homage to Grace

The parcours Princesse Grace is a trail of 25 places in the principality that are associated with the former Hollywood film star Grace Kelly, who married Prince Rainier III in 1956. Sites are marked by panels with black-and-white press photos of the princess carrying out royal functions.

Along the parcours Princesse Grace

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

Local people, however, come to Fontvieille for the shopping centre, with a large Carrefour hypermarket. From here, escalators climb to Terrasses de Fontvieille, a rather bizarre setting for a cluster of small museums.

A Trio of Museums

The Musée des Timbres et des Monnaies (daily July–Aug 9.30am–6pm, Sept–June 9.30am–5pm), with a stamp shop on site, is devoted to Monaco stamps (since 1885) and coins (since 1641), which are popular with philatelists and numismatists. The Musée Naval (daily 10am–6pm; www.musee-naval.mc) houses ship models tracing maritime history.

Not surprisingly in motor-racing-crazy Monaco, the most substantial member of the group is the Collection de Voitures Anciennes de SAS le Prince de Monaco J [map] (daily 10am–6pm; www.palais.mc), the collection of vintage cars amassed by Prince Rainier III. They range from a Dion Bouton made in 1903 and an early Panhard et Levassor from 1907 via lots of vintage Rolls-Royces and Princess Grace’s humbler Renault Floride to modern racing cars, including Nigel Mansell’s Formula 1 Ferrari, as well as some utilitarian vehicles from the Monaco fire brigade and some early horse-drawn carriages. A recent addition is a prototype racing car ALA50 manufactured in Monaco by Monte Carlo Automobile and given to Prince Albert II for his 50th birthday in 2008.

To the side of the museum is a small zoo, the Jardin Animalier K [map] (daily June–Sept 9am–noon, 2–7pm, Oct–Feb 10am–noon, 2–5pm, Mar–May 10am–noon, 2–6pm), founded by Prince Rainier. Among its creatures are rhesus monkeys, a hippo, pythons, a rare white tiger and exotic birds.

A vintage Monaco stamp

Shutterstock

Moneghetti

Monaco’s last attraction on the way out of town towards Nice is probably its best. The Jardin Exotique L [map] (62 boulevard du Jardin Exotique; daily Jan and Nov–Dec 9am–5pm, Feb–Apr and Oct 9am–6pm, May–Sept 9am–7pm,; www.jardin-exotique.mc), opened in 1933, is a fantasy land of cactuses and succulents, among them giant agaves, whole colonies of grandmother’s pincushions and 11m (36ft) high euphorbes, some of them over a century old, planted in steep terraces and gulleys down the cliff. The entrance ticket also includes the Grotte de l’Observatoire (guided visits only) at the foot of the garden, a deep limestone cave full of stalactites and stalagmites, and the rather dry Musée d’Anthropologie Préhistorique, displaying archaeological finds, mainly from the Grimaldi caves just across the Italian border.

The Jardin Exotique provides panoramic views over Monaco

Sylvaine Poitau/APA Publications

The 1920s Villa Paloma, perched on a hillside nearby overlooking the harbour, is one of two homes (the other is Villa Sauber, for more information, click here) of the Nouveau Musée National de Monaco (www.nmnm.mc). Here, the changing exhibitions all have the theme of ‘art and landscape’; equally beguiling are the villa’s architectural attributes including stunning stained glass windows.

Excursions

Cagnes-sur-Mer

Just 13km (8 miles) west of Nice, Cagnes-sur-Mer 4 [map] is a popular excursion for the Niçois for a meal out in the medieval hill village of Haut-de-Cagnes, Renoir’s house at Les Collettes, the Hippodrome racecourse and a 3.5km (2-mile) shingle beach. At the top of picturesque Haut-de-Cagnes, with its steep, winding streets of creeper-covered houses, many now containing restaurants and galleries, is the Château-Musée Grimaldi (Wed–Mon July–Aug 10am–1pm, 2–6pm, Apr–June and Sept 10am–noon, 2–6pm, Oct–Mar until 5pm). This was a watchtower constructed by one of the branches of the Grimaldi family, before being converted into a sumptuous Renaissance residence. A galleried, vaulted loggia leads to a magnificent ceremonial chamber, with carved fireplace and dramatic 1620 trompe l’œil ceiling with the Fall of Phaethon, attributed to Genoese painter Giulio Benso Pietra.

The château also contains a small display devoted to the olive tree, the municipal art collection and the surprising Collection Suzy Solidor, donated by the Montparnasse cabaret singer, a former resident of the château, who was painted by many of the successful portraitists of the 1920s. This gives the unusual opportunity of seeing the same person depicted by Kisling, Foujita, Van Dongen, Cocteau and Tamara de Lempicka.

Matisse’s Chapel in Vence

During World War II the elderly Matisse retreated to Vence (14km/9 miles from Cagnes-sur-Mer) to avoid the bombing, renting Villa Le Rêve, where young Monique Bourgeois (later Sister Jacques Marie) nursed and sat for him. In gratitude he offered to decorate the Chapelle du Rosaire for the Dominican order, and ended up designing everything from the building itself with its blue-and-white glazed pantiles to the priest’s cope and the gilded crucifix that stands on the altar. The Chapelle du Rosaire-Henri Matisse (avenue Henri Matisse; Mon, Wed, Sat 2–5.30pm, Tue, Thur also 10–11.30am, closed mid-Nov–mid-Dec) is a meeting of Matisse’s mastery of line in the pared-back drawings of St Dominic, the Virgin and Child and Stations of the Cross in black on white tiles, and of colour in the stained glass, whose reflections send dapples of blue, yellow and green across the walls. Too ill to attend the opening ceremony, Matisse nonetheless sent along a text: ‘This work took four years of assiduous work and is the summary of all my active life. I consider it, despite all its imperfections, as my masterpiece.’

Chapelle du Rosaire Henri-Matisse

Getty Images

The Musée Renoir

Down the hill, east of the modern centre of Cagnes-sur-Mer, the Domaine Les Collettes, now the Musée Renoir (Wed–Mon June–Sept 10am–noon, 2–6pm, Oct–Mar 10am–noon, 2–5pm, Apr–May until 6pm), was bought by the elderly Renoir in 1908. Although now surrounded by urban sprawl and apartment blocks that have partly obscured the view, the house and gardens have changed little since Renoir lived here, receiving visitors such as Pierre Bonnard and Matisse, who painted the garden, as well as photographer Willy Maywald, whose photos hang on the stairs.

Paintings around the house include a study for the large Late Bathers, its heightened, almost garish, palette no doubt something to do with the Riviera’s bright sunshine, which Renoir described as ‘maddening’; and a charming small portrait of his youngest son Claude, Coco Reading, dressed in a sailor suit that can still be seen hanging in the studio. But Renoir, almost crippled by arthritis, increasingly turned to sculpture, producing small bronzes in collaboration with his assistant Richard Guino (who is credited as co-author) and later with Louis Morel.

Mougins

Just 8km (5 miles) inland from Cannes, the chic little hill village of Mougins 5 [map] is a lively gastronomic night out from Cannes, with some of the best restaurants in the region. On the main square, place Lamy, art galleries, craft shops and a clutter of gourmet bistros surround a fountain with a rusty statue of 19th-century explorer Général Lamy, who was born here. Above here pristine stepped ruelles wind up to the much-altered Romanesque church with its wrought-iron campanile. Round the corner by the Porte Sarrazine, a fortified 15th-century gateway, the Musée de la Photographie (Tue–Sun mid-Sept–mid-June 10am–12.30pm and 2–6pm, mid-June–mid-Sept until 7pm; free) has a collection of early cameras and a fascinating array of portraits of Picasso, a former resident of Mougins, by Doisneau, Lartigue, Clergue, Villers and others.

Each September, the village hosts a must-visit event for foodies, Les Etoiles de Mougins (www.lesetoilesdemougins.com), when some of the world’s best chefs gather to demonstrate their skills and inventions.

Dwelling in the attractive village of Mougins

iStock

The Estérel