INTRODUCTION

TRANSFORMATIONS OF VISION

The dry garden of Ryōan-ji in Kyoto is one of the most analysed and photographed works of art in the world. Thus, well before my first visit in November 2006, I felt I knew the garden intimately, and was thoroughly prepared to elaborate on the knowledge I had attained from dozens of books and hundreds if not thousands of images. As soon as I stepped onto the veranda of the temple overlooking the garden, I was stupefied, first by its sublime beauty and soon afterwards by the fact that it hardly corresponded to any description I had read of it. How could this be? Could all previous commentators have been so wrong? Could I have been so blinded by my own prejudices and paradigms? Could I have fallen into the textual trap of confusing image and description for the garden itself? Certainly my attraction to Japanese dry gardens stems from the fact that they corroborate my aesthetic principles, wishes and utopias. But might this passion, hitherto untested against its objects, have falsified my vision? I immediately suspected that my disorientation went far beyond mere culture shock. With each discovery about Japanese culture, my bewilderment seemed to multiply even as my knowledge expanded, and I seemed further from aesthetic enlightenment than ever, as Ryōan-ji led me to consider other art forms and other viewpoints: the stones had their antecedents in Chinese and Japanese painting; the surrounding walls evoked unglazed pottery surfaces; the stone borders hinted at the complicated issues of inside and outside in Japanese architecture; the sparse moss suggested the need for water in an otherwise dry garden, thus pointing to the essential role of atmospheric effects in Japanese art; the raked gravel stressed the role of stylization and stereotype in image and word; and the overhanging cherry tree evoked the crucial interpenetration of art and world. I was to discover that these correspondences were not mere free associations, but are deeply ingrained in Japanese aesthetics. After nearly two decades of meditation on Western gardens and landscape from the Baroque through the modern and postmodern eras, I realized that I had to reorient my ways of seeing completely in order to be able to elucidate my initial astonishment before Ryōan-ji.1

As a result I offer here a certain number of principles, composed in the form of a ‘Manifesto for the Future of Landscape’, to give a sense of my attitudes and hopes – often against the grain of contemporary theory and practice – regarding landscape creation, appreciation and conservation.

1. The garden is a symbolic form, which suggests that symbols are as important as images to guide appreciation as well as restoration. The garden is earthly, but it also reaches to the heavens, and occasionally to the underworld.

2. The garden is never merely a picture, and the ground plan is usually misleading. The spatiality of gardens is plastic and dynamic, such that kinetics is of the essence. The garden is thus a synaesthetic matrix.

3. The garden is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a web of correspondences, a site that should encompass all the arts. Consequently, every garden must be continuously reinvented as a scene for contemporary activities.

4. The garden is simultaneously a hermetic space and an object in the world. Thus the ‘formal’ garden must remain open to the ‘informality’ of nature. Garden closure is a sociological and psychological phenomenon, not an ontological one.

5. The garden is a paradox, necessitating that complexity and contradiction should not be avoided, since the finest metaphors are often unstable and equivocal.

6. The garden is a narrative, a transformer of narratives, and a generator of narratives, such that a garden is all that it evokes. Consequently, tales and symbols are an integral part of gardens.

7. The unpeopled garden is either an abstraction or a ruin, suggesting that all aesthetic value has a use value that must be respected. The most complex landscape is the one most closely observed.

8. The garden is a memory theatre, which must bear vestiges of its sedimented history, including traces of the catastrophes that it has suffered. In the history of landscape, accidents are not contingent, but essential.

9. The garden is a hyperbolically ephemeral structure. Anachronism is of the essence, since a garden is all that it was and all that it shall become.

Ryōan-ji, snowstorm of 31 December 2010.

This summation is offered as a touchstone for the investigations that follow, not so much as a corrective to my initial perplexity before Ryōan-ji, but as a spur to new intuitions and as a conceptual guide to the seemingly disparate, but in fact crucial, relations between gardens and the other arts, notably ceramics and cuisine. If there is a constant across these pages, it is the theme of Zen; but this is not the subject of the book, but rather an ineluctable and illuminative thread.2 Ultimately, every artwork bears its own phantasmic ontology, which must be distinguished from the cultural forms and symbols that ground the work. Throughout history and across cultures, the forms of and relations between representation and vision are constantly changing. Our ways of seeing must be no less adaptable, subtle and inventive.

THE FORMAL STAGING of the Japanese aesthetic sensibility is centred on the Zen-inspired tea ceremony, a sort of Gesamtkunstwerk which links painting, calligraphy, pottery, lacquer, woodcraft, architecture, design, poetry, cuisine, flower arranging, gardens and the gestural choreography of the ceremony itself in a highly ritualized event. Here, every art form informs all other art forms, and appreciation is a global experience. As Christine M. E. Guth explains:

The true man of tea is measured by the skill with which he combines articles from his collection so that they form a harmonious ensemble in the tea room. This process, known as tori awase (selecting and matching), requires broad cultural knowledge, connoisseurship, and creativity. The host must consider the context: the season, the occasion, and the identity of the guest or guests. He must take into account the size, shape, texture, color, and material of each work of art . . . Although he must also keep in mind historical connotations such as the origins, history of ownership, and previous use of each article, he must use this knowledge creatively, so as to make each gathering a unique and memorable experience.3

Kōtō-in, a subtemple of Daitoku-ji, tearoom.

Inspired by earlier Chinese Taoist and Buddhist types of tea ceremonies, Japanese forms of tea were first formulated by Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481), developed in the wabi-sabi style by Murata Shukō (1423–1502), elaborated by Takeno Jōō (1502–1555), to be finally systematized in what would become its modern form, still practised today, by Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591). Fundamentally, the tea ceremony is said to be nothing but chanoyu, meaning simply ‘hot water for tea’, a conceit suggesting that this art fundamentally exists not so much in the stylized gestures and the aesthetic disposition of objects, but rather as an ideal of appreciation, a model of connoisseurship, a form of intuition, a source of inspiration. But in fact it is an ultra-sophisticated combination of art appreciation, etiquette and spiritual discipline.

Zen Buddhism came to be at the core of Japanese culture for a number of reasons: the attractiveness to the rising warrior (samurai) class of a religion centred not on scripture and prohibitions but on volition and action; the fact that some Zen monks were widely travelled both within Japan and outside, and were thus a conduit of culture and trade; and that the egalitarian tea aesthetic fostered by the ceremony transformed certain temples into a social melting pot. Monasteries were repositories of art and learning, with many monks themselves being artists, and these temples already had aristocratic backing, and were thus integrated into the power structure. As tea became one of the ceremonial keys to Zen by the sixteenth century, this ceremony may be seen as a condensation of Japanese aesthetics, indeed as its predominant aesthetic paradigm, to such an extent that it has even been said that the spirit of tea is equivalent to the spirit of Zen. Tea is effectively the aestheticization of Zen, or, as the early tea afficionados used to say, ‘tea and Zen have the same taste’.

In a more complex formulation, one could claim that tea is ritualized and spiritualized utilitarianism in the aura of simulated aestheticized poverty, where, according to Haga Kōshirō, a scholar of Zen and medieval Japanese history, ‘a higher dimension of transcendent beauty is created by the dialectical sublation of an inner richness and complexity into the simple and the unpretentious’.4 Zen has spiritual, material and social manifestations: the spiritual centred on the inner life, where corporeal discipline, ritualistic tasks, prayer, deep meditation and questioning (kōan) all aim towards self-enlightenment; the material concerning the aesthetics of tea, where shared appreciation of beauty guarantees collective harmony; and the social allowing the tea room or hut to serve as a sort of literary salon, where different classes in an otherwise rigidly hierarchical society had the rare opportunity of interacting.5 In its ideal form tea is a spiritual exercise, while in its decadent form it often becomes little more than mannerism and snobbism, a cover for power brokerage and a pretext for art transactions. Though such decadence is not unexpected at certain historic junctures, it is nonetheless rather surprising to find accounts of hypercritical fault-finding among even the greatest of tea masters. This is certainly a sign of the difficulty of attaining spiritual heights, through tea or otherwise, and of the ease of sinking into commonplace worldly concerns. Rupert A. Cox stresses the complexities of the opposition between the spiritual and the material at the heart of Zen culture – leading to many ambiguities and paradoxes – by analysing a series of crucial oppositions: religion / art; Buddhist world rejection / Confucian world affirmation; nobody / body; hermit / aesthete; discipline / etiquette; edifying experience / aesthetic form; enlightened / worldly; ascetic / aesthetic; existence / representation; immediacy / mediation; iconoclastic / iconophilic; formless / formal; non-verbal intuition / verbal or visual expression.6 However, for numerous Buddhist schools, these oppositions are not absolute, and it is deemed thoroughly possible, even necessary, to realize enlightenment in both ordinary everyday experience and the arts. As Joseph D. Parker claims, ‘the relation between the realm of enlightenment and nirvana is closely associated and even identified with the samsaric world of form and passionate attachments’ whence, ‘the efficacy of language and other cultural mediums for realizing Buddhist wisdom’.7

Zen stresses self-discipline, profound meditation and enlightenment through intuition by short-circuiting logic, metaphor, imagery, narration. The transcendental insights of Zen are illogical and paradoxical, but this does not negate the possibility of a deep sense of connectedness with objects and nature, nor does it obviate the foregrounding of metaphoric correspondences between all things and the interrelatedness between all arts. This is a form of spirituality without doctrine and scripture, where the bonds of tradition are loosened, or may even be altogether cast off, making Zen a veritable spur to creativity. In a sense, while its spiritual culture strives towards a non-metaphoric grasp of reality, the material culture of Zen offers a web of metaphors. A lifetime would not suffice to explore fully the subtleties of this aesthetic – geared to intuition, not demonstration, and thus immune to discursive proofs – but a consideration of its key terms may suggest how we can achieve a state of mind that would, if not guaranteeing enlightenment (satori), at least heighten our receptivity to Zen-inspired art.

The specialist of Zen culture Hisamatsu Shin’ichi writes of seven characteristics particular to the Zen sensibility: asymmetry, simplicity, austere sublimity or lofty dryness, naturalness, subtle profundity or deep reserve, freedom from attachment, tranquility.8 Donald Keene reduces these to four pertinent features: suggestion, irregularity, simplicity, perishability.9 Such schemas have been criticized for being too static and ahistorical, yet they can easily be amended by adding certain nuances, both formal and historical, that are simultaneously more complex and more direct. It is here that specifically Japanese aesthetic notions complicate the issue, since the forms taken by such consummate beauty proffer particular characteristics. It is often claimed that such terms cannot be translated. Of course, the same may be said for our own notions of ‘art’ and ‘beauty’. The entire history of Western philosophy has attempted to clarify them, and they have only grown more complex as a result of all that study. What is crucial is to grasp the changing and polysemic significance and use value of these terms in their shifting historic context, rather than seeking impossible equivalent translations.

The infinitely complex combination of wabi and sabi, elaborated by Rikyū, and shibui, developed later in the history of tea during the Edo period (1603–1868), together set the proper psychological, spiritual and aesthetic attitude for appreciating Japanese art. The semantic density of these terms, along with their vast range of denotations and connotations, already implies existential richness and philosophical complexity. These terms designate complex aesthetic attitudes, which can be roughly parsed as follows. Wabi suggests the positive values of poverty and its attendant aspects of quietness, tranquillity, solitude, humbleness, frugality, unobtrusiveness, asymmetrical harmony, elegant rusticity. Haga Kōshirō expresses this sensibility by condensing it into three forms of beauty: simple and unpretentious, imperfect and irregular, austere and stark, and D. T. Suzuki refers to a joyful ‘active aesthetic appreciation of poverty’.10 Sabi signifies wear and patination by age and use as well as rust; it is a prime aspect of aesthetic sensibility inscribed in the Japanese language, since the word meaning to improve or to perfect, migaku, also means to polish or to rub. The patina on a bronze or the wear on a tea bowl will increase their value, as well might other sorts of imperfections or damage. Similar effects are also evident in architecture, as in the final coat of plaster that covers the interior of a kura (storehouse), which is traditionally covered with lampblack that is polished first with cloth, then with silk, and finally with the bare hand, to create a surface that appears like black lacquer. Another striking example of such artificially produced sabi is an ancient manner of adding lustre to wooden cabinets by polishing them with cloths dipped in used bath water, so as to rub the sebaceous secretions left in the water into the wood.11 One might say, by analogy, that lichen and moss create the sabi of stone, while clouds constitute the sabi of the moon, and fog that of the mountains, adding to their beauty. Sabi consequently denotes a sense of familiarity, continuity, history, antiquity, and connotes a corresponding sense of passing and loss, loneliness and melancholy. By extrapolation, in its extreme instances, it evokes bleakness, chilliness, dessication, desolation, extinction.12 Shibui, literally meaning astringency,13 directly informs the representational modalities of the arts related to tea, denoting understatement, suggestion, restraint, modesty, discrimination, formality, serenity, quiet taste, refined simplicity, noble austerity. D. T. Suzuki goes so far as to claim that, ‘in some ways, wabi is sabi and sabi is wabi; they are interchangeable terms’, ultimately subsuming the formal into the spiritual, such that wabi, sabi and shibui are inextricably intertwined.14 Beauty in Zen culture signifies an appreciation that spontaneously and intuitively incorporates all that is implied by these three terms. To interiorize these qualities is to approach a state of mind that can appreciate all Zen-inspired traditional Japanese art.15

The tea ceremony, circumscribed by centuries of ritualized gesture and iconographic codification, fundamentally seeks a state of mind guided by wabi-sabi, such that the material culture of Zen offers an allegory of its spiritual culture. That said, there seems to be no systematic correlation between aesthetics and enlightenment.16 Tea is thus simultaneously an appreciation of material culture and a spiritual quest, all at once proffering an aesthetics, an ethics and an epistemology. Tea is both an artistic and a social event, each ceremony being a once-in-a-lifetime gathering – ichigo ichie (one time, one meeting) – seeking a harmony based on the mutual aesthetic proclivities of the host and guest. The gathering takes place in a tranquil abode, a sort of microcosm isolated from the world of everyday cares, where a sense of absolute equality and propriety reigns, established according to the basic precepts of harmony, respect, purity, tranquillity (wa kei sei jaku) – qualities otherwise expressed as reserve, reverence, restraint – which guide all considerations of beauty. D. T. Suzuki explains that these principles of harmony and reverence stem from Confucianism, purity from Taoism and Shintoism, and tranquillity from Taoism and Buddhism, which suggests that the global appeal of the tea ceremony in Japan might in part derive from its highly syncretic nature.17 In the West, a dinner party may indeed turn out to be a ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ experience, but this is usually judged retrospectively, the sign of a particularly successful event whose transitory nature is bemoaned. In Japan, this sentiment of uniqueness is prospective, a goal rather than a result, where the transitory is cultivated and celebrated. This is accomplished by means of the thematic organization of the event, such that the sundry objects of the ceremony – the tea utensils such as the bowl, caddy, water basin and brazier; the flower arrangement, scroll painting or calligraphed poem (until the late nineteenth century, mainly writings by Chinese or Japanese Zen monks were so displayed); and the kaiseki meal that precedes the ceremony – all subtly allude to a particular theme and a specific season. Since the tea room is a place of heightened concentration, codified ritual, exquisite manners and refined aesthetics, the tea ceremony has a direct influence on the production and appreciation of art objects. Richard L. Wilson explains that ‘in Japan, the art object is perceived not as autonomous, but as an inseparable part of a historical and social nexus. “Intrinsic” qualities of beauty or genuineness are secondary in importance to the authority of past and present owners and admirers.’18 The ceremonial suitability of things, both artificial and natural, is as important as their intrinsic beauty, provenance, rarity. The beauty of an object is inseparable from the history of its use, and each tea ceremony deepens that history. Such is an aesthetic of use value in many senses of the term, from the primacy of functional objects to the centrality of gesture and the importance of ownership. Material culture here obtains a profound dimension.19

Established in response to the luxury, magnificence, extravagance and ostentation of previous Chinese-inspired forms of tea favoured by the imperial court, the wabi-sabi aesthetic stresses the perfection of the utmost simplicity, the ideal being that of the hermit’s hut in the mountains, a sensibility in line with the military austerity of the warlords who took power in the sixteenth century. Both aesthetics and connoisseurship in Japan are informed by these complex existential and conceptual matrixes, and Louise Allison Cort goes so far as to say that ‘the wabi ceremony has claimed the Japanese imagination with a power that far outlasted its period of vitality. It has permanently affected the way in which Japanese think about material objects.’20 Here, issues of authority, value and beauty refer to the originary moment – often fictively elaborated to the point of passing from history to myth – when the collaboration between Rikyū and Chōjirō (d. 1592), the founder of the Raku line of potters, established what have become the exemplary forms of both the ceremony and the tea bowl (chawan). According to Cort:

Whereas appreciation of Chinese masterpieces of acknowledged value had been a largely passive activity, the selection of native Japanese pots, as well as more modest imported goods – Korean bowls and namban jars – presented an active challenge to the individual imagination. Each tea man’s assemblage of utensils was a personal statement of taste. The role of the great tea masters – Jukō, Jō-ō, and Rikyū – was to discover and establish new possibilities for utensil types. Their experimental assemblages became the models that guided their students.21

Sen no Rikyū desired a uniquely Japanese pottery appropriate for the new form of the tea ceremony that he established so as both to escape from Chinese influences and counteract the growing ostentation that soon began to characterize tea under the regent Hideyoshi.22 Following Jukō (Shukō), who sought out the indigenous and austere works from the Bizen and Shigaraki kilns in contrast to classic Chinese types, Rikyū worked, according to legend, with Chōjirō to develop an original form of pottery of the greatest simplicity, the subtlest irregularity, the most austere rusticity. Not only did this collaboration revolutionize the art of pottery, but it also transformed the very mode of connoisseurship and set a new aesthetic paradigm, since tea bowls would now be made, at least in part, according to the specifications of the tea master. Henceforth, creative intuition, rather than rote erudition, would guide the production and use of tea vessels. This shift from tradition to invention, from a form of connoisseurship that was an erudite appreciation of an ancient foreign taste to one that foregrounded indigenous creativity, had both political and aesthetic implications, since it was a radically new source of wealth, power, beauty and knowledge. The rise of the centralized state concentrated power in the regent, with the sole exception of aesthetic judgement, which was the domain of the tea masters. This is doubtlessly the main reason for Rikyū’s tragic fall: not only was he guilty of lèse-majesté, profiteering from the pottery trade and court intrigues, but the very essence of his activity as tea master and aesthetic counsellor of the new form of tea placed him in direct and profound conflict with Hideyoshi, who could not countenance Rikyū’s aesthetic superiority. Rikyū revolutionized aesthetics by situating the discernment of beauty within the realm of immanence, such that the tea master’s taste became the absolute arbiter of aesthetic value. Connoisseurship was transformed into a veritable creative act. It has remained such to this day.

Chōjirō, Raku chawan named Omokage (‘profile’), late 16th century.

TALES OF ORIGINS are useful in focusing on a specific issue and setting a specific paradigm, though we have long been wary of such myths and their ideological implications. However, it is not only the spuriousness of origins, but also the very intricacy of time itself, that complicates such research. This is a fortiori the case concerning landscape and gardens. The land artist Robert Smithson once famously claimed: ‘You know, one pebble moving one foot in two million years is enough action to keep me really excited’, an excellent reminder of the radical temporal differences separating the human and natural orders.23 And even this pace is extremely rapid, if one considers the span of aeons (kalpa) in Buddhist and Hindu theology, where the largest unit of measurement is the great kalpa, lasting 1.28 trillion years, which may be visualized as longer than the time it takes a mountain of approximately 2,000 cubic miles – much greater than Mount Everest – to be completely worn down if every 100 years it is wiped once with a small piece of silk, or, in a more poetic formulation, the time it takes a rock brushed by an angel’s wing every three years to wear away. In a less hyperbolic context, it must be stressed that anachronism is at the core of chronology and iconography, of symbolism and narrative.24 That a garden element endures while everything surrounding it changes hardly makes of it an isolated, stable object. What appears as unequivocal presence is always a palimpsest of effects and forms, causes and effects, reality and myth, a dense web of significations and temporalities well beyond conscious comprehension and historical determination. One need only establish the chronology of each major detail of a garden to discover the site’s complex and anachronistic structures. Or perhaps it would be more precise to use the term ‘polychronistic’ to describe better such relations. Of all art forms, gardens are most susceptible to the ravages of time, especially as their temporality is so finely, and often brutally, attuned to season and climate, history and catastrophe. All gardens must be considered according to their sundry, and often contradictory, transformations, such that the reality of any garden is one of complex, overlapping and often anachronistic temporalities.

Landscape history has long suffered from what I would call the ‘curse of Hegel’: due to their materiality and heterogeneity, gardens were relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy in this classical aesthetic system. However, in our contemporary post-postmodern moment, these are the very characteristics that make the garden a privileged site, where time is felt in its palpable presence. The changes wrought by time have both natural and artificial causes. The Princesse Palatine observed that during the reign of Louis XIV there was no place at Versailles that had not been modified ten times, stressing the rapidity of artificial change suffered by these gardens. Natural changes may be more immediate and catastrophic, or more subtle and considerably slower, such that we must consider the particular importance of extra-human timescales in Zen gardens, not only concerning the imperceptible growth and apparent stability of lichen, so intimately associated with lithic existence, but also the very formation of rocks themselves. The temporality of gardens is extremely complex, operating on several levels: natural, phenomenological, iconographic, historical. One must consider the very different time frames of daily and seasonal cycles, the changing light and meteorological conditions, the slowly growing moss, the even more slowly crumbling stone, and the hands of gardeners, whether they be creative or destructive.

Ryōan-ji is a hyperbolic example of such perpetual and exceedingly slow transformation. Along with Versailles, Ryōan-ji is the most written about garden in the world: it would take an encyclopedia to chart out all its historical, formal and iconographic features. Mention of just a few of the salient moments will give a sense of the extraordinary richness of the garden’s history and symbolism, and serve as a corrective to those many readings that simply stress purity, abstraction and emptiness. Not merely a religious and aesthetic site, Ryōan-ji (literally, Temple of the Peaceful Dragon) is also an icon suggesting ancient myths, an aid to contemplation, an image of utopia, a touristic distraction, a commercial enterprise, a site of power, a nexus of belief. In Japan, iconography is often complicated by the permeability between Shinto and Buddhism, between the various forms of Buddhism (for example, Pure Land, Five Mountains and Zen), and between the various schools of Zen (such as Rinzai Zen and Sōtō Zen). The iconography of the dry Zen garden is thus highly syncretic, and is hardly limited to the unrepresentable intuitions of Rinzai Zen that had become so important to Western artists in the second half of the twentieth century.

Given the longstanding and extreme syncretism of Shinto and Buddhism, one might surmise that the expanses of bare raked gravel in Zen gardens are derived from the empty sacred spaces of Shinto sanctuaries with their beds of gravel, piles of stones, sacred rocks and cones of sand, while the scenic rock formations have their distant origins in the utopias of Chinese Buddhism, often inspired by the specific Chinese landscapes refined in Song epoch (960–1279) painting. The influence of Chinese iconography is further complicated by three minor but fascinating curiosities: scholars’ stones, dream stones and what the Japanse term suiseki (water stones). Scholars’ stones, also known in the West as ‘viewing stones’, are called qishi or yishi in Chinese, which means ‘fantastic rocks’, names that carry connotations of the unusual, strange, wonderful, special. Like their larger homologues found in Chinese landscape gardens, they are often sculpted (unlike Japanese rocks, which are nearly always left in their natural state) to resemble the most extraordinary mountains of China, famously represented in painting and poetry. The stones, set on elaborate wooden bases and placed amidst the accoutrements on a writing table, are held in great esteem among Chinese scholars and collectors.25 Dream stones, what the French term pierres paysagées, are rocks whose cross-sections reveal fantastic landscapes, on the cusp between abstraction and figuration. Suiseki are pebbles or small stones that evoke entire landscapes, selected according to the tenets of the wabi-sabi-shibui aesthetic, and mounted on fitted bases or even combined with bonsai. They are valued precisely for their representational associations, and their categorization (by shape, colour and surface pattern) recalls that of the much larger stones set in dry gardens: mountain stones, waterfall stones, island stones, shore stones and so on.26 Yet in all cases, whether miniature or natural, the landscape has both practical value as a site for seclusion, solitude, meditation and the escape from mundane and courtly existence – a reclusion symbolized by the solitary hermit’s hut – and a deep symbolic value, especially concerning mountains, as the realm of loftiness, transcendence and freedom, as well as of ghosts and spirits. Furthermore, as Joseph D. Parker explains, ‘since it was not the exclusive domain of any particular religious, philosophical, or literary school, writing about the landscape was one site for the proliferation of various syncretic integrations of different intellectual traditions.’27 Much the same might be said for the appreciation of landscape in all its manifestations, such as in gardens, poetry and pottery.

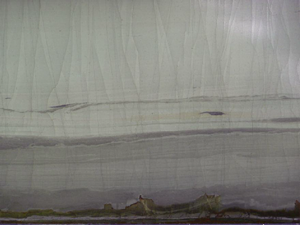

The stones of Ryōan-ji can benefit from such comparisons, which greatly complicate and enrich the interpretation of the garden. For example, consideration of the aesthetics of dream stones might well inform the appreciation of the astonishing aburabei-style walls, made of clay steeped in oil, that surround the dry garden of Ryōan-ji and establish its cloistered space. Nearly all discussions of Ryōan-ji focus almost exclusively on its rock arrangements, and rarely is mention made of the walls, themselves national treasures, that surround the dry garden. Centuries of weathering have caused the oil to seep out in irregular mottled patterns, which along with a palimpsest of repairs makes these walls reminiscent of dream stones or, to make a more contemporary comparison, resemble certain paintings by Clyfford Still. But perhaps a more fundamental resemblance, in the Japanese context, is the distinct similarity to patterns on certain types of high-fired Bizen pottery. For what, after all, are these walls but a form of pottery, clay baked and aged by the sun, albeit rarely recognized as such? These walls are veritable lessons in Japanese aesthetics, instantiating the subtle relations between figuration and abstraction, determinacy and indeterminacy, wilfulness and serendipity, denotation and connotation, revelation and suggestion. The walls of Ryōan-ji emblematize the slow, ever-changing effects of the weather over centuries, in stark contrast to the melancholy effects of instantaneous and ephemeral events. These walls constitute the irregular background against which appear the well-ordered forms of the garden, the chaotic ground of the sublime intuition.

Ryōan-ji, detail of aburabei wall.

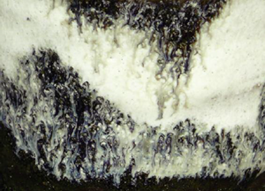

Ryōan-ji provides perhaps the most extraordinary example of such aleatory art, but close examination reveals similar phenomena in many Kyoto temples. Another beautiful example exists at the little-known Saishō-in, a subtemple of Nanzen-ji, where the walls, set in a mountain gorge and thus subjected to extreme humidity, have been allowed to develop a thick coating of moss and lichen that has taken on fascinating patterns. Though not a catalogued treasure, nor even an indicated tourist attraction, the fact that this wall has not been renovated for many years attests to its aesthetic interest. Such effects, though rarely noted, are apparently treasured and can be found in many temples and residences. For example, consider certain stains on walls at Eikan-dō that resemble a form of Karatsu glaze derived from Choson (Korean) pottery, or several striking instances on the grounds of the Kyoto house of the landscape architect Shigemori Mirei. One would have to deduce that, given the cultural and theological compulsion to order, cleanliness and purity that generally reigns in Japanese society and even more specifically in Shinto and Buddhist culture – where cleanliness is a metaphor for enlightenment – all sorts of apparent degradation when left untouched might well be considered wilful aesthetic effects.

Kakurezaki Ryūichi, Bizen guinomi, 2005, detail. |

|

Saishō-in, a subtemple of Nanzen-ji, detail of wall weathering and lichen.

But not all essential transformations are natural. Gardens, one must remember, are not only perpetually tended, but also often replanted and occasionally completely transformed. The dry garden of Ryōan-ji has often been transformed by the human hand, though it would be practically impossible to determine how many times and in what manner. For example, Japanese temples, which in any case are renovated at regular intervals, are notoriously fire prone. The original abbot’s quarters at Ryōan-ji burned down in 1797, and the building that now occupies the site is actually the abbot’s quarters from Seigen-in, a subtemple of Ryōan-ji built in 1606 and moved, along with its paintings, as a replacement after the fire. The building is thus an architectural anachronism, indeed a discrepancy, in relation to the garden, created around 1499. Furthermore, if one were to believe old woodblocks, at certain moments in its history visitors were allowed to stroll within the dry garden, something we can hardly imagine today. The sixteenth-generation Kyoto gardener Sāno Touemon remembers playing among the stones in the dry garden of Ryōan-ji as a child before the second World War. While this speaks more to modern neglect than aesthetic transformation, it nevertheless indicates the constantly changing aesthetics, use value and fame of the garden.28 One might also wonder whether moss was always present, or how often overhanging branches were permitted to trouble the straight line of the walls, or whether the sand was always raked, and if the patterns have changed, as certain woodblocks seem to suggest. The other gardens surrounding the abbot’s quarters at Ryōan-ji have also often been transformed, but in fact the fame of the dry garden has so eclipsed the other parts of the site that the contiguous gardens on the other three sides of the temple building – a moss garden, a stone and moss garden and a pond that gives on to the tea house – are practically never analysed in studies of the temple.

Eikan-dō, detail of wall weathering.

|

Koie Ryōji, Choson Karatsu guinomi, 2010, detail. |

Shigemori Mirei house, Kyoto, detail of pavement weathering. |

|

|

Matsuo shrine, detail of wall weathering. |

But one change above all should hold our attention, especially since it has been generally neglected in Western studies of the dry garden. Concurrent with the political and social watershed following Oda Nobunaga’s unification of Japan in the late sixteenth century, specific iconographic transformations celebrated the cultural achievements of the samurai, the new protectors of the monks.29 The universal fame of Ryōan-ji is certainly in part due to its role as a symbol of the apogee of Japan’s glory, just as the fame of Versailles endures as a hyperbolic expression of national unification, courtly splendour and divine royalty. Most important in these considerations of historicity and aesthetic anachronism is the fact that the iconography at Ryōan-ji was completely changed in 1606, when the sedate monochrome ink paintings of landscape, bird and flower motifs were replaced by extravagant, brightly coloured, gold-leaf-backed scenes of the Eight Immortals revered in Taoism. While the abbot’s private quarters still housed the old monochromatic-style paintings, suggesting a theological continuity with more ancient forms, the new polychrome works exhibited in the ceremonial rooms catered to a radically different mentality, that of the considerably more ostentatious taste of the warlords. Temple paintings no longer served only as aids to solitary meditation but also became ornate elements of festive luxury. A new symbiosis developed between the sacred and secular worlds, exemplified by the tea ceremony and poetry readings. In this period when class barriers loosened such that aristocrats, samurai, priests and artists intermingled for the first time, the new polychrome style was prominently displayed in the public areas of the temple facing the dry garden, the site where the interchange between public and private, political and priestly, was most intense. Curator Onishi Hiroshi remarks:

Thus Ryoanji’s shicchu [the ceremonial room of the abbot’s quarters] – very likely the first to have Chinese narrative themes in gold leaf – marks the culmination of a dialectical exchange between Zen monks and samurai patrons. The samurai leaders took over and remade images already prominent in Zen culture, while the Zen monks transformed their religious space as samurai influence flowed back into the Zen milieu.30

In this context of radical political and aesthetic transformation, the meditative, aesthetic and ceremonial use value of the dry garden could not have remained unchanged.

Dry gardens generally face a set of sliding wall panels (fusuma) in the temple rooms opposite them, panels that are often painted. In several famous instances, the iconography of the panels and the forms of the garden are homologous. A famous example is that of Jukō-in (a subtemple of Daitoku-ji). The stone arrangements of the main temple garden are strikingly similar to those in the painting by a follower of Kanō Eitoku (1543–1590), Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, set directly opposite the garden of the main hall of the abbot’s quarters, called the Hyaku Seki no Niwa (Garden of the Hundred Stones). In fact, this work was painted in 1583, the year that Sen no Rikyū designed the garden facing the painting in collaboration with Kanō Eitoku, who made the preparatory sketches. Painting and garden are of a piece. In other instances, the rock arrangements in a garden may represent the exterior landscape, as is the case in Shinnyo-dō, where the silhouette of the garden’s main stone arrangement almost exactly resembles the outline of the peak of Daimonjiyama, the highest mountain in the Higashiyama range of eastern Kyoto, framed in the garden by a captured view (shakkei). In the case of Ryōan-ji, the relation between such painted images and the gardens opposite them is almost never discussed, probably because the paintings disappeared long ago, having been removed from the temple and sold in 1895, during the time of the Meiji persecution of Buddhism, and only recently coming to light. These paintings, placed in the three rooms facing the garden (the public entrance, ceremonial room and patron’s room), respectively represent motifs of Tiger and Bamboo, The Chinese Immortals and The Four Elegant Accomplishments. The relation of their iconography to the dry garden that preceded them is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it would be imprudent to assume that the meaning and use value of the garden remained unchanged faced with the radical iconographic shifts accompanying the political and social watershed following the unification of Japan. The jagged, irregular rock formations on the screens and in the garden are strikingly similar, and the empty gold background depicted in these paintings is aesthetically congruent with the empty fields of raked sand in the dry garden. Both scenes are supernatural, and thus obey different laws from those of the natural and human world. Insofar as this new iconography represents the idealized, utopian landscapes of the Chinese immortals, might not the garden be phantasmatically imbued with such utopian scenography, antithetical to the void that it so often represents in current interpretations influenced by Rinzai Zen?

Shinnyo-dō, captured view of Daimonjiyama.

This iconographic shift, as it reflects the groundbreaking social changes of the epoch, is not incidental to the garden, but essential to its very meaning. Even the most cursory examination reveals distinct similarities between the lithic outcrops depicted in these paintings and the stone formations in the dry garden of Ryōan-ji, suggesting that both are not mere flights of the artistic imagination, but rather creations informed by the lineage of a fully developed iconography. These correspondences are of prime interest, whether such images were contemporaneous with the creation of the garden as at Jūkō-in, or followed it as at Ryōan-ji. That a rock fresh from the Kamo River near Kyoto could represent an ancient Chinese utopia is not a sign of ideological misrepresentation, but rather of the profound richness of symbols, the syncretism of cultures and the labyrinthine meanderings of history. To neglect such correspondences is to misrepresent ideology and to falsify history. Such complexity, contradiction and paradox is typical of Zen gardens, which – even if radically different from the roji (dewy path) gardens created to lead to tea huts – fully partake in the aesthetic complexities of the Zen-inspired tea ceremony. As we know, Zen thrives on such paradoxes. These historical and cultural layers relate Ryōan-ji to a theological paradox, the terms of which are a hieratic utopian iconography and a mystical naturalist iconoclasm, enriched by several strands of Buddhism, notably that of the Rinzai, Five Mountain and Pure Land schools, as well as Shintoism, Taoism and Conficianism somewhere in the mix.31 Extreme syncretism is enriched by radical anachronism.

|

Circle of Kanō Eitoku, scene |

Chinese Immortals, c. 1606, Ryōan-ji.