ONE

TRANSIENT SYMBOLS

One of the classic Japanese tales adapted by the Noh theatre, Ugetsu, concerns the itinerant poet and monk Saigyō (1118–1190). One evening he arrived at a very dilapidated hut with a good part of the roof missing, and requested shelter for the night from the elderly couple who lived there. The man politely refused, explaining that their abode would be unworthy, but the wife, seeing that the traveller was a monk, wished to accommodate him. The problem was that the woman loved the moonlight so much that she did not want the roof repaired so the moonbeams could stream into the house, while the man preferred the patter of the rain and thus desired a suitable roof. As autumn was approaching, the situation became even more serious, since this was not only the best moon-viewing (o-tsukimi) season, but also that of the most delectable rains. The couple asked the monk:

Our humble hut –

Is it to be thatched, or not to be thatched?

The monk responded by saying that they had just composed a fine, though incomplete poem, in response to which they suggested that if he could complete the poem, they would lodge him, whereupon he proclaimed:

Is the moonlight to leak?

Are the showers to putter?

Our thoughts are divided,

And this humble hut –

To be thatched or not to be thatched.

He was invited in, and as the night deepened, the moon advanced and finally entered the house. Soon afterwards they heard the sound of rain on the horizon, only to realize that it was in fact the rustling of leaves – a shower of falling leaves in the moonlight.1 This poignant tale is a veritable allegory of Zen aesthetics, where paradox (the impossible simultaneity of moon and rain) is resolved by metaphor (leaves as rain).

Bashō, founder of the modern style of haiku, writes of the extreme love of nature among certain Japanese artists: ‘Whatever objects he sees are referred to the flowers; whatever thoughts he conceives are related to the moon.’2 Indeed, many critics claim that one of the most moving, indeed sublime, moments in The Tale of Genji is when Genji pays a night-time visit to one of his loves, to find the door ajar and the moonlight streaming in, prefiguring his entrance into the room. D. T. Suzuki beautifully evokes the Japanese love of the moon and its centrality in the Japanese imagination:

The moonlight singularly attracts the Japanese imagination, and any Japanese who ever aspired to compose a waka or a haiku would hardly dare leave the moon out. The meteorological conditions of the country have much to do with this. The Japanese are lovers of softness, gentleness, semi-darkness, subtle suggestiveness, and everything in this category. They are not fiercely emotional. While they are occasionally surprised by earthquakes, they like to sit quietly in the moonlight, enveloped in its pale, bluish, soul-consoling rays. They are generally averse to anything glaringly bright and stimulating and too distinctive in its individuality. The moonlight is illuminating enough, but owing to the atmospheric conditions all objects under it appear not too strongly individualized; a certain mystic obscurantism pervades, and this seems to appeal to the Japanese generally.3

Though this estimation of the Japanese soul might not be evident while strolling today in Ginza, Tokyo’s most prestigious commercial district, or in Shibuya, a forest of neon lights, the lunar attraction is the very essence of the Zen sensibility. Zen has even been defined as ‘a finger pointing at the moon’, as its eternally waxing and waning glow covers the entire world with a patina of spectral light. One of the classic autumn motifs is the full moon appearing through pampas grass, often seen in paintings and drawings, kimono patterns, decorated screens, lacquerware, pottery and even in food arrangements. For example, tsukimi-wan (‘appreciating the full moon’ soup) is a dashi and shoyu-based clear soup (kelp and bonito stock; soy sauce), usually served in a black lacquer bowl and garnished with a floating, paper-thin circle of daikon radish or grated yam shaped into a ball, on which are scattered a few bits of mitsuba or some other herb, or perhaps chrysanthemum petals or slivers of vegetable, arranged to look like the moon seen through wild grass. It is said that ‘The moon is not pleasing unless partly obscured by a cloud’,4 or else seen through a stand of bamboo, the branches of a pine or, most traditionally, the grasses of autumn. Such eclipsing is emblematic of Japanese aesthetics, from the many screens that divide the space of the traditional house to the mud walls and bamboo fences that circumscribe the space of the Zen garden. This reveals the taste for incompletion and imperfection central to wabi-sabi aesthetics.

To say that iconography is codified is to imply that ways of seeing are classified, ordered, methodized, hierarchized, systematized. Such organization of images and perceptions does not limit aesthetic possibilities, but rather opens up many unexpected horizons. It is just as wonderful to learn to see as did the poets and painters in classic times as it is to discover new ways of seeing. No object, natural or artificial, falls outside this aesthetic purview, for our sense of nature is profoundly inflected by our culture. I have seen the dry garden of Ryōan-ji in full sunlight and in shade, in rain and snow, at dawn and dusk. And though I have seen photographs of it illuminated by moonlight as well as by electric light, I have never actually experienced it at night, and may never have the occasion to enjoy it under any moon, whether new or full. This should not, however, limit my appreciation, but rather expand it, since longing should be part of every aesthetic act. The moon can be enjoyed elsewhere, otherwise, in many ways that are sheer poetry. There exist, for example, numerous moon-viewing pavilions in Japan, perhaps the most famous attached to the Geppa-rō tea house located at the Katsura Detached Palace near Kyoto. One of the most popular rituals is to raise a cup of sake so that it reflects the first full autumn moon – the moon of great melancholy, marking the moment when life begins its decline – to then drink down the sake and the moon in the same draught. Though the moon often infiltrates the tea room, tea is not the only elixir in Zen culture.

Here, the highest aesthetic may reveal the greatest grace. Japanese monks and poets have a tradition of writing death poems, like that of the modern poet Baiko (d. 1903):

Plum petals falling

I look up – the sky,

a clear crisp moon.5

The melancholy of passing captures the author in its motion, where for the only moment in the poet’s life the instantaneous, unique event celebrated by the haiku is his own disappearance; where time passing and time transfixed are one.

DEATH IS GENERALLY deemed a taboo topic, and some make its avoidance an ethical imperative. In the words of Theodor Adorno, ‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.’ The same may be said concerning Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And should we not again consider this injunction following the great Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and the nuclear catastrophe that followed at Fukushima?6 One may, however, wonder about the limitation of Adorno’s iconoclastic injunction to specifically poetry among all the arts, which may be partially explained by the fact that he was fundamentally more musician than poet. The most poignant rejoinder would be to cite Paul Celan’s ‘Todesfuge’ (‘Death Fugue’, 1948), which suggests – utilizing a musical imagery that must certainly have moved Adorno – that one actually has an obligation to write such poetry, that only a more profound poetry of death can counter the death of poetry.

He shouts play death more sweetly this Death is a master from Deutschland

he shouts scrape your strings darker you’ll rise then as smoke to the sky

you’ll have a grave then in the clouds there you won’t lie too cramped . . .7

The image of bodies gone up in smoke is common in Japanese culture, which has long practised cremation, as witnessed in The Tale of Genji at the moment when Genji laments the death of his wife, Aoi: ‘No, I cannot tell where my eyes should seek aloft the smoke I saw rise, But now all the skies above move me to sad thoughts of loss.’8 However, while in many cultures such immolation is an integral part of a ritualized work of mourning, in Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, the ritual was abolished, the mourning violated, the tomb not merely desecrated but annihilated. Such images must always be presented with the greatest of discretion and trepidation, yet they must be presented, over and over, not only so that we never forget, but also so that we can mourn, sublimate and plumb the depths of their horror.

Still from Ikebana (dir. Teshigahara Hiroshi, 1956).

One of the most unexpected, indeed bizarre references to the catastrophe of Hiroshima occurs in Teshigahara Hiroshi’s film Ikebana (1956), a documentary about his father, the ikebana master Teshigahara Sōfū who established the Sōgetsu (grass-moon) school of flower arrangement that revolutionized the art form by bringing it in line with the mid-twentieth-century avant-garde. The film is a somewhat whimsical presentation of this new form of ikebana, exhibiting the radically new forms sought by Sōfū, as revealed in the scene where he makes an arrangement consisting mainly of dead, calcinated branches and dried plants, the totality appearing as a stylized conflagration in a forest. The occasional use of such withered materials would be appropriate in traditional ikebana either for visual emphasis or to mark seasonal symbolism, just as dead branches and simulated lightning damage are used in bonsai (miniature plants) for verisimilitude and dramatic effect, and in other instances it might even produce a pleasant surprise, as Edward S. Morse explains regarding a bonsai of plum trees set in a garden:

Before the evidence of life appears in the blooming, one would certainly believe that a collection of dwarf plum-trees were simply fragments of old blackened and distorted branches or roots, – as if fragments of dead wood had been selected for the purpose of grotesque display! Indeed, nothing more hopeless for flowers or life could be imagined than the appearance of these irregular, flattened, and even perforated sticks. They are kept in the house on the sunny side, and while the snow is yet on the ground, [they] send out long, delicate drooping twigs, which are soon strung with a wealth of the most beautiful rosy-tinted blossoms.9

But Teshigahara Sōfū displays the flowerless dead wood as the very core of the work, an icon of disaster, proferring a morbidity beyond the bounds of formal exigencies and good taste. At this point, however, the film suggests little more than a particularly idiosyncratic, and perhaps somewhat audacious if not contentious, gesture of formal innovation.

We might remember in this context that one of the classic statements on Japanese gardens, Illustrations for Designing Mountain, Water, and Hill side Field Landscapes, composed by the priest Zōen (fifteenth century), includes the following injunction: ‘Bearing in mind the Five Colors of rocks, you must set them with full consideration of the relationships of Mutual Destruction and Mutual Production.’10 This suggests that the power of nature as active principle, natura naturans, is always looming, and that certain forms of destruction are perhaps appropriate to the composition and elaboration of the dry Zen garden (karesansui, ‘withered mountain water’). Indeed, many of the great Zen gardens were destroyed by fire, war, earthquakes and floods, and certain aspects of garden design are used to highlight the cyclical processes of the natural world, such as leaving tree stumps to disintegrate, rather than totally uprooting them as would ideally be done in most Western gardens. Decay and destruction are an integral aspect of Zen-inspired aesthetics, profoundly related to the temptation of the void. To see Teshigahara Sōfū’s arrangement of dead branches simply as an innovative manifestation of modernism would be to miss its profound connection to classic expressions of melancholy.

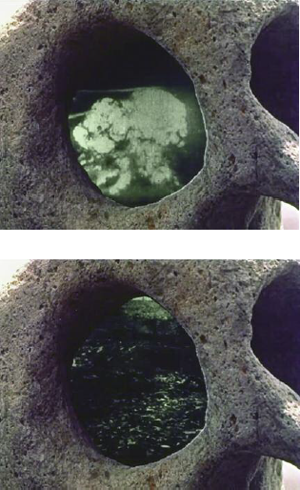

It is not until the final scene of Ikebana that, despite the seemingly innocuous and aestheticized subject-matter, we are witness to one of the most horrendous images of the twentieth century. The camera pans across a broad expanse of beach to reveal several sculptures by Teshigahara Sōfū, to pause finally on one of them and zoom in to the head shaped in the form of a skull. All of a sudden, in the hollow of the left eye socket, appears an atomic explosion, followed by a brief shot of Hiroshima in ruins, in all about thirteen seconds of film. Here we have symbol, icon and index of the greatest instance of annihilation in history: the eternal symbol of the death’s head; the cinematic icon of an atomic explosion and the ruins of Hiroshima framed in the empty orbit; the luminous traces of the explosion itself that constitute the cinematographic index of all that was vaporized, burnt and irradiated by that nuclear holocaust.

Two years after Teshigahara Hiroshi created this extraordinarily unsettling, indeed almost unthinkable montage – where the life-giving waves of the eternal ocean fade into the hyperbolic destruction of the instantaneous atomic blast – the great photographer Domon Ken published his book Hiroshima (1958), the harsh realism of which reveals the aftermath of the city’s catastrophe. A year later saw the performance that launched Butoh, Hijikata Tatsumi’s Kinjiki (Forbidden Colours, 1959), the spirit, iconography and choreography of which was profoundly influenced by these events.11 One might go so far as to suggest that the nuclear holocaust in Japan signalled a radical rupture in the iconography and theatrics of death, divided between the superlatively aestheticized ghosts made visible in traditional Noh – with their resplendent costumes, entrancing masks, extraordinary choreography and fabulously convoluted plots – and the invisible radiation whose effects are horrifically symbolized in the ashes and contortions of Butoh, the ‘dance of darkness’.12

A decade later, Hiroshima became the symbol of a revolution in architecture and aesthetics when Isozaki Arata exhibited the Electric Labyrinth installation at the Milan Triennale (1968), part of which was the collage Hiroshima Ruined Again in the Future, superimposed on a photograph of Hiroshima just after the atomic bomb had been dropped. This apocalyptic image of destruction and extinction is simultaneously witnessed by Isozaki as the death of all the utopias of the modernist avant-garde and as the sign of a new beginning in architecture and urbanism. ‘Ruins are the style of our future cities’,13 he proclaims, explaining that the city is a process, and that its traumas must be depicted. Seeming to echo Zōen’s injunction about mutual destruction and production, Isozaki explains: ‘Bringing the city to be constructed back to the city that had been destroyed emphasized the cycle of becoming and extinction.’14 In support of this claim, he refers to the aesthetic concept of sabi, the ‘dried and emaciated’, citing several classic Japanese sources.15 Sabi signifies patination by age or use, connoting, as Donald Richie suggests, ‘the bloom of time’ and its corresponding feeling of melancholy; in extreme instances this feeling can be one of bleakness and desolation.16 However, in traditional Japanese culture it is almost unheard of to make the ultimate extrapolation and directly relate the term to morbidity and death – not to mention its hyperbolic association with the atomic blast – as does Isozaki by associating sabi with the ‘frozen landscape of death’ at Hiroshima.17 Such ghastly imagery is tantamount to a provocation, for who could bear the profoundly anti-aesthetic thought of nuclear fallout as the sabi of the earth?

Soon after the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake that devastated Kobē on 17 January 1995, the Japanese Pavilion at the 1996 Venice Biennale was dedicated to ‘Architects as Seismographers’. In this venue, Isozaki re-exhibited Hiroshima Ruined Again in the Future, explaining that, ‘ruins were a source of the imagination’.18 Might we suppose that the greater the ruin, the more profound the imagination? Might this not suggest a new or terminal manifestation of the sublime? Are we not confronted with a radically new form of temporality, measured in radioactive half-life? Isozaki sensed that we had already entered a new epoch in the history of landscape and cityscape, where the nuances and limits of metaphors and symbols had been radically transformed.

Isozaki Arata, Hiroshima Ruined Again in the Future, 1968, project, ink and gouache with cut-and-pasted gelatin silver print on gelatin silver print, 35.2 a × 93.7 cm.

At times, the smallest is an allegory of the greatest. It is surely no coincidence that another of Domon Ken’s best-known works is Shigaraki Ōtsubo (1965), a book on large earthenware jars that revolutionized the representation of pottery, with its high-resolution photographs and extremely detailed close-ups. Writing in the 1960s of pottery from the town of Shigaraki, literary and art critic Kobayashi Hideo describes the site-specific relationship between earth and pottery: ‘The time I went to Shigaraki and gazed at the white earth and green forests of red pine, the idle thought drifted quite naturally into my mind that, if there were a forest fire here, it might well produce a gigantic Shigaraki pot.’19 The art historian Louise Allison Cort glosses over this fantasy:

Chance, the absence of human will, is the manifestation of natural innocence. Yet nature, according to this aesthetic, possesses a will of its own: the pots emerge as the creation of the ‘combat between the clay and the fire’ within the kiln. Collectively, the features created by this awesome combat are termed the ‘scenery’ of the pot. Certain aspects of natural ‘scenery’ are felt to be embodied, transfigured, in the pot itself.20

The pot figuratively represents the earth while it is materially of the earth. Regarding a culture where pottery can evoke the sublime, it is hardly frivolous to relate this art form to even the greatest of catastrophes.

The very creation of pottery is a cataclysmic event, a violent transformation of earth. The mythopoetic dimension of this sensibility is explained by Bert Winther-Tamaki:

The burning and vitrification of the clay in the kiln were imagined as a kind of condensation of the great spans of geological time that produce the rocky formation of the earth’s crust. In this analogy, the ceramic artist travels back to a geological past, mimics the igneous processes of the earth, and then returns to the present to claim the products of ‘superhuman time’.21

Thus pottery, in its most profound manifestation, is an allegory of the catastrophes of earth, fire, water. Certain types of unglazed, high-fired stoneware are particularly valued by pottery connoisseurs, and Murata Jukō, one of the originators of the Japanese way of tea, ‘equates the appreciation of Bizen and Shigaraki wares with profound spiritual attainment’.22 According to Cort, the appreciation of pottery concords with that of traditional poetry, insofar as ‘the beginner was advised to start with a “correct and beautiful” style, progressing only gradually toward expression of images described as “cold” (hie) and “lean” (yase) or, in the ultimate refinement, as “dried out” (kare)’.23 This suggests that only the most accomplished poets, which means only poets of a certain age, may allude directly to death, whence the rarity of its expression. The highest spiritual attainment is thus in part a recognition of our own mortality or, as Inoue Yasushi expresses it in his historical novel The Tea Master, through the words of the tea master Shōō (Jōō): ‘It is said that the quintessence of poetry is a cold, dry, exhausted universe . . . I would like that of tea to be similar.’24

Koie Ryōji, Shigaraki guinomi, c. 2008. |

|

Regarding the aesthetics of the tea ceremony, A. L. Sadler notes that in addition to the sundry shades of black and white, ‘in decoration their most favored hues are Ash color, Tea color and Mouse color’.25 This is so not only because such a dearth of bright colours is all the better to set off the ceramics and the flowers in the tokonoma (the alcove in the tea room where scrolls, pottery and flower arrangements are displayed), but even more profoundly because such are the colours appropriate to the sense of wabi rusticity and austerity. This ascetic sensibility corresponds to the ‘dry’ aesthetics of Zen gardens, which, like certain types of pottery, are valued precisely for their earthiness, austerity, irregularity, roughness. As signs of the solitude and melancholy central to the wabi-sabi aesthetic, the starkness of raw, troubled matter and lack of superfluous decorativeness are considered signs of heightened spirituality. Yet, however much the aesthetic of the ‘dry’ or ‘withered’ might suggest mortality, the visual representation of the morbid in tea culture is anathema. Rather, it exists in the most subtle allusions, referred to as mono no aware, the wistful thrill of the ephemeral, the melancholy of things passing, famously instantiated by the fall of a leaf or a petal, the melting of snow, the occultation by a cloud or fog, all gently signifying the transience of existence. It expresses both regret for time passed and relief in the Buddhist perspective of escaping from the worldy cycle of suffering. That the term aware occurs over a thousand times in The Tale of Genji is a sign of its importance. This refinement has been made familiar through the ages by the nearly obligatory presence of such references in haiku, poetry that revels in the evanescent without ever touching on the morbid. However, there exists one notable exception, the death poem (jisei), that final work composed as a parting gesture. In a sense, all manifestations of mono no aware are asymptotic to morbidity, just as all haiku are asymptotic to the death poem.26

In 1980 the potter Koie Ryōji created a work in India that consisted of ‘firing’ the ground with a blowtorch, a gesture that can be said to constitute a limit condition of pottery, if one takes into account the fact that while in English the word ‘pottery’ denotes the vessel-like form of the object, in Japanese yakimono (‘fired thing’) stresses the creative moment as the object passes through fire. One might well imagine, symbolically of course, that Koie would have been the ideal artist to have set that Shigaraki forest fire imagined by Kobayashi, in a gesture to celebrate the relation between human creativity and nature’s agency. Koie sought the extreme limits of pottery by reformulating the question at the centre of the tradition: ‘At what firing temperature does something become ceramic?’ This resulted in the production of a provocative monument in Hokkaido, created by filling a long, 10-centimetre-wide groove with molten aluminium. When questioned as to whether this is yakimono, he responded: ‘The aluminium was about 700 degrees centigrade, so the ground got burned. Therefore, it is yakimono. It is just a standing column, but it left a scorch mark on the ground. That’s like “Scar Art”.’27 This modernist performance is also an indirect allusion to the very origins of pottery in Japan: Jōmon works from approximately 10,000 BCE and older, fired in outdoor bonfires at 600–900 degrees celsius.28 Koie thus rethought the art of pottery according to the ontological limits of fire in relation to clay, the ultimate extrapolation of which is his series of anti-nuclear, anti-war pieces evoking the most extreme, deadly, horrific effects of fire. These include: Testimonies (1973), a trapezoid made of pulverized ceramics into which was inserted before firing a watch reading 8:15, the time of the nuclear explosion over Hiroshima; No More Hiroshima, Nagasaki (1977–present); Chernobyl (1989–present), a series of works, the one illustrated on page 194 consisting of pulverized Seto tea bowls on a brick base on which was placed a glass bottle that melted during firing; and Anti-Nuclear Water Container (1982), a white glaze mizusashi (water container), where the ironic rhetoric of the title attributes physically impossible prophylactic qualities to this work, while tacitly suggesting that the spiritual core of the tea ceremony can assuage the horrors of nuclear catastrophe. In the late fifteenth century a chief priest of Ryōan-ji made a claim that defined the Zen garden: ‘Thirty thousand leagues should be compressed into a single foot.’29 Half a millennium later, Koie would symbolically compress a nuclear catastrophe into a pot.

Paul Claudel, long-time ambassador to Japan and one of the French writers most attuned to the Japanese sensibility, wrote in L’Oiseau noir dans le soleil levant of the great Kantō earthquake of 1 September 1923, which destroyed Tokyo and caused over 140,000 fatalities, approximately the same number as the bombing of Hiroshima.

Over there to the left, the immense redness of Tokyo, to my right the Last Judgment, above me an uninterrupted river of sparks and flashes. But that would not hinder the moon, waning and almost consumed, to rise in a silver archipelago. Soon afterward I see Orion appear in the sky, the great constellation that is the voyager’s friend, the pilgrim of the sky that successively visits the two hemispheres. The moon began its course. Its hands stretch upon the sea, an ineffable consolation.30

Koie Ryōji, No More Hiroshima, Nagasaki, 1977, ceramic sculpture, 15.5 × 18.5 × 13.5 cm.

That he can evoke the autumn moon at such a tragic moment is all the more poignant as he traversed the devastated landscape in search of his daughter, whom he believed to have been lost in the catastrophe. This moonlight is the sabi of the world, like the spectral ambiance of Noh, connoting the ineffable tragedy of death.

Among the most reproduced and celebrated images in Japanese culture, the full autumn moon has long been one of melancholy, as in The Tale of Genji, which opens with the emperor lamenting the loss of his favourite consort: ‘When above the clouds tears in a veil of darkness hide the autumn moon, how could there be light below among the humble grasses?’31 Here too the moon could have offered inexpressible solace, but in its stead we are granted another form of ‘ineffable consolation’: poetry. Claudel’s moon, however, was not the full moon of traditional Japanese poetry, but a moon already waning: perhaps an omen of a new symbolism in the making. Claudel could not have imagined the nuclear tragedies to come in Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Chernobyl, Fukushima, nor the invisible evidence of radiation that would henceforth affect the future of landscape, nor the Butoh that would constitute a new danse macabre. But he already sensed that moon-beams could effectively counteract gamma rays.