UP IN the timber country they are putting the camps in shape for the winter cutting and I have to go there every so often to make plans with the bosses. Logging is not what it used to be forty years ago when big horses, the pride of the tote teamsters, did all the heavy hauling. Only a few horses are seen in the camps these days, for tractors have taken their place. They do a fine job, but I miss the horses, the shouts of the drivers and the sight of fine teams with vapor steaming up from their shining backs in zero weather. It was grand to see them snaking logs out to the skidways where the sleighs picked up their bunk loads and hauled them down to the banking ground by the river. Those were days when the push had to be a man who not only knew logging, but could knock down any lumberjack in the camp and keep order. They call him the foreman now.

There is no finer picture of teamwork than to see two good men making a sharp crosscut saw sing its way through a big stick. And for handling a double-bitted axe you can not beat those fellows in the logging camps. To watch one of them balanced on a downed tree, his axe flashing in the dazzling winter sunlight as he slashes off the limbs, is worth seeing. They used to spend a lot of time whetting the edges of their axes and I have seen a man prove an edge by shaving himself. When the trees fell the swampers got busy clearing away the limbs and brush so the teams could drag logs to the skidways.

Keeping the tote roads in good condition was important and all day long road monkeys were busy repairing places that broke down under the heavy loads. On cold, quiet nights when the frost cracked in the trees and the zero air burned in your nostrils with every breath, the sprinkler, a sleigh fitted with a big wooden tank, would go out over the roads, water trickling from two holes over the ruts to fill them in with new ice.

Teams often left the camp soon after three o’clock in the morning and in an hour there wouldn’t be anybody left there but the cook and his crew, the wood butcher, who built and repaired the sleds, and who could shave out a toothpick with an axe, and the barn boss who had charge of feeding the horses.

Nowadays most of the heavy work is done by tractors and in the silence of the woods you hear the roar of their engines that leave a trail of smoke that taints the good north air. That’s the way it has to be, for things have got to move ahead, and if there is a better and faster way of doing a job I am for it. Be that as it may, I will always be glad of my memories of men and horses working in the woods in winter and the great spring drives when the logs that were piled on the ice crashed through and started on their way down stream.

Sometimes the Chief comes along on my trips to the timber limits and on the last one we went up by way of Faraway See Hill to look over the country. We do that almost every year about this time, for in the fall the view from the top just about takes your breath away. It is a mite over four miles as the herons fly, but seven by the trail from my cabin.

When we got to the top of the hill where the winds of winter blow too hard for trees to live, we looked down on a giant-colored map made up of the scarlet of the maples and the bright yellows of the birches and poplars laid out on the dark green background of spruce and pine, with patches of lighter green where the tamaracks stand in the swamps; and in between lay the rivers and the lakes, blue in the sunlight, silver when a cloud passed across the sun.

Just before sunset we made camp by a brook at the foot of the hill and I cooked some flapjacks, bacon, and tea while the Chief built a shelter. Bending down a slender birch sapling until the top was about his own height, he lashed it with our tump line to a stake, and against it on both sides at intervals of a few inches he slanted dead spruce saplings. These he tied at the top with spruce roots and then beginning at the bottom shingle-wise, he laid on pieces of birch bark stripped from a dead tree, spiking the strips over the stubs of the spruce branches to hold them in place until he could pile on a thatch of balsam boughs. A long strip of curving birch bark laid along the ridge finished the job. It was as snug a shelter as a man could want, tight and warm.

Close by our camp was an out-cropping of iron pyrite, Fool’s Gold, and although I had not tried it for years, I made fire by striking two chunks of it together. When struck a sharp, glancing blow pyrite gives off sparks which can be used to kindle a fire. It is not as easy as it sounds, for there’s a knack to it, and you have to have good dry tinder. The Chief shredded some birch bark, but I failed to light it, so he got a piece of fungus, the kind that grows on dead birch logs, and scraped it with his knife until he had a little pile of powder on a strip of birch bark. Then after several tries I got it glowing and by blowing on it gently, we got a fire going. To be sure, matches are handier, but as pyrite is pretty common in these parts it is a trick worth knowing. It is an easier way of starting a fire than striking sparks with flint and steel.

To an Indian the woods furnish nearly all he needs for living, be it shelter, fire, or food. It was not by chance that we came upon that camping site with plenty of dry birch bark and saplings ready at hand. The Chief’s roving eyes had been watching for what he wanted. And it wasn’t just luck that there was a brook to give us water and a stand of heavy timber to the northward to shelter us in case the cold wind came in the night. Yet we had not gone out of our way nor wasted time in coming to the place.

On the trail the Chief walks as quietly as a lynx and his eyes see everything. Not an animal track is missed and he can pick up scents like a wild creature. “Moose not far,” he said soon after we had started on our way the next morning. Sure enough in a few minutes he pointed to fresh tracks crossing the trail, for this is Wisac, the Mating Moon, and the deer and moose are roving the forest. While stopping to study the tracks, the old man pointed out a stalk of grass slowly lifting from the soil into which it had been pressed by the hoof of the animal, and because the ground was dry little specks of soil crumbled from the edges of the hoofprint. Without saying a word, but by holding up his hands, touching his nose, and indicating direction he told me that the moose had passed not ten minutes before; that the animal had wind of us and was hurrying was shown by the distance between the hoofprints and their depth in the damp earth.

I have seen the Chief trailing a bear in light tracking snow and before he had gone very far he told me the bear was a large male and that he was in no great hurry or had no special place to go to because the tracks wandered hither and yon, which indicated that he was probably looking for food. That proved to be true for later on we came across several logs that he had clawed in search of grubs.

When an animal is running for its life its tracks are deep and clean cut, but when the beast is taking its time the prints are more likely to be blurred or shallow, and without sharp edges. Talking of bears, the Chief said you could tell a young one by sharp claw marks, while the claws of an old-timer, worn by much traveling, have rounded points.

Studying the tracks of a big dog wolf one day he explained that the animal was moving very slowly and had stopped once in a while to listen and pick up a scent, for the snow in some of the footprints was faintly glazed, showing that the animal had stood still long enough for the warmth of his foot to melt the snow which quickly froze when he moved on.

When as a youngster I began trailing game with the Chief he made sure that I understood that wild animals depend on scent, sound, and sight to protect themselves against their enemies. The hunter, therefore, tries to keep down wind from his game, moves very quietly and guards his movements. Ever watch a cat stalking a squirrel, creeping ahead when his quarry was not looking, freezing when it turned its head or showed signs of alarm? That’s the way the Chief gets close to a moose or bear. If the hunter is standing as motionless as a rock when the animal looks his way it may not recognize him for what he is, especially if he is in timbered country. But let him so much as twist his head or move a hand and the wild creature will see it.

Chief Tibeash likes to show how good a woodsman he is and at times I have found it hard to pick him out in the forest. Once I discovered him not twenty yards away, chuckling to himself because he had been coming up on me for several minutes, freezing in his tracks when I looked his way, silently hurrying on when I turned my eyes in another direction. “Good thing,” he said, “you are not a moose or you would be my meat.”

I recall the days when the Chief taught me how to call moose. After I had practiced with him for a while I went out one fall evening alone without a gun for a little calling on my own hook. I wandered down to a point on the east shore of Snow Goose Lake and let loose with my birch bark horn, rolling it toward the ground and raising it high just the way the Chief does. It was a quiet evening and after listening for a while I gave some more calls, ending up with a few mooselike grunts. When moose answer a call they may come tearing through the bush without thought of caution, but once in a while they steal up as quietly as a cat. That is just what happened to me. Not fifty yards away a big bull suddenly appeared on the shore. He saw me about the same instant that I caught sight of him, and I could see he was mad. It was my good luck to be standing near a big spruce with limbs that came down pretty low, and it didn’t take more than a jump and ten gasps to get twenty feet up that tree. The moose hung around for a while, snorting and pawing the ground, and then he went away. Then I started home like a snowshoe rabbit with a fox on his trail. It took me a week to begin to feel proud that I could call a moose.

A big bull suddenly appeared on the shore

If you called the Chief superstitious he would be angry, yet he and many other hunters and trappers have certain beliefs about hunting and fishing that have been handed down from generation to generation. One afternoon early this fall when the old man and I were sitting talking I noticed that he was listening to something else, and then all of a sudden he got up and went out the door very quietly. I had some meat on the stove so I didn’t follow him for a few minutes and when I went out he was standing under a tree looking up and talking his head off in Cree. It took me a minute to see that he was addressing several bluebirds which were then moving down on their way south. Every few seconds he would stop and listen, and finally I heard one of the birds chirp and then another. At that the Chief turned back to the cabin with an air of great satisfaction. The Indians in these parts believe that if you talk to the bluebirds before you start on a hunting trip and they answer, the hunting will be good, but if they make no reply then you can expect no game.

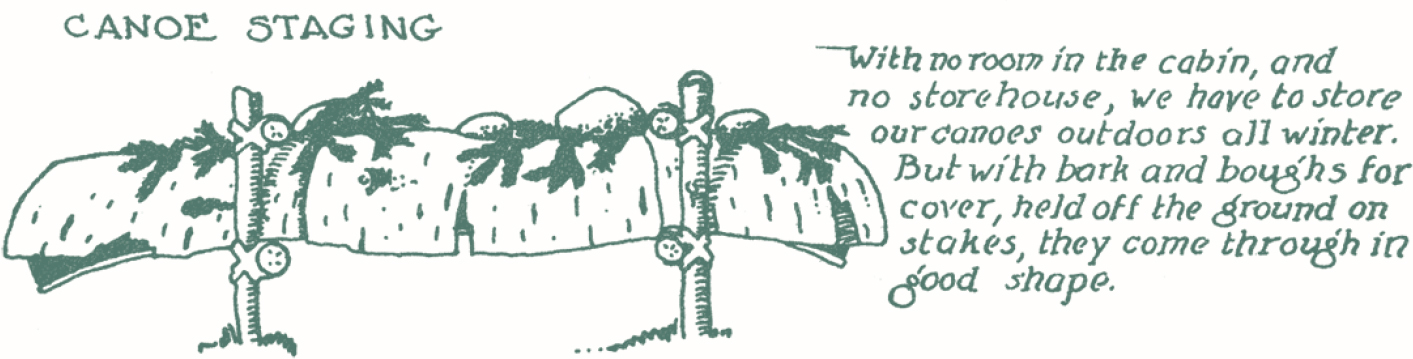

Aside from banking the cabin I have had a lot of other chores to keep me busy this fall. One of them was to build a new stage for my canoe at the back of the cabin where I store it under birch bark when the ice makes on the lake. I have also replaced the stay wires on my chimney pipe, for the fingers of the winter gales are strong and searching, and checked over the roof and tarred some of the seams. A good tar paper roof is hard to beat if you keep it tight.

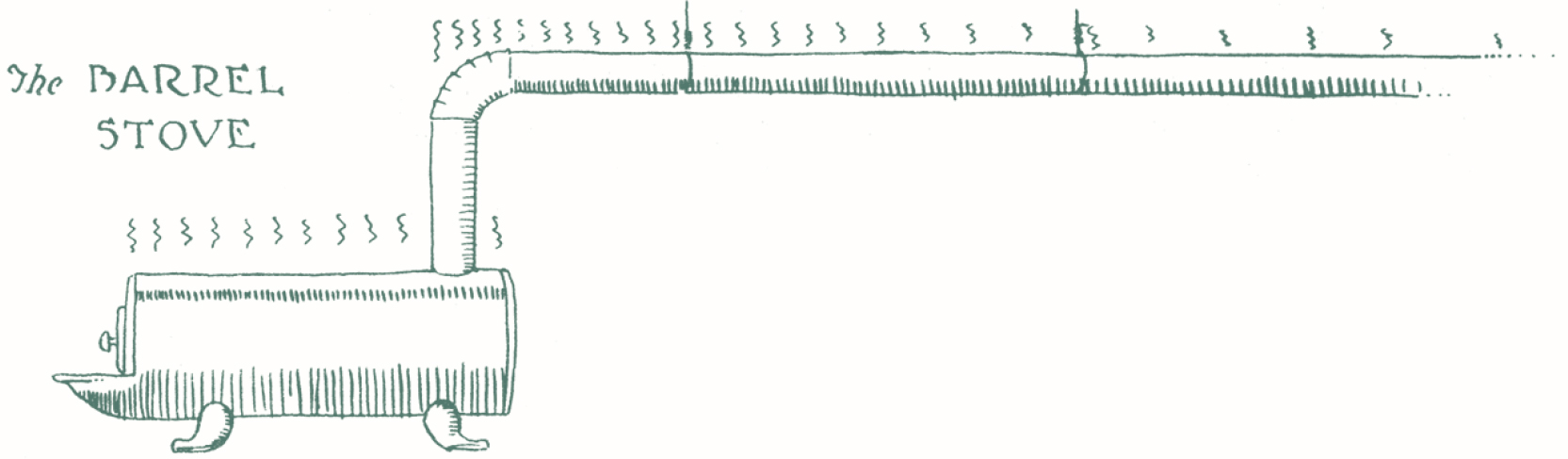

Inside I have set up my old barrel stove which with the cookstove keeps me as warm as I please all winter. That kind of heater, which some call a drum stove, gives off a lot of heat and I get an extra supply by using a long pipe that runs down the middle of the cabin and then across to the chimney. You would be surprised the amount of heat a long pipe will throw off instead of pulling it all up the flue. When it comes to making a hot fire it is hard to beat tamarack, which is sometimes called larch or hackmatack. To my mind it is better than white birch and equal to yellow birch for a lasting fire, and a good deal hotter than either. The fact is that it is so hot it is apt to burn out the stove irons. You cannot find any better wood for foundation posts or fencing, since tamarack resists decay so well it lasts for years. A mighty useful tree in all ways.

During the summer the pipe lengths, greased with bacon fat to keep off rust, hang by wires from the roof, so the mice and squirrels can’t get at them. Once the critters make the jump from a rafter and skid off the greasy pipe they decide there are easier ways of getting their victuals. While I was putting up the pipe I found some of the chinking was loose between the logs high up on the east wall, so I yanked off the saplings that hold it in place and tucked in plenty of clay and then dry sphagnum moss.

Now that the nights are getting colder I have packed in the storage bin I built under the cabin floor all the provisions that would be damaged by freezing. The first one I made was a failure because it was built of boards and the mice got in, so I got myself an old oil drum from the abandoned mine, burned it out to clear away all smell of oil, and then painted it with tar on the outside so it wouldn’t rust. I set the drum in a box four feet square with a foot of sphagnum moss on the bottom and plenty of dry moss around the sides so that it is well insulated and if any mouse gets in there he will have to bring along a hacksaw. The lid is a piece of sheet iron and I reach into the box through a trap door in the floor. Potatoes and any other vegetables that I happen to get, as well as canned goods, keep perfectly in this little store bin. If I leave the cabin for a trip I have a heavy pad of sphagnum moss in an old bag that I put on top for insulation. When I am home the little amount of heat that leaks through the floor keeps it at just about the right temperature.

Another little job was to paint my weather vane which is the shape of a big pike. I relined the hole which fits over the nail on top of the pole with a small piece of metal tubing so that it will turn easily in the slightest breeze. I always enjoy watching the weather vane to keep track of wind direction. You can make weather vanes in all sorts of shapes, such as flying geese, arrows, guns, or a canoe with a man in the stern. Once after I had visited an old sea captain down on the coast I copied one he had made in the shape of a whale. It is easy to whittle one out, and to make sure that the vane minds the wind, put a metal washer under it so that it won’t rub on the top of the pole.

Mice have been troubling me lately. The critters got into my flour sack and I had to work fast, for once they break into your grub they send out word to all their friends and relatives to come on in and share alike. The way I stopped that was to make a water trap. All you need is a large can or pail and a sliver of wood which should be light and thin, about ten inches long and an inch wide. Find the place were it just balances on the rim of the pail and cut a small notch just back of that so the end outside the pail will be the heaviest. Then lean a piece of firewood against the pail so the critters can climb up. Balance the sliver of wood on the rim after tying a small piece of bacon on the end over the pail. It should then be set with the notch on the rim so that when your mouse walks out to get the bait the stick drops down and he slides into the pail. You can put water in it or leave it empty if you like, for most mice can’t climb out of a pail. However, be sure your stick is short enough so he cannot use it for a ladder and climb out if it falls in too. If you have balanced your sliver of wood just right it will swing back into catching position after it dumps each mouse. And, by the way, rub a piece of bacon on the stove wood and out along the trigger strip so the mice will follow the trail to the bait.

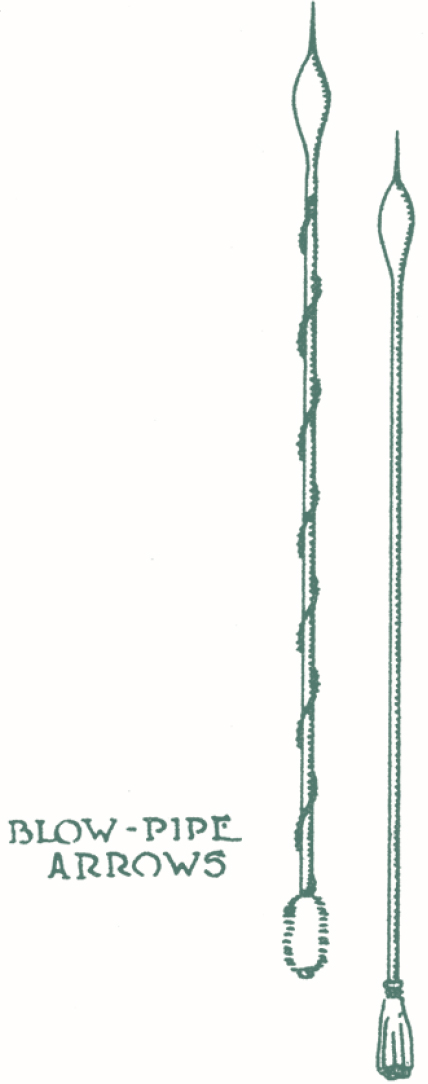

I must tell you about something interesting I tried after reading a story about South American Indians and how they use blowguns for hunting. I didn’t think much more about it until the Chief and I were poking around the old deserted mine when we went over after my oil drum. In what was left of the blacksmith shop I found a piece of quarter-inch brass pipe about four feet long. Well, that put an idea into my head so I took it home and started in making slender little arrows to see if I could make a blowpipe. For the arrows I used slivers of spruce with a small nail in the head to give them weight and a sharp point, and on the other end I wrapped a little strip of cloth until it was large enough to fit easily into the bore of the pipe. The idea of the cloth, which should be loosely wound, is that when you blow the air expands the end and makes a good seal to let your breath drive the arrow with force. I tried it out and the thing worked.

The arrows of the South American Indians range from twelve to twenty inches long and the shafts are very slender, some being no thicker than a match. They feather them with some kind of vegetable wool or even soft bark wound in a cone form just as I wound the cloth. The blowguns are from seven to nearly twelve feet long and some of them are lined with a bore made of a smooth reed. I have even heard that some of the Indians wind the shafts of their arrows with bark in spiral form to start the arrow rotating just as the rifling in a gun makes a bullet turn. Don’t think this is any toy, for those fellows down there can shoot accurately up to seventy yards. They even rig sights on their blowguns.

What I want to do when I get around to it is to make one of wood like the native guns. My brass blowpipe throws an arrow fifty feet and drives the point into a pine like nobody’s business. The way the Chief watched me made me pretty certain he will be doing the same. He always likes to try out something new.

We have had good hunting this fall and the Chief has a fine white-tailed buck hanging in the lean-to back of his cabin. Hank and I will also have venison before long to keep us going for some time. Once it gets cold and the meat freezes you can keep it all winter if you want to, and the longer it hangs the better venison tastes.

For waterfowl shooting we go down to Snow Goose Lake and I can tell you it is a beautiful sight to glide through the narrows and come out on the lake, blue against the gold and crimson forest, with an Indian summer haze to blend the colors. The air now is apt to be sharp even at midday, strong with the scent of dead leaves and swamp grass. Just as we came into open water we saw a bull moose standing on a little point that juts out from the tamarack swamp. He was one of the biggest we have seen for a long time and his antlers must have had a spread of at least sixty inches. I don’t believe there is anything so downright impressive as a moose in the open where you get a better idea of the size of the animal than when you come on him in heavy woods. He watched us for a minute and with a snort that sent jets of vapor from his nostrils he went off with that peculiar trot which takes a moose over the ground much faster than you realize.

The Chief’s favorite duck shooting ground is in the shallows where the wild rice and the water grass grow, and at one place where the water is only a few inches deep he will step out and twist a bunch of grass into the rough shape of a duck for a decoy. You wouldn’t think those tufts of grass would bring in the ducks, but they do.

The geese have been coming over strong lately, great flocks of them flying in wedge formation, and the Chief has spent a good deal of time down on Snow Goose laying in a supply of them as well as ducks which he smokes and puts away in a cool place for good eating later on.

This is the crazy season when some of the partridges seem to be out of their minds, flying wildly by day and even by night. Often they crash into trees or limbs, and even houses. What makes them lose all their cunning no one seems to know, but many a time I have seen them in spells of madness when they seemed to lose all fear of their natural enemies.

On one of our hunts we stopped on the way home and Hank brought in five partridges to make a fine Sunday meal for us. While he was working up the slope of a low ridge looking for birds he caught sight of a big black bear busy on a rotten log in search of grubs. The place was strewn with blowdowns and the trees, crossed this way and that at all angles, made some of the worst jackpots he had ever seen, so Hank couldn’t get close enough for a shot. Fat and well-fed for his winter sleep, he was, Hank said, and his fur was thick and purple-black. You can tell a lot about the health of an animal by the condition of the fur and when it is rich in color and shining you can be pretty sure the critter is in good health.

The way we like our grouse is to skin, clean, and bake them. I put the whole bird in a pan and lay very thin strips of bacon across the breast. In that way you baste the meat while it is cooking and it comes out moist and sweet. All you need then is salt and pepper and some hot biscuits. With ducks it is little different and Hank is certain he can cook them better than anybody else. A duck, he will tell you, must be picked, singed and then drawn and washed. Then you wipe it dry and tie the legs together, turning in the neck close to the breast. After that you season with salt and roast for about twenty-five minutes. The next step—and it is important—is to put a tablespoonful of cold water inside the duck, which keeps the juices from hardening. Anyone will tell you that a little currant or beach plum jelly to eat with the duck makes it perfect. Of course, as Hank says, there are plenty of fancy stuffings and basting with wine and such like, but if what you want is the taste of duck, that is the way to get it.

On the way home the day we got the partridges we struck back into the woods to look over a little brook that we had not visited for two years. The place was so changed we hardly knew it, for the beavers had been busy and instead of a brook we found a good-sized pond held by as fine a dam as you could find. The beavers are busy now getting in their Winter food supply and all about back from the pond on higher ground the young poplars have been neatly cut and dragged to the water. While we were watching, a beaver came out on the far end of the pond and started swimming down with a newly cut length of sapling. The instant he saw us there was a quick, hard splash and only the widening rings on the water showed where he had been. It is not often you see them by day, for they do most of their work after dark.

With young Tripper to take his place in harness this winter, I have made myself a new sled which is a little different from the kind we usually have up here. Instead of runners made of split ash, I used two old hickory skis that a fellow left here a year ago. My idea is that the extra width of the skis will keep the sled from sinking as deep into the snow as it does with the narrower runners. The skies are a shade heavier than the regular runners, but I allowed for that by lightening up on the rest of the sled so it weighs just about the same as the old one. The new sled is just six feet long, which is small, but plenty for two dogs. I never believe in overloading them.

Old Wolf loves a sled and all the time I was building the new one he was nosing around inspecting my work and trying to show me he liked it. When I got out the harness to make sure it was in good order he just about went wild. That’s the kind of sled dog you like to have.

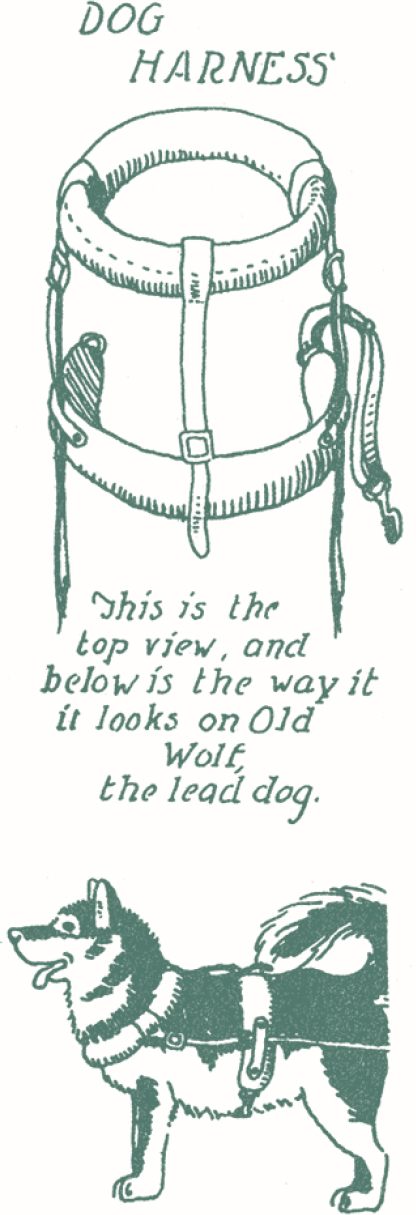

Tripper has been doing fine in his training. The harness I use has a round collar made of moose hide and filled tight with pieces of old blanket, wrapped around heavy wire to stiffen it. The collar has a strap on each side to snap onto the traces, and one on top fastened to the cinch strap. Now Tripper steps right along behind Wolf and pulls his share like a good one. He has learned to stop when I shout “Whoa,” and puts his shoulder to the load when I give the command, “Mush!” One thing you have to remember is not to overwork a young dog. At first you carry no load on the sled and you have to be careful not to let it run up on the dog and hurt him. Patience and more patience and firm kindness is the secret of training a dog, or any animal for that matter. You want him to love his work and good sled dogs do.

The beavers are busy getting in their winter food supply

After a training trip I always give the young dog a little piece of meat as a reward, but that is only during schooling. Experienced sled dogs work best when they are fed at the end of the day, but when a puppy is young he needs food three times a day. If you want a good sled dog don’t make a pet of him. You can be good friends, but a dog that is a pet is almost sure to be spoiled and does not obey as he ought to. You must earn a dog’s respect and he has to know who is master.

The Chief and I have been dressing the skin of his first buck which will make fine moccasins later on, although he wants to get a moose, too, for its hide will stand more wear. His method of making buckskin is the one the Indians have used for generations and it is fairly simple.

A lot of hard work goes into making a good skin, for the only skin worth having is one that is soft and will stay soft even after it has been soaked time after time. To begin with, the Chief mixes about two quarts of wood ashes in half a wash tub of warm water and puts the skin in to soak so that the hair can be scraped off easily. This can usually be done after the hide has soaked two or three days.

To scrape off the hair, hang the skin over a log set up at an angle to make it easy to work on, and scrape with an iron tool with the edge ground flat. The one the Chief uses is made of a piece of bucksaw blade set in a slotted handle, and it works fine. An old flat file makes a good tool.

When all the hair has been removed and the top layer of skin cleaned off, turn the hide over and start what is called “fleshing” it, which is the job of scraping off every trace of flesh and fat that was left on the hide when it was pulled off the animal. This is hard work and you can save yourself many a backache if you have your fleshing log at the right height so that you can put your full weight on the scraping tool as you push it down and away from you.

When all the hair is off and the skin has been thoroughly fleshed it ought to be rinsed in clear warm water and then wrung out. It is a pretty awkward job to wring out a wet deerskin so the Chief and I rigged up a crude sort of wringer made of two short lengths of spruce logs with a handle on one, and set in a frame. It does a pretty good job too.

When you have all the water out of the hide the job of tanning begins. This is something that ought to be prepared for in advance. The Chief saves the brains of the deer, dries them very slowly in a pan at the back of his stove so they won’t cook, and when they are dry he puts them in an old sugar bag and boils them slowly until they are soft. When the boiled brains have cooled off so that he can stand to put his hand in the mixture, he pours them in the wash tub and adds just enough water so that the hide can be thoroughly soaked in the mixture where it must stay until the skin is just as soft as an old glove. In place of brains you can use common brown kitchen soap which is melted up until you can make a rich solution. Homemade soap, the kind made with lye in it, is even better, but the Chief never uses anything but brains.

While the skin is soaking it should be thoroughly worked every once in a while to help soften it, and after it has been soaking for a few hours take it out and pull it in every direction with all your strength to make the fibers pliable. This process of pulling and working dries the hide, and if it is then still stiff put it back to soak and repeat the process.

When the skin is properly done you should be able to squeeze water through it. The real secret of making good buckskin is to work it by kneading and stretching it until it is thoroughly softened. There is no easy way and it is safe to say that you can hardly work a skin too much.

The final drying should be done by squeezing all moisture out in the wringer and then working and pulling the hide until it is dry and smooth. The final step which keeps the skin soft even after it has been wet through use is smoking for several days in the same kind of smoke that you use for curing meat. It is important that as little heat as possible reaches the skin. To get an even smoke the skin should be turned over from time to time and the job is done when the hide has taken on a beautiful soft yellow tone. When the hide is used for moccasins some folks give one side a dressing of neat’s-foot oil.

On my cabin floor is a fine bearskin rug which the Chief, Hank, and I tanned. Where you want to keep the fur you don’t soak the skin in water and ashes, but after fleshing it stretch the hide by lacing it on a frame in a place where it will be sheltered from rain. Then you paint on a coat of the brains mixture made just as you do for buckskin. Several coats should be applied at intervals, between which the skin should be pulled and worked thoroughly to soften it. I remember we laid it out where the pine needles were thick, fur side down, and beat it with saplings to help soften the fibers. After it was thoroughly softened we gave the fur a good washing in the lake, stretched and worked it until it was dry, and then smoked it for several days. The hide is just as soft now as the day we finished the job, and mighty comforting to the feet on a cold morning, not to mention being downright good looking.

While we were working on the deerskin we got talking about the way we used pyrite to start our campfire and other methods, such as whirling a stick with a bow which is difficult, and using a magnifying glass, a fine method when the sun is out. But one of the best fire makers I have ever seen is the fire piston which they say was invented ages ago and is still used by primitive natives on small islands in the faraway Pacific. They make their fire pistons of wood, but try as I could, I never made one of wood that would work, although I’m going to try it again one of these days. But I did make one of a short piece of quarter-inch brass pipe that does a good job.

The fire piston works on the principle that air gets very hot when compressed under high pressure. Anybody who has ever worked a bicycle pump will recall how hot it gets when you pump it for a while. Well, the fire piston works that way only you take just one stroke to compress the air which may reach a temperature of more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

The secret of making a piston is to have a small, smooth bore cylinder, one end of which is closed, and a plunger with packing on the end that allows no air to get by it when it is thrust quickly into the cylinder. The end of the plunger is hollowed out to a depth of not more than one-eighth of an inch and in this little hole, which should be wider at the bottom than at the top, put a little wad of tinder. I have used charred cotton rag and also finely shredded cedar bark, but it has to be thoroughly dry.

To start your tinder glowing you pull the piston almost out of the tube, put the end against something solid like a tree or a wall and give a quick thrust. The speed and force of the thrust has a lot to do with getting your tinder lighted, and in case you try it I want to tell you that it takes patience and practice, and don’t be disappointed if the first piston doesn’t work. I should also mention that the plunger must reach to within three-sixteenths of an inch of the bottom so that you get high compression.

I made my plunger out of a nail cut off square with a groove one-fourth of an inch wide filed as close to the bottom end as I could make it for winding on thread for packing. I also took care to sandpaper the nail very smooth so that it would travel freely and on top of that the packing should be greased. I found that a little candle wax mixed with bacon fat worked well. The natives of the Pacific have a belief that a fire piston will work only if it is greased with dog fat, but I love my dogs too well to go that far.

On the top end of the piston I fastened a wooden handle of a kind that you can grasp between your fingers and thrust hard with the palm of your hand. I have made several designs for wooden ones and sometime I am going to see what I can do. To my way of thinking the wood should be very hard so that after use you get a fine glassy finish in the bore.

In the long winter nights when we three get together we sometimes make miniature models of cabins and the like, using flat weathered rocks or a weathered slab of silvery dry-ki.

Hank made a model of his cabin and even put in little trees made of dry green moss, the kind you find growing in thick woods away from the water. This moss grows in the natural form of beautiful little trees and is just right for our purpose. The Chief whittles out beautiful models of canoes and also makes some of birch bark. One of his models showed an Indian tepee set up on thirteen poles as the Indians used to do, each pole representing one of the moons of the year. He set it on a flat rock that looked just like a little island. There was a canoe on the shore and a little fleshing beam, a place for a fire, and a hunting shed on a little staging just as it would be stored during the summer. He has an idea that he will make a winter scene sometime by putting a thin coat of glue on a rock and covering it with salt to look like snow. And of course you could use cotton batting.

As for myself, I once made a miniature logging camp complete with hovels, bunkhouses and cookhouse, logging sleds loaded with little logs held together by chains, and even tiny peaveys, as well as a bateau six inches long. But that wasn’t all. I finished it up by carving two horses to go with one of the sleds and a teamster two inches high standing alongside. It was mighty good looking if I do say so.