Thundering lce and Black Water

THE BREAK-UP has come and the ice is out of Cache Lake! It started early one morning and when I woke up and heard a muffled rumbling sound coming through the darkness from the head of the lake I knew what it meant. There is no mistaking the thunder of ice going out. Chief Tibeash and Hank heard it, too, and when they came over we went up to the carry to watch the sight that next to the geese coming north means more to us than anything else that happens in early spring.

Just above the rapids where Lost Chief Stream gets into the Manitoupeepagee River, the ice jammed on the rocks and the water flooded over the banks and rushed down through the woods in a frothing torrent that kept us up on the ridge. It was not long, though, before the jam broke and great blocks of ice, some as big as a wagon bed, came thundering down the main stream. You wouldn’t know there were any rapids then, just tossing gray ice riding water black and cold and powerful.

The ice on the rivers never freezes as thick as on the lakes, where the water is quiet, so it is the first to go out. Sun and warm south winds and the battering of the ice coming down the streams are needed to start the heavy stuff out of the lakes. By sundown that day the ice at the head of Cache Lake was beginning to heave and break.

I never have quite understood it, but the news of the ice going out of a river spreads like no other information in the woods. Once I was at a settlement when an Indian came in and told us that that morning the ice had started out of the mouth of the river which was two hundred miles away. I asked him how he knew and he just shrugged and said, “I know!” I made a note of that date and found later that it had gone out on the very morning he had told us.

I knew it wouldn’t be long after the ice went out until the geese would be coming over. And sure enough, I heard them! The night was still and clear, the stars were sparkling like splintered crystal, and the cool white moon was loafing high over Snow Goose Lake when it came—that wonderful sound all men of the woods wait for every year—the hoarse honking of the big gray Canada geese. In clear weather they often fly right through the night and just hearing them talking among themselves up there in the friendly darkness does me a world of good. You can be sure there was a wise old gander at the point of that great flight wedge leading them on to the lonely salt marshes that stretch along the low shores of James Bay.

Although the ice has gone out and signs of spring are multiplying, there is still plenty of snow back in the woods where the sun can’t reach it. It is no longer the soft white coat of winter, for now it is gray and heavy. Under the conifers, where the partridges, grosbeaks, siskins, and crossbills have been feeding, the drifts are sprinkled with the brown scales of cones and tiny chips of bark, twigs, and broken buds. But, unlike the dirty snow of city streets, mixed with soot and cinders and the sodden refuse of civilization, our snow is clean. If you dig down in the shadow close to the north side of a big tree you find the snow still dry and granular, which is one way the Indians know the direction of north in winter storms.

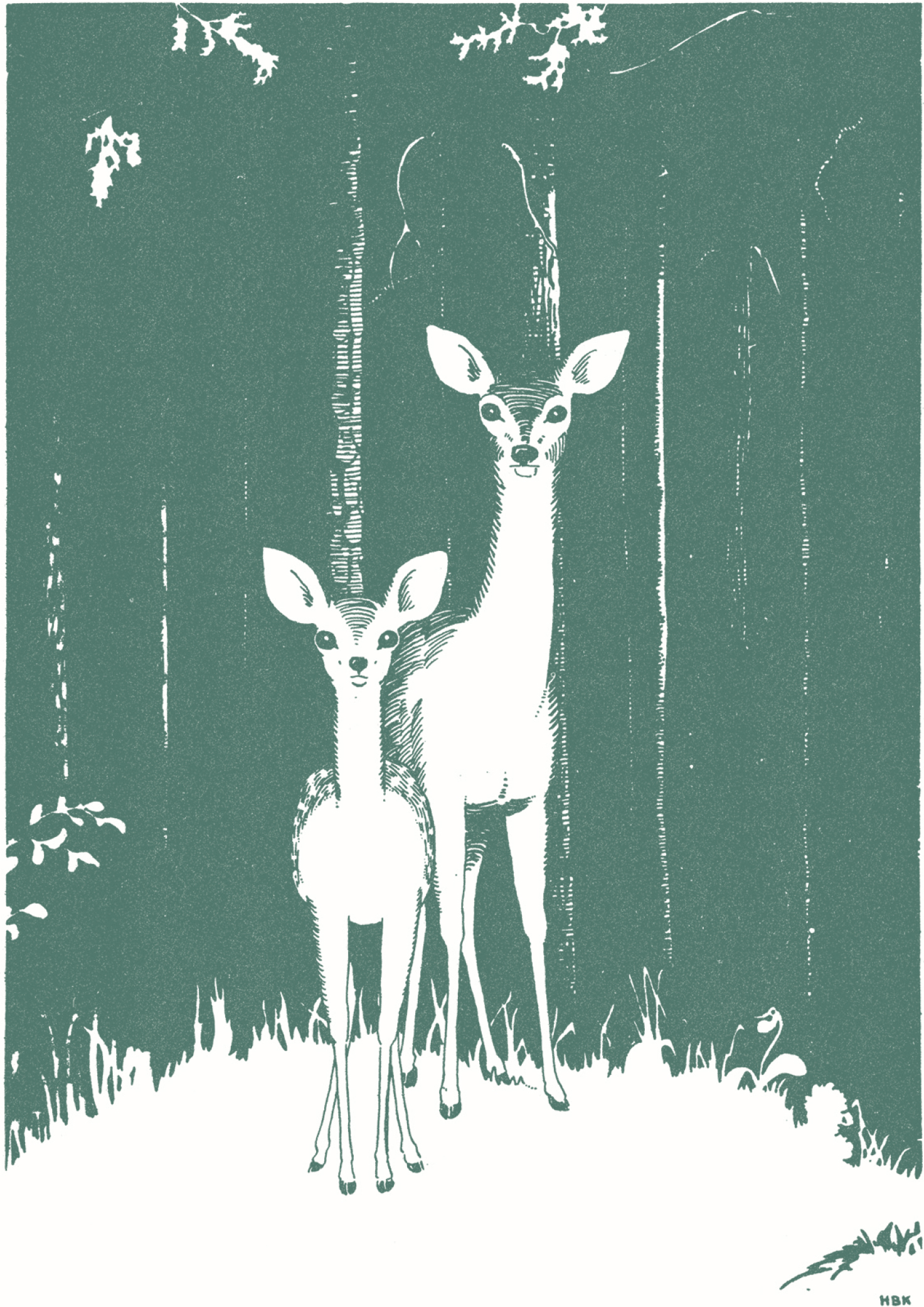

Down in the little marshy place by the spring the first green and purple hoods of the skunk cabbage are showing. After looking at snow since last November, they are beautiful to me. I walked along the shore of the lake and saw deer and moose tracks in the soft earth near the narrows. That’s where they swim across in their travels back and forth between the ridges in the summer.

That great flight wedge leading to the lonely salt marshes

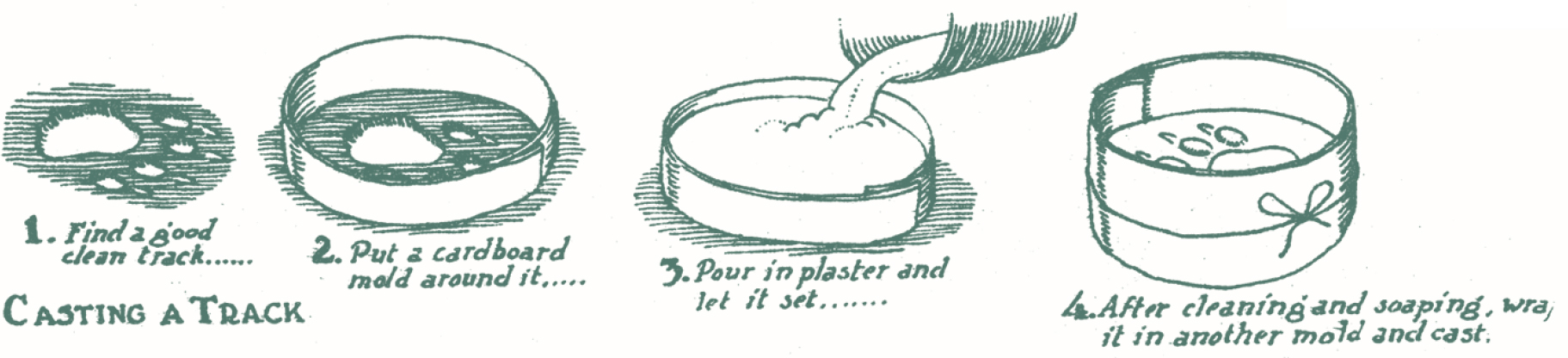

The sight of fresh tracks started me thinking of the days when I first came up here and got a lot of fun making casts of the tracks of wild animals. It is the best way to study and learn to know their footprints. Spring is a good time to make casts, for the ground is wet and makes nice clear prints, especially if you can find them in clay. All you need is some plaster of Paris mixed about as thick as heavy cream. The right way to mix it is to put cold water in a tin can and then slowly sprinkle in the plaster until the water disappears and it looks like cream. Start by making a little fence of cardboard around a track, pushing it into the mud carefully. Then pour the plaster in very gently and leave it alone for half an hour or so. Don’t try lifting it before it sets hard. Take it home and let it dry out. Then unwrap the cardboard, wash off the mud, and you’ll have an exact pattern of the animal’s track.

The next step is to make a cast from the pattern, for what you are really after is a track just as the animal left it in the earth. First you coat the pattern with soap softened in hot water. Now wrap another piece of cardboard around it, first soaping the inside wall, and then pour in the plaster. Be sure to let it dry for several hours. Finally unwrap the cardboard, separate the casts, and there is the finished footprint.

With a little practice you can make fine prints and start a collection. If you want to try something special you can lay out some soft mud or clay at night with some bait in the center. You ought to have tracks by morning. For practice you can begin with a cat or dog.

While you are out looking for tracks you will see many other things of interest. Soon I’ll start looking for the marsh marigold with blossoms the color of country butter, and the first violets too. I seldom pick wild flowers for I would rather see them blooming just where they grow. There would be lots more mayflowers and lady’s-slippers if people had not pulled them up by the roots until they are seen in only a few places now. Another pretty flower, although its perfume isn’t so pleasant, is the wake-robin. Trillium is another name for it.

Watch for the white flowers of the bloodroot that fold up at night, and the hepatica with its beautiful pale blue, pinkish or white blossoms. Learn to enjoy your flowers where they are. Picking wild flowers makes me think of kidnaping—taking them away from their natural homes and all the things they need from the earth. Generally the flowers that come in April are small, growing close to the earth as if to be ready to duck back in if it gets too cold. Later on when the weather is warm they grow taller.

When I was a boy I loved to wander along the brooks and streams where life is very active in the spring. Some of the fish are spawning and the turtles are sure to be out sunning themselves on logs and rocks on warm days. The snakes are also moving about. In truth, very few snakes are poisonous, and there are none of that kind up here. I never kill snakes for they help in keeping down the mice and other rodents that damage our garden and get in the house.

There is plenty of life in the woods now, although you do not see much unless you know just where to look. The young skunks are in their burrows and the squirrels are busy tending to their new families. So are the mink, which make homes for their little fellows in hollow logs. There are not as many otter up here as there used to be, but there are still some. They keep their babies in well-hidden places under banks or roots. The lynx are also busy with family cares. Their kittens mew just like the household kind and are just as playful.

With the first stretch of warm days in April the eggs of some of the hardy insects begin to hatch and you soon hear them humming around in the quiet of the twilight hours. The beetles and the bark-borers begin to appear now, and little mounds of soil show that the hard-working ants are busy. If you watch you will notice quite a few moths and butterflies about, but they are mostly the small dull-colored kind. The beautiful large butterflies won’t be seen until the weather is much warmer. I have already seen a queen yellowjacket flying around under the eaves of the cabin. She is looking for a place to start a nest, I expect. Later this month the bumblebee queen will be doing the same thing. You usually see her fly close to the ground watching for a likely spot for a nest, which may be in an old mouse nest or in a hole in the ground. I have already seen a ladybird beetle—the little red fellow with black spots on his back—walking across the sill of the window after his long winter sleep.

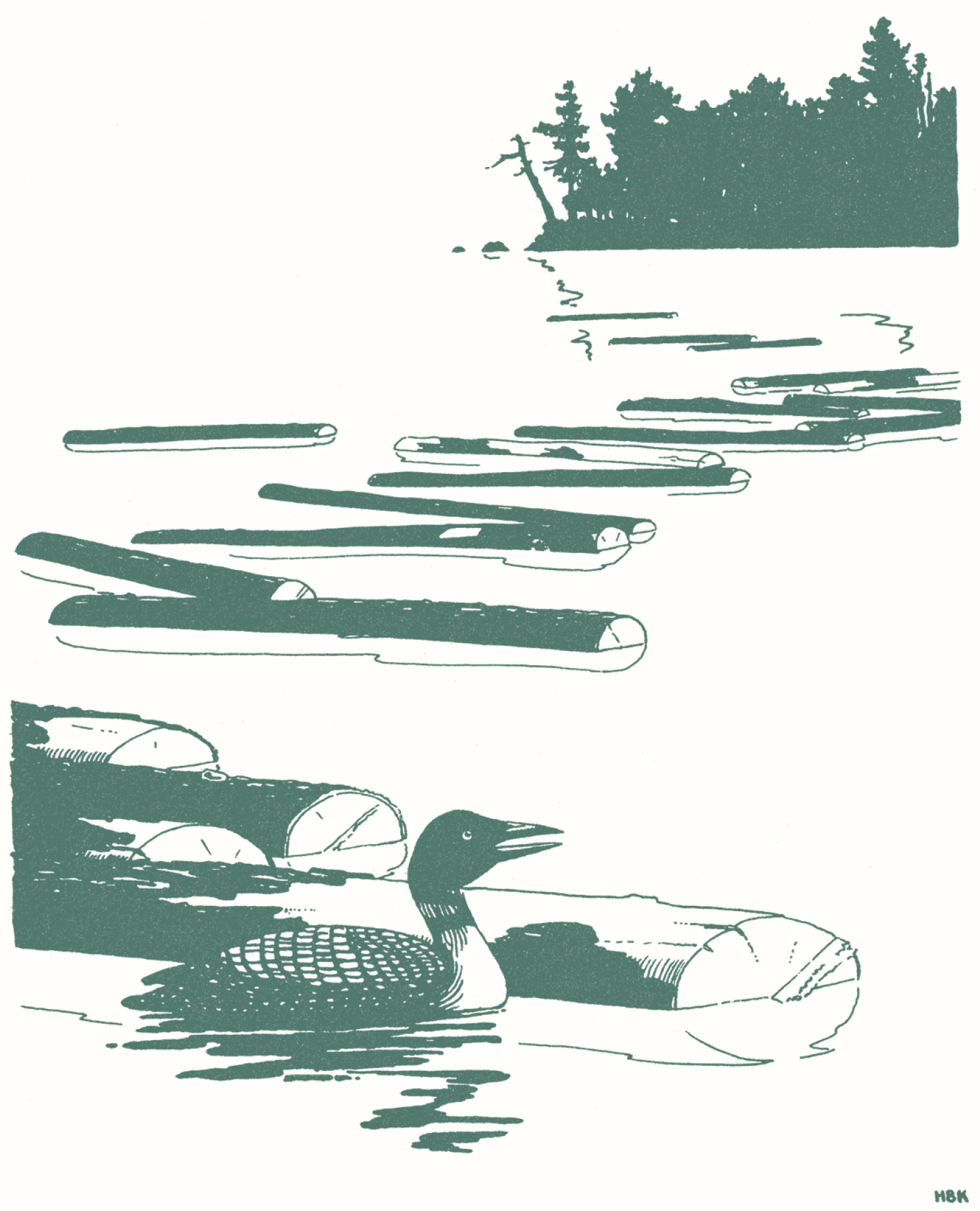

Back in the days when they cut big timber up here, the river crews had to wait for the lake ice to clear before the spring log drive could begin. Once it started no power on earth could stop that wild trip of the big logs down the streams into the rivers, across lakes, over falls, and through rocky gorges to the sawmills many miles away. Not so much of that now and much of it is pulp logs too light to keep up a muskrat.

I can look back to the days when the rivermen rode logs two feet or more across the butt. You could hear the logs coming for miles, for when they formed jams, which was often, there was excitement aplenty and more than any man’s share of danger or death. Those big sticks would toss around like straws in a wind and pile up in a tangle the like of which I can’t describe. Breaking jams was risky work.

Right up above the carry I have seen men out under the downstream wall of a jam looking for the key log that held back thousands of tons of timber. Working with peaveys and pike poles, they always found it. Once the piece was loosened the jam broke with a rush of flying sticks, and every man raced for his life. If there was clear water and no logs between them and the river banks, they had to run ahead of the breaking jam. Sure-footed as cats, they leaped from one log to another until the jam had settled and spread out on the stream. Then if the water ahead was steady going they rode the logs as long as they were running free.

Come what might, I never saw a riverman who wasn’t ready to go out on the logs when the cry, “She’s a-holdin’ ” or “She’s a-jammin’,” went up. They would race out and try to break away the logs before they built up to a real jam. Some died doing it, but thought of going over the Long Portage never held them back. No place for a timid heart or a weak back.

When peaveys and poles failed to break the jam they would dynamite it. Usually somebody on the bank would throw a stick of explosive fifty feet or so across open water and the boss standing among the logs would catch it. He would tie the dynamite to the end of a long pole, light the fuse and poke it down in the tangle of timber, and shout, “Fire! Fire!” Every mother’s son would hike for the bank and wait behind trees and rocks for the blast that hurled logs hefting a ton or more high in the air in a cloud of white smoke and flying spray.

Once the logs began to move, the crew rushed out on the river yelling, “Now she hauls!” or “There she pulls!” and “Walk her! Back on her, boys!” Night and day as long as the drive was on every man was wet through. They would stand in the ice-cold water up to the waist pushing logs into the current, yet seldom did I ever hear of anyone being sick. What they wore for underwear was heavy wool, which is what you want for wet work.

Speaking of blasting jams, I remember the time I had been at one lumber camp for over a week before I found out that what the boss pulled out of a box under my bunk every morning was the day’s supply of dynamite. And me a steady smoker!

Looking back on it I believe my best memory of the great river drives is the picture of thousands of logs lying motionless in the dead water below the rapids on a warm May evening. At that time of day when the breeze dropped, the sweet smell of rock-scarred pine and spruce came strong and fresh through the thin mist that gathered almost as soon as the sun got off the water. Then the men would stop to eat, and in the quiet you would hear whip-poor-wills calling or maybe an owl back in the darkening woods. Good days, they were.

Lying motionless in the dead water

Taking logs through fast water was only part of the drive, for booms had to be stretched across bays and coves to keep the timber on its course, and on the big lakes the logs were gathered in “bag-booms,” big loops made of logs chained end to end, and towed by small steamboats or pushed by a favoring wind to the outlet stream. And all the while men in “pointers” or bateaux, big boats with high pointed ends, moved about picking up drivers, working logs off the rocks, or breaking up “wings” which formed when a bunch of logs took a notion to start off by themselves. And the rear crews, “sackers” they called them, followed the main drive, clearing logs off the banks and shallow places.

Life in the lumber camps was simple. The food was plentiful and good or the men left. They were pretty sure to get corned beef and salt codfish, sometimes tripe and plenty of baked beans with pork, dried apples stewed, molasses, fruit preserves and cookies, cake and pie. Any cook who couldn’t turn out good hot biscuits and all the pies the men could eat was in for trouble, which meant the tote road for him.

When the drive started, the cookees—fellows who helped the cook and waited on table—followed the crews, serving four meals a day. They got thick pea soup, beans, ginger cookies and sweet cake always, and tea strong enough to float an axe. Some of the cooks were pretty fussy in camp and made the men take off their hats, wash their hands, and slick their hair before sitting down on the benches at long board tables piled with victuals. Meals were eaten in silence, a rule that headed off arguments that might end with flying fists and feet. Using feet in a fight was fair and square in a lumber camp battle, and many a man’s face showed the punctures of the calks in some other man’s boots.

Almost every camp had a cat. No one seemed to know where it came from, but I can tell you an old-time logging cat was as independent as a pig on ice and lived the life of Riley. It helped to keep wood mice out of the oatmeal barrel, which was where it often slept. I heard of one cat that would follow the spring drive with the cook’s outfit and at the end travel back to camp to live wild until the crew came in to start cutting at the end of summer. Another cat I knew always took a seat on the first load when the contracting teamster started hauling supplies to the camps in September. Yes, those tote road cats lived well, and gave the camps a homelike touch.

Every time I think of cats I recall a story old Billy McDonald used to tell. He was foreman at my father’s camps and a rare storyteller. Often when the men were sitting around the big drum stove drying their clothes, someone would prime Billy to start a yarn. One of his best was about a famous camp cat. It seems that the old-timers in the logging camps would tell the green hands stories of strange and terrible doings in the woods, and sometimes the talk would work around to the devil and his visits to lonely camps. Usually they were tales of Paul Bunyan flavor but altered to suit the occasion. Billy told about one cold January night when Lucifer appeared and demanded a man. The old-timers played up to that and there was an awful goings on over which one of the new men would be given to the devil to carry away. Finally when they’d had their fun somebody grabbed the camp cat, a black one, tossed it to Satan and told him to hit the trail. Nobody said a word except a man by the name of Victor who leaped toward the door and tried to save the cat, but the devil disappeared into the stormy darkness with the feline yowling like a banshee. Then the men broke down and howled themselves hoarse.

Billy didn’t remember exactly what time it was, but he thought it was about three o’clock in the morning when there was a strange noise at the door. The cook, who was turning out to start breakfast, opened the door and let out a yell that brought all the men out of their bunks. What they saw froze them where they stood. Coming through the door was a black cat, the very same they had thrown to the Evil One, but now it was as big as a bear. Its eyes were burning red, and its tail, as big as a man’s arm, was waving savagely. The beast went from one man to another. sniffing and growling, and you could hear them sucking in their breath with terror. Then the cat walked over to Victor and began purring—Billy said it was as loud as a donkey engine. It seemed to be trying to get him to follow, so Victor got together his outfit, picked up his rifle, and the cat led him away into the dark woods. Nobody moved or said a word.

Weeks went by, but no sign or word of Victor and for reasons of their own the logging people made no attempt to find him. Then late one Saturday he turned up looking well-fed and satisfied. The whole camp ran out to meet him and rushed right back when they saw Victor riding a sled load of fine furs pulled by the huge black cat. As soon as the animal saw them it began to spit and snarl, and they hit the bunkhouse doors like a log jam.

Everybody treated Victor with great respect and some of the men even took off their hats when he came in. He told them he and the cat were living in an abandoned trapper’s cabin on Wolverine Lake and that he was on his way to the settlement to sell his furs. As Billy told it, Victor said that after he went away with the cat that night, it led him straight to the trapping cabin. Then after he had set things to rights and got a fire going the cat went out. Daybreak was a long time coming and Victor was beginning to get worried, when finally away off to the west he heard something and soon he saw a bull moose coming toward him on the tear with the big black cat riding him. Yes, sir, that cat was cradled snug-like between his antlers and it was holding the animal’s ears with its paws just like he was driving a horse. He brought the moose right to the door and then jumped off so Victor could shoot it.

That was just the beginning, for from then on the giant feline went hunting everyday and brought back prime fur animals. All Victor had to do was to sit in the cabin and work on the skins of martin, fisher, mink, and lynx, which the cat brought in slung over his shoulder as proud as could be. Once it came back with a full-grown wolf and another time it dug a bear out of his wash and drove him right to the cabin.

According to Billy, there wasn’t much truck with the devil around the camp the rest of that winter. Victor, so the story goes, got rich with the aid of the big cat, married, and settled down on the west branch of the Shinkwak River, taking teaming contracts once in a while just for the fun of it, the cat riding beside him and purring all the time.

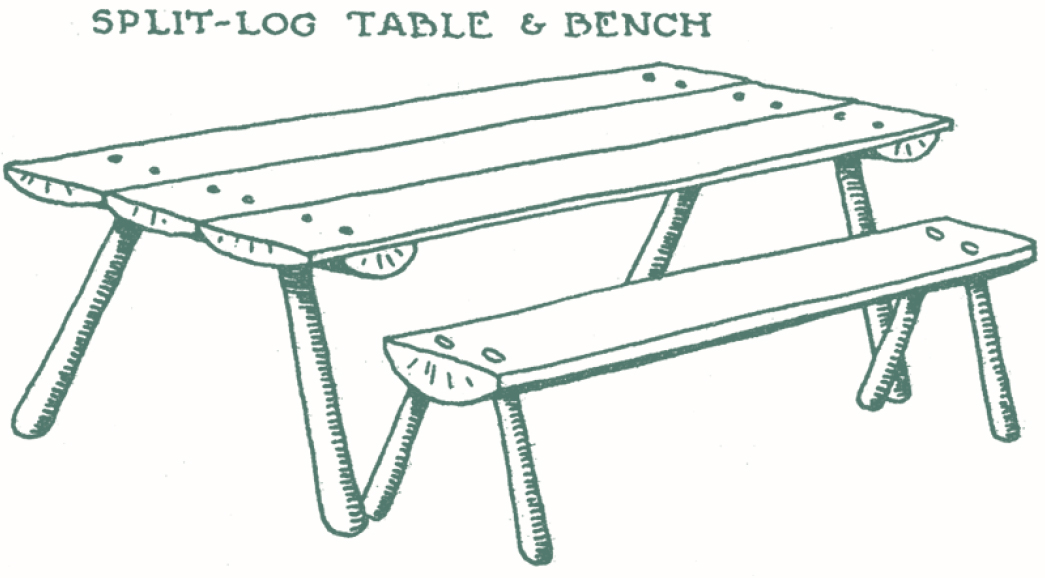

During the usual April rainy spell I put in some time getting things fixed up for the summer. I made myself a new table from three boards, two pieces of split birch log, and some seasoned birch saplings for legs. I plan to make some benches the same way to go with it. That will mean company won’t have to sit on the nail keg. The only tricky part is to bore the holes in the logs at the proper angle so that the legs will set just right. The best way is to lay the pieces on the floor, make a wooden templet or guide of the angle, and use it to start each hole.

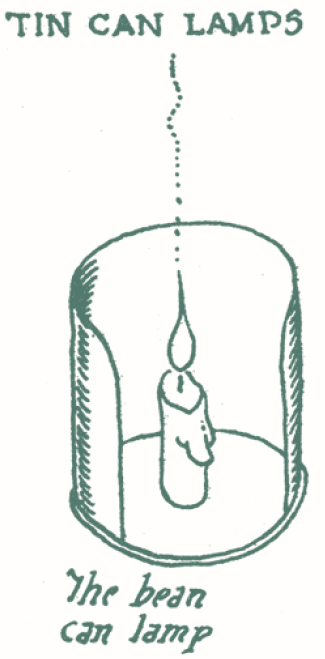

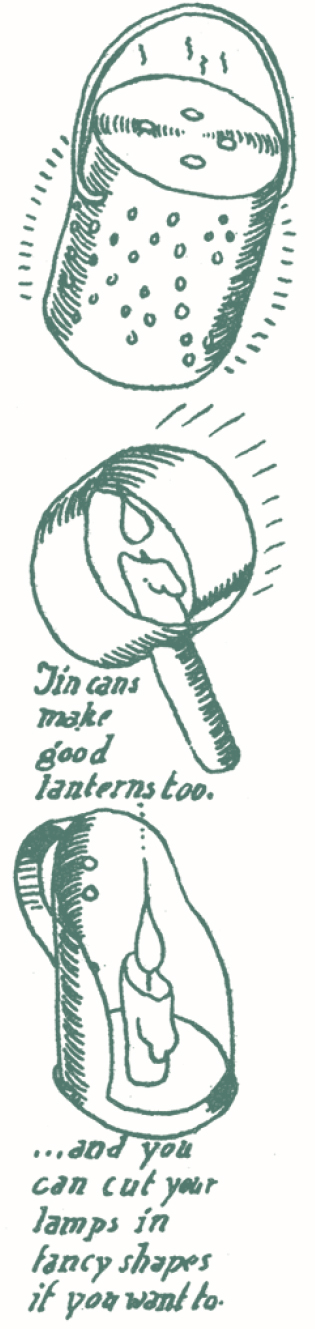

While I was working on the bench Hank came over and got an idea that he would try his hand at making some candle holders out of tin cans. You’ve probably seen some of them before. They come in handy and a candle is a pretty safe light to have in a house, especially if you have to carry it around at night, which is not safe to do with a kerosene lamp. What is more, a candle is almost certain to go out if it drops on the floor. I save the ends of all burned candles, melt them up and pour them into a jelly glass, first setting a wick of string in the glass by tying the top to a twig that rests on the rim of the glass. This kind of candle lasts a long time.

Hank sometimes makes his own candles by molding them in the bark slipped off a small decayed birch sapling. You often see birch rotting on the ground in dark places in the woods and if it has been there long enough the soft wood can be pushed out, leaving a nice mold for a candle. You make a little wooden plug with a hole in the center to hold the wick in place. Stick the plug in the bottom of the birch tube, tighten up on the string, and tie it to a twig across the top. Then all you have to do is pour in your melted wax and when it’s hard run a sharp knife down the side and strip off the bark. A piece of bark about hoe-handle thick and four inches long is easy to clean out and makes a candle of the right size.

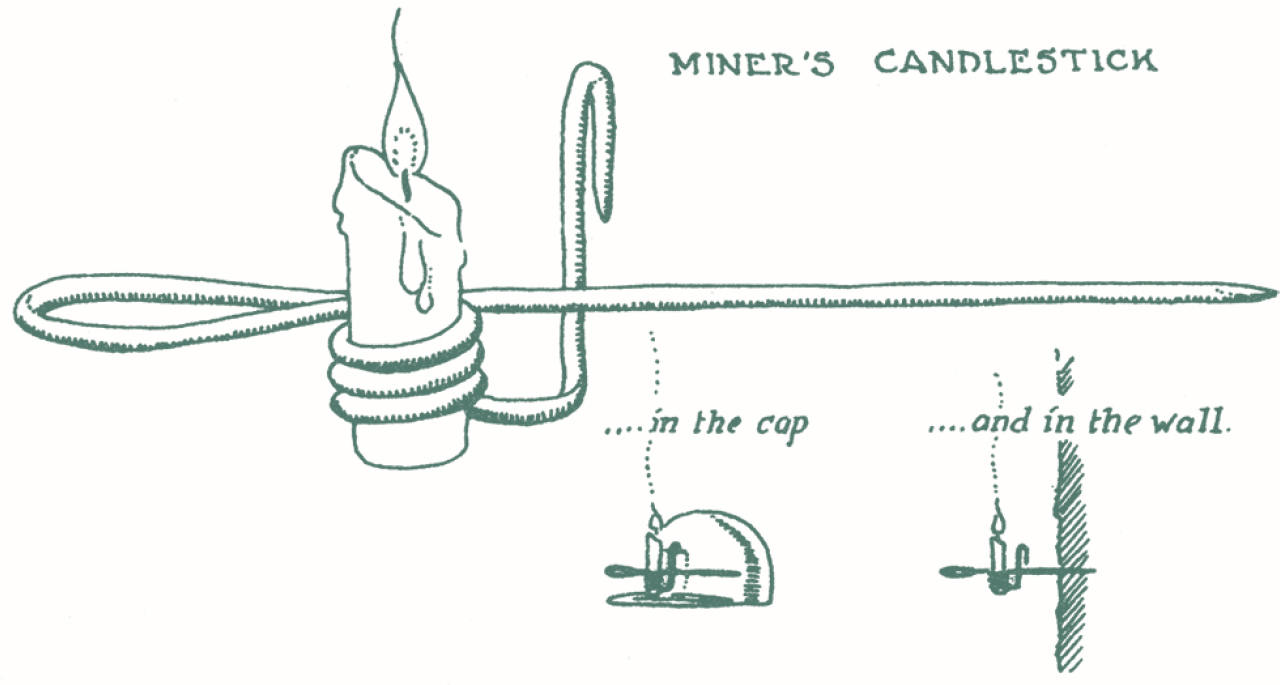

When I first came up to this country I worked for a while in a mine and I still have my miner’s candlestick and a very handy thing it is. One end is sharpened so that I can stick it into a wall, and there is also a little hook to hang it on my hatband leaving my hands free to work. They are not used much since the gas lamps came in, but I find it useful and it keeps the memories of my mining days green.

For a long time I had been wanting a bellows to quicken up my fire once in a while. It is a very handy thing to have around for various purposes. So during a stormy spell I got to work and made one. Mine has extra long handles so that I don’t have to stoop when I use it.

The main part of the fellows forming the air chamber is eight inches wide by twelve inches long and the handles are two feet long. I had saved a nice piece of pine board which I planed down to half an inch thick so the bellows would be light to handle. For the nozzle I used an old .38-55 rifle cartridge with the head filed off. It is just about the right size, the wide end being fitted into the block at the point of the bellows.

In the lower board I bored an inch and a quarter hole for the intake valve. The valve flap is made of a small block of wood faced with a piece of soft leather about a quarter of an inch larger than the hole with room enough left on one side to tack it to the inside of the board. Across the block is tacked loosely another little strip of leather, so that the flap can rise about a quarter of an inch. The idea is that when the boards are pulled apart, air is sucked in, but when they are pushed together the air forces the leather flap tight against the intake hole.

On the bottom board is nailed a little block about two inches long with a hole bored through it to hold the nozzle. Now, before you hinge the top board to the block with a strong piece of leather, you have to put springs between the boards to keep them separated. I used two slender pieces of willow, curving them around and tacking the ends down to the lower board near the point of the bellows. With that done you are ready to hinge the top board and fit the leather sides. For this you will need some soft pliable leather. I used soft smoked deerskin, but the sheepskin chamois that you can buy would work very well. To get the shape of your leather the best thing to do is to prop the two boards apart where you figure they would be as wide open as you would want them, and then fit a paper pattern around them and trim it until it is just right, leaving plenty of room at the pointed end for tacking around the block.

By using a pattern you don’t run the danger of spoiling your leather, for the job of fitting is a little tricky. I found that the best way is to tack the leather on with the tacks part way in until you are sure it fits, expecially around the handles where you have to notch it. When it is all laid on you can drive the tacks home and then cover the edges with a binding strip of rawhide which not only protects the leather but helps keep it airtight. There should also be a binding strip where the leather fits around the point of the bellows.

Aside from brightening up my fire in no time at all, I use the bellows when I ready up my house to blow dust and crumbs out of the floor cracks where it’s hard to get at them with the kind of home-made broom I make.

A while back the Chief told me about a fine litter of husky pups owned by an Indian who lives on Otter Stream, so I went up to look them over and brought one back, for old Wolf needs help on the sled and by next winter the young one should be able to pull his weight. Being given to barter when the trading is right, I took along an extra bucksaw and after some palavering back and forth, and with a plug of tobacco thrown in, I got the puppy. He’s a smart little fellow with a black cap, ears and back. The rest of him is almost white.

He seems to like his new home and it took me only a few days to name him. Every time I moved he would pounce at my feet to grab my shoelaces or the bottom of my pants. I tripped over him so much I said suddenly one morning, “Young fellow, your name is Tripper!” That’s a good name because he’ll soon tire of tripping me and when he grows up and is a fine sled dog he will be taking many trips.

Tripper is about the size of a ground hog now and has all the signs of the true husky. His fluffy little tail curls close over his back and when his pointed ears stand up to listen hard he looks like a small wolf. I’ve got to thin him down because he’s too fat now. It’s comical to see him try to chase my tame deer mouse. Once he tripped over a root and fell head over apple cart, sat up looking sort of foolish and then started trailing the mouse again.

Old Wolf doesn’t quite know what to make of the young one, but he is patient when the pup pulls his tail, gnaws his ears, and tries to chew off his feet. Just once Wolf growled and Tripper, knowing what that meant, ambled off to play with a piece of deer horn I gave him. He gnaws on that horn by the hour, which is fine for his teeth.

In the fall I’ll begin training the pup for his job as a sled dog. You never break them to the sled until they are six months old and strong. Before that age you can ruin their strength and spirit. About midsummer I’ll make him a simple deerskin harness and let him play around pulling a little piece of spruce sapling weighing just a few ounces. That will make it easier for him to get used to the feel of the regular harness when he takes his place behind Wolf. And Wolf will not let him forget who is the leader and the boss, and Tripper, being next the sled, will have to learn the wheel dog’s special job.

I am certain to have a spell of seed-catalogue fever which generally comes on without warning at the end of one of those April days when the air is soft and warm and the pleasant smell of the earth comes through the windows in the evening. I am never so far away from civilization that I can’t get a seed catalogue, and for thirty years I have been trying to solve the mystery of how to produce the kind of tomatoes that grow on the covers of the seed catalogues. I do pretty well, but I have never quite made the grade. I wonder if anyone ever has.

My catalogue comes to me from the air, for my friend, the pilot of the company’s plane, knows how much I count on it and he always brings it in. If landing conditions don’t favor him he comes in low over the lake and drops it where it is sure to fall in a clear place. I get my seeds the same way.

When it comes to tomatoes, which, raw or cooked, go well with almost everything, I have my own ideas. One is to plant them deep so that they will carry through dry spells without any trouble. I set mine half the depth of the stalk when they reach the transplanting stage. To protect them from cutworms I then make collars of strips of tar paper about three inches deep, leaving about an inch of collar above the ground. Some say not to stake your tomatoes, but I hate to see them lying on the ground, so I hitch mine to little birch branches and once they get started they take good care of themselves without much tying up. Although it will be a while yet before I get my garden under way I enjoy just thinking of pale green lettuce and pea vines bright against the rich black soil of my patch down by the lake. It was part of a little bog until I drained it; now it grows wonderful vegetables.

Up on higher ground where the soil is mixed with sand and well drained, I plant my potatoes early in June, for I depend on the late crop to put away for the winter. We grow very fine potatoes here in the woods and they have a flavor all their own, especially when baked in the ashes of a campfire. There is quite a trick to cut seed potatoes, for you get a better yield if you cut them so that you get the eyes on the flower end and in the middle instead of the stem end where the potato was attached to the plant. When the time comes to harvest the crop we have to watch for sudden cold rains which make potatoes soggy. Another thing is that if potatoes lie in the sunlight for any length of time after digging they turn green and are not much good. For keeping through the winter, potatoes should be stored in a dark dry place where the air circulates freely, but they must always be protected against freezing.

Rhubarb is one of the plants that I couldn’t do without, for nothing that comes from the garden in spring is so refreshing as stewed rhubarb, hot or cold, and if you have a little cream to pour over it and some hot biscuits to go along, you have a dish fit for any man. If you have no cream, evaporated milk goes very well. The right way to cook rhubarb is to simmer it slowly for about half an hour in a covered pot with just enough water to cover the bottom. Young stalks do not have to be peeled and cook up to a fine pink color. You need enough sugar to bring out the flavor.

I also grow fine carrots, beets; cabbage, and green beans, and I never fail to have herbs to flavor my cooking.

One of the troubles with gardens in the woods is to keep the deer out of them. There is hardly a fence you can put up that the critters won’t jump, but Wolf sleeps outdoors all summer and deer don’t get very close before he scares them off.

I don’t limit myself to vegetables for I’m more than passing fond of flowers and the color they give a place in summer. Along the south side of the cabin close to the wall I grow hollyhocks, deep red and rich yellow, and some white ones. Out in front I have several rows of sweet peas where I can see them from the porch and in the evening when the west wind stirs gently their scent comes to my window. Close by I always have a bed of nasturtiums, which do well here and are rich in color. I tried those beautiful bright blue morning glories for two or three years but didn’t have very good luck. Then a fellow told me that the seeds are flint-hard and should be nicked with a file and then soaked. That solved the mystery of why so many of my seeds failed to come up, so now I put them in a dish of water until they germinate and then plant them at once with the sprout straight up. If I want early blossoms I start the seeds in trays indoors with collars of tar paper around each one so that it can be transplanted without disturbing it very much. And for the birds I plant sunflowers all about the place, for the seeds make wonderful winter bird food, especially for chickadees. I always store away a plentiful supply. Once I discovered the endless pleasure of raising flowers I look forward to it every year. I don’t know anything akin to the excitement of going through a seed catalogue and discovering new strains to try my hand at.

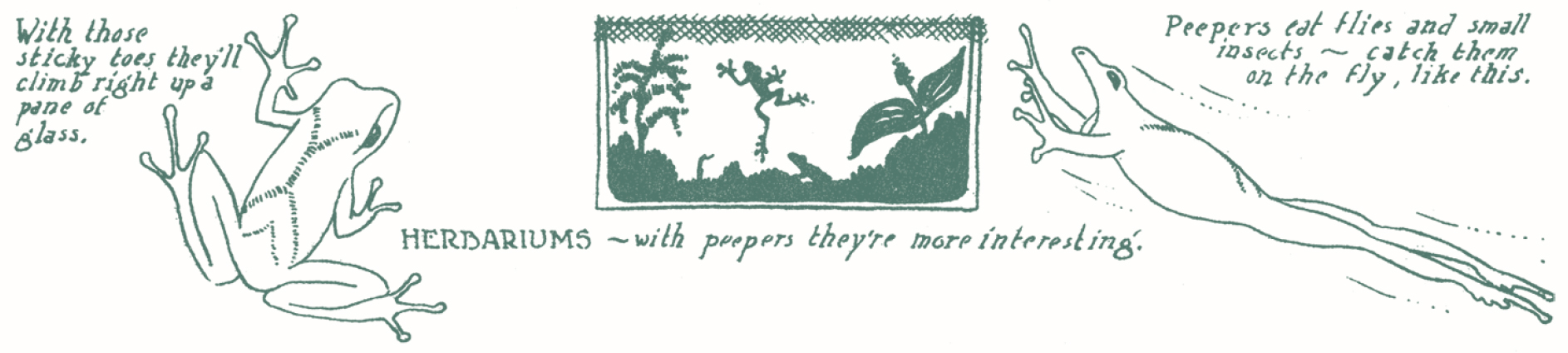

Almost every evening now that the days are warming I listen to the frogs in the swamp. Most people know the song of the peepers, but not one out of ten has ever seen one. It is hard to believe that a frog not more than an inch long can have such a big voice. They are fawn or brownish color, and have a cross on their backs. When they sing their throats swell out almost as big as they are themselves. They are tree frogs or hylas, and they have little sticky discs on their toes for climbing through the shrubs and grass when they are hunting for insects. Like all frogs, they go to pools and ponds in the spring to lay their eggs. They are hard to find, but at night you can locate them with a little patience. Flashlights don’t seem to bother them much, and, if you stand still for a while where they are singing, it won’t be long before you spot one of those round throats like a little toy balloon. They make nice pets if you keep them in a glass fish bowl or small tank with some moss and woods plants. The top has to be covered with a screen, or you won’t have them very long. They eat flies and most kinds of small insects, and they will sing for you, too. Pleasant neighbors.