Understand Your Brain, Understand Your Body

Most people who know me would call me the worst possible apostle for effective health management. Suffice it to say that I am not a member of the “my body is a temple” community. I am, however, a strong proponent of using the best tool for any given task—and to state it reductively, your body is the first tool that all other tools rely upon.

This gets into surprisingly difficult issues. I can think of many things that may be good for productivity while being “bad for you:” an afternoon energy shot, a cinnamon bun that lifts your mood, a cigarette, a metric truckload of caffeine. It’s not an either-or situation; some of these might work well for you and also not be the best idea.

As you read this chapter—meant to be an Owner’s Manual for Your Body as a productivity tool—you should make explicit choices, and figure out your own balance. A fair amount of advice here is to take better care of yourself. But some isn’t, and this book isn’t titled Take Control of Leaving An Attractive Corpse.

Experiment on Yourself

Your body belongs to you, and you should treat yourself like a scientific experiment. Change the inputs, and you’ll change the output; some inputs that seem extremely minor can affect you in profound ways.

There are several inputs that are obvious to everyone: sleep, diet, and exercise are the ones we talk about most. There are many others we don’t notice, possibly because they’re mostly beyond our control: air quality, how much sun we get, ambient temperature, or whether the times we eat are actually in accordance with how our blood sugar levels are varying. When you feel hungry enough to notice, you’ve actually been hungry for a while, and during that time you’ve made different decisions.

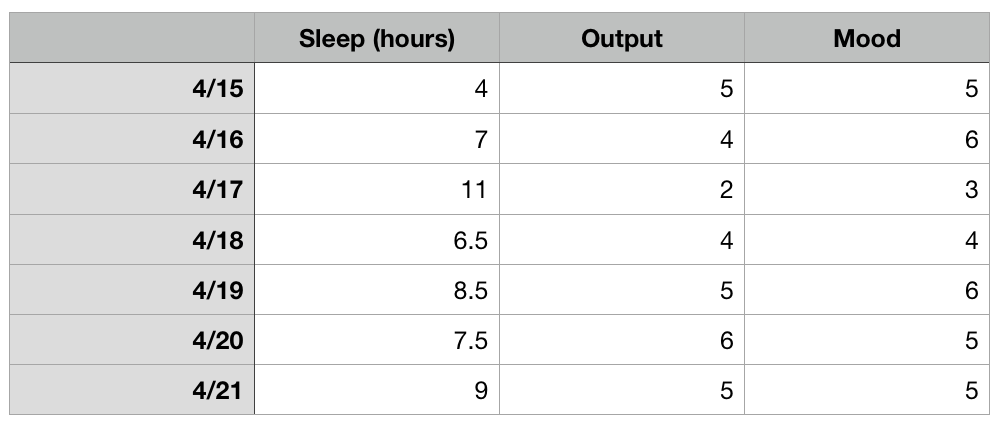

So what you do is vary one thing at a time, and track whether it makes a difference for you. Things to track: your mood, and your work quality and output, as in Figure 20. These things are not the same, and neither one is more important than the other until you say it is.

Some changes won’t make an obvious difference, and some may seem life-changing. Most often, you won’t be able to tell. Give them all a week or two. This is partially because you simply can’t trust your immediate observations, in much the same way that any new diet that makes you shed water will seem to work quick weight-loss miracles. The other reason is that after two weeks, if the effect is positive, you only need a week or two more before it becomes a habit. You’ve already done the hardest work of forming a new habit, in the spirit of being your own lab rat.

Try These Changes

My choices won’t work for you, so I’m not going to tell you what to do. Instead, these are categories of changes you should consider. What you actually decide should be entirely determined by what “improves” you, where you define the parameters for what’s considered an improvement. (I can’t stress enough: your parameters, not what everyone around you thinks you should do.)

Exercise

Hands down, move your body as often as you can. It’s good for you on nearly every measure any scientist has ever invented. You may or may not get productivity benefits from it. You’ll often hear people saying, “I get so much energy from my exercise!” Great for them; for me, exercising makes me tired, and tired makes me stupid. That doesn’t stop me from experimenting to find new approaches that don’t.

Figure out something to do, and do it regardless of whether it improves your work. It’s more important than simply getting more done. That said, it’s a perfectly sound decision to stick to only the methods that improve or are neutral to your productivity, so long as you don’t ditch them all.

Caffeine

There’s a weird backlash against caffeine that is entirely out of proportion with its actual health impacts. I suspect this comes from the “health is everything” crowd, who don’t much care which “chemical” you’re putting into your body—they’re all bad.

Caffeine is perfectly safe for people in normal health, in quantities including large amounts of strong coffee. It’s downing caffeine pills and those two-ounce energy shots that can give you a toxic dose; use sparingly.

Diet

This is your call. In my opinion, the quality of life that comes from a preferred diet possibly outweighs the health impacts of a proper diet. From a productivity standpoint, yes, what you eat for lunch has a far bigger impact on your afternoon than you realize. But diet modifications for productivity have to be very closely measured to be accurate. This is something I think is more important to calibrate to personal satisfaction, rather than some utopian health maximum.

As with exercise, this is something you put into place for a while before you see any benefit. But if you cut down on heavily caloric lunches, you should get an immediate result; food comas are a real thing, and there’s a reason why it takes all Thanksgiving weekend to wake up after Thursday overindulgence. Try a lunchtime salad, and see if your afternoons improve. Alternatively, if you eat an uberhealthy diet and feel awful and exhausted by noon, maybe try a bit more junk.

Sleep

Okay, I’ll expand on that. Believe it or not, a few of you are getting too much sleep, and it’s adversely affecting your work. Some people, but not many, physically need ten hours a night. But if you sleep a lot and you frequently wake up tired or groggy, that’s usually indicative of a physical or mental health issue. If you wake up refreshed from a long sleep, “a lot” could be how much you need.

Some of you are perfect. You get what you need. Maybe that was a deliberate choice based on paying attention to your body clock. Maybe you just got lucky; folks who need less sleep tend not to notice any difficulties. But people who do need more than they get also don’t notice, because deprivation has become their baseline. Nearly everyone thinks they can “get by” on less sleep. Psychological and physiological testing says they’re wrong.

If you’ve never measured your sleep consistently, you’re almost certainly wrong about how much you’re getting. It’s also possible to be unconscious but not getting any sleep benefits for part of the night. (If you want to create these conditions for yourself, just hit the snooze button; the interruptions ensure that you’re getting zero benefit from those extra minutes.) A smartwatch or other monitoring gizmo can help; there are also apps that measure your sleep habits when you put your phone on the corner of the mattress. Or make a daily note of how long you’re in bed, and your sleep hygiene (that is, how long it takes you to fall asleep, and how long you stay in bed after you wake).

Once you have these numbers, analyze them. If you regularly get little sleep weekdays and “catch up” on weekends, you’re sleep-deprived, full stop. Experiment with not doing that, and see what happens. Likewise, if you usually average eight hours, but this past month you had six, give some thought to whether that month was “good” or “bad,” and if that could have been affected by a cognitive deficit you didn’t notice.

I understand that many people simply cannot go to bed earlier or wake up later than they do, due to work schedules, children, social lives, the lure of the Netflix queue, the need to milk Bessie before she wakes up the goats. One possible solution: nap time, milk and cookies optional.

When you sleep is as important as how much you sleep, so track that too; it’s better when the sun is down (or in rooms with excellent light isolation), and it’s better with reasonably consistent times day to day.

Everything Else

There is no limit to how many ways you can experiment with your habits, and possibly develop better ones. (Again: “better” as you define that.) I could extend this chapter with discussion of what you do in the morning versus the evening, or what music you listen to and when, or how you feel after social activities.

I deliberately avoided the can of worms that is alcohol and (other) recreational drugs, because there’s nothing I can say that wouldn’t sound preachy to half of you, and overly permissive to the other half. I’ll just say this: if you do stuff to your head, pay attention to what happens when you do, and for a while afterward.

Good luck, get creative, then meet me at Starbucks for a nap or an espresso. I’ll probably be on my fourth cup of the day.