I started the new term in January 1986 nauseated at the prospect of having to see Lottie every day just a couple of weeks after she’d split up with me. It was my first experience of having to continue sharing a space, albeit a large space, with someone who had broken my heart, and every time I caught sight of her in Yard I felt poleaxed. How could she just be carrying on with her life? It was as if breaking up with me wasn’t the worst thing that had ever happened to her.

If we found ourselves in the same room, Lottie would smile and do her best to be friendly, but I acted as though she’d executed my entire family in front of me, then danced around their corpses listening to Shakatak (for younger readers, Shakatak had a number of hits in the 1980s with airy jazz-funk numbers that sounded as if they’d been rejected from a commercial for feminine hygiene products for being too insubstantial – in other words, the kind of music that would not be an appropriate accompaniment for dancing around the corpses of my dead family).

Dad announced we could no longer afford the splendour of Earl’s Court and Mum found a small terraced house in Clapham, South London. Initially sceptical, Dad perked up when he heard the area was becoming gentrified, but when he went to look round and discovered the gentrification hadn’t yet spread to the area we planned to live in, he perked down again. To him, the house in Clapham was a step backwards, but I thought it was a bijou property with tons of character (my room used to belong to an 11-year-old disco-dancing champion and was covered in Barbie stickers), with excellent transport links to Joe Cornish (two Tube stops away in Stockwell) and convenient access to an up-and-coming metropolitan shopping hub (we were just a few hundred yards from a food, booze and hardware shop that also rented out videos).

Our new house was also a short walk from Clapham Common, where Lottie lived, and on several occasions on my way home from a night out with friends I’d spend a while sitting on a park bench opposite her place, listening to a compilation of sad songs, staring up at her bedroom window and thinking myself romantic rather than creepy. A couple of times I was joined on my Bench of Sorrow by men who’d identified me as a possible cruising companion, and they paid for their mistake by having to listen to my tale of lost love before making their excuses and rejoining the night. At least I got to talk to someone.

The thought of talking to my parents about anything complicated or emotional was too embarrassing, and I suspected their advice would be some form of ‘Get over it’, which I didn’t want to hear. I was more in the market for ‘Why don’t you wallow in it for a very long time?’

Patrick was usually the person I confided in when it came to emotional matters, but he was stuck in his own romantic maelstrom and hadn’t been around so much. I tried pouring at least part of my heart out to Joe and Louis, but their response was to offer some superficial reassurance, then start laughing. They weren’t being callous; it was just unfamiliar territory for our relationship. I’m sure nowadays all teenage boys are sensitive, enlightened and always there for each other’s emotional needs, but for the average 16-year-old male back in 1986, listening to detailed accounts of heartbroken misery was not considered fun or interesting.

It was around this time I started to become more interested in alcohol.

With the possible exception of Louis, who was still even fresher faced than we were, most of our gang were able to get served at pubs and off-licences despite being legally underage. Booze, which had been gradually entering the picture for a couple of years, was now fuelling more and more of our get-togethers.

I should probably say right now that this isn’t building up to me describing how I went completely off the rails and made the decision never to touch another drop. For the time being at least, I still enjoy alcohol, but I don’t drink it for the same reasons or to the same degree that I once did, unless my mum’s coming over or I have to drive the children to school. Back in the sixth form, drinking on weekends made me feel as though I was taking a holiday from the awkward and anxious parts of myself I didn’t like – but that’s why most people start drinking, isn’t it? I don’t recall any of us standing round the Track & Field arcade game at Grafton’s pub in Victoria Street and remarking on the delicate blend of flavours in their pint of Foster’s. I knew it was naughty to be drinking in a pub underage, but that just made me feel like an outlaw and added to the fun. I didn’t think about my health because, other than occasionally having to make myself sick if I got the spins and feeling a bit soft and blurry the morning after a drunken night, I didn’t think it was doing me much harm.

For the next decade or so I had more or less the same attitude to alcohol that my parents and many of their friends did: that you only had a problem if you regularly started your day with eight cans of Special Brew on a park bench, talking to yourself and trying to punch people, but if the sun was past the yard arm, it was happy hour! And then there was smoking …

Mum and Dad had both smoked cigarettes but had stopped when I was still little, and by the time I was 15 I was a strident, self-righteous anti-smoker, loudly contemptuous of school friends who had begun to dabble, thinking them dreadful posers.

Then, on our family trip to China in 1985, I’d been wandering through a street market one day in Guangzhou looking for some edgy souvenirs to take back to school, when next to a display of lock knives a table filled with packets of cigarettes caught my eye. They were beautifully and intricately designed – all brightly coloured dragons and flowers – and in those days there wasn’t a single warning or decaying body part in sight. I bought three packets for the equivalent of 15p and back at school I gave one to Patrick and one to Joe as a kind of joke.

Then late one night at school, in my single study at the very top of the house, I took a break from Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, crawled onto the low-walled, sloping section of roof outside my window and lit up my first cigarette while listening to ‘The Funeral Party’ by The Cure on my Walkman. It was completely revolting – the cigarette, not The Cure. I was relieved. ‘I guess I’m not a smoker,’ I thought. But the next time we had a weekend boozing session I took the pack with me as a prop, and after a couple of drinks I tried another. This time it wasn’t so bad. In fact, when taken with alcohol the overall effect was rather pleasant and immediately made me feel complex and adult, which of course was the object of the exercise.

I still have a few minutes of home video shot around this time of a fairly typical Saturday-night excursion beginning with Joe and Louis messing about on a Northern Line train before getting off at Leicester Square and meeting Ben at Burger King for a Coke and a smoke while leafing through Time Out and deciding what film to see. That night it was Jean-Jacques Beineix’s (Bay-nex) epically saucy drama of doomed romance, Betty Blue.

When the long, energetic sex scene that opens the film was finally over and our teenage trousers were beginning to slacken, most of the people sat in the smoking section (the right-hand side of the auditorium) lit up a cigarette. Everyone laughed because in those days it was common knowledge that after you’d had a bonk you had a ciggie. Though we were all virgins, we got the joke and sparked up, too, feeling very sophisticated for doing so, and after another scene in which Betty and friends drank Tequila Slammers, we stayed up late into the night at Ben’s place in Kentish Town (his mum was away) and did the same.

RAMBLE

Part of me wishes I could go back and rescue the 16-year-old Buckles from a time in which so many self-destructive urges were normalised and glamorised, and set him on an altogether more salubrious path. But 16-year-old Buckles, once he’d got over the excitement of finding out time travel was real, would probably tell 50-year-old Buckles to stop being a hypocrite and fuck off back to his own far-from-perfect time and concentrate on doing a decent job with his own children, who as I type are probably busy finding their own ways to do the ‘wrong’ thing, as teenagers always will.

Can I blame my parents for not giving me better guidance when it came to love and other intoxicants? I’d love to, but they were busy with their own shit, and anyway, as one of my school reports once pointed out, I had the capacity to be ‘sly and underhand’ and was adept at keeping Mum and Dad in the dark when it came to most of my bad behaviour. But maybe I wouldn’t, have been so sneaky if I hadn’t been sent to boarding school. Or if I’d never been born. One way or another, I’m pretty sure it was my parents’ fault.

The Ghost of You Clings

As far as I was aware, Roxy Music were just old guys in dinner jackets who hung around with beautiful, much younger women at boring-looking parties on the French Riviera (where the DJ would probably be playing Roxy Music). ‘You should listen to the early stuff,’ said Patrick, so when the Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music compilation Street Life was released in 1986, I gave it a go.

Although most of the tracks catered mainly to the Yacht Roxy crowd, ‘Love Is the Drug’, ‘Pyjamarama’ and ‘Virginia Plain’ immediately jumped out as the kind of strange, arty pop that Bowie had encouraged me to appreciate. I also found myself enjoying some of Ferry’s wonky covers, despite (or perhaps thanks to) not being familiar with the originals. I played ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’ over and over, thought ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’ was lovely and ‘These Foolish Things’ was a hoot.

I made sure to bring my cassette of Street Life on the coach that had been hired to take a load of us sixth-formers to a party at our friend Guy Gadney’s house in Cheltenham during summer half-term. I was still pining for Lottie, but she wasn’t going to be at the party and there was an atmosphere of new sexy possibility, so I boarded the coach determined that by the end of the night I would be involved with kissing.

I asked the coach driver if he’d play my Roxy Music cassette and soon we were joining the A40 to the sound of Bryan Ferry warbling, ‘So me and you, just we two, got to search for something new’. By the time ‘These Foolish Things’ came on I had drunk one of six large cans of Foster’s I’d brought with me and was miming to the lyrics along with Patrick and a couple of other pals. Amazingly, a few of the girls laughed and joined in. ‘Wow,’ I thought. ‘I think we might be the coolest, funniest people alive right now! If this coach journey is anything to go by, this is going to be the greatest party of all time, and kissing is definitely on the menu.’

Another can of Foster’s later, I was desperate to urinate, but there was no toilet on the coach and we were on the motorway, so a quick stop wasn’t an option. I’m not someone who can just ignore a full bladder and carry on with my life. All I can think about is when and how the discomfort will end. I asked the driver how much further we had to go and he said about half an hour. I was not going to last half an hour.

Rather than rejoin Patrick and the others at the back of the coach, I found an empty row, took the window seat, leaned forward and began making idle chit-chat with Boring Des McKenzie sat in front. Talking to Des was hard work, but I needed an excuse to lean forward so my long coat would disguise the fact that I was unzipping my flies and positioning myself to access the opening of one of my empty Foster’s cans. As any willy owner who has ever done this knows, it’s a very delicate procedure, fraught with aiming challenges and sharp-metal peril.

When I was confident that receptacle and nozzle were sufficiently well aligned, I began cautiously to proceed with the transfer. Waves of sweet relief washed over me as I tried to look interested in whatever Boring Des McKenzie was burbling on about, but when the can started to grow warm and heavy, my satisfaction turned to anxiety. I knew it must be nearly full, but the transfer was far from complete. I was able to strangle the flow before total catastro-pee, but as we took the exit for Cheltenham, I realised with great sadness that a significant amount of piss had missed the can entirely. There was now a large damp patch on the front of my jeans that would be hard to explain as anything other than a pee-pee accident, and that kind of explaining is low on the list of things you want to do when you’re a teenager hoping to kiss someone at a party.

As the coach pulled up outside Guy’s house, I draped my coat over myself to conceal my shame, then waited for everyone else to get off before I disembarked gingerly, carrying with me the warm beer can filled with my own amber nectar. I poured away the contents beneath the coach, then, determined to find a bathroom in which to deal with the situation ASAP, I made my way into the party.

Inside the bathroom I locked the door, lowered my jeans, sat down on the lavatory, folded several sheets of pink toilet paper and began rubbing away at the wet patch. This succeeded only in creating a collection of tiny pink toilet-paper sausages that I brushed despondently from the damp denim. Feeling the lighter in my jeans pocket, a great idea hit me: why not dry the pee-pee patch using man’s red fire? I would need to apply the heat to the inside of the jean so as to avoid unsightly carbon deposits on the front, and I would need to keep the flame moving so as not to burn a hole, but it should work.

I had begun to take off my jeans when there was a loud knock at the bathroom door. ‘Won’t be long!’ I called out. I had to move fast – there was no time to remove the jeans completely. Still sat on the toilet, I pushed them further down my thighs and spread my knees so as to pull the damp area taut, then clicked a guttering flame into life and carefully introduced it to the inside of the moist denim, but as I did so there was another loud knock and a female voice said, ‘Are you going to be much longer?’ Before I’d had a chance to reply, the hair on my inner thighs caught fire.

Patting out the flames, I hastily hoisted up my pee-pee jeans and flushed the toilet. The bathroom smelt of burnt hair as I threw open the door, making sure not to make eye contact with the girl behind it, and marched as quickly as possible to the darkest corner of the room, only to find it occupied by Boring Des McKenzie. Feeling we had bonded on the coach, Des unveiled his party piece: a recitation of Chapter 1 from The Restaurant at the End of the Universe by Douglas Adams, which he claimed to have memorised, insisting on starting again every time he made a mistake (which was often). There was no kissing for me that night.

Crosseyed and Painful

As a day boy, Joe was allocated a boarder’s study that he could use as a base during school hours. The lucky boarder who played host to Joe (and everyone else who Joe invited to hang out during so-called ‘private study’ periods) was Paul Dales. A gifted musician and tech enthusiast, Paul always had some classic album playing through his expensive NAD amplifier and asked that visitors refrain from tampering with the configuration of his EQ sliders. We’d seen Tom Cruise’s character Joel in the film Risky Business being asked the same thing by his dad, so being the impressionable arseholes we were, we did exactly what The Cruiser had done and jammed Paul’s equaliser sliders up to the max whenever we got the opportunity. ‘Sometimes you just gotta say what the fuck,’ we said, quoting Risky Business. Paul sighed wearily.

Paul listened to music that I wasn’t yet equipped to appreciate: Weather Report, Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis, as well as stuff that just sounded daft to me: Frank Zappa and early Genesis – full of madly complicated instrumentals played very fast at strange time signatures, occasionally pausing for some unfunny word bollocks. ‘Not nearly as good as the Thompson Twins,’ I thought. Then one day I went to hang out in Paul’s study and he was playing an album that sounded even better than the Thompson Twins.

The songs were sparse and choppy, the singer odd and interesting. He sang in a strained high-pitched voice about his loved ones driving to the building where he worked and suggesting they should park before coming up to see him ‘working, working’. The singer said he would put down what he was doing because his friends were important. The strange formality of the lyrics made me laugh.

I realised this was the same guy who had done a song I remembered from boarding school, a song that had been in the charts when Patrick got angry with me for not caring that John Lennon had been shot: ‘Same as it ever was, same as it ever was,’ it said. I looked at the cover of the cassette Paul was playing and saw that it was called THE NAME OF THIS BAND IS TALKING HEADS. All caps. Mmmm. Pleasing.

Paul let me make a copy of the cassette and I liked it more every time I played it, even though the music was less straightforwardly poppy than most of what I tended to listen to, and despite the fact that it was a live album. I didn’t get the point of live albums. The few that I’d heard always seemed much worse than the original studio recordings, but THE NAME OF THIS BAND … was different. It was tight, sparse and solid, and I was beginning to realise that was how I liked my music (and, yes, my turds, too).

Once I was sure Talking Heads and I were getting on sufficiently well, I started buying their albums, beginning with 77 (that had the ‘working, working’ song on it: ‘Don’t Worry About the Government’), then More Songs About Buildings and Food and Fear of Music. Scanning the inlays of those last two, I noticed they had been produced by Brian Eno and I thought I could hear what he added to songs like ‘With Our Love’ and ‘Air’: a weird mood somewhere between exhilaration and menace that I also heard on some of the stuff Eno did with Bowie – on ‘Red Sails’ or ‘Sons of the Silent Age’, for example (my editor’s going to tell me to lose this stuff because it’s too boringly muso. I won’t argue if he does, so if it’s still in it’s his fault).

Paul had put together a few short-lived bands at school. One of them, The Generators, had played in the big main hall (known as ‘Up School’) a couple of years previously, with Joe singing ‘What Presence?!’ by Orange Juice. Paul’s new band had just changed its name from Quadrant to Shady People and it included Patrick on guitar (Joe had quit by then due to creative differences).

I had watched Shady People rehearsing once or twice in the music centre and I’d entertained Paul and Patrick by grabbing a mic and singing Freddie Mercury’s falsetto parts from ‘Under Pressure’. I thought it would be great to be in a band, but learning to play an instrument seemed too much like hard work, so I was pleased when Paul suggested I provide guest vocals for an upcoming gig. I would be singing lead on Shady People’s cover of the Talking Heads track ‘Crosseyed and Painless’. A couple of weeks before the gig, Paul gave me a VHS of their concert film Stop Making Sense and I got to work learning the lyrics.

I bought Remain in Light, the album that has ‘Crosseyed and Painless’ on it, but other than ‘Once in a Lifetime’ (the ‘same as it ever was’ song), I didn’t like it as much as the more conventionally structured songs on their earlier albums. Remain in Light was more like dance music and I wasn’t so keen on dance music. That was the preserve of sexy, unselfconscious people, not little hairy hobbit men. I would have preferred to sing ‘The Big Country’ or ‘Pulled Up’, but ‘Crosseyed and Painless’, being more of a rap, was probably better suited to my limited vocal talents.

By the day of the show I had worked myself up into a dangerous pitch of excited anticipation and mortal terror. When lessons were over I went up to my study and changed into my show clothes: a pair of Chelsea boots I’d borrowed from Patrick, my skinniest black jeans, a blue collarless shirt (with top button done up) and, to cap it all off, a big-shouldered white jacket that I had bought in Camden over the summer. It was intended as a nod to David Byrne’s big square suit from Stop Making Sense, but what it said loudest was, ‘I just stole this from a waiter.’

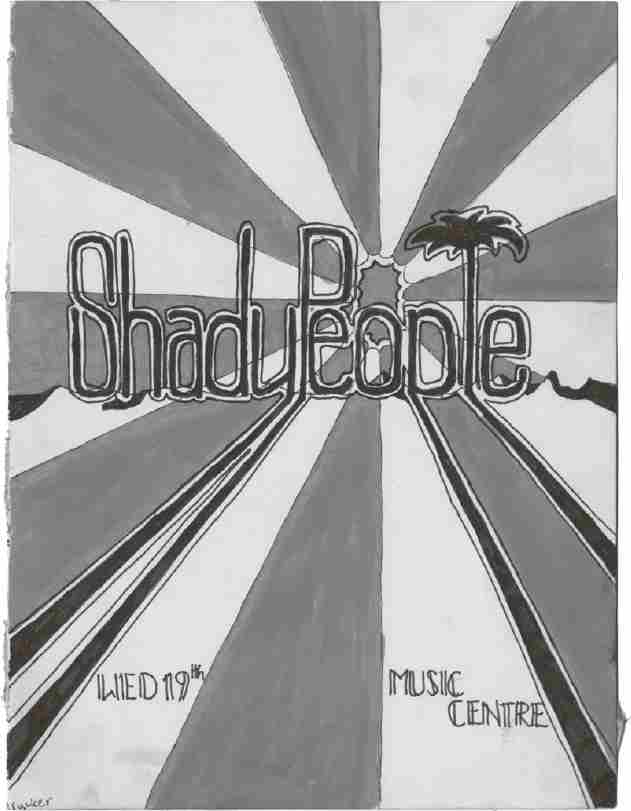

My poster for the ill-fated 1986 Shady People gig at which I sang guest vocals. Sort of.

Patrick came into my study with a couple of the coolest girls from our year, Lottie’s friend Julia, who was going out with Patrick, and Saskia, who only went out with boys from the year above. The guy in the study next door to mine saw them arriving and looked impressed. I flashed him a look that said, ‘Yup, you’d better believe it,’ and closed my door. Patrick had drafted in the girls to sing backing vocals at the gig, but they were as nervous as I was because they’d heard rumours that high-ranking members of the Lads were planning to come and disrupt the show. Patrick told us not to worry as he was friendly with some of the Lads and, anyway, he had a bottle of wine. We passed it round and within 10 minutes it was empty, whereupon we tottered off to the music centre.

Gigs like these were unusual at the school and the room was packed with curious onlookers from the years below sitting on the floor. I quickly scanned the room and there, leaning against the back wall in a line of statement haircuts and sarcastic grins, were about five core members of the Lads. Shady People started playing their set of unfashionably funky covers and clunky originals and, feeling queasy, I crouched to one side and waited for my guest spot, hands thrust deep into my big white jacket pockets, hoping that no one would snap their fingers and ask me for the bill.

Then I was up, and as I made my way to the microphone a few of the Lads began to chant, ‘Talking Heads! Talking Heads!’ while laughing to make it clear that they did not, in fact, appreciate Talking Heads. I glanced at Patrick. He looked stressed. Paul counted us in and the band started playing a ragged ‘Crosseyed and Painless’ as the Lads laughed and pointed.

In a film, this would be the moment where my character looked around the room as the din of the music and the hoots of derision faded beneath a loud, reverberating heartbeat. Then my character would find something in himself and rise to the occasion, delivering a performance that would leave the Lads nodding with reluctant respect.

But this being reality, it’s the moment I fucked it.

I got through the ‘Facts are simple and facts are straight …’ rap, doing my best to ignore the Lads nodding, stroking their chins and cackling, then I caught Patrick’s eye and with an exchange of cringing glances, we agreed to bail.

Stumbling my way through the audience to the door of the music centre, I looked back briefly to see Paul prodding away funkily at his synth and looking incredulous as he watched us leave. My response was to shrug, then grin at the Lads in spineless solidarity. Out in Yard we laughed. I went up to my study to change out of my waiter’s jacket and we went to the pub. Rock and Roll.

In a long list of shameful behaviour from my Westminster days, that gig and the way we treated Paul is not at the very top, but it’s certainly up there.

Despite the Shady People débâcle, my enthusiasm for anything related to Talking Heads continued to grow, though it took another few years for me to properly appreciate Remain in Light and to stop squirming with regret whenever I heard ‘Crosseyed and Painless’.

America Is Waiting

As an A-level Spanish student I got to attend a three-week course in the Spanish city of Salamanca at the end of the summer holidays in 1986. I didn’t learn much Spanish, but I loved exploring the bars and clubs of Salamanca with a group of friends that included Guy (of the Cheltenham pee-pee-patch party) and Theodora, a student from New York who invited me out to stay at her parents’ place in Bayonne, New Jersey, during the Christmas holidays.

When I arrived in New York, Theodora kindly came to pick me up from JFK airport, but it wasn’t long before we realised that the magical party chemistry we had shared in Spain had remained in Spain. After an awkward couple of days, Theodora mysteriously discovered she had prior family commitments and said regretfully that I had to find other lodgings. So I called Chad.

Chad was an American exchange student who had arrived at Westminster earlier in the year and had quickly become part of our gang. He was like an older brother, more worldly and physically mature than we were. He listened to grown-up music like Led Zeppelin and Little Feat, had a cryptic tattoo on his leg and planned to go into business making cannabis-infused beer. But, best of all, he was funny and American, like Bill Murray.

Chad said I could stay with him at his parents’ place, a brownstone on East 93rd. However, as with Theodora, my friendship with Chad had been forged on neutral territory, and now on his home turf, surrounded by his family and friends, the relationship at first seemed less easy-going.

We went to a drinks party in an uptown apartment block that had marble floors and a doorman. The living room looked like a posh hotel suite and was filled with smart preppy types chatting and drinking champagne.

Graceland by Paul Simon was playing. Chad introduced me to a couple of the less preppy and more approachable people, but I was nervy and looked odd in skinny black jeans, scuffed Chelsea boots and my shabby over-sized black suit jacket. It wasn’t long before I was perched on the arm of a Regency sofa smoking cigarettes on my own, missing Joe and thinking what a wanker Paul Simon was.

The next night we stayed in and had takeaway with Chad’s dad who suggested we rent a film. Chad and his dad wanted to watch something classic, Dirty Harry or Bullitt, but I suggested Dark Star, confidently predicting that they were going to love it. By the time Pinback was battling the inflatable beach-ball alien, Chad’s dad was asleep, Chad was smiling politely and I was feeling out of sync with the world.

Chad was off doing other things during the daytime, so I explored New York on my own. Each morning I took the Subway to Brooklyn and spent a few hours tagging and buying rare hip-hop records, then in the afternoon I’d skateboard to a few galleries before getting some food in Chinatown and catching something challenging at the theatre. Oh, hang on … sorry, I was thinking of someone more interesting. What I actually did on every one of the five days I was in New York in 1986 was walk down to Tower Records in Greenwich Village – New York was in the grip of a long crime wave at the time and I decided walking was safer than taking the Subway.

I liked walking around the city, my big overcoat pulled tight around me, stopping now and then to stick another cassette in my Walkman. I listened to Echo and the Bunnymen’s greatest hits album, Strange Days by The Doors, I’m the Man by Joe Jackson, True Stories by Talking Heads and the soundtrack to a film I’d seen recently on TV: Midnight Cowboy. As I walked, I sucked in my cheeks and tried to affect the gaunt inscrutability I admired in David Byrne, but when I caught sight of my reflection in the windows of delis, dry-cleaners and department stores the little fellow peering back at me looked less like the Talking Heads lead singer and more like a plump Ratso Rizzo.

At Tower, I gazed at the giant handmade displays the art department had created for various new acts, then searched in vain for Talking Heads albums I didn’t already own. Looking under ‘B’ for Byrne, I found My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a collaboration with Brian Eno that I bought and listened to as I trudged back to East 93rd.

It contained what sounded to me like ominous ethnic robot music overlaid with recordings of people chanting, delivering monologues and ranting on radio phone-ins. It was very good, and the following day I bought The Catherine Wheel, an album of music composed by David Byrne for a theatre project by dancer and choreographer Twyla Tharp (a name that surely predisposed her to being either a dancer and choreographer or an ornery gold prospector with an idiosyncratic mule). The Catherine Wheel sounded like the midway point between Remain in Light and … Bush of Ghosts, i.e. polyrhythmical, experimentalocious and samplerific.

By this time I was thinking David Byrne could do no wrong, and my final New York purchase was Music for ‘The Knee Plays’, an album put together in 1984 as part of an avant-garde opera by experimental theatre maestro Robert Wilson. After the joy of discovering … Bush of Ghosts and The Catherine Wheel, The Knee Plays came on like indefensibly pretentious dog crap that threatened to make me think less of my beloved Mr Byrne. Every track featured mournful brass-band music with Byrne occasionally reading out lyrics that might have been written by a child on the least interesting part of the spectrum.

‘She turns on the tap and the water comes out, so she fills up a glass and drinks it. The glass is good for holding water. Other things that are good for holding water are bowls, bottles, and bags, but not jackets. Jackets are good for holding groceries …’ I made those lyrics up, but that’s the sort of thing you’re dealing with.

I played Music for ‘The Knee Plays’ a couple of times just to check I hadn’t judged it too harshly, then, deciding that I hadn’t judged it harshly enough, I put it away and forgot about it. Five years later, at art school, I stuck it on one afternoon out of curiosity. Suddenly, in an environment that lovingly nurtured indefensibly pretentious dog crap, Music for ‘The Knee Plays’ sounded magnificent; the brass-band music strange and hypnotic, and Byrne’s lyrics intriguing and funny. It’s still one of my favourite albums to listen to if I’m doing manual labour or working on a new installation that explores the tension between collective memory and farts.

Fubar

On my last night in New York Chad invited me to join him and his friends Ralph and Hank on a trip to see a new film everyone was raving about called Platoon. There was a big queue of people standing in the cold outside the cinema, but rather than join the line immediately, Ralph led the way round the corner and lit a joint.

Mum had told me that people who smoked marijuana ended up injecting heroin, and I knew from the ‘Heroin Screws You Up’ public information campaign that heroin instantly gave you spots, made you ill, then killed you – three of my top Worsties. But Chad, Ralph and Hank were cool, funny and friendly, and I didn’t want them to think I was uptight, so despite the risk of spots, illness and death, I had my first drag on a joint.

I started to feel dizzy almost immediately, but when Chad and the others headed back to the cinema I did my best not to let on and concentrated on putting one foot in front of the other as I followed them. Back in the queue for Platoon, with the edges of my vision darkening, I suddenly felt a sensation like water flushing from my head down through my body, and before I’d had a chance to warn anyone, my legs had buckled and I’d sunk to the Manhattan pavement (or ‘sidewalk’).

I was aware that Chad and the others were peering down at me with expressions of concern and amusement, but I was too spaced out to care. My only vaguely coherent thought was that one of New York’s many muggers might be making a note of my defenceless state and adding me to their ‘To Mug’ list. However, I also knew that if I was helped to my feet, I would black out completely, so I sat cross-legged in the queue as Chad, Ralph and Hank kept me entertained doing impressions of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Elmer Fudd fighting in Vietnam. ‘It’s Loony Platoony!’ said Hank, and everyone in the queue laughed, even Ratso having a whitey on the pavement.

By the time we were seated in the packed auditorium, I felt like Major Tom floating about my malfunctioning tin can and wondering if I’d ever make it back to earth. Then Platoon started.

Like Charlie Sheen’s character, I felt I’d been dropped in the middle of an overwhelming nightmare and was struggling not to panic. My fearful confusion peaked about 15 minutes into the film, during a chaotic night-time jungle firefight scene in which Star Wars-style laser bolts appeared to be zipping between the soldiers. ‘Why are there lasers in the jungle?’ I whispered to Chad.

‘Dude, they’re tracer bullets. How you doin’, man?’ smiled Chad.

‘I’m OK, I think.’ I was no longer in physical difficulty, but every intense and upsetting scene was emotionally amplified and I was helplessly grateful for Willem Dafoe’s kindness, scandalised by Tom Berenger’s ruthlessness and in love with Charlie Sheen.

When Platoon was over we said goodbye to Ralph and Hank and began walking back through the sobering cold to Chad’s place. My stomach was groaning so I bought a flapjack square from a convenience store and wolfed it as we walked. It was the best thing I’d ever tasted – like biting into eternal love. Chad laughed as I ran back to the store and bought another ten.

The next day I woke feeling foggy and sad. I liked the Buckles who had never smoked drugs, but now, with a single puff, he was gone forever. My consolation lay peeking out from beneath the pile of clothes on the floor by my bed: the Flapjack Squares of Eternal Love. I reached over for one, unwrapped it excitedly and took a bite. It was like sawdust from a hamster cage.

BOWIE ANNUAL

I didn’t investigate Bowie’s 1977 album “Heroes” for ages because I wasn’t fond of the title track. My favourite Bowie songs were mysterious caverns in which nameless feelings were illuminated by lines like ‘… it was midnight back at the kitchen door, / Like the grim face on the cathedral floor’, but the sentiments in “Heroes” just seemed a bit obvious, triumphalist even. Blah blah, Kings, blah blah, Queens, blah blah, aren’t dolphins brilliant? Yeah! Let’s spend the day beating people.

I liked the “Heroes” album cover, though. The black-and-white shot of Bowie staring blankly with stiffly posed hands was exactly the kind of robotic sexiness I was after from Zavid, so, hoping there was more of that inside, I eventually dived in.

I’d never been to Berlin, but after listening to “Heroes” a couple of times I felt as though I’d been stuck there for months, talking to weirdos in a dark, rainy alley outside a jazz club where they keep the bins and all the jazz people do their wee-wees. With the exception of the title track, “Heroes” was full of music I couldn’t imagine anyone else in the world listening to (especially ‘Joe the Lion’ and ‘Sons of the Silent Age’), and I got into it much faster than I had any of his albums previously.

Side two contained more instrumental ‘moodscapes’. Like Low, but bleaker. I especially liked ‘Neuköln’ (Noykern), which I thought of as the soundtrack to the rainy alley outside the jazz club, the desolate wails of Bowie’s saxophone at the end sounding like someone who’s just discovered their lover has been murdered. Or maybe they’ve just lost their wallet and missed the last bus home. Either way, somebody’s having a shit evening.

One weekend late in 1986, while I was still in my sanctimonious pre-marijuana days, I found myself the only not-stoned person in a group of stoned people who wouldn’t shut up about how stoned they were. Feeling fed up and left out, I put on ‘Neuköln’, turned out the lights, held a torch under my mouth and lip-synced to Bowie’s anguished saxophone screams until one of the stoned people started to get the fear. The rest of them told me to stop being a prick and turn the lights back on.

RAMBLE

I bet some of you are still annoyed by what I said about the song ‘“Heroes”’. Perhaps I went a bit overboard. I always liked it perfectly well, but it took me another 30 years to properly appreciate it. In 1986 the thing I liked best about Bowie’s Seventies music was that it made me feel like a member of an exclusive club, and the song ‘“Heroes”’ felt like an anomaly, because, as with ‘Let’s Dance’, the door policy was too slack. After he died, ‘“Heroes”’ became a rallying point for brokenhearted fans and the remnants of my snobbery fell away. Every time I showed the video for ‘“Heroes”’ at the end of the BUG David Bowie Specials I did in the years following his death, I got weepy.

The best bit about Bowie’s cameo in Absolute Beginners, Julien Temple’s stagey adaptation of Colin MacInnes’s novel about late-Fifties London groovers released in April 1986, is a tiny moment when his advertising-executive character Vendice Partners is showing the film’s protagonist Colin a model of a new housing development. ‘It’s lovely,’ says Colin hesitantly, and for a moment Bowie drops the rotten American accent he’s been doing and says in his own geezerish tones, ‘No, it’s not, son, it’s ’orrible.’ Then he goes back to being crap American again.

To me it seemed as though the real David, my David, the arty contrarian who just nine years before had released Low and “Heroes” a few months apart, was peeping through the Eighties and saying, ‘What am I doing here? It’s ’orrible!’

Now his musical output was a series of histrionic pop songs of variable quality tied to other projects: the brilliant ‘This Is Not America’ from the film The Falcon and the Snowman; the less brilliant but thoroughly amiable cover of ‘Dancing in the Street’ with Mick Jagger for Live Aid; one excellent and two so-so songs for the Absolute Beginners soundtrack; the blustering ‘When the Wind Blows’ for the depressing animated film of the same name and a good, uplifting theme song along with four other pieces of syrupy cat sick for Jim Henson’s film Labyrinth (though I’m aware there are people who believe ‘Magic Dance’ to be a work of stone-cold genius).

Indeed, many fans will tell you Labyrinth is where their journey with Bowie began, but when Joe, Louis and I went to see it at the Odeon Leicester Square one Saturday night a few weeks after it was released in November 1986 I thought it was where my journey with Bowie might end.

At 17 I was too old to find Labyrinth delightful and too young to embrace it ironically. I didn’t like the songs; I didn’t like the middle-aged Goblin King’s Kajagoogoo wig or the fact that his name was basically ‘Gareth’; I didn’t like Gareth’s unsavoury obsession with a young girl, and I didn’t like being able to see the outline of Gareth’s genitals through his leggings – at least, not as much as you might expect.