It was easy to see the Beastie Boys as just three chancers from privileged backgrounds who had cynically hijacked the sounds and styles of working-class black hip-hop culture to promote their own frat-boy agenda. That wasn’t true (not entirely), but whatever they were up to, by the spring of 1987 it was working very well.

The single ‘(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)’ and the album Licensed to Ill had brought the Beasties to the attention of a massive audience, which included people like me, who felt threatened by ‘real’ hip-hop but were happy to buy into Mike D, Ad-Rock and MCA’s whitewashed pantomime of obnoxiousness.

For me, Joe, Louis and our pals, this opportunity for mindless steam off-letting was perfectly timed. We were taking our A levels, after which the plan seemed to be to leave school and piss about for a while before getting back to making good on our parents’ investment in our education. Joe was planning to go to film school and Louis had applied to Oxford. I knew they’d both get in and their lives would work out the way they wanted, and I envied them. I didn’t have a clue what I was going to do. Apart from hanging out with Joe, the only thing I really enjoyed was drawing.

The one time I asked one of my tutors about art school as an option, it was explained to me that unless you were freakishly talented and got into the Slade or the Royal Academy, art school was a waste of time, somewhere thickos and slackers ended up if they couldn’t get into proper university.

‘Screw you and your conformist establishment sausage factory, Mr Tutor! Maybe I’ll never be a great artist, but at least I’ll be following my passion for doing passable drawings of robots and pop stars!’ I didn’t shout, having not jumped onto a table with a wild look in my eyes.

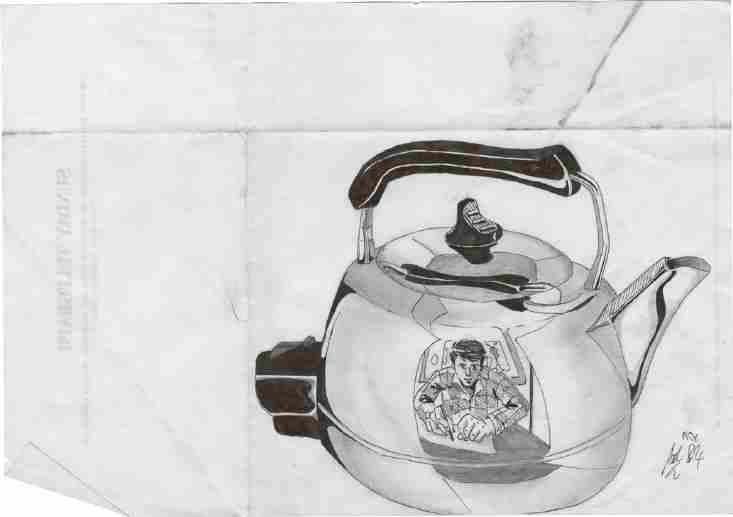

Breathtaking realism in this still life/self-portrait from the 15-year-old A. Buxton.

Instead, I glumly filled out the UCCA form, applied to do English at a selection of universities I was never going to get into, and tried to ignore the chasm of uncertainty that lay on the other side of the summer by fighting for my right to party.

Meanwhile the Beastie Boys had become tabloid fodder in the UK, with British journalists taking their shtick at face value and doing their best to spread moral panic whenever possible. Although I think moral panics should be treated with suspicion and would never advocate artistic censorship, I also have to acknowledge that the Beastie Boys’ influence on me as a teenage man was almost completely negative. Their record gave me licence not only to ill, but to act on occasion like a massive prick when hanging with my homeboys. Apart from promoting a lame kind of ironic misogyny and homophobia, the Beasties were seemingly never without a six-pack of Budweiser, and that played a part in encouraging me to think of excessive beer consumption as entirely harmless man fun.

Throughout 1987 we’d often head out to a small hill in St James’s Park and ‘shotgun’ cans of Budweiser, something we’d learned how to do from the film The Sure Thing, which starred another notorious corrupter of youth, John Cusack. ‘Shotgunning brewskis’ entailed holding the beer can upside down, punching a hole big enough for a finger to fit through at the side of the can near the base with a sharp object, covering the hole with your mouth, then raising the can upright and pulling the tab. Then you had to glug as fast as possible as the whole beer shot down your throat in a matter of seconds. This was followed by belching, can crushing, possibly some high-fiving and a sense that you were living life to its fullest.

There would have been shotgunning on the last night of the February half-term in 1987 after Louis, Joe, Zac, our American-exchange friend Chad and I went to see David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly at the Odeon Marble Arch.

RAMBLE

Unlike Alien, which frightened me in a fun way, the fear I got watching The Fly was altogether more disturbing, a nauseating dread of disease, disfigurement and physical decay, albeit leavened by Jeff Goldblum’s top-notch handwork. The part I found most upsetting was the scene in the bathroom when Goldblum’s scientist character Seth Brundle, having accidentally fused his DNA with that of a housefly after stepping into a teleporter together, was studying the progress of his physical transformation from Sexy Jeff to hideous Brundlefly with mounting alarm. There were groans of revulsion sprinkled with a few chuckles in the audience when he squeezed the tip of a finger and it squirted at the mirror like a popped zit, but as Jeff peeled away a rotten fingernail with a breathless wince, the mood became more sombre. And that was before the ear came off.

As I watched The Fly for the first time, the bathroom disintegration scene evoked the alarming indignities of going through puberty and the constant worry that my body was changing in ways that were not ‘normal’, let alone aesthetically pleasing.

Watching The Fly again more recently, the scene played out as an allegory for the physical process of ageing and the moments – increasingly frequent after my dad’s death – when I catch sight of myself in the bathroom mirror and it’s breathless wince time. Only the relatively slow pace of the deterioration prevents full-flailing panic, but essentially, I’m Brundlefly, except that instead of sharing the teleporter with a fly, I shared it, as we all do, with that stupid old bastard Father Time.

Sub-Ramble

Despite being Brundlefly, I’ve found the benefits of being older outweigh the disadvantages, and though my vanity is not deserting me at the same pace as my cowardly hair, it’s not the source of frequent discomfort it would have been in 1987. So that’s nice.

We emerged from the Odeon Marble Arch somewhat frazzled.

Chad announced that his grandad had a place about a 10-minute walk from the cinema and he was away. Good one, Chad’s grandad! We stayed up all night at Chad’s grandad’s pad, listening to Licensed to Ill and drinking irresponsibly. Chad told us he’d had sex in the flat the night before with an actual woman!

They’d needed some lubrication, but all Chad could find was his grandad’s Badedas, which unsurprisingly had led to copious pine-fresh genital foam production.

It was the most grown-up story I’d heard up to that point. We put on ‘She’s Crafty’ one more time to celebrate and raided the ashtray to see if there were any smokable butts.

The next morning we staggered out of Chad’s grandad’s pad to get the Tube into school. Before taking the stairs down to Bond Street station, Louis asked us to wait a second, then, with commuters hurrying past, he leaned slightly over the pavement curb and nonchalantly let free an unbroken stream of puke that became known as ‘The Column of Vomit’ when recalled thereafter. Then he looked up, clapped his hands once and pointed the way down to the Tube. I admit that I was impressed. It took us all about three days to fully recover.

So yes, I’m adding the Beastie Boys and John Cusack to my list of people to blame for turning me into a little alcoholic dick, but Bruce Robinson probably played a part, too.

During the Easter break in 1987 Patrick and I went to see Robinson’s film Withnail and I, a tale about two out-of-work actors trying to escape the squalor of their lives in 1960s London by drinking booze, taking drugs and going for a weekend in the country. Keen for something to take our minds off our respective teenage troubles and unprepared for how funny the film was going to be, Patrick and I got a bit hysterical as we watched, though Patrick was more expressive.

By the time an extremely inebriated Withnail was trying to use a washing-up liquid bottle filled with child’s piss to prove to the police he wasn’t guilty of drink driving, Patrick had started rocking back and forth in his cinema seat until the whole row shook. The look of vacant, childlike confusion on Richard E. Grant’s face when Withnail is busted using the pee-pee bottle then caused Patrick to flop right off his seat and begin literally rolling in the aisle (or, indeed, ROFL-ing).

Bruce Robinson presumably trusted that the audience for Withnail and I would understand that the film wasn’t intended as a set of guidelines for a healthy and happy life, but for one 17-year-old short, hairy, overemotional audience member the idea of chemically blocking out an indifferent world with your best friend at your side was very appealing. Sure, the hangovers, paranoia and general sense of decay didn’t look fun, but overall Withnail and I confirmed my growing suspicion that existence was more entertaining once you’d drifted into the arena of the un-sober.

When Paul McGann’s Marwood character finally cleans up his act and breaks away from Withnail’s disastrous, self-pitying orbit, I was thinking, ‘No! Don’t leave! Stay with your friend and keep boozing. That was the fun part.’

Bada Bada Bada Sa-wing Bada!

My anxieties about joining the adult world and being left behind by my friends were further tweaked by Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

There’s an odd scene halfway through the film, out of step with the goofiness elsewhere, when Ferris, Sloane and Cameron visit the Art Institute of Chicago and tag along with a group of much younger children who are there on a school trip, holding hands with them as they’re marched through the gallery by their teacher. The three friends break away to take in the art at their own pace as what sounds like library music from an advert for life insurance plays on the soundtrack (it’s actually an instrumental cover of The Smiths’ ‘Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want’ by The Dream Academy).

Ferris and Sloane kiss in front of some stained glass by Chagall while Cameron reckons with Georges Seurat’s pointillist banger A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. It’s the one with all the people hanging out on a sunny day by the banks of the River Seine in the late 19th century. Top hats and long sleeves for the men, umbrellas and big-booty dresses for the women. Everyone together, everyone alone, see?

Cameron fixates on the little girl near the centre of the painting. She’s the only figure looking directly at the viewer, making a connection the adults around her have ceased to make. Cameron hovers somewhere in between: no longer a child being looked after, not yet an adult in charge of his own life, but an interloper able to see the adult world for what it is: a place as superficial and absurd as the hand signals of stock-exchange workers, fathers who buy expensive cars then never drive them and dead-eyed teachers calling the roll like malfunctioning automatons: ‘Bueller … Bueller … Bueller … Bueller …’

I could certainly relate to that sense of antechamber blues and couldn’t understand why anyone would want to go through into that next big hall from which the sound of serious conversations reverberated, along with the noise of business being done, football crowds, fashion shows, political rallies and hospitals.

And yet Ferris uses all his guile to convince that Eighties movie staple, the snooty maître d’, that he’s Abe Froman, the sausage king of Chicago, just so he can gain access to the stuffy-looking adult playground of the Chez Luis restaurant. I mean, make up your mind. Is it superficial and absurd or do you love it?

I wasn’t crazy about Ferris Bueller’s Day Off on first viewing. I thought Ferris was a bit of a smarmy git and his girlfriend Sloane was exactly the kind of person who would never have given me the time of day in real life, but in Ferris’s friendship with the less adventurous Cameron I saw parallels to my relationship with Joe.

One summery evening during our last term, Cornballs, who had just passed his driving test, turned up at school in his parents’ maroon Volvo 340 and we went for a drive round the West End listening to an Orange Juice compilation. ‘Can you hear me calling from afar, / As you drive uptown in his daddy’s car?’ said one of the songs.

‘This is a very appropriate song,’ I said.

‘I picked it specially,’ smiled Joe. Did that mean he had picked it specially or not?

It was exciting to be driving around with no adults in the car, but it was also disconcerting. Joe, six months older than me, seemed like the cockier, cleverer Ferris to my more timid Cameron quite often, and with him at the wheel of an actual car the contrast was more than usually pronounced.

‘What do you think we’ll be doing in ten years?’ I said at one point.

‘Well, I’m going to be making movies,’ replied Joe.

‘Yeah, but do you think we’ll still be friends?’ I asked, hoping the question didn’t sound as heavily freighted as it was.

‘I don’t know, man. Probably not,’ said Joe as we rounded Trafalgar Square and headed back towards Westminster.

Party Time

As the end of our time at Westminster loomed and the days grew longer and hotter, I was getting used to a strange new grown-up feeling: colossal anticlimax. The supposedly life-ending A-level exams I’d dreaded for so long finally arrived and people from our year drifted into school when they had a paper to sit, buggered off again afterwards and life just carried on. Gradually all the familiar groups I used to bounce between in Yard dwindled and disappeared.

The school organised a ‘Leavers’ Dinner’, but word went round that only goony birds and tragic losers were planning to attend, so I bailed, along with Joe and most of our pals. It was a shame, as a lot of the goony birds were actually very nice and it would have been good to wish them well. Not the tragic losers, though. I couldn’t be seen with them.

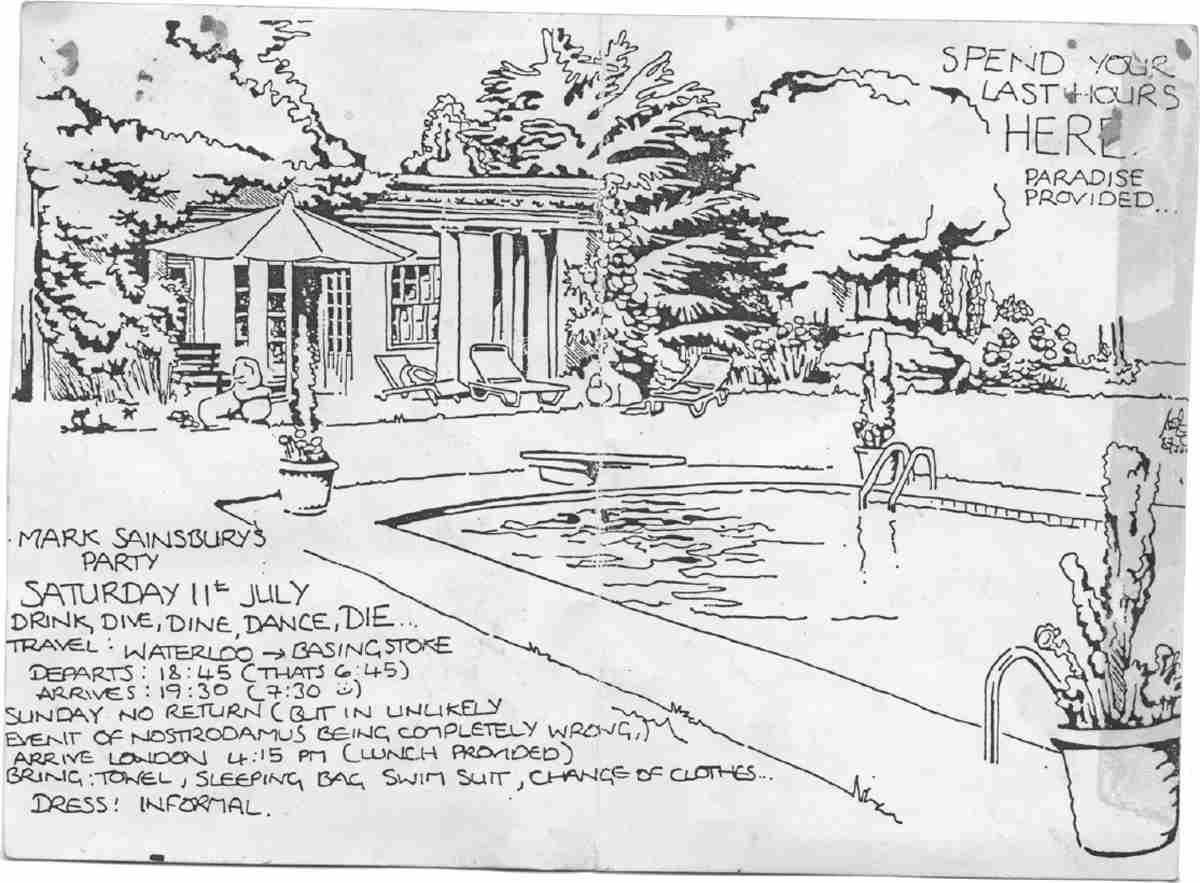

A little focus was restored when Mark announced he was planning a party at his parents’ house in the Hampshire countryside where we had spent many overexcited weekends making stupid videos, riding up and down in the lift and licking famous paintings rather than reckoning with them. This was going to be the party to end all parties, an opportunity to draw a line under our Westminster experience with all the riotous abandon of Animal House and the emotional intensity of The Breakfast Club. That’s how I was thinking about it anyway.

For weeks we discussed the guest list, carefully considering which sixth-form girls were cool and/or we still had a chance of snogging, and which boys should remain uninvited, either because they were too popular, not popular enough or just wankers.

The party was to take place around the pool house at the bottom of the big garden and we agreed it would be best not to invite too many people and instead keep it ‘inner sanctum’.

Despite our efforts to enforce the social borders we’d observed at school, in the summery post-exam euphoria alliances shifted and Mark found himself at pub gatherings that included members of tribes we would have eyed with suspicion back in Yard. A couple of days before the big party Mark explained sheepishly that it was possible he may have got too caught up in the armistice spirit and invited a few members of the Lads who, he said, were actually much cooler than we’d given them credit for. ‘But they’re never going to show up,’ Mark reassured us when we grumbled.

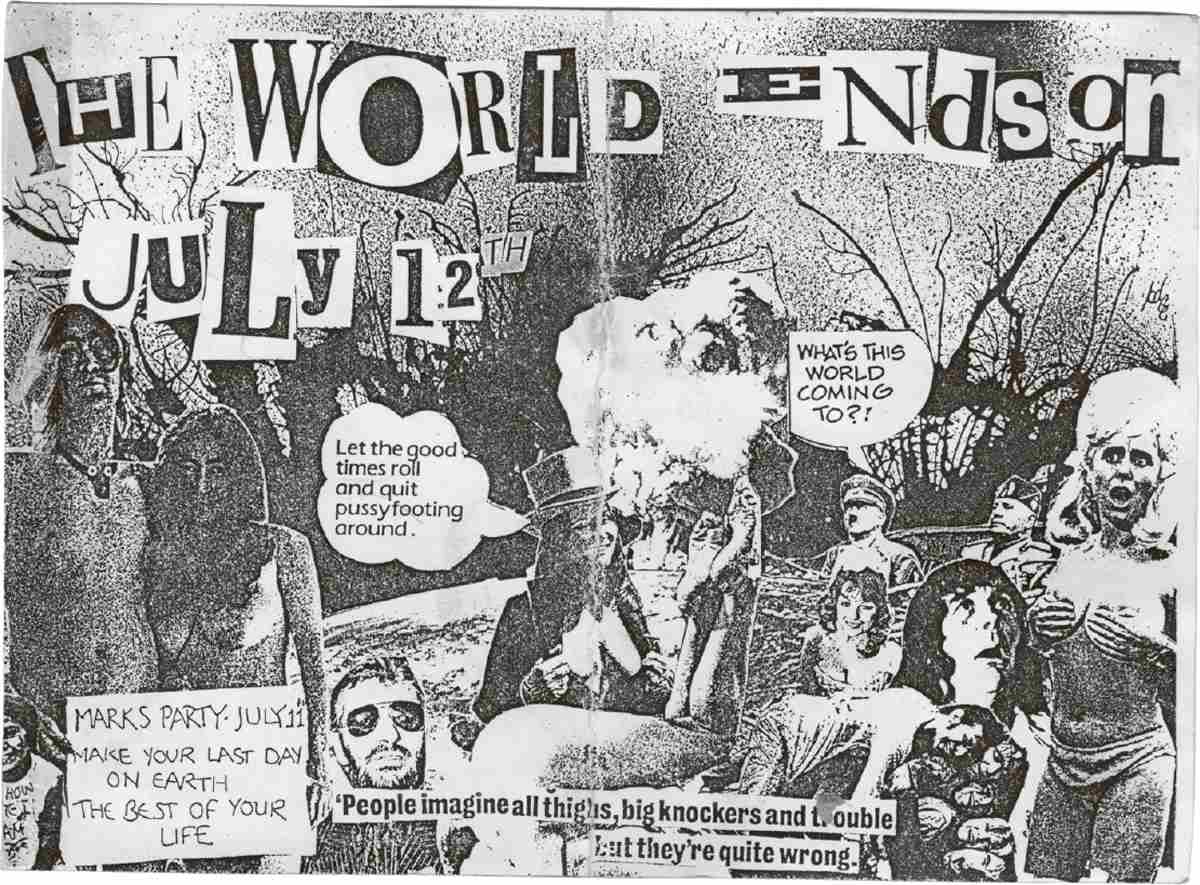

When sexism, privilege, John, Yoko and Hitler collide: the invite I made for the big post-A-level party at Mark’s place.

But of course they showed up.

As usual, helping Mark get the party set up with Joe and Ben the day before had been pure, uncomplicated fun, but as soon as guests started arriving the following evening the pressure to have a good time began to produce the opposite effect. I flitted about distractedly, smoking Marlboro Lights, making gin and tonics and shotgunning the odd can of Budweiser in between having conversations about how weird it felt to have actually left school, from which I would break off to check on the music.

Without record decks, we relied on tape compilations, and there was a lot of switching between Joe’s selections of Orange Juice, James Brown, Haircut 100, George Michael, Prince and Sly & Robbie (whose song ‘Boops (Here to Go)’ had been a favourite in the build-up to exams) and my usual mixes of Bowie, Talking Heads, The Doors, The Cure and Joe Jackson.

Jackson’s album Jumpin’ Jive, which featured covers of swinging jazz numbers from the 1940s, was unexpectedly energising the dance floor when from the shadowy expanse of lawn we heard the sound of teenage boys trying to make their voices as low as possible, and moments later several figures in skinny jeans with indie-band haircuts swaggered from the gloom. The Lads had arrived. They’d even brought a teacher with them who they considered young and groovy. I mean, what the shit?

I nudged Joe and pointed. ‘Lads at 12 O’clock, man.’ Joe groaned, but when some of the more moderate Lads acknowledged us with self-conscious grins I wondered for a moment if Mark had been right and this was the night we’d leave school rivalries behind and celebrate our passage into the adult world together.

Nope.

Off went the Joe Jackson jazz and seconds later the bushes trembled to the sounds of AC/DC’s ‘You Shook Me All Night Long’ followed by much Sisters of Mercy. I looked around hoping for someone to object, but the tide had turned and within half an hour the girls were giggling with the Lads and flirting with the groovy teacher, and our gang was scattered. We had lost control of the pool house.

At one point there was a sudden flurry of activity and I saw Joe leaping Jesse Owens-like over loungers in order to avoid being pushed in the pool by several boisterously laughing Lads. ‘This is like being bullied in my first term,’ said Joe, uncharacteristically flustered.

We went looking for Louis and Ben and found them behind the pool house in a small thicket of trees and bushes, sitting on the ground with Zeb, one of the hippies with the most luxuriant hair.

They had just smoked a joint and were staring at a little boombox playing a song with the refrain ‘Everybody must get stoned’, which I thought made them look a bit too compliant. Joe and I sat down and listened for a while. ‘Who is this?’ I asked.

‘Bob Dylan,’ croaked Louis. It sounded like old-man music to me, but I liked ‘I Want You’. It was a lovely tune and I thought it was brave of Bobbles to confess to stealing a flute from a dancing child with a Chinese suit. ‘I wish every one of his songs didn’t end with him getting his harmonica out, though,’ Louis drawled. Zeb the hippy nodded and smiled.

And that was pretty much the high point of the party to end all parties.

Stern Lectures

Nineteen-eighty-seven was peak stern lecture year for A. Buckles.

Before my exams my house master had done his best to convince me of the need to apply myself more to my studies and less to socialising. ‘You won’t even know those people in five years,’ he reasoned, trying to impress on me the value of thinking long term. It made sense, but try as I might I couldn’t stop feeling that fun in the present was better than security in the future.

A shorter but no less sobering lecture was delivered at the end of the summer on holiday in Greece by the woman I lost my virginity to. A boozy night had ended with us alone on a moonlit beach where, thanks to my lack of experience and an excessively sensitive triggering mechanism, the entire process of one thing leading to another had been over in about 45 seconds.

She was a few years older than me and got impatient when afterwards I sat speechless with embarrassment, staring out to sea. ‘Aren’t you going to say anything?’ she asked.

I looked at her arms in the moonlight. ‘Your arms look nice in the moonlight,’ I ventured.

That went down badly and she bristled. ‘You know, you can’t go through life with that fuck ’em and chuck ’em attitude.’

There was more to her lecture, but that was the headline. I wanted to explain that I didn’t mean to be unfriendly, I was just temporarily immobilised by guilt and shame, though I realised hearing that might not make her feel any less used.

The next day we shook hands and parted on friendly terms, but her words played on a loop in my mind during idle moments for the next few weeks. Fucking followed by chucking was never part of my sexual repertoire thereafter. I was more likely to be guilty of knobbing followed by sobbing.

The next lecture came, unsurprisingly, from Dad.

My A-level results weren’t good enough to get me into the universities I’d applied for and the school had advised sending me to a crammer where I might improve my grades, then reapply. That was going to cost even more money that Dad didn’t have, so I needed to get a job.

The first person I knew who found gainful employment after we left school was Ben. For a few months before he went to drama school, Ben worked as a bartender at a Chicago-themed deep-dish pizza restaurant in a windowless, wood-panelled basement off Regent Street. I was impressed. ‘I don’t think I’m going to stay there very long, though,’ said Ben. ‘If you need money, you should get an interview, Ads. I bet they’d take you.’ I went along the following week.

The restaurant’s assistant manager eyed me as I filled out the application form. ‘So you’re Ben’s friend. Another public school boy. Aren’t you a bit over-qualified to work here?’

‘Well, I did OK at O level,’ I replied earnestly. ‘I mean, I got As in English, art and history, but my A levels weren’t very good. Apparently I’m going to have to re-take Spanish and reapply for university next year.’

‘Right. Well, the good news is you’re not going to need A-level Spanish to clear tables and wash pizza pans. The bar job’s gone, but you could start next week as a busboy.’

‘Great! What’s a busboy?’

‘You clear tables and wash pizza pans.’

‘Oh, OK.’

I worked in restaurants off and on for the next five years.

BOWIE ANNUAL

On my eighteenth birthday Dad gave me some cufflinks and Mum got me a copy of Bowie’s new album, Never Let Me Down. ‘I didn’t know if you already had it,’ she said.

‘Ah. No, I don’t already have it, but that’s because it looks like such a terrible pile of old shit. Just look at the cover. He used to be Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke; now he’s just Hobo in Theatrical Prop Store. And have you seen the video for “Day-in Day-out”? It’s as if he fed the phrases “cool”, “rock star” and “social problems” into Metal Mickey, then used the list Metal Mickey shat out as a treatment. How else does a rich, 40-year-old man decide the best way of dealing with urban deprivation is to tease his hair into a big quiff mullet, dress up like a Ramone that got fired for being too prissy and roller-skate (with elbow pads, of course) past dramatised scenes of homelessness, drug addiction and sexual assault in the mean streets of Los Angeles while pretending to play a no-neck guitar and belting out a single that can’t decide if it’s a protest song or the theme from a Top Gun sequel?’

‘Blimey!’ said Mum. ‘Someone’s been reading the NME. I thought you liked David Bowie.’

‘I do like him, Mum. I love him. I just wish he’d do more of the things I like and less of this cheesy wannabe mainstream shit.’

‘Says the Thompson Twins fan,’ Mum shot back.

‘I went off the Thompson Twins ages ago actually, Mum, but anyway, they were good at being mainstream. That was their job. It’s not supposed to be Bowie’s job.’

‘But, Adam, surely part of the reason you like David Bowie is that he’s always trying something different and taking creative risks? Sometimes those risks pay off and sometimes they don’t. You can’t just turn your back on him because he appears to be having some kind of artistic mid-life crisis. I think one day people will look back on Never Let Me Down and say that its reputation as Bowie’s worst album has more to do with dated production and critical snobbery than it does with the actual songs, some of which – “Glass Spider”, “Time Will Crawl” and “Never Let Me Down”, for example – are perfectly serviceable, despite lyrics that, I grant you, appear to have been written by a drunk fifth-former. You know, there were probably people who thought Ziggy was embarrassing back in 1972.’

‘Ziggy was embarrassing, Mum. But all the daft costumes and make-up look amazing now because he was young and, more importantly, the songs were so good. They were good then and they’ll be good in 1,000 years, but if he and the Spiders had come out with Never Let Me Down, not even Kansai Yamamoto, who as you know designed some of Ziggy’s most striking outfits, would have been able to make Bowie look like anything other than an annoying theatre brat with a band.’

As I’m sure you realise (because I’ve used the same device a number of times in this book), what I actually said when I got the cassette of Never Let Me Down was, ‘Thanks, Mummy, I can’t wait to hear it.’

I ignored the cassette for a few days, then played it out of curiosity. ‘Day-in Day-out’ pretty much summed up the whole thing: noisy, overwrought and insipid. But in a bad way.

On holiday the previous year I’d made friends with another Bowie nut called Rick. A few days after my eighteenth birthday, Rick called saying he had a spare ticket to see Bowie playing live at Wembley Stadium as part of his Glass Spider tour. I didn’t jump at the chance. I wasn’t planning on listening to the studio version of Never Let Me Down again, and I wasn’t keen to flog all the way out to Wembley to watch it being played live. I was also right in the middle of my A levels and my knuckles were supposed to be down, but Rick’s invitation was so kind I didn’t see how I could reasonably refuse it – and anyway, it was still David Bowie, even under the quiff mullet.

On a hot June afternoon, Rick and I weaved through the 70,000-strong crowd at Wembley Stadium towards the giant complex of vaguely arachnoid scaffolding at the far end. It was still broad daylight so the lighting that was meant to bring to life the ‘spider’ squatting over the stage wasn’t yet noticeable and the overall atmosphere was genial but hardly electric.

As we shuffled past groups of people chatting about having seen Bowie at Live Aid or wondering whether he would play ‘Let’s Dance’, I could feel my snobbery levels rising dangerously. ‘How many of these “fans” regularly think deep thoughts and shed a tear as they listen to side two of Low on their headphones?’ I wondered. ‘Less than 4 per cent, I reckon. I imagine most of this crowd would probably prefer a football match to an audience with the man who sang “Letter to Hermione”.’

There was a cheer as a figure arrived on stage and began playing a noodly, atonal guitar solo. The big video screens showed a close-up of the guitarist’s face and I looked over at Rick. It was Carlos Alomar – along with Mick Ronson, Bowie’s trustiest sideman. ‘Carlos Alomar!’ we grinned. Suddenly Alomar’s atonal squeals were interrupted by a voice over the PA that shouted, ‘SHUT UP!’ Time to look at Rick again, because that was Bowie shouting ‘SHUT UP!’ the way he had over Robert Fripp’s guitar at the end of ‘It’s No Game’, the opening track from Scary Monsters. ‘OK, maybe this show is going to be cool after all,’ I thought.

That’s when a load of extras from Duran Duran’s ‘Wild Boys’ video dropped onto the stage on ropes and began walking over to things emphatically, striking poses and shouting lines like, ‘We are the scum children! What have you done with our future?’

RAMBLE

I just watched some footage of the Glass Spider tour on YouTube and they didn’t shout, ‘We are the scum children! What have you done with our future?’ Mainly they were shouting lines from ‘Up the Hill Backwards’ in a way that, at the time, made me hope we were going to hear ‘Up the Hill Backwards’, but no such luck. Also, they looked more like the Kids from Fame trying to be edgy than extras from the ‘Wild Boys’ video.

The show was full of references to parts of Bowie’s career that he knew fans like me and Rick would pick up on. Unfortunately, it was also full of Never Let Me Down, all but two tracks of which were played that night. He threw us a few bones, though, and we were treated to solid versions of ‘All the Madmen’, ‘Big Brother’ and one of my favourite tracks from Heroes, the woozy, vaguely Middle Eastern-sounding ‘Sons of the Silent Age’.

Perhaps worried that it was too weird for the ‘Let’s Dance’ brigade, Bowie couldn’t resist sprinkling some theatre dust over ‘Sons of the Silent Age’, and while Peter Frampton took over singing on the choruses, a woman stood in a pair of ski boots attached to planks, swaying forwards and backwards as Zavid pretended to be controlling her movements with magical hand gesturez.

What more could you want … except maybe less?

My cassette of Never Let Me Down didn’t re-emerge until Joe and I went travelling round Europe towards the end of that summer, when I stuffed it in my backpack, anticipating the fun of regaling Cornballs with choice moments of terribleness: the long spoken intro to ‘Glass Spider’ (‘Tiny wails, tiny cries’), the song ‘Too Dizzy’, which sounded like the theme to a daytime TV interior decoration show, and the section on ‘Shining Star (Makin’ My Love)’, in which Bowie and Mickey Rourke interrupt what sounds like a Pepsi & Shirlie B-side to exchange a series of raps about a hired killer who ‘blew heads outta shape in the name of Trotsky, Sinn-Féin, Hitler cashdown’.

But I hadn’t realised how much of our Euro trip would be spent sitting outside toilets on packed, slow-moving trains or going out of our minds with boredom and hunger on overnight ferries, and when the conversation dried up the only thing that stopped me jumping overboard was my Walkman. With space at a premium, I had packed just a handful of cassettes, and when I’d overdosed on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, the Stones’ Through the Past, Darkly and my 120-minute compilation of Super Summer Sounds, I eventually turned to Never Let Me Down.

No, I didn’t suddenly realise I’d been wrong about it. It was still shit, but it was like the shit of one of your children: somehow less offensive than other shit because it came out of someone you love. ‘Shining Star (Makin’ My Love)’ started to sound like quite a good Pepsi & Shirlie B-side and rumbling through the outskirts of Rome on a hot coach I realised I was also enjoying the daytime TV bounce of ‘Too Dizzy’, despite an oddly threatening tone of jealous rage in the lyrics: ‘I’m not trying to lose control, / But you’re just pushing for a fight!’

‘Not very Zavid,’ I thought.

RAMBLE

Bowie removed ‘Too Dizzy’ from subsequent editions of Never Let Me Down and it’s generally regarded as one of the worst songs he ever recorded. I still like it.

Even ‘Zeroes’ – a song whose crap, sitar-soaked, sub-Beatles sound was made especially offensive by the ‘Heroes’ pun – ended up being a song I love to this day. Though it’s possible I love it in much the same way as I love scratching my nuts, picking my nose and smelling my farts.