My extraordinary work in the field of table-clearing eventually led to me being invited to join the special forces of the restaurant world: the bartenders. Sure, the servers made more money, but the bar staff had their own separate domain that only they could access: an elevated section near the entrance where they stood protected behind their mahogany bulwark in smart shirts, bow ties and waistcoats, looking down over the restaurant floor.

Not long after I completed my training, Lenny the bar manager took his six-person team to see the Tom Cruise film Cocktail (or, as Joe referred to it, ‘The Tale of a Cock’). Lenny was hoping Cocktail would inspire us to enliven Happy Hour at the pizza restaurant with the kind of bottle-flippin’, glass-spinnin’, high-fivin’ ‘flair’ demonstrated in the film by bartenders Coughlin and Flanagan. We tried to incorporate a few of their moves, but the results, like some of the cocktails, were mixed, and left us, like some of the other cocktails, shaken.

Glass bottle shelves were smashed by flying tumblers, customers were lashed with arcs of cherry liqueur, and one busy Friday night an attempt to do a cool dance to ‘Hippy Hippy Shake’ while re-stocking glasses ended with me slipping and bringing down about 50 highballs. They shattered in a jagged heap and I landed palms down on the lot. I spent the rest of the evening getting stitches at St Thomas’s A&E before meeting my workmates for a beer and a delicate high five at the end of the night.

The injury was one of several signs that it was finally time for me to leave the pizza restaurant and work elsewhere until it was my turn to be pushed around in a wheelbarrow while dressed as a baby, followed by pints of lager and lime in the Nelson Mandela bar at Warwick University. Despite the ‘Cancer’ and Cocktail incidents, my boss Sally gave me a good reference and I got a job behind the bar at another subterranean American-style hang-out, this time in Dover Street opposite The Ritz hotel.

Wave of New Relations

The Service Point was the section at the end of the bar where servers came to pick up drinks orders for their tables. Most of the bartenders preferred working on the main bar to working ‘Point’, because generally you got better tips from the customers than the servers. I liked the Service Point because it meant I got to see Miriam.

I had just celebrated my twentieth birthday. Miriam was 24 and seemed impossibly sophisticated. She was the first person I’d met who had taken Ecstasy, and after stressful restaurant shifts Miriam might head over to the Wag Club in Soho and spend the rest of the night weaving her long hands through the sweaty air to the sounds of Soul II Soul, Yazz, Inner City, Bomb the Bass and S’Express.

Other nights she’d come out with us non-ravers and we’d sit around in a late-night bar, drinking, smoking and talking about all the good stuff: restaurant politics, art and heartbreak. She was a good mix. Fierce and flaky. Concerned and carefree. Right on and non-judgemental. I heard my first dawn chorus after one of those late-night bar sessions. ‘Look at me,’ I thought on the night bus. ‘I’m Jimmy Coming Home at Sunrise.’

Despite my fears that we were drifting away from one another, I still got to see my school gang whenever they were back in London. Joe and I went over to Louis’s place one evening and I invited Miriam along, too. We’d all recently seen Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing and rehashed a version of the conversation that all good Guardian and Time Out readers had to have about it. Then Joe put on Public Enemy and I wondered if Miriam thought we were trying a bit too hard.

As Cornballs and Louis started deconstructing the lyrics to ‘Fight the Power’, Miriam led me to another room and it seemed appropriate for us to get undressed. ‘Ooh, Gustav Klimt woman,’ I thought. ‘She doesn’t shave her armpits. Hope that means she won’t mind my hairy back.’ In fact, Miriam was more focused on my head. At one point in the proceedings she yanked my hair with such force I didn’t know whether to cry out in pain or laugh at the over-the-top Betty Blue-ness of it.

Once we’d both stopped trying so hard, we realised we got on well and the rest of the summer was spent hanging around with Miriam and her grown-up friends. For a long time, my idea of a perfect Sunday had been waking up at midday and watching Network 7 in bed with several bowls of cereal before my mum knocked on the door about 2 p.m. and asked if I was planning on getting up at any point. Now that Miriam was around, my routines got more highbrow. At least, there was a wine bar in Clapham that we went to quite a bit and we saw several exhibitions at the ICA and pretended we understood them.

I showed Miriam some of my drawings (though not the one of the JOEADZ corporate tower) and she was impressed. We went to some local life-drawing classes and sometimes we’d go back to her room afterwards and draw each other – and yes, it was exactly like Titanic, but sometimes I was Kate and she was Leonardo.

When we were drawing together we were perfectly in sync, but our temperamental differences started to show when it came to the music we preferred. For Miriam, that was anything that sounded good on a dance floor where she could lose herself. For me, it was more likely to be music that soundtracked my angst. But in a fun way.

Intimidated by Pixies

I’d bought the first Pixies album, Surfer Rosa, when it came out the previous year, in March 1988. They were playing it downstairs in the King’s Road branch of Our Price and I thought it sounded like music for tough people, so I asked the guy at the counter what it was. ‘Pixies,’ he grunted, probably surprised that a fresh-faced fellow in a pink collarless shirt with a lavatory-brush hairdo might be interested in such uncompromising music.

‘Cool. I’ll take it,’ I said, sliding Jimmy Plastic over the counter.

I listened to Surfer Rosa as I walked home, but it sounded much less fun than it had in Our Price. Back in my room, I studied the cover photograph of a woman in a big flamenco skirt standing against a wall decorated with fairy lights, a crucifix and the broken neck of a guitar. I didn’t register any of those things initially because she was also topless. As it was a cassette inlay, not a vinyl sleeve, which would have been better for studying purposes, I had to really squint to appreciate the impressive detail.

The sleeve gave no clue as to what the band looked like. The artwork and the harsh sound of the music made me imagine some druggy types in a dive bar on the Mexican border. I imagined Pixies probably wore tight, studded leathers and lit up strong joints between shots of Jack Daniel’s and told straights like me to go fuck themselves. Well, I don’t appreciate being spoken to like that, so the next day I walked back to Our Price and asked for my money back.

‘Didn’t you like it?’ said the same counter guy.

‘Not really my thing,’ I mumbled, trying hard not to make it too obvious that I had been intimidated by Pixies.

A year later Pixies released their second album, Doolittle. I had seen the video for ‘Here Comes Your Man’ on The ITV Chart Show and the band performing ‘Monkey Gone to Heaven’ on BBC Two’s culture programme The Late Show and I was surprised to find they didn’t look intimidating at all. In fact, their female bassist, whose voice on Surfer Rosa had conjured images of an etiolated drug vampire, was actually adorably smiley and even looked approachable. OK, so in real life she did go through a bit of a drug vampire phase and she may well have told me to fuck off if I had ever approached her, but still, she seemed fantastic.

More important than any of that was the music, which was catchy, albeit with a hard-edged intensity that made it tremendous. Doolittle went round and round on my Walkman that summer and was the soundtrack to becoming friends with Miriam. The first time I cycled up to her place in Newington Green I had to keep stopping to rewind a song whose lyric celebrated being ‘on a wave of new relations’. ‘Like me,’ I thought. I later discovered the song was actually called ‘Wave of Mutilation’.

I went back and bought Surfer Rosa again, along with the first Pixies EP, Come On Pilgrim, which I could only get on vinyl. There was no topless flamenco woman on that cover, just a fellow with an unusually hairy back. The arrival of hair clumps on my own back was making me feel like Brundlefly, but the Come On Pilgrim man convinced me I didn’t have anything to complain about. Pixies kept ticking all the right boxes.

In the years that followed it was gratifying to see their sound recognised as an important influence on rock luminaries such as Kurt Cobain, PJ Harvey and Radiohead, but I never thought they got enough credit for their brave, positive stance on hairy backs.

Gawain’s World

After two years out of education, the thought of going to university filled me with gloom. I would miss my restaurant friends, and the prospect of seeing less of Miriam was a particular kick in the willy. I had made it through the whole summer without saying ‘I love you’ because I felt I’d said it too much in the past and now I was determined not to spoil the fun. But when Miriam told me tearfully that she’d miss me at a farewell get-together, I took it as my cue to be honest. Instant fun spoiler.

The following week I sat in my tiny halls-of-residence box room at Warwick University and resolved to give undergraduate life my best shot. But thoughts of Miriam, the ubiquitous funk of cheese toasties and the sound of Green by R.E.M. drifting out of every student dorm and every bar as if to declare, Life of Brian-style, ‘Yes! We are all individuals!’ was making it difficult to be positive. ‘Try to be less superficial, Buckles,’ I thought. ‘Concentrate on the English and American literature.’

For some reason, possibly because I hadn’t properly investigated the actual course, I thought the English literature part might be sidelined in favour of free-form discussions of groovy Americans like Kerouak, Kesey and Ginsberg. We’d argue about them animatedly over coffee and cigarettes, then continue the conversation late into the night in one of Coventry’s many excellent bars.

As it turned out, the whole of my first term at Warwick was given over to studying Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, an alliterative poem written in fourteenth-century Middle English. At first, I found Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to be a fairly standard load of impenetrably boring old shit that reminded me of how much I’d hated studying Chaucer at school. However, after several tutor groups I started to think Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was actually the biggest load of impenetrably boring old shit I’d ever brushed up against in my life.

I knew the problem lay with me and that if only I could concentrate for long enough, the hidden joys of the ancient text would reveal themselves like images of leaping dolphins in a Magic Eye picture. But I was never any good with Magic Eye pictures (also, they weren’t around until 1993). So I trudged about the concrete campus trying not to think of Miriam, and embraced every available opportunity for extracurricular distraction.

After years of being terrified by the idea of psychedelic drugs, the drabness of university life emboldened me one night to say ‘Yes’, albeit nervously, when one of the people I’d started spending time with suggested we take magic mushrooms. My friend led the way to a remote part of the campus and in a messy, low-lit room I told the man in the Wonderstuff T-shirt with the ziplock toadstool bag, ‘I don’t want to get off my head. I just want to get a bit giggly.’

He handed me some toast piled with soggy mushroom flesh and said, ‘That’ll make you giggly.’

A couple of hours later I was wandering the university grounds with a group of fellow mushroom enthusiasts, marvelling at the details of leaves, lights, the roughness of brick and the smoothness of metal.

Occasionally there was a bit of giggling. When everything started to look drab again, I assumed the experience had concluded safely, so I said goodnight and went back to my study, ready to turn in. That’s when things started to go wrong.

Lying in bed with my headphones on, I pressed play on my new Discman and, as the long opening track from Astral Weeks enveloped me in its familiar twinkling warmth, I smiled to myself. ‘This is fun,’ I thought. ‘I took mushrooms and didn’t have a terrible time. I’m Jimmy Psychedelic Drugs.’ But halfway through the second track, ‘Beside You’, Van’s magical musical forest began to darken.

There’s a passage in ‘Beside You’ when the rambling poetry gives way to the more prosaic: ‘You breathe in, you breathe out, / You breathe in, you breathe out, / You breathe in, you breathe out, / You breathe in, you breathe out, / And you’re HIIIIIIIIGH!!!!!’ and as if responding to Van’s command, I began to breathe in and breathe out until by the end of the line I felt I was being yanked out of myself and lifted into airless space where images of faces began morphing into one another uncontrollably.

After a few minutes of trying to enjoy what looked like a CGI sequence from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, I found that the sheer relentlessness of the imagery was beginning to make me anxious, so I pressed stop on the Discman, sat up, turned on the light, went over to the sink and splashed water on my face. I looked up at my reflection in the mirror and my blood froze. There was someone else looking back at me.

I knew it must be me. He looked like me – handsome, intelligent, friendly but not ingratiating – but I didn’t feel connected to him. It was like looking at a clone. Beginning to panic, I tried splashing more water on my face and opened my study window to let in the chilly October air, but when I turned back to the mirror the clone was still there. I didn’t feel physically intoxicated, and the voice in my head sounded the way it usually did, but I knew the mushrooms had knocked an important cable loose and now I was frightened that it might never be repatched.

Pulling on some clothes, I went out to one of the communal toilets in the corridor, hoping the ordinariness of taking a pee would help snap me out of whatever I was experiencing, but when I went to fetch out the old chap I was very sad to find him shrunk to the size of an acorn. OK, so it was more like a large acorn, but still, my knob was smaller than it had been since I was about four. So now, in addition to fucking my mind, I had broken my Cøken.

In the end I went and knocked on the door of a friend’s study and he let me sleep on his floor. It was uncomfortable for both of us, but I was grateful. I was just too freaked out to be alone.

The next day my penis returned to its regular size and I reconnected with my reflection, but my time at Warwick failed to improve. My grant application had been refused, but Dad was scrabbling around trying to keep my brother at Haileybury, so financially I was on my own. I had opened three bank accounts at the beginning of term and had been living off the £200 student overdraft they each offered, but now that money was gone. I could have found a job locally, but I told myself I’d make more money in less time if I travelled back to London on weekends and pulled a few bartending shifts, which meant I could also see Miriam and the rest of my friends, too. So that’s what I did.

Miriam had been able to put the ‘I love you’ incident behind her and over the course of several weekend visits to London we picked up where we’d left off. The more fun I had in London, however, the harder it was to return to concrete Warwick, my tiny study and Sir Gawain.

Then one afternoon, working on the first big Gawain essay we’d been set, I had an epiphany. For several days I’d been struggling to write something that sounded scholarly and ‘legit’, when a passage in the book reminded me of a scene in Withnail and I. It was the bit in the flat near the beginning when Withnail’s reading out an article about a shot-putter called Jeff Wode and he starts imagining what it would be like to be threatened by him: ‘I’m gonna pull your head off.’ ‘No, please don’t pull my head off.’ ‘I’m gonna pull your head off because I don’t like your head.’ There was something about the baldness of those lines I’d always liked, and I realised nothing was stopping me from writing my Gawain essay with a similar colloquial directness, as long as I stayed on topic, of course. I started the essay again and this time it flowed out of me in just a few hours.

A week later the essays were marked and our tutor was handing them back to the group. Overall, the standard was poor, she said. ‘You’re going to need to raise your game,’ she told some of the other students, but I still hadn’t got my essay back. ‘Adam, would you mind staying behind?’ she said. ‘I’d like to talk to you about your essay afterwards, if that’s all right.’

‘Of course,’ I said and waited for the other students to file out of the room.

‘I didn’t want to say this in front of the others because it wouldn’t have been fair to them and I didn’t want to embarrass you, but your Gawain essay was one of the most refreshing and insightful pieces of work I’ve seen since I’ve been teaching this course. You made all the relevant points, but you did it in a way that was funny, direct and genuinely surprising. So, thank you. In fact, I was wondering if you’d consider reading it aloud at our next tutorial. I think the other students would find it really useful.’

I swear to you, that’s what I thought my tutor was going to say. Instead, she said, ‘Have I done something to offend you?’

I asked her what she meant. ‘Well, I assumed you were angry with me for some reason. Why would you hand in this essay otherwise?’

‘Oh. I thought it was good. I thought you were going to say you liked it,’ I replied, genuinely bewildered.

‘This essay is an insult and I’m not going to mark it. I want you to go away and write a proper one now and hand it in to me tonight. Then we can forget all about this and move on.’

‘Hey, it’s good to see you, Adam,’ said Mum when I got back to Clapham. ‘How’s university going? I want to hear all about it.’

‘Actually, Mum, I’ve left university, and I’m not going back.’

My Gawain essay might well have been bad, even insultingly bad, but my tutor’s reaction had convinced me once and for all that I was not where I was supposed to be. So, instead of plunging back into Gawain with a new attitude, which I considered doing for at least a couple of minutes, I went to see the dean of students and explained that life at Warwick had become unsustainable.

Mum wept. Dad sighed. Even Miriam looked a little apprehensive that I was back in London full time. Though she was pleased to see me, she knew I was liable to say ‘I love you’ at any moment and nobody wanted that. Miriam’s big news was that she had decided to apply for art school and she suggested I do the same. ‘It’s weird you didn’t go in the first place,’ she said, and I realised she was right.

I got a portfolio together and applied to the most exciting-looking art schools I could find, including St Martins, where Zac was studying. I was worried about Miriam, though. I felt she lacked some of the formal skills and imaginative flair that characterised my work and it would be tough for her to get into the kinds of prestigious art institutions that would be begging me to attend. Needless to say, she got into her first choice while I was rejected by all but one of mine. I only needed to get into one, though, and my four years at art school set me on the path to doing everything I’ve done since then, for better or worse.

On New Year’s Eve 1989 I cycled over to Louis’s place where he and his girlfriend Sarah were hanging out with Joe and Zac and getting stoned. We sat about and sang along with Zac and Joe as they played funny songs on the guitar. The Surprise Rhyme Song, The Robert De Niro Calypso and a country song about someone called Roscoe H. Spellgood who liked to go a long way in a short time. ‘That’s why I increase my velocity when possible, cos speed equals distance over time,’ sang Zac, and the rest of us harmonised.

But I wanted to drink beers, not get stoned, so soon after 11 p.m. I decided to cycle into the West End where Miriam was doing a shift, thinking it would be good to be with her as 1990 dawned. But I misjudged how long it would take me to get there and in the end I was just entering the celebratory mêlée in Piccadilly Circus as the clock struck midnight and a drunk reveller pushed me off my bike. By the time I got to the restaurant where Miriam was working, she was having fun, I was pissed off and we ended up arguing.

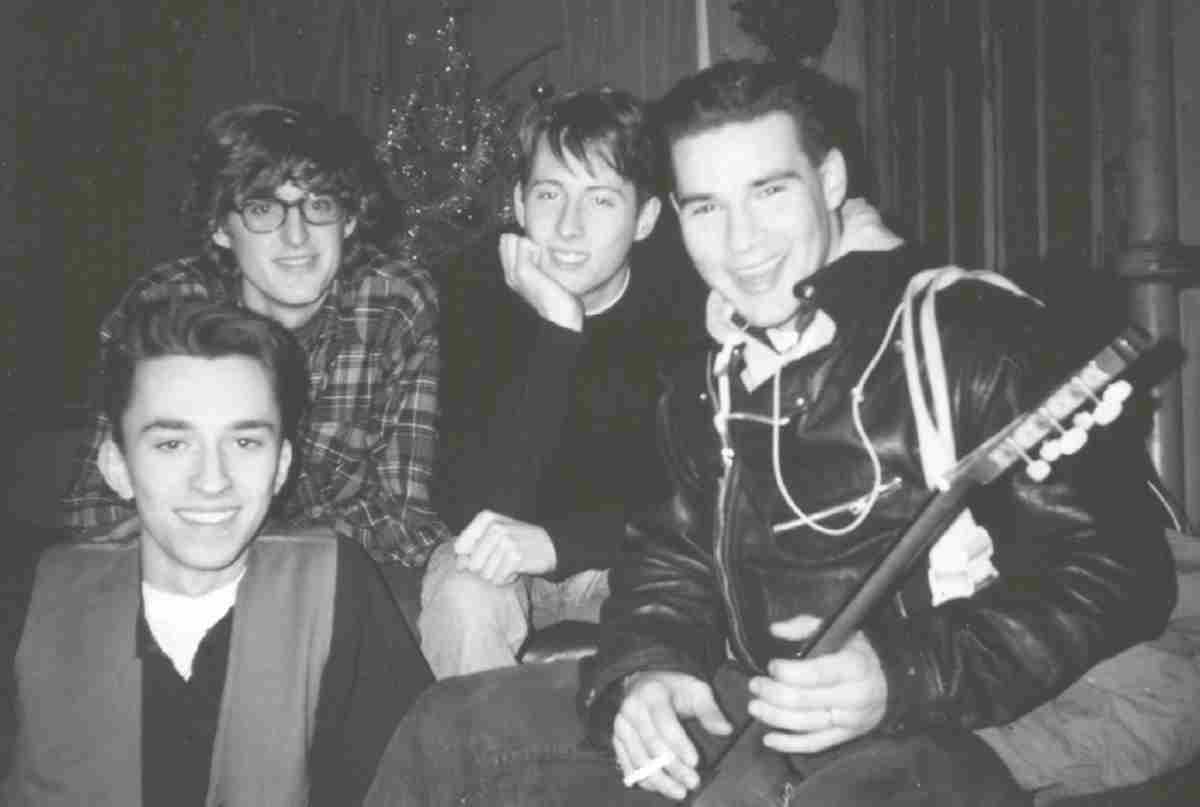

Before I’d left South London that night, Sarah had taken a photo of Louis, Zac, Joe and me with my Instamatic camera. We look so positive and happy. It’s strange to remember how much doubt and worry there was sloshing around. As for Miriam, we had a few more great months before I dropped my three favourite torpedoes and our boat finally went down.

L to R: Zac Sandler, Louis Theroux, Joe Cornish and me at Louis’s house, New Year’s Eve, 1989.

Ten years after I asked Joe if he thought we’d still be friends in ten years, we were making The Adam and Joe Show together and Zac was helping us, contributing songs, models and cartoons. No idea what happened to Louis.

BOWIE ANNUAL

‘David Bowie “back on course” with Tin Machine’ said the cover of Q magazine in June 1989. I was reading the Bowie interview at the restaurant one afternoon before starting my bar shift and, though I didn’t much like his new beard, Zavid was making all the right noizes.

He’d lost his way with his last three albums, he said. Yes, David, I agree! He wanted to pick up where he’d left off with Scary Monsters, he said. Yes, David, Scary Monsters! That’s where we fell in love, back in the art room at boarding school, remember? He’d been inspired to return to a more stripped-down rock sound after listening to Pixies, he said. Fucking hell, David, YES! I love Pixies, too! Uh-oh … Looks like I’m excited about the new Bowie album.

I bought Tin Machine from Tower Records in Piccadilly Circus on my way into work the next day and when the shift was over I listened to it as I walked to Trafalgar Square to get the night bus. Two tracks in, I was thinking, ‘Have I done something to offend you?’

Everything about the record struck me as an unwelcome exercise in trying to be one of the lads. Manly men in suits playing manly blues rock with a manly nod to the jagged guitar sound of the Pixies, but with none of the vitality. The title track especially sounded like a strange rock’n’roll nursery rhyme written by a grumpy dad at a music festival. ‘Tin machine, / Tin Machine, / Take me anywhere, / Somewhere without alcohol, / Or goons with muddy hair.’

I wondered if the name ‘Tin Machine’ was inspired by the Pixies song ‘Bone Machine’? If so, that was the problem in a nutshell.

What is a Bone Machine? A machine for crushing bones? A machine made from bones? A machine inside someone’s bones? It’s disturbing David Lynchy shit whichever way you slice it. But a Tin Machine? That’s just a machine made of metal. A lot of machines are made of metal. They tend not to be made of tin because tin is crap and would make the machine more likely to fall apart.

But maybe I was being too hard on David and, not for the first time, too literal. A couple of the songs on Tin Machine were actually pretty good. ‘Prisoner of Love’ had the same tone of grand, romantic desolation that I heard in ‘Because You’re Young’, a song I always liked from Scary Monsters. ‘I Can’t Read’ also stirred the emotions with its drunk punk swagger and was the closest the record got to being as edgy and interesting as some of its influences. But that wasn’t very close.

I really put in the hours with Tin Machine, but it was competing for my valuable time with albums I’d recently discovered by The Stone Roses, De La Soul, Magazine, Grace Jones, XTC, Public Enemy, The Velvet Underground and of course Pixies, so repeated wading through po-faced rock sludge for two serviceable tracks just didn’t add up. Even The Traveling Wilburys had more pep. Way more, in fact.

‘I’m zorry you feel that way, son,’ said imaginary Bowie. ‘But to be honest with you, I don’t care any more. Or maybe I care too much and that’s why I’m making a machine out of tin – a machine designed to collapse on itself, thereby enabling me to pop it in the rezycling bin and move on with my career without constantly being made to feel I’m dizappointing people like you. You and me have both changed a lot in the last ten years. We’ve had some good times. We’ve had some bad times. And we’ve had some really embarrassing times, but now I think it might be best for both of us if we zpent some time apart. You can check in on me now and then and see what I’ve been up to if you like, but if you see me in a corridor backstage after a show for BBC Radio 2 at Maida Vale Studios, don’t be surprised if I make a beeline for a more zuccessful comedian.’

Fair enough.

My pre-ordered copy of Bowie’s last album, Blackstar, arrived on 11 January 2016, just hours after I’d read the news of his death. I’d heard the singles and a couple of the older tracks already and thought they were good, but now that he was gone everything on the album sounded as mysterious, sad and uplifting as his music had back when I was a boy. For about two weeks Blackstar was the only music I could listen to. It gave shape to a confusion of feelings about Bowie, about Dad, about getting older, about all of it, but the final track, ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’, was the one I kept coming back to.

Mostly the song seemed to be a rumination on mortality, but as ever with Bowie, it contained little references to his career that catapulted me back to my study at school, not knowing how to feel about so many things and thinking as I listened to his records, ‘Well, maybe I feel like that.’

‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ also seemed to be a final word on the game Zavid had played all his life. A game that was part high art and part junk. Part truth and part bullshit. Part meaningful connection and part selfish isolation. Part original and part stolen (I’m just going to do a few more of these and then I’ll stop). Part Hero and part Zero. Part one and part two. Part Glass Spider and part Sparse Glider. OK, you get the idea.

It couldn’t always have been an easy or rewarding game for him to play, but I dare say he got more out of it than just money, back pats and blowjobs. I hope so.