My adolescence fell squarely in the 1980s and, for better or worse, the culture I consumed in that decade has played a significant part in defining my life ever since.

I look back at some of those Eighties influences with fondness and admiration for my good taste, but others evoke the sadness my dad felt about what I chose to fill my days with. To him it seemed as though I was living on a diet of worthless junk that would clog my intellectual arteries and lead to possible art failure. Now, in doubt-filled middle age, bringing up my own children as growing sections of society revise their attitudes to much of the culture and the values I grew up with, I often find myself thinking Dad might have had a point.

Where are the books? The trips to galleries or museums? The theatre? Where is the engagement with politics and social issues? The work by people other than men from the US or the UK? And when something genuinely worthwhile was put in front of me, even if eventually I ended up appreciating it, my initial response was usually to scrunch up my face in disgust, like a baby tasting caviar.

A decade of expensive private education, and all I had to show for it was a love of left-field pop music, an intimate familiarity with TV and mainstream cinema and the ability to quote a few Eddie Murphy routines (I use the word ‘quote’ loosely; basically I would fill any conversational lull by saying, ‘I got an ice cream and you ain’t got one’, ‘Goonie-goo-goo, with a G.I. Joe up his ass’ or ‘SERIOOOOO!’

Join me, then, as I revisit a few of the adolescent moments, along with their audio-visual accompaniment, that helped make me the towering genius I am today.

Pits, Pendulums and Dirigibles

The year 1980 began with me aged ten and starting my second year at the co-ed boarding school in Sussex that Dad always referred to as ‘The Reformatory’. I no longer cried when they dropped me off there but would still rather have been at home, eating Penguin bars and McDonald’s quarter-pounders and chips in front of The Dukes of Hazzard, Metal Mickey and Fantasy Island. And CHiPs. The cultural treats on offer at school may have been more nutritious, but they were harder to digest.

Most nights, when everyone was in bed, stories would play out over the PA system. Sometimes it was something fun like James and the Giant Peach, The Colditz Story, The Hobbit or some Greek myths, but on other nights we’d be treated to a profoundly upsetting helping of horror from M.R. James or, worse, Edgar Allen Poe. It was a kind of audiobook Russian roulette and you never knew if the chamber was loaded until the PA crackled to life and the story began.

I lay in my bunk, wide-eyed with dread in case the words ‘I was sick – sick unto death with that long agony’ came through the tannoy, because that meant it was ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’ time, and the next half-hour of homesick gloom was further darkened by Edgar Allen Poe’s story of physical and psychological torture during the Spanish Inquisition. ‘The Black Cat’ and ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ would follow, by the end of which one or two children in every dormitory would be sobbing softly, and in the junior dormitories, wailing loudly. And that was just the bedtime stories.

One afternoon every weekend a film was projected onto the wall of the gymnasium. In the days before 24-hour mobile entertainment was considered a basic human right, these film showings were a big deal and I could be found sitting cross-legged on the wooden floor of the gym, regardless of what was playing. It was a varied programme that during my time included The Four Feathers, Kes, Capricorn One, Bugsy Malone, The Thief of Bagdad, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Duel, One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing, Ring of Bright Water, Jaws, Hooper, Smokey and the Bandit and Smokey and the Bandit Ride Again (as the Eighties dawned, Burt Reynolds was still considered one of cinema’s most alluring cishet fuckboys).

Along with lashings of Burt, they also served up some of the biggest and stupidest disaster films of the Seventies, and my first sense of how much could go wrong in the world came via school gym performances of The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, Meteor and the Airport series. But nothing took a giant shit on my psyche quite like The Hindenburg and The Cassandra Crossing.

The Hindenburg was basically a ‘Whogonnadunnit’ that took place on a luxurious passenger airship in 1937. George C. Scott played a German colonel who has been warned of a plot to blow up the dirigible. Unaware that the film was loosely inspired by historical events, I expected George to foil the plot in the nick of time and prevent the airship from exploding. SPOILER ALERT: he doesn’t.

The final section of the film switched from colour to black and white, intercutting between newsreel footage of the actual Hindenburg’s fiery skeleton sinking to the airfield, with shots of various characters staggering from the wreckage, some horribly burned. Presumably the lack of colour was supposed to take the edge off the horror, but not for ten-year-old Buckles. I sat, heart beating fast, as Herbert Morrison’s famous commentary tearfully mourned ‘The humanity!’

RAMBLE

For several years in my twenties I developed a fear of flying, and every time I boarded a plane, images of the crumpled Hindenburg would pop into my head along with the phrase ‘twisted mass of girders’. (If you’re reading this on a plane, sorry, but honestly, you’re going to be fine. However, in the unlikely event that something does happen, just ask someone to send in the charred remains of your boarding pass and I’ll personally issue a full refund. For the book that is, not the flight.)

In The Cassandra Crossing, a terrorist carrying a deadly plague virus created by the Americans for germ warfare boards a train travelling across Europe, where he infects a load of passengers before the authorities reroute the train across a rickety bridge. Richard Harris, Sophia Loren and O.J. Simpson do their best to avert disaster. SPOILER ALERT: they don’t.

I can trace a number of my biggest fears back to that Sunday-afternoon screening of The Cassandra Crossing and to this day I do my best to avoid deadly viruses, quarantines enforced by armed men in scary hazmat suits, trains that plunge off rickety bridges into ravines and O.J. Simpson.

As I was an easily confused ten-year-old without parents on hand to clarify perplexing moments in films like this, it was left to other equally clueless ten-year-olds to concoct explanations. For example, my friends and I decided that when, in one scene, the plague-carrying terrorist sneezed on a bowl of rice, he was in fact vomiting maggots, thereby adding three more items to my list of Worsties: vomiting, maggots and vomiting maggots.

Obligatory Star Wars Bit

By the time The Empire Strikes Back was released in May 1980, everything Star Wars-related made me vibrate with visceral joy.

Two years earlier, when we were living in Wales, Mum had driven me and my sister all the way to the West End of London to see the first Star Wars film (if you’re thinking, ‘Well actually, Buckles, it was Episode IV – A New Hope,’ then please close this book/switch off this audiobook, get dressed and go out into nature). For the first half of Star Wars I was overwhelmed and a bit frightened (especially by ‘Dark Vader’), but when Princess Leia referred to Chewbacca as a ‘walking carpet’ everyone in the cinema laughed, including Mum, and I knew I was having the best time of my life.

There was no merchandise in the foyer other than the film soundtrack, which Mum bought on cassette to listen to on the way back to Wales. I thought the ‘soundtrack’ would be all the audio from the film, including the talking and sound effects, and when it became clear it meant just the boring classical music I was gutted. It was the characters I loved, the colourful aliens, the funny robots, the cool Americans; it was them I wished I could take back with me to my room in Wales, even if only in audio form.

Then one day later that year I was in WH Smith’s with Mum and I saw a rack of Star Wars action figures. After some energetic and tearful bargaining, I went home with a little Luke and a tiny R2D2 (those are not euphemisms). From then on I negotiated constantly for action figures, accumulating goodies first and baddies later. It was a shock to discover that ‘Dark Vader’ was actually called ‘Darth’. I didn’t think that was a good space name. He may as well have been called Jatthew, or Vominic. Luckily he had an extendable red plastic lightsaber, though it wasn’t long before I was compelled to bite off the tapered tip.

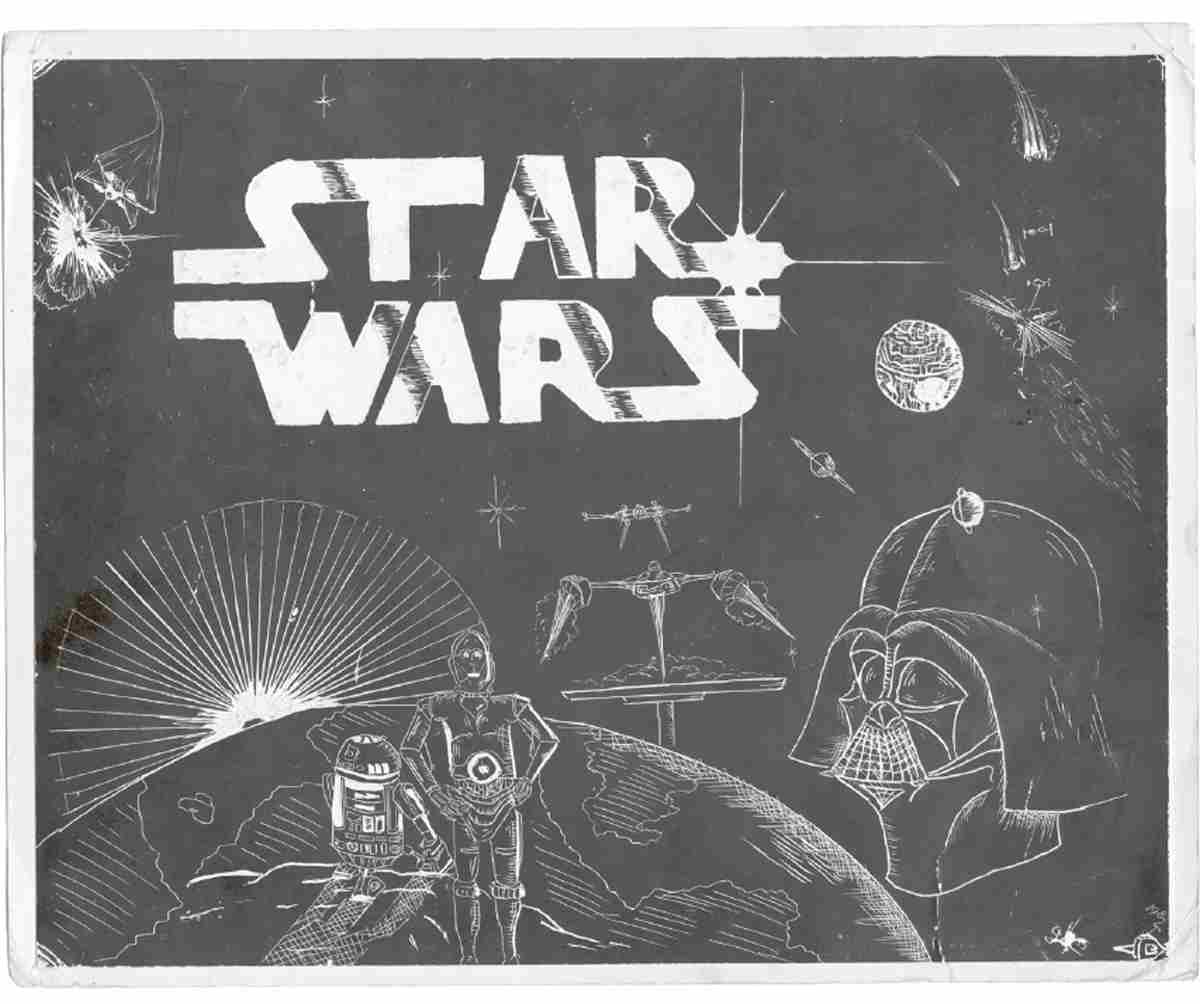

1982 scratchboard art by the 12-year-old, Star Wars-obsessed Buckles. I knew that attempting to draw the humans would go badly, so concentrated instead on the robots, spaceships and a floating baddie helmet.

Over the next three years I wangled action figures of every significant character from the first three Star Wars films, as well as a Landspeeder, X-wing Fighter, TIE Fighter, Droid Factory, Creature Cantina and, on a trip to California when my Aunty Leslie took us to Toys “R” Us and said, incredibly, ‘You can get what you like,’ I came back with a Millennium Falcon. When Dad saw the giant box he made a face that I now understand meant ‘How the fuck am I expected to get that back to the UK, you greedy little shit bag?’ He managed it, though, and unpacking the Falcon on my parents’ bed back in Earl’s Court was no less memorable and moving than the birth of at least two of my children.

As for The Empire Strikes Back, it started out as the greatest film of all time and ended as the most depressing. SPOILER ALERT: Vominic Vader turns out to be Luke’s dad, which we find out after he’s cut off his son’s hand and made him do some very ugly crying. Meanwhile Han, easily the best guy in the whole thing, has been turned into a giant doorstop. For some people this was a more dramatically complex and satisfying ending for a Star Wars film than the cheesy medal ceremony that concluded the first one, but ten-year-old Buckles was not one of those people. If I’d wanted upsetting dramatic complexity, I could have just watched my mum waxing her legs in the nude.

Disney Bangers

Let me paint you a picture of the Britain I grew up in during the 1970s, using all the same bits of archive they use in TV documentaries. There was social and economic upheaval, rubbish piling up on the streets, the dead going unburied, frequent power cuts, racial unrest, football violence, punk music and, worst of all, disrespectful playground poetry. Here is one sickening example:

In 1976

The Queen pulled down her knicks

She licked her bum

And said ‘yum yum’

In 1976

RAMBLE

Although the seven-year-old me admired that poem, and would often recite it, I knew that it lacked plausibility. Was Her Majesty really so flexible that she could lick her own bum? And was QEII so obsessed with rhyming words that she only felt able to pull down her knicks in 1976? Didn’t the underwear come down in 1972, when she must have wanted a poo? None of it adds up.

Whatever grimness was going on in the outside world during the Seventies, my sister, my brother and I knew nothing about it. Mum and Dad subscribed to the Bubble-of-Innocence school of parenting, part of which relied on keeping us gratefully anaesthetised on a Disney drip.

We loved all things Disney: the Land, which we visited several times on trips to America; the TV show (The Wonderful World of Disney); the films and the songs, which we had on four cassettes filled with music performed by fun animals and boring princesses. As the Eighties arrived and my sister began attending the same boarding school, those cassettes were still a crucial part of keeping us pacified on the depressing Sunday-night car journeys back to The Reformatory.

Disney songs reminded me of carefree times when my parents loved me so much they didn’t send me away to expensive prison, but as for the music itself, much of it (to use one of my mother’s favourite expressions) made me want to open a vein.

Our beige Ford Cortina only had a radio, so the Disney tapes would be played on Dad’s portable tape recorder, which sat on the lap of whichever parent (usually Mum) was in the passenger seat. For that reason, it wasn’t an option to fast-forward through the most syrupy, princessy songs. I was only able to endure sludge like ‘Someday My Prince Will Come’ from Snow White, ‘A Dream Is a Wish Your Heart Makes’ from Cinderella and ‘Rumbly in My Tumbly’ from Winnie the Pooh because I knew that eventually we’d get to a Disney Banger.

When songs like ‘Everybody Wants to Be a Cat’, ‘Pink Elephants on Parade’, ‘I Wan’na Be Like You’ or ‘The Bare Necessities’ were about to start, my sister and I would lean forward, unfettered by boring seat belts (which only squares wore in those days), and we’d dig those Disney grooves. I especially liked ‘The Wonderful Thing About Tiggers’ and the hipster beat combo version of Cruella De Ville (different in arrangement and spelling to the version in the 101 Dalmatians film and not, as I search, findable on the Internet).

The best thing about ‘Tiggers’ and ‘De Ville’ was that even Dad liked them and occasionally sang along. ‘Such good lyrics,’ he would say of ‘Cruella de Ville’. ‘Mind you,’ he would continue, ‘I love anything motivated by the patriarchy’s fear of powerful women.’ Alright, those may not have been his exact words, but I think that was the gist.

BOWIE ANNUAL

Exactly 22 years after I first heard his music in an art class, David Bowie walked towards me at Maida Vale studios in West London. It was September 2002 and he’d just performed a concert for BBC Radio, to which Joe and I had been invited by the show’s host, Jonathan Ross. Jonathan knew we were both big fans, albeit fans whose enthusiasm had been tested by Bowie’s musical output for well over a decade. We had learned that when critics greeted each new release as ‘Bowie’s best since Scary Monsters’, what they actually meant was, ‘Well, this one’s not total bollocks.’

And yet, stood in the small audience at Maida Vale watching the 55-year-old Bowie with his boyish floppy hairdo and smart-casual clothes emphasising a face that was at last showing its age, I found myself getting tearful a couple of times, overwhelmed by being just a few metres from someone who had meant so much to me over the years, particularly in the Eighties when I was discovering him and his work for the first time.

Then, after the show, there he was, walking towards a little group of us standing in a backstage corridor with Jonathan Ross. Bowie spotted Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant, who had also been invited along. It was only a year since the first series of The Office had aired, but it had quickly become a mainstream success and Ricky and Stephen were well on the way to becoming full-blown celebrities. I’d met Ricky a couple of times at Jonathan’s house and I knew he was also a huge Bowie fan, so it was cool to see him meet his hero for the first time and have Bowie tell him that he thought The Office was great, but I left Maida Vale deflated.

As well as being an artist whose work I admired, David Bowie was someone I’d always thought of as a person who had a similar outlook on life to me, someone who found the same kinds of things interesting, someone whose taste in music I could trust and whose recommendations were worth exploring. In other words, I’d always thought of him as my friend, but then I had to stand by and watch as he declared his affection, not for me but another comedian. OK, so Ricky was at least as much of a fan as I was, and even back then he’d made a more lasting contribution to the world of comedy, but that didn’t make it any less galling.

‘Serves me right for taking the piss out of Zavid for so long,’ I thought.

After the first flush of unequivocal adoration, Bowie had become something of a comedy character for me, Joe and our friends. We enjoyed dissecting his less well-judged career moments, pronouncements and pontifications, often while doing an impression that relied on the gentle buzzing sound Bowie produced when he spoke words with an ‘s’ in them; for example, ‘zuperlatative’ – a pleasing Bowie variant of ‘superlative’ we’d heard him use in an interview. Over time this impression evolved into a single noise that was our shorthand for Bowie: ‘wuzza’. Instead of discussing the serious issues of the day, we whiled away many hours with symposiums of ‘wuzza, wuzza, wuzza’s. I don’t suppose any of that would have endeared us to Zavid, but I’ve always taken the piss out of people I love, and I really love David Bowie.

‘We’re going to have a free drawing class today,’ said our art teacher, walking over to the record player in the corner and setting the arm down. ‘Here’s some music to inspire you. It just came out last week.’ It was September 1980.

Sun shone through the big glass panels that ran down one side of the art room as the space filled with the sound of clicks, hisses, a rattle, someone counting in, then squalling electric guitar, a woman declaiming in a foreign language and a man who sounded nutty. I exchanged WTF? glances with other mystified ten-year-olds. This music was weird, but the second song was more conventional, and by the time they were chanting ‘Up the hill backwards, / It’ll be all right, ooooh’, I was sufficiently intrigued to ask the teacher who we were listening to.

I liked the name ‘Bowie’. It sounded strong, supple and elegant with the potential to unleash arrows. It was, well, bow-y.

William Mullins (aka Muggins or Bill Muggs) came back to school the following term with his brother’s copy of the Bowie compilation ChangesOneBowie and we listened to it on the common-room record player. Even as I was listening to ‘Space Oddity’ for the first time I was looking forward to hearing it again.

The cover of ChangesOneBowie is a black-and-white photograph of DB taken in 1976 by Tom Kelley, who took the famous nude calendar shots of Marilyn Monroe. It captures Bowie at his most conventionally handsome, yet disarmingly fey. His hair is swept back, his hand is up to his mouth as if he’s considering a work of art, and there’s a distant look in his eyes that says, ‘I’m thinking of complicated things in a more original and zensitive way than an ordinary person would.’ I stared at the cover of ChangesOneBowie and thought, ‘Mmm. Yes, please.’

A few weeks later Bill Muggs turned up with Hunky Dory and, though I was a bit confused by Bowie suddenly looking like somebody’s hippy mum on the cover, as soon as ‘Life on Mars’ came on with lyrics about cavemen and Mickey Mouse combining the esoteric and the accessible, I recognised it as the kind of powerfully dramatic, emotional and mysterious music I’d often heard playing in my head, playing in my heart even, but never out loud. Or maybe I’d just heard it on the radio and forgot.

Either way, I realised I was interested in David Bowie.

Up to that point all the strangers I’d been interested in were fictional – the Bionic Man, the Bionic Woman, the Invisible Man and the Man from Atlantis – not really superheroes, but enhanced humans that I thought I’d get on well with. Bowie was the first real person to join that list, and for the next few years we got on very well indeed.