Chris’ road trip starts in Yugoslavia during World War II.

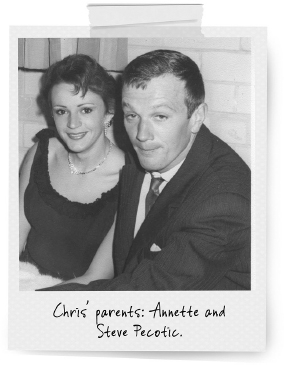

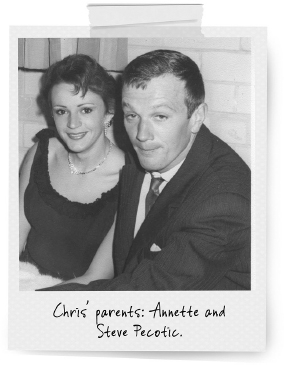

My father, Steve Pecotic, was one year old when he lost his father – a victim of war in Croatia.

My father had nothing to remember about his father. He and his two siblings were brought up in hardship in a small peasant village by their mother.

She had witnessed the murder. It had a profound impact on her. She was later to suffer severe forms of schizophrenia where she not only heard voices, but saw images.

When I have been psychotic from trauma and ice, I too have seen things so this is very haunting and vivid to me. My father’s sister was also diagnosed with similar strains of madness. Is this hereditary? Have I now passed this condition onto my daughter?

When we were living in St Albans in Melbourne my mother and father separated due to domestic violence. I was about four years old and my brother, Barry, about two. I don’t recall ever seeing my dad hit my mother, but I was exposed to a lot of yelling-abuse by my dad.

My mother left my dad, taking us with her, and was living in a bungalow at the rear of a house.

I was my dad’s boy and loved being with him, even though he was very hard on us. My brother was Mum’s boy, but I would look forward to seeing my dad on his access weekends.

He raised me on stories of his exploits as a wayward kid. These were his family stories for me.

From his poor village in Croatia, he’d terrorise the locals with a sawn-off shotgun. He was a kind of bandit and then fled to Australia.

I found his tales to be funny. Criminality was nothing to be frowned upon.

And so I never really gave crime a second thought.

I entered the life with petty thefts of chewing gum from gum racks at supermarkets.

I’d seek out the closed checkouts, empty the gum-racks into a plastic bag, and then exit the store.

My first aspirations towards armed robbery formed when I did banking for my sick grandmother.

The bank was on a corner; sometimes I would see the guards arrive delivering the cash. I studied their routines.

As an 8- or 9-year-old, I’d cock my right hand and tell them to give me the money.

From that time on I dreamt of robbing them.

My mother formed a relationship with a man who became my stepfather. His name was Hans Binse.

But I did not enjoy the presence of my stepfather – it was like my attachment to my dad was supposed to be severed and replaced with a substitute. He tried his best but he could not be my dad ever.

And later they got divorced, too.

My dad at an early age encouraged me into petty theft from work sites. He was a subcontractor carpenter, and would have me keep cocky when he ventured into the garages of those jobs he was at, and lift items.

I wanted my dad to look after me, and when I was allowed to choose who to live with I chose my dad. I wanted to be at home with him, but he got too angry, too violent. His temper was too brutal. Living with him full time was not possible. I couldn’t stay for long.

When I returned to my mother’s from the weekend visits, I would rebel. I was a delinquent and would run away from home, because I felt I did not fit in at Mum’s place either. I would break into cars to sleep in and steal coins from them to buy food to survive, coming to the attention of police who arrested me and returned me to my mother who would complain I was bringing the police to her place and she would talk about what her neighbours would think.

I’d get arrested and returned to my mother’s home and then I’d run away again.

My mum could not control me. I was constantly rebellious, and as a result I was abandoned by my mother who took me to court to have me deemed uncontrollable and made a ward of the state.

The courts had sought that I be assessed by psychiatrists, but this was a six to eight week wait, and by the time my file arrived on the desk I had run away again.

Now I was made a ward of the state, and nobody really ever got to find out why I was running away.

At thirteen years of age I got locked up in Baltara, the under-fourteen section of Turana.

At this tender age I was subjected to bashings by staff in the Warrawong punishment block. They told us kids that the bashings were to deter us from coming back to that section.

Yet when I was near release, I would inexplicably run away.

I had a fear of going home, I now feel, because I didn’t want to be there at all.

So began my life of crime at thirteen. Bullying was very prevalent at Baltara, and if I wasn’t facing that I was spending long periods alone in a cell. No TV or anything.

To this day I refuse to forgive my mother for this abandonment of me, and for all the violence I was subjected to as a minor.

I hated being in custody. It destroyed my spirit. It crushed me.

And from that moment on, figures of authority – the custodial staff – bashed us, bashed me, and so formed the enmity towards the government and guards that would shape my life for so long.

Over the years ahead I would be bashed many times by police, sometimes savagely when they wanted to know where the cash was. Other times they did it thinking they could belt me into giving up others – yet torture made me even stauncher – or because they wanted to teach me who’s boss. Or because I was a cheeky cunt.

Released from Baltara boys’ home during the day to go to school, I began using drugs, stealing, and returning to custody.

My life of crime had begun in earnest. Listening to older kids talk about their escapes and exploits appealed to me.

I become a pot smoker at fourteen, and then experimented with all types of drugs including speed and even heroin.

I rebelled. I competed with fate. And when I was in that mindset, I escaped at the first opportunity.

This caused me to accumulate a three-year term as a juvenile: the maximum a kid could get in children’s courts at the time.

Due to my frequent escapes, I was housed in the most secure location they had: Poplar House at Turana. A mini-jail for kids: a high-walled fortress with many rolls of barbed wire.

I escaped from this location just to prove I could crack it. And got taken back. And escaped again. And got taken back again.

Bored and restless, I spent a few years there.

When I escaped, it started to become out of sheer boredom with the place – not due to want of liberty. What liberty is there outside as a kid with no family, no home, a mother who went to court to get rid of him?

I was transferred to Malmsbury youth training centre at seventeen, and then, after the death of my beloved grandmother in 1986, I escaped and went on a drug-fuelled crime spree for four weeks until being arrested and sent to Pentridge, a maximum-security adult prison where ugliness and violence were the air and water.

I was seventeen years old.