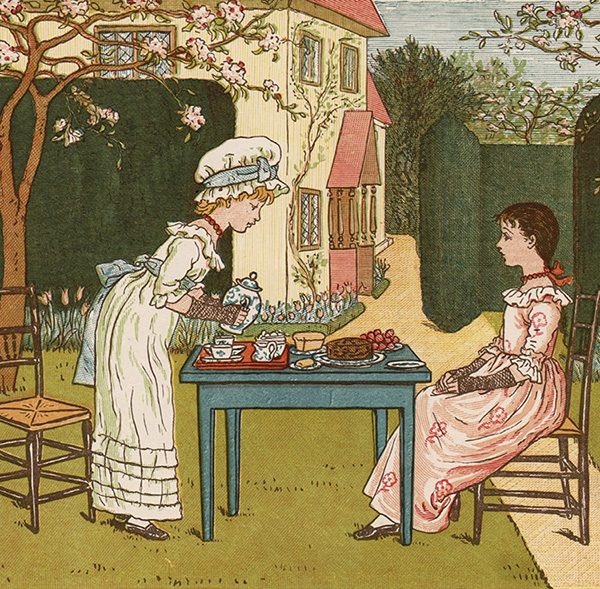

Kate Greenaway, illustration from Under the Window: Pictures and Rhymes for Children, 1878

IN THE 1870S, ENGLAND BEGAN TO EMERGE from the heavy shroud of Victorian design sensibilities by embracing a new aesthetic that would have ramifications on the design of houses, interiors, and decorative arts until the First World War. The Aesthetic Movement, which centered on the world of James McNeill Whistler and Oscar Wilde, ushered in a new concept in domestic architecture and interior design known as the “The House Beautiful.”1 The concept of artistic houses characterized by the lightness of their interiors and decorated with beautiful objects was a welcome relief from the heavy furnishings, dark interiors, and somber palette of the Victorian era. This new aesthetic was especially appealing to the growing middle classes with newfound artistic yearnings.

The parallel Queen Anne Movement, with its distinctive style of architecture that harked back to an earlier period in English history, took hold in London’s newly fashionable enclaves, such as Chelsea and Bedford Park. The leading architect was Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912), who, along with Ernest J. May, designed the artists’ suburb in Bedford Park. There, red-brick houses featured picturesque turrets and gables, with artistic interiors in soft, pleasing colors. The Queen Anne style was personified in nursery books written and illustrated by Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, and, above all, Kate Greenaway, whose books Under the Window (1878), Mother Goose (1881), A Day in a Child’s Life (1881), and Marigold Garden (1885) depict caricatures of Shaw houses. Her own brick house in Hampstead was designed by Shaw in 1885. In her books, children decked out in sunbonnets play outdoors amid green croquet lawns and gardens filled with colorful flower borders and enormous topiary shrubs and trees. The steep, red-tile roofs of houses peek over the tops of high green hedges and garden walls. Young ladies enjoy a leisurely afternoon tea on the lawn, with flower borders bursting with sunflowers and roses and the Shaw-inspired house on the other side of the wall.

The Queen Anne style, for all its quaintness, was more suited to townhouses, shops, and suburban neighborhoods than to country houses, for which something more traditionally English was called for.2 It was during this period that former country seats were replaced by smaller houses inspired by old English models of many forms. According to Ernest Newton (1856–1922), one of Shaw’s pupils, these pioneer architects “aimed at catching the spirit of the old building rather than at the literal reproduction of any defined style.”3 Newton’s genteel houses, such as Fouracre, in Winchfield, Hampshire, of 1901, definitely catch this spirit. The red-brick house, with decorative bands of trim and the front door opening out onto the garden, is simple, genial, and welcoming. As with many of the architects of the era, Newton’s career advanced from Queen Anne and Tudor to Georgian revivals.

Ernest Newton, House Near Winchfield [Fouracre], watercolor by T. Hamilton Crawford, 1902 (Sparrow, 1906)

Shaw was a versatile architect best known for his old English style. His country houses, such as Cragside in Northumberland, are generously sized and include half-timbering and other traditional details. Perched on a steep ledge, Cragside is surrounded by acres of naturalistic woodland gardens (primarily rhododendrons, heathers, and alpines) and numerous water features. In addition to Shaw, the leading practitioners of the new architecture were George Devey and Philip Webb. Devey (1820–86), a superb watercolor artist known for his picturesque approach to design, was one of the first Victorian architects to create houses based on the local vernacular, an important issue for Arts and Crafts architects.4 Devey’s sympathetic restorations of older buildings were drawn from an extensive knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean architecture.

Philip Speakman Webb (1831–1915) undoubtedly had the most far-reaching influence of the trio. His houses evoke the old in detailing but are innovative in planning, reflecting his passion for traditional building and local materials without copying them in a historicist fashion. A master of understatement, Webb profoundly influenced the coming generation of architects. Standen, which he designed in 1891 for London solicitor James Beale, is his masterpiece. The brick-and-stone house, with its distinctive wooden gables and tile-hung façade, takes its cue from the old farm buildings on the site that other architects might have torn down. Webb’s unusual sensitivity to vernacular buildings and details had an enormous influence on the design of country houses in England.

In 1886, at Great Tangley Manor, near Guildford, Surrey, Webb redesigned and extended a half-timbered house with origins in the sixteenth century. He returned in 1894 to add a stone library wing that complemented the old half-timbered front. Webb’s garden architecture included a timber-roofed bridge over the moat and a rustic pergola. These improvements drew considerable comment from Gertrude Jekyll, who lived nearby and had known the house in its former, more dilapidated and overgrown state. The ancient enclosure, with its arched doorway and loopholed walls, inspired Edwin Lutyens at Millmead and elsewhere.5 The flower borders within the enclosure, which were characteristic of the era, were filled with a pleasing mixture of lilies, irises, and larkspur.

Small country houses within easy reach of London for weekend retreats for the upper middle class would become the realm of a new generation of architects, mostly born in the 1860s, who trained in some of the most prestigious offices of the day. In addition to Newton and May, Shaw’s office produced William R. Lethaby (a major theorist of the era), Gerald Horsley, Mervyn Macartney (the influential editor of The Architectural Review), Edward S. Prior, and Robert Weir Schultz. Ernest George’s office trained Herbert Baker, Guy Dawber, and Edwin Lutyens, while John Sedding’s office trained both Ernest Barnsley and Ernest Gimson.6 Beginning in the 1890s, these architects and a host of others would create some of the signature examples of domestic architecture associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, bringing England to the forefront of architectural design.

Unquestionably, the stars were Lutyens, whose romantic Surrey houses built from local stone gave new definition to the concept of vernacular; Voysey, whose quirky, whitewashed, roughcast houses and austere furnishings were universally hailed; and Baillie Scott, whose half-timbered suburban cottages had a profound impact on domestic architecture. Despite the various sources of design inspiration, whether Gothic Revival, Byzantine Revival, classicism, or vernacular, these architects were united by their staunch individualism, regionalism, and respect for traditional building arts.

In the early 1900s it took an enlightened foreigner to appreciate the importance of architectural developments in England. Hermann Muthesius (1861–1927), the court-appointed attaché to the German Embassy in London, extolled the new “free” style in his three-volume work, Das Englische Haus, the result of his detailed study of English domestic architecture. While living in Hammersmith, Muthesius fell in with the Morris circle and came to admire the recent work of Shaw, Lethaby, Voysey, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Muthesius credited the phenomenon of the English country house to the Englishman’s desire for “sincerity and unpretentiousness” in his house, as well as the avoidance of any kind of display, rather than deliberately aiming at a specifically modern look. “The fundamental traits of the English house are its reserve, modesty, and charming sincerity.”7 He singled out Jekyll’s Munstead Wood as a worthy contrast to the English house of fifty years earlier, a period he considered a low point in domestic architecture.

Sparked by John Ruskin, William Morris, and their followers, who called for design reform based on simplicity and utility, the new movement championed the England of happier, preindustrial days. Picture books and paintings of the latter part of the nineteenth century portrayed a romanticized rural England, its landscapes, vernacular architecture, traditional crafts, and leisurely pursuits. The artist Helen Allingham’s book Happy England (1903) paints an evocative picture of the English countryside filled with quaint cottages, lush flower borders, and beautiful children. Allingham’s nostalgic view of country life is one seemingly devoid of hardships and the negative effects of industrialization.8 Legions of artists, poets, and writers extolled the virtues of country living as opposed to the grim realities of city life. The back-to-the-land movement was sparked by a newfound reverence for the unspoiled English countryside and its rural traditions as an escape from the unhealthful atmosphere of cities, as well as their inherent social strictures. Ruskin’s plea for recognition of artists and artisans alike was only one manifestation of the underlying social dissatisfaction of the day.

The Arts and Crafts Movement emerged from deep moral and social concerns. The complexity of the movement’s origins, ideals, and manifestations has been the subject of many detailed studies, but its basic tenets were a fundamental disdain for the falseness of High Victorian design, a rediscovery of nature and English traditions, and the idea that manual work could be personally fulfilling.9 Inspired by Morris, those who embraced the movement sought to bring together architects and craftsmen to work in harmony. In 1884, a group of Shaw’s assistants founded the Art Workers’ Guild to provide a meeting place for architects and craftsmen to discuss their work, which quickly fused together some of the movement’s early objectives.10 One of the guild’s early ventures was the establishment of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, which eventually provided a name to the new movement. Beginning with its first exhibition of members’ work in 1888, it served to spread the word about design reform. Founded in 1893, The Studio magazine published illustrations of their architectural perspectives, garden designs, metalwork and jewelry, ceramics, textiles, and wallpapers, all of which rubbed shoulders happily with one another.

The Arts and Crafts Movement championed the unity of the arts, in which the house, the furnishing of its interiors, and the surrounding garden were considered a whole, or as Muthesius expressed it, “garden, house, and interior—a unity.”11 The parallel revival of the art of garden design came into play at a time when architects not only saw to every detail of the house and its interiors, but routinely laid out the gardens. These gardens, with their neatly clipped hedges and ordered geometry, harked back to the England of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the pleasure grounds of the Tudors and Stuarts. In contrast to nineteenth-century estate gardens that were vast in scale and stiffly planted with brightly colored annuals and jarring foliage, gardens designed by Arts and Crafts architects and their collaborators were intimate in scale, with soothing colors and textures. They harmonized perfectly with the house and were often distinguished by individualistic architectural components, such as garden houses, dovecotes, and pergolas, all constructed using the local materials of the region.