5

The second thing Corey noticed, as he burst out of the building and onto Central Park West, was that the old man was gone.

The first thing was piles of horse manure on both sides of the road. He looked up and down the street, his chest heaving. Papou was nowhere in sight. The Walk sign was gone, too, as well as all streetlights and cars. The blacktop road was hard-packed gravel, and the silence was overwhelming.

He turned back to Leila’s building. It was always the runt of the block, wedged between high-rises. Leila called it “the Little House” after her favorite picture book. Now it was the tallest building in sight. The great Central Park West towers were gone. All the way up into Harlem, and down to Columbus Circle, was a hodgepodge of low-rise brick buildings, shacks, and empty space.

“I need a shrink . . . ,” Corey murmured. “I need a shrink. . . .”

There was a name for this condition, having delusions and believing them to be true. But he’d forgotten it. People like him ended up ranting in the streets to imaginary enemies. They sat muttering in the subways.

He never thought his senses could lie to him, but they could and they had. He smelled the manure that the horses had left in the street and the burning of wood in fireplaces. He saw sky in places he’d never seen it and heard the quiet of a city without machines. It all seemed so real.

Corey felt woozy. His stomach churned, like he’d been in the car too long. He staggered across the street. Behind him he heard the crack of a whip and a horse’s whinny. “Get out of the way, ya drunken rascal!” a gravelly voice shouted.

He jumped onto the sidewalk, narrowly avoiding a horse-drawn coach.

“You’re not real!” he shouted.

Tripping over the uneven pavement, Corey fell against the park’s stone wall. He glanced up as a windowed coach made of dark polished wood rolled by. A white-gloved hand pushed aside the window curtains, and a wrinkle-faced man in a top hat glowered at him.

“You’re not real either,” Corey muttered.

“Hmmf,” the old man sniffed.

From Corey’s left, a softer voice called out, “You okay, fella?”

Corey looked. A guy in a loose gray workman’s uniform was on his knees, holding on to a stone with a gloved hand, about ten feet farther down the wall.

The stonemason.

“You—you were in the photo!” Corey blurted, hopping to his feet. “From the eighteen hundreds!”

With a snort, the guy turned around to another worker and made a circle sign with his index finger on the side of his head. Cuckoo.

Corey slumped on a park bench. It hadn’t yet been bolted to the sidewalk, so he and the bench teetered backward. Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed a white envelope slipping off the seat and falling to the ground.

He lifted it and looked at the writing:

For Buster Squires

His hand began to shiver. Then his whole body. It was Papou’s nickname for him.

Steady, Corey, he thought. Go with it. It will all fade away and you’ll snap out of this.

Whatever this is.

“Son? You lost or something?”

Corey barely registered the stonemason’s voice. He ripped the top off the envelope and pulled out a message.

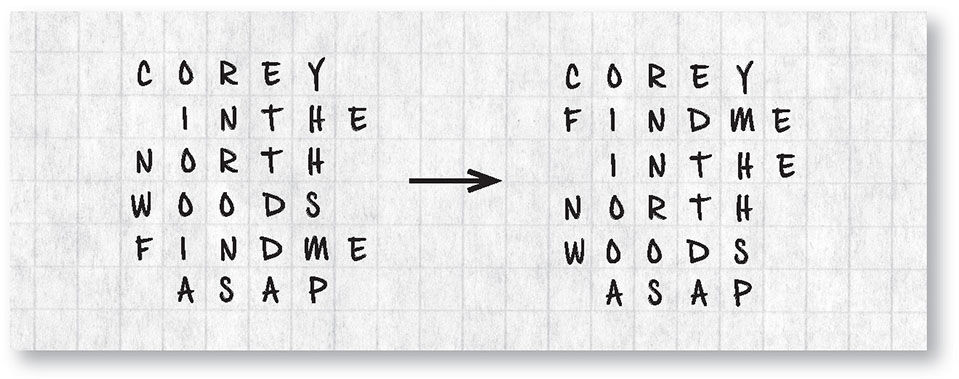

Graph paper. Just like Papou used all the time. Their house was full of graph paper. All his life Papou had been an engineer. He’d buy pads and pads of it.

“I’m not seeing this . . . ,” Corey said.

The stonemason was standing next to him now, looking warily over his shoulder. “Looks important. You got a marriage proposal in the mail?”

“My grandfather,” Corey replied.

“A marriage proposal from your grandfather?”

“No!”

Don’t talk, Corey said to himself. He is not real. This is your imagination.

Corey envisioned himself as the real world must be seeing him—sitting on a park bench, talking to no one. He watched suspiciously as the man leaned to look at the note. “You are a delusion,” Corey said. “A figment.”

“Nope, an Italian. Lorenzo Scotto.” He stuck out his hand and Corey shook it. It felt real, all right. Like a slab of granite. “Looks like you got some kind of riddle there, kid. Your grandpa likes riddles?”

Corey closed his eyes for a few seconds, thinking this all might disappear. No such luck. Lorenzo stayed put.

“He likes codes,” Corey murmured. “Puzzles. He taught me to do the New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle.”

“I don’t read the Times. Maybe I should. I’m a Frank Leslie kind of guy.” Lorenzo reached into his back pocket and pulled out a tabloid newspaper, slapping it down on the bench next to the discarded envelope. “Good to meet you . . . Buster.”

The masthead of Lorenzo’s newspaper said Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The front page was full of garish hand-drawn scenes—stabbings, fat men in top hats, monster-like people attacking helpless rich folk.

But Corey barely noticed those.

He stared at the date on the top of the front page:

October 31, 1862

A breeze wafted by his face, carrying scents of dirt, manure, rotting leaves—and newspaper print. Corey felt numb. “Tell me this isn’t real.”

Lorenzo laughed. “Well, you know Frank’s, they can flower up a story.”

“No, I mean all of it. I mean the date,” Corey said. “Is it really October thirty-first, 1862?”

“That’s what I say, too. Hoo-eee, October already! Seems like it was summer just yesterday!”

“That’s not what I meant.” Corey sank back into the bench again. He looked Lorenzo straight in the eye. “It is 1862. It really is. I’m not crazy. There are no cars, right? Or telephones. There’s a war down South. And my grandfather is here all alone, trying to tell me something! Is this all true?”

Lorenzo shrugged. “Well, you’re making sense to me. Can I ask you a question? I know times is tough. Your grandpa, ain’t he got a place to live?”

“Well . . . I don’t know. He left home and never contacted anyone. So maybe yes. Maybe no.”

“That’s why he’s using code, then. Doesn’t want nobody to find him but you. Prob’ly got his reasons. Nowadays you never know why people do the things they do. Anyway, them constables, they’re liable to throw him in jail for vagrancy.” The man smiled. “Hey, I’ll help you if you want. I may be Italian, but I’m good at puzzles.”

Corey cocked his head curiously. “What does being Italian have to do with that?”

Lorenzo shrugged. “Ahh, you know, the hoity-toity, they all think we’re a bunch of monkeys with no brains. They want to build a park on this land, right? Bang, they kick us out of our houses—us, the Poles, the Africans, the Irish. Businesses, churches, gone. Now all the swells can have a place to show off their carriages. And whaddaya know, all the land around the park gets expensive, too! Right where they’re buying up land. What a surprise!”

“It will get worse,” Corey murmured. “Apartments for a hundred million dollars.”

“Lucky us, we get to build this stone wall around the park,” Lorenzo barreled on. “And then we go home to little shacks where they can’t see us. Someday this will change. Now show me that puzzle before I get too angry to think.”

Corey held out the sheet to the man.

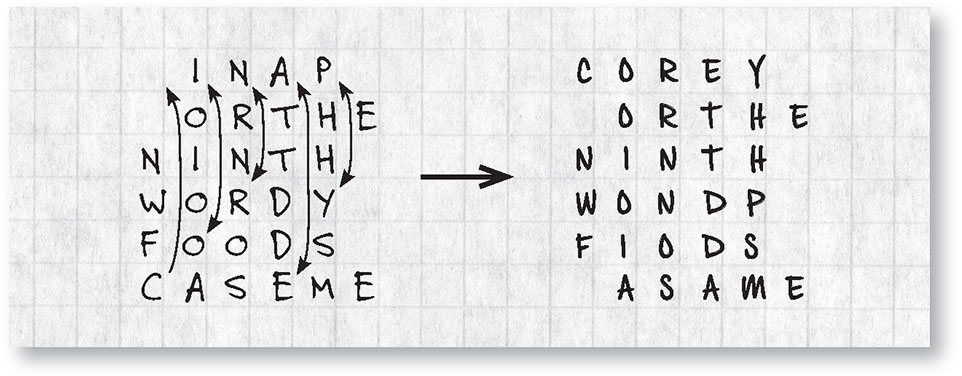

“‘Dumbwaiter delivers one to twenty-six,’” Lorenzo read aloud. “Okay, I’m going to put some spaces in the next words, or it don’t make no sense. ‘I nap, or the ninth wordy foods case me.’ See, I read pretty good!”

“But that doesn’t make sense,” Corey pointed out.

“Yeah, good pernt,” Lorenzo agreed.

“Pernt?” Corey said. “You mean point?”

“’Swhat I said. Pernt. Okay, let’s start with the dumbwaiter and work our way down.” Lorenzo widened his eyes like a bad standup comic holding for a laugh. “Ha! See what I did there?”

“Right . . . dumbwaiter . . . work our way down . . .” Corey forced himself to concentrate. “But doesn’t a dumbwaiter carry things up and down—like an elevator?”

“An ele-what?” Lorenzo asked.

“Right, maybe they haven’t been invented yet,” Corey said. “So, yeah. Dumbwaiter. And the one to twenty-six, that could be floors of a building.”

Lorenzo laughed. “That’d be some building! The walls would have to be a mile thick to hold the weight. You know what I think? We gotta look at the top part of this code first. It’s some kind of way to understand the bottom. A kind of . . . whaddaya call it—?”

“Key!” Corey replied.

“Key.”

“Uh-huh,” Corey said. “So the top part of the message is telling us to decode the bottom by carrying something up and down. . . .”

“Like a dumbwaiter . . . ,” Lorenzo murmured. “But why ‘one to twenty-six’?”

Corey thought a moment. “It’s twice thirteen. Twice the bad luck.”

“There’s also twenty-six letters in the alphabet.” Lorenzo pointed to his head. “I remember that from school.”

“Yes! What if ‘one to twenty-six’ is a way of saying the letters go up and down?” With Lorenzo looking over his shoulder, Corey focused on the bottom part of the message. “So if we read these letters vertically in each column . . .”

He silently read the columns of letters, top to bottom: NWFC IOIOOA NRNROS ATTDDE PHHYSM E E.

“I don’t think so,” Lorenzo said. “Unless that’s Greek or something.”

Bottom-to-top was nonsense, too.

“Okay, okay, we can get this . . . ,” Corey said. “Could be it’s not about reading up and down. A dumbwaiter . . . moves stuff.”

“We knew that.”

“From floor to floor.”

“We knew that, too.”

“Maybe that’s what we’re supposed to do, Lorenzo—move the letters. Like a word scramble, but vertical instead of horizontal.”

Lorenzo scratched his head. “That first column is N, W, F, C. No matter how you scramble that, it ain’t nothing. No vowels.”

“Yeah, but what about rearranging vertically, and then reading what you get horizontally?” Corey said.

“This is getting complicated,” Lorenzo said.

“Papou always told me, when you think it’s impossible, ‘Look for something you recognize.’ . . .”

Lorenzo scratched his chin. “Well, this is a note to you, right? Maybe your name is in it. Like, hidden.”

Corey stared at the graph paper. C in Column 1, O in Column 2, R in Column 3 . . . “I think I see it.”

Lorenzo pulled a pencil from behind his ear. “Need this?”

The pencil was greasy and chewed up, but Corey didn’t care. Taking it from Lorenzo, he began rearranging:

“I thought your name was Buster,” Lorenzo said.

“It’s a nickname. Corey’s my real name.”

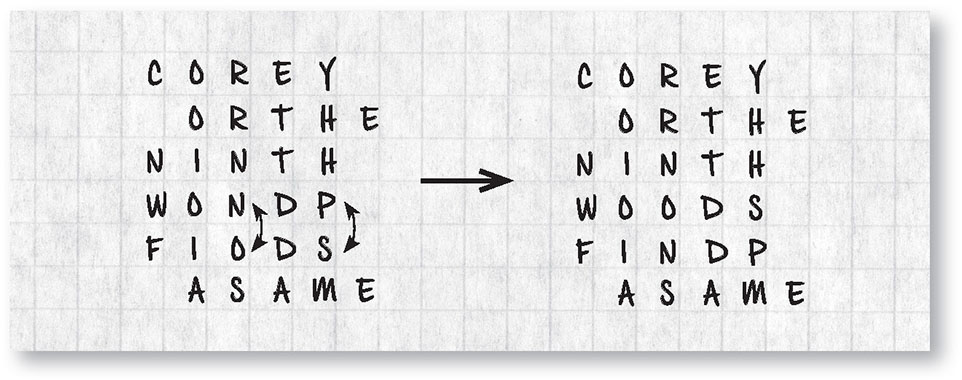

“Well, razzamatazza! Hey, now I’m seeing another word—woods!”

Corey saw it, too:

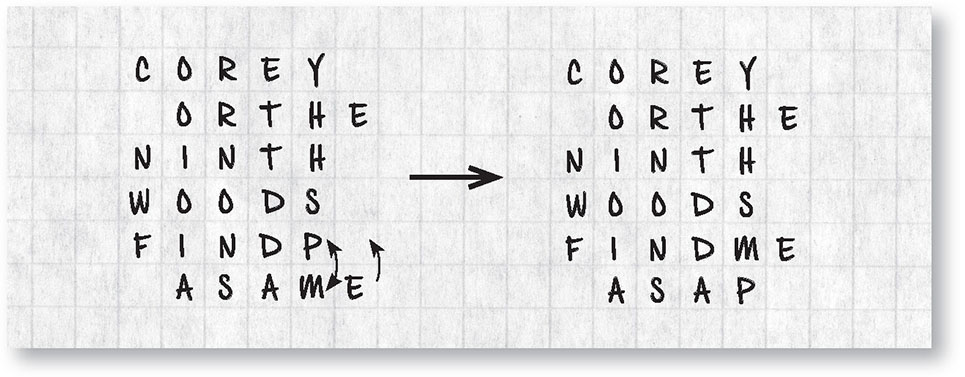

Corey’s eyes widened as he stared at the bottom two lines.

“I see find,” he said. “And I see me. ‘Find me’!”

“Like I said, the guy is scared,” Lorenzo whispered. “He don’t want no one to see you meeting him in public.”

FIND ME ASAP.

That did not sound good. Sweat gathered on Corey’s scalp as he began fixing the rest of it.

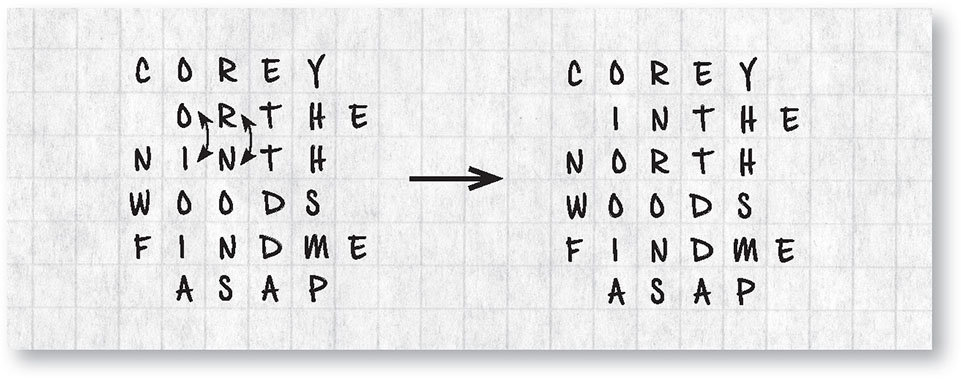

Finally he made one small rearrangement to get the message.

“He needs me!” Corey blurted out, his chest thumping.

“Smart guy,” Lorenzo said. “If somebody besides you picked this up, they wouldn’t know where he was. I’m reading it, and I don’t know. Where’s the North Woods?”

“Nowhere now. It’s where it will be,” Corey said. “The top of the park—like, a hundredth to a hundredth and tenth streets. They left it—I mean, the park designers are planning to leave it like a forest.”

He bolted up from the bench and stuffed the note in his pocket, quickly shaking Lorenzo’s hand. “Thanks for your help.”

Lorenzo smiled but didn’t let go. “Wait. Maybe you can help me now. Just one question. Who the heck are you, and how do you know so much about things that haven’t been invented and what’s going to happen with the park? I may not be too smart, but I want the truth. And don’t worry. I keep secrets.”

Corey locked eyes with the man. He believed that Lorenzo kept secrets. He also believed the man was very smart. And Lorenzo deserved the truth, as crazy as it should sound.

“I—I’m from the future,” he said. “I traveled in time.”

Lorenzo’s bushy eyebrows collided at the top of his nose. “Yeah? How?”

“I’m not sure. It has something to do with a locket and a belt buckle, I think.” Corey took a deep breath. “You think I’m nuts, right?”

Lorenzo shook his head. “I read Frank Leslie every week. There’s all kind of weird stuff goes on in this world.”

“So you actually believe me?” Corey asked.

Behind Lorenzo, another workman was clearing his throat. “Hey, hate to break up the party, your highness, but there’s woik to do,” he grumbled.

“Shut yer trap, be right there,” Lorenzo replied.

He gave Corey a long, hard look. “I don’t know if I believe you. You’re dressed like nobody I ever seen, you use woids I never hoid of before, so I don’t know what to make of you. But I told you I kept secrets, and I’m a man of my woid.”

Corey edged backward. “Well, I appreciate it. So—”

“Just a sec.” Lorenzo stepped up close to Corey. “What if you are telling the truth? Just for grins, can I ask you another question? Just between you and me?”

“Sure,” Corey said. “Whatever.”

“I don’t believe I’m asking this.” Lorenzo took a deep breath. He shook his head and muttered something in Italian that sounded like a prayer. “Tell me, Future Boy, does the country survive the War Between the States?”

“It will be called the Civil War,” Corey replied. “And, yes.”

“No joke?” Lorenzo’s left eyebrow arched skeptically.

“Abraham Lincoln signs an emancipation proclamation, the slaves are freed, and the South joins the North as one country. It gets really complicated after that, but . . . yeah.”

The man’s eyes grew moist. “Bless you, big guy,” he said. “Your grandfather is a lucky man.”