Timothy Stapleton

Heidegger uses the word “Dasein” to refer to what customarily might be called the self or “I”; or, as he more cautiously puts it, to “this entity which each of us is himself” (BT 27). But while the denotations of the words “self” and “Dasein” may be the same, the connotations differ radically. When properly understood, “Dasein” captures the unique being of the “I am”, one that gets misconstrued by such terms, for example, as “self”, “ego”, “soul”, “subjectivity” or “person”. For Heidegger, what constitutes the very “am” of the “I am” is that being is an issue for it: is a question and a matter about which it cares. This entity that I am understands this implicitly. More radically, it is this understanding, or the place where this understanding of being occurs. Hence “Dasein” means the self as the there (Da) of being (Sein), the place where an understanding of being erupts into being.

“Being-in-the-world” is Heidegger’s descriptive interpretation of the self as Dasein. For Heidegger, as we shall come to see, description and interpretation need not be at odds. One sort of interpretation (Auslegung), as a laying-out of that which is only tacit, is description. “Being-in-the-world” is intended to capture descriptively various dimensions of what it means for Dasein “to be”. But much more needs to be said, in the way of interpretation, about this description.

Being and Time is a work in ontology. It enquires about the meaning of being. Being is always the being (Sein) of some entity or being (Seiendes); of trees and tables, of human beings and their questions. “Ontic” is the expression Heidegger uses for beings and our way of talking about them, “ontological” for the being of such beings and its language. The ontic and ontological are inseparable. But ontology must always begin with the ontic and move towards the ontological. Moreover, “Dasein is ontically distinctive in that it is ontological” (BT 32). Being ontological here points to that implicit understanding of being that occurs with and in Dasein’s existence. But what, more concretely, is this implicit understanding of being?

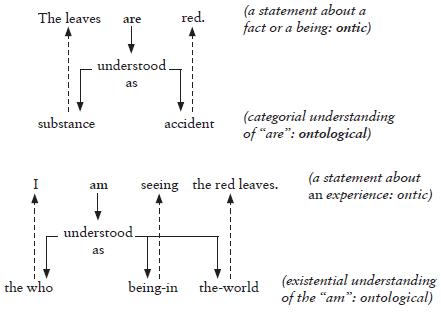

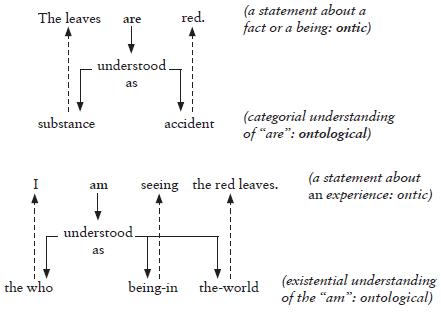

Let us begin with a simple example. I gaze out of the window and see, against the background of the Masonic Temple’s rigid, grey brickwork, the red leaves on the branch of a maple stir in the late afternoon breeze. What I see is a tree, its branches and red leaves. What I apprehend, more precisely, are not just the leaves and the colour red, but the leaves being red. I do not say, for instance, “leaves red” or “leaves and red”, but, rather, “The leaves are red”, “The clouds are gathering”, “A man dressed in a plaid kilt is walking past”. For Heidegger, there is an understanding of being as substance (the being of the leaves) and accident (the being of the redness) that accompanies such simple experiences; that guides and structures them in advance (a priori) and makes it possible for what I experience to be what it is. Being as understood in terms of these traditional categories is what Heidegger calls “categorial”.1

One of the first ways Heidegger talks about being is as “what determines entities as entities” (BT 25). Being does not “make” beings be in the sense of create or cause them. “To determine” here means something more like opening up a place or space where these entities can show themselves for what they are. Or, as Heidegger sometimes says, being frees beings for their being.

Furthermore, this understanding of being is itself something. The understanding of being understands its own being as well. While gazing across the garden at the red leaves of the maple, I am at the same time aware that I am seeing this. This self-awareness is not something that emerges only when an explicit act of reflection takes place. A pre-thematic self-consciousness is an essential dimension of lived awareness. The crucial question is: what sort of understanding of being accompanies or “determines” this lived self-awareness as the sort of thing that it is? Heidegger claims that all too often the understanding of being that frees objects within the world for their being gets reflected back on the being of the experiencing itself. The “I” gets taken as a substance, although perhaps of some special sort (ego, mind, res cogitans, soul), and the “seeing” as an activity of this I-thing.

Ontologically, every idea of a “subject” – unless refined by a previous ontological determination of its basic character – still posits the subjectum (hupokeimenon) along with it, no matter how vigorous one’s ontical protestations against the “soul substance” or “reification of consciousness”.

(BT 72)

Even when subjectivity is understood not as isolated from, but rather as connected essentially and “intentionally” to, the objects of its experience (the position Heidegger associates with traditional phenomenology at that time), nothing changes with respect to the ontology at work. The self or the subject and its acts of awareness are still taken as entities that present themselves to the thematic gaze of reflection, as already there and given so as to be apprehended in such reflection.

Two closely related points should be noted here. First, Heidegger wants to claim that the traditional understanding of being, guided by the notion of substance, is inseparable from the idea of “presence”. That which really is, the ontōs on, is that which presents itself, and the pre-eminent temporal mode of presentation in which this takes place is in the present. Secondly, there is an intimate connection between this understanding of being and the theoretical attitude itself. When a theoretical orientation is assumed, one stands back and looks, inspects, gets a critical (objective) distance so as to see how things “really are”. Whether empiricist (sight and the senses) or rationalist (the eye of the mind, insight, the eidos or Idea as that which is illuminated), to be is to be “seeable”. Among the guiding ideas in the Western tradition is that the movement from seeming to being, from appearance to reality, requires the assumption of the theoretical attitude. But this move entails positing that understanding of being which is necessary for theory itself.

Heidegger’s new, fundamental ontology must combat the considerable weight of both of these prejudices – grounded as they are in language, tradition and a tendency towards such self-concealment that is part of Dasein’s own being. The hegemony of the categorial is to be challenged, and Heidegger does so by trying to understand and interpret Dasein’s “to be” as being-in-the-world.

When Heidegger first introduces the expression “being-in-the-world”, he calls attention to several important features. First, although a compound expression, it nonetheless signifies a unitary phenomenon. This unity is an essential one: its different dimensions not so much pieces (like the legs and top of a table) but moments (like the colour and shape of the table top). The hyphenated nature of the expression does nothing but emphasize this elemental unity. Furthermore, Heidegger notes that being-in-the-world is triadic. There is (i) the “in-the-world”, (ii) the “being-in”, and (iii) the entity or “who” which is as being-in-the-world. Each of these dimensions will be laid out in turn, but with a constant eye kept on their essential interconnectedness.

These analyses (constituting a Dasein analytic) must be understood as an attempt at a “non-categorial” ontology. Heidegger uses the word “ Existenz” to refer to the unique kind of being that Dasein “is”. Rather than categories, the basic ontological concepts to be developed here are accordingly called “ existentiala”, among the most basic of which is being-in-the-world. As an ontological concept, this notion would function in place of, but in a manner not unlike, the concepts of substance and accident in the region of objects or things.

Consider the following diagram.

Just as the leaves being red is dependent on the categorial understanding of being as substance, “my experiencing of the leaves as red” is dependent on being-in-the-world. This implicit understanding (onto-logical) accompanies, although necessarily in an implicit manner, the lived experience (ontic) of my seeing the leaves. Both the unity and structure of the experience (in terms of the “I”, the act and the object) are determined by the unity and structural integrity of the phenomenon of being-in-the-world. But how? And what, in more detail, is this existentiale of being-in-the-world?

The “world” might be considered the referential component of being-in-the-world. It is that towards which Dasein’s being moves in its existence. The world should not, however, be understood as the sum total of all objects and possible relationships among them that do or might exist. The world, for Heidegger, belongs to Dasein’s being. This expression tries to capture what we mean, for example, when talking about the world of an artist, of a person inhabiting a religious world, or of meeting someone who opened up the world of her family to me. Heidegger describes this as “that ‘ wherein’ a factical Dasein as such can be said to ‘live’” (BT 93). Note that the world, then, while a feature of Dasein, is not something subjective, some inner state or idea that stands between the self and the things that are. Living in a familial world is precisely what allows me, for example, to experience those around me as family.

The multiplicity of worlds, however, is not ultimately what Heidegger wants to uncover and describe. He is interested in the phenomenon of the world as such, in the “worldhood of the world”: “Worldhood itself may have as its modes whatever structural wholes any special ‘worlds’ may have at the time; but it embraces in itself the a priori character of worldhood in general” (BT 93). Are there certain universal and necessary structures that belong to any and all worlds, remembering that “worlds” here means not objects or entities as such but that contextual milieu of meaning towards which Dasein is in its being?

In order to uncover such a priori structures, Heidegger turns not towards some special or privileged way of being-in or toward a world, inhabited only at certain moments or times. Instead, what must provide the beginning point for such a “transcendental” analysis is the everyday world in which we continually live, that which is closest to us and out of which other sorts of worlds might emerge: the everyday world of our ordinary surroundings (Umwelt). To begin anywhere else would be a mistake for at least two reasons. Were we to choose something like “perception” in the traditional sense of the term and talk about the world of those who see (versus, for example, the world of the blind), or were we to begin with the act of knowing and the world of the theoretician, we would mistake a part for the whole, a particular world and way of being worldly for the world as such. Secondly, such beginning points would covertly import into the analyses an understanding of being as substance or presence-at-hand, and so cover over the genuinely existential nature of Dasein’s being-in-the-world. Or, as Heidegger is at great pains to remind the reader, “worldhood itself is an existentiale” (BT 92).

This everyday world is not one of theoretical contemplation, of trying to describe the way things “look” or to “see” the causal connections between events, but one of practical engagement. Before, and even while, I looked out of the window to describe the leaves of the maple as an object in my field of vision, I was busied with the computer’s keyboard, a pencil, papers, books, the clutter of the desktop, a place for my coffee mug, shifting my own body in a less than comfortable chair and so forth. I get up and walk across the room to adjust the blinds, stepping past a filing cabinet and a rocking chair whose frayed wicker back catches the tip of my fingernail. These “things” with which I deal disclose themselves not as objects to be looked at from the outside, nor as entities that might exist “in themselves” were I not there. To take them that way requires an extraordinary amount of abstraction and theoretical positioning on my part. That such abstraction from the experience of being engaged in a concernful way with the “gear” or “equipment” (das Zeug) of the everyday world comes so easily and “naturally” testifies not to the efficacy of such abstraction, but to the sway of the categorial understanding into which I, as a historically, linguistically and culturally constituted Dasein, so naturally “fall”. The phenomenological challenge, one might say, is precisely to arrest this “natural” tendency, one that is grounded in the very being of Dasein.

Uncovering the worldhood of the world entails disclosing those structures that belong to and make possible my engagement with the everyday surrounding world. If I were to describe, for example, the window in my study as encountered in my everyday engagement with it, little heed would be paid to the colour or composition of its frame, to the length, width or weight of the glass. My “experience”, rather, is that I am hurriedly closing the window to keep out the rain from an early summer squall. Or, later, I am sliding it open to welcome the now shockingly cool air into a hot and stuffy apartment. What makes possible the window being what it is as a window, or as Heidegger puts it at one point, that “from which it acquires its specific Thingly character” (BT 98), are the structures constitutive of the worldhood of the world (along with our understanding of those structures).

These a priori structures of worldhood can be sketched out as follows: “with … in … in order to … for the sake of …”. That is, I am engaged with the window in the act of opening in order to let in the cool air for the sake of my own comfort. I am busy with the remote control in pushing what I hope is the right button in order to mute the sound for the sake of my peace of mind. Heidegger calls this structural totality an “assignment-context” in that the implement encountered is always within a context of assignments: the window, for example, is assigned (or refers to) the work or task (opening, closing, etc.), to the more immediate goal (letting in air), as well as referring to myself and others (my or our comfort) and even to nature at large (the lightness of the window as it slides up or down as a function of the stuff of which it is made, along with the window as a way of handling weather).

The key idea, however, is that these structures of the worldhood of the world are a priori in the sense of being necessary and universal. Imaginatively attempt to eliminate them and the everyday world collapses. Or from the side of the one who is “in” such a world, someone who failed to understand those structures, not theoretically but practically and implicitly, could never encounter a tool or piece of equipment as such. At best, he or she might simply gaze blankly at it. But this would be the empty gaze not of someone who did not understand what it was “for” (the assignment-context), but of someone who did not even understand the idea of things being-for something. These structures are the necessary conditions in the absence of which the world ceases to be.

The universality characterizing these structures is not only that they belong to any and all everyday surrounding worlds (whether I am opening a window, driving a car, moving furniture, etc.). For even when I supposedly go beyond the world of everyday praxis, when I come to inhabit the theoretical domains of science, mathematics, logic and so forth, these structures still hold sway. They are not transcended, but only modified. The scientist is still busy with a spectroscope in the act of observing in order to determine the wavelengths of light emitted by a certain compound for the sake of our knowing its chemical composition. Even the formal logician is still engaged with the logical law of the disjunctive syllogism in applying it to a certain line of a proof in order to demonstrate the validity of an argument for the sake of establishing our certainty of a conclusion. In other words, even when we withhold ourselves from what might be termed our everyday practical engagement with “things” so as just to observe how they are from a theoretical perspective, we do not suspend the functioning of the worldhood of the world. The theoretical world of things that are just present for an observer is a particular modification of, and remains grounded in, the everyday worldhood of the world.

The world, then, is that through which beings are “determined” as beings (tools): that through which they are “freed” for their being. Heidegger wants to identify the world or its worldhood not with being, but rather with being as understood in a certain manner. This understanding of being, in contrast to understanding being as presence-at-hand, is described as “readiness-to-hand” (Zuhandenheit), an expression that captures the serviceability or usability connotations that belong to the very being of implements. And the tacit understanding of readiness-to-hand, the “feel” for these structures that lingers in and holds them open, is what Heidegger calls “circumspection”.

But in calling attention to circumspection, a second moment of the triadic structure of being-in-the-world comes to the fore: the phenomenon of being-in. Circumspection is a particular understanding of being (in contrast to being as understood) and as such a mode of being-in. This “understanding of” Heidegger describes as disclosure, an opening up of what was closed off or hidden. The act of circumspective concern does not create the structures of worldhood, the assignment context, but rather illuminates or holds them open. Being-in “is itself the clearing”, the Da of Dasein, and an analysis of this phenomenon of Being-in would entail an explication of “the existential constitution of the ‘there’” (BT 171).

Being-in, like the world, is an existentiale. Accordingly, “in” here cannot mean a kind of objective, spatial relationship as when I might talk about my jacket being in the closet which is in the bedroom, in the apartment I have in Baltimore. Just as the world should not be understood categorially as the totality of objects, “in” must also be given an existential sense. To get the feel for this, Heidegger appeals to the sense of “being-in” as dwelling, residing among or being familiar with. This sense of “in” is what is expressed, for example, when I say that I am in to jazz, or that I just cannot get in to living in suburbia. One might object that such expressions are metaphorical: that the literal meaning of “in”, the primary meaning on which the metaphors draw and expand, is the “in” of objects and objective space. But Heidegger wants to claim precisely the opposite: that the original sense of “in” is the existential one and the “objective” or literal derivative – a modification of meaning that is the result of a shift from practical engagement with gear of the surrounding lifeworld to a theoretical attitude, one that substitutes for the particularities of dwelling and place the homogeneous expanse of Euclidean space.

Understanding (Verstehen), as has already been suggested, is one way in which this being-in is realized. But understanding is always complemented and accompanied by another mode of being-in, that of state-of-mind (Befindlichkeit). Heidegger describes these two constitutive structures of being-in as “equiprimordial”, in the sense that they are equally important and elemental in their capacities to disclose the world. One way of viewing these two modes of being-in might be as existential analogues to what Kant, with reference to the theoretical domain, called the two sources of knowledge: namely, sensibility and understanding. Our capacity to be affected by objects, the moment of receptivity in and through which objects are given, is what Kant called sensibility. Understanding, in turn, was that faculty through which the objects given in sensibility come to be thought conceptually. Sensibility for Kant testified to the situated nature of our experience: that we do not create the world but always already (time) find ourselves in (space) it.

It is just this notion of “always already being in” that Heidegger highlights with his existentiale of state-of-mind. Our being is something to which, as Heidegger says, we are delivered over. There is an elemental “givenness” about my existence. It erupts into the world beyond my control. I did not ask to be born, to be born white and male and of the parents and in the place where I was. This brute facticity saturates my Dasein, although not just in the sense of some distant past (see Chapter 1). It is as an ongoing phenomenon continually accompanying my Being-in-the-world. Heidegger describes this feature as a “thrownness” in the sense that I might mean, for example, when speaking about being thrown into a situation that was not of my making. “The expression ‘thrownness’ is meant to suggest the facticity of its being delivered over” (BT 174). Each and every moment of each and every day my being is something to which I have been delivered over as something already there that must be taken up. And it is this phenomenon that is disclosed by state-of-mind in a way that no amount of thought or conceptualization could accomplish. Moods, for Heidegger, are the various concrete ways in which state-of-mind gets worked out. State-of-mind (Befindlichkeit), with its resonance in German of how one already finds oneself, is our affective capacity to have or be in moods. My moods are intimately mine, yet still they happen to me. I find myself already in them, whether they be good moods, bad moods or the feel of pallid indifference that might accompany me much of the time. For Heidegger it is the disclosive capacity of moods, as ways in which being-in as state-of-mind is realized, that is crucial. As disclosive, they are ontologically revelatory of an irreducible existential “that-ness”, a profound and deep finitude that engulfs and qualifies my being-in all the way down to its very roots.2

But such elemental facticity is intertwined with potentiality: “Dasein is Being-possible which has been delivered over it to itself – thrown possibility through and through” (BT 183). Understanding, the complement of and continually accompanied by state-of-mind, is fundamentally the projection of possibilities. Circumspection, for example, is one way in which understanding uncovers tools for their possible us ability, for their service ability. This understanding of being as readiness-to-hand frees entities for their involvement and for the array of possible ways they can be. The window I engage with is the kind of thing that can be closed and opened and a source of needed light and a distraction and an occasion for vulnerability in an urban landscape and an example of a being that can be all these things.

When the tacit work of understanding becomes explicit, the network of assignment-relationships opened up through its projection come to be laid out. Such laying-out is what Heidegger calls interpretation (Auslegung). Note then that for Heidegger, “interpretation” does not have its usual sense of the imposition of subjective meaning, individual or collective, on things that somehow are already there “in themselves”. Understanding is what first makes possible that encounter with beings at all. The very idea of “being in itself” is a function of a certain implicit (and for Heidegger derivative) understanding of being that, when laid out explicitly, comes to be interpreted as substance and as pure presence-at-hand. Interpretation does not create but makes explicit this prior “as”.

At the same time, Dasein does not just understand the being of the entities it concerns itself with in the world, but it understands itself as well as being-in-the-world. If state-of-mind illuminates my intractable facticity and finitude (my always already having been), understanding discloses my potentiality-for-being (my not yet). Dasein is both the point of origin and return in this projective, affective understanding. The understanding of being that arises in Dasein has, as its terminus (the final term in the “with … in … in order to … for the sake of …” network of assignment references), Dasein itself. In my fumbling with a screwdriver in trying to loosen a frozen fixture in order to stop the tap from leaking, it is “for the sake of” my possible convenience. I understand myself in terms of my possibilities for being, projecting myself towards what I might or could or can be. Note that this need not imply a narrow egocentric interpretation. The same ontological structures could just as well make possible the final referent as “for the sake of” my child’s ability to sleep peacefully or for conserving our water supply. In the latter cases I understand myself as being-in a familial or a communal world, but it is my (Dasein’s) self-understanding.

But “who” then is this Dasein? We are now led from the world and its worldhood, through being-in as state-of-mind and understanding, to the third essential moment of the phenomenon of being-in-the-world: to “an approach to the existential question of the ‘who’ of Dasein” (BT 150). The theme taken up here is in many respects an old and well worn one: the topic of personal identity. Previous treatments have been legion. In Descartes, for example, recourse is made to a type of substantive soul, a res beneath the cogitans. Kant posited a necessary “unity of apperception”, an “I think” that must accompany all experience. Husserl sometimes spoke of an “ego-pole” from which the illuminating rays of consciousness emanate. Such accounts, according to Heidegger, presuppose and are nourished by a categorial understanding of being as presence-at-hand.

An existential treatment of the “I-ness of the I” must proceed along a different path. From the outset, in first indicating in a merely formal way the unique kind of being that belongs to Dasein, Heidegger says: “That Being which is an issue for this entity in its very Being, is in each case mine …. Because Dasein has in each case mineness (Jemeinigkeit), one must always use a personal pronoun when one addresses it: ‘I am’, ‘you are’” (BT 68). When asked, for example, “who’s there?” there’s only one answer: “Me”. The “who” of Dasein’s being-in-the-world, expressed ontically by the term “I”, is tinged by an almost ineffably intimate “mineness”. “I am” not just a person (an instance of a universal or general type), nor even just this particular person (as differentiated from all others because of singularities of genetics and life experiences). For this particular person is me. Reminiscent of points made in the indirect and pseudonymous writings of Kierkegaard, the categories of universal and particular fail to disclose this phenomenon. “Mineness” is an existentiale.

Authenticity and inauthenticity are possible modes of being for Dasein because of the “mineness” of my being-in-the-world. These terms, “authentic” (eigentlich) and “inauthentic” (uneigentlich), contain the German root “eigen” (own), and Heidegger says explicitly that he chose them precisely for that reason. I can be my own self or not be my own self only because this self is mine in the first place. And even when not being my own self, the foundational phenomenon of mineness does not somehow dissolve. Not being my own self is precisely one way, and even the predominant way, in which the phenomenon of mineness is worked out in my everyday being-in-the-world.

For example, it might be fair to say that for the most part my everyday existence is characterized by a deep-seated and powerful habituality: a habituality that is only all too “natural” and even necessary for ordinary living. My life carries me along familiar paths walked by others. It is, of course, still my life. But I enact ways of thinking, feeling and choosing, take up ways of valuing and models of human excellence that, from childhood on, I have learned from others. “The Self of everyday Dasein is the they-self” (BT 167). Human existence is mimetic and the only way that I can come to myself is by absorbing and inhabiting, both consciously and unconsciously, these ways of others. This in no less true even for those acts of rebellion, non-conformity and gestures of alleged creativity occasioned perhaps by boredom, or the gnawing feeling of not fitting in or of being unfulfilled in the traditional roles that await me. One “habit of being” is exchanged for another that might be a better fit.

But what, then, of authenticity and of the authentic self which is its own self? Is such authenticity possible at all? If so, how? And what, first of all, would such a thing even mean? Significant portions of Division Two of Being and Time are devoted to an analysis of this theme in terms of anxiety, guilt, conscience, resoluteness, finitude and death, the details of which are far beyond the scope of this chapter. I shall say only enough to shed some light on this phenomenon as it relates directly to the “who” of Dasein as being-in-the-world.

At the end of Heidegger’s initial treatment of the “who” or “I” of Dasein in Division One of Being and Time, he offers the following synopsis: “Authentic Being-one’s-Self does not rest upon an exceptional condition of the subject, a condition that has been detached from the ‘they’; it is rather an existentiellmodification of the ‘they’ – of the ‘they’ as an essential existential” (BT 168). Authenticity is spoken of here as a modification of, rather than an escape or detachment from, the inauthentic they-self. And the latter is said to be an essential constitutive feature of Dasein’s being-in-the-world. The authentic “I” should not, then, be understood as some deep, inner, “real” me: that special part of myself that only I can truly come to know. Nor in terms of a Romantic ideal of a self who, like Rousseau’s “noble savage”, lives uncontaminated by the ways of culture and civilization. Authentic understanding, authentic being-in-the-world, is predicated on a lucid self-awareness of the truth of Dasein’s being, a being that is cultural, historical and social. Kant, for example, drew the distinction between heteronomy (determined by the law of others) and autonomy (giving law to oneself). A glimmer of the distinction between the inauthentic and authentic, between the otherness of “the-they” and my own, appears here. But for Kant, human being is constituted by and realized in pure forms of rationality. To be autonomous, for Kant, is to be one’s ownmost self as rational. For Heidegger, Dasein has no such pre-given, inherently rational nature. Dasein’s essence is its Existenz, which is an issue or question for it, characterized by a thrownness and temporal finitude: a being that is “delivered over to itself” and is responsible for what it makes of that. The lucid realization that my “Dasein as being-in-the-world” is “without ground”, a truth from which I flee in the habitual “dispersal” into the they-self, provides the possibility for what might be termed an “existential autonomy”, in which I take up the burden of, and responsibility for, my existence, as being-with others, where “the-they” that still is me neither absorbs nor releases me from the responsibility for my ownmost being-in-the-world (see Chapter 4).

1. The ideas presented above draw heavily on Husserl’s distinction between categorial and sensuous intuition as found in Investigation VI of his Logical Investigations (Husserl 1970). Heidegger cites these sections of the Logical Investigations as having an important influence on his early work.

2. Later in Being and Time, Heidegger analyses the mood of anxiety as singularly disclosive of Dasein’s being-toward-death, its mortal finitude. But all moods, I would suggest, testify to and reveal the essential finitude of Dasein’s being.

Husserl, E. 1970. Logical Investigations, J. Findlay (trans.). New York: Humanities Press.

See Heidegger’s Being and Time; The Essence of Reasons (see also PM 107–20); The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, pt I; History of the Concept of Time: Prolegomena; Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, esp. §IV. And see E. Husserl, Logical Investigations, J. Findlay (trans.) (New York: Humanities Press, 1970), vol. II, §2, ch. 6.

See Dreyfus (1992), Gelven (1970: esp. 43–88), and Polt (1999: esp. 23–84).