Thomas Sheehan

The term die Kehre – “the turn” – has an over-determined and complex history in Heidegger’s work and has led to major misunderstandings of his project. As Heidegger clearly says in Contributions to Philosophy (GA 65 = CP), the turn is simply the bond between Dasein and Sein. Therefore, the turn in its basic and proper sense is the central topic of Heidegger’s thought. It is not, as many think, the 1930s shift in Heidegger’s approach to his central topic. The Kehre in its basic and proper sense never “took place”, least of all in Heidegger’s thinking.1

I shall distinguish three meanings of “the turn”: (i) the basic and proper sense – the bond between Dasein and Sein; (ii) the 1930s shift in how Heidegger treated that bond; and (iii) the act of resolve as a transformation in one’s relation to that bond.

Because the turn is Heidegger’s central topic, explaining it entails reviewing the core of Heidegger’s thought. This chapter will attempt to do that within a new key, one that translates Heidegger’s technical terms out of an ontological and into a phenomenological register. That re-translation is the necessary prologue to understanding what the Kehre is and is not.

Some conventions: in referring to “the turn” (not “the turning”!) in this chapter, I shall favour the German word Kehre, which Heidegger interprets as the “reciprocity” (Gegenschwung) of Dasein’s need of Sein and Sein’s need of Dasein. The Latin reci-proci-tas means literally “back-and-forth-ness”, which is how Heidegger understands the tension or “oscillation” (Erzittern) between Dasein’s thrownness into and its sustaining of Sein.2 Also I shall sometimes use the technical term “world” as the name for Sein.3 As regards the structure of Being and Time, I shall use the formula “BT I.1–2” to abbreviate Part One, Divisions 1 and 2; and “BT I.3” to abbreviate the unpublished Part One, Division 3, “Time and Being”. Finally, I use “man” and “human being” as gender-neutral and as the most formal of indications of what Heidegger means by Dasein.4

Aron Gurwitsch correctly noted that the one and only issue of philosophy – including Heidegger’s philosophy – is the question of meaning (Sinn) (Gurwitsch 1947: 652). But on the other hand Heidegger’s key terms “being itself” and “the being of beings” come from a pre-phenomenological metaphysics of objective realism, and to that degree are an obstacle to understanding his project in general and the Kehre in particular. If one chooses (unwisely, in my view) to continue using those pre-phenomenological terms, one should be clear that Heidegger himself understood Sein phenomenologically, that is, within a reduction from being to meaning, both (a) as giving meaning to the meaningful (= das Sein des Seienden) and (b) as the meaning-giving source of the meaning of the meaningful (= das Ereignis).

When Heidegger speaks of das Seiende (“beings”), he is referring to things not as just existing-out-there (existens) but rather in so far as they make sense within human concerns and thus are meaningful and significant (bedeutsam, verständlich, sinnhaft). Even what is “just out there” (das Vorhandene) is meaningful as, for example, “what happens to be of no practical interest at the moment”. In short, das Seiende is “the meaningful”, and das Sein gives it meaning. To adapt Woody Allen’s phrase: meaning is just another way of spelling being.5

In his first course after the First World War, Heidegger made the point by asking his students what it is they directly encounter in lived experience. Is it beings? things? objects? values? No, he insisted. What one encounters is

the meaningful [das Bedeutsame] – that is what is primary, that is what is immediately in your face without any mental detour through a conceptual grasp of the thing. When you live in the world of first-hand experience, everything comes at you loaded with meaning, all over the place and all the time. Everything appears in a meaningful context, and that context gives the thing its meaning.

(GA 55/57: 73.1–5 = TDF 61.24–8)6

To underline the point Heidegger frequently refers to this phenomenological “being of beings” as das Anwesen des Anwesenden: the meaningful presence of whatever is meaningful. Likewise he glosses the Greek on and ousia as paron and parousia, that is, not mere “beings” and their “beingness” but meaningful things and their meaningfulness.

Let us then revisit Aristotle’s famous sentence about the meanings of the word “being”: “The term ‘being’ has many meanings, but all of them point analogically toward one thing, one single nature” (Metaphysics IV 2, 1003a33–4). Read in a phenomenological key, that says:

The word “meaningful” has many senses, but all of them point analogically toward a unified “meaning itself” [Sein selbst as Ereignis] that is the source of all meaning.

Before applying all of this to the Kehre, and in order to emphasize that Heidegger’s work is anchored in a framework of meaning, I translate some of his terminology out of the usual ontological register into a phenomenological one (see Table 1).

The following may suffice for now:

1. All the terms in the chart have the character of what Aristotle calls to proteron tēi physei and to ti ēn einai, that is, that which, in any given situation, is always-already (a priori) operative. The terms in section II name the a priori process of meaning-giving. This process has no chronological date: it does not occur only occasionally but is always-already operative. It is the basic structural factum that is a priori at work in conjunction with human being.7

2. The terms in section II refer to the meaning-giving source of the meaningfulness of things. However, this source is not some hypostasis separate from and lying behind the meaning of the meaningful. Rather, the genitive in such phrases as Wesen/Lichtung/Wahrheit/Da des Seins indicates a pleonasm: Sein selbst is its Wesen/Lichtung/Wahrheit/Da. That is, Seyn (das Wesen des Seins) is the a priori condition whereby things get their meanings. And such meaning-giving never happens apart from human being.

3. Readers who are uncomfortable with the translations in the chart can simply substitute – without any damage to the argument – the traditional Heideggerian code words for the terms I use here, namely, be-ing / beyng, being itself, being, beingness, and beings; the swaying/destining/essencing/presencing/clearing/truth of being, along with enowning, enquivering, cleavage and the like.

The basic question motivating all of Heidegger’s work is quite simply “How does meaning occur at all?” (= the question about the Sinn/Wahrheit/Wesen des Seins). This basic question is focused on the meaning-giving source that enables (läßt sein) the meaning of things. Notice the crucial distinction between Heidegger’s lead-in question about the meaning of the meaningful (die Seiendheit des Seienden), and his basic question about the meaning-giving source of the meaning of the meaningful (Grundfrage: das Ereignis).8

1. The meaningfulness of the meaningful refers to the simple but astonishing fact that things are meaningful at all. Heidegger called this “the wonder of all wonders: that things make sense” (PM 234.18).9 This lead-in issue is the traditional one about on hēi on or ens qua ens, but now understood in a phenomenological mode: “What is the most basic structure of the things we encounter?”, to which Heidegger answers, “Things as such are meaningful: they make sense”.

2. The meaning-giving source of the meaning of the meaningful – also called “meaning itself” or “meaning as such” – refers to the a priori process whereby anything meaningful has its meaning. The early Heidegger analysed this source-of-meaning as the bond of “beingin” and “world”. This is the man–meaning bond that he originally called being-in-the-world (In-der-Welt-sein) and later on called Lichtung-sein (GA 69: 101.12). This man–meaning phenomenon will eventually be named Ereignis, the appropriating of man to the task of sustaining meaning-giving (GA 65: 261.25–6 = CP 184.27–9; see also Chapter 10).

To put this in schematic form, Heidegger’s basic question was about the source of his lead-in issue.

The Grundfrage concerns the meaning-giving source:

| The | |||

| Anwesen-lassen | letting-come-about | ||

| Es gibt | a priori givenness | ||

| Schickung/Geschick | giving/givenness | ||

| Seyn | coming-to-pass | ||

| Wahrheit | disclosure | ||

| Welt | world | ||

of

the meaning of the meaningful

die Bedeutung des Bedeutsamen

das Anwesen des Anwesenden

das Sein des Seienden

Regardless of the terms given here, the phrase “meaning-giving source” is merely heuristic at this point. It names an unknown “X” that motivates and guides the basic question while remaining as yet undetermined. But whatever it might turn out to be, the meaning-giving source is operative only in and with human being. In 1955 Heidegger insisted that just as the process of meaning-giving constitutes man, so too man co-constitutes the process of meaning-giving.

We always say too little of “meaning [Sein] itself” when in saying “meaning”, we leave out its presence in and with human being and thereby fail to recognize that human being itself co-constitutes [mitausmacht] “meaning”. We also always say too little of human being if, in saying “meaning” …, we posit human being for itself and only then bring what has been so posited into a relation with “meaning”.

(GA 9: 407.22–8 = PM 308.3–9)10

At the beginning I remarked that “Kehre” is an over-determined word in Heidegger’s work. It is now time to explain what that means. Richard Rorty was fond of saying, “When your argument hits a wall, make some distinctions.” And distinctions indeed must be made because, in keeping with Aristotelian pros hen analogy, Heidegger used the word Kehre in many distinct senses, all of them related to one basic, proper sense. Just as there is the analogy of being, or meaning, so likewise there is the analogy of Kehre.

What I have said about the Kehre up to this point – that it is the reciprocal bond of Dasein-Sein – is based on Heidegger’s Contributions to Philosophy, written in 1936–8. That is, I have been dealing exclusively with the basic and proper sense of Kehre: the reciprocity or tension between man’s being required for and man’s holding open the fundamental factum of meaning-giving. Throughout his career, however, Heidegger used the term Kehre in at least two other senses that are analogically related to but not identical with the basic sense. To keep things distinct, I shall use “Kehre-1” to designate the basic Kehre discussed in Contributions, and shall designate the other meanings of Kehre by subsequent numbers.

In 1969 Heidegger stated simply and directly what the central topic of all his thinking was.

The basic idea of my thinking is precisely that meaning [Sein], i.e. the process of meaning-giving [die Offenbarkeit des Seins], requires human being; and conversely that human being is human in so far as it stands in [i.e. sustains] the process of meaning-giving.

(GA 16: 704.1–5 = MHC 82.30–33)

In short, Heidegger’s central topic is the man–meaning bond as allowing things their meaning. Throughout his later work Heidegger will use two key terms to name that bond. Human being, he writes, is (i) required (gebraucht) (ii) to belong to (zugehören, i.e. to sustain) the world (GA 65: 251.24–5 = CP 177.30–31).11 These two terms – Brauch and Zugehören – parallel the early Heidegger’s terms “thrownness” (Geworfenheit) and “projectively holding open” (Entwurf) (GA 65: 261.1–3 = CP 186.7–10).12

Man is by nature hermeneutical, ever in need of meaning and ever making meaning possible (cf. GA 21: 151.4–5).13 Meaning is man’s life-breath. Take it away, obliterate its source, and there is no human being left. Correlatively, in order to operate at all, meaning requires human being as its grounding “where”. Without Sein there is no Dasein. Without Dasein there is no Sein. Man must be claimed for, or appropriated to, or thrown into, sustaining the a priori process of meaning-giving. And as claimed/appropriated/thrown, man is required to projectively hold open meaning-giving. The tension of those two is the fundamental factum, the Kehre in its basic and proper sense. Heidegger writes:

Appropriation has its innermost occurrence and its widest reach in the turn. The turn that is a priori operative in appropriation is the hidden ground of all other subordinate turns, circles, and circularities, which themselves are obscure in their provenance, remain unquestioned, and are easily taken in themselves as the “ultimate”.

(GA 65: 264.1–3 = CP 186.7–9)

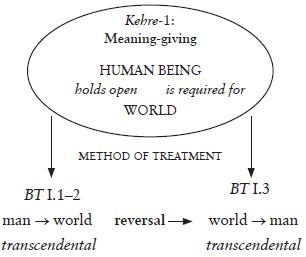

In Being and Time the analysis of the meaning-giving reciprocity was to be treated in two steps, respectively in BT I.1–2 and in BT I.3.

Figure 1 (opposite) shows, within the oval, the two ways in which human being is a priori related to world: (a) “actively”, by projectively holding open, sustaining, and grounding the meaning-giving world; and (b) “passively”, in so far as man is claimed by or thrown into sustaining the world. Everything within the oval is the fundamental structural factum. Outside the oval are the places where and the modes in which Heidegger planned to analyse that factum.

Outside the oval: From the beginning Heidegger had already programmed into his work a reversal of direction (Umkehrung) between I.1–2 and I.3. Being and Time would emphasize Dasein (= BT I.1–2). Only then would it reverse direction and emphasize Sein (= BT I.3). The first step would show how human being projectively holds the world open. The second step (the reversal) would show how the meaning-giving world requires human being, such that man is thrown into the meaning-giving process. Both steps were to be worked out in a transcendental–horizonal framework in which human being is understood as projecting the horizon (opening the arena) of meaning-giving.

Heidegger made a first stab at BT I.3 in his 1927 course “Basic Problems of Phenomenology”, where he continued to use the transcendental–horizonal approach of BT 1.1–2. However, the effort made little progress, and at that point Heidegger’s plan to work out BT I.3 within a transcendental framework collapsed.

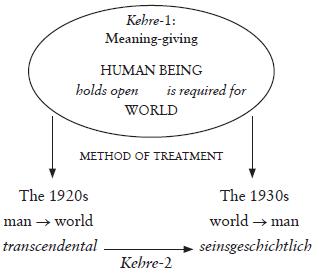

Shortly after publishing Being and Time Heidegger began shifting his method for treating the second step in his programme, the reversal of direction. Instead of a consistent transcendental approach in both steps, Heidegger adopted what he called a seinsgeschichtlich approach to BT I.3. This shift in treatment constitutes Kehre-2, of which William J. Richardson’s Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought (2003) is the authoritative treatment. As Heidegger writes in “Letter on Humanism” (1947), BT I.3 was foreseen as the place “where the whole project gets reversed [sich umkehrt] as regards the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ both of thinking and of what is thought-worthy“(GA 9: 328.2 with n.a = PM 250.1 with n.a).14

The reversal that Heidegger is talking about is the already planned reversal of direction from man → world to world → man. However, that second step, “Time and Being”, “was held back because my thinking failed to adequately express this reversal and did not succeed with the [transcendental] language of metaphysics” (GA 9: 327.32–328.4 = PM 249.37–250.4).

In the mid 1930s, as a result of the inability of transcendental thinking to express the reversal of direction programmed for BT I.3, Heidegger changed his way of treating the second step of the process from a transcendental–horizonal to a seinsgeschichtlich approach centred on how man is required for meaning-giving to be operative at all. In Figure 2, note that Kehre-2 stands outside the oval: it is merely a way of treating Kehre-1 and is not at all identical with the basic and proper sense of the turn.15 Note as well the shift from a transcendental to a seinsgeschichtlich approach, which constitutes Kehre-2.

Usually mistranslated as “being-historical”, the term seinsgeschichtlich has nothing to do with history and everything to do with Es gibt Sein (GA 46: 94.11–14). We may translate that latter phrase as: “Meaning-giving is a priori operative wherever there is human being” – which means that the Schickung/Geschick des Seins (the “sending” or “giving” of meaning) is the same as the meaning-giving bond of man–meaning. The presupposition of the seinsgeschichtlich approach is that meaning is always-already given with human being itself rather than through some projective activity on the part of this or that person. Moreover, the emphasis now is less on man projectively holding open the world and more on man’s being required to hold open the world. On this seinsgeschichtlich basis the later Heidegger could bring the work of BT I.3 to fruition outside the limitations of transcendental method.

Figure 2.

There are two texts that, taken together, clarify the new seinsgeschichtlich approach: first, a note in Being and Time, and secondly, the 1930 essay “On the Essence of Truth”.

As regards the first text, in a crucial marginal note that he added to Being and Time §9 (“The Outline of the Treatise”), Heidegger spells out the formal stages in the progression of Kehre-2. The numbers here are mine.

1. The transcendental difference.

2. Overcoming the horizon as such.

3. The turn around into the source.

4. Meaning from out of this source.16

This note outlines the four steps that go to make up Kehre-2.

Number 1 refers to the transcendental framework of Being and Time and of Heidegger’s courses and shorter works up to the autumn of 1930. The transcendental difference is an early name for the “ontological difference” and is the distinction between the meaning-giving world sustained by human being and whatever shows up within that world.

Number 2 refers to Kehre-2, the shift from the transcendental to the seinsgeschichtlich approach for working out “Time and Being”.17 Note that this step entails overcoming the horizon as such – that is, in so far as it is taken as a transcendental horizon – while leaving that field intact for further seinsgeschichtlich investigation. In other words, the gains of BT I.1–2 – the temporal holding-open of world – remain in place, but the sequel (BT I.3) ceases to use a transcendental–horizonal approach.

Number 3 refers to the seinsgeschichtlich working out of BT I.3 (= Kehre-2) and specifically the turn of the analysis to a focus on the abiding source of meaning-giving while, in the process (and as already planned), reversing the approach from man → meaning to meaning → man.

Number 4 refers to the outcome of the analysis: an understanding and acceptance of the fact that all meaning derives from the finite meaning-giving source, which soon will be called Ereignis, the a priori “appropriation” of man for sustaining meaning-giving.

To conclude, from this marginal note it is clear that Heidegger’s central topic, Kehre-1, remains unchanged even while the method for treating it shifts from transcendental to seinsgeschichtlich (GA 9: 328.7–8 with n.c = PM 250.7–8 with n.c).

As regards the second text, Heidegger says that his 1930 essay “On the Essence of Truth” already offered “a certain insight into the thinking of the Kehre from ‘Being and Time’ to ‘Time and Being’” (GA 9: 4–8 = PM 250.4–7).18 Heidegger is referring here to Kehre-2, the shift to a seinsgeschichtlich approach. The question now is where and how Kehre-2 fits into the 1930 essay and what the shift in the “thought-worthy” consists in.

“On the Essence of Truth” demonstrates two things:

1. Truth as correspondence is made possible by human freedom, which is man’s a priori relatedness to the meaningful (= sections 1–5 of “On the Essence of Truth”).

2. Human being is bound up with two newly formulated dimensions of the hiddenness of the meaning-giving source (= sections 6–7 of the essay):

3. the source as intrinsically concealed (Verbergung as the “mystery”);

4. the source as overlooked and forgotten (Irre).

With some effort one can recognize that point 1 is cognate with BT I.1–2, namely, human being as sustaining the meaning-giving world, man as alētheia and Zeitlichkeit. But in 2(a) Heidegger adds a new dimension to BT I.3 by showing that the source of all meaning is intrinsically “concealed” (i.e. unknowable in the strict sense of the term) if only because in order to know what meaning-giving is, we would have to presuppose that very meaning-giving itself. At best we can only experience that the source is, without knowing what is responsible for it. We can sense our fate (facticity) as thrownness into finite and mortal meaning-giving and then either embrace it in an act of resolve (authenticity) or flee from our essential involvement in it (inauthenticity) (see Chapters 1 and 4). Moreover, as 2(b) argues, this concealed source of meaning is for the most part overlooked because it is intrinsically concealed.

According to Heidegger, between §5 and §6 of the essay – that is, between points 1 and 2 – there occurs “the leap into the Kehre that is a priori operative in appropriation” (GA 9: 193 n.a = PM 148 n.a).19 This simple phrase is actually quite complex. What Heidegger refers to as “the leap” corresponds to number 2 in the marginal note to Being and Time: the “leap” is Kehre-2. (He calls it a “leap” because he considers it impossible to make a smooth and simple transition from a transcendental to a seinsgeschichtlich approach.) However, the leap of Kehre-2 lands one in Kehre-1 along with the seinsgeschichtlich way of treating it. Thus “the leap into the Kehre that is a priori operative in appropriation” means overcoming the transcendental–horizonal approach of BT I.1–2 and starting afresh with the seinsgeschichtlich (“meaning-i s-already-given”) approach of BT I.3. And with that fresh start, and with his new recognition of the twofold hiddenness of the source, Heidegger says he finally arrived at the site from out of which he experienced and wrote Being and Time, namely, (i) the intrinsic hiddenness of the source of meaning and (ii) the overlooking and forgetting of that hiddenness (GA 9: 328.9–11 = PM 250.8–10).20

Heidegger summarizes the ultimate intent of “On the Essence of Truth” in a chiasmic thesis: Die Wahrheit des Wesens ist das Wesen der Wahrheit (GA 9: 201.3–19 = PM 153.27–154.2).21 To translate that sentence as “The truth of essence is the essence of truth” is to say nothing. Properly interpreted, the sentence says: “The process of meaning-giving” (die Wahrheit des Wesens) is “the source of truth-as-correspondence” (das Wesen der Wahrheit).

Unfortunately Heidegger’s less than precise language has contributed to the confusion between the Kehre-1 of Contributions to Philosophy and the Kehre-2 of “On the Essence of Truth” and “Letter on Humanism”. Heidegger finally came to distinguish clearly between the two only in his letter to William J. Richardson (April 1962) when he denominated Kehre-2 as a “shift” (Wendung) in his approach to the central topic, as contrasted with Kehre-1, which is operative in the very content (Sachverhalt) of the central topic (PMH xvii.25 [Wendung]; xix.6–7 [Sachverhalt]).22

A final note on Kehre-2: does a sentence like “Meaning-giving claims or calls man” risk anthropomorphizing the meaning-giving process? Yes, it does. Given Heidegger’s penchant for using anthropomorphic metaphors to express his central topic, there is always the danger of hypostasizing meaning-giving into a Super-Power endowed with agency, a cosmic Something that “does things” to human beings, such as “drawing” them into meaning-giving. For example, the later Heidegger will use the term Ereignis for the man–meaning bond. That technical term refers to the fact of meaning-giving in so far as it “requires” human being (brauchen) to belong to (zugehören) and sustain that fundamental fact. However, Ereignis is said to “appropriate and own” (ereignen) man as Sein’s own “property” (Eigentum), while in turn making possible man’s proper authenticity (Eigentlichkeit). Do all these metaphors mean that Ereignis is a Super-Something with power to act on human beings? If such a monstrosity is to be avoided at all costs, what then about the later Heidegger’s apparent quasi-hypostasization of Sein?

Richardson answers that question with exquisite délicatesse: “Only truly great philosophers should be indulged for their obscurity”.23

A final use of the word Kehre – we shall call it Kehre-3 – refers to the existentiell transformation (Verwandlung) of human beings and their worlds of meaning by way of an insight into Kehre-1 and a corresponding act of resolve. Heidegger himself points to this usage in his letter to Richardson. Arguing that Kehre-3 was at work in his thought as early as 1937–8 when he was in the process of carrying out Kehre-2, Heidegger quotes his own words from a lecture course he taught that winter:

Over and over again we have to insist: What is at stake in the question of truth … is a transformation in human being itself. … Man comes into question here in the deepest, broadest, and genuinely fundamental perspective: human being in relation to Seyn – i.e. in Kehre-2: Seyn and its truth in relation to human being. The determination of the essence of truth is accompanied by a necessary transformation of man. The two are the same.24

The existentiell–personal transformation that is Kehre-3 had actually been at issue as early as Being and Time, the motto of which was, in effect, “Become what you already are” (GA 2: 194.3 = BT 186.4).25 Heidegger understands that sentence as an exhortation coming from one’s own nature to become that very nature by way of a personal conversion from living inauthentically to becoming what and how one essentially is. Being and Time is ultimately meant as a phenomeno-logical protreptic to coming back to and taking over the facticity that defines human being.26 It is an exhortation to personally assume one’s hermeneutical mortality, one’s making sense of things while always living at the point of death.27 Only in such a radically first-person act of conversion is authentic meaning-giving at work.

If, in Being and Time, Kehre-3 was the radical transformation from self-alienation to liberation, in a later lecture entitled “Die Kehre” (1949) Heidegger steps back and takes a global view of the possibility of such a transformation in today’s Westernized world.28

Recall that Being and Time defined man as concernful and temporal being-in-the-world, thrown into sustaining meaning-giving. A world is a specific formation of meaning, a particular Geschick des Seins (given-ness of meaning) that is always-already operative in and with human being. To review:

1. Each world, as a meaning-giving field, requires a corresponding way of “being-in-it”, more precisely, a way of man’s being appropriated to sustaining that world. We may call the specific way of “being in” and “living” a world the existential ethos of that world. Sustaining a world existentially and living its ethos existentielly makes us “complicit” in that world’s mode of giving meaning to things.

2. The meaning-giving bond of man–meaning is intrinsically “hidden”, that is, unknowable in the strict sense (see above), even though we are able to sense our attunement to that particular formation of meaning (GA 46: 221.14–6).

3. Even though we are a priori appropriated to sustaining the worlds we live in, for the most part we overlook and forget the very man–meaning bond – the appropriation – that constitutes them. Early on, Heidegger called this condition “fallenness” and in the 1930s he called it “errance” (Irre).

In his 1949 lecture, Heidegger focuses on three issues: (i) how sense is made in the present formation of meaning; (ii) the danger that the present formation of meaning poses to the man–meaning bond; and (iii) the possibility of liberation from that danger by the “conversion” mentioned above.

Heidegger sees today’s Westernized man as locked into a global paradigm of meaning that he calls Ge-stell, which I translate as the “Construct” (see also Chapter 13).(Gestell is derived from Meister Eckhart’s neologism Gestellnis, which translates the Latin forma and ultimately the Greek morphē, namely, that as which something is construed.29) This growing global ethos, dominated as it is by techno-think (Technik), is characterized by a compulsion to construe everything as a mere resource to be exploited for consumption, whether that be nature (“raw material”) or human beings (“human resources”).

The paradox of the Construct is that in so far as human beings are appropriated to sustaining that specific formation of meaning, they ineluctably are complicit in and collaborate with the exploitation of themselves as well as of nature and each other. And yet all of this – the Construct, its ethos of exploitation, the techno-think that is its way of disclosure, and our essential complicity with all of that – is itself a Geschick des Seins, a gift of meaning that, like every other Geschick, overlooks and forgets appropriation, the hidden meaning-giving source of all meaning.

In the Construct, as in any other paradigm of meaning, the appropriation of human being that sustains the ethos of exploitation is “hidden” for the reasons given earlier. And as in any other Geschick des Seins, that hiddenness is generally overlooked. However, what is specific to the Construct’s form of appropriation is a third level of hiddenness. The lock that the Construct has on us owing to our complicity in its ethos of techno-think and exploitation effectively obscures the fact that we overlook our appropriation to it. The Construct traps us in a vicious circle that blinds us to any mode of appropriation and therefore occludes what Heidegger calls “the mystery of human being” (GA 9: 195.23 = PM 149.28), namely, human facticity as thrownness into sustaining the intrinsically hidden factum. And human being, as appropriated to sustaining the Construct, colludes in blocking any awareness of its exploitative appropriation, or of any other possible appropriation for that matter.

To summarize in the reverse order: in the current paradigm of meaning there is, then, a threefold hiding of Kehre-1. The Construct (i) effectively obliterates (ii) one’s overlooking and forgetting (iii) of the naturally hidden appropriation of oneself to sustaining any formation of meaning. The result is that today we are trapped in a prison of self-alienation.

Heidegger argues that although the Construct effectively blots out all traces of the true nature of man, it nonetheless harbours the possibility of a radical transformation of the Construct into another, non-exploitative paradigm (GA 79: 69.24–5 = QCT 39.3–4). Every Geschick des Seins holds the possibility of such a change in so far as the hidden and indomitable source of meaning (the Es gibt Sein) remains an inexhaustible treasure of yet further meaning-giving.30 Heidegger’s hope is that at least a few souls will experience what he calls a “brief glimpse into the mystery from out of errance” (GA 9: 198.21–2 = PM 151.36) – a flash of insight into the source of all meaning – and thus, by an act of resolve, will step through and beyond the Construct.31

Paradoxically he finds the possibility of liberation within the very danger posed by the Construct. Yes, the Construct is the Danger in so far as it imposes a virtually complete blackout of appropriation in any form. And yes, the result is a pervasive feeling of deep boredom, of profound alienation from the grip that meaning itself has on human being. Heidegger’s hope, however, is that this stifling atmosphere of alienation from one’s own nature will eventually lead to a personal epiphany in which one finally recognizes the danger as the danger it is and thereby awakens to one’s true nature. Being and Time couched such an epiphany in the language of a decisive Augenblick, a sudden insight into oneself as mortally bonded to meaning-giving. In the 1949 essay, the epiphany is discussed analogously in terms of a Blitz/Blick, a lightning-flash of insight (Heraclitus, fr. 64: keraunos) that can lead to the transformation of oneself and of the current world of meaning.32

We see, then, (i) that the intrinsic hiddenness of appropriation facilitates (and to that degree is responsible for) the overlooking of appropriation; (ii) that the gift of the current formation of meaning (which occludes its own source) is an ethos of disclosure that understands everything as an exploitable resource; and (iii) that all this adds up to the immense Danger of utter self-alienation. However, (iv) once the alienating power of that Danger is seen for what it is, the current self-endangering of the man–meaning bond can be transformed, at least for a few individuals, into a non-alienating world of meaning. Heidegger poses this possibility in Hölderlin’s words:

Where the danger expands, that which frees us Also grows

(“Patmos”, 3–4)

In the moment of insight, described as an epiphantic “lightning bolt”, an elite few who are now exploited and alienated might raise anew, within themselves and not merely in formal philosophy, the question that goes to the core of human being: how does meaning occur at all? At that point one might say with Heraclitus (fr. 119), ethos anthrēpōi daimoōn: to live authentically is to live the mystery of the thrown sustaining of meaning.

1. Citations in this chapter refer to texts by page and line, separated by a period. All translations are my own (see the glossary at the end of this chapter), but I shall refer the reader to the corresponding pages in existing English translations with an “=”. The present text corrects my earlier account (Sheehan 2000).

2. Gegenschwung, Gegenschwingen, Erschwingen: GA 65: 251.24, 261.25–6, 262.2–4, 263.19–20 = CP 177.30, 184.28–9 and 36–7, 185.38–9. (That last text shows that the gods are various formations/Geschicke of meaning.) On reci-proci-ty: GA 65: 381.26–7 = CP266.25. For Erzittern, GA 65: 262.9 = CP 185.3, et passim. Definitely not “enquivering”.

3. Compare GA 9: 332.3–4, “Die Lichtung selber aber ist das Sein” with GA 9: 326.15–6, “Die Lichtung des Seins, und nur sie, ist ‘Welt’” = PM 253.1 and 248.36–7 respectively.

4. GA 10: 128.13–14 = PR 86.20. Both “man” and “human being” translate the Greek anthrōpos understood as Dasein: human being in its a priori structure. On formal indication, see Dahlstrom (2001: 242–52).

5. See Allen’s comments on his film Matchpoint, Cannes, 12 May 2005, in Ebert (2005: 852).

6. When Heidegger says that “the world worlds” (die Welt weltet), he means that the world allows for the meaning of whatever is found within the world.

7. GA 65: 261.22–3 = CP 184.25–6: “Die Wahrheit des Seins und so dieses selbst west nur, wo and wann Da-sein”; GA 65: 263.28–9 = CP 186.3–4: “Das Seyn und die Wesung seiner Wahrheit ist des Menschen, sofern er inständlich wird als Da-sein”; GA 65: 264.1 = CP 186.3: “Das Sein ‘ist’ des Menschen”.

8. Meaning as such (Anwesen als solches) always entails meaning-giving (Anwesenlassen: GA 14: 45.29–30 = TB 37.5, where it is misprinted), just as in medieval philosophy, having esse always entails giving esse: “Omne ens actu natum est agere aliquid actu existens” (It is the nature of every being-in-act to effect something [else] existing in act) (Thomas Aquinas, Summa contra gentes, II, 6, no. 4). At GA 9: 369 = PM 280, note “d” equates Sein, Wahrheit, Welt,  Ereignis and Sichankündigen des Seins. GA 9: 201.30–2 = PM 154.12–4 equates Sinn, Entwurfbereich, Offenheit and Wahrheit as the meaning-giving source of the meaning of the meaningful. On “the last god” as die Wahrheit des Seyns, see GA 65: 35.2 = CP 25.16.

Ereignis and Sichankündigen des Seins. GA 9: 201.30–2 = PM 154.12–4 equates Sinn, Entwurfbereich, Offenheit and Wahrheit as the meaning-giving source of the meaning of the meaningful. On “the last god” as die Wahrheit des Seyns, see GA 65: 35.2 = CP 25.16.

9. In Heidegger-code: “daß Seiendes ist”: GA 9: 307.23–4= PM 234.18. See also GA 52: 64.24–5.

10. See also GA 9: 412.1–3 = PM 311.21–3). Also see GA 8: 85.13–9 = WCT 79.19–22. Thus, whenever I use “man” or “human being”, I intend them as completed by the word Sein – as in “man–meaning”.

11. With “sustain” I translate Heidegger’s (i)Entwurf als Offenhalten, “projection as holding open/sustaining”, (ii) ausstehen as at GA 9: 332.19 = PM 253.14, and in the sense of ausstehend at GA 65: 35.6–7 = CP 25.20.

12. Geworfenheit and Entwurf become gebraucht and wahren der Augenblicksstätte, respectively. Regarding thrownness as being-appropriated: “die Er-eignung, das Geworfenwerden”: GA 65: 34.9 = CP 24.32–3; “geworfener … er-eignet”: GA 65: 239.5 = CP 169.12. Heidegger sometimes refers to the interface of thrownness and holding-open as “kehrig”, that is, reciprocal: for example, GA 65: 261.29 = CP 184.32; GA 65: 265.26 = CP 187.21.

13. “Weil Dasein in seinem Sein selbst bedeutend ist, lebt es in Bedeutungen und kann sich als diese aussprechen”.

14. The change in thinking refers to abandoning the transcendental approach. The change in what is thought-worthy refers not just to the shift from BT I.1–2 to BT I.3, but more specifically to the world’s “claiming” man to sustain meaning-giving. The basic thought-worthy matter for Heidegger is always the factum of meaning-giving: GA 79: 70.28–9 = QCT40.11–12.

15. It is important to distinguish between (i) the reversal in the direction of the analysis, namely from man → world to world → man, which was programmed into BT from the start and which was initially intended to proceed within a transcendental framework, and (ii) the shift from a transcendental to a seinsgeschichtlich framework. Only the latter is Kehre-2.

16. “Die transzendenzhafte Differenz./Die Überwindung des Horizonts als solchen./Die Umkehr in die Herkunft./Das Anwesen aus dieser Herkunft” (GA 2: 53 n.a = BTS 35.33–5). For a variant story of the transition to the later work, see GA 65: §132 = CP §132. Heidegger first uses the term “ontological difference” in his 1929 essay “Vom Wesen des Grundes”. In this marginal note he uses the (presumably pre-1929) term “transcendental difference” in place of “ontological difference”. Regarding “transzendenzhaft” as “ontologisch”, see Müller (1949: 73–4).

17. See GA 65: 250.14–17 = CP 176.33–6: “Deshalb bedurfte es der Bemühung … die Wahrheit des Seyns aus dessen eigenem Wesen zu fassen (Ereignis)”.

18. “… gibt einen gewissen Einblick in das Denken der Kehre[−2] von ‘Sein und Zeit’ zu ‘Zeit und Sein’”.

19. “Zwischen 5. und 6. der Sprung in die (im Ereignis wesende) Kehre”.

20. “In ihr [= Kehre-2] gelangt das versuchte Denken erst in die Ortschaft der Dimension, aus der ‘Sein und Zeit’ erfahren ist, und zwar erfahren in der Grunderfahrung des Seinsvergessenheit” (GA 9: 328.9–11).

21. Although Heidegger presents the thesis in the reverse order to the above, he insists that the subject of the sentence is die Wahrheit des Wesens.

22. Also in GA 11: 149.21–2 and 149.34–5, respectively.

23. My thanks to my colleague Professor Richard Capobianco for the report of this bon mot.

24. The text first appeared in PMH xxi.7ff. It has since been published in GA 45: 214.15–27 = BQP 181.5–15.

25. “… werde, was du bist!” The phrase stems from Pindar’s Pythian Odes, II.72: genoi’ hoios essi mathēn.

26. Coming back to and taking over: GA 2: 194.3; 431.13, 21–2, 34; 506.21–2; 524.2 = BT 186.4; 373.16, 21–2; 374.7; 434.34–5; 448.34.

27. Human being makes sense of things because it is mortal. Making sense means “taking X as …”, that is, synthesizing “over” (i.e. both despite and because of) separation (diairesis). The ultimate separation “over which” we synthesize (i.e. make sense) is our own death. I translate Sein-zum-Tode as “being at the point of death”.

28. Note that in 1952 Heidegger calls Kehre-3 a Wende, “a turn today against the raging of the technological world” (MLS 281.17–18 = LW 228.14–15).

29. GA 81: 286.6–10. See GA 9: 276.6 = PM 211.5. “Construct” is derived from the Latin construere, to pile up and arrange.

30. See GA 65: 241.17–8 = CP 170.34–5: die Verweigerung = die erste höchste Schenkung des Seyns; and GA 65: 246.17–9 = CP 174.6–8: das Sichentziehende as höchste Schenkung.

31. “A few”: GA 65: §5 = CP §5. Also “Das stille Einverständnis Weniger”, MLS 208.9–10 = LW 163.9.

32. Note that, in the lightning flash of insight, what shows itself/comes to pass is world: GA 79: 73.13 and 74.25 = QCT43.22 and 45.13–6. Glossary of translations and paraphrases

| Anwesen | meaning-giving; traditionally: presence |

| Anwesendes | the meaningful; traditionally: present beings |

| Da des Seins | “where” [the meaning-process occurs]; traditionally: the t/here of being |

| Dasein | human being; man [in a gender-undifferentiated sense]; the “where” [meaning occurs]; traditionally: being-there; being-t/here |

| entwerfen | to sustain or hold open [meaning-giving]; traditionally: to project, project open |

| Ereignis | appropriation; traditionally: the event of appropriation |

| Es gibt Sein | meaning-giving occurs with human being; traditionally: it gives Being, there is Being |

| Gegenschwung | reciprocity; traditionally: counter-resonance |

| Geschick | a formation of meaning-giving; traditionally: a destiny of being |

| Ge-stell | Construct; traditionally: enframing |

| In-der-Welt-sein | being a priori in meaning; traditionally: being-in-the-world |

| ist | [something] makes sense; traditionally: [something] is |

| Kehre | the turn; traditionally: the turning |

| Kehre-1 | the man–meaning bond |

| Kehre-2 | the reversal of direction [from man to meaning] |

| Kehre-3 | the transformation of man [from fallenness and inauthenticity to authenticity] |

| kehrig | reciprocal; traditionally: turning (adj.) |

| Lichtung | the process of meaning-giving; traditionally: the clearing |

| Offenbarkeit des Seins | the process of meaning-giving; traditionally: the openness/revealedness of being |

| offenhalten | to sustain/hold open the meaning-giving process |

| Seiendes | the meaningful; traditionally: beings |

| Seiendheit | meaningfulness; traditionally: beingness |

| Sein | meaning-giving; traditionally: being |

| Technik | techno-think; traditionally: technicity, technology |

| Umkehr | reversal [of direction]; cf. Wende/Wendung |

| verstehen | to make sense of; traditionally: to understand |

| Wahrheit | the process of meaning-giving; traditionally: truth |

| Welt | meaning-giving context, world; traditionally: world |

| Die Welt weltet | the meaning-giving context gives meaning; traditionally: the world worlds |

| Wende/Wendung | shift [of direction]; cf. Umkehr and Kehre-2 |

| Wesen | the occurrence of meaning-giving; traditionally essence, essencing; essential sway |

Dahlstrom, D. O. 2001. Heidegger’s Concept of Truth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ebert, R. 2005. Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook, 2006. Riverside, NJ: Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Gurwitsch, A. 1947. “Review of Gaston Berger, Le cogito dans la philosophie de Husserl”. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 7(4) (June): 649–654.

Müller, M. 1949. Existenzphilosophie im geistigen Leben der Gegenwart. Heidelberg: F. H. Kerle.

Richardson, W. J. 2003. Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought, 4th edn. New York: Fordham University Press.

Sheehan, T. 2000. “Kehre and Ereignis”. In A Companion to Heidegger’s Introduction to Metaphysics, R. Polt & G. Fried (eds), 3–16, 263–274. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

See Heidegger’s “The Turning”, in The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays, 36–49; “On the Essence of Truth”, in Pathmarks, 136–154; and “Letter on Humanism”, in Pathmarks, 239–276.

See Richardson (2003). See also J. Grondin, Le tournant dans la pensée de Martin Heidegger (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1987) and F.-W von Herrmann, Wege ins Ereignis: Zu Heideggers Beiträge zur Philosophie (Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann, 1994).