Turkish troops muster on the Plain of Esdraelon in preparation for the attack on the Suez Canal. All Ottoman Army infantry divisions were permitted a military band. Under combat conditions the bandsmen performed duties as litter bearers and orderlies.

The assault on the town of Sarikamis, deep in the Caucasus Mountains, was the first major Ottoman offensive of the war, and sought to surround and annihilate the Russian forces present in the area. A further offensive aimed at severing the Suez Canal was launched, which sought to seriously damage the British Empire's commercial lifeline to its Eastern colonies. Both of these operations would end in failure.

As the Ottoman Empire tumbled towards war in autumn 1914, there were bitter disputes in Constantinople between Bronsart von Schellendorf and his Ottoman counterpart Hafiz Hakki Bey over the strategic direction of the coming conflict. The Ottomans had never foreseen a multi-front war against a combination of Great Powers and, especially, against their long-time friend Great Britain. Consequently, the concentration plan, which had been written the previous April for a war against Bulgaria, stripped away forces from Palestine and Mesopotamia and left the Caucasus devoid of reinforcements as well. In fact, the military deployment of the empire's armies did not align at all with the diplomatic situation as it developed. This situation vexed both men, who were aggressive professionals and, as both were trained general staff officers, recognized that wars are won by offensive action. Hafiz Hakki pushed for offensives in Caucasia, Palestine and even Persia while the Germans advocated an amphibious attack on the Russian Black Sea coastline.

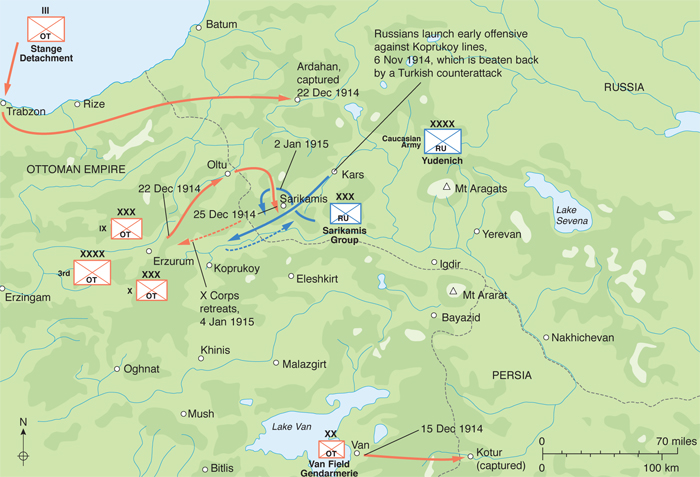

The Caucasus, November 1914–January 1915, including the Battle of Sarikamis. The Sarikamis encirclement was designed to create the conditions for an Ottoman version of Tannenberg and sought to annihilate the Russian Army.

In October, plans crystallized around offensives in the Caucasus and Palestine, and formal orders were sent to the respective armies. Liman von Sanders was offered command of the Ottoman Third Army, headquartered in the Anatolian city of Erzurum, but wisely declined. Although the Third Army and the Fourth Army in Palestine remained in the hands of Ottoman commanders, they had German chiefs of staff, Colonel Guse and Colonel von Frankenberg respectively, to coordinate and assist in planning. Although short of equipment, both armies were at full strength in manpower, much of which had combat experience in the recent Balkan Wars.

The first major Ottoman offensive of the war was aimed at the town of Sarikamis, deep in the Caucasus Mountains, and which in December 1914 was blanketed with snow and gripped by sub-zero temperatures. It was the brainchild of Enver Pasha, and contrary to the version of events in most histories, was not a massive effort designed to recover lands inhabited by fellow Turkish peoples. Moreover, to this day Enver's plan is almost universally seen as recklessly ill conceived and doomed from the start. On the contrary, it was, in fact, carefully crafted and modelled on the German victory in September over the Russians at Tannenberg (in East Prussia); German operational reports from the latter indicated that when Russian units were surrounded, command and control collapsed and surrender soon followed. Enver envisioned a single envelopment of the over-extended Russian Army along the Ottoman northeast frontier, and thought that cutting their lines of communications at Sarikamis would force a collapse and surrender.

Turkish troops muster in 1914. This is the famous ‘Constantinople Fire Brigade’, which performed ceremonial guard duties as well serving as the city's fire fighters. They are easily distinguished by their helmets.

The actual planning guidance for offensive operations was sent from the general staff to the Ottoman Third Army in early September, when it became apparent that war against the Entente Powers was more likely than war against Bulgaria and Greece. There were two schools of thought within the staff concerning how this should be done: the first, from Colonel Bronsart von Schellendorf, envisioned a limited-scope offensive with the forces at hand, while the second, from Colonel Hafiz Hakki Bey, foresaw a massive reinforcement of the Third Army, which would enable a large-scale offensive complete with an amphibious landing north of Batum on the Black Sea. For his part, General Liman von Sanders thought neither idea was sound, and advanced the idea that the Turks should maintain a defensive strategic posture. As autumn set in, the Tannenberg reports began to arrive and Enver sent Bronsart von Schellendorf and Hafiz Hakki Bey to Berlin in late October 1914 for strategic consultations. When they returned (after the outbreak of hostilities), planning for a Caucasian offensive resumed in earnest as all opposition to an offensive strategic posture was extinguished.

The Ottoman Army embraced the ‘German way of war’ as a result of the establishment of the German general staff system and German war academy curriculum. Part of this German legacy included campaign planning for battles of encirclement and annihilation. The German curriculum glorified Hannibal's battle at Cannae as the ultimate expression of the operational art, and the Schlieffen Plan would come to exemplify this concept. Over a period of several decades Ottoman commanders became wedded to this doctrine. In the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, Ottoman commanders consistently tried to encircle their enemies, notably at the battles of Kirkkilise, Kumanova, Bitola and Sarkoy. This doctrinal pattern of planning for encirclement operations continued into World War I, notably at Sarikamis, Kut al-Amara, the Caucasus in 1916 and First Gaza. Ottoman commanders failed in these ambitious attempts to execute the ne plus ultra of the military art. In 1922, however, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk would destroy the Greek Army in a dramatic battle of encirclement and annihilation known as the Great Offensive.

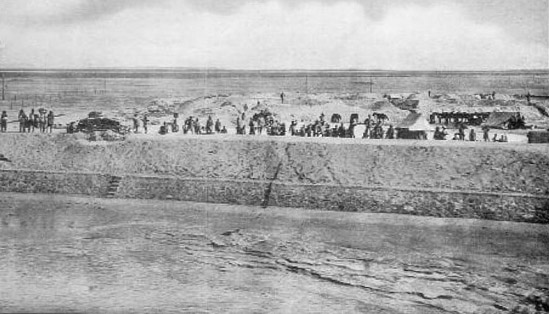

Russian troops in the trenches at Sarikamis. One of the lessons learned by the Russian Army in the Russo-Japanese War was to dig trenches quickly. A group of staff officers can be seen observing from the centre of the trench line.

On 8 November 1914, the Ottoman Navy cruiser Mecidiye brought Hafiz Hakki Bey to Trabzon on the Black Sea coast. His mission was to energize the offensive spirit of the Third Army, and he went directly to the headquarters at Erzurum. There Hafiz Hakki Bey delivered explicit guidance to the chief of staff, German Colonel Guse, to prepare an operational offensive against the Russians. Tannenberg was used as a model of how this might be accomplished, and Hafiz Hakki Bey hoped to use the oncoming winter weather for additional leverage against the Russians. He encountered immediate resistance from the commanders of the Third Army and the IX Corps, who opposed the ambitious plan. Enver summarily relieved the latter, and sent a message to the army by placing Hafiz Hakki Bey in command of the corps.

Planning now proceeded at an accelerated rate, and the Turks secretly massed six of their nine available divisions (which were organized into the IX and X corps) into a powerful attack force along the left flank of the Koprukoy lines. The attack force was to march northeast through Oltu and then pivot sharply to the southeast toward Sarikamis, which lay on the only paved road leading from the Russian supply base at Kars to the Russian frontline troops facing Koprukoy. Possession of the town of Sarikamis effectively cut off the Russians from their rear, isolating them in winter weather; if the Tannenberg paradigm held true, this would cause confusion and a collapse in morale.

The general staff was unable to send large reinforcements for the Third Army offensive due to time constraints and the distances involved, but it was able to send the 8th Infantry Regiment by sea to Trabzon as a limited reinforcement and to conduct a diversionary operation. This operation would shield the northern flank of the Third Army in the area south of Batum by advancing on the city of Ardahan, acting as a sort of matador's cloak to distract the Russians. To the south of the operational area, the Third Army thinned its lines to allow the concentration of effort, leaving mostly cavalry and gendarmes to watch the long southern front.

The Russian Caucasian Army had five infantry divisions, two Cossack divisions, and a handful of infantry brigades and cavalry regiments. Altogether in October 1914, it comprised about 100,000 infantry, 15,000 cavalry and 256 guns. The nominal commander was the regional viceroy, but the real work of planning and organizing the army lay in the hands of the chief of staff, General Yudenich. The Ottoman Third Army was slightly smaller with about 90,000 infantry and 250 guns. The Ottoman cavalry was organized into a regular cavalry division and four reserve cavalry divisions of irregulars, formerly known as the Hamidiye cavalry, whose value in combat was debatable. The Turks fielded 4000 regular cavalry and possibly as many as 10,000 tribal warriors. The Russians broke their army down into tactical groups, the largest of which, the Sarikamis Group, stood at the Koprukoy lines and was composed of about 65,000 infantry and 172 guns. For the attack the Turks massed 49,000 men in their enveloping wing and left 27,000 men, including their cavalry (which was of limited value in the rugged mountains northeast of Erzurum), on the line. This deployment gave the Turks a small numerical margin of superiority over the troops of the Sarikamis Group.

The attack began before dawn on 22 December in good weather. Together with his assistant chief of staff Bronsart von Schellendorf, Enver Pasha had made the long journey to Erzurum and was on hand to watch the troops cross the frontier. The infantry of X Corps conducted a remarkable foot march advancing 75km (46 miles) through the mountains at Oltu to reach Sarikamis on 25 December. However, as they progressed the weather turned colder. The adjacent IX Corps also came up, so that the Third Army had two corps in position to attack Sarikamis. But as they approached the city the Turks began to encounter resistance centred on the old town. Unlike the events of August in the dark forests of East Prussia, the Russians in Sarikamis fought hard for the town. Moreover, their command and control apparatus remained intact and they were able to take several regiments off the Koprukoy line and send them to reinforce the Sarikamis garrison. In spite of this, the Turks took most of the old town. Reacting to this, on 28 December the Ottoman X Corps seized blocking positions to the north along the Kars–Sarikamis road, aiming to further weaken Russian resolve. Enver now expected a rapid Russian collapse, but instead the aggressive General Yudenich kept his head and coolly orchestrated a counterattack using forces pulled off the line and fresh forces from Kars. Yudenich's effective actions now gave the Russians numerical superiority in the immediate vicinity of Sarikamis. To make matters worse, the weather turned against the outnumbered Turks, with temperatures dropping to minus 26 degrees centigrade; the Turks were unprepared and lacked winter kit, having expected a quick victory. The tempo of fighting slowed and the Russians used this time to plan an encirclement of their own.

Yudenich was, arguably, the most successful Russian commander of World War I. Born in 1862, Yudenich entered the Imperial Russian Army in 1879, graduating from the General Staff Academy eight years later, after which he served on the general staff until 1902. He served in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 as a regimental commander and rose rapidly to general officer rank. Yudenich was appointed chief of staff of Russian forces in the Caucasian area in 1913 (having served as deputy chief of staff from 1907). He was instrumental in inflicting a series of defeats on the Turks, including that at Sarikamis in December 1914. In the following year he turned back Ottoman offensives, and captured Erzurum in February 1916 and Erzincan in July. In March 1917 Yudenich was forced to discontinue active operations in the Caucasus because of the ongoing revolution. The Provisional Government forcibly retired him and Yudenich fled to Finland during the October Revolution. He became a commander in the White armies and marched on Petrograd in the autumn of 1919, but was forced back into Estonia where the armies were disbanded. Fleeing for the second time, Yudenich went into exile in France, and died there in 1933.

Turkish riflemen en route to war. The Ottoman Empire had very few railroads. Those that existed were built by foreign entrepreneurs and seldom ran to the combat fronts. Ottoman soldiers usually deployed to their areas on foot.

‘There was one road out of the Turnagel Woods that night and only the X Corps returned – the IX Corps did not return.’

Colonel Hafiz Hakki, Ottoman General Staff, 1915

On 2 January 1915, Yudenich unleashed a powerful counter-offensive that swiftly re-enveloped the Ottoman left wing around Sarikamis. Enver reacted by placing both Ottoman corps under a single commander – ironically, the general staff's strategic planner Hafiz Hakki Bey, who had argued for the Caucasian offensive earlier in the autumn. The battered Turks tried to form a perimeter, but the Russians turned it into a noose. By 4 January 1915, Hafiz Hakki Bey was forced to choose between losing his entire force or leaving a rearguard to die while the others escaped. In the end, he left IX Corps in the Turnagel Woods to the northwest of Sarikamis in order to buy time for X Corps to retreat. IX Corps’ three infantry divisions were destroyed and its commander Ali Insan Pasha was captured with his staff. The Turkish collapse and the subsequent rout lost them an entire army corps – a third of Ottoman Third Army's combat strength.

The Sarikamis campaign ranks as one of the greatest military disasters of the twentieth century. It was neither badly planned nor badly conceived, rather it came up against unexpected and brilliantly effective the Russian command and control in the form of General Yudenich. A humiliated Enver, who had come to the front to glory in his victory, crept back to Constantinople in early January 1915. Western estimates of 90,000 Turks killed are exaggerated, with the actual losses consisting of some 30,000 dead and 7000 taken prisoner. In scenes reminiscent of Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, many of the casualties froze to death or suffered serious frostbite. The shattered Ottoman Third Army returned to its defensive positions to begin rebuilding itself.

At the same time as the Sarikamis campaign, Ottoman military activity took place to the north and southeast. To occupy the Russians and divert their attention and reserves from the Sarikamis region, the Ottoman general staff sent an infantry regiment and artillery by ship to the Black Sea port of Trabzon. Command of the regiment (and some frontier forces) was given to German Major Stange, a Prussian artilleryman who had been assigned to the fortress at Erzurum; the entire force was named the Stange Detachment. Stange's mission was to advance and tie down the Russian Army near Batum. Instead, he attacked vigorously and seized the Russian town of Ardahan on 22 December 1914. There Stange found a number of loosely run, irregular bands of the Ottoman Special Organization (SO), who had been waging guerrilla warfare on the Russian Army and the local Armenian and Greek population. Stange's attack stalled, but together with the SO troops, he then held most of his ground through the winter.

Kressenstein (often called Kress von Kress, or von Kress) was a Bavarian artillery officer, and was assigned to the German Military Mission in January 1914. He was assigned to the Fourth Army in September as chief of staff. He planned the attack on the Suez Canal in January 1915. In March and April 1917 he planned the successful defence of Gaza during the Battles of Gaza and was awarded the Pour le Mérite. Kress's actions at Third Gaza in October 1917 led to the collapse of the Ottoman position and the loss of Jerusalem. He was given command of the Ottoman Eighth Army in defence of the coastal sector of the front until the summer of 1918, when he was transferred to command the German Military Mission in the Caucasus. He retired as a lieutenant-general in 1929.

Far to the southeast along the Ottoman–Persian frontier, Ottoman troops also attacked, in what is known as the First Invasion of Persia. This scheme was born of Enver's grand dreams of a pan-Turanian invasion, which would liberate and unite the Turkish peoples held in thrall by the Persians. While the Sarikamis operation is sometimes presented as a part of this scheme, it was, in fact, a separate and purely operational envelopment. However, the Persian invasion was the centrepiece of Enver's plan of pan-Turanic expansion. He hoped to invade Persia and then pivot northward into Azerbaijan, all the while raising rebellion among oppressed Turkic peoples. Unfortunately, the only force available for this ambitious undertaking was the Van Field Gendarmerie Division, a paramilitary force with few machine guns or artillery. Nevertheless, Enver ordered it forward and it crossed the frontier on 15 December to take the town of Kotur and a small corner of Persian territory. The local Turks failed to rally to the cause, and the poorly thought-out plan only served to provoke the Russians, who sent strong forces to occupy Tabriz and Tehran.

Recognizing that the ill equipped Gendarmerie would need reinforcement, Enver ordered the dispatch of two expeditionary forces from Constantinople to the distant front in Persia. These ad hoc units of divisional strength, under the command of lieutenant-colonels Kazim and Halil (Enver's uncle), began to depart by train on 11 December 1914. Enver's orders to them were to take Tabriz. However, the ageing and inefficient Ottoman transportation system failed to move them quickly, and by mid-January both expeditionary forces were only midway through Anatolia, where many of the men became infected with typhus. Finally, in mid-February 1915 they reached the front, but nowhere near the Persian frontier. In the aftermath of the Sarikamis disaster, the Ottoman general staff diverted them to the fortress city of Erzurum to shore up the battered Third Army. The unsupported Gendarmerie troops remained in Kotur until March 1915, when the Russians pushed them back to the frontier.

Also during the winter of 1914/15, the restive Armenian population began to stir under the agitation of the Armenian committees. The largest of these was the Armenian Revolutionary Federation or the Dashnaks, which had smuggled large quantities of arms and explosives into the six eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Encouraged and aided by the Russians, the Armenian leadership now believed that a window of opportunity for rebellion had opened, with the Ottoman Empire at war with three of the Great Powers. Over the winter, terrorist incidents by Armenians mounted, and a part of the Armenian population prepared for insurrection against the Turks. There were also six highly motivated Armenian regiments, composed of émigré Ottoman Armenian subjects, fighting with the Russian Army and a highly organized ‘fifth column’ of Armenians began to lay the groundwork for outright rebellion in Van Province.

With minor exceptions, at the strategic and operational level Ottoman military performance in the Caucasus was very poor, and the strategic posture of the Third Army in early 1915 was worse than it was when the war began. For the most part, the Turks, and especially Enver Pasha, tried to do too much with too little and their wildly optimistic plans failed against the Russians, who had better railways and more soldiers. However, the Ottoman Army proved that it possessed an offensive spirit, and a remarkable ability to mass forces quickly and march long distances in harsh terrain and climates – an aspect significantly unremarked upon in Western historiography. This capability, based on good training and solid discipline, would serve the Turks well in the coming years.

In September 1914, Bronsart von Schellendorf and Hafiz Hakki Bey clashed in a major dispute over the strategic direction of the Ottoman Empire's war plans. While they disagreed about plans for the Caucasus, they agreed that the removal of Ottoman forces from Palestine needed to be reversed because war against Great Britain was almost inevitable. By the end of the month they were also in agreement that the Turks should launch an offensive aimed at severing the Suez Canal. This was thought to be a viable strategic option, which would in turn seriously damage the British Empire's commercial lifeline to its Eastern colonies. A new Fourth Army was formed and Cemal Pasha, the navy minister, took command of it on 18 November 1914. Several Germans were sent to assist him, including Lieutenant-Colonel Friedrich Kress von Kressenstein. The first-class infantry divisions were also ordered south to form the nucleus of Cemal's army, including 8th Division from III Corps and 10th Division from Smyrna. These were well trained formations composed of Anatolian Turks. The 25th Division from Syria, an Arab unit that also contained a high percentage of ethnic Turks from the Syrian cities, was also sent south.

Guarding the banks of the Suez Canal. The threat of an Ottoman strike cutting the Suez Canal forced the British to station a large garrison in Egypt until 1916. The Royal Navy deployed ships in the canal as well for gunnery support.

The evolving plan owed much to Kress, the new chief of staff, who envisioned marching an entire army corps across the Sinai Desert from Palestine. Once in position, the corps would launch a daring coup de main seizure of Ismailia using an infantry division. This would cut the canal at its mid-point, which the Turks thought might negate the tremendous firepower of the Royal Navy's ships. Kress planned to deploy a second division across the canal as well, and to secure the flanks with two additional infantry divisions. The plan was risky, but the Turks hoped that success might incite the Muslim population of Egypt into a revolt against their British masters. To this end, the sultan was persuaded to declare a jihad against the enemy, and agents of the Teskelati Mahsusa (the Ottoman Special Organization, or SO) were sent on into Egypt to stir up and organize the Egyptians. The general staff began to move the divisions of the Ottoman VIII Corps into southern Palestine near Gaza in readiness for the attack. Enver wanted to launch the attack in early December 1914, but chronic problems with the railway intervened. Palestine was particularly affected by two uncompleted stretches in the Ottoman railway system, one at Pozanti in the Taurus Mountains and a second at Osmaniye in the Amanus Mountains. At each location everything had to be unloaded and brought by animals over the (respectively) 55km (34-mile) and 35km (21.8-mile) gaps, and then everything was reloaded aboard trains. This meant that supplies going to Palestine might take as long as 60 days to arrive at the front.

The Turkish assault on the Suez Canal, January–February 1915. The Turks hoped not only to cut British communications through the Suez Canal, but also to raise a jihad amongst the Egyptian population against the British.

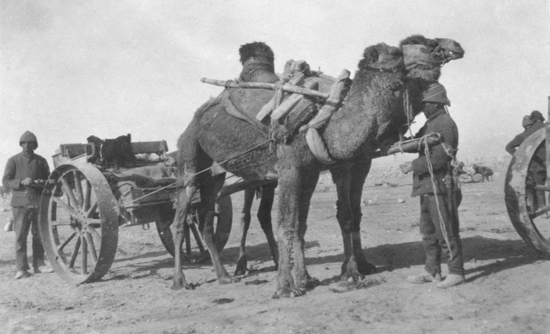

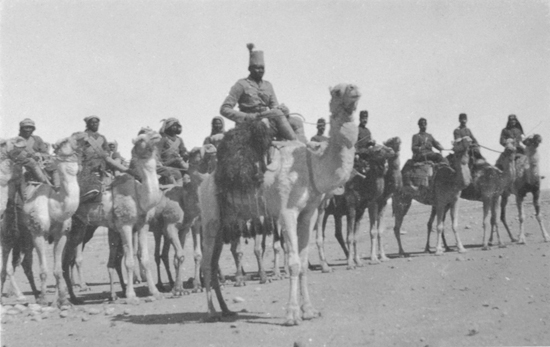

Logistics were thus a huge problem for the Turks, but their immediate tactical problem dealt with traversing the waterless Sinai Desert with an army of four divisions. In the end, they cut down their substantial force to a bare 13,000 men and eight artillery batteries, accompanied by about 1500 irregulars and Arabs, whom they planned to turn loose in Egypt to raise a revolt. Huge water tanks and storage depots were moved forward to support the troops, and for the actual movement through the desert the force used 1000 horses, 12,000 camels and 300 oxen. The oxen were needed to transport the heavy pontoons and boats necessary to cross the canal itself. The movement, organized into three tactical groups, began on 14 January 1915, and the Turks reached their assembly area on the last day of the month. It was a significant achievement and the British seemed unaware of the Ottoman presence on their doorstep. Morale in the Ottoman expeditionary force was high as it prepared to attack.

The pre-war British garrison in Egypt was small, merely a brigade, but in autumn 1914 two Indian Army infantry divisions were sent to Egypt as well as a territorial division from England. Although the British had abandoned the Sinai, Major-General Sir John Maxwell established a strong defensive line along the western bank of the canal. By December Maxwell had 30,000 troops defending the length of the canal and a division of the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) had arrived as well, for a total force that far outnumbered the Turks. Maxwell's army was a polyglot of territorial, Indian and colonial troops, but it was more than sufficient to defend Egypt. Importantly, the British enjoyed aerial reconnaissance and easily tracked the three major enemy groups across the desert; however, they remained uncertain as to the main objective. As the Turks neared the canal they began to move at night. Consequently, by 31 January 1915 the Turks lay in well concealed assembly areas about 10km (6 miles) east of Ismailia, leaving the British without a clear picture of exactly where the main body was located.

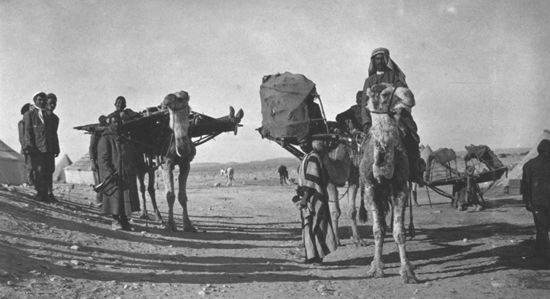

Turkish troops depart for the Suez Canal in late 1914. The first Ottoman offensive against the Suez canal in early 1915 failed. However, it highlighted the remarkable ability of the Turks to overcome geographic obstacles and the climate.

Turkish troops make use of camel transport in the desert. Throughout the war the Turks remained reliant on animal transport to sustain their armies. Some 210,000 animals were mobilized in 1914 to support the Ottoman war effort.

On the night of 2 February 1915, infantry of the 25th Division moved forward into assault positions on the eastern bank of the canal. There the division joined an assault force of two infantry battalions together with the pontoons and boats that the Ottoman engineers had laboriously brought across the desert. The flanking units prepared to conduct diversionary attacks, and eight batteries of light artillery were brought forward as well. However, as they loaded their boats and entered the water the Ottoman infantry were observed by the enemy, and although they actually achieved local surprise, a small British observation post opened fire almost immediately. This greatly disturbed the crossing troops, who had had very little practice in actual amphibious operations. Many panicked under fire and jumped out of the boats, but about two companies of infantry made it to the far side. They secured a tiny bridgehead and began to dig in. The Turks supported their men with artillery fire and brought up another division to reinforce the crossing, but effective gunfire from Royal Navy ships in the canal made this impossible. In the meantime, the well orchestrated British defenders brought up an Indian Army counterattack force, which launched assaults throughout the following day. As the strength of the British force became apparent, Cemal ordered the abandonment of the attack at 4pm on 3 February. He was unable, however, to bring back his assault force, and most of his soldiers on the west bank were captured or killed as the main body withdrew into the desert. All the pontoons and boats, which had so laboriously been transported across the Sinai, were abandoned. Casualties were light on both sides. Many of the Ottoman troops involved in the crossing operation were ethnic Arabs, and some surrendered with little resistance. The ill conceived plan for a pan-Islamic insurrection in Egypt met with little enthusiasm, and many of the agents were rounded up.

The offensive ended as rapidly as it began, as Cemal moved his forces back to the Gaza–Beersheba line. For their part, the British were content to let the Turks withdraw unchallenged, largely because they had few units trained in pursuit operations as well as an immediate lack of camels to carry water. The British were cheered by this victory, which appeared to confirm their experience in Mesopotamia that the Turks were, indeed, a sad excuse for a modern army.

In Mesopotamia the Ottoman strategic situation was rapidly unravelling, as the ill equipped 38th Infantry Division, which had been employed in piecemeal fashion, was destroyed by the advancing Indian Army. To restore the situation, Enver sent a famous irregular commander from the Ottoman Special Organization named Suleyman Askeri, and also reversed the deployment of the 35th Infantry Division, which had left Mesopotamia earlier for the Caucasus. Suleyman Askeri set up one division at Nasiriya on the Euphrates River and his other division on the Tigris River, and set them to digging in. He also reinforced the 38th Division with new levies, thus restoring some measure of combat capability. While the Turks remained weak, Suleyman Askeri's efforts restored coherent direction to the theatre. This brought the British to a halt as they waited for reinforcements.

The Ottoman Army at this time was also engaged in two other minor, but active, theatres of war. The larger of these involved a counter-insurgency campaign against rebellious Arab tribes in the Hedjaz along the pilgrimage railroad to Mecca and against rebellious tribes in Yemen. These campaigns tied up an entire army corps of four infantry divisions, but, while irritating, were not a great strain on the Ottoman war effort. There was also a tiny campaign of insurgency supporting the Sanussi tribesmen against the Italians in Libya, which was extended into British-controlled Egypt. In a sort of Lawrence of Arabia scheme in reverse, Ottoman officers carrying gold and arms were sent (most often by submarine or coastal tramp steamers) into the interior to assist the tribesmen. The targets of their raids and sorties were the coast road and isolated outposts. This effort was heavily publicized in the Islamic world, but added almost nothing to the war effort.

Kankalah’ stretchers on camels bringing wounded out of the Suez Canal area. Ottoman medical services were primitive by Western standards. Over 450,000 Ottoman soldiers died of diseases alone during the war.

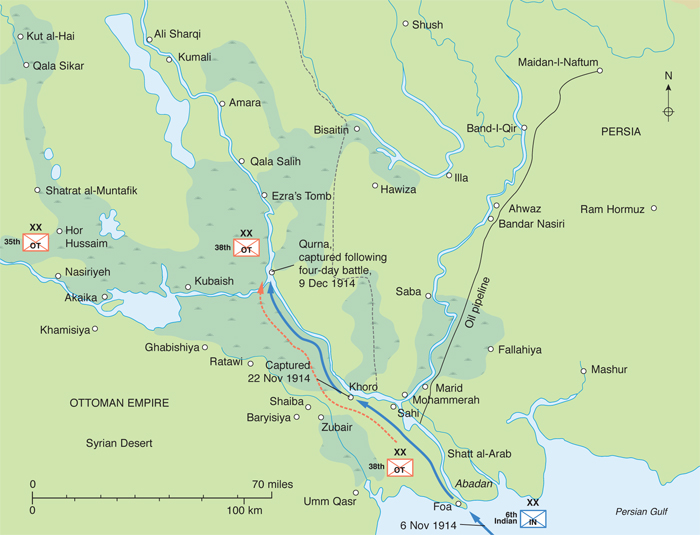

Lower Mesopotamia, November–December 1914. The occupation of Abadan and the push up the Shatt al-Arab was deceptively easy. The lure of Baghdad proved irresistible to British commanders.

The initial campaigns against the Turks were apparently hugely successful at low cost to the Allies. The Turkish actions at Sarikamis, in particular, were seen as amateurish and doomed from the start, and the failed Suez Canal operation appeared as a minor, clumsy version of it. Compounding this picture was the successful occupation of lower Mesopotamia; moreover, Royal Navy raids near Alexandretta over the winter found a population that appeared to be apathetic to the war effort. Famously, Ottoman officials hosted the landing parties from HMS Doris and actually helped the Royal Navy sailors blow up strategic railway bridges! The war against the Turks had almost a comic opera atmosphere and their army appeared inept.

All of this was seen by eager Allied leaders and planners as evidence that the ‘sick man of Europe’ was about to collapse. Easy victories over small portions of the Ottoman Army or over poorly trained troops was also seen as proof that pre-war observations concerning the low capability of the Turks were correct. In fact, none of this was at all true. The Sarikamis campaign failed because of faulty assumptions about Russian command and control. In that campaign the Turks secretly massed two-thirds of the Ottoman Third Army's combat strength and launched it over snow-covered mountains to seize objectives 75km (46 miles) distant, almost succeeding in doing so. In Palestine, the Ottoman Fourth Army moved a large force rapidly across a waterless desert and mounted an amphibious assault crossing of a major water obstacle. In both cases, the Turks displayed considerable staff proficiency in planning complex operations in harsh climates and difficult terrain. Moreover, Ottoman soldiers proved resilient and showed high levels of mobility and march discipline. The fact that the Turks were aggressive and possessed these kinds of strengths was lost on the Allies. Defeat disguised the real capability of the Ottoman Army.

The poor showing in Mesopotamia showed the Turks in the worst light of all, because there, many of the conscripts were untrained Arab tribesmen, who vanished at the first shots. In truth, the cream of the Ottoman Army, its best leaders and its best fighting formations had been sent to Thrace, where they idled waiting for a Bulgarian attack that never came. In particular, the best-trained and finest fighting formation in the army, the Ottoman III Corps, garrisoned the Gallipoli Peninsula, where it fortified its positions and prepared for war.

This misappraisal of the Ottoman Army was the product of European ethnocentrism and a result of Social Darwinism, which cast the Turks as uneducated peasants incapable of competing on even terms with Europeans. Ottoman performance in the first months of the war exaggerated these ideas, and appeared to confirm European notions. Even the Turks’ German allies tended to think of them in terms of their weaknesses rather than their strengths. The British, in particular, badly underestimated their Ottoman adversary, which would haunt them in the coming year in their clashes with the Ottomans at Gallipoli and in the siege of Kut al-Amara.

Sudanese deserters serving as Ottoman guides. The Ottoman invasion force included contingents of Sinai Bedouins, Druses, Syrian Circassians, and Sanussi refugees from Libya.