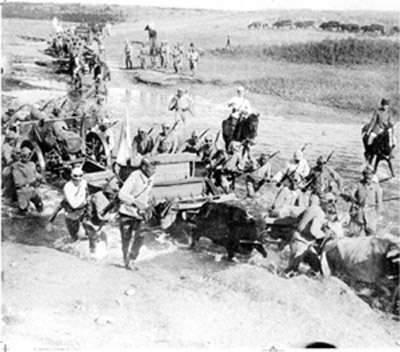

A Bavarian artillery unit at Kut al-Amara. Most German troops sent to the Ottoman Empire served in Palestine, the Sinai and Syria. However, some specialized units, such as artillery and air detachments, reached the outer theatres.

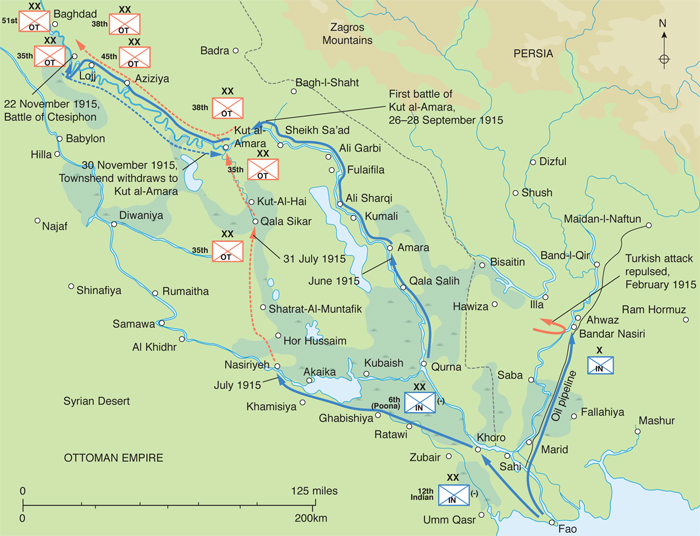

In early 1915, skirmishing took place between the Turks and the Indian Army in Mesopotamia. The Turks began an operation to force Allied troops from the area, leading to General Charles Townshend's counteroperations. Despite a resounding victory at the First Battle of Kut, Townshend's force became encircled and was forced to surrender. Fighting would continue in the theatre until late 1918.

In February and March 1915, there were several small engagements between the Turks and the Indian Army in Mesopotamia, but each was too weak to secure decisive victory. Alarmed by the seemingly effortless seizure of the lower Tigris and Euphrates basin by the Indian Army, the Turks began to contemplate offensive operations designed to push them back down river. The Turkish area commander, Suleyman Askeri, decided to conduct a flanking attack on the British positions at Basra. In doing so, he hoped to avoid the main British positions at Qurna, and achieve local numerical superiority. A British cavalry brigade held the town of Shaiba – the key to the southern approach to the city. Suleyman Askeri began moving in early April 1915, but was detected by the British, who used their time to strengthen their defences. On the morning of 12 April the Turks attacked the fortified camp at Shaiba with a brief artillery bombardment from 12 field guns. Turkish infantry attacked shortly thereafter, but failed, and further attacks continued all day and the next as well. Suleyman Askeri called off his attacks when a British cavalry counterattack threatened his flanks. He lost a third of the 4000 men he started with, and was unable to prevent the remainder from fleeing north.

Major George Godfrey Wheeler, VC, of the 7th Hariana Lancers leads his squadron in an attempt to capture a Turkish flag at Shaiba, Mesopotamia, 13 April 1915. In the early campaigns in Mesopotamia the British and Indians faced second-rate and poorly equipped Ottoman forces, and their easy victories drew them up river towards Baghdad.

The British immediately advanced on the Turkish positions. They took the first line of Turkish trenches as many Arabs, who were drafted involuntarily into the Ottoman Army, surrendered en masse, but they failed to break through Suleyman’s lines. Over a three-day period, the Turks suffered 6000 men killed or wounded, including 2000 Arab tribesmen, and lost over 700 prisoners, forcing them to withdraw to Khamisiya, 144km (89 miles) up river. There the unfortunate Suleyman Askeri, who had been wounded earlier in the campaign and was now semi-invalided on his camp bed, assembled his staff. He was something of a legend in the Ottoman Army and was a renowned guerrilla leader. Depressed by his defeat, he shot himself to avoid further humiliation. The official Turkish campaign history mentions his suicide, but it is not explained in great detail. It notes that he was concerned about the discipline and fighting spirit of his Arab levies as well as the high percentage of these men in his infantry regiment. It was a bleak day for the Turks, and interim command in Mesopotamia fell to Mehmed Fazil Pasha.

However, the Turkish forces in Mesopotamia were about to receive an injection of reinforcements that would restore their strength, as the general staff began to return forces to the region, such as the 35th Division. Although the latter was incomplete at that point, it would gain strength throughout the remainder of 1915.

Largely due to their unexpected success in Mesopotamia, the India Office and the Indian Army’s general staff decided in late April 1915 to continue the advance up river to the port of Amara on the Euphrates and to Nasiriya on the Tigris. General Charles V.F. Townshend arrived in Qurna to command the small British army. Once there, and seeing the effects of the seasonal flooding, Townshend determined to make a single advance up the Tigris with his small force, and soon Amara was captured. The Turks contested the advance with a small fleet of armed river steamers. In June, after the seasonal flooding had ended, Townshend took Nasiriya as well. The Indian Army’s 12th Division arrived to reinforce the expedition, but (save one brigade) Townshend was forced to employ it along the river to assist in bringing supplies forward. The political repercussions from the already failing Gallipoli campaign meant the British War Office and the India Office now began to view the successes in Mesopotamia with interest. Although aware of how short of soldiers Townshend was, London began to push for further advances towards Baghdad itself. With strong Ottoman forces entrenched on the Euphrates, Townshend began to make preparations for moving up the Tigris on the town of Kut al-Amara. Facing him at Kut al-Amara were the remnants of the 38th Division, a poorly armed group of about five infantry battalions.

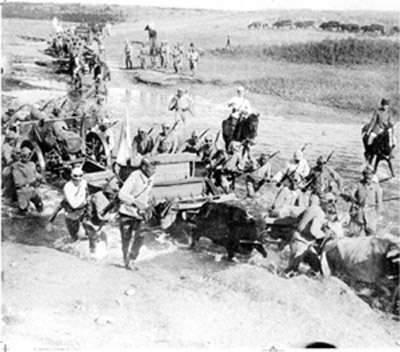

Corporal Trice of the 6th Ammunition Column, Royal Field Artillery lands a machine gun from a barge under enemy fire near Nassiriyah, Mesopotamia, on 24 July 1915. Trice was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions. In the absence of railways in Mesopotamia, the Tigris River became an important British transportation artery. However, the meandering of the river tripled the distance British forces had to cover moving between Basra and Baghdad.

The weak Ottoman position in Mesopotamia quickly changed for the better when a new and aggressive commander, Nurettin Pasha (or Nur ud Din Pasha in the British histories), arrived to re-energize the defence. Moreover, well trained reinforcements were slowly finding their way to Mesopotamia. In November 1915, the 45th Division began to arrive and the 51st Division, formed in Constantinople in the late autumn of 1914 from First Army assets as an expeditionary force, was ordered to Mesopotamia from the Caucasus. Its sister, the 52nd Division, would shortly follow. In Baghdad, Nurettin augmented the 45th Division with 5000 Gendarmes and frontier guards, bringing it up to full strength. However, these forces would not be combat ready for months, and in the meantime, Nurettin had to rely on the 35th Division and the remnants of the 38th Division, both of which comprised fewer than 4000 infantry. Nurettin had a total effective strength of about 7000 men, supported by a tiny amount of cavalry and artillery, available to deal with the renewed British attack.

An illustration commemorating the alliance of the Central Powers, although only the Ottoman crescent is shown. Cooperation between the Turks and Germans was excellent throughout the war. German staff officers and technicians provided great assistance to the Ottoman Empire, especially in logistics, transportation and communications.

As the autumn campaigning season of mild and dry weather set in, Townshend began his move on 1 September 1915. By 26 September, he was closing on the river port of Kut al-Amara. As the Turks were unsure where he would strike, they positioned the 35th Division on the right bank of the river and the 38th Division on the left. There was a small reserve of four battalions and some cavalry, mostly comprising locally drafted Arabs, whose morale was not high, and the Turks had a total of 38 artillery pieces. Townshend’s army moved closer in a night march and attacked the Ottoman lines early in the morning of 28 September 1915. By midday, Townshend had broken the Ottoman lines and, moreover, outflanked them in the north. Nurettin committed his tiny reserve, which was defeated, and by nightfall, his army was in retreat. Townshend pursued him, and by 5 October reached Aziziya. Townshend’s campaign had been extremely successful for little cost, while Nurettin lost about 4000 men and a third of his guns. The First Battle of Kut was a resounding British victory.

The relentless British advance reached Lajj on 21 October 1915. Three days later Townshend was directed to move on Baghdad by 14 November. He was uneasy about this: he had only a single reinforced Indian Army division, and intelligence had informed him that Turkish reinforcements were on the way. In public, however, Townshend exuded confidence. In truth, he had done well thus far and had reason to be optimistic. By early November, Townshend’s force, now numbering about 11,000 infantry, reached Ctesiphon (or Selman Pak as it was known to the Turks), which was only about 32km (20 miles) south of Baghdad. It was here that Nurettin chose to make his stand. The ensuing battle would mark the highwater point of the first British offensive in Mesopotamia.

Charles Townshend was the product of the late Victorian British Army and he was schooled in the small wars of the era. He was ambitious, restless and had a somewhat theatrical personality. His successful defence of Chitral Fort in 1895 during a 50-day siege had already won him fame at home. He served against the Mahdi in Sudan and briefly in the Second Boer War. After service in Paris as an attaché, where he became enamoured with French methods, he was posted to Rawal Pindi in command of the 6th (Poona) Division. Typical of his times, he was dismissive of the capability and fighting spirit of the Ottoman Army, and his campaign thus far vindicated these beliefs. His division was a regular Indian Army one of three brigades, each of three Indian battalions and one British battalion. It was largely untrained in modern conventional operations and had little artillery and few machine guns. There were almost no replacements available when it took casualties, particularly among the officers. Townshend also had the 30th Brigade, the 6th Cavalry Brigade and a flotilla of river gunboats. At Ctesiphon, the meandering river had taken Townshend some 800km (500 miles) from the sea.

Townshend was originally commissioned into the Royal Marine Light Infantry, but transferred to the Army. He served in the Sudan and Egypt and won a CB for his defence of Chitral Fort in 1895. To this he added the DSO for his role in Kitchener’s expedition against the Mahdi in 1898. With the British declaration of war Townshend was appointed to command the 6th (Poona) Indian Division in April 1915. He won several victories, but after defeat at Ctesiphon, he was isolated in al-Amara. He surrendered in April 1916 and his soldiers went into a harsh captivity. Townshend assisted with the negotiation of the Ottoman armistice at Mudros in October 1918, but his reputation continued to suffer as news of the maltreatment of his force spread. He died in 1924.

Ctesiphon Arch, Iraq. The ancient arch was visible from much of the battlefield at Ctesiphon (Selman Pak). It provided a colourful ancient backdrop for the modern battle fought there in 1915.

Nurettin was the Ottoman Army’s counterpart to Townshend. He had a conventional background and had fought guerrillas in Macedonia, the Greeks in 1897, and in the counter-insurgency campaign in Yemen. In 1914 he assumed command of an infantry division. While intelligent (he spoke four foreign languages), like Townshend he was not a graduate of a staff college or a war academy and had no strong political connections, having risen by ability. Unlike Townshend, he would end his career in command of an army, in the Turkish War of Independence.

While Townshend’s army was decreasing in strength each mile it advanced, Nurettin’s army grew stronger daily. Over the autumn, the Ottoman 45th Division completed deployment and joined the line. The well trained and combat-seasoned 51st Division (formerly called the 1st Expeditionary Force) arrived on 17 November, with seven fresh infantry battalions and a group of Schneider howitzers. One regiment of the 52nd Division had also arrived at Mosul and the remainder of the division was due shortly. Like its sister division, the 52nd (formerly called the 5th Expeditionary Force) was composed of combat veterans, whose morale and fighting capability was high. Nurettin now had a total effective strength of 20,000 men, armed with 19 machine guns and 52 cannon. He also had a small but capable cavalry force of about 400 men. More importantly, the 45th, 51st and 52nd divisions were some of the best fighting units in the army.

Nurettin selected a defensive position at Ctesiphon, where his right flank rested securely on the Tigris River. On 28 September he began to build two defensive lines in depth. The first line was about 10km (six miles) in length with extremely deep trenches, and had 12–15 earthwork redoubts, which were fronted with barbed wire and had overhead cover. The 38th and 45th divisions garrisoned this formidable line. Three kilometres to its rear lay the second Turkish defensive line, which was also strongly constructed. The 51st Division lay in reserve behind this line, and on the left flank of his entrenchments Nurettin positioned his cavalry. On the south side of the river, the 35th Division held similar positions. Although well dug in and possessing a large number of troops, Nurettin was far from confident. He was especially worried about the small number of guns available, as well as shortages of artillery shells. Consequently, he coordinated very detailed and centralized fire plans to maximize his combat power.

Turkish prisoners in Mesopotamia. Many of the prisoners taken early on by the British in Mesopotamia were locally conscripted men of Arab ethnicity. They were inadequately trained, and many favoured independence.

Townshend organized his force into four columns, one of which was a flying one to outflank the end of Nurettin’s line. Townshend knew that he was now outnumbered, but relied on the demonstrated propensity of the enemy to break at the critical moment. He had no idea of the calibre of reinforcements that Nurettin had received in the form of the 45th and 51st divisions. Townshend’s plan massed 9000 Indian and British soldiers against about 3000 Turks at the apex of the L-shaped Turkish line. Although outnumbered overall, Townshend achieved a decisive superiority at the point of his attack, which was on Redoubt 11, or the ‘Vital Point’ (VP) as Townshend called it.

At 6.30am on the bitterly cold morning of 22 November, the columns of the 6th (Poona) Division began their advance on the Turkish lines at Ctesiphon under the cover of artillery and naval gunfire. The British thought they had achieved surprise and that the Turks were fleeing the lines. Nothing could have been further from the truth as Turkish artillery, machine guns and rifles opened fire by the thousand on the attacking forces. Townshend continued to press the attack all morning, despite mounting losses, which now began to include a number of officers. At 11.30am, he ordered his cavalry brigade to attempt to outflank the Turks, but was met by the Turkish cavalry and the 51st Division. Nevertheless, by noon Townshend’s men controlled the first line of Turkish trenches and by 1.30pm they held some of the redoubts. Nurettin’s 38th and 45th divisions were shattered in this fight. Townshend himself went to the ‘vital point’ and stood for hours under withering enemy fire, demanding that his brigadiers do the same, which they did.

Nurettin Pasha (1873–1932)

Nurettin (Nur ud Din) Pasha was one of the few Ottoman officers to achieve high command without benefit of a staff college education. He was exceptionally talented and spoke Arabic, French, German and Russian. Nurettin served in the Ottoman–Greek War (1897) and fought guerrillas in both Macedonia (1902) and Yemen (1911–12). He commanded at regimental and divisional level. Selected to command the faltering Ottoman forces in Mesopotamia, he solidified the defences and saved the Ottoman strategic situation there by stopping the British at Ctesiphon. It was Nurettin’s campaign plan and vigorous pursuit of Townshend that sealed the fate of the 6th (Poona) Division and enabled the ultimate Ottoman victory. Although relieved by Enver’s uncle, Halil Pasha, Nurettin went on to successfully command Ottoman Army corps in 1917–18. Later, in the War of Independence, Nurettin commanded the First Army and played a key role in the expulsion of the Greeks from Asia Minor in 1922. He retired as a lieutenant-general in 1925.

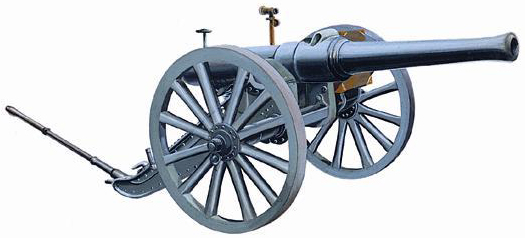

A 2.75in Mountain Gun of the Indian Army. The Indian Army divisions sent to Mesopotamia had almost no organic artillery, save a few mountain batteries. This was a result of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 after which the Indian Army had been stripped of its artillery.

At this point in the battle, Nurettin ordered the 51st Division under Cevid Bey to counterattack, bringing most of the 35th Division across the river to support it. The fighting continued all afternoon, and as darkness fell the British and Indian advance stalled. Townshend had lost a third of his officers engaged, and 4200 men out of 11,000. His field hospitals, equipped to handle 400 wounded, had to accommodate ten times that number. Nurettin estimated that he had lost some 6100 men, or 30 per cent of his army. That evening both the Turkish and the British commanders were profoundly depressed.

The next day fighting resumed, with Townshend attempting to continue his breakthrough and ordering a second cavalry flanking attack. That morning, a fierce sandstorm blew up, which badly affected the visibility of both armies. The battle continued and Nurettin committed the reformed remnants of the 38th and 45th divisions to a counterattack. Darkness halted the fighting, as both sides sank into exhausted inactivity. A discouraged Townshend began to evacuate his wounded. By 25 November the fighting had ended, and although he still held the first line of Turkish trenches, Townshend knew he could not break through. At midday he decided to withdraw. Simultaneously, Nurettin decided that he too had lost the battle and made preparations to withdraw to the Diyala River. Fortunately for the Turks, his cavalry detected the British retreat and Nurettin was able to reverse his order. The British threat to Baghdad in 1915 was over. Townshend was expected to attack, and his plan was a bold one that maximized the available resources. Given a less capable enemy commander, it might have worked.

Townshend withdrew his battered force down river to Aziziya. As he did so, Nurettin immediately sent the experienced 51st Division and his tribal cavalry brigade on a pursuit operation aimed at encircling and annihilating Townshend’s army. The latter had a narrow escape and was brought into camp at Umm at Tubul, where again it was almost encircled. On 1 December Nurettin again outflanked Townshend, forcing him to abandon 500 wounded men, who could not be evacuated in time. With the Turks following close on his heels and having been stung badly, Townshend pulled back to Shadi. There he made the fatal decision to bring his battered army into the dubious refuge of Kut al-Amara. Most of his force arrived there on 3 December.

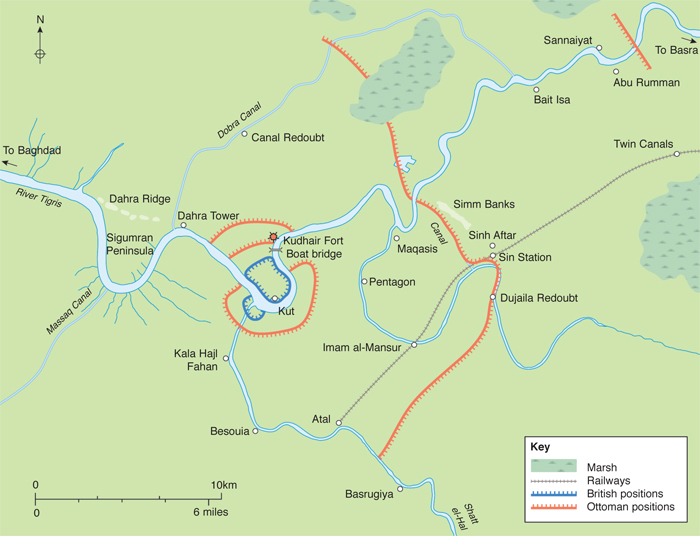

The town of Kut al-Amara lay in the bend of the Tigris River and contained a total of 7000 Arab residents. General Nixon, the overall British commander in Mesopotamia, approved Townshend’s decision, but the general staff had misgivings. From Townshend’s perspective, Kut al-Amara offered his army a protected enclave to rest his exhausted army and treat his wounded. Moreover, there were plentiful stores there and he began to fortify the town and offload his supplies from the river steamers. Overall, Townshend’s retreat was well handled and skilfully executed. His decision was certainly affected by his own personal experience in defending Chitral Fort and, probably, by his knowledge of the British tradition of successfully enduring sieges that included Lucknow, Rorke’s Drift, Ladysmith, Mafeking and Peking. Moreover, it could be argued that the British had a unique history, in most cases, of relieving encircled forces, Isandhlwana and Gordon’s last stand at Khartoum notwithstanding.

Townshend’s advance to Ctesiphon. The initial British offensive against Baghdad enjoyed dramatic success, which was unusual in the first year of the war. However, when first-line Ottoman troops arrived in theatre, the scales tipped against the British.

On 6 December Townshend sent his cavalry and some of the residents down stream, leaving him with about 11,600 combatants and 3350 non-combatants in the town. He had 60 days of full rations available, along with plenty of ammunition. He also had a powerful flotilla of river gunboats and steamers on the Tigris, and he knew that several additional Indian infantry divisions were arriving at Basra. Therefore, on this day, he was not alarmed about the possibility of being besieged in Kut al-Amara.

Nurettin, in the meantime, began his encirclement of the town by sending a mixed force south of the river and his cavalry east; these forces were to meet 20km (12 miles) down river. He sent the 45th Division to bottle up Townshend, and by the end of 6 December the Turks had completed the encirclement. The next day, he sent the 35th and 38th divisions down river to begin entrenching a defensive line against any relief force. Nurettin had created classic lines of contravallation (facing inward) and circumvallation (facing outward), which were first used by Julius Caesar to besiege Vercingetorix at Alesia in 52 BC. He knew that it was as important to stop the relief force as it was to isolate Townshend, and this act critically shaped the coming campaign. Kut al-Amara was now cut off from Basra, and the Turks began to dig a series of entrenchments across the neck of the bend in the Tigris where the town lay (there was a smaller British enclave across from the town on the southern bank).

A canvas cloth has turned a hole in the ground into a water supply point for British troops. Large quantities of fresh water were required in climates like Mesopotamia, and moving and storing it became highly important.

Nurettin hypothesized that Townshend had not yet had time to dig in, and so on 10 December he launched an hasty attack on the Old Fort and on a small bridgehead (called Woolpress Village) that the British held on the south bank of the river. However, Nurettin’s men were exhausted from their vigorous pursuit, and the no man’s land was entirely barren and flat; as a result, these attacks failed. Of equal importance, the Turks had only 50 guns and little artillery ammunition, and so could only conduct a brief bombardment.

On 12 December 1915 the German Field Marshal Colmar von der Goltz arrived at Kut al-Amara to take command in Mesopotamia. Contrary to general opinion, he did not replace Nurettin as army commander but took over as theatre commander. Goltz briefly observed the siege, but left for Baghdad within the week to inspect his forces preparing to invade Persia, which was where his real interests lay. By 23 December, about 25,000 Turkish soldiers ringed the town of Kut al-Amara. Nurettin, irritated by inactivity, launched another attack at night on the town on 24 December, which became known as the ‘Christmas Eve attack’. It was characterized by hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets, and was resolved in Townshend’s favour by the heroic efforts of the Oxford battalion. The Turks were repulsed with over 2000 casualties. At the end of December minor attacks by the 35th and 52nd divisions met a similar fate.

The Mesopotamian theatre became a deathtrap for many wounded soldiers, such as these injured British troops. Many who died there might have survived under less arduous conditions.

Despite this, the new year offered positive prospects for the Turks in Mesopotamia. General Townshend was bottled up in Kut al-Amara, and although the British were assembling a relief force at Basra, the 52nd Division had arrived in force. Importantly, the arrival of these divisions shifted the ethnic composition of Nurettin’s army from predominately Arabic to predominately Anatolian Turkish, shifting the balance of power in favour of the Turks in the defensive battles ahead. Also, the presence of the 72-year-old but still vigorous Goltz, whose experience with the Turks extended back into the 1880s, gave much inspiration to the Turks. Despite these bright prospects, the Ottoman Empire was unable to provide a steady flow of replacements and the 38th Division was disbanded in late December 1915.

The Turkish and German commander in Mesopotamia, 1916. Very few Germans served in Mesopotamia. The theatre was more or less a strategic backwater for both sides until the very end of the war.

The imposing British relief force poised to relieve Kut was led by Lieutenant-General Sir F.J. Aylmer. It was composed of the newly designated Tigris Corps (formerly the Indian Corps), comprising the veteran 3rd (Lahore) and 7th (Meerut) divisions, fresh from the Western Front. In France it had made important contributions to the ‘Race to the Sea’ and the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, but its overall performance was characterized as ‘undistinguished’. Like Townshend’s Indian division, the 3rd and 7th Divisions suffered from inadequate modern combined-arms training as well as from a lack of artillery and machine guns. They also suffered badly from a shortage of trained officers and NCOs to replace those lost in France. Unfortunately, these divisions displayed considerable contempt for the Turks, whom they considered as a second-class opponent. The arrival of the Tigris Corps returned the theatre to a relative balance of forces, as the four 12-battalion Indian divisions had 48 infantry battalions while the five nine-battalion Turkish divisions had 45 infantry battalions. Both sides were logistically challenged and, compared to the situation in France, woefully short of artillery (especially howitzers).

Goltz redesignated Nurettin’s Sixth Army as the Iraq Group on 21 December 1915. He did not change Nurettin’s order of battle, which divided his army into two parts: XVIII Corps (45th and 51st divisions) encircling Kut, and XIII Corps (35th and 52nd divisions) blocking the British relief force about 30km (18.6 miles) down stream. Oddly enough, there was both river and telegraph traffic between the encircled Townshend and the relief force.

In early January, the British began to probe the Turkish lines and to extend their cavalry around both flanks of the Turkish position. These probes were repulsed, but the British launched a stronger attack on 8 January 1916, which also failed. Nurettin brought his cavalry forward and continued to dig in. On 12 January Aylmer tried to break through the lines of the 52nd Division in a night attack, but his leading brigade was discovered by the alert Turks and was badly mauled. Strong British attacks continued to hammer the 52nd Division from 21 January; the Turks were helped by geography, which rested their right on the river and their left by a salt marsh, thus prohibiting movement. The Ottoman lines were well prepared, which did not deter the British from conducting repeated and costly frontal assaults. Casualties were so lop-sided that Aylmer was discouraged from further attacks along the Wadi-Nakhailat and halted his assaults. In Kut al-Amara, Townshend was astonished when news of Aylmer’s decision reached him.

The siege of Kut al-Amara. Nurettin created ‘lines of contravallation’ encircling Kut and ‘lines of circumvallation’ to thwart any relieving forces. Caesar had used these tactics successfully against Vercingetorix at Alesia in 52 BC.

Despite his successes, Nurettin would soon be replaced for political reasons. As it became apparent that the empire was about to win a major victory, Enver Pasha decided to replace him with his uncle, Colonel Halil Bey, who was then in command of XVIII Corps (it should be mentioned that Halil was a very capable soldier and had a distinguished combat record). Technically, Goltz remained in command of the entire Mesopotamian and Persian theatres, but he left the daily decision making to his Turkish commanders. The change of command occurred on 20 January, but Halil Bey wisely did not change Nurettin’s plans. Fleeing Arabs provided information about the deteriorating condition of the beleaguered British and Indian troops in Kut al-Amara, and Halil Bey decided to starve them out. In the meantime, Halil’s gunners lobbed shells into the town, which served to keep everyone inside the British lines on edge. Halil also repeatedly feigned attacks, which further exhausted the British, who were forced to respond as if these were real. In February, Townshend’s men went on half rations, while the Ottoman 2nd Division arrived as a reinforcement. Conditions inside the town of Kut al-Amara worsened throughout March. The Turks maintained a more or less continuous artillery bombardment and raided the town with aircraft on a frequent basis.

Aylmer made a single relief attempt on 8 March from the south bank of the Tigris River. Unfortunately, the newly arrived 2nd Division and the 35th Division had established a very strong defensive line about 10km (six miles) east of Kut al-Amara, which was backed by artillery and a strong reserve in each Turkish infantry division sector. By this time, the Kut al-Amara garrison was so weak that Halil was able to bring the 51st Division to reinforce the line. When the British attacks failed, the Turks vigorously counterattacked on 11 March; however, they only managed to achieve small gains.

April brought the final four attempts to relieve Townshend. On 5 and 6 April the British attacked the 51st Division, which had constructed a solid defensive line including minefields. It repelled the attacks, but withdrew to a fall-back position three kilometres (1.86 miles) to the rear. Another major attack followed on 9 April, but this too failed. Aylmer sent a large three-division offensive against XVIII Corps holding the south bank of the Tigris on 17/18 April, and a final push came four days later, which was also unsuccessful. None of these attacks gained ground, while the Turkish counterattacks punished the British severely. As the Turks were solidly entrenched, losses were very one-sided, with the British suffering almost 20,000 casualties and the Turks only 9000. Since these attacks occurred within 10–15km (6–9 miles) of the centre of Kut al-Amara, the noise, smoke and explosions were heard and seen by the beleaguered British. The British relief force continued to probe the Turkish defences throughout the following week, but without success. Nurettin’s basic operational concept had been clearly vindicated.

Turkish troops with a mortar at Kut al-Amara. This ancient, muzzle-loading mortar demonstrates how poorly equipped the Turks were in Mesopotamia. Such weapons were unheard of in other theatres of war, but the shortage of artillery called for such desperate measures.

In a desperate attempt to help Townshend continue resistance, the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service drew up a plan to drop supplies into the beleaguered town. From 16 to 29 April, British pilots dropped approximately eight tons of supplies, which included food, medicine and even fishing nets. These limited quantities could not materially alter the course of the siege, but they encouraged Townshend and his men to feel that the main army was trying every possible measure to assist them. The missions were not without risk and Turkish anti-aircraft fire and fighter aircraft attempted to thwart these efforts. This caused some missions to be abandoned. To make things worse, other pilots dropped supplies prematurely and into the Turkish lines.

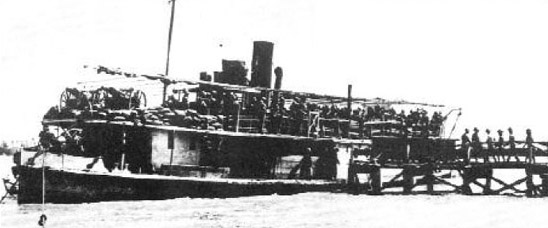

There was one final, sad chapter in the saga of the attempted relief of Kut al-Amara involving the steamer Julnar, which was a part of the British flotilla on the Tigris River. It was thought that if Townshend’s garrison could be resupplied, he might continue to hold out until the relief of the town. In the words of General Sir Percy Lake, ‘faint as the chance was, the Julnar, one of the fastest steamers on the river, had for some days been under preparation by the Royal Navy for an attempt to run the enemy’s blockade.’ At 8pm on 24 April 1916, with a crew of volunteers from the Royal Navy, the Julnar left Falahiyah carrying 270 tons of supplies in an attempt to reach Kut. While nominally under the command of the navy, the ship was in fact captained by a civilian volunteer named C.H. Cowley, who had been commissioned into the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve as a lieutenant-commander and had spent many years piloting on the Tigris River. The British laid down artillery and machine-gun barrages in the hope of distracting the enemy’s attention from the ship’s movement. The alert Turks, however, quickly discovered and shelled the Julnar on her passage up the river.

Arab prisoners of the British in Kut al-Amara. It is unclear whether these men were a military threat or criminals. It is likely that they were simple thieves who plagued the British lines of communications.

Passing the enemy lines astride the river, the Julnar drew more and more fire and eventually became entangled in cables that the Turks had drawn across the river. By midnight she lay grounded well behind the Turkish lines, where enemy infantry stormed the disabled ship. Townshend reported hearing heavy firing that night down river from Kut al-Amara, which suddenly ceased around midnight. The commander of the enterprise, Lieutenant H.O.B. Firman, was killed and the daring men of the Julnar were taken prisoner. The unfortunate, wounded Cowley was recognized by the Turks as a local river pilot, and there is some dispute today whether Cowley, apparently still in his civilian clothing, was summarily executed by the Turks or whether he pulled a pistol and went down fighting. In any event, he died a hero. The next day, British airmen confirmed that the ship was in enemy hands.

Townshend and his staff. Townshend’s initial battles against the Turks were well planned and well fought. At Ctesiphon he was outnumbered two to one. Had he not surrendered at Kut al-Amara, Townshend might have matured into an outstanding battlefield commander.

By 22 April Townshend knew that further resistance was useless and that he must surrender. Five days later he asked for terms, which, he hoped, would be generous. In particular, both his troops and the local population were completely out of food, and he asked therefore, above all, for immediate assistance in rationing his force and charges. There was much confusion as blindfolded staff officers were passed between the two armies, particularly over the exact terms of surrender. Finally, Townshend himself met with Halil Bey (the elderly, but indomitable, Goltz had died of cholera on 19 April) and attempted to buy his army out of captivity with a promise of a one million pound payment in gold. In fact, Thomas E. Lawrence (later famous as ‘Lawrence of Arabia’) was a part of this scheme, but it went sour and collapsed. Townshend also attempted to secure some sort of a parole. In the end, the honourable Halil Bey demanded an unconditional surrender, which Townshend was forced to accept. An Ottoman infantry regiment marched into Kut al-Amara at 1pm on 29 April 1916 to receive the surrender. Other than starving men, there was little to capture, as the British had spent two days destroying their artillery, ammunition and military equipment.

The surrender of Townshend’s 6th (Poona) Division was the largest of imperial troops between Yorktown in 1781 and Singapore in 1942. It was a terrible embarrassment for British arms, although the total number of soldiers lost was hardly a day’s worth of cannon fodder in the big battles then raging in Flanders. Townshend surrendered 13,309 men, including 2864 British, 7192 Indian and 3248 non-combatant troops. Over 4000 of these men subsequently died in Turkish captivity, and it is estimated that 70 per cent of the British prisoners died. Halil and Aylmer exchanged some 1100 sick and wounded British and Indian soldiers for an approximately equal number of unfit Turks. The Turks also recorded capturing 40 artillery pieces, three aircraft, two river steamers and 40 motor cars, almost all of which were damaged. The first Turkish food supplies arrived by relief boat on 1 May 1916. Townshend and his aides were sent to Baghdad two days later and the Turks began to evacuate their prisoners the following day. The first British to leave Kut al-Amara after Townshend were four generals, 160 officers and 180 of their personal aides, by boat. Townshend’s British and Indian soldiers, however, were marched north in columns, often without adequate water, food or medical supplies. As a consequence many died in what some have termed a ‘death march’. In the space of just over a year, the British lost 40,000 men in Mesopotamia. Colonel Halil Bey became an overnight hero and received the honorific ‘Pasha’. Later, in the Turkish republican era, he would choose the surname ‘Kut’. For his part, Townshend went into comfortable captivity on an island in the Sea of Marmara, while his surviving men endured hard conditions in Anatolian POW camps.

British forces captured at Kut al-Amara. The Turks also captured a number of motor cars along with artillery, aircraft and stores. Most were deliberately damaged beyond repair prior to the British surrender.

The heavily armed and sandbagged Julnar looks dangerously top heavy in this photo, with two artillery pieces facing forward. She was captured on 24 April 1916.

A shocked British Government demanded to know what had happened, and, since it came close on the heels of the Dardanelles disaster, convened a parliamentary commission. The testimony focused on administrative, logistical and medical problems, as well as the institutional weaknesses of the Indian Army. The report of the commission appeared in 1917 and largely blamed factors internal to the British Army for Townshend’s humiliating defeat. In truth, it was Nurettin’s aggressive pursuit and lines of circumvallation that defeated him, along with the defensive qualities of the Ottoman Army.

With the surrender of Townshend at Kut al-Amara, the campaign in Mesopotamia entered a period of stalemate. The fighting had exhausted both sides, and without Townshend to rescue there seemed little reason for the British to hurry up river. Halil Bey began to slowly redeploy his forces downstream, carefully fortifying both banks of the Tigris and finally finding enough surplus forces to fortify the Euphrates as well. There was little activity in Mesopotamia for the remainder of 1916 until December, when a renewed and greatly reinforced Imperial force under General Sir Stanley Maude again began the slow march up river.

Despite Goltz’s death, Enver Pasha journeyed to Baghdad in mid-May 1916 to confer with Halil Pasha and Colonel von Lossow about the prospects for a renewed offensive against Persia. In the aftermath of the victory at Gallipoli, Enver had troops deploying to Mesopotamia; however, the surrender of Kut al-Amara in April made their presence in the Tigris–Euphrates Valley redundant, and Enver was eager to use them in an offensive capacity. The 2nd Division was already at Kut al-Amara and its sister divisions, the 4th and 6th, were due in theatre by the end of the month. All of these divisions comprised battle-hardened veterans of the Gallipoli campaign.

Enver’s ambitious invasion plan called for Halil’s XIII Corps to detach the 35th and 52nd divisions to its Sixth Army sister XVIII Corps, and to receive the fresh and rested 2nd, 4th and 6th divisions. An independent cavalry brigade, some irregular units and Persian nationalist volunteers would augment the corps. Lossow also promised German artillery, but this never arrived. Altogether, XIII Corps would total around 25,000 men to oppose a Russian army of several divisions in Persia, but the Russians were widely spread out.

XIII Corps, commanded by Ali Insan Pasha, began its advance in late May after concentrating on the frontier. However, the ever-aggressive Russians attacked the 6th Division and attempted to encircle it together with the XIII Corps headquarters in the border town of Hanikin on 3 June. The Russians came close to succeeding, but their thinly spread infantry battalions were held in check while the centrally positioned Turks crushed the encircling Russian cavalry. Threatened with defeat in detail, the Russians withdrew. Soon after, XIII Corps crossed the Persian frontier, which consisted of rugged mountains with narrow valleys that made offensive operations difficult. General Baratov, the Russian commander, conducted a skilful fighting retreat. The main Turkish force, the 2nd and 6th divisions, advanced through the mountains along the main road to Kermansah. On the Turkish left (or northern) flank, the 4th Division crossed the frontier from Süleymaniye and pushed east towards Sine and Kurve. This division was reinforced with some Persian volunteer battalions and was now styled the Mosul Group. The main force encountered strong Russian defences near Karind and halted to prepare an attack.

Townshend enters Turkish captivity. He was treated well by the Turks, living in a villa on the Prince’s Island at the mouth of the Bosporus. He was accorded free movement in Constantinople, while his men suffered cruelly and died in prisoner of war camps.

The Turks attacked on 28 June, taking Karind two days later. By now XIII Corps was over 150km (93 miles) beyond the frontier and the Russians continued to retreat. Finally they concentrated for a stand at Hamadan. After a hard-fought, six-day battle, XIII Corps took the town on 9 August 1916. Baratov pulled back another 100km (60 miles) to block key mountain passes while awaiting reinforcements. The distances were too great to sustain Ali Insan Pasha’s corps logistically, and his offensive came to a halt. Combat casualties in XIII Corps were very light, but diseases, such as cholera and typhus, had ravaged the corps on the march to Hamadan. With the main body of XIII Corps at Hamadan and the 4th Division forward of the frontier at Süleymaniye, the corps was too spread out for mutually supporting offensive operations. Moreover, Ali Insan Pasha had been told that large numbers of Persian volunteers would join him; however, few actually came to help. For these reasons, he decided that his force was insufficient to continue the conquest of Persia and halted operations. This ended the second invasion of Persia, and XIII Corps limited its activities to a series of patrols to the north and east of Hamadan.

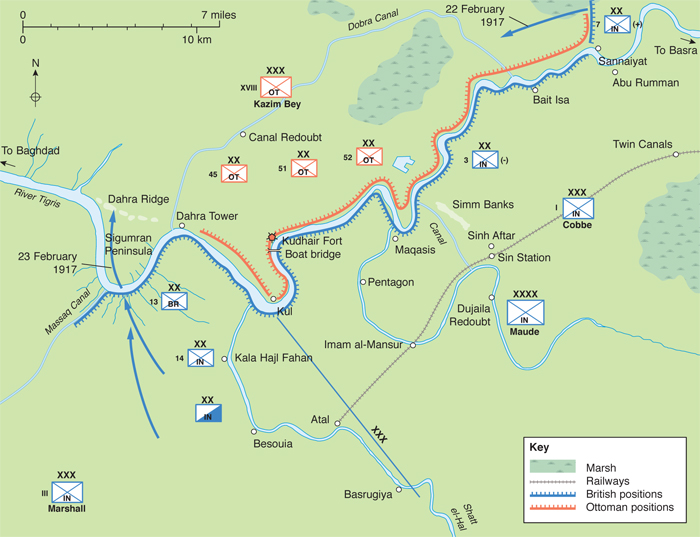

The British made important improvements in their army in Mesopotamia after the disastrous failures before Kut al-Amara in the spring of 1916. Most importantly, the defeated commanders were relieved and the aggressive General Maude was sent out to assume theatre command. Also, the Imperial force in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys was to increase its strength, by sending two additional infantry divisions (the 13th Division from Gallipoli and the 14th Indian Division) to reinforce Maude. Even the defeated Tigris Corps was renamed I Indian Army Corps. Maude was determined to avenge the defeat of Townshend.

Von der Goltz, in his role as Governor General of Belgium. The field marshal was the most respected German officer in the Ottoman Empire. He had served with the Turks in the 1880s and 1890s, and had helped train both their staff officers and their army.

Von Lossow was a consummate German general staff officer who spent much of the war serving at the Ministry of War in Constantinople, helping plan the Ottoman war effort.

As the summer of 1916 turned into autumn, Maude planned an advance up the Tigris to break Halil’s grip on the gateway to Baghdad. He now had a large force concentrated under his direct command, with a total of five infantry divisions, well supported by cavalry, artillery and aircraft. Additionally, he built up a large and capable river flotilla of armed steamers and supply vessels. Maude had a fighting strength of 166,000 men, of whom 107,000 were from the Indian Army. In spite of the high numbers of men and equipment, Maude was determined not to advance until he was fully ready, and resisted political pressure.

Because of strategic diversions elsewhere (such as Persia, Galicia and Salonika) and because of chronic weaknesses in rail communications, the Ottoman general staff did not augment the Sixth Army’s strength in the final nine months of 1916. Moreover, Halil Pasha received very few individual replacements for his losses, which grew larger with each passing day. Slow attrition from disease, desertion and occasional British activity continually wore away his army. Thus, while General Maude’s army grew in size and capability, Halil’s steadily grew weaker. Enver’s scheme to invade Persia further reduced his uncle’s army. By summer 1916, Halil’s force contained only XVIII Corps comprising the 45th, 51st and 52nd divisions.

He also found it necessary to inactivate the unfortunate 35th Division and reassign its soldiers to one of his remaining three infantry divisions.

The Ottoman Sixth Army faced an untenable operational situation, which was exaggerated by the geography of the Tigris and Euphrates River basin itself. There were two avenues of advance into Mesopotamia available to the British. The best route lay north up the Tigris River, along which lay Kut al- Amara, Baghdad and Mosul. The second route followed the Euphrates River, via the ruins of Babylon, to a point about 30km (18 miles) west of Baghdad. However, in the summer of 1916, the British forward positions were located not at this narrow gap, but instead at the widest distance between the two rivers. Halil was thus forced to defend two separate defensive positions with about 100km (60 miles) of desert between them. This invited defeat, because Maude could choose his point of attack, massing superior forces there, before Halil could react. Consequently, Halil faced an almost impossible strategic and operational situation.

The Second Battle of Kut al-Amara, February 1917. By 1917, General Maude’s heavily reinforced army was able to easily outflank Kazim’s severely depleted force. Maude made Kazim retreat beyond Baghdad.

Turkish prisoners in British captivity, such as those shown here, usually received better rations and medical care than when active in the service of their own army.

In December 1916, Maude began his long-awaited offensive. The Turks were anxious to identify which river approach the British would take as their primary axis of advance. Maude chose the Tigris and advanced with a full-strength corps on either side of the river towards Kut al-Amara. Rains slowed his advance, but by 17 February 1917 his army had reached Sannaiyat, about 20km (12.4 miles) downstream from Kut al-Amara, where Aylmer’s relief force was defeated. Maude’s deliberately slow pace made it possible for Halil to shift most of his meagre forces to reinforce XVIII Corps, which held the line there. Thus, by mid-February 1917 the Turks had the entire XVIII Corps, commanded by Colonel Kazim Bey, in the old defensive positions originally established by Nurettin. Kazim Bey also commanded the River Group, equivalent to a division in combat power. As a percentage of his available strength, Halil was able to mass over 75 per cent of his small army to oppose Maude.

Maude was born in Gibraltar and educated at Eton before entering Sandhurst. He was commissioned into the Coldstream Guards and saw service in Egypt and the Second Anglo-Boer War. Maude held a series of general staff positions and in October 1914 he was promoted to brigadier-general and given command of the 14th Brigade. He was seriously wounded in April 1915 in France and promoted to major-general. Maude was assigned to command 33rd Division but instead was reassigned to 13th Division at Suvla Bay. After evacuation from Gallipoli, Maude’s division was sent to Mesopotamia in March 1916. With the failure to relieve Townshend, Maude moved up to corps command in July 1916 and overall command shortly thereafter. He immediately set about reorganizing and re-supplying the British and Indian forces in Mesopotamia. His thorough approach to war led to the victory at the Second Battle of Kut al-Amara and the capture of Baghdad in March 1917. Maude died on 18 November 1917 of cholera.

British troops entering Baghdad. The Mesopotamian campaigns were never fully resourced by either the War Office or the India Office, and the forces there suffered from inadequate logistical support for most of the war.

Almost all of Colonel Kazim’s corps deployed on the north bank of the Tigris in an attempt to defend the most likely approach to Kut al-Amara. However, Maude unexpectedly shifted both of his corps to the south bank and began to mass on the Turkish right flank towards Kut al-Amara. Halil was unaware of the true situation and sat in his lines waiting for Maude to move. The first attacks began on 17 February, and five days later Maude initiated demonstrations at Sannaiyat and at Kut al-Amara to further confuse Halil. On 23 February Maude began a divisional-size assault crossing of the Tigris up river from Kut al-Amara, and by the end of the day had a pontoon bridge across the river. Local Turkish counterattacks were unsuccessful in dislodging the bridgehead. Most of Halil’s strength and his reserves remained in now useless positions down river from Kut al-Amara and by nightfall he realized that his corps was threatened with encirclement from the north. He reacted promptly and ordered an immediate withdrawal. XVIII Corps began to pull out of its defensive positions that very night. Desperate rearguard actions bought enough time for Halil to evacuate most of his infantry, but he was forced to abandon most of his artillery and supplies. Halil withdrew up river for the final defence of Baghdad. Maude’s campaign, long in coming, was brilliantly executed and showed great agility at the operational level. He understood that it was almost impossible to force the Turks out of their strongly held trenches, and he used manoeuvre to render Halil’s position untenable.

British troops on the march. The campaign season in Mesopotamia effectively lasted from October through April, when the temperatures permitted active field operations. Low water in the rivers impeded summer operations as well.

Halil withdrew to the Diyala River line, along a small tributary entering the Tigris about 15km (nine miles) below Baghdad, where he tried to make a stand. He inactivated the 45th Division, which was far below strength and without artillery, and assigned its survivors along with two newly arrived infantry regiments to form the 14th Division. This division became part of XVIII Corps to assist in the defence of Baghdad. Maude resumed his relentless march up river on 4 March and attacked the tired and dispirited Turkish troops along the Diyala. After several days of hard fighting, it was clear to Halil that he could not hold the Diyala or Baghdad itself. Although reluctant to surrender this city with its great political, cultural and religious significance, Halil made the bitter decision to abandon Baghdad and continue his retreat up river. On 11 March 1917, Maude took Baghdad and avenged Kut. His victory came at a time of stalemate in other theatres, and cheered the British public. In contrast, it was a new low point for the Turkish Army and one that could not easily be remedied.

Halil took his now tiny army about 60km (37 miles) up the Tigris. His right flank lay at Ramadiye on the Euphrates and his left flank extended along a weak line into Persia. Halil then moved himself and his army headquarters far up the Tigris to Mosul. His total force, at this time, amounted to little more than 30,000 men and was spread over 300km (186-mile) front. In April the 2nd Division returned from the poorly advised Persian expedition; however, this was too little too late and did not alter Halil’s position. For the Turks, the overall strategic situation in Mesopotamia, in the late spring of 1917, appeared hopeless.

Then, surprisingly, General Stanley Maude stopped advancing. Maude’s supply lines stretched back to Basra and were getting longer with each mile he advanced. Moreover, the summer season of disease was upon the region. Maude was also concerned over how and when the Russians might support him in Persia and he possessed intelligence that the Turks were preparing a massive counter-offensive with a new force (the Yildirim Army) aimed at the recapture of Baghdad. He requested but was denied reinforcements. As a consequence, Maude decided to remain on the defensive in Baghdad and renew his offensive in the autumn. His decision was, in retrospect, cautious and it is doubtful whether the Sixth Army could have prevented further British attacks, or held Mosul, had Maude continued his advance. Indeed, considering the huge disparity in combat power and logistics, it is remarkable that Halil held the British back for as long as he did. In the end, it was Maude’s understanding that it was Townshend’s fatal overextension at Ctesiphon, under political pressure to advance, that had led to the disaster at Kut al-Amara. He was determined not to repeat this error, and the war in Mesopotamia stabilized in March 1917 with the British in possession of Baghdad.

In Persia, casualties and unreplaced losses forced an operational pause on both the Turks and the Russians, which lasted from August 1916 into the winter. XIII Corps did receive a trickle of replacements and reinforcements, including some battalions of Muslim North African deserters from the French Army. In February 1917, Halil made the difficult decision to recall Ali Insan Pasha’s corps and over the next month it withdrew over 400km (250 miles) through the mountains in winter conditions. By mid-March, XIII Corps had been evacuated from Persia and its forward elements were arriving along the Diyala line. Meanwhile, the events of 1917 overtook the Russians, as discontent and revolution swept through their army. XIII Corps now took up the task of the defence of Mesopotamia.

The summer of 1917 passed uneventfully, as the torrid heat prevented active operations. In the autumn, Maude began minor operations, but remained in place. Then, unexpectedly, he died on 18 November 1917 of cholera in Baghdad. Maude’s death ended any real possibility of continued offensive operations in Mesopotamia and it remained a quiet backwater of the war. The Turks were more than happy not to disturb the status quo. Maude’s replacement was General Marshall, who finally launched an offensive in March 1918 to outflank the Turks at Khan Baghdad. This offensive failed, but Marshall managed to inflict severe losses on the Turks.

However, events took a different turn as the great Ludendorff offensives on the Western Front in March 1918 made a dramatic impact on the British posture in the Middle East. The German Spring Offensives were aimed at knocking the BEF back to the Channel and isolating it from the French. During these battles, the British took heavy casualties and experienced a shortage of infantry on the front (although replacements were available in Great Britain, political pressures kept them at home). In any case, the Imperial general staff directed General Allenby in Palestine to send about 60,000 trained British soldiers to France. In all, Allenby sent two full divisions, 23 infantry battalions, nine cavalry regiments and artillery and machine-gun units, causing his army’s strength to fade. However, some ‘Easterners’ in London felt that Allenby’s campaign had great potential politically and wanted it to continue as a priority effort. In the end, Marshall’s army in Mesopotamia became the bill payer and was forced to send two Indian Army divisions to Palestine (the 3rd and 7th) to replace the men Allenby had sent to France. Moreover, the replacement flow of men from India was diverted to Allenby rather than Marshall. This drained Marshall’s strength and drew his army down to something of a caretaker garrison for Baghdad. Throughout the summer of 1918, the British in Mesopotamia did nothing.

‘With the failure of the Julnar there was no further hope of extending the food limit of the garrison of Kut.’

Sir Percy Lake, dispatch, 1916

All of this changed with Allenby’s great victory at Megiddo and the collapse of the Salonika perimeter. On 2 October 1918, Marshall received instructions to gain as much ground as possible should the Ottoman Empire ask for an armistice. Marshall began to push up river, again meeting the divisions of XVIII Corps, and on 23 October the British attacked over the Little Zab River. Outflanking the Turks, Marshall’s cavalry encircled the surviving men of Ismail Hakki’s Tigris Group, which surrendered on 30 October. On the same day, an Ottoman delegation signed the armistice ending the war in the Middle East. Marshall, under pressure from London to gain control of the important oil fields at Mosul, put his fast-moving cavalry on the road the next day (in violation of the armistice agreement). On 1 November 1918, British cavalry rode into the undefended city of Mosul and took control of it (along with the vital oil fields). The Ottoman Sixth Army remained in being as did XIII Corps, but they were shadows of their former selves and could not stop Marshall’s occupation of the city. With this episode, the war in Mesopotamia came to an end.

While 1916 was a year of triumph for the Turks at Gallipoli and Kut al-Amara, it was a year of disaster in the Caucasus. In truth, the victories over the British came as an unexpected surprise to the general staff, and it was unprepared to deal with the consequences of success. At the end of the Gallipoli campaign a large surplus of infantry divisions became suddenly available and many, including Mustafa Kemal, thought that the empire should remain on the defensive and use them as a reserve. Enver Pasha, however, remained committed to offensive operations, and instead of keeping these formations concentrated and available, he sent them off to distant theatres in penny packets.

In the Caucasus in January 1916 the front was quiet, and the Ottoman Third Army stood on the defensive along the frontier northeast of Erzurum. The army was understrength and its three corps contained an average of about 12,000 men. Overall, the Turks had about 125,000 men, while the Russians had over 200,000 available. The Turks believed that the harsh winter precluded offensive operations and were surprised when General Yudenich attacked on 10 January 1916. Yudenich’s main effort was a frontal attack on XI Corps, which held a series of strongpoints rather than a line of continuous trenches. This allowed the Russians to infiltrate the Turkish positions and push them out of their lines. The disorganized Third Amy retreated in disarray and fell back to the fortress of Erzurum, losing some 10,000 men (mostly from XI Corps). Erzurum was heavily fortified and well armed with over 200 cannon, and was the third most powerful fortress complex in the Ottoman Empire. It had kept out the Russians in previous wars, and was believed to be secure.

A British officer wearing a gas mask in Mesopotamia in 1917. Although gas was never used in Mesopotamia, it was used by the British during the Gaza battles. The results were ineffective and it was never used again in the Middle East in World War I.

A British gun barge. Command of the rivers was an important consideration and both sides employed riverboat flotillas. Because of the swampy nature of the terrain, both sides used barges as mobile field artillery firing platforms.

To the surprise of the Turks, General Yudenich closed on the fortress at the end of the month and continued his offensive. Simultaneously, the Russian launched supporting offensives in the north towards Trabzon and in the south towards Malazgirt, while Yudenich brought his artillery forward. On 11 February 1916, he unleashed an intense bombardment on two of Erzurum’s forts and then launched a night attack with infantry. The fighting inside the forts, hand-to-hand, ended with small groups of survivors holding isolated tunnels and gun positions. As dawn broke the Russians held a deep salient, which was immediately (but unsuccessfully) counterattacked by the Turks. A final Russian push of five columns on different axes led to the fall of the city on February 1916. This was a disaster for the Turks as the fortress was the lynchpin of the entire defence of eastern Anatolia. Third Army managed to conduct a fighting retreat saving most of its infantry, while Yudenich’s army captured hundreds of guns, stores and the hospitals of Erzurum.

In fairness, the understrength army corps of Third Army held frontages of over 30km (18.6 miles), while their counterparts at Gallipoli held six. This diffused the Turk’s ability to concentrate combat power on the front lines. Enver relieved the commander and sent Vehip Pasha out to take command of the defeated army, which was now reduced to about 50,000 men and 84 guns.

Belatedly, Enver recognized that the strategic posture of the Caucasus resembled a house of cards waiting to collapse. He directed the general staff to start sending 10 of the Gallipoli divisions east on 1 March. His intent was not to reinforce the defeated Third Army and retake Erzurum. Rather, Enver wanted to form a new Second Army in the east and conduct a counter-offensive to push the Russians entirely out of Anatolia. It was wildly optimistic and he expected to be able to do this by June 1916. Unfortunately, the abysmal and antique Ottoman railway system did not reach into the Anatolian hinterlands and, furthermore, Enver dispatched the divisions slowly and individually. It was a terrible mistake and illustrated the inexperience of Enver in matters regarding higher strategy. Over the spring and early summer these forces arrived in penny packets in Caucasia along the Black Sea and along the southern flank, while none went directly to Third Army holding the vital centre.

The relentless Yudenich continued his offensive in July 1916 and rapidly took the city of Bayburt, before capturing the key city of Erzincan. These defeats essentially destroyed the Third Army as an effective fighting organization. Meanwhile, in the midst of these disasters, the Gallipoli divisions made their way eastward and were held inactive over the summer as the new Second Army formed on the long southern flank of the Anatolian front. It grew slowly into a powerful force of 12 infantry divisions and one cavalry division. Finally, the long-awaited Second Army offensive began on 2 August 1916, commanded by the capable Ahmet Izzet Pasha. Because of Russian weakness, instead of concentrating his army, he formed three operational groups on separate axis of attack. This was possibly the best army the empire had put together during the war, composed of veteran formations, and Ahmet Izzet launched it northeast towards Erzurum. Unfortunately, the slow deployment gave plenty of notice to the Russians, who planned accordingly and while the Turks enjoyed localized success, overall they met with failure. Well prepared defences and heavy Russian counterattacks defeated Ahmet Izzet’s three groups in detail. By the end of September the offensive was finished with 30,000 casualties out of 100,000 who went forward. This was one of the worst mistakes made by the Ottoman Empire in the war. Had the divisions of this army been fed into Third Army as they arrived, the tactical balance would certainly have been altered in the Turks’ favour. Enver’s gamble on offensive operations resulted in the loss of huge amounts of territory and the destruction of two armies.

Although the Russian armies in Caucasia contained some Cossack regiments, such as this one, cavalry was of little real use in the heavily mountainous region. Most of the Ottoman cavalry stationed there was redeployed to Palestine.

The Russian Army conscripted men locally, and there were a number of Islamic regiments on its rolls in the Caucasus. This photo depicts the regimental colours from an Islamic and a Christian regiment.

As the cold weather set in in the autumn of 1916, a lull in the fighting occurred that gave both sides the opportunity to regroup their hard-pressed forces. For their part, the Turks formed the Anatolian Army Group and started to reconstitute their Caucasian armies, which by now had grown to a substantial 25 divisions. However, all of these divisions were worn down to half strength and, in many cases, to a quarter of their authorized strength. The Third Army commander, Vehip Pasha, was convinced that his Third Army’s morale was so battered by nine months of defeat that it needed to be rebuilt from the ground up; Enver approved a radical plan to do so. As there were simply no replacements available to stand in for losses, Vehip dissolved eight entire infantry divisions and distributed the men to his remaining divisions. However, even this extreme action only brought them up to two-thirds of their normal authorizations. Vehip then created what he styled ‘Caucasian divisions’ and reorganized them into two new ‘Caucasian corps’ (he also dissolved the unfortunate IX, X and XI corps). Typically, Vehip immediately started an intensive training programme and quickly erased the stigma of defeat. It was a remarkable turn around that returned Third Army to an effective force. The Second Army also inactivated three divisions and sent two more to Palestine, becoming a shell of its former self.

By the end of 1916, the situation in the Caucasus was stable, but the Turks had lost the critical Erzurum fortress, the cities of Bayburt and Erzincan and the key coastal port of Trabzon. Over the course of the year they suffered several hundred thousand casualties, including almost 70,000 killed and 27,000 POWs. It was a disaster, but fortunately for the Ottomans, Russia was about to enter a year of revolutions and strife that would paralyse the offensive capacity of its Caucasian armies. The year 1917 in the Caucasus would prove to be one characterized by almost total inactivity, as both sides observed something of an informal truce.

At the end of the Gallipoli campaign, the Ottoman Army was left with a surplus of 20-odd infantry divisions clustered around Constantinople. During the spring of 1916, Enver Pasha responded to this situation by promising his German and Austrian allies assistance in the Balkans. Over the year, he would send seven infantry divisions deep into Europe on campaigns of marginal value to the strategic interests of the Ottoman Empire.

In early October 1915, a two-division Anglo-French expeditionary force landed at Salonika, Greece (which was then neutral), in a vain attempt to drive up the Vardar Valley to relieve Serbia, then collapsing under a combined attack by Austria, Bulgaria and Germany. This endeavour, like the Dardanelles operation, was the result of a hotly contested decision by ‘Easterners’ and ‘Westerners’ in London and Paris, and reflected to a great degree the increasing frustration with the stalemate on the Western Front. There was probably more enthusiasm in France for the Salonika expedition, but it was too little too late and the Central Powers easily crushed their tiny opponent. However the Serbs refused to surrender and their army retreated to the Adriatic coast where it was evacuated by the Allied navies and reconstituted in the Salonika entrenched camp, where it again joined the Allied ranks. To assist in containing the Allied perimeter, Enver sent XX Corps, composed of the 46th and 50th divisions, to Macedonia in the autumn of 1916. These divisions saw little hard fighting, and were withdrawn in the spring of 1917.

The Russians captured a considerable number of Ottoman prisoners of war. However, both food rations and medical care were inadequate for these men, and many did not survive captivity.

Turkish troops in Salonika practise firing at enemy aircraft in 1917. The Vietnamese used this World War I tactic of anti-aircraft defence in the Vietnam War against American aircraft. It was occasionally successful in both conflicts.

To the north, the Brusilov Offensive of June 1916 had a crushing effect on the Austro-Hungarian Army by inflicting a defeat of huge scale. This created a manpower shortage on the Eastern Front that the Germans attempted to fill. However, they were then engaged on the Somme and at Verdun and were unable to completely solve the problem. General Erich von Falkenhayn asked the Turks to assist by sending as many men as possible. Enver Pasha responded by ordering XV Corps, comprising the veteran 19th and 20th divisions from Gallipoli, to prepare for movement to Galicia. XV Corps was well equipped by Ottoman standards and the Germans augmented it when it arrived in August 1916. Over the next year, the corps fought in many defensive actions, but managed to hold its sector intact along the Zlotalipa River. For the first time, Turkish soldiers were exposed to poison gas shells, but the Germans had provided them with gas masks and they weathered the barrage with few casualties. As the Russian war drew down in the summer of 1917, the general staff brought the corps home before sending it to Palestine.

By far the largest commitment of Ottoman divisions in Europe after Gallipoli came when Romania entered the war on 27 August 1916. Although the Romanians opened the war with an attack on Austria-Hungary, the Germans and their allies were well prepared for this contingency and conducted an attack of their own. This involved an enveloping offensive by General Erich von Falkenhayn from the northwest and by a joint German– Bulgarian–Ottoman army group commanded by General August von Mackensen from the south. Enver sent VI Corps (15th and 25th divisions), which began combat operations on 18 September, against the Romanians. The Turkish operations were characterized by well conducted attacks and by vigorous pursuits of the battered enemy forces. As winter set in, Enver dispatched the 26th Division to bring the corps up to full strength, and by mid-January 1917 the Romanian Army was decisively defeated and had been ejected from its own country. The Turks lost about 20,000 men in this campaign; however, they maintained VI Corps in Romania until the spring of 1918, when it was finally brought home.

Altogether in 1916 (counting the residual Gallipoli front at Cape Helles), the Ottoman Empire fought on seven active fronts (eight if the Arab Revolt is considered). In his zeal to be an equal partner of his allies, Enver Pasha sent his soldiers to places that were not critical to the Ottoman Empire’s war effort. This had unfortunate consequences and contributed to the disasters in the Caucasus, Mesopotamia and Palestine.

Falkenhayn was born in West Prussia and served as a military instructor to the Chinese Army. He attended the Prussian War Academy and became a general staff officer. During the Chinese Boxer Rebellion (1900) he saw action in the relief of Peking. Falkenhayn continued to serve on the German general staff, and was appointed Prussian Minister of War in 1913. In September 1914 the Kaiser dismissed Moltke from his post as chief of the general staff and replaced him with Falkenhayn. He believed that France could be defeated by an attritional strategy and was responsible for the planning of the Verdun campaign, which was as disastrous for Germany as it was for France. Consequently, he was replaced by Hindenburg and sent to command against the Romanians in the autumn of 1916. There Falkenhayn recovered some of his reputation and was next sent to Palestine to command the Ottoman forces in early 1917. After losing Gaza and Jerusalem he was replaced by Liman von Sanders in February 1918. Upon his return to Germany he retired.

Falkenhayn is shown here on the left.