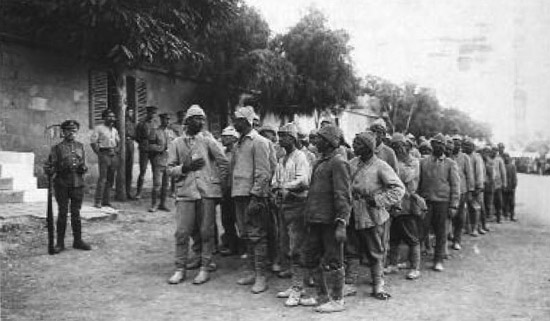

German officers head a line of Ottoman prisoners captured near Jericho in July 1918. Desertion and the wilful surrender of soldiers in combat were a major problem in Palestine.

The string of British victories in Palestine in the closing months of 1918 led to Erich von Falkenhayn’s replacement. The Palestine front was now brought under a single Ottoman commander, but the Allied advance was relentless. At Megiddo, the British smashed through the Turkish defences. In the Caucasus, by contrast, Ottoman forces made considerable gains.

In Palestine, Allenby’s offensive finally ground to a halt north of Jerusalem. This was a result both of torrential rainstorms in the last week of 1917 and the exhausted condition of his soldiers. This temporary respite allowed the Turks a brief period in which to recover their operational effectiveness. However, in February 1918 Allenby renewed his offensive by ordering an attack on Jericho, hoping to force the Ottoman XX Corps back across the Jordan River. The attack began on 19 February and the battered Turks were once again forced to withdraw. However, they were now behind the east bank of the Jordan River, which offered them a fine natural defensive obstacle, and were able to dig in.

Despite this small success, the string of Ottoman defeats that began at Gaza led to the relief of General Erich von Falkenhayn. The Turks were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with his advice and command style. Although most of the blame for the defeats at Gaza and Beersheba could be laid at the feet of Kress, Falkenhayn was held responsible. Part of his troubles were also caused by his contempt for Ottoman officers and by his refusal to allow them to participate in planning important combat operations. Falkenhayn’s reputation as a commander of multi-national armies that he had established in Romania was coming undone as his efforts to stop Allenby failed again and again. It became fashionable in Constantinople to remember Falkenhayn’s disastrous handling of the Verdun operation and his failure to hold the Gaza–Beersheba line, rather than for his success in Romania.

‘The policy of Falkenhayn was defence by manoeuvre; that of the Liman defence by resistance in trenches.’

Cyril Falls, Military Operations, 1926

Following the exit of Falkenhayn, the problem remained of who to appoint as theatre commander. Despite their frequent disagreements about the war and the treatment of Armenians and Greeks, Enver Pasha valued the fighting abilities of Liman von Sanders, who had won the Gallipoli campaign. Enver approached Liman von Sanders on 19 February with an offer to command the Yildirim Army Group. The German, tired of being sidelined in Turkish Thrace, eagerly accepted his offer several days later. Enver also took the opportunity to separate the Mesopotamian theatre from the Yildirim Army Group, which simplified its responsibilities. Enver also ordered Cemal’s Fourth Army in Syria to coordinate its operations with the new command, which finally brought the Palestine front under a single commander. On 8 March, after a difficult railway journey, Liman von Sanders and his staff arrived in Syria; he consulted the departing Falkenhayn about the defensive strategy for Palestine. There were significant differences of tactical and operational opinion between the two generals. Falkenhayn was an advocate of a flexible defence, which allowed for both retreat and for the surrender of ground. Liman von Sanders, based on his personal experiences on the Gallipoli Peninsula, was an advocate of a theory of static tactical defence, which dictated that ground should be retained at all costs and if lost, immediately retaken by counterattacks. Liman von Sanders was unhappy with the Yildirim Army’s dispositions and plans, and he immediately began to reverse the operational and tactical direction of the defence of Palestine.

The British conducted another offensive shortly after Liman von Sanders’s arrival, with the objective of establishing a bridgehead on the east bank of the Jordan. Famously, this offensive was conducted in concert with large-scale Arab raids on the Dera–Hedjaz railway and was preceded by diversionary attacks across the entire front. The main attack began on 21 March; the British launched two infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions across the river, breaking the back of the Ottoman lines on the Jordan River. Allenby wanted to seize Amman, cut the railway and then ‘probably withdraw’. He hoped to outflank the main Turkish lines and perhaps break loose from the deadlocked trenches. By 30 March, the British had pushed the 48th Division back into the city of Amman, on the Hedjaz railway. However, for reasons that remain unclear Allenby called off the attack and withdrew the next day. Certainly, the stated reason that the Turks had brought up substantial reserves, which offset the numerical advantage of the British, is not true. The possession of the city of Amman would cut, once and for all, the Dera–Hedjaz railway and also offered the opportunity to outflank the strong Ottoman main defensive lines. It was an important objective for the British, and the abandonment of their attack was probably due to the fact that Allenby had been ordered to send troops to France. The Turks conducted a vigorous pursuit and compressed the withdrawing British into a bridgehead in the Jordan River valley. After a bloody repulse on 11 April, the Turks halted their counterattacks and began to dig in. This engagement became known as the First Battle of the Jordan.

The mayor of Jerusalem, Hussein Effendi, meets men of the 2/19th Battalion, The London Regiment under the white flag of surrender on 9 December 1918 at 8am. Relations between Ottoman civil servants in occupied areas and the British were generally correct, as this photograph suggests.

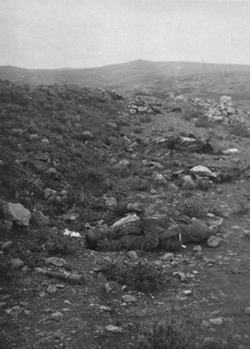

Bodies of Turkish troops after an attempt to capture the city of Jerusalem on night of 26/27 December 1917. Ottoman counterattacks in late 1917 restored the situation and stabilized the lines once again. It is possible that these dead men were from a stormtroop detachment.

On 30 April the Second Battle of the Jordan began, when the British again launched an attack toward Amman from their bridgehead on the east side of the Jordan. In the intervening two weeks, the Turks managed to bring up strong forces (24th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division), which were available to conduct a flank attack on the advancing British. These divisions, along with Ottoman stormtroop battalions, conducted strong counterattacks between 2 and 4May that swiftly halted the British offensive. Fighting along the Jordan died down until mid-July 1918, when brief (though bloody and inconclusive) attacks were conducted by both sides.

Palestine was relatively quiet during the spring and summer of 1918 (with the exception of the skirmishing along the Jordan River). The understrength Ottoman Army did not have sufficient combat power, while Allenby’s army was stripped of experienced formations for reinforcements for the BEF in France, which was reeling from the heavy Ludendorff offensives in the spring of 1918. Allenby was ordered to send to France, beginning in March, two infantry divisions, nine yeomanry (cavalry) regiments, 24 British infantry battalions, five heavy artillery batteries and five machine gun companies. To maintain his strength, the India Office sent him two Indian Army infantry divisions from Mesopotamia, and a number of Indian cavalry regiments and infantry battalions as well as thousands of individual replacements. Allenby lost a significant portion of his trained and experienced British Army combat power, and in return received inexperienced and less well trained Indian troops. These events forced Allenby to spend the summer engaged in a complete reorganization and retraining of his army.

The British were still left with seven full-strength infantry divisions in Palestine, but the national character of these formations had changed significantly. Only a single all-British infantry division remained (the 54th Division); four other ‘British’ divisions were actually the 2nd/3rd Indian (the 10th, 53rd, 60th and 75th divisions), and the final two divisions were Indian Army infantry divisions (3rd and 7th Indian divisions). Only in mounted strength did Allenby’s situation actually improve, gaining one division, for a total of four mounted divisions.

Allenby still commanded a large and well equipped army with which to renew the offensive against the Yildirim Army Group. Unfortunately, many of the newly arrived Indian soldiers were untrained or unseasoned in combat. Of 54 incoming infantry battalions, 22 had combat experience but had given up a company of men, 10 were composed of combat veterans who had not trained together, and 22 had seen no active service whatsoever. This situation forced the EEF to begin a long training programme that lasted throughout the summer as Allenby prepared his army for offensive operations. Fortunately for the British, the EEF had in Allenby one of the finest trainers in the army.

Allenby’s training programme was vigorous and comprehensive. He began with the careful integration of the incoming Indian Army battalions into the gutted divisions by linking one British infantry battalion with three Indian battalions to form new brigades. Moreover, some of the remaining individual British officers and NCOs were earmarked to receive elementary training in Indian languages to assist in the integration process. The staffs enlarged the available system of tactical schools that existed in Egypt and in the rear areas of the army. This included heavy machine-gun, Lewis gun, rifle grenade, signals and small-unit tactics courses and the incoming Indians received allocations and were programmed into the training cycles. There were also courses for company commanders and staff officers as well as individual training for raw recruits.

The reorganized Ottoman Gendarmerie in Barracks Square, Jerusalem, 1918. The gendarmerie (Jandarma) was a paramilitary organization that fell under the Ministry of the Interior in peacetime and the Ministry of War in war.

Importantly, Allenby also ensured that the latest ‘lessons learned’ from the Western Front were integrated into his training programmes. The EEF reprinted pamphlets that brought the most recent developments in tactics to the army in Palestine. These were supplemented by frequent lectures at brigade level by experienced staff officers, who updated Allenby’s officers regarding current trends and tactics. These lectures were followed by tactical demonstrations and conferences. Allenby himself visited his divisions and also held conferences to ensure that every bit of practical information was reaching his soldiers. He also ordered mock Ottoman trenches to be constructed, which would allow his soldiers to rehearse combat operations before an attack. Allenby was very aware of contemporary British tactical thought and ordered his companies to begin combined-arms training in open warfare tactics, thus bringing the infantry together with artillery, machine guns and engineers.

A group of Turkish prisoners. Although unkempt and motley in appearance, these Ottoman POWs retain much of their military bearing. This reflects the Spartan-like discipline of the army and its training regimes.

In August 1918, the Yildirim Army Group had 12 understrength divisions available for the defence of a 90km (56-mile) front. The Ottoman Amy in Palestine had grown progressively weaker over the course of the year. This was a combination of losses (which had never been replaced), inadequate numbers of replacement soldiers and a higher than normal rate of desertion. By mid-summer, morale in the Ottoman divisions was at an all-time low, and supplies of all types were very limited. Moreover, many of the Arab conscripts were enthused with the idea of Arab nationalism and willingly deserted to the British. The strength of some infantry divisions dropped to a front-line rifle strength of 2000 men. Even in the army’s premier divisions (such as the 19th Infantry Division) infantry battalions, which at Beersheba had numbered 600 men, now numbered 200 men or less. Some regiments tried to keep a company at full strength, but this affected the remaining companies.

To make matters worse for the regular infantry establishment, the Ottoman Army in 1917 began to form assault battalions modelled on German stormtroops. The best officers and the most fit and aggressive soldiers were selected for these units and then sent to intensive battle training courses. Several of the assault battalions saw active service during the battles along the Jordan River in April. Although the need for such a specialized offensive capability had passed, the Turks retained their assault battalions in most of their divisions in Palestine. This practice concentrated the cream of the divisional infantry strength into a single battalion and had the effect of weakening the regular line infantry battalions. Exaggerating the situation, the flow of replacements and recruits dried up in the summer of 1918 and the line infantry regiments received men who were mostly deserters or criminals from the empire’s jails, hardly the most promising raw recruits to replace combat losses. This situation greatly reduced the effectiveness of Liman von Sanders’s army.

Indian lancers bringing in Turkish prisoners, Jericho, 15 July 1918. Over half of Allenby’s cavalry force was composed of Indian Army regiments. He would unleash them at the Battle of Megiddo on the Turkish rear.

According to late 1918 Ottoman Army doctrine, Liman von Sanders should have had 18 divisions in the line to defend his 90km (56-mile) front, plus an additional seven divisions in a deeply layered arrangement of reserves. Of course, these templates were based on full-strength Ottoman divisions numbering some 12,000 men; Liman von Sanders’s divisions operated at about a sixth of that number. In reality, the Yildirim Army was attempting to hold the front with about 15 per cent of the troops required by the army’s tactical doctrine.

Allenby intended to inflict a decisive defeat on the Turks at the strategic level. His plan was the reverse of the Gaza–Beersheba plan of 1917. Instead of feigning to attack near the sea and attacking inland at Beersheba, in 1918 Allenby chose a feint near the Jordan River (scene of his spring and summer offensives) and then to smash his way through the Turkish defences on a narrow avenue next to the sea. Achieving a breakthrough, Allenby intended to pass his cavalry corps through the breach and rupture the Turks’ lines of communications. This accomplished, Allenby would envelop the remaining Turkish forces. Probably the best-known aspect of his plan was the attention paid to an elaborate deception scheme encouraging the Turks to believe that he intended to strike his main blow along the Jordan River front. Allenby’s intelligence staff sent out phantom wireless units, constructed elaborate dummy positions and moved small numbers of troops frequently, all of which were designed to make the enemy think that the EEF was massing for a main effort in the east. Particular attention was given to aerial superiority operations that denied the Turks and the Germans the opportunity to conduct aerial reconnaissance over the British lines. Importantly, Allenby’s new plan was different from his previous ones in that he called for the destruction of the enemy army by disruption and envelopment rather than for the occupation of important geographic features, foreshadowing the blitzkrieg operations of World War II.

At the tactical and operational level the EEF developed very sophisticated plans that focused on the coordinated use of artillery in support of the infantry. A short creeping barrage was planned for the divisional artillery while counterbattery targets were selected and registered for the corps artillery (two-thirds of the heavy guns were allocated to this task). Senior commanders, who in the past had remained well behind the lines, were brought forward to closely control operations. Detailed coordination instructions and rehearsals were drawn up to ensure that the exploitation force of cavalry would be able to execute the difficult task of the passage of lines through the infantry. The infantry was trained to move forward bypassing strong points of resistance. Finally, procedures for close air support were developed and plans laid for aircraft to support the cavalry with deep raids into enemy territory. Overall the EEF’s mature plan of operations mirrored the latest tactical techniques that the BEF had used at Amiens in August (minus, of course, the tanks).

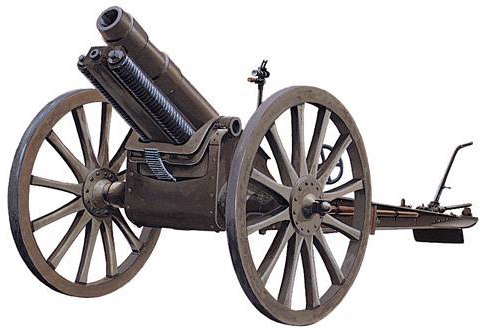

120mm Krupp Howitzer M1905, in Turkish service. The Ottomans increased their artillery inventory as the war progressed. By the end of 1918 the Germans had sent the Turks 559 artillery pieces of various calibres.

Liman von Sanders, on the other hand, had no real plans at the strategic or operational level other than a determination to hold every inch of ground. This was not a function of his tactical belief but reflected the relative immobility of his army. Indeed, by the summer of 1918, the Ottoman Army in Palestine did not have enough draft animals to transport its artillery, ammunitions and supplies. The animals on hand, moreover, were weakened by inadequate quantities of fodder and grain, which made their usefulness as draft animals problematic. While the infantry retained some measure of tactical mobility, the rest of Liman von Sanders’s army was almost incapable of movement. The result of this was that the army was ordered to fight for every position. The few reserves that were available were small in number and were controlled at corps and divisional level. Once the battle began, Liman von Sanders had almost nothing with which to influence the battle.

A Turkish VIII Army Corps camp. This photograph was probably taken during pre-war manoeuvres and reflects the professionalism that the army was capable of when it could put its best foot forward.

This situation made it imperative for the Yildirim Army’s staff to predict where Allenby might strike his main blow. While the extant historiography maintains that Allenby achieved complete surprise, the Turkish record indicates that this is untrue. In fact, several days before the attack, both Cevat Pasha and Mustafa Kemal requested permission to withdraw to a more defensible position 20km (12.4 miles) to the rear because they believed an attack was imminent. The Turks concentrated their best divisions in the threatened coastal sector and these were supported by the bulk of the army’s heavy artillery. Liman von Sanders’s only large reserve formation was also positioned directly behind the Ottoman XXII Corps, which held the coastal sector. Finally it must be noted that the front-line Ottoman regiments were warned several days in advance of the impending attack. Moreover, no Ottoman Army reserves were drawn to the Jordan River valley, thus nullifying the elaborate deception measures.

Cevat’s Eighth Army defended the coast with XXII Corps (the 7th and 20th divisions) and the Left-Wing Group, a corps-sized formation commanded by German Colonel von Oppen (the 16th and 19th divisions and the German Asia Corps). The line continued eastward with Seventh Army (of which Mustafa Kemal took command on 17 August) consisting of III Corps (1st and 11th divisions) and XX Corps (26th and 53rd divisions). The Fourth Army defended the Jordan front with VIII Corps (48th Division and several provisional divisions), the Sheria Group (3rd Cavalry Division and 24th Division), and II Corps (62nd Division). By early September 1918, the evidence of an impending British offensive was undeniable, and Liman von Sanders maintained his best forces in the coastal plain. Consequently, although the Yildirim Army Group remained spread along the entire front in static defensive positions, it managed to concentrate in the threatened sector.

British artillery in action. By the standards of the Western Front, artillery combat in the Middle East was all but derisory. Barrages were of short duration, and ammunition expenditure numbered in the tens of thousands of projectiles rather than in millions.

Allenby concentrated four full-strength infantry divisions (the 60th and 75th divisions and 3rd and 7th Indian divisions) on a front of about 12km (7.5 miles) opposite the Ottoman XXII Corps. Unlike the nine-battalion British divisions then fighting in France, Allenby’s EEF divisions maintained the 12-battalion organization. Altogether he planned to throw 24,000 infantrymen supported by over 40 guns against XXII Corps (a further 8000 infantrymen lay in immediate reserve). Poised directly behind this were the 4th and 5th Cavalry Divisions and the Australian Mounted Division. Opposing this force were some 3000 Turks in the trenches of XXII Corps supported by about a hundred guns (a further 5000 Turks were assigned to Oppen and in reserve).

The British offensive began with the Arabs and Colonel T.E. Lawrence conducting raids cutting the railway between Dera and Amman on 16 September. On 17 and 18 September the British XX Corps began a diversionary attack in the centre of the Turkish front. These operations were designed to fix the Turks in place and to deceive them as to the true location of the main attack. The main attack began at 4.30am on 19 September 1918, with a short bombardment followed by a creeping barrage that screened the advancing British infantry. Turkish resistance was sporadic and uneven along the front. In most places Allenby’s Indians and British overran the enemy trenches in a very short time. The attacking troops used the most current British fighting methods, including the bypassing of enemy strongpoints.

Because of Liman von Sanders’s tactical guidance, the Turks prepared to fight to the death for their positions. Initially, very heavy British artillery fire pounded the front-line positions of the regiments of the 7th and 20th divisions. Allenby’s tactics mirrored those in France and the bombardments were relatively brief. Then, as the infantry came forward, the artillery shifted its fire to conduct a creeping barrage in front of the assaulting troops. These creeping barrages were timed to shift the curtain of fire closer to the enemy every couple of minutes, with the infantry following about 75m (82 yards) behind the bursting shells. It was dangerous, but it kept the Turks off their machine guns long enough for the British and Indians to close with the enemy trenches. By 5am, the British artillery firing had ceased and by 5.50am all local Turkish reserves had been committed to the fight. Reports indicating an imminent collapse poured into the Turkish XXII Corps Headquarters.

By 7am, the British had broken cleanly through the Turkish defences and were waiting to pass the cavalry through the breach into the Turkish rear. The first real reports about the conditions in the breakthrough area reached Liman von Sanders at 8.50am from the Eighth Army, indicating that the 7th Division was all but destroyed and the situation was very bad. Additionally, the XXII Corps artillery had been lost. The army also reported that the adjacent 19th Division was now under heavy attack. The report ended with an urgent request for assistance. Liman von Sanders responded immediately, sending his few available reserves (an infantry regiment and some army engineers) forward to help the Eighth Army. It was too little too late. By 10am, the British had passed two entire cavalry divisions through the huge hole blown open in the Turkish defences. These cavalry divisions were ordered to ride hard and straight towards the Turkish rear. The cavalry were assigned deep objectives, including the towns of Nazareth (containing Liman von Sanders’s headquarters) and Megiddo, and the northern exits of the Plain of Esdraelon. It was hoped that the cavalry would be able to capture Liman von Sanders himself.

Lawrence has achieved wide contemporary notice as a prophet of the tactics of insurgency. However, modern Turkish histories show that the Ottoman Army was able to deal with the mobile Arab rebel armies by largely ignoring them. Lawrence’s bands raided isolated outposts and, more frequently, destroyed the Ottoman railway line to Medina. These losses were pinpricks to the Turks and the broken rail lines were easily repaired within days of their destruction. Even in the final campaigns in Syria the Turks deployed few military assets against the Arabs. Moreover, they never worried about an actual Arab uprising behind their lines as the rebels had little interaction with the civilian population in either Syria or Palestine. On the British side, Allenby was often disappointed by the Arab failure to assist him on his right flank. As a matter of record the Arab Revolt was never a movement that was broadly supported by the Arab population. While associated with guerrilla warfare and insurgency, in truth the glamorous Lawrence was more of a practitioner of what might be termed ‘irregular warfare’.

The Battle of Megiddo and the pursuit to Damascus, 19 September–8 October 1918. Liman von Sanders had almost no reserves behind the Megiddo line. When Allenby’s infantry ruptured the Ottoman lines, it led to one of history’s greatest cavalry exploitation and pursuit operations.

Reports from the centre and the left wing began arriving at Liman von Sanders’s headquarters early, but ceased almost entirely later in the day. He interpreted the devastating news correctly: his right wing was destroyed and his flank exposed. He reacted promptly and ordered the Seventh Army to begin withdrawing to the north in order to prevent the British from conducting a short envelopment to the Jordan River. Liman hoped that the Fourth Army might hold firm and provide a solid anchor for his rapidly disappearing army. The next day Allenby’s cavalry took Nazareth, almost capturing the surprised Liman von Sanders in bed early in the morning. The following day the British and Indian cavalry reached the shores of the Sea of Galilee and the upper Jordan River. Unlike in previous battles, the Ottoman Army in Palestine disintegrated. For all practical purposes, the Turkish XXII Corps and its divisions was destroyed in two days. On 21 September the Eighth Army itself ceased to exist and its commander, Cevat Pasha, fled to the safety of Mustafa Kemal’s headquarters.

It was an impossible strategic and operational situation for Liman von Sanders, who was totally incapable of preventing Allenby from destroying his army piecemeal. From 21 to 23 September, the famous Ottoman III Corps fought a gallant rearguard action from Tubas to the Jordan River. This allowed the Turks to block the developing British encirclement. Together, these units bought enough time for the surviving units to pull back behind the Jordan River. By 25 September, the coastal cities of Haifa and Acre had fallen, as had Megiddo. By 27 September, the relentless cavalry had broken the Jordan River line and pushed the Turks back towards Dera. The British had now entered Syria and the Battle of Megiddo, or the Nablus Plain as the Turks call it – in reality a series of battles within a campaign – finally ended.

In spite of the great victories in Armenia and in Azerbaijan, it was now apparent to all but the most diehard nationalists in the Turkish General Staff that Turkey was now in an indefensible condition, which could not be remedied with the resources on hand. It was also apparent that the disintegration of the Bulgarian Army at Salonika and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Army spelled disaster and defeat for the Central Powers. From now until the armistice, the focus of Turkish strategy would be to retain as much territory as possible.

Serving rations to Turkish troops in the desert. Ottoman soldiers were authorized rations in the amount of 3149 calories per day, including 600g of bread and 250g of meat. To receive even half of this amount was a rarity for them.

‘The army will attack with the intent of inflicting a decisive defeat on the enemy and driving him from the line.’

General Sir Edmund Allenby, Force Order 68, 1918

Liman von Sanders’s defeat was inevitable. First, the terrain was favourable for the attack, at least in comparison with Gallipoli or Caucasia. Second, there was room for Allenby to shift corps-size formations around the battlefield to achieve deception and concentration. Third, and without doubt most importantly, the British Army had made significant and effective changes in its fighting methods and tactical doctrines in 1918. It is doubtful whether Liman von Sanders entirely grasped how quickly, and in which ways, the British Army had changed. In truth, his plans might have prevailed against the tactically clumsy British Army of 1915, but not against the highly mobile army of 1918.

Whether the outcome of these battles would have been different had Falkenhayn’s ideas about a flexible defence been retained will never be known. However, it is likely that a more flexible Turkish defence would not have resulted in the total destruction of division-level Turkish formations. The British would have advanced in any case, but the orderly fall back of the infantry divisions on the coastal plain might have prevented the ruptured lines that enabled the great British cavalry breakthrough, which led to the annihilation of the Eighth Army.

Aerial operations reached their high point in the Middle East with Allenby’s offensive at Megiddo. By 1918 substantial numbers of aircraft had made their way to the theatre, although not in the huge numbers then seen in France. Allenby had organized his airmen into the Palestine Brigade, Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and expanded it as more aircraft and pilots arrived. He used it at Third Gaza primarily to destroy Kress’s aircraft on their airfields in an attempt to deny him the use of air assets. As the campaign developed, Allenby’s airmen became very proficient in their jobs. Of particular note was the rapidly developing capability in aerial photography, which mapped almost every square inch of Palestine. This was linked to a very effective mapping service that, in turn, produced high-resolution tactical maps for the army. As the war entered 1918, ‘The army will attack with the intent of inflicting a decisive defeat on the enemy and driving him from the line.’ Britain’s highly efficient aircraft industry enabled the air staff to send the latest aircraft to Palestine, including DH-9s, Bristol Fighters and SE-5as. This gave Allenby an edge in quality and quantity over the Germans and Turks.

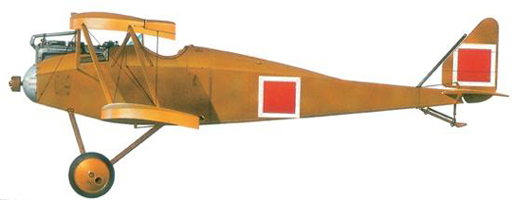

For their part, the Turks languished at the end of a long and problematic logistical chain that reached through Anatolia and the Balkans to Germany. The Turkish air service was entirely reliant on German military assistance packages to provide aircraft and spare parts. By 1918, most of their available air squadrons were deployed to Palestine and Gallipoli, but these were under-equipped and poorly manned. However, the Germans also sent four active air squadrons to Palestine under the terms of the Yildirim Agreement’s protocols (Flieger Abteilung 301–304), which were popularly called the ‘Pasha squadrons’. These aircraft were very valuable to Liman von Sanders, who came to rely on them for reconnaissance and aerial mapping. Unfortunately for the Ottomans their numbers were too small to allow them to be used to a great extent in active combat missions against enemy ground forces. Importantly, by 1918 most of the Turco-German squadrons were equipped with aircraft (Albatros D.IIIs, for example) that were a generation behind the most current the British employed in Allenby’s squadrons.

The air campaign waged in support of Allenby’s offensive at Megiddo ranks as one of the most important factors in his victory. In a carefully orchestrated campaign, the Palestine Brigade established air superiority in September 1918 to deny the Turks the opportunity to conduct reconnaissance flights over the British lines. This had the effect of blinding Liman von Sanders as to the locations of British troop concentrations and movements, enabling any attacks to achieve complete surprise. Allenby’s airmen then prepared a carefully crafted plan that located the key defiles, road junctions, enemy headquarters and communications centres, and then targeted them for destruction. Communications procedures were developed, including radio, flares and dropped messages that enabled Royal Flying Corps liaison officers accompanying the leading cavalry detachments to communicate directly with aircraft overhead.

On 21 September 1918, Allenby’s air chief, Sir John Salmond, unleashed his airmen on the Turkish rear areas. While Allenby’s artillery supported his attacking infantry, Allied aircraft prepared the way for Allenby’s cavalry. The Turkish telephone exchanges were quickly knocked out and enemy headquarters were attacked as well. Missions were flown against enemy reserves, road junctions and logistics sites. Additionally, a counter air campaign was successfully waged against the enemy’s airfields to keep the Turkish and German aircraft pinned to the ground. With almost no situational or spatial awareness and confronted with the massive disruptions caused by attacking aircraft, the Turks were unable to mount a coherent defence. When Allenby’s cavalry began its great drive into the Turkish rear, it was supported by aircraft that provided immediate intelligence on enemy locations. It was a brilliant and effective effort by a thoroughly professional air–ground team.

An air reconnaissance photo taken over Jerusalem. Allenby’s Royal Air Force squadrons brought the art of aerial photography to a high level. As a result his army enjoyed superb maps and real-time intelligence.

Probably the most famous and best-known event of the air campaign came on 21 September 1918, when Australian airmen caught the retreating Ottoman Seventh Army in the Wadi el-Far’a defile. In this narrow chokepoint, the Australians of No. 1 Squadron found the Turks unsupported by either friendly aircraft or anti-aircraft guns and conducted carefully orchestrated aerial attacks coordinated by wireless with six aircraft arriving to bomb and strafe the Turks every half hour. Thousands of men and animals died in these attacks. After the battle, the ground forces counted over a hundred cannon, 59 motor lorries and over 900 horse-drawn wagon and carts in the defile.

A German Halberstadt D.IV, fighter biplane in Turkish service. The Germans sent over 300 aircraft to the Turks during four years of war. Most of these were two-seater reconnaissance or fighter aircraft.

Liman von Sanders and his commanders fought to keep the Ottoman armies intact. Allenby, however, maintained relentless pressure and ordered his fast-moving and powerful cavalry to seize Damascus. Liman von Sanders shifted some of his few remaining combat formations northwards to deal with this threat and assembled the 24th, 26th and 53rd divisions and the 3rd Cavalry Division under the command of III Corps for the defence of the city. However, these units were badly worn down by combat and retreat, and could not hold Damascus, which fell on 1 October 1918. The 3rd Cavalry Division was destroyed in a desperate rearguard action, which allowed the remainder of the Turkish forces to escape northwards.

The Handley Page O/400, a British heavy bomber biplane. The Handley Page O/400 first entered service in March 1917, and was used primarily on the Western Front, but also saw limited service in Palestine.

An impossible strategic situation confronted Liman von Sanders in early October 1918. The Eighth Army had been destroyed and its headquarters captured. III Corps, with the 1st and 11th divisions, was still intact and conducting a fighting retreat, as was XX Corps, and the 48th Division. Many of these divisions were very short of cannon as the Yildirim Army Group had lost most of its artillery. In early October, the 43rd Division arrived as reinforcement but was immediately committed to the defence of Beirut. The British tempo was unrelenting, and they took Beirut on 8 October. On 16 October, the Fourth Army headquarters was encircled and destroyed in the city of Humus. The 48th Division attempted to set up blocking positions at Hama, south of Aleppo, but lost the city on 19 October. On 25 October, Allenby’s army entered Aleppo. Almost simultaneously, Lawrence and Faisal Hussein arrived in Damascus in an attempt to establish an independent Arab presence in Syria. The campaign for Lebanon and Syria lasted a month.

On 26 October 1918, Liman von Sanders’s headquarters fell back to the Anatolian city of Adana. The army still had combat capability with the 23rd Division at Tarsus and XV Corps in Osmaniye (41st and 44th divisions). Mustafa Kemal’s Seventh Army was located in Raco with III Corps at Alexandretta (11th and 24th divisions), and XX Corps near Katma (1st and 43rd divisions). While badly worn down, Liman von Sanders prepared his army for a final defence of the Ottoman heartland.

The Allied entry into in the Hedjaz. The Turkish force present there, out of communications with the homeland, held out until after the signing of the Mudros armistice.

The Allied entry into Damascus. After Megiddo the Turks tried to fight a delaying action back to Damascus. Allenby’s cavalry constantly outflanked them and rode them down. The city fell on 1 October 1918.

At the armistice, the newly installed Turkish Minister of War, Ahmet Izzet Pasha, recalled Liman von Sanders to Constantinople on 30 October 1918. In his place Mustafa Kemal was appointed to command the Yildirim Army Group, and he reported for duty the next day. Liman von Sanders’s farewell message to his armies praised the Ottoman performance at Ariburnu and Anafarta (in Gallipoli) and in Palestine. He expressed how proud he was to command Ottoman forces from the first time he set foot in Turkey, and he thanked the Turks for their hospitality. The tireless Mustafa Kemal immediately began to energize the defence of the Anatolian heartland.

It is uncertain today how many casualties the Ottoman armies sustained in these campaigns. General Wavell, in his biography of Allenby, states that the British took 75,000 prisoners and 360 guns in the six-week campaign from 18 September to 31 October. Indeed, the Turkish official history of the campaign quotes these British figures, possibly as a result of the loss of records caused by the destruction of the Fourth and the Eighth Army headquarters. The cost to the British was about 6000 men. Allenby’s lop-sided victory was one of the most complete in a war that was almost bereft of such achievements. However, the Ottoman Army was still in the field and actively preparing its defence of southeastern Anatolia when the armistice was signed. Further British operations in the winter of 1918 would have come up against determined men under Mustafa Kemal in mountainous terrain.

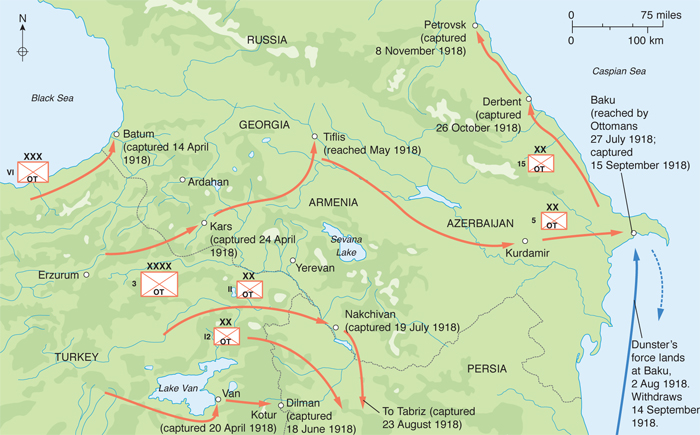

From May 1917, the Caucasian front was quiet as the Turks enjoyed a Russian strategic pause. On the Russian side, war weariness and the effects of the revolution continually eroded troop morale. They maintained four army corps guarding their conquests in Anatolia, but none were in any condition to fight. In a sense, the Russian army in the Caucasus ‘self-demobilized’ in the autumn of 1917 as troop strength evaporated. As the Russians withdrew the remnants of their army, a loosely organized federation composed of the newly independent states of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia was left behind to face the Turks. Unfortunately for these peoples, the Russians were focused on salvaging their nation from the grasping German negotiators at the ongoing peace talks at Brest-Litovsk. None of the infant Caucasian republics were represented at the peace table, nor did the Russians evince any interest in ensuring their safety. In January 1918, when the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk came into effect, the continued existence of these states was not guaranteed, nor were the Turks obliged to honour their territorial integrity. This created a serious power vacuum in the Caucasus, and although these new states had small armies, they were not nearly as powerful as the Ottoman forces that remained in the region.

As the Russians reduced their armies in the Caucasus, the Turks were also able to draw down their Caucasian armies as well. The Caucasian Army Group was inactivated on 16 December 1917 with the unlucky Second Army soon following. The IV Corps, with the 5th and 12th Infantry divisions, was absorbed into the Third Army, which assumed the frontage and the responsibilities of the inactivated Second Army. The Third Army commander, Vehip Pasha, had carefully husbanded the strength of his army for more than a year. His creative reorganization of his army into what he styled ‘Caucasian corps’ and ‘Caucasian divisions’ was successfully completed during the previous year (in reality these were merely reduced-strength divisions), and the rebuilt units were rested and combat ready. Indeed, having no significant or active enemy opposing it, the general staff requested that Vehip send some of his infantry divisions to more active fronts. Vehip, however, successfully fended off most of these requests, losing only the 2nd Caucasian Cavalry Division to the Palestine front. Vehip’s army was actually very weak, which was reflected in his strength returns. On 1 January 1918, the total strength of the combined I and II Caucasian corps was 20,026 men, 186 machine guns and 151 artillery pieces – a total barely exceeding the combat strength of a single British infantry division fighting on the Western Front. The I Caucasian Corps on 11 February 1918 reported about 12,000 soldiers present for duty. Additionally, the corps returns showed a total of only 98 machine guns and 46 artillery pieces present on the same date. Under most circumstances, the Ottoman Third Army would be considered incapable of offensive action.

Members of the Army of Islam operating a heavy mortar in 1918. The Caucasus front in 1918 was the single bright spot in the Ottoman war effort. The Army of Islam captured the oil port of Baku on the Caspian Sea on 15 September 1918.

However, throughout 1917 Enver Pasha had been watching the situation in the Caucasus, and in December he seized on a tactical report from the Third Army written by a Captain Hüsamettin stating that the Russians were incapable of maintaining the front for very much longer. Enver was also alarmed by Third Army reports of British and French involvement in the Tiflis region and by the formation of large Armenian and Greek military units. Furthermore, there were rumours of massacres of Muslim Turks and Azerbaijanis by Armenians. Ottoman intelligence had also received information that Armenian Dashnak committees were preparing to establish a breakaway republic centred on Erzurum in the Caucasus.

After analyzing these reports, Enver Pasha and the Ottoman general staff began to consider the possibilities of a renewed offensive in the Caucasus, one that would reclaim the frontiers lost in 1877. Enver decided to reinforce Vehip’s army and issued official orders to the Third Army on 23 January 1918 to begin planning and preparations for offensive operations. The 15th Infantry Division (recently returned from operations in Romania), 120 motor driven trucks, three Jandarma battalions and the full-strength 123rd Infantry Regiment were earmarked for service with the Third Army. These forces were put on fast steamers on 9 February, and they began to arrive in the small Black Sea port of Giresun three days later (the Russian Navy, by now, being reduced to inactivity).

Kress and German staff officers attending a funeral in Georgia. The Germans were furious at Ottoman attempts to invade Georgia in violation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. They sent troops there to oppose the Turks, thereby ensuring the survival of the Georgian Republic.

As the Third Army was brought to a condition of combat readiness, the I and II Caucasian corps received orders assigning them objectives deep within the territory occupied by both the Russians and the Armenians. In concept, the plan envisioned a three-pronged drive into Russian-held territory. The II Caucasian Corps would drive along the northern Black Sea coast, with the 37th Division, to reclaim Trabzon. The I Caucasian Corps would seize Erzincan and then drive on towards Erzurum. The IV Corps received orders to seize Malazgirt.

Opposing the Third Army was an Armenian army of about 50,000 men, equipped mostly with cast-off Russian equipment. They were organized into two rifle divisions, three brigades of Armenian volunteers, and a cavalry brigade. The rifle divisions were made up of veteran soldiers from the Druzhiny units, which had fought alongside the Russians for almost four years. These were augmented by volunteers from the surviving local Armenian populations of Erzurum, Van and the Eliskirt Valley. The Armenian National Army (as it was called) was actually well equipped, since it was allowed to recover the best of the equipment left behind by the departing Russians. The definitive Western history of the Caucasian campaign reported that the combat strength of the Armenian National Army did not exceed 16,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry and 4000 volunteers. These small numbers of Armenians were greatly outnumbered by Vehip’s Third Army.

On the morning of 12 February 1918, Vehip’s troops went forward. Erzincan was seized in short order and with it the Turks took tons of supplies, artillery pieces and large quantities of munitions. The Armenian population in the area began immediately to flee towards the east, while the Armenian Army began a delaying retreat towards the rear. The Turks retook the important Black Sea port of Trabzon on 25 February and sea-borne reinforcements immediately began to debark.

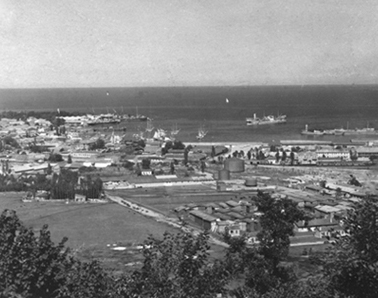

A view of the port of Batum from the city’s fort. The collapse of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in 1918 enabled the Ottoman Navy to conduct operations in the Black Sea with impunity.

Despite adverse weather and occasional Armenian resistance, Vehip Pasha urged his troops forward. The Armenians attempted to hold the fortress of Erzurum, but after several days of fighting I Caucasian Corps reclaimed the city on 12 March. There they discovered that the retreating Armenians had massacred many Muslim inhabitants in retaliation for the massacres inflicted on the Armenians in 1915. By 25 March, the Turks were advancing across the entire front.

Vehip reorganized his army in April 1918 to configure it for offensive operations deep in the Caucasus. He formed what would be called in modern terminology an ‘operational manoeuvre group’ by transforming II Caucasian Corps into a Group Command. Under this new command, Vehip assigned the entire I Caucasian Corps and 5th Caucasian Infantry Division. Reinforcements arrived in the form of VI Corps Headquarters (from Romania), brought by fast steamers to the Third Army. In the centre the new group was ordered to drive on Kars (lost to the Russians in 1878) while VI Corps would drive along the coast toward Batum. To the south IV Corps would liberate Van and Bayazit. The scope of the operation was ambitious, and it was a remarkable undertaking to reorganize the entire command structure on such a short and unannounced basis. In spite of potential problems, the Turkish commanders moved ahead and made it work.

Vehip’s troops took the city of Sarikamis on 5 April, avenging the defeat of 1914, and then began advancing on Kars. The long-held city of Van was liberated on 6 April and Dogubeyazit fell on 14 April. The IV Corps continued its attack and took the frontier town of Saray. However, it did not stop, and drove into Persia, taking Kotur (last held in the spring of 1915 by the Van Jandarma Division) on 20 April 1918.

Along the coast, Armenians and local Greeks attempted to defend Batum, but VI Corps’ attacks pushed them back and Batum fell on 14 April 1918. Again, the Turks captured quantities of war material, particularly much-needed transport including two locomotives, cars and wagons. In the coastal regions, the Turks also discovered many Muslim villages that were reduced to piles of burnt debris, their residents now nothing more than dismembered corpses. The Turks attributed these atrocities to the local Christian inhabitants rather than to the Russians.

Russian naval cadets in Batum. The Turks lost Batum to the Russians in 1878, but briefly held it again in 1918. The port reverted to Soviet control shortly after the Turkish withdrawal from the Caucasus.

In the centre, the Armenians attempted to hold the fortress city of Kars, which had fallen to the Russians in 1878. The Russians had heavily fortified the city and turned the defences over to the Armenians intact. It was defended by 10,000 Armenians and the fortress contained over 200 artillery pieces.

The Turks advanced on the city in early April 1918. By 24 April they had almost encircled Kars and laid siege to it. It was clear to all concerned that Vehip had the means and the determination to take the city and the Armenian leaders frantically tried to negotiate a truce. Vehip demanded the surrender of the fortress intact as the price for a peaceful withdrawal, and the Armenians had no choice but to accept. The following morning the Turks entered the intact fortress of Kars with its abundant storehouse of supplies and large quantities of weapons. The artillery park was captured in its entirety and added significant combat power to the Turkish Army. Vehip’s men continued eastwards, and by the end of April 1918 the Third Army had arrived at the old 1877 frontier.

Turkish offensive operations continued into May 1918 with IV Corps pushing deeper into Persia from Dogubeyazit and taking the city of Moko. Vehip then pushed beyond the 1877 frontier on a broad front, conducting offensive operations along the railway line towards the Caucasian city of Tiflis. The political situation continued to deteriorate and became very confusing. The Turks, Russians and delegates from the Trans-Caucasian Federation had been trying to reach an agreement since 23 February, at a conference in the port city of Trabzon. The Russians were hoping for an end to Turkish expansion into the Caucasus while the Georgians, Azeris and Armenians sought to gain legitimacy for their fledgling national states. In the middle of these negotiations, Georgian nationalists in Tiflis proclaimed the complete independence of the Trans-Caucasian Federated Republic. Soon afterwards, the new state proclaimed its commitment to a continued state of war with the Ottoman Empire, and the Trabzon talks collapsed.

Russian soldiers photographed at Tabriz. The Russian occupation of parts of Persia was short lived, as the army dissolved in the chaotic aftermath of the revolution.

Peace discussions resumed in Batum on 11 May 1918, but Vehip Pasha simply issued an ultimatum demanding the occupation of much of what is now Georgia. While the delegates bickered, the Third Army continued its relentless advance.

The Germans were particularly bothered by the Turkish demands and were not at all happy with the continuing Turkish drive into former Russian territory (they regarded Ottoman expansion into the Caucasus as a serious violation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk). Unfortunately for the Germans, alliance politics required the maintenance of effective relations with the Turks, and the Germans resorted to devious methods to stop the Turkish incursions. Colonel Kress von Kressenstein, having been released from his assignment commanding the Turkish Eighth Army, was sent to Tiflis, along with German diplomat Count von Schulenberg. These two Germans hastily conferred with the alarmed leaders of the Trans-Caucasian Federated Republic to arrive at an unusual yet enormously creative solution to the problem.

Troops in the Caucasus 1918. The identity of these men is unclear, but with their signature heavy personal arms and ammunition bandoliers, they are probably Armenian.

On 27 May, the Georgian members of the republic announced the creation of a separate Georgian state. Simultaneously, Kress and Schulenberg announced the creation of a German protectorate for the newly independent Georgian state. The Turks were furious, with Vehip calling for an immediate invasion of Georgia. Almost immediately signs of German influence appeared in Georgia, with German and Georgian flags flying together everywhere. The German Army even sent some companies of infantry by sea from the Crimea to the Georgian port of Poti. Alarmed by the growing rift between the allies, Enver Pasha and his new chief of staff, German General Hans von Seeckt, went to Batum for discussions aimed at easing the tensions. Conceding to German pressure, the northward expansion of the Turks into Georgia was temporarily halted.

However, Enver refused to relinquish his cherished dream of a pan-Turanic empire and once again reformed his Caucasian forces. From the units of the Third Army, Enver formed a new Ninth Army. To coordinate the activities of these two armies, Enver formed the new Eastern Army Group commanded by Vehip. In orders issued to all formations on 8 June 1918, Enver now reoriented the strategic direction of his Caucasian forces to the east and to the south, towards Azerbaijan and Persia. The new command structure of the Eastern Army Group accommodated this change in strategic direction by establishing two separate armies, which could operate on a wide front, with new missions and objectives. The Ninth Army was directed to attack into Persia and to seize Tabriz. The Third Army was directed to continue the drive eastwards towards the Caspian Sea. The Third Army staff hurried to move troops and equipment around the theatre to support the new command structure.

On 29 June, Enver ordered Vehip home to Constantinople and directed Halil Pasha, the hero of Kut and commander of Sixth Army, from Mosul to replace him as the commander of the Eastern Army Group. By mid-June 1918, the Third Army was making good progress, with a renewed advance eastwards along twin axes towards Baku. The Armenians and Azeris counterattacked the advancing Turkish columns and attempted to establish a defensive line in the vicinity of Kurdamir. However, Halil’s 5th Division pushed onward towards Baku, and by 27 July occupied positions overlooking the city.

The rest of the Third Army laboured to catch up with the 5th Division’s swift movements and there was a temporary lull in the tempo of operations. In July 1918, Enver began to put together the idea of an ‘Army of Islam’. Built around a hard core of Turkish divisions, this force would mobilize Islamic supporters and sweep down through Persia to retake the Shatt al-Arab, where it would trap the British forces in Mesopotamia. Enver’s agents went to work to establish ties with and support from the Pahlevi family in Persia. On 10 July 1918, Enver activated the new Army of Islam (composed only of the 5th Caucasian Infantry Division and the 15th Division and some independent regiments).

One of the more interesting vignettes of World War I occurred as the Turks conquered Azerbaijan and approached Baku. In early January 1918, the British became concerned about Turkish inroads into the Caucasus and, in particular, about a possible threat to British interests in Persia. Consequently, they decided to send an expedition to Baku. Major-General L.C. Dunsterville, who was a boyhood friend of Rudyard Kipling and the model for ‘Stalky’ of Kipling’s ‘Stalky and Co.’, was appointed to lead an armed military mission to the Caucasus. Dunsterville began organizing his expedition, now called ‘Dunsterforce’, at Baghdad in the spring of 1918. His rather fuzzy mission was to proceed into Persia and enter the Caucasus via the Caspian Sea. Typically, Dunsterville was well supplied with money and advice but was short of troops and equipment. By mid-February he had reached Enzeli on the Caspian coast and there he formed a small army of Cossacks, Russians and Azeris. These men were not particularly reliable and Dunsterville narrowly escaped ambush several times, finally retiring to Hamadan. There, he began training his ragtag army with British officers and NCOs and awaited events as they unfolded in Enzeli. Because of the developing Ottoman threat to the Baku oil fields, the British began to send reinforcements to Dunsterville in June 1918. Dunsterville then began to fight his way back to Enzeli, where he could coordinate future combined operations with Bicherakov’s Cossacks. By early July, Dunsterville had built a small flotilla on the Caspian and landed the Cossacks at Alyat. Encouraged by this he began to land the main body of Dunsterforce on 2 August in Baku.

Georgian troops. German occupation and assistance assured the preservation of Georgian independence for a brief time. Soviet forces took control of the republic when the Germans returned home at war’s end.

The Ottoman advance to Baku and Petrovsk in mid to late 1918 demonstrated that, despite massive casualties, their army still retained combat effectiveness and cohesion at this late date in the war.

Baku’s rich and productive oil fields became a strategic objective for British, Ottoman and Soviet forces in 1918. Ultimately, the Soviets regained control of them.

In the meantime, the Army of Islam started its attack on the city on 31 July. Several serious assaults were waged over the following week, but the Azeris and Armenians held firm. Reinforcements arrived and Halil prepared to renew the attacks. However, he received the first reports that 300 British soldiers had arrived in Baku on 5 August and that a further 5000 were awaiting transportation in Enzeli. Halil’s worried staff now thought that they would need an additional 5000 fresh troops and several batteries of heavy artillery to take Baku. By 17 August, Dunsterforce had three battalions of British infantry, some field artillery and three armoured cars in Baku. However, Dunsterville was becoming more discouraged every day as the Azeri and Armenian defence force began to fall apart from the lack of dynamic leadership. Halil began to plan for the final assault on Baku, with the 15th Division coming in from the north and the 5th Caucasian Infantry Division attacking from the west. The attacks began at 1am on 14 September 1918 and the Turks made rapid progress against crumbling defences. The disenchanted Dunsterville was ready and had planned a withdrawal reminiscent of the Gallipoli evacuation. He quickly recognized that the defence was failing and decided about 11am that he must withdraw his forces. While his rear guards protected the evacuation, Dunsterforce loaded its personnel and equipment and by 10pm on 14 September had set sail for Enzeli.

With the withdrawal of the British, chaos broke out amongst the Azeris, the Cossacks and the refugee Armenians. Throughout the night, as the Turks drove at the remaining defences, fires, pillaging and massacres broke out in Baku. The Turks continued their artillery bombardment of the town throughout the night. By the next day, perhaps as many as 6000 Armenians were dead, many of them refugee civilians slaughtered by the Azeris. The Turks took the town on 15 September 1918. The Turks were stunned by the internecine massacre of the Armenians, but many regarded it as just punishment for the massacres of Turks in Erzurum province when the Armenians pulled out in March 1918.

Halil pushed the 15th Division northwards along the Caspian Sea to the town of Derbent, where, on 7 October the advance was halted by determined resistance. Under heavy naval gunfire from Russian fleet units, the Turks continued their attacks on 20 October. A running battle lasted for six days until the Turks shattered all remaining resistance. The 15th Division then continued to drive northwards along the Caspian coast, arriving at Petrovsk on 28 October. The division launched several attacks in early November, finally taking the city on 8 November 1918. This was the last Turkish offensive operation in World War I (occurring after the armistice) and marked the northernmost point of the Turkish advance into the Caucasus Mountains. In the south, the Ottoman Ninth Army initially had six infantry divisions assigned to its rolls when it received the mission to invade Persia and conquer Tabriz, but by the end of June 1918 two divisions had been taken away for other theatre requirements. Nevertheless, the 12th Division attacked, taking Dilman on 18 June. By 27 July, the division had beaten its way down to Rumiye. In the north, the Turks attacked and took Nachivan on 19 July 1918. Continuing down the railway towards Tabriz, the 11th Division took Tabriz on 23 August, but faced with an increasing British presence in Persia the Ninth Army’s offensive now ground to a halt.

In September, the Turks had consolidated their grip on northern Persia and held a line reaching from Astara on the Caspian Sea to Miane in Persia, about 60km (37 miles) southeast of Tabriz, and on into the Ottoman Empire near Süleymaniye. The Turks held this territory until the armistice.

Lionel Charles Dunsterville (1865–1946) was a classmate of Rudyard Kipling at the public school Westward Ho!, and became the basis for Rudyard Kipling’s character ‘Stalky’. He was commissioned into the British infantry and transferred to the Indian Army. He served on the Northwest Frontier, Waziristan and later in China. Dunsterville’s World War I service saw him initially posted to India prior to his appointment at the close of 1917 to lead a force across Persia in an effort to aid in the establishment of an independent Trans-Caucasia. He was turned back by 3000 Russian revolutionary troops at Enzeli, but was then charged with the occupation of Baku. Here he was also unsuccessful, but proved to be a resourceful and steady commander in difficult circumstances.