After the war the Allies consolidated their dead on battlefield sites and constructed formal war grave cemeteries. The Turks left their soldiers in common, unmarked graves.

In October 1918, the Ottoman leadership began to explore the possibility of exiting the war by means of an armistice with the Allies. The Ottoman Army was still in the field, fighting to defend the Anatolian heartland and seeking to secure the gains in the Caucasus. Moves soon began, though, to demobilize its forces and return the number of troops to peacetime levels.

Some historians credit Allenby’s victories in Palestine and in Syria as the proximate cause of the Ottoman decision to quit the war. This is untrue and it was the collapse of the Salonika front and the advance of General Milne’s army on Constantinople that finally convinced the Young Turks of the hopelessness of the situation. In fact, by late 1918 Constantinople was all but undefended because the Turks had sent most of their available reserves to Palestine or Caucasia. While there were troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula, these were dedicated to coastal defence. On 5 October 1918, Talaat Pasha’s cabinet decided to explore the possibility of an armistice.

Eight days later, the Ottoman chargé d’affaires in Madrid sought Spanish assistance in requesting American help to take the Ottoman Empire out of the war. Neither Spain nor America was at war with the Ottoman Empire and the Turks felt that President Woodrow Wilson’s ‘14 Points’ indicated an apparent magnanimity towards the people of the Central Powers. These efforts failed, and as Milne approached Edirne the Turks resorted to sending Major-General Charles Townshend, the defeated commander of Kut al-Amara, to the island of Lemnos to announce their intention to seek an armistice. However, by this point in the war, the unfortunate Townshend was reviled in his own country, and his mission on behalf of the enemy embarrassed both the British and the Turks. Nevertheless, this act galvanized the British and provoked the French. The Allies and the Turks then entered into negotiations, which took place in the harbour of Mudros. The preliminary discussions centred on the occupation of strategic points such as the Dardanelles and the Pozanti and Amanus tunnel complexes. Although there was dissent between the British and French, since the British had carried the weight of the war in the Middle East, the final conditions favoured them. On 30 October 1918, an armistice was signed on the deck of the battleship HMS Agamemnon.

A military parade at the Jaffa Gate. The British had approximately one million soldiers in the Middle East after the Mudros armistice. Churchill urged caution over their demobilization.

The Ottoman Army, however, was still in the field and fighting. It comprised over 25 infantry divisions as well as numerous fortresses. Moreover, the command and control structure of the army was intact and retained the ability to carry out combat operations. The Ottoman Army held large tracts of land including the Anatolian peninsula and Arabia. Significantly, it held nearly all of Russian Caucasia including the oil city of Baku. Although the Ottoman Army was clearly at the edge of collapse, with desertion a huge problem (perhaps over 300,000 men by 1918), it was still a force to be reckoned with.

The armistice found the Ottoman Army in the middle of three ongoing operations. The Yildirim Army was preparing for a determined defence of the Anatolian heartland immediately to the north of Aleppo, the Ninth Army was withdrawing forces from Caucasia for redeployment to Constantinople, and a reactivated Third Army was establishing itself in the Catalca Lines to defend the capital. These endeavours ended, and the Ottoman general staff went immediately to work to demobilize the troops and return the army to its peacetime garrisons.

Australian cavalry troops leaving Jerusalem for demobilization camp, 12 October 1918. In less than a year the British had drawn their forces in the Middle East down to less than 300,000 men. This left them unable to direct the course of events as rebellions and Turkish nationalism threatened regional stability.

In November 1918, the Ottoman Army did not simply quit the war, as Lenin remarked about the Russian Army, by ‘voting with its feet’. Unlike Germany, which had to immediately surrender 25,000 machine guns and 5000 artillery pieces, the Turks were under no such obligation. Nor did the armistice oblige them to demobilize their armies quickly. The actual schedule of demobilization was dictated by British Vice Admiral Sir John de Robeck on 26 November 1918, whereby older men would be released first in 45year-group increments; for example, the men of year groups 1897–99 began to muster out of service on 6 January 1919. The process went quickly in some areas and slowly in others, but by the end of March 1919 the Ottoman Army had only 61,223 officers and men on active duty.

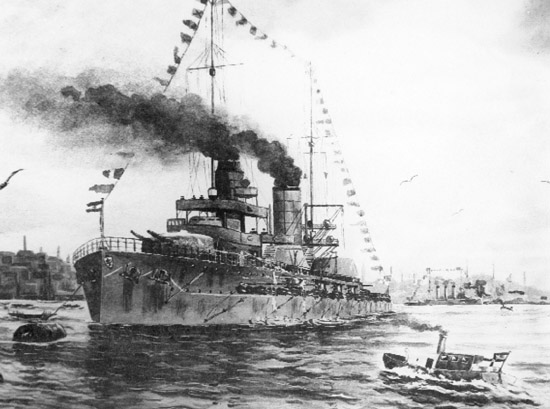

SMS Goeben of the Imperial German Navy on 1 January 1914. Memorabilia from this ship can be seen today at the Turkish Naval Museum in Istanbul, Turkey.

As planned, the re-established post-war Ottoman Army was set at 20 infantry divisions (down from a 1914 peacetime total of 36 infantry divisions). Most of the surviving infantry divisions were composed of ethnic Turks from the Anatolian heartland and these divisions were not dissolved. Although this left the Turks with divisions scattered from Edirne to Baku, the hard core of tough combat infantry divisions remained intact. Within the post-war infantry divisions, every infantry regiment maintained one battalion at 50 per cent strength and two battalions at 25 per cent strength. The divisions also maintained four artillery batteries each and 36 machine guns.

Winston Churchill characterized the SMS Goeben as the ship that brought Turkey into the war, and, in many ways, he was correct. The 23,000-ton Moltke-class battlecruiser was launched in Hamburg in 1911. She carried ten 11in guns and twelve 5.9in guns and could steam at 28 knots carrying over a thousand sailors. The Goeben was transferred to the Ottoman Navy on 16 August 1914 and renamed the Yavuz Sultan Selim. The ship participated in the Black Sea raids that brought Turkey into the war and fought several engagements against the Russian fleet over the next two years. The Yavuz emerged from the Dardanelles on 10 January 1918 to sink two British monitors, but was badly damaged by mines returning from her sortie. She survived the war to become the flagship of the new Republican navy. The ship was modernized in 1936 and finally decommissioned in 1954. The Yavuz was the sole surviving battlecruiser from World War I and was offered for sale in the 1960s. Unable to sell the ship the Turkish Government sent her to the scrap yard in 1973 where she was broken up by 1976. She outlived almost all of the men whose fate she had altered in 1914.

By 27 January 1919, the Turks were simultaneously demobilizing and implementing the new force structure, much to the dismay of the British commanders trying to occupy the key strategic points of the empire. These smaller divisions gave the Turks a force of about 40,000 infantrymen under arms with 240 cannon. There were additional men assigned to the Gendarmerie and to the supply services. Altogether 48,000 men carried rifles. However, there were 791,000 rifles, 4000 machine guns and 945 artillery pieces stored in depots deep in the Anatolian heartland, which allowed them to mobilize the 20 cadre divisions at full strength as well as arm 10 additional divisions if needed. The garrison cities of the post-war army were spread more or less evenly throughout what is now modern Turkey. Also differing from the treaty restrictions covering the Germans, the Turks were not forced to disband their general staff nor to disenfranchize the tough core of emerging leaders seasoned in the cauldron of war.

A British funeral procession in the Middle East, with the soldiers bearing reversed arms. This common military practice is thought to have first occurred at the Duke of Marlborough’s funeral in 1722.

The human cost of World War I in the Middle East remains hard to calculate, and there are a variety of contradictory figures. This is true concerning the number of civilian casualties as well, especially among the Ottoman Armenians. A total of 325,000 Ottoman military dead (from wounds and disease) is the number most commonly cited. This total seems to have originated in Commandant Larcher’s 1926 book, but is considerably lower than the totals listed in the modern Turkish official histories. In fact, the Ottoman Army lost around 426,000 military dead or about 17 per cent of the 2.6 million men mobilized. Of course, these figures only present military losses, to which must be added the huge loss of life and productivity of the Muslim, Armenian and other Ottoman civilians killed or injured during the war.

In geographic terms, the Turks began the war with 2,410,000 square kilometres (930,500 square miles) of territory inhabited by 22 million people; after Mudros they retained 1,283,000 square kilometres (495,370 square miles) of territory inhabited by 10 million people (most of whom were Turks). Substantial parts of the most productive area of the empire were occupied by foreign powers. The economy was ruined, coal production had fallen to almost nothing, and the empire’s former enemies and neighbours began to take even more territory from her.

Allied casualties are equally hard to assess. Britain sent about 1.5 million Britons, Indians, Australians and New Zealanders against the Turks and suffered 264,000 casualties. Russian casualties surely equalled this, while the French suffered probably fewer than 50,000. Moreover, the British Army was forced to keep a number of infantry divisions in the Middle East, which proved costly in both financial and political terms and led to a crisis in government in 1922. Field Marshal Lord Carver, writing in 1999, thought that the war against the Turks was a terrible waste of effort and diverted scarce resources from the French theatre.

The proposed divisions according to the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916. This secret agreement between Great Britain and France, with Russia’s assent, broadly divided up Ottoman territory, allowing the controlling powers to decide on state boundaries within these areas. With a few casual strokes of a pencil on the map of the Middle East, Mark Sykes and François Picot altered forever the geopolitical balance of the region. The unanticipated consequences of their work still linger today.

The treaties that formally ended World War I established what has been called ‘a peace to end all peace’. This is an accurate assessment that reflects the many problems that afflict the modern world as a consequence of the destruction of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Empire lay at the heart of the ‘Eastern Question’, which centred on the balance of European power in the Near East. However, the outcome of the war as framed by the various treaties was incompletely developed and led to a series of events that defined the world of the late twentieth century. The ‘Eastern Question’ is still with us, and one has only to look to Bosnia, Kosovo and the Balkans; Georgia, Armenia and the Caucasus; Iraq, the Kurds and the Tigris-Euphrates basin; Israel, Lebanon and Palestine; and the resurgent Islamic fundamentalism coming out of the Arabian peninsula, to understand the degree of instability wrought in 1919.

To a large degree, the problems began in 1915 when a series of letters were exchanged between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Cairo, and Hussein ibn Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, promising independence in return for revolt against the Ottomans. The activities of the Arab Bureau in Cairo and those of T.E. Lawrence further inflamed Arab nationalism. However, in May 1917 Sir Mark Sykes of Britain and François Georges Picot of France arrived at a diplomatic agreement, which today is regarded as watershed benchmark in the history of the modern Middle East. The agreement, termed the Sykes–Picot Agreement, envisioned a post-war settlement that divided the Ottoman provinces between the two nations. In general, France claimed Syria and Lebanon, while the British (who were engaged on the Turkish fronts to a much greater degree) took just about everything else (including Mesopotamia, Arabia and Palestine). The Sykes–Picot Agreement became the basis for the division of spoils at Paris in 1919. Compounding this in November 1917 was the ill conceived British Balfour Declaration that pledged a future Zionist homeland for Europe’s Jews while simultaneously promising not to displace or penalize the Arabs. There were also French promises made to the émigré Armenians to reconstruct an Armenian state in the eastern Ottoman provinces. Added to these layers of proclamations, Colonel T.E. Lawrence became a self-proclaimed advocate of Arab nationalism and further inflamed the Arab leaders by suggesting to them that independence would be bestowed upon them at Versailles. Lawrence even accompanied the Arab leaders to Paris dressed in the flowing robes and burnoose of a desert sheik, much to the discomfort of the British delegation.

The peace in the Middle East was a multi-stage process. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919, while not affecting the Ottoman Empire directly, established the League of Nations mandate system, which was aimed at the administration of the ex-German colonies. It was extended to include the Ottoman territories occupied by the Allied armies. Later, at the Conference of San Remo in April 1920, the British and French agreed to honour the Sykes–Picot Agreement and divide the Ottoman Empire along the lines discussed in 1917. The Treaty of Sèvres, signed on 10 August 1920, formally ended the Ottoman war and was as harsh and punitive as its predecessor signed at Versailles. In the treaty, the Ottoman Empire lost almost all of its non-Turkic provinces, including Arabia, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Syria, which then became mandates of the British and French. However, the treaty went much further and dismembered Anatolia by creating the independent states of Armenia and Kurdistan. The important city of Smyrna and most of the Aegean islands were promised to Greece. The rump Ottoman Government was forced to sign the treaty in the face of great public opposition from the Turkish people.

In many ways, the Treaty of Sèvres was a causal agent in the rise of Turkish nationalism in 1921–22. Mustafa Kemal and others were so incensed by the harsh terms of the treaty that they formed a nationalist government and raised a nationalist army. Kemal and his army went on to expel the invading Greeks from western Anatolia and forced the Italians and French from the south and southeast, as well as making it impossible for Britain to remain in control of Constantinople and the Dardanelles Straits. By late 1922, Kemal had carved out the borders of modern Turkey. The unhappy Allies returned to the conference table and hammered out the Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923. The new treaty annulled the Treaty of Sèvres and established most of the current borders of the modern Republic of Turkey.

The signing of the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 1920. The treaty would later be annulled following the Turkish War of Independence (1919–23).