Supporters of the Young Turks in Jerusalem, 1909. Much of the early leadership of the Young Turk movement evolved in provincial cities like Salonika and Damascus, where its members could gather in secret and in safety. By 1909 these had become hotbeds of revolutionary activity.

Many conventional ideas about the Ottoman forces engaged in World War I in the Mediterranean and Middle East are unbalanced, such as their army being inherently corrupt, inefficient and prone to collapse. Western historiography tends to present a dismal picture of the Ottoman Army at war. This volume hopes to provide a more balanced look.

The historiography in English of World War I in the Middle East that has evolved over the past 90 years is wide ranging, but tends to be focused on particular campaigns, leaders or units. There are few books that put together a single unitary picture of the entire Middle Eastern theatre, and those that do tend to focus on military, political or cultural matters. Moreover, even today the history of this theatre remains deeply rooted in English and German sources. This situation, of course, was directly caused by the lack of availability of Ottoman or Turkish sources. In fact, in the most widely regarded definitive work on the Turkish fronts, written by the French commandant Maurice Larcher in 1926, only a quarter of the cited sources were Ottoman. The resultant historiography, in turn, tends to tell the story from an overwhelmingly European perspective, which in many ways reflected what the Europeans saw or perceived, rather than reflecting what actually occurred. Today, this situation is rapidly changing, as historians take a fresh look at the events of 1914–18 through the lens of the Ottoman archives and Turkish narratives.

As a result of the way the history of World War I in the Middle East has evolved, there are many popular ideas about the war in this theatre that are largely untrue. For example, one is that the Turks often had large numerical superiorities of men (in most cases they were outnumbered). Another is that German generals provided most of the competent leadership and professional staff work for the Turks. There is also the idea that the Ottoman Army was incapable of modern military operations due to corruption and inefficiency. Finally, many histories present the idea that the Turks suffered unusually high numbers of casualties in campaigns against the Allies. For example, in the Gallipoli campaign, a commonly cited figure by British authors suggests that half a million Turks became casualties, whereas the actual number of Ottoman casualties was about 220,000. Finally, there is a pervasive myth that Arab soldiers serving in the Ottoman Army were unreliable and prone to collapse. None of these ideas are true, and in general Western historiography presents a dismal picture of the Ottoman Army at war, in which Turkish successes are largely attributed to Allied mistakes, the activities of German generals or inhospitable terrain and conditions. With these ideas in mind, this volume hopes to provide a balanced look at the Turkish fronts in the Middle East during World War I.

Although many of those in the Young Turk movement were military officers, some were civilians and government officials. All shared a desire to westernize and modernize both the Ottoman state and society

The Ottoman Empire reached its zenith of power in the seventeenth century, after which it suffered a gradual decline characterized by a loss of competitiveness with the emerging European nation states. In the eighteenth century, the Ottomans lost territory in Hungary and the Balkans to Austria. Similarly, the Russians under Peter and Catherine took back the Black Sea coasts and the Crimea. The Mamluks took control in Egypt, and along the North African coast gained autonomy. The early nineteenth century saw the independence of Greece and Serbia, while Russia seized most of the Caucasus. The Ottoman sultan attempted a programme of reform, called the Tanzimat, which attempted to strengthen the government and the military. European advisers were hired, and attempts were made to create model structures. The Crimean War (1853–56) overtook these efforts and the Turks were set farther behind.

By the 1870s the English press had dubbed the Ottoman state ‘the sick man of Europe’, and it seemed destined to fragment piece by piece as the European powers took its land and its own ethnic minorities gained independence. From this notion grew the ‘Eastern Question’, which attempted to frame what the future Middle East might look like politically when the Ottoman Empire finally collapsed. Three of the Great Powers concerned themselves with the Eastern Question: Great Britain, France and Russia. The British interests lay in the security of the Suez Canal and the security of India. The French were interested in spreading influence in the Levant and eastern Mediterranean. The Russians wanted access to the Mediterranean through control of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, as well as acquiring territory in the Caucasus and Trans-Caspian region. In a nutshell, Britain supported the continuation of the Ottoman state while the Russians wanted to destroy it.

The 1870s brought significant growth to the nationalist ambitions of many of the ethnic minorities within the Ottoman Empire, particularly the Bulgarians, Albanians, Macedonians and the Armenians. Firebrands within these communities formed revolutionary groups dedicated to independence by force of arms. In Bulgaria in 1876, a nationalist insurgency resulted in a violent Ottoman campaign of repression and massacres. These ‘Bulgarian horrors’ as they were termed led to the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. In truth, Russia and many Europeans supported and encouraged the Bulgarians to rise against the Turks. In any case, the Tsar unleashed his armies on the Ottoman provinces in the Balkans and in the Caucasus. The Russians quickly pinned the Turks in several fortresses and drove them back to the outskirts of Constantinople while taking Batum and Kars in the east. They forced the Turks to sign the Treaty of Santo Stefano, which created a Greater Bulgaria under the wing of the Russians. The new Greater Bulgarian state had access to the Mediterranean Sea and was regarded as a puppet of the Russians.

A scene from the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. Although ultimately defeated in the war, the Ottoman Army successfully defended the city of Plevna against greatly superior Russian forces using field entrenchments. The siege of Plevna foretold the kind of fighting that would characterize much of World War I.

Enver Pasha was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1899 and went shortly thereafter to the Ottoman War Academy, graduating in 1903. He served in Salonika and then in 1909 as an attaché in Berlin. In the Balkan Wars he participated in the amphibious invasion of Sarkoy as X Corps chief of staff and was hailed as the liberator of Edirne (Adrianople) in 1913. Enver was appointed as Minister of War in January 1914. He was aggressively nationalistic and was prone to making reckless decisions with incomplete information. After the war he fled to Russia and was killed leading a cavalry charge in the Caspian region.

Enver Pasha (pictured at centre with the moustache) was charismatic, reckless and flamboyant. He would die as he lived, in a forlorn hope.

The treaty so destabilized the balance of power in Europe that Bismarck convened the Congress of Berlin in 1878. Supported by the British and the Austrians, Bismarck managed to dismantle the Santo Stefano Treaty and restore to the Turks much of what they had lost. In the end Bulgaria survived, but with a much reduced area. The Treaty of Berlin in 1878 was a reprieve for the Turks that allowed them to resume modernization and Westernization. It should be noted here that the Europeans, including the British and French, maintained an iron grip on the Ottoman economy by the imposition of capitulations dating back to the late 1700s. These capitulations granted the Europeans favourable trade privileges that were largely tax free and were a festering wound in European–Ottoman relations.

As the twentieth century approached, many young Turkish army officers and civil servants grew disenchanted with the pace of modernization and formed a secret group called the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). They were popularly known in the West as the Young Turks. The CUP was dedicated to the overthrow of the sultanate and the establishment of a Western-style parliamentary democracy. The first among equals of the CUP was the Salonika Group, centred on officers of the Ottoman Third Army. On 23 July 1908, the Young Turks forced the sultan to abdicate peacefully. However, a counter- revolution in April 1909 pushed the Young Turks briefly out of power, until the Action Army marched on Constantinople to depose the sultan on 27 April 1909. Many of the future leaders of the Ottoman Government and the later Turkish republic were prominent members of the CUP at this time, including Enver, Taalat, Cemal and Mustafa Kemal.

The new government was, at first, democratically inclined and open to the idea of minority participation. However, over the next several years CUP ideology hardened and the rights of the minority communities were decreased. Naturally, this generated much unhappiness and led to the revival of the revolutionary committees. In turn, fresh insurgencies and violence broke out in Albania, Macedonia, Yemen and parts of the eastern provinces inhabited by Armenians and Kurds. In 1911, Italy invaded Libya, the last Ottoman province in North Africa. The war ended in 1912 with the loss of Libya and the Dodecanese islands. While this scarcely damaged the empire, it affected the prestige of the government.

Sensing weakness, the Balkan Christian states formed an alliance in the autumn of 1912 and attacked the rump Ottoman provinces in the Balkans. Epirus and Thessaly, including Salonika, quickly fell tothe Greeks. The Serbs took the province of Novi Bazar and split Macedonia between themselves and the Bulgarians. The Bulgarian main army besieged Edirne (Adrianople) and marched to the Catalca Lines (just to the west of Santo Stefano), which was a suburb of Constantinople. A brief armistice was called in December 1912, and negotiations started in London. At the London Conference the Ottoman Government was forced to concede a position that gave away the Balkan provinces in their entirety, as well as Edirne and the Aegean islands.

When the terms of the pending agreement were made known, the government appeared as weak, hesitant and unpatriotic. There was much resistance from the army and from the hard-core ideologues within the CUP, and these men determined to act. On 23 January 1913, an aggressive triumvirate composed of the CUP members Enver, Cemal and Taalat seized power in the famous Raid on the Sublime Porte. In what amounted to a coup d’état, they murdered the Minister of War and forced the Grand Vizier, Kamil Pasha, to resign at gunpoint. They quickly installed one of their own, Mahmut Sevket Pasha, as the new Grand Vizier and vowed to continue the war. The armistice then broke down in February 1913. The new government, however, was unable to conduct the war any better than its predecessor, and the Ottomans continued to lose ground and personnel. The First Balkan War finally came to an end with the Treaty of London in June 1913. A Second Balkan War broke out shortly thereafter between the former Christian allies, during which Romania, Montenegro, Serbia and Greece attacked Bulgaria. The Turks stood aside, except for the peaceful reoccupation of Edirne.

The 1878 Congress of Berlin. The German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, disturbed by the Russian creation of a Greater Bulgaria after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, orchestrated a cancellation of the Tsar’s war gains. In doing so, Bismarck prolonged the life of the Ottoman Empire into the twentieth century.

Cemal Pasha was an army officer who rose because of his connections with the CUP (Young Turks). He served in the Balkan Wars and in January 1913 was appointed as Minister of the Marine (the navy). At the outbreak of the war, Cemal took command of the Fourth Army in Syria and presided over operations in Palestine. Because of his lacklustre performance, he was marginalized in 1918 and replaced as a front-line combat commander. Because of his role in the Armenian deportations and massacres, Armenians tracked him down and killed him in Tiflis in 1922.

Cemal Pasha photographed at the Dead Sea, 3 May 1915. Political intrigue was his strong suit, and he was prone to leaving military decisions to others.

Ottoman casualties in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 totalled about a quarter of a million men. Moreover, it lost its most productive and wealthy provinces, and millions of Muslim inhabitants from those provinces streamed into the empire. This created great hardship as the government struggled to absorb the influx of refugees. Militarily, the Ottoman Army lost an entire field army of 12 divisions, including its equipment, artillery and munitions. Politically, the Balkan Wars brought to power the triumvirate composed of Enver, Cemal and Taalat and it solidified their grip on the government. To the Ottoman public these men appeared as heroes who had overturned the Treaty of London and restored the historic city of Edirne to the empire. In the main, they (and their associates) were Western in their orientation, secular and were graduates of the Ottoman Military Academy or universities. All three were ambitious and had a common agenda of rebuilding Ottoman society on a Western model based on a constructed Turkish national identity. Importantly, their success gave them confidence and seemed to confirm a sense that their own destinies were conflated with that of the nation. In particular, Enver Pasha, the new Minister of War, became imbued with a reckless sense of self-assurance, which would prove deadly to the people of the Middle East in the coming years.

Turkish cannon destroyed by Bulgarian forces, in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13. The defeat and rout of the Ottoman Eastern Army by the Bulgarians in 1912 appeared to demonstrate that the Turks were inept and careless soldiers. This misappraisal caused the Allies to severely underestimate the potential of the Ottoman Army in 1914.

The Italian cruiser Morosini discharging her 305mm guns on 24 April 1912 at the Dardanelles, during the Italian–Turkish War of 1911–12. The Italian fleet was unable to blockade the Dardanelles effectively, but was instrumental in the seizure of Rhodes and the Dodecanese from the Turks.

Asia Minor and the Middle East in 1914. Although greatly reduced in size after the Russo-Turkish and Balkan wars, the Ottoman Empire still extended over 2.4 million square kilometres and was inhabited by an estimated 22 million people.

By 1914, the Ottoman Empire was beset by hostile foreign interests and internal decay caused by nationalism and resistance to modernity. During the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, it lost almost all of its European provinces and the ‘sick man of Europe’ seemed about to expire. The Ottoman Empire was a geographically widespread, multi-national and multi-ethnic empire, whose predominately Muslim population was composed mostly of uneducated peasants in rural communities. About 22 million people lived in the empire, of which about 11 million were ethnic Turks, the remainder being Arab, Armenian, Greek, Kurd or one of dozens of tribal entities that peppered its territory. Many of the ethnic minorities had interests overtly hostile to the continued existence of the empire. Although the correct term for the empire and its people was ‘Ottoman’, the Europeans continued to refer to them collectively as the Turks (these terms will be used interchangeably in this book). Industrialization was almost non-existent, and the empire’s chief products were agricultural. The empire produced no steel, and its coal production was less than Italy’s or about 1/300th of Great Britain’s. Communications within the empire were poor and commerce was dominated by foreigners, who operated under favourable trade concessions known as the capitulations. In particular, the railroad network was built piecemeal by foreigners to accommodate their own commercial interests, rather than to accommodate the military interests of the empire.

‘The Turkish Army is not a serious modern army…It is ill commanded, ill officered and in rags’

Colonel Henry Wilson, Director of Military Operations, October 1913

In contrast, the soon-to-be enemies of the empire were heavily industrialized Britain, France and Russia. Britain and France were world-class colonial powers that could call on the human and natural resources of vast empires – 45 million people lived in the British Isles alone. The Russians were industrialized to a lesser extent, but enjoyed an almost limitless population. There was historical enmity between the Ottomans and Russians and they had fought three major wars in the nineteenth century. Even in 1914, the Tsars still coveted the Bosporus and the Dardanelles. On the other hand, Britain and France maintained historically friendly ties with the Ottoman Empire, mainly to counterbalance the growing power of Russia. Because of this, when war broke out, the Turks were both intellectually and physically unready to wage war against Britain or France.

The Ottoman Army was torn apart by its defeat at the hands of the Balkan League. This seemed to validate European notions that the army was inefficient, corrupt and incapable of effective combat operations. However, the Young Turks recognized the need for reform and began a sweeping series of changes that restored much of, and actually improved, the Ottoman Army’s capabilities.

The army had 36 combat infantry divisions in 1914, which were manned partially at a cadre level, giving a peacetime strength of about 200,000 men and 8000 officers. There were no organized cavalry divisions, but the Turks were able to mobilize their mountain tribesmen into an irregular cavalry corps on the outbreak of war. The active army was composed largely of illiterate peasants, who were called to the colours for a period of three years. There was also a reserve system, but in 1913, as a result of the dismal performance of reserve units in the Balkan Wars, the general staff entirely eliminated its organized reserve combat divisions and corps. They replaced them with a depot regiment structure designed to bring the units of the active army up to strength. Thus, when the army entered the war – and in contrast to the European powers, who mobilized scores of reserve divisions and corps – the Ottoman Army did not immediately increase the number of its combat divisions. To make matters worse, weapons and equipment – especially machine guns, cannons, munitions, medical supplies and communications gear – were in short supply.

The army was blessed, however, with three important advantages that would enable it to endure through a multi-front war for four years. The first was the existence of a body of general staff officers whose selection and training were based on the extraordinarily successful Prussian model. These officers were young, but were combat seasoned and professional. The second advantage was a unique, combat-tested, triangular infantry division instituted in 1910. Each division contained three infantry regiments of three battalions each, a model that was ideally suited to trench warfare and which would soon be adopted by the European powers. This organizational structure was flexible, and enabled the Ottoman Empire to build an expansible army of some 60 effective divisions as the war progressed. Finally, the Ottomans had a remarkably resilient soldier in its average asker, who although illiterate was tough, well trained and generally brave (the Turks called their soldiers Mehmetcik or Mehmets). In truth, the strength of the Ottoman Army lay at the extreme ends of its structure – a solid base of soldiery and a proficient high command.

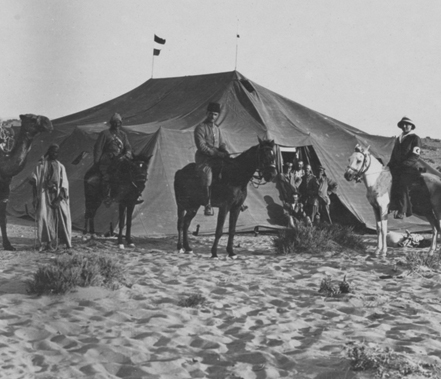

Reki Bey, military commander of Jerusalem, and his staff during manoeuvres south of Jerusalem before the Turkish declaration of war. The Ottoman Army conscripted men locally into regimental depots for training. Consequently, the soldiers in Ottoman Army units in the Damascus and Jerusalem areas were mostly Arabs, who neither spoke nor read Ottoman Turkish.

In the year prior to the outbreak of World War I, the army undertook a massive retraining and reconstitution effort to rebuild its shattered forces. Its garrisons were located in the major cities, and it was organized for peacetime in a system of army inspectorates. The Minister of War, Enver Pasha, wrote and implemented dynamic training guidelines, whichwere based on lessons learned from the recent wars. These guidelines stressed mobility, combined-arms operations and the importance of fire superiority. They also included instructions for digging trenches and immediate counterattacks. These tactical hallmarks would characterize the Ottoman Army in World War I and would make it a deadly opponent when fighting on anything near equal terms.

In December 1913, following a request from the sultan, the German general Otto Liman von Sanders arrived to head the German Military Mission. The latter initially comprised 40 highly trained officers tasked with helping the Turks rebuild their army. The German officers would assist mainly as high-level staff officers, but some would actually command Ottoman combat units. None of them spoke Ottoman Turkish, nor were they familiar with the new organizational structure; all of them held the Turks in very low professional regard. These officers began arriving in the spring of 1914, although many did not actually arrive at their duty stations until the summer. Such help was not new: Germans had helped the Ottoman Army since before the Crimean War, and these men followed in the footsteps of illustrious officers including Graf von Moltke and Colmar von der Goltz.

The German Maxim Maschinengewehr ‘08. The Ottoman Army mostly used German machine guns during World War I. In 1914, such weapons were in short supply. Resupply from Germany post 1916 helped alleviate this situation.

The Allies’ contemptuous opinion of the Ottoman Army was reinforced by the reports from the British Army attaché Lieutenant-Colonel Cunliffe-Owen, resident in Constantinople between 1913 and 1914. He viewed the Ottoman attempt to rebuild the army as feeble and clumsy. Other British opinions appeared to confirm this: the director of military operations characterized the Ottoman Army as ‘ill-commanded, ill-officered and in rags’. As late as autumn 1914, reports from the field to London contained phrases like ‘very much afraid of the enemy’s bayonet’ and ‘inferior physique, nervous and excitable’. The French and the Russians formed similar opinions.

The British Army was small and based on an unusual model of professional long-service volunteersoldiers. It also possessed the finest non- commissioned officer (NCO) corps in the world, although it still drew the bulk of its officers from the privileged classes. There was a regular army of six infantry divisions, but a further half a dozen could be mustered by bringing together the various battalions on foreign stations. This was backed by a reserve force called the Territorials, which could mobilize another 14 divisions for war. At the level of the individual soldier, the British had no equal in the world; however, their army was tightly compartmentalized, and the individuality of the different arms – infantry, cavalry and artillery – contributed to an overall inability to combine arms in combat. Another significant weakness in the army was the relative newness of the general staff and a general absence of modern doctrines of command and control. In 1914, instead of distributing the regulars among the reserves and the new ‘Kitchener armies’, the British concentrated their professionals in the British Expeditionary Force in France, where large numbers were slaughtered. This, of course, hurt the newly raised armies, which numbered 62 divisions by 1917, by leaving them largely without trained leaders.

The Russians, at the other end of the spectrum, used a mass continental army model that employed huge numbers of conscripted men. The army was famous for its inefficiency and for its lack of a professional NCO corps. It also lacked equipment, but was undergoing a modernization of its artillery force in 1914. At higher levels the Russians had a professional general staff whose officers were seasoned veterans of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). Like the Ottoman Army, the soldiers of the Russian Army were mostly illiterate peasants from agricultural villages scattered throughout the empire. Moreover, the Russian Empire was also a multi-ethnic one, and many of the conscripts spoke no Russian and had national interests overtly hostile to the Tsar’s government. Nevertheless, the army was famous for its numerical strength and its ability to endure and persevere in difficult conditions.

The British Maxim .45 Mk 1. Like its Ottoman opponent, the British Army in the Middle East was underequipped with machine guns. Indian Army units in particular suffered from chronic shortages until late 1918.

The French Army was a highly professional force composed of active and reserve divisions and corps that trained together on a regular basis. Every healthy Frenchman served in the military for three years, and then remained in the reserves thereafter. The French staff was well trained and the army well equipped. In large numbers, the French would only fight the Turks at Gallipoli, although a small number participated in the Palestine campaign late in the war.

The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo provoked the July Crisis of 1914 during which Austria-Hungary and Serbia spiralled into war. Diplomacy failed and ultimatums were followed by military mobilization of the partners of the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente. The war-weary Turks watched these unfolding events at a distance, but because they were not in either alliance they maintained their neutral posture. The alliance partners, for their part, attempted to woo or bully the Turks into a commitment to support them in the event of war. In addition to the German Military Mission, there was a British Naval Mission, and a French Mission that was training the substantial forces of the Ottoman Gendarmerie. The Russians, for their part, spied on the Ottomans and supported the activities of the Armenian Revolutionary Committee, which sought autonomy or independence. These competing concerns, as well as the diplomatic activities of the embassies in Constantinople, pressured the Ottoman Government, which in turn led to the emergence of interests and factions among the Young Turks.

Although individual German officers had served in the Ottoman Empire it was not until 1882 that a formal German Military Mission was established under General von Kaehler. He died the following year, but the work was continued by Lieutenant- Colonel Colmar von der Goltz, a trained general staff officer who was already well-known as the author of The Nation in Arms (Das Volk in Waffen). Goltz would remain in the empire until 1896 and established the German staff curriculum in the Ottoman War Academy. This curriculum included doctrines and concepts about mass continental armies, conscription and mobilization, and battles of encirclement and annihilation. He returned in 1909 to assist the Turks in reorganizing their army into a modern army corps configuration. When Liman von Sanders arrived in 1913 to re-establish the moribund mission, German ideas were already well in place in the Ottoman Army. Goltz himself returned to command the Ottoman Army in Mesopotamia, where he died in 1916.

A German station at Abou Augeileh.

It is clear today that all of the European powers had defined war objectives, which served to strengthen the will to wage war. The French, for example, wanted to recover Alsace-Lorraine, while the Austro-Hungarians wanted to stop the rising Serbian hegemony in the Balkans. In contrast, the Ottoman Empire, in the wake of its Balkan defeat, had no definable war goals in the summer of 1914, neither did it have any sort of offensive mobilization scheme or war plan. Indeed, the priority of its military was the rebuilding of the army and it was unprepared for war. In truth, the Turks had almost nothing to gain from entering a general European war, and the ruling Young Turks made overtures to both alliances as the Balkan crisis progressed. However, powerful personalities, in the form of the German ambassador Hans von Wangenheim and the pro-German Ottoman Minister of War Enver Pasha, seized the moment and propelled the empire towards provocative action.

Wangenheim and Enver conducted detailed conversations on 27 July, leading to the drawing up of the famous Secret Treaty of Alliance between Germany and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty was not a formal alliance, but the parties pledged to support each other and, importantly, from the Ottoman perspective the agreement was defensive in nature. Only in the event of active military intervention by the Russians were the Turks obliged to enter the war. As these discussions evolved, World WarI broke out on 1 August 1914 and the next day the ambassador and the Minister of War signed the treaty. The clauses of the treaty were technically overcome by events, and made irrelevant by the German declaration of war without waiting for Russian intervention. The treaty itself did not bring the Turks into the war, but aligned them with the Germans and alienated them from the British and French.

The Young Turks were not a cohesive governing body and the Grand Vizier, Prince Sait Halim, who was also Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, was surprised to learn of the signing of the treaty. It is certain that he did not want war; indeed, some of the Young Turks were even pro-Allied, the Ottoman Empire having long-standing friendly ties with Britain and France. But within days the insistent demands of the aggressive German ambassador began to worry Sait Halim, who in turn now pressed the Germans for additional concessions, which included a promise to help end the capitulations, certain territorial clauses involving Ottoman irredentist claims in Caucasia and the Aegean islands, and a war indemnity. Wangenheim, who was seeking a safe haven for the German Navy’s Mediterranean Squadron, agreed to these proposals.

Troops of the Young Turks man an artillery piece in Pera, 1909. The Ottoman artillery was composed largely of German-manufactured weapons in the calibre range of 77mm to 105mm. Most of these weapons were flat trajectory guns. Howitzers (with high-angle trajectories) were comparatively few in number.

Over the next several days, a deeply disturbed and wavering Sait Halim met with his cabinet to thrash out exactly where Ottoman foreign policy was heading. On 9 August 1914, he directed that the Secret Treaty be examined for its legality, because he did not believe that it obliged the empire to enter the war. He also sought to conclude alliances with Bulgaria and Romania and to convince the Entente powers that the Ottoman Empire intended to remain neutral. It is evident today that Sait Halim did not want war and intended to buy as much time for his country as he could. Unfortunately for the Ottoman Empire, and perhaps the world as well, Sait Halim proved to be a reluctant and hesitant leader, who was incapable of controlling the actions of his government.

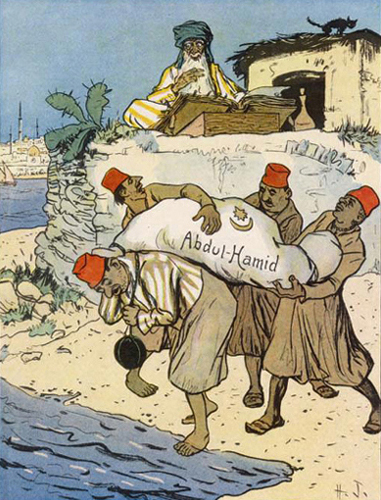

A cartoon commemorating Abdülhamid II’s deposition on April 27, 1909. The Young Turk revolution swept away the archaic Hamidian regime, but it in turn was overthrown by a counter-revolution. However, in 1913 the Young Turks seized power once again in the ‘Raid on the Sublime Porte’.

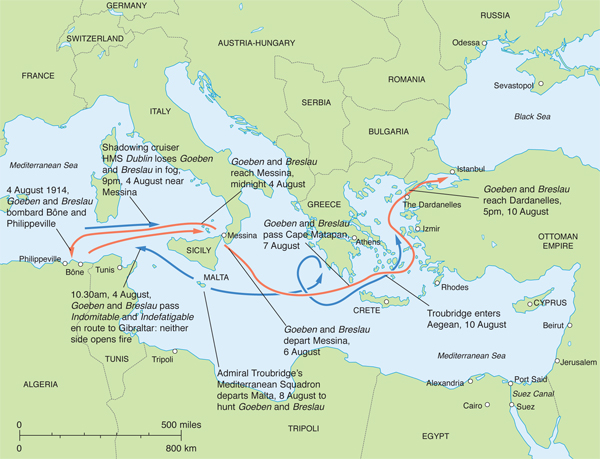

The events of the summer of 1914 conspired to overcome the concerns of the Ottoman Government, and served to bring the Turks into the war. One of the most famous episodes of the war was the flight of the Goeben, a heavily armed German battlecruiser that was the flagship of Rear Admiral Wilhelm Souchon’s Mediterranean Squadron, and the light cruiser Breslau. The outbreak of war found the German squadron trapped inside the Mediterranean Sea and hunted by superior British naval forces. Souchon, who was ordered to interfere with French forces coming from North Africa, eluded his pursuers, and instead of sailing for the friendly ports of Germany’s ally Austria- Hungary, sailed for the eastern Mediterranean. Ambassador Wangenheim, alerted to the situation, persuaded the Young Turks to allow Souchon’s squadron to enter the Dardanelles and find safety. On 10 August, the ships passed through the straits and anchored off Constantinople the following day. The resourceful admiral’s escape deeply embarrassed the Royal Navy. Britain was in turn partially to blame for the Turkish decision to harbour Souchon, when she seized two Turkish battleships (paid for by public subscription) under construction in British yards on the outbreak of war.

The flight of the Goeben and Breslau across the Mediterranean in August 1914. This was one of the key episodes that drew the Ottomans into World War I on the side of the Central Powers.

HMS Erin was a Royal Navy battleship of the King George V class originally built for Turkish Navy as the Reshadiye. However, following the declaration of war against the Ottoman Empire, she was ordered to be seized by the British Government, and was retained for Royal Navy service.

The arrival of the German squadron destabilized the delicate political balance in the Ottoman capital. To avoid internment, and capitalizing on a wave of Anglophobic hysteria caused by the seizure of the Turkish ships, the Turks ‘purchased’ the German ships and reflagged them, with the German sailors famously appearing on the decks wearing the Turkish fez. Souchon was appointed as an admiral in the Ottoman Navy and was given command of the Ottoman fleet, thus maintaining control of the Kaiser’s ships. The charade fooled nobody, and instead drove the British to begin planning for war against the Turks. Meanwhile, Otto Liman von Sanders, whom some of the Young Turks mistrusted, was sidelined as a player in the diplomatic processes by being put in command of the Ottoman First Army. Unlike Liman von Sanders, Souchon remained in command of an instrument of war that Germany could wield independently.

Throughout the autumn of 1914, Enver wrestled with the reluctant Sait Halim over the prospect of entering the war. Left to their own devices the Young Turks might not have entered the war, but the collaboration of the determined Souchon and the aggressive Wangenheim sealed their fate. Although Sait Halim was nominally the commander of all Ottoman forces, in reality Enver controlled them, and, working with the Germans, the latter was manoeuvring the empire into war. In September 1914, Souchon began taking the Goeben (now renamed the Yavuz) and her consorts out into the Black Sea, on what were termed ‘training cruises’. In reality, he was hoping for a chance to confront the Russian Black Sea Fleet, as such an action would be considered a casus belli and would bring the Turks into the war. Sait Halim saw through this, and prohibited Souchon from exercising in the Black Sea, although Souchon continued sailing. The Russians, however, refused to take the bait.

Enver now took matters into his own hands, as well as several million Turkish pounds of gold from the Germans, and orchestrated the entry of his country into the war by encouraging Souchon to continue his sorties. In violation of Sait Halim’s directives, Souchon took his ships and most of the Ottoman fleet to sea on 28 October 1914. It is possible that neither Enver nor his clique of interventionists knew Souchon’s true intentions, thinking only that a high-seas engagement with the Russians would result. Early the next morning, however, four task forces of Ottoman ships began to bombard Russian Black Sea ports, including Sevastopol, Odessa and Yalta. Unlike the Japanese surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur in 1904, these widely dispersed attacks were not designed to cripple Russian sea power, rather they were designed merely to provoke the Russians, making them a political and not a military act. Sait Halim and the advocates of restraint had been outmanoeuvred by Enver and the Germans, who had stage-managed the whole provocative incident. On 2 November 1914, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, swiftly followed by Britain and France.

Both Winston Churchill, the British First Lord of the Admiralty, and Henry Morgenthau, the American ambassador in Constantinople, thought that the passage of Souchon’s squadron through the Dardanelles made the Ottoman entry into the war inevitable. This is largely true, but it was more a combination of the strong personalities of Enver, Wangenheim and Souchon that brought this about. Unfortunately for the Ottomans, even at this late date, their empire was quite unready for a major conflict against the Allies.

SMS Goeben was a Moltke-class battlecruiser armed with 11in guns. She was fast, well armed and heavily armoured. At the outbreak of war, she was more than a match for any combination of Allied ships that might engage her.

Although not at war, the Turks mobilized their army on 2 August 1914, mainly as a precaution against their Russian and Christian Balkan neighbours. Unlike the Great Powers, they had no immediate offensive plans and their single war plan, which was rewritten in April 1914, brought the bulk of the army to Thrace against Bulgaria and Greece. The process of mobilization, which comprises bringing an active army and its reserves to a readiness posture enabling it to fight wars, had been perfected by the European armies, with timetable precision, so that it took about 10 days (for the Russians it took longer).Following this, armies concentrated on the frontiers by railway and then executed their war plan. The most complex and famous example of this system was the German Schlieffen Plan.

Recruitment for the sultan’s jihad (holy war) near Tiberias. Although the sultan called for a jihad against the Christian allies in the autumn of 1914, it failed to attract many followers. The Turks and Germans had hoped to rouse the Islamic peoples of Egypt, India and Caucasia against their British and Russian masters.

Unfortunately for the Ottomans, they were in the middle of a massive effort to restore their shattered armies and were quite unready for mobilization. General staff planners thought that it would take about 21 days but, in many cases, mobilization took between 30 and 45 days. Although the army’s regiments and divisions had sufficient manpower, they lacked artillery, machine guns, and supplies of all sorts. To make things worse, the empire’s inefficient railway system was in an abysmal condition andserviced the economic interests of foreign entrepreneurs rather than the needs of the military. Significantly, except in Thrace, the railways did not extend to the frontiers, making the concentration of forces problematic.

In September the army began the process of moving its units from their garrison cities to their war stations in Thrace, Caucasia and Palestine. In a terrible strategic error, no forces were sent to Mesopotamia, which was actually denuded of two of the four infantry divisions stationed there. Concentration took over 60 days and some units marched on foot over hundreds of kilometres to reach the frontiers. European military attachés observed the slowly unfolding mobilization and concentration, which appeared to confirm conventional negative opinions regarding the efficiency and capability of the Turks. British observers characterized the Ottoman Army as ‘not a serious modern army’ and its soldiers as clumsy, dull witted and ‘very much afraid of the enemy’s bayonet’. These opinions would be proved wrong in the coming year.

As the empire was not yet at war, this slow concentration of forces gave the general staff more time to consider the strategic situation and alter its defensive plans. In early September, under the direction of the capable German colonel Fritz Bronsart von Schellendorf, the staff began work on new plans for offensive operations in the Caucasus and Palestine. Germany certainly pushed its Ottoman partner into operations that its army was unprepared for. However, the relentlessly aggressive but inexperienced Enver Pasha, who was now in charge of the war effort, enthusiastically endorsed the German ideas. The result, contrary to military doctrine, threw nine divisions against the Russians in the Caucasian winter and four divisions against the British across the waterless Sinai Desert, while 18 of the army’s best divisions sat idle in Thrace.

Throughout the autumn of 1914, the Ottoman Army relentlessly trained its soldiers in the battlefield skills necessary for survival and success in combat. This process was characterized by rigorous physical training and long marches through difficult terrain. As the proficiency of the men increased, the Turks conducted combined-arms training that linked infantry to artillery and stressed achieving fire superiority. When the soldiers were not marching, they were digging trenches. Such lessons had been learned in the Balkan Wars and the Turks took them to heart. By late October the army was very much improved, a condition that was noticed by the Western military attachés in Constantinople. Naturally, they attributed this to the presence of the German Military Mission, but in fact very few Germans were actually stationed with Ottoman troops.

Turkish troop columns marching out to drill. The Ottoman Army conducted large-scale peacetime manoeuvres in the years leading up to the outbreak of World War I. The empire’s soldiers were well trained, hardy, and inured to harsh condition. They were also highly mobile and capable of executing fast and difficult marches.

Events soon overtook the Turks, as the Russian declaration of war took the uninformed general staff by surprise. In the meantime, both the Russians and the British, anticipating that the Ottoman Empire would enter the war on the side of the Germans, had positioned forces for immediate offensive operations against them. On 3 November the British fleet cruising off the Dardanelles (hoping that its quarry the Goeben would sortie) shelled the Turkish forts at the entrance of the straits, which merely served to alert the Ottomans as to the weakness of their defences. In the Caucasus the Russians launched a powerful attack on 6 November against the Koprukoy lines northeast of the fortress city of Erzurum. The Turks were largely unprepared for this and lost thousands of men, before restoring the situation with a vigorous counterattack.

On the same day the well prepared British landed troops of the Indian Army in the Shatt al-Arab. There had been much discussion in the autumn between the Admiralty and the India Office over the need to protect British access to the oil fields owned by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, on which the Royal Navy was rapidly developing dependence. As a result, Lieutenant-General Barrett’s 6th Indian Division (the Poona Division) was designated as Force D and put on ships in the Persian Gulf to await developments. The mission of Force D was simply to secure the oil terminal and tanks at Abadan. The Ottoman military’s failure to properly garrison Mesopotamia was probably its worst mistake of the war, and was the result of pre-war thinking that could not and did not envision its historic friend and protector, the British Empire, as a threat. Consequently, Mesopotamia was left almost entirely unguarded and its pre-war garrisons were sent elsewhere.

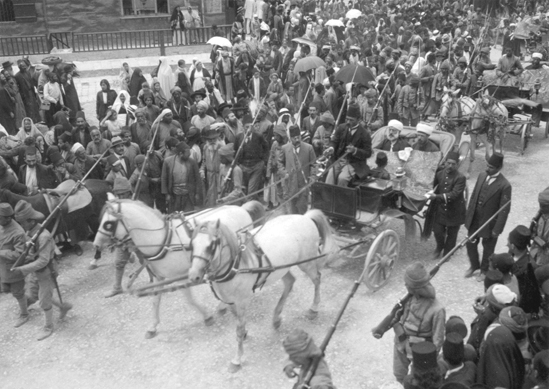

A holy carpet brought to Jerusalem by the Sharif of Medina. The Grand Mufti and Sharif are riding in the carriage. The Turks held the holy cities of Mecca and Medina throughout the entire war. Although not militarily significant, these centres of Islam had great spiritual and political value for the Ottoman Empire.

Barrett’s Indians attacked the old Turkish fort at Fao, which was garrisoned by a mere 400 men, and easily took it. There were hardly any Ottoman soldiers in the area, and those present were either brushed aside or quickly surrendered. Encouraged by the terrible Ottoman showing and failure to mount effective opposition, the enthusiastic British commander, Brigadier W.S. Delamain, seized Basra on 20 November and advanced to Qurna two weeks later. By December the British had secure foothold in lower Mesopotamia with an entire infantry division, and had begun to build up a river boat flotilla. This lodgement would prove irresistibly seductive for the Indian Army’s high command, and would lead to problems within a year.

‘The imperative need of direct control of a reasonable proportion of the supply of oil fuel is required for naval purposes’

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, memo to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, 1914

The outbreak of war was a disaster for the Ottoman economy. Almost everything made by machine was imported from Europe, as well as metals, coal and medical supplies. Moreover, the economy itself relied not on its weak internal lines of communications, but on a robust coastal trade to carry goods throughout the empire. In November 1914, the ever-present British Royal Navy clamped a rigorous blockade on Ottoman seaborne trade, which combined with the efforts of Russia, Serbia and the neutral Christian states of the Balkans effectively isolated the Turks. This situation continued for the first year of the war, until Germany crushed Serbia and re-established communications with the empire.

The early campaigns of the war were disastrous for Ottoman arms. This was the result of not only poor planning, but poor political policy and inchoate war aims as well. The provocative Black Sea raids brought the Russians and British into the war, and they were able to attack the unready Turks immediately. The Turks were mauled by the Russians at Koprukoy and their dismal showing in Mesopotamia allowed the Indian Army to gain an easy foothold at low cost. Mesopotamia would soon become a running sore for the Ottoman war effort.

Unlike the Europeans, whose diplomacy was closely tied to their war plans, the Turks lurched unsteadily into the war. There were points in the autumn of 1914 when it might have been possible for the Entente Powers to convince the Turks not to fight. Unfortunately, the Secret Treaty with Germany was not so secret by that time and the Allies, who did not know its terms, thought that it tied the Germans and Turks together in an offensive alliance. As a result, rather than actively pursuing diplomatic solutions, Entente leaders and planners powerful personalities conspiring in Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire might never have entered the war at all.

Unlike the Europeans in that dangerous and odd summer of 1914, who enthusiastically put on their uniforms and eagerly went off to war, the mass of Anatolian Turks were indifferent or even opposed to the war. In the Balkan Wars, many of the casualties were ethnic Turks, and a civilian population numbering in the millions was evicted from territory it had owned since the fifteenth century. Anatolia and Thrace suffered as a consequence, as the empire tried to assimilate millions of Muslim refuges from the Balkans. While a small part of the Ottoman elite welcomed the war, there were no spontaneous outbursts of patriotic fervour as there were in the European countries. Furthermore, about half of the empire’s non-Turkish population had nationalistic interests overtly hostile to its continued existence, and welcomed the opportunity to throw off the yoke of Ottoman domination.

Overall, the entry of the Ottoman Empire into World War I was a significant strategic victory for the Germans. It cost them almost nothing and suddenly opened up three land fronts with the Entente, as well as forcing the Royal Navy to conduct a blockade in three seas. Later, more Ottoman fronts would open up at Gallipoli, Salonika and even in Galicia and Persia. By the end of the war, the Germans would have committed some 50,000 men to the Ottoman fronts, while the British and Russians alone would commit over three million. Indeed, the Turks punched well above their weight and, over the next four years, absorbed massive amounts of Allied strength and resources. There were other problems for the Allies as well. Among the British there emerged two competing camps concerning the strategic direction of the war: ‘Westerners’ (who believed in the primacy of the Western Front) and ‘Easterners’ (who believed that the war was best fought in peripheral theatres to knock out Germany’s allies). For the Russians, the loss of access to the Mediterranean through the Turkish straits created an immediate and compelling problem with their grain exports and reciprocally with the importation of war matériel. While the Turks were not able to win the war for Germany, they were able to weaken significantly or divert the war efforts of two of Germany’s three main opponents. This in turn would have a profound impact on the course of the war.

Austrian artillery commanders entering Jerusalem. As the war progressed greater numbers of Germans and Austrians were sent to assist the Turks. Most of these soldiers went to Palestine. By 1918 up to 20,000 German and Austrian soldiers were serving in the Ottoman Empire.

A soldier of the Indian Army. After Gallipoli, the Indian Army made up much of Britain’s fighting strength in the Middle East. By 1918, Indian infantry in particular emerged as a potent force; indeed, the imperial armies that seized Mesopotamia, Palestine and Syria were mostly Indian.