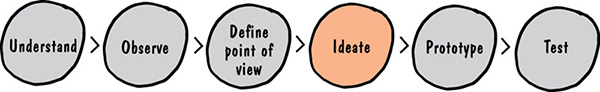

1.7 How to generate ideas

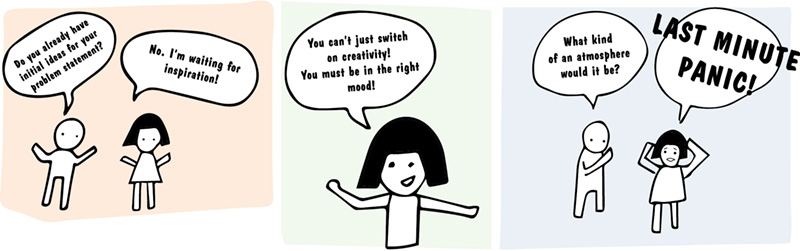

Without ideas, no new products! The importance of finding good ideas at the right time is enormous, putting both participants and workshop facilitators, whose job is to tease out ideas from attendees, under pressure.

We know from studies that groundbreaking ideas don’t always emerge during a brainstorming session; sometimes, the creative spark leaps while you have a shower or scribble something on a napkin. This is why creative companies give their employees more and more leeway to allow for this type of intrinsic inspiration to happen; for instance, in the form of workdays on which employees are allowed to do whatever they want. The only condition is for them to report back what they have done.

However, often the milestones already have been set, and as product developers or engineers we are in no position to explain to the boss that we want to spend the next four hours in the shower because the chances of hitting on great ideas are better there. So we need methods and tools of structured ideation.

Peter in particular is under a lot of pressure due to deadlines. He must deliver up creative results and, consequently, get his team to cough up creative outputs and put people in the right mood at the touch of a button. Lilly knows from experience that some factors must be met for this touch of the button to be effective. The following credo actually seems too banal and childish to her: “A good mood is the #1 prerequisite.” Despite this, she’s convinced that the potential of shared ideation can only unfold when a casual, relaxed atmosphere prevails. Only then can attendees engage in a search for ideas on a broad basis. The switch to a different or new environment alone can change the mood. If the meeting takes place week after week in the same conference room that is associated with some boring statistics, it is not conducive to a good atmosphere. So why not move the workshop to another room, outside, or even to the closest bar?

Before beginning with any brainstorming, people must laugh at least once. A warmup that makes participants smile helps. From our experience, it’s best when they smile at one another.

Thinking in hierarchical structures is a hindrance to free and unfettered ideation. An apprentice does not want to make a peculiar impression on his boss when expressing a fanciful idea.

For this reason, we are encouraged to point out that the assistant and the accountant, the CEO and the marketing officer of the company, can all make an important contribution in the process of ideation. If participants do not know one another, so much the better! Not having general introductions before the brainstorming session, which would include announcing who has which role, has proven useful indeed. A nonbiased dialog is of great value.

When we feel there is a steep hierarchy in our company, we can try out the reverse approach: We form a team only from trainees, for instance, so they will have the opportunity to raise their profile and show others their creative potential. In the next workshop, the groups will then almost certainly mix at their own initiative.

The beauty of brainstorming is everybody is given the opportunity to come up with good ideas, no matter which function or role he or she has.

Brainstorming rules are numerous. Our top three are:

Creative confidence

We express all ideas that come into our heads, no matter how silly they might appear to us. Maybe the next person can base another idea exactly on our “silly” contribution. For this to work, we need the relaxed atmosphere just described.

Quantity goes before quality

Very, very important! The point of this phase is to fill the hat with as many ideas as possible—evaluation comes later. We resist the temptation of being satisfied with the first good idea. Maybe an even better idea is only five minutes away in our brainstorming session.

No criticism of ideas

Under no circumstances are ideas allowed to be criticized during this phase. The evaluation of the ideas takes place later in a separate step.

Quite conventional ideas usually mark the beginning of a brainstorming session. Their novelty value is low.

Peter has had the experience of some of his colleagues coming to every workshop with a fixed idea of how the solution might look. During the brainstorming session, it is hard to pull them away from these fixed ideas, and they generate little that is new. For this reason, Peter always holds a first session at the beginning, which he refers to as the “brain dump.” All attendees have the opportunity in this session to dump their ideas so they are open to new things.

The actual search for ideas only begins in the second step. Peter encourages the participants to break out of their usual thought patterns so they can come up with some “wild” ideas. He uses two specific tricks; here’s how we implement them in our workshops:

1) When we moderate a workshop with several groups, we can shape the search for ideas as an internal contest. We stop the brainstorming session after halftime and request that the groups state the number of collected ideas.

For the individual teams, this is an incentive to catch up, so they will inevitably have to venture in the direction of “wilder” ideas if they have undermatched the creative performance of the other groups. This approach allows us to see which group is wrestling with difficulties. If one group is far behind in their number of ideas, we watch to find out exactly what inhibits the team. Usually, it turns out this group has—against instructions—begun to discuss and evaluate the ideas.

2) We have the groups present the two best and two dumbest solutions they have generated. This moment is a valuable experience for every group. First, the task will induce a few giggles, which is quite a help for creating a positive atmosphere. Second, and far more important, now a debate is launched on whether some of the ideas are actually as dumb as had been assumed at first. Every dumb idea has potential! When we know how to reverse the idea successfully into something positive, we will gain valuable perspectives with a guaranteed novelty value.

Problem reversal technique

The problem reversal technique is Lilly’s favorite method when she asks students to generate ideas for something but they don’t really have any desire to join in. Lilly reverses the question and asks, for example, “How would you prevent creativity on your team?” The problem reversal technique stimulates creativity and gives participants the opportunity to have fun with a topic. In a second step, every negative statement is reversed into a positive one.

We must emphasize, though, that this method is less suitable for finding new product ideas. The reversed question, “What would something have to be like?” often results in a requirements list instead of ideas. We have nonetheless had good experience with the problem reversal technique; for example, for the revision and/or improvement of service processes.

Requirements versus ideas

Lilly learns that students in the technical area in particular have great difficulties finding “real ideas.” They have a hard time differentiating between requirements and ideas. In a brainstorming session for a new headset, participants wrote “ergonomic,” “lightweight,” and “user-friendly” on their Post-its. Those participants coming from business administration wrote down words such as “cheaper” or “cutting-edge design.” At this point, Lilly interrupts and explains that these things are not actually ideas but requirements for the product. Of course, we must also be clear about the problem for which we want to generate ideas. In this case: How might we communicate in the future without cell phones? The terms “ergonomic” and “cutting edge” do not entail a solution to the problem. An idea would be that, in the future, the electronics would be implanted under the skin to communicate worldwide. A somewhat less abstract idea would be to integrate the communication in accessories and clothing, such as with Google Glass.

Depth of ideas

To explain the levels of the depth of ideas and the term “requirements” better, we use the following model: We imagine we are standing in front of a ditch and want to get to the other side.

1. What is the problem? (level 1)

A ditch cuts off this side from the other side.

So our problem is that we must get to the opposite side somehow. We start brainstorming with the question: How can we get to the other side? “Safely,” “in one piece,” “dry,” and so on, are not ideas but the requirements for the solution. They don’t help us in this situation.

2. The brainstorming question (level 2)

The formulation of the brainstorming question is crucial and largely determines how many ideas can be generated or how greatly the possible solution space is expanded. Depending on the question, we restrict and channel the solution space or else expand it. The following formulations illustrate this: “What could we lay across the ditch to get to the other side?” versus “How can one overcome a physical barrier such as a ditch?”

3. Possible solution ideas (level 3)

We might “fly,” “build a bridge,” “beam ourselves,” or “fill the ditch with so much material that we can walk across it.”

4. Idea variants (level 4)

Any number of variants can evolve for each of these ideas. In a second brainstorming session, the question might be: How many ways are there to fly? “With an airplane,” “with a flying bicycle,” “with bird wings,” “like in the Red Bull ad,” “by pole vaulting,” and the like.

If one group finds it hard to get away from requirements, it is advisable to have them build rudimentary models of their “ideas.” This will make it mandatory for requirements to be implemented as an idea.

Tips for depth of ideas:

- We formulate the brainstorming question so it matches the solution space we want to open up.

- We can still adapt the brainstorming question during a workshop.

- The solutions from level 3 can be consolidated in a morphological box; more variants of partial solutions are conceivable.

- If a group has a hard time advancing to level 3, the instruction to translate the ideas into a physical prototype is often quite helpful. It forces the participants to become more specific. Implementing a physical model in a “user-friendly” way will help them engage in level 3.

“Prototyping”—building an idea as a physical model—is another creativity technique. The diversity of the provided material determines whether more ideas will emerge or not. The more odds and ends are available, the better it is. A balloon that’s been discovered summons up the idea that something could be flexible and stretchable; a piece of cord reminds a participant that the thing might be portable.

The rubber dog in the prototyping material box:

More or less by accident, Lilly threw a rubber toy dog into the prototyping box. When the participants in the brainstorming session were tasked to translate their ideas into physical models, one of them found the toy and was highly amused by it. He started to spin ideas: “The dog could do this and that in the machine,” whereupon his team members joined in and came up with more ideas. The team had a lot of fun with the dog, which enabled them to break out of their habitual thought patterns and reflect upon things they had thought little about up to now. Until the very end, the dog contributed materially to the successful outcome. Since then, it has been an integral part of Lilly’s prototyping box that she brings along to the workshops.

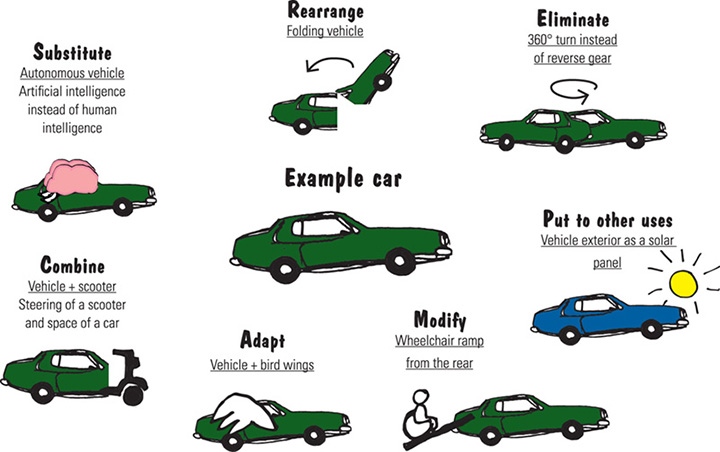

SCAMPER is a further development of the well-known Osborn checklist. Alex Osborn, a brainstorming expert, developed in collaboration with Sidney Parnes one of the first approaches to the creative problem-solving process. For ideation, the Scamper method uses—along with brainstorming—a list of questions that should provide food for thought toward solving the problem. In our experience, it is important initially to see an example and then go through the detailed questions. SCAMPER is an acronym and stands for the terms:

SCAMPER = Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to other uses, Eliminate, Rearrange

SCAMPER is useful when we would like to stimulate creativity and find even more ideas. Basically, SCAMPER can be used for nearly anything: for products, processes, systems, solutions, services, business models, or ecosystems. In the event that individual questions or elements are not quite suitable or obvious, that doesn’t matter for the application. We simply leave these questions out.