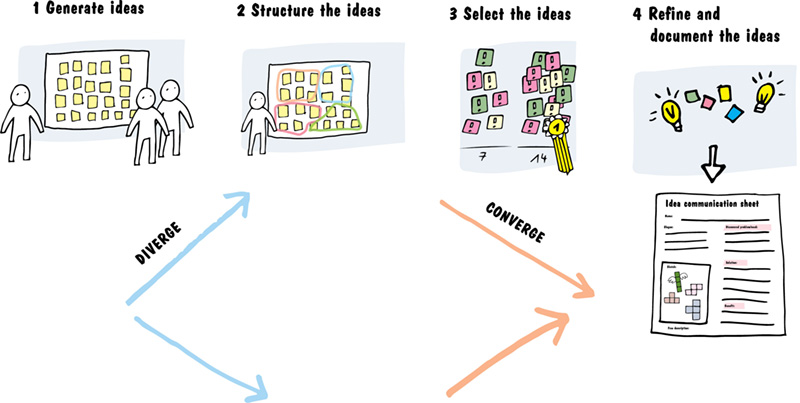

1.8 How to structure and select ideas

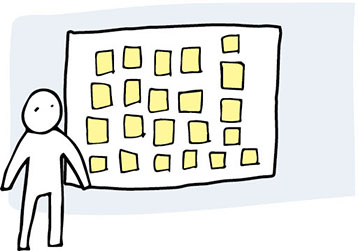

When we apply various types of brainstorming, we amass many ideas. In addition, we have consciously encouraged the teams to generate as many ideas as possible. Peter and Lilly are aware of the phenomenon: Once the team’s initial reluctance has been overcome and a positive mindset has set in, ideas keep cropping up in rapid succession. Often, the screens, windows, and walls are not big enough to place all the ideas.

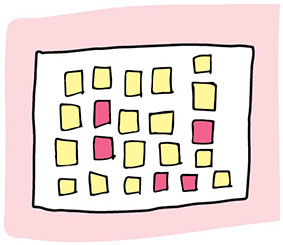

The agony of choice. Selecting ideas is a real challenge. For one, each one of us interprets the drawings, words, or short texts on the Post-its differently. Second, there are ideas whose basic thought goes in the same direction, and ideas that solve a completely different problem than originally intended.

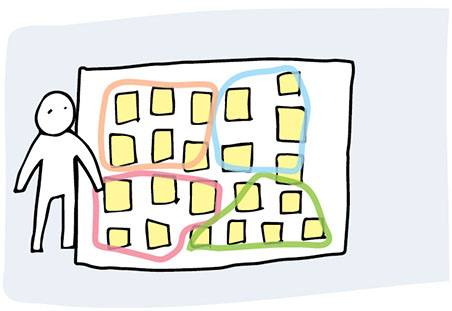

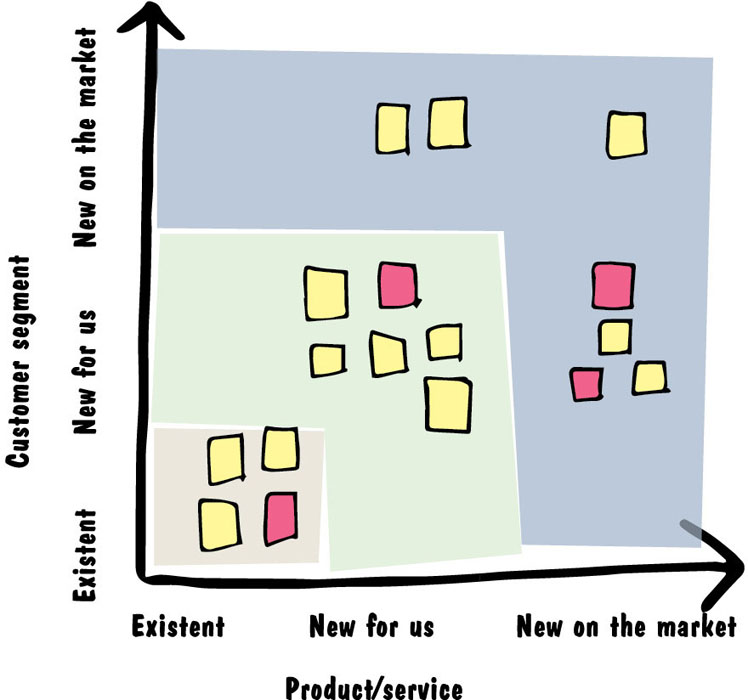

We recommend performing a sort of clustering initially. This can be done in different ways: Either the facilitator sets the framework, or else the teams themselves conduct a classification that seems the most suitable to them.

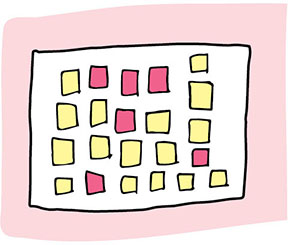

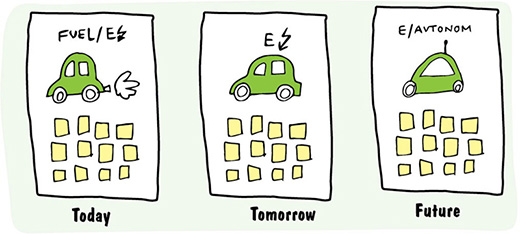

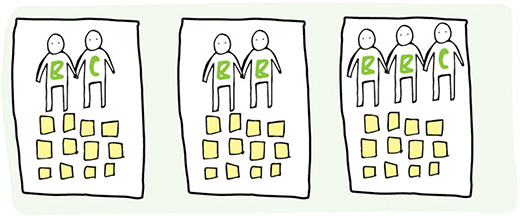

The examples show that ideas can be grouped, assigned, or simply described by an umbrella term. The way is the goal, and the discussion about a meaningful classification in itself results in everybody having the same understanding of the ideas in the end. Depending on how solid the understanding and how refined the degree of detailing is, ideas can be selected directly or undergo further analysis, specification, and structuring. There are various possibilities for evaluating ideas and clusters. Having participants vote for ideas by placing adhesive dots on them is a simple way to do it. The vote is quick and democratic.

Structuring, such as with concept maps, improves the clarity of the ideas and makes it easier for the team to plan the next steps and tackle them in a focused way. Once the idea has been selected, the next step is to present it in a way appropriate for the target group. Again, there are various possibilities for this, such as creating a communication sheet of the concept ideas.

A) Matches the question

B) Exciting

C) Out of scope

D) Today – Tomorrow – Future

E) B2B – B2C – B2B2C

F) Incremental versus radical

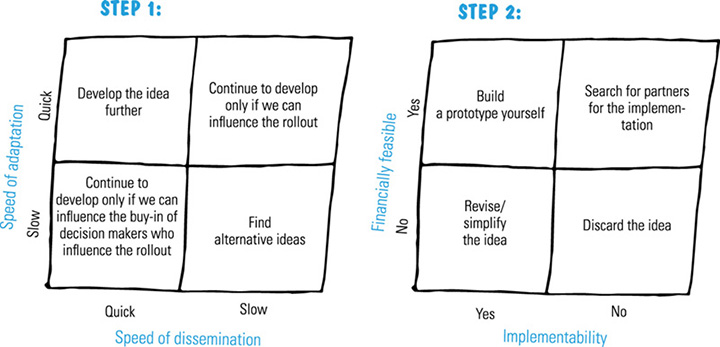

G) Stepwise selection using the “speed of dissemination and implementability” matrix

The first step of this two-tier procedure focuses on the speed of dissemination and the speed of adaptation. Especially in a political environment—which prevails at Peter’s company, for instance—it is useful to consider the decision makers and one’s own influence on the potential rollout. The best ideas are characterized by rapid dissemination and fast adaptation. In a second step, the implementability and financial feasibility are investigated. This results in implementation alternatives or indications of the functional scope.

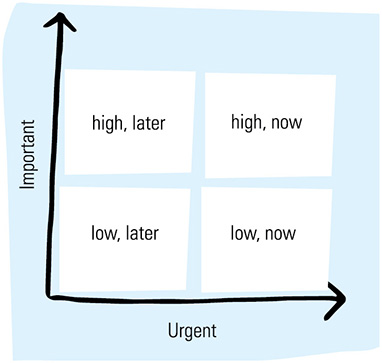

H) Selection based on the criteria of “important and urgent”

This matrix is particularly suitable when the search is for which measures to use.

We show the urgency on the x-axis and the importance on the y-axis. Then we discuss with the team which measures must be allocated to which quadrant. Once all measures have been entered, we can enter the to-do’s, including the respective responsibilities, and determine milestones.

We all know the phenomenon of criteria being developed in large organizations to select potential ideas. These criteria enable a large number of teams to develop innovations in a more targeted way. Often, the criteria act as a kind of guardrail or specify certain financial goals. In general, such criteria are inhibiting, but because they do exist in reality, we should discuss them. If the criteria are not known within the framework of a well-defined strategy and vision, it is useful to ask some key questions:

- What might the vision be?

- What are the personal preferences at management level?

- What is our enterprise’s culture, its values, and and sense of morals?

- Which growth areas have already been defined as part of a strategy discussion?

- What is the financial contribution an idea must yield as a minimum?

- What are the customer needs and trends on the market?

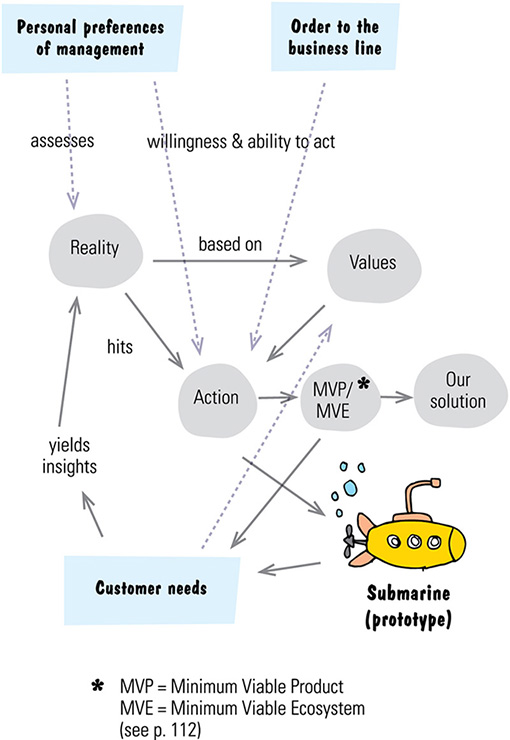

When defining criteria, it is important to be aware of reality. The potential market opportunity can be as great as it may be, but if the decision makers (e.g., top management) don’t cotton to it, the idea will fail. At the least, when financial resources are allocated, we will be confronted with this situation. As illustrated, a selection via the dual matrix with the dimensions of speed of dissemination and implementability can be useful.

The values a company stands for are equally important. If it goes against the moral grain of a company to use customer data from digital channels for other business models or to sell it profitably, such ideas will have little success. Defining of these and other criteria at an early stage has at least the advantage that the waste of resources is reduced and effectiveness is boosted.

But we ought to try everything in our power to overcome such restrictions. In our experience, “submarine” projects have proven useful: projects that are initiated on the q.t. with a small number of dedicated employees and “go to the surface” only once the initial results were worked out in prototype form and have won over the decision makers.

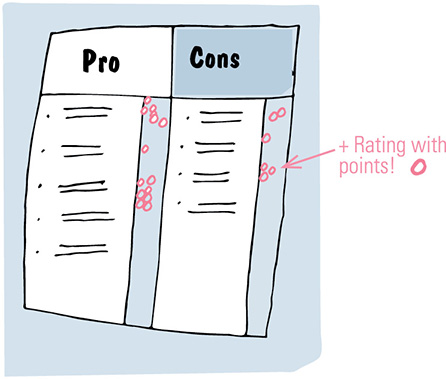

Any type of structure can be depicted as a poster; for example, as a simple pro-and-con poster. The goal is to visualize the collective intelligence of a team or capture a mood. For example, we query pro and con arguments on a subject in a poster form and then have participants rate them. Lilly uses this variant to obtain quick feedback about the course from the participants at the end of her design thinking event without having to get into prolonged discussions.

For scheduling, we can draw the poster in the form of a timeline. Let’s take the planning and iterative creation of The Design Thinking Playbook as an example. Again, we had the “courage to drop”! The party atmosphere at the end of the project was quite motivating for editors and experts. How we can use such elements otherwise and visualize them in a target-oriented way will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2.3.

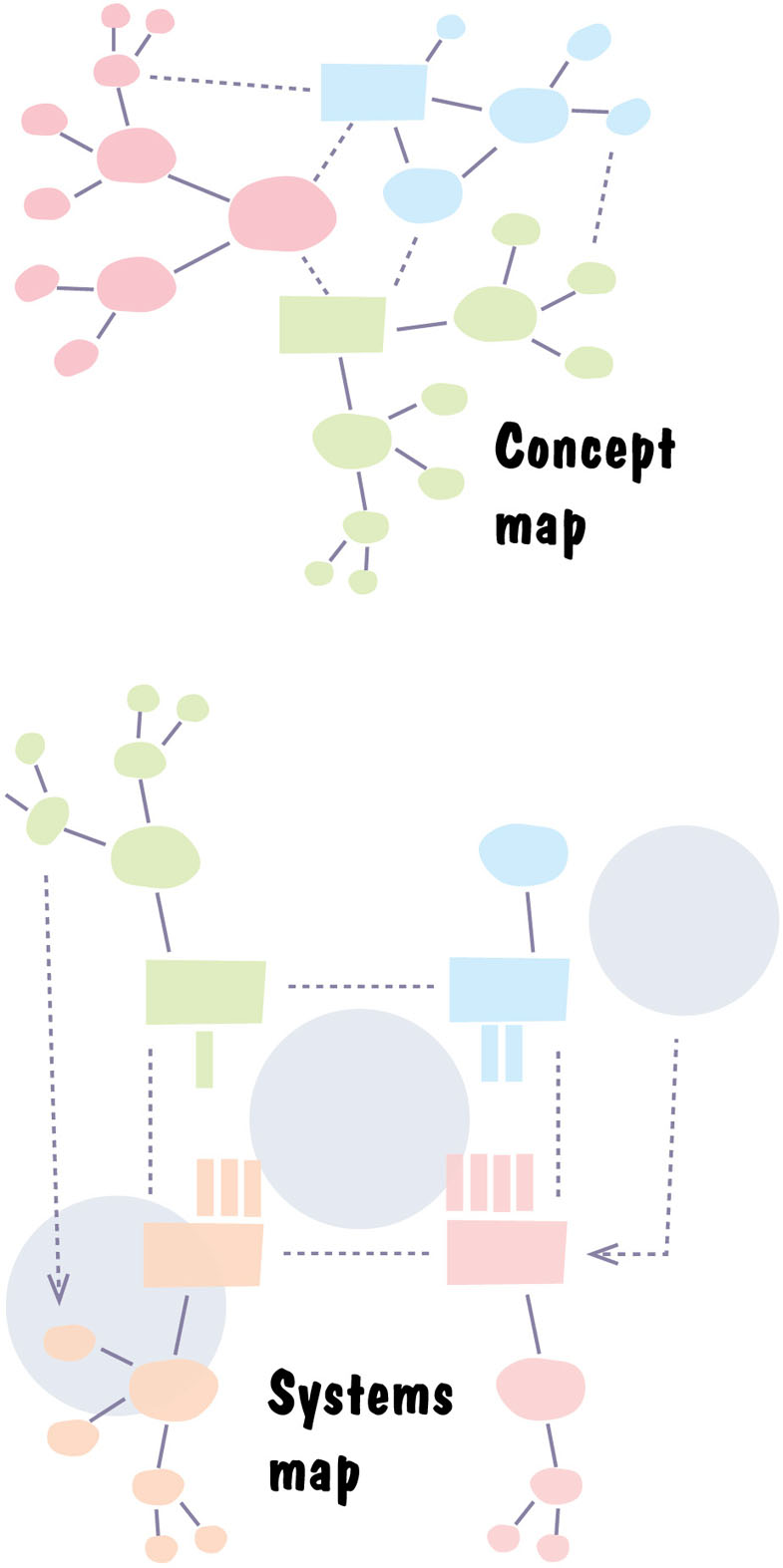

A concept map is basically nothing more than the visualization of concepts that shows us the correlations. Thus a concept map in a figurative sense is the graphic depiction of knowledge and an excellent means for us to bring order to our thoughts. The depiction of the concept map is freer than that of the better-known mind mapping.

In the mind map, the key concept is written in the center and then built up from inside to outside. Thus it looks like a tree: branches on which terms are written go off from the key concept. Hence the mind map is more a means for brainstorming. It helps to bring order to the discovered points but it doesn’t show the correlations among them.

A concept map can start from several key concepts. Often there are cross-connections between the branched concepts, similar to a road network. For this reason, the creation of concept maps takes more time than that of a mind map. In our experience, at least three new creations or restructurings are usually necessary to get to a good result.

As the name suggests, a systems map is a visualization of the system. The various actors and stakeholders as well as the observed elements are sketched. Interrelationships and influences can also be depicted. In so doing, an iterative adaptation and detailing takes place. Typically, you go from the rough to the detailed (i.e., top-down). Thinking in variants is also an important element. In a systems map, material, energy, money, and information flows can be depicted. A systems map helps to understand and visualize the problem.

We will address the topic of systems thinking in greater depth in Chapter 3.1. Chapter 3.3 will deal with business ecosystem design.

Other concepts, such as the giga map, will also be investigated more closely. A pragmatic description of a giga map would be “a big messy map of a big messy thing.” It is also a stripped-down form of the systems map, while following the basic idea of the concept map. Giga maps can help us draw up a holistic conception of a specific task, for instance. In a final version, the giga map helps to communicate the treatise. But usually, largely owing to its complexity, it is only understood by those who created it.

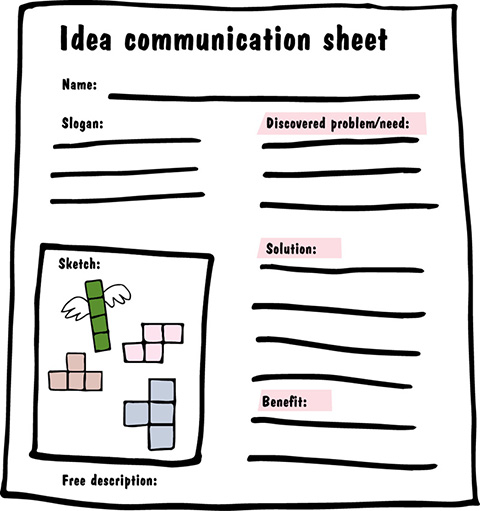

We work frequently with teams all over the world in major projects and organizations. The simple and clear documentation and communication of ideas is, hence, extremely important. Communication sheets on the concept ideas are a good way to achieve clarity. Ideas can be shared easily with such templates. Moreover, ideas become tangible, and possible misunderstandings are minimized.

With the compilation of communication sheets, we achieve

- the visualization of the problem and the situation,

- an improved understanding of the problem and idea,

- a better understanding of possible influences on customers and users,

- order to our thoughts,

- the recognition of approaches to the solution, and

- the documentation, summary and depiction of our knowledge.

We recommend this simple procedure for giving structure to the ideation process. First, after the ideation, bundle the ideas into clusters and structure them. Then, select the most important ideas or clusters and refine them; last, document them.

The ideas can be selected according to the needs of our persona or according to actual use.