2.1 How to design a creative space and environment

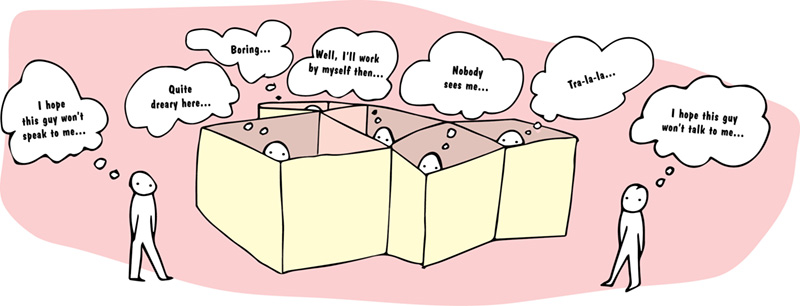

Our personas are always confronted with the question of where they should practice design thinking at their university or in their company. The premises of most companies and universities were neither planned nor staged as creative spaces, nor are they suitable for such use. The majority of them are filled to the gills with bulky furniture, thus blocking any creative energy. In particular the tables prompt people to work individually or else work on their laptop. In the best case, employees or students sit around a table, which encourages, at most, an exchange of ideas, but does not generate any shared common creativity.

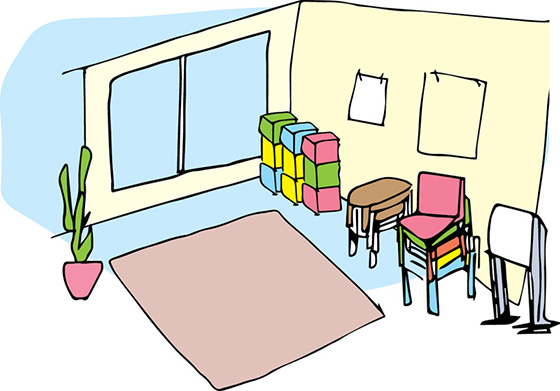

The good news for Peter, Lilly, and Marc is that nearly every room that has plenty of natural light and space (preferably about 5 m2/55 sq ft per participant) can be quickly reshaped into a creative space. The goal is to gain as much freedom as possible for creativity to unfold. We do best by starting with redesigning the environment and implementing the first prototype of a creative space.

At the bank where he works, Jonny finds meeting rooms galore, but only very few of them have the necessary flexibility to foster creativity. He has brought up the need for such a space several times already. In the end, he succeeded in convincing his boss, while having lunch together, to venture the experiment of a creative space. The room he gets for it is not optimal, but the old coding machines that were stored there had to be disposed of sooner or later anyway.

Start with emptying the room, because less is more in this case. Only in an empty space can something new evolve. We consider how many people are to be creative in it and put in one or two additional chairs, stackable ones if possible. Flexible and stackable material is better suited than inflexible and rigid stuff, because stackable furniture allows you to create even more space if the situation calls for it.

The design of the space must take into account whether the creative space must accommodate a project team of 4 to 12 members working on a project for weeks or months, or 8 to 25 participants who sit over a topic only one or two days.

For feedback providers, the space can be furnished with additional stools or textile cubes. The textile cubes can also be used as seat stacks and staged beautifully. Feedback sessions last only a couple hours, not days, so simple seating accommodations are quite reasonable.

The next important thing is to think about the material to be used for building prototypes. You can use a caddy on wheels as a container, filling it with numerous multicolored whiteboard markers and Post-its in various colors and sizes as well as adhesive dots. Another variant is to keep everything in transparent boxes. Such boxes are particularly advisable if you often want to travel with your prototype material or switch rooms.

We’ve found it useful to provide some prototyping material as early as at the beginning of a workshop (e.g., playdough, Lego bricks, string, colored sheets of paper, cotton wool, pipe cleaners, etc.) and lay it out on the table in the room. Masking tape to hang flip charts is always useful—like other prototyping material, it can be purchased at any DIY store.

Depending on the size of the space, we still need one or several flip charts on rollers. If no flip charts are available, we can fasten individual sheets of the flip chart to the wall with nails, or simply paper the walls with individual sheets of paper and masking tape.

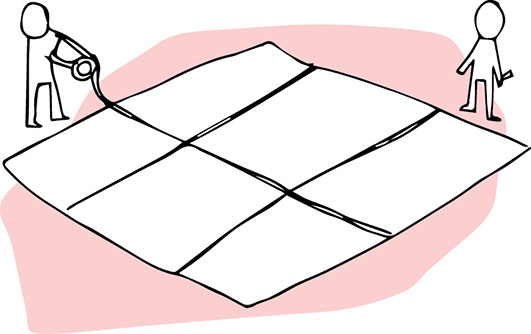

As an alternative to flip chart paper, large paper rolls can be used. Pieces can be either cut by hand or torn off with some integral device. The pieces can then be stuck on the wall with masking tape. From our experience, it’s always good to have some extra flip chart paper. Nothing is more annoying and inhibiting to the creative flow than when we run out of basic material—this includes functioning whiteboard markers.

Usually, any smooth walls are suitable for working on flip chart paper and hanging it up. Should the walls be very uneven, several sheets on top of one another should be used in each case, so they can be written on legibly. As an alternative, you can work with Post-its in such a case, which can be written on prior to placing them on the flip charts.

If large paper surfaces are needed and XXL sheets are unavailable, we glue together any amount of flip chart pages with the masking tape on the back to build huge creative surfaces. Such empty creative spaces, even if they refer “only” to paper, are important because creative energy needs room to unfold. It goes without saying that the flip chart paper is used on the side with the squares.

Writable walls, window panes, or glass walls are excellent for directly writing and painting on them with whiteboard markers.

If, for some reason, there isn’t enough space on the walls, whiteboards and maybe pin boards on rollers, which can be moved around the room, are the right choice. Design thinking professionals use flexible whiteboard walls (in the HPI design) on rollers for their work.

If you’re looking for a table in the creative space, it is extremely practical to use lightweight furniture that can be easily moved. Rollers are a plus.

With respect to the tables, choose a more organic, stimulating shape over a rigid rectangular one. The table should be placed free-standing in the space because, as described, all wall surfaces will be included in the creative work , so ensure there is sufficient clearance to work and move around the room.

Instead of on the table, we can simply put the required material on chairs or stools that are not needed. This uses less room, and we have more free space to move in. For the creative process, we don’t arrange the chairs around a table, but instead distribute them freely in the room. When they don’t sit stiffly at the table, participants stay more agile, both physically and mentally, which has an enormous influence on the creative process and the results.

If a coatrack is needed, it’s best to use a stand that can quickly be moved for different settings and does not interfere with things in the space. As an alternative, you can put it outside the room. It is also important that the bags and other luggage of the participants not be put on the floor along the walls but instead on top of or underneath unoccupied chairs. This is the only way to work on the walls free of hindrances and for the results to be presented and seen later.

After the initial experience with the prototype of a creative space, we must now develop it further and improve it based on what we have learned.

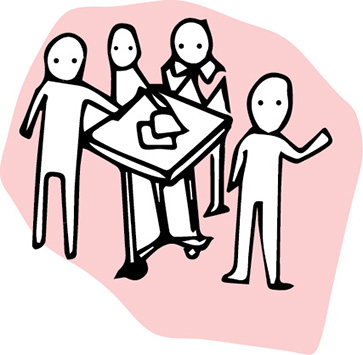

The next level of a professional creative space has whiteboards attached to the walls already. These are good for visualization. Important inputs and papers can be attached to them with magnets (extra-strong magnets for posters and heavier paper). Chairs are available in different colors, and stackable versions are preferred. The tables should have rollers, if possible, and should be foldable, so they’re never in the way. Different working positions support the creative flow. As a supplement, tables on rollers can be very inspiring depending on the kind of workshop. Square measurements have proven useful; the tables used in the Design Space at the Stanford d.school have this shape. Four workshop participants can group around these tables, and enough space is left to sketch something or for prototyping.

More unusual material wouldn’t go amiss for prototyping (Styrofoam, colored wool, wood, balloons, fabrics, cardboard, and the good old extensive collection of Lego bricks all find a new home here). Everything handicraft shops have on offer and that can be put into prototypes is usable. Lilly’s favorite prototyping material is aluminum foil. Any shapes can be quickly created from it, and pieces can easily be made smaller without using scissors. There are no limits to the imagination—with time, you will realize that simple materials in particular have the potential for great prototypes.

With a more ample budget, the walls can be painted in colors that immediately create an inspiring environment. Colors such as orange, blue, or red are welcome; for example orange stands for creativity, flexibility, and agility, and blue for communication, inspiration, and clarity. Colors and patterns on usually barren floors are outstanding for inducing creativity. Carpets of all sorts, PVC, homey wood, or paint can be used, depending on the suitability of the subsurface.

Although you should set no limits to creativity, you should keep the industry, the type of enterprise, and the prevailing corporate culture in mind. The space can be enriched in a playful way with unusual and crazy things like rubber boats, hammocks, or shower curtains used as separation. Such objects can have an inspiring or consciously disruptive effect. This “disruptive” function of a creative space that dissolves or destroys what exists is quite conceivable in order to put things in motion. It’s up to us and our sensitivity with respect to the other teams, our sponsor, or the decision makers to choose the right setting. Our tip: Begin with a low profile and observe the reactions of the environment carefully before you go too far with your creativity.

We can’t tackle the challenge without some courage. It’s not easy to change a work environment successfully. As with any innovation, you’ll likely encounter resistance. Sometimes, such resistance points at real weaknesses in a concept; sometimes, people are simply suspicious. Any resistance must be taken seriously and accounted for in the implementation process.

A creative space can be designed jointly as part of a team development process. After all, the participants must feel comfortable and identify with their space. By the way, this is why employees often don’t feel comfortable in stylish rooms: because their wishes and needs have not been taken into consideration sufficiently or at all.

Simple “goodies,” such as active loudspeakers for a little music, might also be well received, because music can support the creative flow (e.g., soft music playing in the background during design sessions). The caddy can hold a coffee machine and an electric kettle for tea. Bottles of water, cups, and brain food such as nuts and dried fruits should be available in the room.

As an alternative to a small screen and a projector, teams can work with slightly larger screens if the available space allows it. Again, a version with rollers is recommended, so it can be pushed aside when not needed.

How exactly should we now proceed? First, we develop a common understanding of the idea, or the order and client. It goes without saying that we consider the scope, possible framework conditions, and any restrictions. This way, we arrive at an initial, roughly formulated design challenge that is open enough and does not contain any solution in its description.

We plan the estimated one and a half days for the workshop as follows:

- As an input, we use the design brief and pictures of other creative spaces.

- The procedure provides for a warmup in the morning, followed by individual brainstorming and several brainstorming sessions in connection with prompt translation into prototypes. The testing is done with employees in the cafeteria and coffee corners. At the end, the final prototype is presented to the decision makers.

- As a result, we’ve now got two to three models of a prototype, which we will either continue to improve or order to be implemented.

- Because the approach contains many elements of a design thinking cycle, the participants become familiar with it.

How might the workshop agenda for the two days look?

| Prototyping workshop, model creative space | ||

|

||

| Input | Sequence | Output |

|

|

|

| Resources | ||

Catering, tables, chairs, pin boards, flip charts, blank walls, . . . |

Timer, prototyping material, Post-its, pens. . . |

Team, facilitator, jury, . . . |

We need an environment that is familiar to us and with which we can identify and in which we feel comfortable. The designing of such an environment is essentially about four elements: the place, the people, the process, and the meaningfulness of the work. The work environment has become one of the most important instruments for a company to retain the best talents and high performers. Does anybody today want to work in an office that radiates the faded charm of bygone days and was probably squeezed down to the last square foot?

Companies like Google or IDEO are good examples of shaped work environments; Apple’s new headquarters in Cupertino, California, initiated by Steve Jobs in 2011, is very inspiring. The building was consciously planned in a natural environment, surrounded by a forest. Jobs’ vision was to create the best company building in the world. The building stands for the future and resembles a spaceship. The new headquarters was to take into account all sorts of desirable things for people.

The process and the way the work is done likewise have a great impact on the results. For one, the focus is on the type of activities we must perform; second, on the interactions of the people among one another and their influence on the course of the project. Bear in mind here that the work process itself is in a constant interaction with the environment and the people involved.

The meaningfulness of what we do as motivators is often underestimated. Companies often lack a clear strategy from which the teams could deduce whether their activities aim at something greater. Surprisingly, the majority of companies have a hard time defining the “why.” Especially for the much-cited millennial generation, meaningfulness is a key criterion for choosing an employer. There is no question that a meaningful activity boosts motivation. This applies to all of us. We will come back to the theme in Chapter 2.6.

In many cases, the management of a company is unable to cope with new, rapidly changing framework conditions (e.g., digitization). This uncertainty leads to greater aimless action in the company, but little work is done toward a specific goal or a defined market position.

In Chapter 3.6, we will discuss the question of how to deal with such uncertainties and present approaches and methods we can use, for example, to initiate and successfully implement digital transformation.