2.2 What are the benefits of interdisciplinary teams?

Peter collaborates with different teams in his projects. To be successful, he emphasizes two dimensions: The team members must have in-depth technical knowledge as well as a broad general knowledge. For Lilly’s students, it is a wonderful feeling when they have finally advanced a step with their own question and gotten out of a deadlock. It often occurs because the participants have asked others for advice. Regarding the same problem from a different perspective often helps find a way out of a dead end.

With many problem statements, there are limits to how much your own skills can contribute to the solution of the problem. The reason for this is usually a lack of knowhow and experience in a specific subject area. No later than this point, the design team must consult an expert to get ahead. Frequently, it so happens that the expert begins his or her own work way before the actual topic is discussed and poses critical questions instead of simply tying in to their area of expertise. As a consequence, the things that were developed so far assume a new quality because they are suddenly considered using a holistic approach and not from a limited perspective.

The principle of iteration is, as you will know by now, a crucial element in design thinking. Take one step back, do another lap; it helps you get closer to an ever better product, which corresponds to and meets customers’ needs. However, the most important thing is that we learn and iterate at a fast pace. This, in turn, only works when the questions are asked—and challenged—as early as possible and the things developed so far are looked at from a different perspective. The most promising way to achieve this is the exchange with potential users and on the team, which consists of different experts with in-depth and broadly based knowledge.

What characterizes an interdisciplinary team?

In very general terms, interdisciplinary means comprising several disciplines. On interdisciplinary teams, ideas are produced on a collective basis. In the end, everybody feels responsible for the overall solution. A methodological and conceptual exchange of ideas takes place on the way to the overall solution.

In comparison with multidisciplinary teams, they have the advantage in that, at the end, everybody stands behind the commonly created product or service—a factor of success that multidisciplinary teams, for example, cannot afford. On a multidisciplinary team, every member is an expert who advocates his or her specialization. The solution is often a compromise.

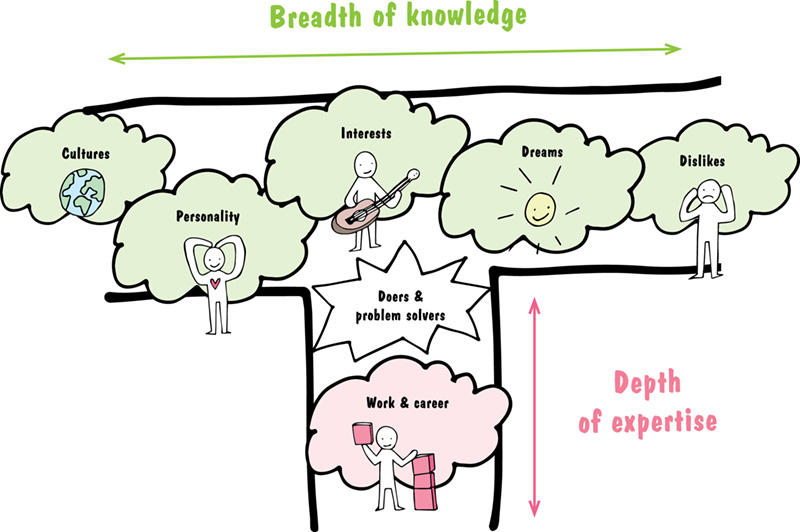

As mentioned, Peter wants to rely on the in-depth and broadly based knowledge of his teams. This idea is based on the principle of so-called T-shaped people–people who have skills and knowledge that are both deep and wide. The visual profile of skills is like a “T.” The concept was developed by Dorothy Leonard-Barton.

The vertical bar of this “T” profile stands for the respective specialist skills that someone has acquired in his training and that are required for the individual steps in the design thinking process and the implementation project. A psychologist, for example, brings along experience and methodological knowledge to the “Understand” phase.

The horizontal bar is defined by two characteristics. One is empathy: This person is able to take up somebody else’s perspective while looking past his own. The other is the ability to collaborate as well as interface expertise: T-shaped people are open; interested in other perspectives and topics; and curious about other people, environments, and disciplines. The better the understanding of the way others think and work, the faster and greater the common progress and success in the design thinking process.

Lilly still plays with the idea of founding a consultancy firm for design thinking. She would need to recruit her future colleagues against a T-shaped profile in order to cope with the professional challenges and be able to work as a team, on which all have the same social skills. It is probably easier to find people with specialist skills for the individual process steps—corresponding to an I profile—than those who have both forms of knowledge.

A good sign for the ability to collaborate, from the horizontal bar, is when people during the interview talk not only about themselves but also emphasize what they have learned from others and how valuable the collaboration was for the common project.

Quite specifically, it can help to have the potential candidates create their own T profile. The way somebody fills out the profile yields a lot of information on his way of thinking and expressing himself. At the same time, it shows how somebody interprets the requirements for collaboration and presents himself in this respect.

If you want to take the time and experience potential team members in actual practice, you can hold something like a design thinking boot camp. It can serve several purposes: For one, it is a quick and easy way for candidates to experience design thinking and its individual steps in practice and judge for themselves if they want to collaborate in this way. Second, those who assemble the team quickly get an idea of the specialist and social skills of future team members.

Interdisciplinary teams have many advantages, which, among other things, lead to a better-quality result within a shorter time. At the same time, the complexity of the collaboration increases with this approach compared to an individual way of working, without iterative agreements. The complexity can be reduced using a few simple rules, on which the entire team should agree from the outset if the collaboration is to be successful. Some of them already comply with the principles of design thinking anyway, but it has proven to be of value for the team to reflect on them consciously again.

The sooner the strengths of each individual team member can be experienced, the more interdisciplinary teams are able to benefit from the skills of the others in order to achieve the common goal. Putting teams together with people not only from various disciplines and departments, but also from different hierarchical levels, has proven to be of particular help in practice. Besides the exchange of specialist knowledge and methodological expertise, it also gives the team access to a broad knowledge and the necessary problem-solving skills. As a by-product, the new interdisciplinary approach will spread faster and transversally throughout the whole company, so this type of collaboration will be better understood on all levels.

Six simple rules for a successful interdisciplinary team:

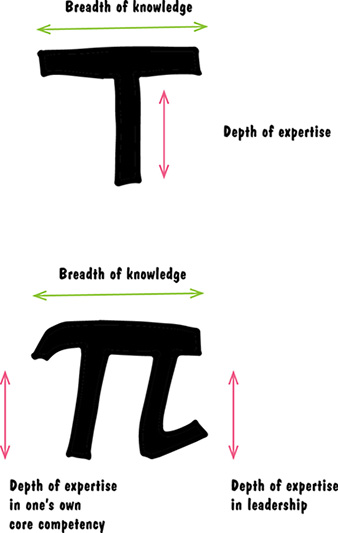

With respect to the founding of her company, Lilly is already thinking about the future. She is not satisfied having “only” T-shaped people on her team; she also thinks about how employees should develop. Her idea of the ideal company size is a team of 15 to 25 employees, in which technical skills are represented multiple times. This would allow her to process several projects at the same time. To be able to mix employees and constantly put together new teams that mutually inspire each other, the professional and human basis just described is decisive. Within the framework of a learning organization, Lilly finds it important that her employees constantly develop: from T-shaped people to Pi-shaped people.

This corresponds to the profile of an adaptive employee who develops further in addition to his specialization. Such an employee is not only able, like in the T profile, to steep himself in the discipline of his colleagues and understand it; he also has the ability to respond to challenges of everyday working life and educate himself accordingly. In this way, he can assume multiple roles, which usually are linked to one another in terms of content: for example, business analyst and UX designer or software developer and support employee. Within the company, such a profile contributes to increased flexibility in the composition of the teams, something especially relevant to smaller companies with limited resources and a quickly fluctuating order situation.

Two things are vital for a successful transformation:

- Identify gaps on the team and the development potentials of individual employees.

- Draw up a training schedule to close gaps and promote employees.

In step 1, the company management and team leaders identify gaps and potentials and discuss personal interests and associated development paths with the employees. Subsequently, Lilly should create a training schedule with her employees and the team leaders that is attuned to both corporate and personal goals and verifiable by means of defined milestones.

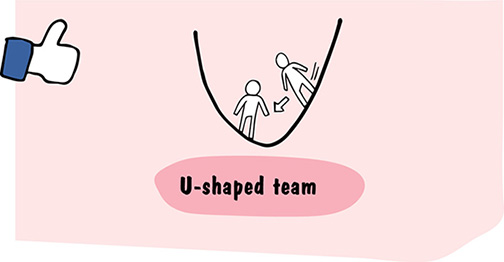

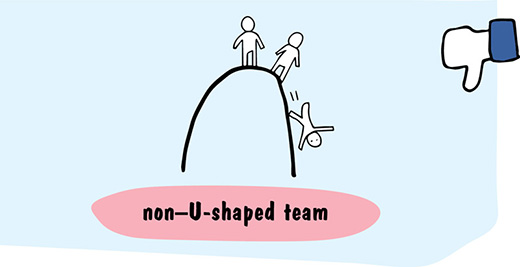

In addition to the basic professional and human skills and development schedules, one component is of particular importance to Lilly: harmonious togetherness, a team in which everybody can rely on everybody else. What is important to Lilly is that her employees like coming to work, feel accepted and safe there, and fall softly if they fall. The technical and professional expertise that is represented multiple times on the team, a learning organization, and empathetic employees constitute a good solid basis for a so-called ”U-shaped team.” This form of a team is also crucial for a high level of effectiveness because safety and security mean productivity.

The name can be inferred from the analogy of established systems, which, after a disruption, return to an equilibrium and are more stable than they were before. Systems that break at the first sign of friction are the opposite.

U-shaped teams help one another, are there for one another, even if one member has a bad hair day and is not able to deliver his usual performance; these are teams in which you can make a mistake without having to be afraid of losing your job.

Lilly’s motto: People who feel safe, secure, and comfortable, who are supported and appreciated—with all their rough edges, warts and all—are highly motivated to deliver a great performance.

The application of the design thinking mindset and the associated methods with an interdisciplinary team are key factors of success. From a business point of view, the principles of T-shaped people developing into Pi-shaped people should always be borne in mind—on the basis of a U-shaped team.

In the section on the working environment, we already discussed the key factor of success for teams of needing the conviction that their task and their goal are meaningful and useful. The idea of a “team of teams” will be examined in Chapter 3.4, which highlights the successful implementation of market opportunities. We would like to note at this point, though, that the personal relationships of and networking between individual people beyond the teams must be seen as decisive in the success of teams.

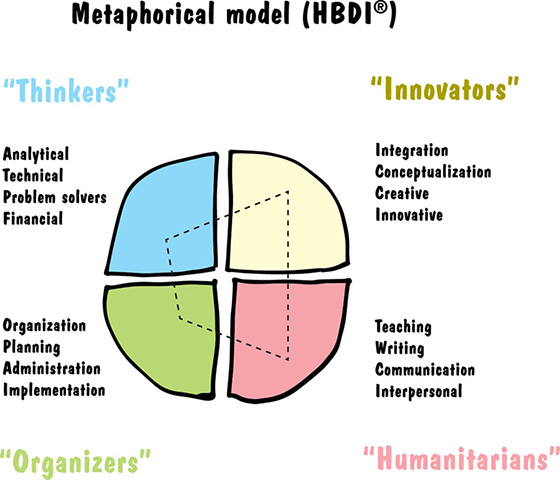

The ideal is that we can equip our teams with people who have different preferences in their thinking; this is how we get high-performance teams in the end. The myth that the left hemisphere of the brain is responsible for analytical thinking and the right hemisphere for holistic thinking is widespread. But because our brain is anything but well organized, such a simple division into two halves is quite wrong. Tendencies can indeed be identified. Our understanding of numbers, for instance, or our ability to think spatially and recognize faces, is more localized in the right half of the brain. Other capabilities, such as recognizing details or capturing small time intervals, are localized more in the left half of the brain.

There are models that try to capture the brain as a whole and determine preferences in thinking. One example of this is the Whole Brain® model (HBDI®) that breaks down our brain into four physiological brain structures. The model consists not only of the left and right mode but also involves the cerebral and limbic mode. This view allows us to differentiate more styles of thinking such as cognitive and intellectual, which are ascribed to the cerebral hemispheres, and structured and emotional, which describe the limbic preferences. In our experience, it can be quite valuable to swap the thinking preferences on the team; individual tasks are assigned to the respective people in the relevant phases during the design process. Ultimately, better solutions are achieved this way. It also helps us when communicating ideas and concepts to decision makers and telling the story of new products and services we want to launch on the market.

If we have little time and want to learn something quickly about the participants in a workshop, we still use the model of the two halves of the brain. It helps to classify the participants roughly into the categories of “analytical/systematic” versus “intuitive/iterative.” We have learned that the combination of the various thinking models and thinking preferences is essential for a successful design thinking project.

Marc and his team are already quite well set up for their start-up: Innovators such as Marc, women with a business sense like Beatrice, makers and shakers such as Vadim, and team members like Stephan and Alex, who actively control the business development.

In our experience, teams are most effective when they have one team member each with a strong manifestation of one of the quadrants in the metaphorical model.

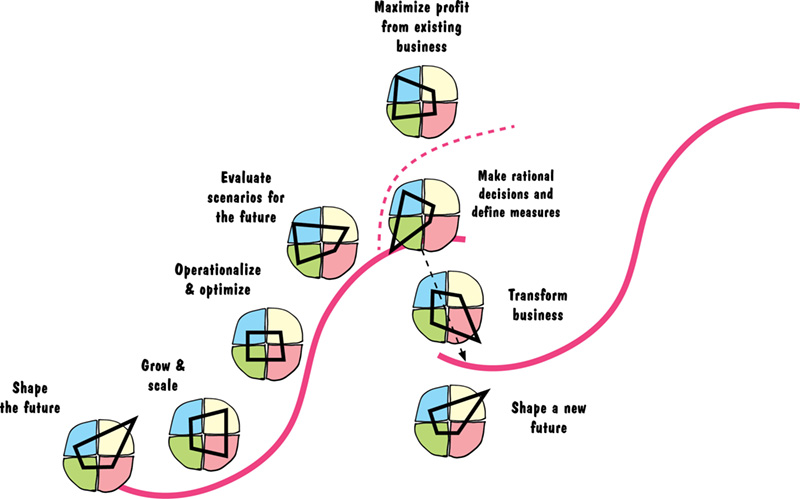

Marc would like to shape the future. He has a great vision for the health care system of the future, in which patients decide autonomously which information goes into their electronic patient record. In a first step, he focuses on a few functions of his idea that he will implement on the blockchain and with the relevant actors in the ecosystem. Marc’s HBDI® profile is characterized by a focus on the yellow and blue quadrants.

For the set-up and growth phase of their start-up, other skills that Marc and his team already possess are necessary alongside Marc’s great vision and his programming skills. By way of example, we can place the respective HBDI® profiles on an S curve and put Marc’s team members across the growth phase of a company.

Rational decisions must be made and measures defined for the next scaling step and for the transformation of the company from a start-up into a mid-sized enterprise. Above all, team members with strong organizational (“green”) and interpersonal (“red”) characteristics are necessary for this. Both are currently underrepresented on Marc’s start-up team. When expanding his team, Marc should therefore make sure that this missing expertise and these capabilities are included on the team.

Using the teams of teams concept, the respective skills in larger organizations can be utilized for all design challenges. This will pay off once Marc’s company grows and individual squads work on different functionalities for patients and for involving other actors in the ecosystem.

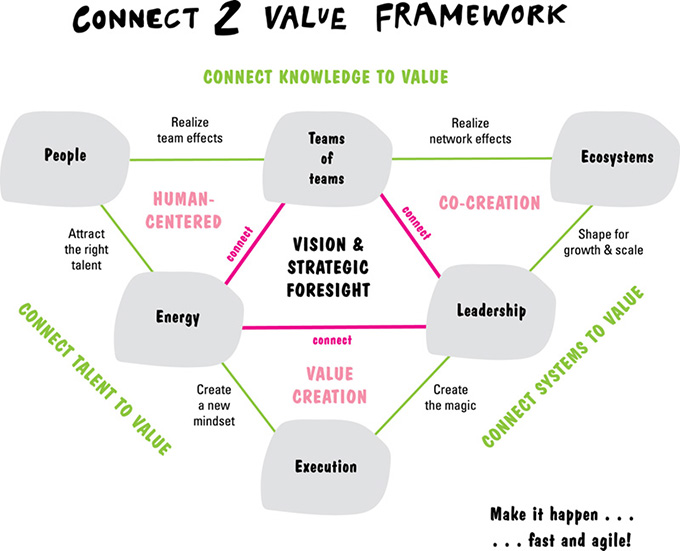

Marc works with the six principles from the “Connect 2 Value” framework (Lewrick & Link) in order to develop his start-up successfully.

The “Connect 2 Value” framework is based on three levels:

- Connect knowledge to value

- Connect talent to value

- Connect systems to value

It combines the design thinking mindset with the core aspects of a human-centered approach, co-creation, and value creation as well as with strategic foresight for the definition of a clear vision for the enterprise.

It also combines the talents of people in the company so their knowledge and skills can be unfolded to their full potential through the connections in the business ecosystem, and ensures that top talents are deployed in those places where they can create the greatest value for the company. Relevant internal and external needs are satisfied by the human-centered culture and its positive energy. Internal teams and expanded teams from the business ecosystem create value together.

- People: Attract the right talents

Marc does not just consider the skills, the T profile, and the HBDI® model but also invites potential candidates directly to his workshops to find out whether they generate a positive energy and mood on the team and live the design thinking mindset.

- Realize team and network effects

The composition of the teams and a goal-oriented collaboration, internally and with external partners such as in the business ecosystem, are key factors of success. Marc sees the human beings behind the companies in the business ecosystem as team members, too.

- Shape for growth & scale

From the outset, Marc co-designs the business ecosystem. He creates a win-win situation for all actors. He uses technologies and platforms for scaling, which also make the realization of data-driven innovations and business models possible.

- Create the magic

For Marc, leadership means to bring the magic to the team and make possible the impossible for them. It includes the creation and communication of a business vision, which helps to encourage the teams to fulfill their mission and act in an entrepreneurial way.

- Create a new mindset

Marc is aware that positive energy is the elixir and driver of outstanding achievements and motivation. An open feedback culture, for instance, allows the top talents to contribute their skills optimally. Ideas and concepts are implemented quickly, and failure is part of a positive learning effect.

- Make it happen

With the support of the top talents, the business ecosystem, the right mindset, and the right processes, Marc implements the concepts—fast and agile. In so doing, Marc assigns the top talents and resources to those activities that generate the greatest value. He consciously uses external skills and platforms of actors in the ecosystem for the realization.