2.4 How to design a good story

Good stories have accompanied humanity for thousands of years. In olden times, the profession of storyteller used to exist. Today, books and new digital media have replaced this profession. But we still like good stories. Pretty late it was discovered—and accordingly used—that products and objects can tell great stories as well. Architects such as Gaetano Pesce, one of the icons of Pop Art design, once remarked that we are separated from objects as long as consuming them is the only primary reason for their existence. Why do we take Pesce as an example? Peter has told us about his enthusiastic admiration of Pesce. He was particularly taken with the “La Mamma” chair, UP 5, from 1960. We’ll leave the question open whether the chair has any resemblance to Priya at this point; it’s up to your imagination. We will discuss later why imagination is important and what all this has to do with storytelling. First, some information on the UP 5 chair: It has the shape of a woman—hence the name “La Mamma”—and was inspired by prehistoric fertility goddesses. To implement his idea, Pesce used an innovative technology that allows the creation of large foam-molded parts without a load-bearing inner structure. Thanks to a vacuum chamber, the piece of furniture could be reduced to 10% of its volume and thus shrink-wrapped in air-tight film. This made it easy for the buyer to get the piece of furniture home. Only once the film was removed did “La Mamma” unfold to its original and final size and shape.

Until the 1960s, design was defined by the actual function. Many designers perceived the relationship between the consumer and their products primarily through their actual use. It was only in the 1970s that some designers challenged this paradigm. They added “nonfunctional features” and artistic elements and ornaments to their objects. This showed that the relationship to an object can consist of more than merely its primary functionality. Since then, functionality often has not taken center stage. A more holistic relationship with the object emerged, with a deeper meaning for the consumer. Without this deeper meaning, a product is not perfected in the eyes of the consumer. This means that the consumers became the actual designers. They create the meaning of an object through the intimate relationship they establish with it. Lilly has observed this behavior often in her younger students, who have such a close relationship with their smartphones that they give them pet names.

A headline in Forbes magazine claimed that good storytelling can heighten customer acquisition by up to 400%. Now we all see the $ sign flicker in front of our eyes, which ought to make us sit up and take notice. With all services and products, the ultimate art is to maintain the desire for them, which is based mostly on the relationship between the object and the consumers. Desire is exactly the condition that the object or product does not have, though. Instead, it is the presumed relationship with the object that satisfies desire. With his dream car, an American electric vehicle, Peter is one of these modern consumers who “cultivate” their desires. Any product with hitherto unknown features has the potential to fill us with enthusiasm beyond the limits of reality. We can compare this state with daydreaming or the merging of feelings of happiness from fantasy and reality. In general, we are all confronted with a dilemma that becomes manifest in the desire to own the object and the fact we don’t own it.

It seems we find the perfect experience more with new products than with goods we already own, which have lost the capacity to embody the perfect experience. With the actual use of a product, we have the opportunity to experience our fantasies and dreams, which we have built up beforehand and that revolve around the product. This doesn’t mean that a product will become interchangeable as soon as we have bought and used it. Consumers have the power to turn their personal objects into something special.

Stories are an excellent means of describing the various relationships between consumers and products. For some products, especially when it comes to fashion, a good story is of greater value than the function or the quality of the clothes. With the help of stories, consumers can identify with the clothes they bought and display their fashion style to the outside world. Storytelling has the potential to speak to the audience like this: “Hey, it’s really only about you!”

In general, we distinguish three types of stories, which are important in the perception of products:

- Commercial stories from manufacturers such as Coca-Cola, who use them with great skill and cleverness in their marketing. We all know the famous taglines of Coca-Cola such as “Release the brrr inside you” or the Coca-Cola Christmas stories, which for generations have become an integral part of the run-up to Christmas. Although Coca-Cola today has become more personal—through promotions such as “Share your family photo,” “Your own name on the bottle,” or the current series of “Drinking a Coke with your friends”—we have stored these images deep in our unconscious.

- Lifestyle stories from and about users. These stories are often associated with emotional goods such as cars, motorcycles, watches, and other luxury items. Consumers buy these goods to pursue a specific lifestyle. The Chevrolet commercials “Maddie” and “Romance” are good examples of this because they tell profound and unforgettable stories. The stories build a close relationship with the consumer far beyond the actual product. Often, the stories are supported by so-called fan clubs.

- Stories with the character of a specific memory. These individual stories are based on the personal memories of things past and vary from individual to individual.

A good story or a story that is told perfectly always follows a typical narrative. In so doing, an arc of suspense is created, so listeners remain attentive.

This arc of suspense is essential and is built up continuously from the first moment—right up to the final punch line.

A good story that works usually includes five elements:

- an emotionally significant initial situation;

- a (likable) main character;

- conflicts and hindrances, which the main character must overcome;

- a recognizable development and change (“before and after” effect); and

- a climax, including the conclusion or the moral of the story.

Good stories induce emotions in the viewer and convey a message. To be able to tell a good story, we must know our target group quite well. Again, it is of great importance to have built up empathy beforehand. The topic of empathy has already been extensively described, so in this section we will put empathic design in the context of other design approaches.

Many approaches have contributed to the development of empathic design or are based on similar thoughts.

Empathic design is the development of products and services that are based on unspoken customer needs. New tools have been added over the last few years that allow companies to understand the mood of the customer, making it possible to experience a situation from the customer’s point of view. This experience frequently yields important product information, which cannot be tapped by means of normal market analyses and well-known empathy tools.

In many companies, such approaches have become an integral part of product development. The use of so-called third-age suits is a good example.They allow designers and product managers to experience with their own body the limited physical capabilities of seniors. There are also methods that require less technology and focus on specific senses. The goal of geriatric sensitivity training is to make certain physical states palpable. Glasses that simulate the clouding of the cornea or age-related macular degeneration can help users experience how these impairments affect everyday life. Alongside the glasses, there are gloves that simulate limited sensitivity and headphones that replicate a hearing impairment. The experiences are conducive for the development of products, services, and processes.

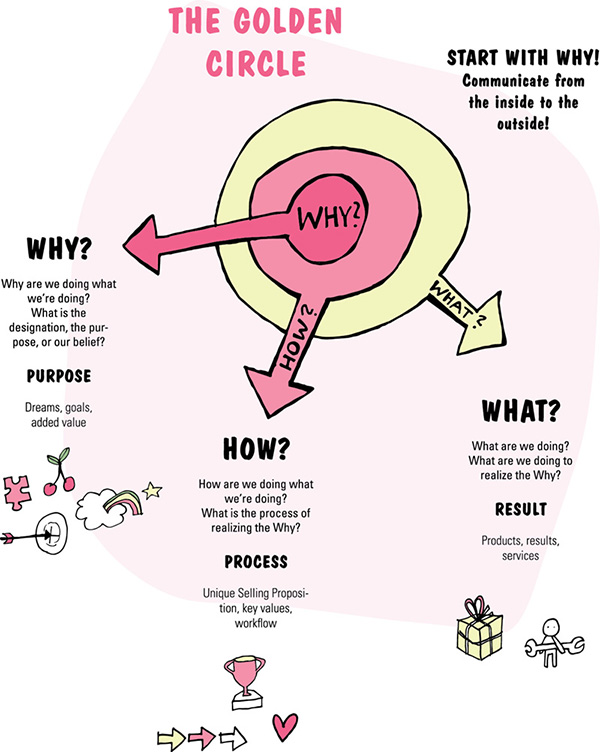

For all of us, it is easier to become motivated when we can imagine the purpose of our actions. This way, the belief that we can achieve a set goal is strengthened. For this reason, it is always advisable to start with the Why. In the model of the Golden Circle, the Why is in the center. The limbic system (Why) is located in the center of the brain and is guided by emotions and images. We’re dealing with behavior and trust, emotions, and decisions here.

Successful companies keep the Why on center stage with a clear vision. In such companies, employees know why they get up in the morning and go to work. Spotify, for example, has the great mission of bringing music to the world.

The How describes how the work is done and which particulars it involves result from the Why. Apple is another much-cited example in this respect.

The logically thinking brain (What) is located on the outside in the model of the Golden Circle. It encompasses rationality, logic, and language. The How connects the two elements and explains the process of how something is done.

The inventor of the Golden Circle, Simon Sinek, expresses it this way: People don’t buy what we produce—they buy why we produce something. This is why we should always start with the Why. The same model applies to internal communication (e.g., to digital transformation). Successful business leaders communicate from the inside to the outside in the model of the Golden Circle. Employees know why they do something, how they do it, and what they do.

A tried-and-tested tool for the generation of emotional stories is the Minsky suitcase.

Do we know where our suitcase is at the moment?

Most of us are likely not thinking about our suitcase just now. It is somewhere in the basement or stored in a closet. Nothing unusual here. Once life has returned to the daily routine after vacation, the memories of fine dining on the French Riviera or the white sand beaches in the Maldives quickly start to fade away. The last memory of the vacation consists of a few grains of sand hidden in the inner pockets of the suitcase. For a certain period of time, our suitcase was a synonym for a different lifestyle, a better life, life as it ought to be: with pleasure, relaxation, an uncomplicated and free schedule.

Maybe we never actually thought about it, but the items in a suitcase have basically four different types of use:

- things of everyday life (toothbrush, socks, change of clothes),

- things that are very important to us and do not take much space (a photograph, a lucky charm, or a diary),

- things we want to impress people with (jewelry, a fashionable scarf, cool sunglasses), and

- some free space for things we want to purchase on our trip.

A packed suitcase is the compressed version of our personality:

It is orderly, chaotic, an imitation, an original, it bears traces of past adventures, and so on. When we travel, each of us has exactly the suitcase that fits us best and is thus a mirror image of our life.

To tell emotional stories, a suitcase can be an inspiring starting point. We find old suitcases in the attic or buy a new one at the flea market. In a second step, we build up a relationship with the suitcase and its contents. Why was the suitcase forgotten under the roof? What could its story be? We take some time and write a small fictional story about the object and its possible relationship with its former owner.

Let’s assume there’s an old, heavy winter coat in the suitcase, and our design challenge is to create a new soap. No restrictions are imposed on our design team in terms of the shape, smell, color—but it’s not only the soap that is to be designed. The packaging and the marketing concept must also be created. The following story might have emerged from the inspiring framework of the old winter coat:

Two examples of a possible product are the “Savon 1890,” a very simple, old-fashioned, handcrafted soap in plain packaging, and “Soap Crystals,” which are based on the experience with an old walking stick.

We all know the problem of how the respondents in a direct user survey describe their own behavior as an ideal type but do not show their true self. We ask them about their goals and desires, but the reply only consists of the most obvious insights. One way to reach users on a more emotional level is to offer stories of their dreams, which give us the opportunity to learn things that go deeper and reveal their true needs and desires.

A project with the name “wearable dreams” is a good example of how such stories about dreams can provide an inspiring framework for a design thinking project. In this project, the interviewees were initially asked to imagine that their favorite piece of clothing was a person. Then they were asked to describe the personality of this person:

- What is the name of the favorite piece of clothing?

- How old is it, and what does it do for a living?

- Is it pretty shy or rather extroverted?

- Where was it born, and what is its marital status?

This way of talking about a product helped the interviewee to think about his favorite item of clothing and thus transported the object into a social and emotional context. The remaining interview built on these dreams. The respondents were asked to imagine the person depicted by the item of clothing in a difficult situation. Fortunately, the person had super powers that got him out of the situation.

Initially, the respondent was asked to describe a situation that he or she did not want to get into. In addition, the person was requested to choose a specific role and take it on. The questions were, for instance:

- How do the surroundings look?

- Are there any other people?

- What items are lying about?

In the ideal case, the respondents wrote down a little story they made up about how the person got out of the difficult situation. They were asked not to reflect too critically on what is possible or impossible in reality. Ideally, the whole thing was pepped up with drawings. The length, content, and depth of the story were irrelevant.

The design process builds on this information. The idea behind it is that objects must satisfy our emotional needs, for one. Also, our rational stories are the best way to transport these needs.

Design trends such as a popular style, and hip combinations or colors are not the real trend. These attributes are only the tip of the iceberg. To identify the true trends, you have to dig deeper. This is the only way to reveal the artifacts. Changed behaviors, beliefs, and social forces make up a trend.

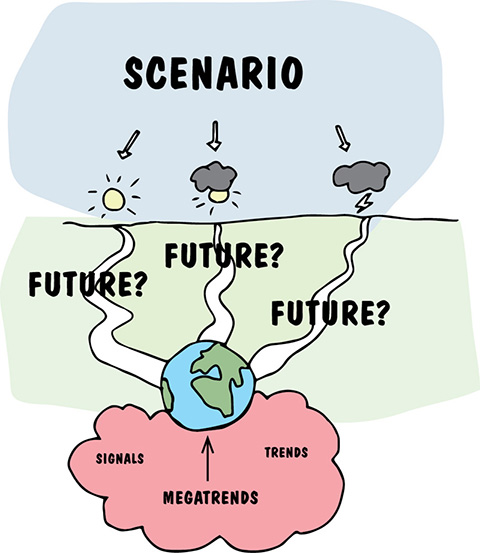

We know scenarios as descriptions of alternative possibilities, based on which decisions for tomorrow are made today. They aren’t forecasts or strategies but are more like hypotheses about various maps of the future. They are described in such a way that we are able to identify the risks and opportunities in terms of certain strategic realities. If we want to use the scenarios as an effective planning tool, we should design them in the form of captivating and, at the same time, convincing stories. These stories describe, for instance, a range of alternative future scenarios that will lead the organization to success. Well-thought-out and credible descriptions help the decision makers immerse themselves in the scenarios and perhaps even acquire a new understanding of how their organization can master possible changes on the basis of this experience. The more decision makers we introduce to the scenarios, the better they recognize their importance. Moreover, scenarios with easily comprehensible contents can be taken quickly into the organization as a whole. These messages stick easier in the memory of employees and managers at all levels.

The use of future scenarios for visionary projects differs from the daily work in project or product management. The scenarios constitute an inspiring guide into a possible future. Visionary projects not only serve to inspire the entire organization and challenge existing technologies; they also help to galvanize individual employees. Thus the future scenarios seem to have a great influence on the organization; however, they are more difficult to orchestrate because they deal with the unknown. Organizations are often unable to initiate the transformation and fall right back into their daily routines—not least because the future changes had not been sufficiently prepared for. To avoid this relapse, companies like Siemens publish “Pictures of the Futures” at regular intervals.

Pictures of the Future (Siemens) link realistic current trends with distant future scenarios to align and direct business activities. For one, the future scenarios created can be used well to formulate or redefine the starting question in design thinking, and can give further momentum to the process of creative problem solving on the team.

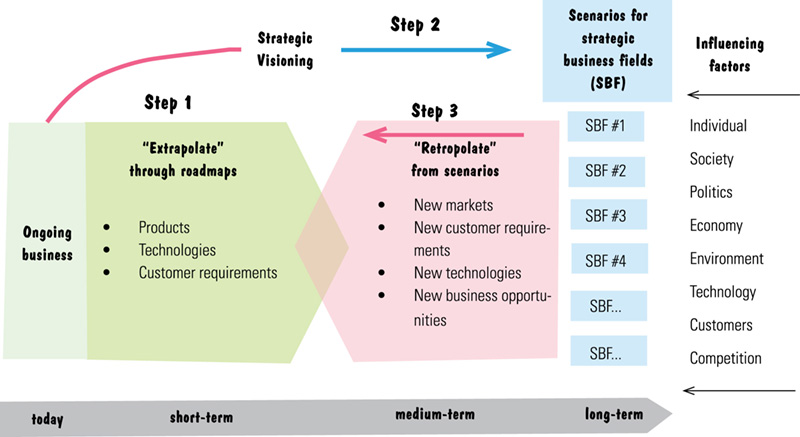

Step 1: We extrapolate from the world of today

We start with the daily business of our company and look at the trends, from which we extrapolate how the near future of our company might look. Data and information from different sources, such as industry reports and interviews with experts, are analyzed. The fastest way to reach our goal is to fall back upon the known trends in an industry, like internal trend reports and market analyses, which are freely available on the Internet. For example, we take the general Gartner Technology Hype Cycle as a starting point. Our best course is first to compile a provisional list of trends; discuss them briefly on the team; and note the estimated importance, strength of impact, and the degree of maturity of the relevant industry.

Step 2: We apply strategic visioning

We detach ourselves completely from our own business focus and our own professional blindness and design various distant future scenarios with a true outside-in perspective, independent of our own company (in the example, four scenarios have turned out to be ideal). Because we are dealing with distant scenarios, elaborate studies are usually carried out with the inclusion of worldwide research. Luckily, Siemens has already done this work for many industries with their Pictures of the Future and has made the results available free of charge (among others, from the sectors of energy, digitization, industry, automation, mobility, health, finance, etc.). We choose a positive, constructive, and profitable scenario and ask ourselves: “How might our company make a maximum contribution to this scenario? What would we have to do and offer?” We stay in the future in our thoughts and do not allow the processes and structures of our company today to influence us.

Step 3: We “retropolate” from the world of tomorrow

We carry out a retropolation from the scenarios. The point here is to draw conclusions for the present from the “known” facts of the future scenario. We juxtapose the results from step 1 with those of step 2, combine them, and infer from that what it means, in very specific terms, for the alignment and direction of our company today. In which directions should we innovate and do research? What skills must be developed? What personnel should be hired? And how should processes be redesigned so we are prepared for coming challenges and opportunities?

Well-thought-out digital storytelling is becoming more and more important. After all, we use different digital tools every day and consume a correspondingly high amount of digital words. Digital storytelling gives us the opportunity to represent our company perspectives in more detail and use emotions in order to get more attention.

Storytelling consists of two words: “story” and “telling”—content and performance. We know traditional storytelling with a narrator, who performs in front of his audience. Nonverbal reactions help the narrator to assess how well the listeners are following him, so he can react spontaneously. The digital world has none of these nonverbal reactions. We must use other tools to establish empathy with a digital potential audience.

There is a broad range of media we can use, from multimedia films to audio broadcasts all the way to webinars. To select the right content and media, it is important to develop a deep understanding of the target group. We recommend creating so-called buyer personas and getting information from potential customers:

- Why buy from us?

- How do customers find us?

- What questions are we asked during the sales process?

- What motivated the customers to search for a solution?

Because all of us are addressed on multiple levels, emotional and intellectual elements associated with our brand are equally important. It helps in this context to flesh out the storytelling with data and facts. We also have the option of encouraging our users to generate content.

Lego provides an intriguing example of a digital story:

Problem: Lend a new profile to an old children’s toy

Campaign: 90-minute “Lego film”

Agency: Warner Bros., Hollywood, CA

Solution: A good movie for young and old with the message that we are imaginative builders at any age.