3.4 How to bring it home

Design thinking underwent various eras in the past. There was “synthesis” in the 1970s, followed by “real-world problems,” all the way to business ecosystem design. Across all eras, we were faced with the challenge of successfully implementing the solutions in our organizations.

We know from experience that various stakeholders in the company want to have their say. The process toward the solution is often scrutinized. The colleagues from the Legal department already raised objections to our very first prototype; the experts from Technology are generally not open to solutions they haven’t developed themselves (“Not invented here” syndrome); and the hip ones from Marketing are bound by strict specifications for the branding of the new solution.

In addition, there’s the opinion of Management, the concerns of the Product Management Board, and all the other countless committees who question our ideas and block implementation. In most large enterprises, we will encounter resistance of a similar kind, not least because a rather traditional innovation and organization approach dominates most organizations. It is characterized by minimization of errors and maximization of productivity, the desire for reproducible processes, elimination of uncertainty and variation, and the need to increase efficiency with best practices and standard procedures.

Design thinking as such offers a great basis for initiating transformation and innovating in an agile way. We consciously bank on interdisciplinary teams and radical collaboration, promote an experimental process through iterations, and thus maximize the learning success.

Nonetheless, many of our ideas fall by the wayside and never get to market. As mentioned, one of the core problems here is that the stakeholders in the company are not part of the creative nucleus and often act within the structures and mindset of yesteryear. The style in which leadership is lived is frequently resistant to change in implementation projects. Even at a late stage—just before the market launch—willingness to change is greatly in demand. Just prior to the launch, we might realize that others were faster at bringing the solution to market. This is the point at which we ought to ask ourselves a number of important questions, because the answers to them will ultimately decide if our idea is on top or a flop:

- How can we nonetheless achieve a market success with other approaches?

- Have we thought through all types of business models?

- What value proposition creates a “market buzz” on the part of the customer?

- Are there any possibilities of partnership projects in the ecosystem so that our solution gets scaled?

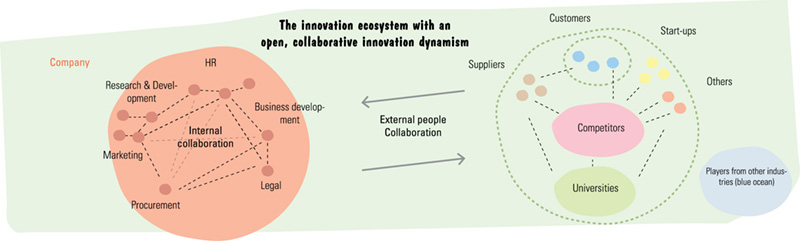

As described in earlier chapters, collaboration with partners is becoming more and more vital for success in the digitized world. Many components can be provided by companies in the business ecosystem, in particular when it comes to technologies that we don’t master ourselves. Collaboration can be stimulating for the development of the actual idea. The advantages are obvious: We boost speed and efficiency, participate in new trends and technologies, and reduce development costs. As a company, however, we need the ability to deal with open innovation models for this, especially in the form of collaboration, and explorative/exploitative skills. With regard to the latter, we are swiftly confronted with the problem of intellectual property (IP). But what seems to be even more important today are aspects such as who owns the data of digital solutions and the question of usability.

In the collaboration of traditional businesses with start-ups, two cultures clash, each of which follows different rules and has different hierarchies. Companies that are open to a so-called intrapreneur approach have the opportunity to develop a corporate culture in which higher risks are taken. Such approaches benefit from the fact that autonomous teams develop their ideas independently and with an entrepreneurial spirit, scale existing innovations, or establish themselves on the market as a spin-off. This approach is antithetical to the idea of central decision making etched in the DNA of traditional companies; in addition, it holds the risk that the skills provided and limited resources will not be able to scale the idea successfully on the market.

For Lilly, her work at the university was usually over once the participants had presented their results. The implementation of the solution was not a major issue for her. Yet the feedback from industry partners and participants on the implementation made her think. Most celebrated opportunities do not find their way to market maturity.

In the case of rather simple market opportunities, the approach discussed before, namely to implement the idea with a start-up, is probably the simplest. You equip the teams with financial resources for one year, support them with coaching, and try to develop the opportunity to market maturity during this time. For one, this minimizes the risk; you also avoid all those hurdles that are simply written in the DNA of traditional enterprises. Such implementation variants have unfortunately been chosen only rarely up to now. This is because, among other things, it requires the willingness of the team to carry forward the idea in a venture for a while.

But Lilly also knows very well that implementation will be one of the most important factors of success in the future. From a study jointly conducted by HPI and Stanford in 2015, Lilly knows that design thinking brings forth many positive aspects in the field of work culture and collaboration. What is conspicuous, though, is that the top 10 effects of design thinking do not include an increased number of innovative services and products that were launched on the market. In our opinion, this is because implementation is not supplemented as the last and crucial phase in the process. As a mindset, design thinking must be established in the company holistically for it to be successfully implemented. Unfortunately, the reality is that the majority of responding organizations (72%) use design thinking in a more traditional way, namely in isolated areas of the “creative folks” in the enterprise—a fact that Jonny unfortunately observes at his employer as well. So we should not be too surprised that ideas are nipped in the bud of implementation.

We asked 200 people...

Create-ups are young enterprises that act as research laboratories. Behind these experimental labs, there is usually a strong entrepreneurial personality such as Marc and his co-founders. The founders often come from elite universities and bring in-depth knowledge from their studies as well as the capability of programming. Their intention is mainly to design new business models. They live a culture that is characterized by:

- a clear vision,

- a long-term strategy,

- a strong personal commitment on the part of the founder, and

- a high level of risk tolerance.

A typical approach for a create-up is to turn existing business models on their head and thus rock the market. They create a value proposition, for instance, that offers added value at better price/performance conditions or disrupts an existing business ecosystem. The employees in a create-up are passionate about the vision of the enterprise. Instead of power games, hierarchies, and rigid structures, the prevailing culture is one that aims at solving problems. Paired with a positive mindset, they are focused on realizing market opportunities. In so doing, they make intense use of the network that was already built up and cultivated at the elite universities. See Chapter 2.2, where we described the Connect 2 Value framework.

Established companies can learn a great deal from the create-up mindset. It starts with a clear vision, continues with a network-oriented way of thinking, and is expressed in the fact that all actors are involved in the problem solution as well as in agile and flat organizational structures.

Since we are often far removed from the create-up mindset in large organizations, it is all the more important to involve the relevant actors outside the company as well as the stakeholders within the company actively in the problem-solving process. The motto is: Turn the parties affected into participants. If we get the relevant stakeholders on board in the initial phases of the design process, they will understand much better why a problem statement has changed, which needs potential customers have, and what functions are important to a user. As soon as this understanding is given, all stakeholders will usually help proactively to bring the solution to the market. We will still sense resistance, but it will be far less than it would be were the stakeholders involved only late in the process. We have found the lean canvas approach to be a good way to do this (see Chapter 3.2). Within the company, Marketing can be included in the development of customer profiles, company strategists are closely involved in working out the financial aspects of the business model, and product managers see their responsibility in formulating an excellent value proposition. Thus all participants can identify more strongly with the development process when the solution is implemented later.

Just before the end of the design thinking cycle, it can be useful to take time again to draw up an implementation strategy. And it is even better to expend some thought on it a lot earlier. Especially in traditionally managed companies, a stakeholder map is very helpful for overcoming the many hurdles in such organizations in the best possible way. A stakeholder map helps to identify the most important actors and their relationships with one another. They are our internal customers to whom we need to sell the project. The key questions we have to ask ourselves:

- What are the current challenges from the CFO’s point of view?

- How can the CMO best distinguish himself on account of our initiative?

- What does the product management board get from favoring our idea?

- How does the idea fit the grand vision of the CEO?

- How does the idea match the corporate strategy?

- Who is blocking the idea, and for what reasons?

The procedure for creating a real stakeholder map is simple. We take a good two dozen game pieces. Pieces that already have a certain character work very well from our experience. The pieces of Lego “Fabuland” are ideal. Then we need a large table that we cover with a sheet of paper. We put out Post-its and pens, a couple of ribbons, Lego bricks, and strings. The latter are used to create and visualize connections between the stakeholders. The discussion should be very open. In the end, the required measures are defined in order to approach the individual stakeholders in a targeted way.

Every large enterprise dreams of the flat and agile organizational structures of a create-up that allow for the quick piloting and implementing of market opportunities. Transforming an entire organization is a longer task, so a step-by-step approach is advisable.

Based on our observations, we recommend starting small and banking on a gradual transition. Ideally, we begin with a team that tries out agile working and experiments with it (first level of maturity). The focus is on learning how to work agilely. In a second step, we extend this approach to a second team that has characteristics similar to the first. These teams develop, for example, new functionalities for existing products in relatively short cycles, ultimately making customers happier with their ideas; or they experiment with a new business model for an existing solution. In a third step, you start to scale the agility to the entire organization. Multiple teams autonomously develop a complete business model, a product, or a service. A clear and unambiguous strategy helps the teams orient themselves and align their activities to corporate goals. It is important that these teams establish collaboration beyond the organizational units and that middle management is willing to cede responsibility. Agile program management constitutes the basis for a lean governance of projects. In a fourth step, we can replicate the approach further into the organization with the result of transforming the existing organization into an agile organization. The best indicator for the hoped-for goal is when the agile organization innovates from inside out. In the last step, the teams act autonomously, launch new initiatives within the set mission, and implement them “on the fly” (i.e., in short cycles) on the market.

This collaboration of various teams in a multi-program organization is also referred to as “teams of teams.” “Guilds” or “tribes” are other terms frequently used in the context of such organizations.

The work in squads is most similar to that in create-ups. One company that falls into this category is Spotify, whose management consistently relies on tribes, squads, chapters, and guilds. Like most create-ups, Spotify has a powerful vision (“Having music moments everywhere”) that enables the individual tribes and squads to align their activities accordingly. Especially in technology-driven companies, a higher level of employee excellence can be achieved this way in a short time.

At Spotify, employees work in tribes. A tribe has up to 100 employees who are in charge of a shared portfolio of products or customer segments and are organized as simply as possible according to their dependencies. So-called squads form within the individual tribes that take care of one problem statement. Squads act autonomously and organize themselves. Experts from various disciplines are part of the squad and perform various tasks. Every squad has a clear mission; at Spotify, this can refer to the improvement of the payment or search functions, or of features such as Radio. The squads establish their own story and are responsible for the market launch. The mission is part of the clearly defined vision. The individual chapters ensure exchange on the technical level. Communities with the respective skills form, and are usually overseen by a line manager.

Guilds emerge on the basis of common interests. Interest groups form around a technology or market issue, for example, and then act transversally across the tribes. A guild might deal with blockchain technology and discuss its use in the music world of tomorrow.

The organization is a network with flat hierarchies. The squads work directly with one another, and boundaries between them are fluid. In such structures, we tend to collaborate radically in order to solve a problem; for instance, we meet ad hoc and dissolve the collaboration in the same way. This way, networked organizations emerge. For such approaches, it is advisable to bid farewell to traditional role descriptions and hierarchy levels.

Character of autonomous squads:

- You feel like you are in a “mini start-up”

- Self-organization

- Cross-functional

- Five to seven people

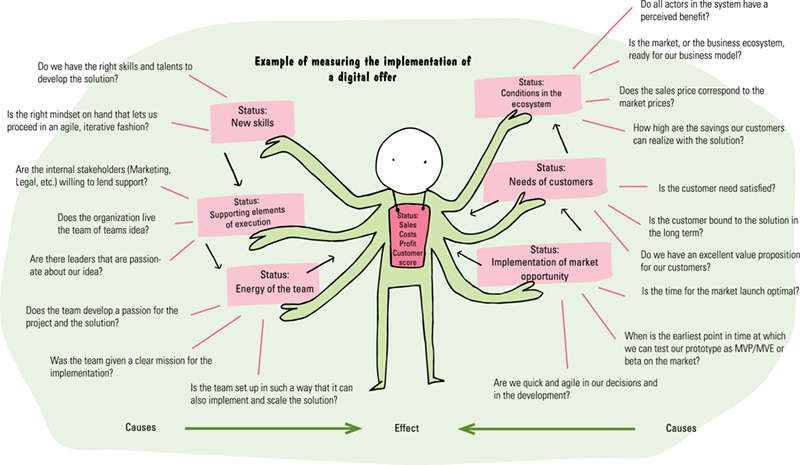

When implementing market opportunities in large organizations, we cannot avoid measurability. The dimensions of traditional balanced scorecard approaches and well-known key performance indicators are not expedient and should be replaced with new questions. In particular, if the company is in a transformation phase, they must be reconsidered and/or discarded. We recommend including the key elements of a future-oriented organization in the cause-and-effect chain. The ability to think in ecosystems and the passion of teams for the execution of the mission can be crucial elements of management.

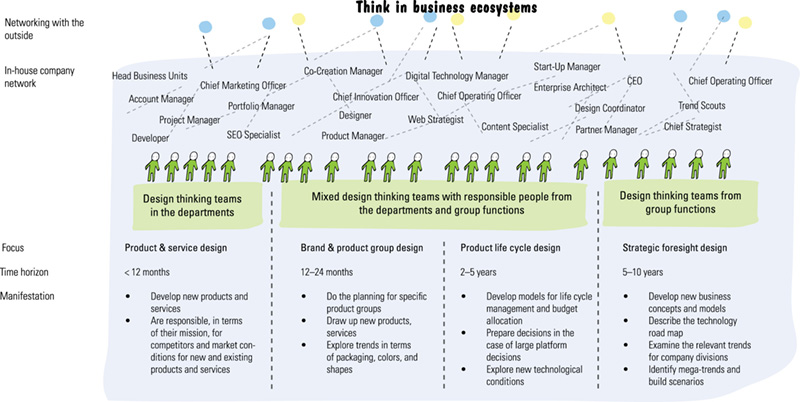

Innovation projects and problem-solving projects are used in different areas of the company. This obviously means that the time horizon and the definition of the future are also different for the individual design teams. In agile companies that are heavily based on technology, the time horizon for new services and products is usually no longer than one year. In the area of product groups, the cycles last between 12 and 24 months, depending on the industry focus. For weighty decisions regarding platforms with large investments, the standard is a time horizon of up to five years, not least due to the payback period. Strategic foresight as a design element has a perspective of five to 10 years. In addition to the desired market role, the question as to which business models will bring the revenue in the future is reflected upon. Furthermore, assessments are made as to how mega-trends affect the company and its portfolio. We have found that the continuous exchange of ideas transversally between the teams is a factor of success if we ultimately want to be innovative in a targeted way—always being aware, of course, of the time period the design team has in mind. In the terminology of a modern organization, the chapters make such a transversal exchange possible. In addition, the respective departments and business units, or squads and tribes, need the planning insights of an overriding strategy, so they can put their mission in the right context. Networking outwardly is a crucial factor of success.