At military aviation’s very beginning, the US Navy command structure saw naval aviation as something of an experiment. Early aircraft were frail and able to fly only in perfect weather conditions. Navy officials hoped that at best aircraft would provide long-range scouting services to locate an enemy, and observation for battleship gunnery once the enemy had been located. Few officers in the US Navy were able to foresee that in less than 25 years the aircraft would become the most decisive tactical weapon in the world.

Admiral William Moffett, appointed Chief of Naval Aviation in 1921 (in the same year that General William “Billy” Mitchell was appointed to head the Army Air Service), saw in aircraft both strategic and tactical potential. World War I had seen the use of the first aircraft carrier and the beginning of strategic bombing; military leaders like Moffett were planning how best to harness the military potential of the aircraft.

Admiral Moffett was, however, in a precarious position regarding the future of naval aviation following the Great War. On one hand he faced opposition from a strong lobby of traditional admirals known as the “gun club” who favored the development of the battleship as the primary weapon of the Navy. These “battleship” admirals hoped to maintain the supremacy of the surface fleet in the wake of the postwar cutbacks in budget that the Navy then faced. Most of theses conservative naval leaders saw naval aviation as a dangerous rival to their beloved battleships, and hardly deserving of a share of the meager funds allocated to the fleet following the war.

Equally difficult for Moffett was the challenge posed by the “prophets” of air power such as General William “Billy” Mitchell, who was so impressed by the potential of aircraft that he was calling for the formation of an exclusive independent air force. For Moffett, with his dreams of a strong naval aviation branch, Mitchell’s idea of an independent air force was totally unacceptable. What was needed for all sides was an opportunity to prove the validity of their positions in some kind of test of doctrines and the potential of aircraft.

June 21, 1921 was a warm, balmy day, and the group of military and civilian observers who were gathered for the demonstration was impatient for the experiment to begin. The potential of aerial bombardment was to be tested on a surrendered German battleship that the Navy had provided as a target. Admirals who favored the big-gunned dreadnoughts hoped that the exercise would be a failure, thus dooming once and for all the aircraft in future wars to the role of scouting for the still-supreme battleship. For others there was an air of expectancy to see if the new “prophet” of air power, General Mitchell, would be able to make good his boasts; he had promised in the newspapers that his experimental bombardment group would sink any battleship afloat.

Not to be outdone in this war of words, pugnacious Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels offered to stand bare-headed on the bridge of any ship that Mitchell chose to bomb. Seemingly his confidence was not misplaced because the Ostfriesland, the target, had already survived not only the worst that the Royal Navy could throw at it during the battle of Jutland in World War I but also 52 bomb hits inflicted by US Navy and Marine aircraft the day before.

The 1st Provisional Air Brigade led by Mitchell arrived over Hampton Roads and began its bombing run. Flying the awkward Martin bombers at an altitude of 1,100 feet, the brigade managed to sink the Ostfriesland with just 11 bombs. Naval planners like Moffet were pleased with the results of the tests to the extent that they had shown in a very public way that military aircraft had great potential in naval warfare. The trick, however, was to keep the Navy’s aviation branch independent of any combined “air force.” In order to forestall this unfortunate development, Admiral Moffett was able to develop a plan for a new combined fleet of heavy and light ships in which the aircraft carrier would play a central part in all strategic situations. Fortunately for Admiral Moffett and his allies, General Mitchell became an unwitting ally in their cause of naval aviation when his undisciplined criticism of his own superiors resulted in his court-martial and suspension from the service in 1925. Henceforth naval aviation would develop as an important integral part of the US Navy, with less hindrance from both the “gun club” and the proponent of a combined service air force.

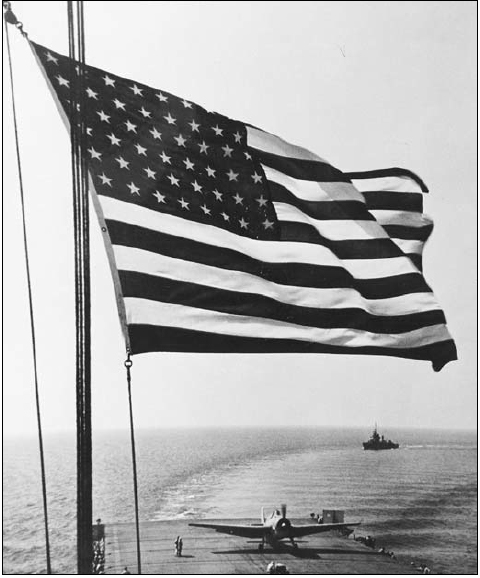

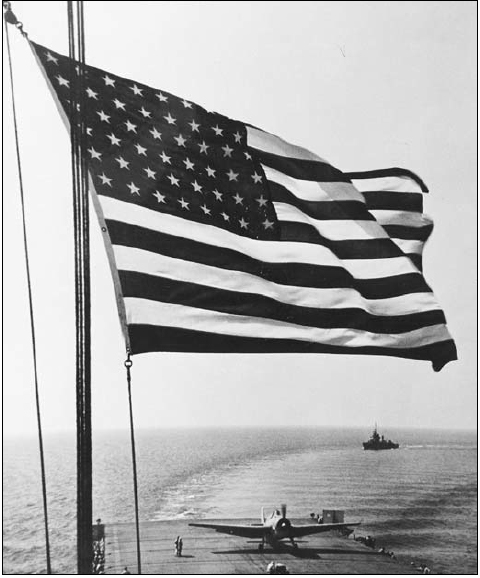

“Old Glory” waves over the flight deck of the USS Santee CVE 29 (Sangamon class) in this November of 1942 photograph as a General Motors TBM “Avenger” runs up its engine prior to air operations. Of primary interest is the narrow width of the flight deck of the CVE “Jeep” carriers. (National Archives)