The real beginning of naval aviation training for World War II may be traced back to the Great Depression with the passing of the Naval Aviation Cadet Act of 1935. This legislation was part of the “New Deal” policies of President Roosevelt, designed in part to keep the struggling American civil aviation business on its feet as well as increasing the number of potential naval aviators. The central feature of this legislation was the training of reserve officers for the Navy and Marine Corps by providing one year of flight instruction and three years of active duty to qualified college graduates between the ages of 18 and 28.

Air-minded officers saw the changes made in the recruitment and training of naval aviators by the Naval Aviation Cadet Act as an improvement on the previous methods of training. Under the old system only graduates of the US Naval Academy at Annapolis were able to qualify for training as naval aviators and then only after they had served two years with the Fleet as line officers. This stipulation caused many career-minded officers to think twice about an application to a program that would reduce them to the status of trainee. Although precise numbers for this period are very difficult to obtain, the new system turned out fewer, often far fewer, than 100 aviators a month. In 1935, the only year for which figures are available, the entire combined USN and USMC complement of aviators was less than 1,000 pilots, with only 1,500 aircraft of all types.

The first Aviation Cadets, or “AvCads” as they were called, received approximately 800 hours of combined flight instruction and ground school prior to “getting their wings.” One major drawback of the new AvCad program was the stipulation that the new pilots serve two years in the Fleet as cadets prior to obtaining commissions in the Navy as ensigns. This feature had been inserted into the program by the Navy partially to alleviate the difficulties of rank senority between the graduates of the Naval Academy and the new AvCads. Under this new system the aviation cadets would be at an age disadvantage for all future promotions vis-à-vis their regularly commissioned brother officers, who would have two full years’ seniority over them. The result of course was that the AvCad program failed to attract as many individuals as the Navy wanted.

By the end of 1938 the numbers of naval aviators had been raised to only 1,800 with something over 2,100 aircraft. Modifications to the AvCad program came in 1938 with the introduction of the Naval Aviation Cadet Act. This vital piece of legislation reduced flight training from 12 to six months, limited the ground school from 33 weeks to 18 weeks, and at last gave the new AvCads direct commissions immediately following graduation from flight training.

Let us follow the progress of a typical, though imaginary, potential pilot, John Wright, on the long road to becoming a naval aviator. As a young boy during the twenties in the era of “barn-storming,” a whole generation of young Americans fell in love with the romance of aviation. Raised on the stories of “Captain Eddy”(Captain Edward Rickenbacker) and the exploits of the “Lone Eagle” Charles Lindbergh, these young college students were eager to share in the glory of the exploration of the air.

For a young man like John, his initial flight instruction might have come from the Civilian Aeronautics Authority Civilian Pilot Training Program, or CAA-CPT. This program started in 1939 at 12 colleges around the country and was designed to increase the number of potential pilots in case war broke out. The class cost was minimal, about $25, and provided the trainee 40 hours of flight time in small civilian planes and about 70 hours of ground school. At the end of the course the student took a basic flight test with a CAA inspector and received his private pilot’s license. The CPT did not require the new pilots to assume a military obligation, but it did provide the basis for many new aviators’ entry into the military as December 1941 approached.

Many young men (65,000 by 1945) like John Wright began their military career at one of the nation’s Naval Reserve Air Bases (NRABs). Known as “E bases” by the trainees (“E” for elimination, because the failure rate was as high as 30 percent among the new pilots), the trainees received 30 days of flight instruction as seaman recruits. The cadet candidates, who had to have completed a minimum of two years at college and have logged at least 10 hours of flight time, were subjected to a series of physical and basic educational tests in what was essentially a “boot” camp designed to weed out those clearly unfit to be pilots or officers.

Intermediate flight training of AvCads continued in the North American SNJ Texan, an advanced flight trainer. These pilots walk across the tarmac at NAS Pensacola in early June 1942, geared up in their parachutes. (National Archives)

At the E base the new seaman recruits were taught the basics of aviation, such as the names of the various parts of an aircraft. Close-order drill was taught, as well as the basics of military discipline. The curriculum of the E base included engine repair, radio and Morse Code skills, and some lessons in elementary navigation and instrument flying. The E bases concentrated on training for military life at the expense of aviation; as one future naval aviator put it, the recruits learned more about washing down airplanes and cleaning heads (latrines) than they did about flying.

As the need for pilots grew so did the need for aviation mechanics. This USN WAVE (US Navy woman mechanic) works on the radial engine of one of the training command’s “Yellow Peril” floatplanes c.1942–43 (National Archives)

Having completed his E-base training, Seaman Wright was then sent on the second part of his program to become a naval aviator, Naval Air Basic Training at NAS Pensacola, the “cradle of naval aviation.” Here the aviator hopeful was discharged as a seaman and enrolled as a naval air cadet. Cadet Wright was signed to a contract under which he was to receive the sum of $75 a month plus room, board, and uniforms.

Discipline for the young cadets was a delicate situation; technically they were neither officers nor enlisted men, yet by naval tradition they were entitled to be called “Mister” and treated like gentlemen. In the prewar Navy, with its strong traditions of anti-fraternization with enlisted men, the AvCad defied categorization, being neither fish nor fowl as it were. Coupled with the fact that there were also enlisted pilots in the service, known by the rank of Naval Air Pilot (NAP) rather than the more prestigious Naval Aviator, some surface force officers had a difficult time relating to the aviation branch officers who had such close dealings with both mechanics and NAPs.

While at NAS Pensacola a new cadet like John Wright would pass through three separate squadrons where he would advance from basic to advanced levels. In the Navy the philosophy was and is that the naval aviator must be more than a pilot: he must also have a working knowledge of both the theory and the mechanics of aircraft. Classes were given in navigation, communication, engines, and meteorology as part of the ground school curriculum (academic classes of non-flying nature). Eventually the new aviator would be able to master all aspects of flying and the maintenance of aircraft. According to several sources the training at Pensacola was like several years of graduate-level work at a university due to the advanced nature of the classes given to the AvCads in such a short period of time.

For John and the other new AvCads the flight training began with primary instruction in land-based aircraft that was to last three months; this was where the cadet was introduced to the N3N basic trainer. Up to this point in his career Cadet Wright had flown in small, easy-to-fly aircraft like the Piper J-3 Cub, a high-wing, fabric-covered monoplane with a 50 hp engine. The N3N, also known as the “Yellow Peril” with its 300 hp engine, was a different proposition altogether, being a fully acrobatic biplane. The nickname “Yellow Peril” was based in part on the plane’s bright shade of yellow paint, but it also referred to the very real possibility that many new cadets were likely to be in peril of “washing out” of the program.

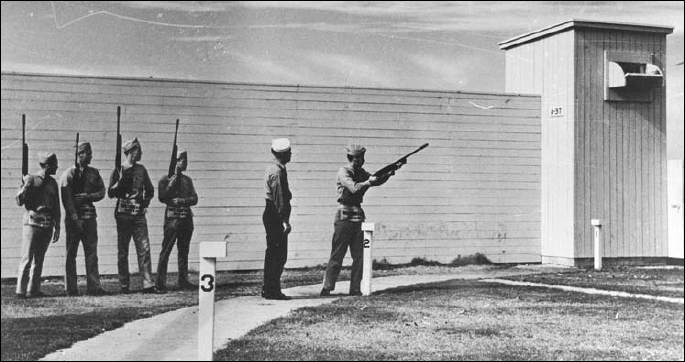

One of the most common forms of teaching the principles of aerial gunnery took place on the skeet range. For the rear seat gunners this practice often continued well into the cruise, with skeet competitions being held off the “fantail” of the ship. (National Archives)

In primary flight instruction the cadets were taught the rudiments of flying, with tests or “checks” being given at 20, 40, and 60 hours flying time by instructors known as “check pilots.” These check flights were designed to monitor the progress of the cadets in the vital skills of flying such as recovering the plane from a stall and basic air maneuvers like takeoffs and landings.

One of the major complaints of the cadets was the highly subjective nature of the grading during the check flights. In order to get a passing score the cadet needed to perform the required maneuver so as to satisfy his instructor as to the cadet’s competence as a pilot. These check pilots, being former AvCads themselves who upon graduation had been assigned the less than desirable duty of flight instruction, were apt to be difficult to please.

Following his check flight Cadet Wright, who had received an “up” check, was allowed to go on in his instruction. Those of his comrades who were given a “down” check were assigned additional study time before being given a second chance to pass the test prior to washing out of the program. In total the primary squadron gave the fledgling pilots 90 to 100 hours flight time in which to master the basics of flight.

If he was lucky, the next step in the training process for Cadet John Wright was the second squadron known as intermediate flight instruction, where he was taught formation flying and aerobatics. Intermediate flight instruction lasted four months. At this point the cadet began to specialize in aircraft of his own choosing, such as floatplanes, multi-engine aircraft, or, the most prized of all, carrier aircraft. Ground school instructions became more difficult with the introduction of more advanced concepts of navigation and radio communication, and the number of solo hours of flying was increased to 160. Likewise, training flights were now conducted in larger and more powerful aircraft, like the SNV Valiant (known as “the Vibrator”) and the famous North American SNJ Texan, both of which were low-wing monoplanes with engines rated at 600 hp.

During this intermediate phase of training Cadet Wright would be evaluated and selected for one of the three types of flying duty to which a new ensign could be assigned: multi-engine (VP), battleship/cruiser (VO) training, or carrier (VC) training. The evaluation of the cadets was based on their perceived strengths as noted by their instructors and by the preferences stated by the trainees themselves. Of all the possible choices, the VC squadrons were the ones that the cadets wanted to join, being the most glamorous and flying the Navy’s newest aircraft.

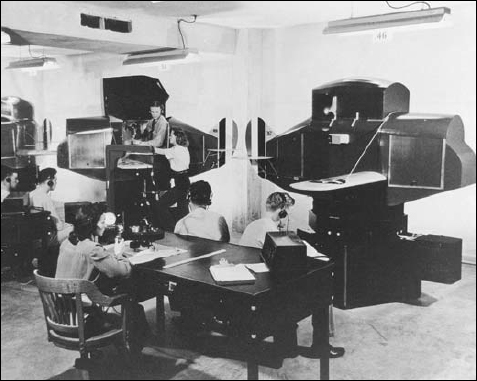

Following a successful up-check from the intermediate squadron, Naval Air Cadet Wright entered the final stage of his training. The third squadron provided advanced or what was known as operational training to the cadets. Instruction in instrument flying was supplemented, with the student being introduced to the notorious “black box,” the link trainer. The link trainer was a small replica aircraft in which the trainee was seated; a technician could remotely control the link to simulate a variety of situations that could occur while flying on instruments. The cadet’s test was to control the link trainer in the same manner as he would an actual aircraft while on instruments, eventually landing the craft safely.

Much of the operational training for the carrier squadrons was done at NAS Opa-Locka near Miami, Florida, where the instructors were veteran Fleet pilots skilled in the arts of dive-bombing, gunnery, fighter tactics, and aerial navigation. Each of the advanced students was given opportunities to hone his skills in the areas of carrier operations, fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo bombers before final selections for squadron placement of the cadets were made.

The students were now given the rudiments of basic carrier procedures, touch-and-go landings, as well as simulated carrier deck landings with a painted deck on the actual runway. As Cadet Wright progressed, he was taught the basics of aerial gunnery by the use of a target device know as a “sleeve.” The target sleeve was towed at a speed of approximately 150 mph by another fighter aircraft, and the students would practice the art of deflection shooting, firing at a moving target from an angle. The bullets of the various gunners were tipped in different colors of paint in order to record more easily the hits scored by each respective cadet.

Hollywood played its part in the war effort. Here actor Robert Taylor poses in front of his SNJ Texan wearing the winter flying suit of the US Navy. (National Archives)

The second stage of the operational training allowed the cadets to try their hands at the art of dive-bombing. For this part of their training the cadets would fly the Curtiss SBC-3 “Helldiver,” the last of the Navy’s biplane attack craft. The “Helldiver” was an aging craft powered by a 750 hp engine that had a maximum speed of only 220 mph.

For the training exercise the target was a 50-foot bull’s eye within a 100-foot circle. Successful attacks required three out of five attempts within the ring to earn a passing score.

Torpedo practice was often dispensed with during operational training due to a lack of suitable available aircraft. Only recently had the Navy begun to make the Douglas TBD “Devastator” operational within the Fleet and very few of these craft were available to the training command. This missed opportunity for experience with the torpedo would cost the US Navy dearly in the initial stages of the carrier wars, since the Navy’s prewar torpedo was of a faulty design which extensive prewar training usage could well have revealed.

AvCads are instructed in the principles of instrument flying and radio communication in the link trainer, known as the “Black Box” (1942). (National Archives)

At the end of the operational training program, Cadet John Wright was at long last able to graduate and take on the title of naval aviator, with the rank of ensign. United States Naval tradition required that new officers gave a silver dollar for the first salute received. Many were earned by wily drill instructors as they gave their former charges their first salute on the way back from the graduation parade.

By the time of graduation the new ensign would already have been selected by his instructors for a specific type of assignment and would be given appropriate advanced training. For example, a carrier assignment would be in one of three types of carrier squadron: fighters (VF), dive-bombers (VB), or torpedo bombers (VT). Starting in 1941 the new aviators could also be assigned to a new type of combined squadron, the composite (VC), that flew all three types of carrier planes off the Navy’s new smaller carriers, the CVGs, or jeep carriers.

Prior to final assignment to a carrier-based squadron, however, the new aviator would receive further instruction at the advanced carrier-training group (ACTG). Here they would be evaluated by pilots of the Fleet and given the opportunity to “get some salt water on their wings,” i.e., qualify on carrier deck landings. Due to the increased need for carrier pilots with the outbreak of war, and in view of the paucity of training time, carrier qualification training was set at eight actual carrier landings.

On December 7, 1941 news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor reached all Fleet units by the shocking radio message “Air raid Pearl Harbor, this is no drill.” War was declared the next day on Japan and America’s aviators, like the rest of her military forces, would undergo the most difficult test they ever faced.