William T. Cooper, Three Species of Parrot (Psephotus) 1970

About Australian Parrots

So characteristic is their shape and structure that anyone can identify a parrot—perhaps not which species of parrot, but certainly that the bird is a member of the parrot family. It helps that parrots are often distinctive in behaviour or colour, or both. Whether cheerfully chattering among themselves or raucously announcing their presence from the treetops, sweeping by in busy flocks, malingering in cheeky gangs, or dangling acrobatically, they seem to enjoy life—their faces never less than engaging, always knowing.

On current count, the Australian parrots number 56 species, including those from the Australian offshore territories. A separation of the Western Ground Parrot from the Eastern has recently been proposed, and the parrots from Norfolk and Lord Howe islands are sometimes regarded as separate species. So, arguably, there may be as many as 58 species. It might seem strange that in 2013 it is not known exactly how many species there are, but new research and new techniques keep extending knowledge and there is always debate.

Although Australia’s parrots represent only about one sixth of the world’s parrot species, they are the most diverse assortment of species of any country and many species are in great abundance.

William T. Cooper, Three Species of Parrot (Psephotus) 1970

Ebenezer Edward Gostelow, The Little Lorikeet (Glossopsitta pusilla); Purple-crowned Lorikeet (Glossopsitta porphyrocephala) 1928

The archetypal parrot is a brilliantly coloured tropical species, and the tropics worldwide do indeed support the most species. But in Australia, parrots are found from the desert to the rainforest, from alpine habitats to lowlands, on the mainland and on islands far offshore, and from the dry tropics southwards to the subantarctic. Nor are all gaudily plumaged, indeed even the whitest and brightest are hued to blend with their environment: hidden amongst bright blossoms or all but invisible against the silvered glare of the sky.

The 14 cockatoos, which include the Galah and the Cockatiel, are a group of large, relatively plainly coloured species with mobile crests and powerful bills. Australia is their stronghold and just a few cockatoos occur on the islands to Australia’s north as far as the Philippines. The remaining 42 species, usually referred to as the parrots—which includes lorikeets, fig-parrots, rosellas and the budgerigar—are smaller and multi-hued. The unusual Norfolk Island Kaka may belong with this latter group, which has representatives spread (mainly) across the Southern Hemisphere.

Although they are a diverse group, suited to many environments, all parrots have a strong, broadish, down-curved bill, topped by a fleshy cere (the skin at the base of the upper beak), in which the nostrils are located. Most have short, sturdy legs and all have two toes forward and two back, for climbing, grasping, perching and, for some, holding food. The two ground-dwelling species, the Ground Parrot and the Night Parrot, have longer legs and flatter feet and claws.

Australia’s smallest parrot is the Budgerigar, weighing just 20 grams and with a total length of 18 centimetres, most of which is tail. At a diminutive 14 to 15 centimetres, the Little Lorikeet and Fig-Parrot are shorter but they have short tails and stocky bodies so that they weigh considerably more, between 35 and 40 grams. At the other end of the scale are the powerful Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo and Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo, weighing as much as 900 grams and with a length of 60 centimetres.

All the Australian parrots have features that accentuate their face, whether a flamboyant crest or a conspicuously coloured or patterned bill, eyes, cheeks or forehead. The sexes are often similar but the female is slightly smaller. When they do differ, generally the male is more boldly coloured or has a brighter eye or eye-skin and/or bill, and the immature birds most resemble the female. An exception, at least to the human eye, is the Eclectus Parrot in which the females are red and blue while the males are largely green, although the male has a bright orange bill whereas the female’s is black.

Betty Temple Watts, Gang-gang Cockatoo 1958 (adult male, left; adult female, right)

Parrots can often be seen and even approached when feeding, whether scouring the ground for grains or corms, stripping grass seed from a delicate blade, gorging in blossom-laden bushes or chewing doggedly on foot-held, seemingly impenetrable nuts. The cockatoos are equipped to eat tougher, larger food items than the other parrots. They eat seeds, nuts, berries, fruits, blossoms, corms and roots, palm shoots and invertebrates, especially wood-boring larvae of moths and beetles which they dig out from the wood and bark. The smaller parrots eat seeds and grain, green vegetation, fruit, nectar, pollen and small invertebrates.

The parrots are sociable birds and occur in pairs or flocks some or all of the year, and occasionally in vast flocks of thousands. Three species are migratory, a rarity in the parrot world. The Blue-winged Parrot, the Orange-bellied Parrot and the Swift Parrot breed between spring and summer in Tasmania and move to the mainland between autumn and winter for the non-breeding season. A few parrot species range widely or make more local seasonal movements, following food sources such a blossoming trees or seeding grasses or trees. The Gang-gang, for instance, breeds in the high country and moves to lower altitudes after the breeding season.

Most Australian parrots are seasonal breeders, timing egg-laying so that nestlings and especially fledglings are around when there is a seasonal flush in their food. A few species, especially those of the unpredictable inland, for example the Budgerigar, the Scarlet-chested Parrot and the Princess Parrot, mostly breed after rain, when conditions are good. The majority of parrots nest in holes in trees but a few (such as the Golden-shouldered Parrot and the Hooded Parrot) tunnel into terrestrial termite mounds.

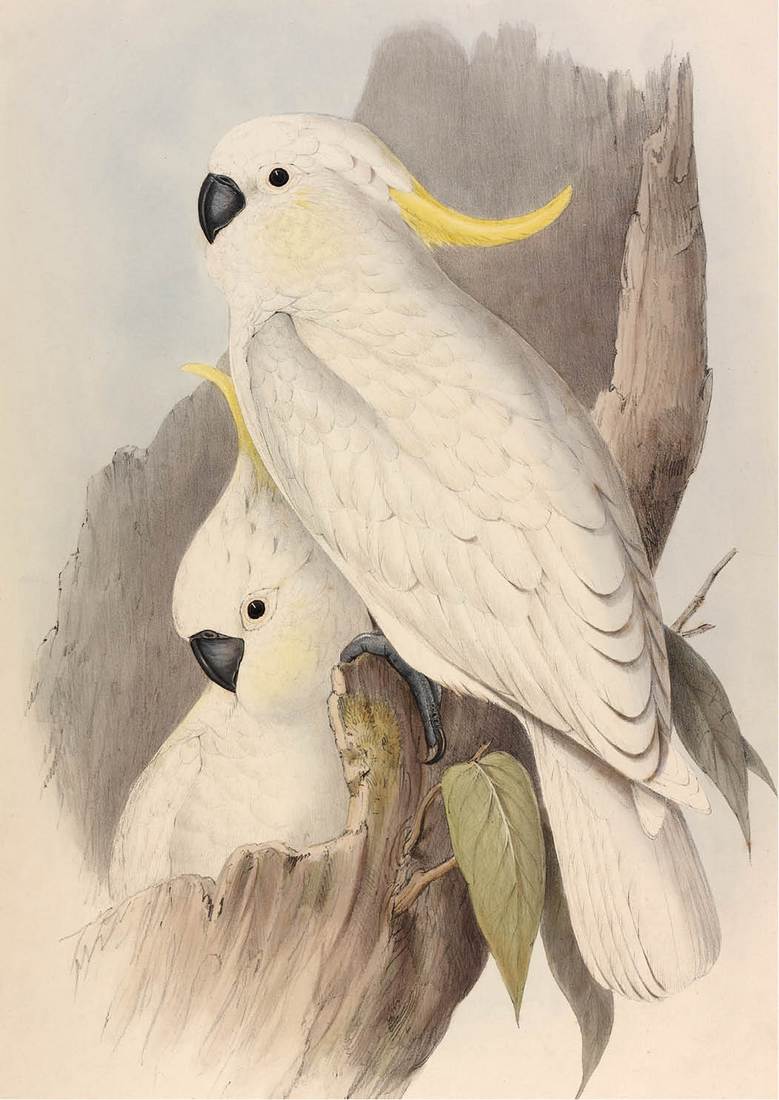

John Gould (artist), Henry Constantine Richter (lithographer), Crested Cockatoo (Cacatua galerita) 1848

Most species nest as scattered pairs but a few (for example, the Superb Parrot and the Regent Parrot) breed in a loose colony. Parrots’ eggs are white and unmarked, often round but occasionally elliptical in shape. The clutch size is largest in the species that nest in unpredictable climates, and ranges from two eggs in the biggest cockatoos to seven or so in the Budgerigar. The incubation period varies from about 18 days in the Budgerigar to four weeks in the large cockatoos. The nestlings remain in the nest and are fed by their parents for the first weeks of life—about four weeks in the Budgerigar and 12 weeks in the large cockatoos. By the time the nestlings fledge, they are about the same size as their parents. Budgerigar fledglings stay with their parents for a brief time while those of the larger cockatoos have an apprenticeship of many months. If conditions are right, Budgerigars are ready to breed at a few months of age, but four years is usual for the large cockatoos. Parrots can have a long life, ranging from 20 years for Budgerigars to 50 years for cockatoos. Of course, parrots in captivity are much more likely to attain maximum longevity than those in the wild.

Many parrots occur in great abundance and some have benefitted from crops and orchards and the provision of water or other food sources, so much so that they are sometimes regarded as pests. The two corellas, the Galah and the Rainbow Lorikeet are examples. Sadly, of the 56 Australian species, at least 12 (21 per cent) are extinct or threatened with extinction. The Norfolk Island Kaka, the Paradise Parrot from the Darling Downs area of Queensland and the Red-fronted Parakeet of Macquarie Island are gone forever. Another three species are perilously close to extinction—the Orange-bellied Parrot, the western subspecies of the Ground Parrot, and the Tasman Parakeet, which is extinct on Lord Howe Island but surviving on Norfolk Island. These species have reached this state because of human-related activities, mostly those that cause loss of habitat through clearing, over-grazing and drainage. Introduced predators such as rats and cats, and grazers such as rabbits take their toll, especially on islands.

Betty Temple Watts, Red-rumped Parrots 1959

EDITOR’S NOTE

In this book, the nomenclature and the taxonomic order of the bird species is the same as in Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds by Les Christidis and Walter E. Boles (Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing, 2008). The one exception is the extinct Norfolk Island Kaka, which Christidis and Boles place first taxonomically; however, we have followed other taxonomists by placing this species last, so as to start the portfolio of parrot illustrations on a positive note.

The distribution maps are based on those in the ninth edition of The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia by Graham Pizzey, illustrated by Frank Knight and updated and edited by Sarah Pizzey (Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 2012). The maps are shaded in the areas where a species regularly occurs; irregular occurrence is indicated by lighter shading.

In the following portfolio, the current common and scientific names of each species appear at the top of the section for that species. The caption for each illustration includes the species’ names (italicised) given by the artist at the time of the work’s creation. However, when the artist did not give the illustration a title, no title appears in the caption.

John Gould (artist), Henry Constantine Richter (lithographer), Psephotus multicolor (Many-coloured Parrakeet) 1848 (adult female)