Go knowledge learned by AlphaGo Zero. Courtesy of DeepMind

Artificial intelligence is not an objective, universal, or neutral computational technique that makes determinations without human direction. Its systems are embedded in social, political, cultural, and economic worlds, shaped by humans, institutions, and imperatives that determine what they do and how they do it. They are designed to discriminate, to amplify hierarchies, and to encode narrow classifications. When applied in social contexts such as policing, the court system, health care, and education, they can reproduce, optimize, and amplify existing structural inequalities. This is no accident: AI systems are built to see and intervene in the world in ways that primarily benefit the states, institutions, and corporations that they serve. In this sense, AI systems are expressions of power that emerge from wider economic and political forces, created to increase profits and centralize control for those who wield them. But this is not how the story of artificial intelligence is typically told.

The standard accounts of AI often center on a kind of algorithmic exceptionalism—the idea that because AI systems can perform uncanny feats of computation, they must be smarter and more objective than their flawed human creators. Consider this diagram of AlphaGo Zero, an AI program designed by Google’s DeepMind to play strategy games.1 The image shows how it “learned” to play the Chinese strategy game Go by evaluating more than a thousand options per move. In the paper announcing this development, the authors write: “Starting tabula rasa, our new program AlphaGo Zero achieved superhuman performance.”2 DeepMind cofounder Demis Hassabis has described these game engines as akin to an alien intelligence. “It doesn’t play like a human, but it also doesn’t play like computer engines. It plays in a third, almost alien, way. . . . It’s like chess from another dimension.”3 When the next iteration mastered Go within three days, Hassabis described it as “rediscovering three thousand years of human knowledge in 72 hours!”4

Go knowledge learned by AlphaGo Zero. Courtesy of DeepMind

The Go diagram shows no machines, no human workers, no capital investment, no carbon footprint, just an abstract rules-based system endowed with otherworldly skills. Narratives of magic and mystification recur throughout AI’s history, drawing bright circles around spectacular displays of speed, efficiency, and computational reasoning.5 It’s no coincidence that one of the iconic examples of contemporary AI is a game.

Games have been a preferred testing ground for AI programs since the 1950s.6 Unlike everyday life, games offer a closed world with defined parameters and clear victory conditions. The historical roots of AI in World War II stemmed from military-funded research in signal processing and optimization that sought to simplify the world, rendering it more like a strategy game. A strong emphasis on rationalization and prediction emerged, along with a faith that mathematical formalisms would help us understand humans and society.7 The belief that accurate prediction is fundamentally about reducing the complexity of the world gave rise to an implicit theory of the social: find the signal in the noise and make order from disorder.

This epistemological flattening of complexity into clean signal for the purposes of prediction is now a central logic of machine learning. The historian of technology Alex Campolo and I call this enchanted determinism: AI systems are seen as enchanted, beyond the known world, yet deterministic in that they discover patterns that can be applied with predictive certainty to everyday life.8 In discussions of deep learning systems, where machine learning techniques are extended by layering abstract representations of data on top of each other, enchanted determinism acquires an almost theological quality. That deep learning approaches are often uninterpretable, even to the engineers who created them, gives these systems an aura of being too complex to regulate and too powerful to refuse. As the social anthropologist F. G. Bailey observed, the technique of “obscuring by mystification” is often employed in public settings to argue for a phenomenon’s inevitability.9 We are told to focus on the innovative nature of the method rather than on what is primary: the purpose of the thing itself. Above all, enchanted determinism obscures power and closes off informed public discussion, critical scrutiny, or outright rejection.

Enchanted determinism has two dominant strands, each a mirror image of the other. One is a form of tech utopianism that offers computational interventions as universal solutions applicable to any problem. The other is a tech dystopian perspective that blames algorithms for their negative outcomes as though they are independent agents, without contending with the contexts that shape them and in which they operate. At an extreme, the tech dystopian narrative ends in the singularity, or superintelligence—the theory that a machine intelligence could emerge that will ultimately dominate or destroy humans.10 This view rarely contends with the reality that so many people around the world are already dominated by systems of extractive planetary computation.

These dystopian and utopian discourses are metaphysical twins: one places its faith in AI as a solution to every problem, while the other fears AI as the greatest peril. Each offers a profoundly ahistorical view that locates power solely within technology itself. Whether AI is abstracted as an all-purpose tool or an all-powerful overlord, the result is technological determinism. AI takes the central position in society’s redemption or ruin, permitting us to ignore the systemic forces of unfettered neoliberalism, austerity politics, racial inequality, and widespread labor exploitation. Both the tech utopians and dystopians frame the problem with technology always at the center, inevitably expanding into every part of life, decoupled from the forms of power that it magnifies and serves.

When AlphaGo defeats a human grandmaster, it’s tempting to imagine that some kind of otherworldly intelligence has arrived. But there’s a far simpler and more accurate explanation. AI game engines are designed to play millions of games, run statistical analyses to optimize for winning outcomes, and then play millions more. These programs produce surprising moves uncommon in human games for a straightforward reason: they can play and analyze far more games at a far greater speed than any human can. This is not magic; it is statistical analysis at scale. Yet the tales of preternatural machine intelligence persist.11 Over and over, we see the ideology of Cartesian dualism in AI: the fantasy that AI systems are disembodied brains that absorb and produce knowledge independently from their creators, infrastructures, and the world at large. These illusions distract from the far more relevant questions: Whom do these systems serve? What are the political economies of their construction? And what are the wider planetary consequences?

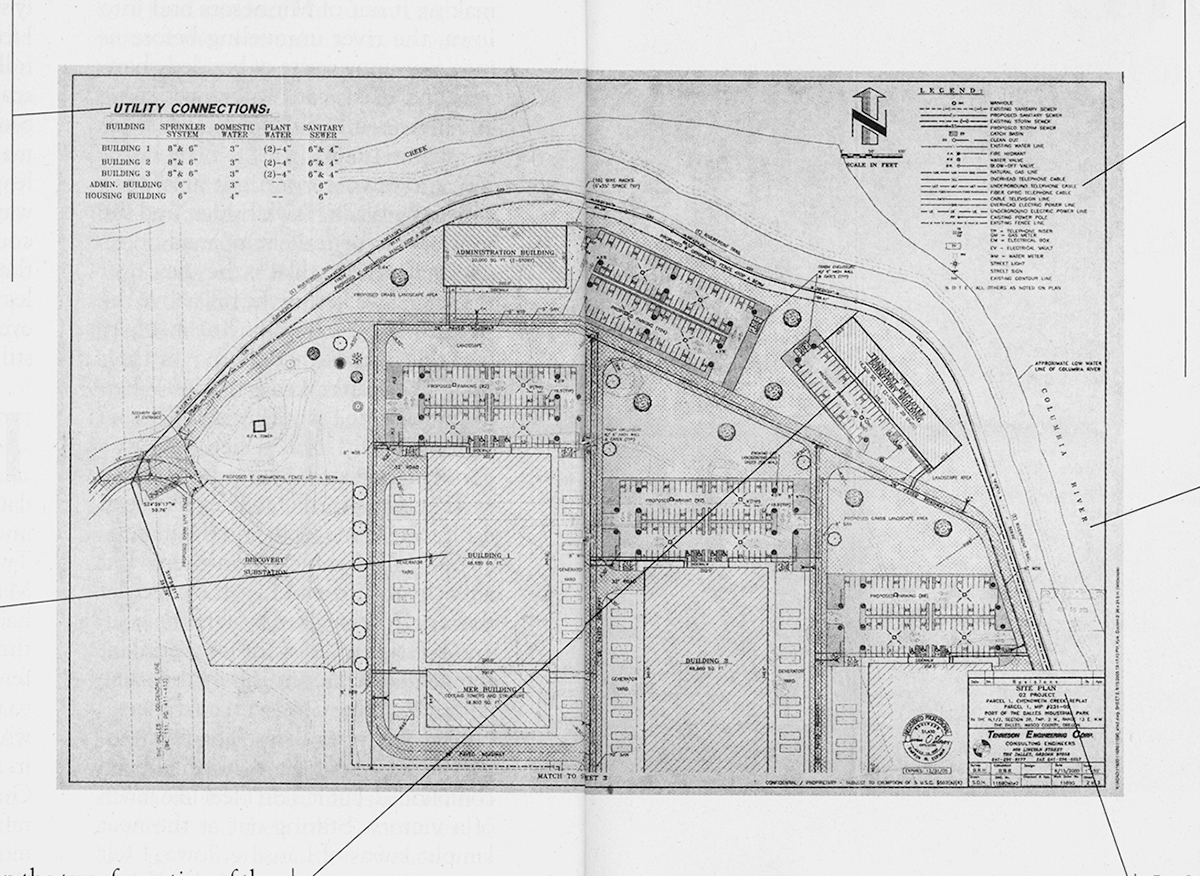

Consider a different illustration of AI: the blueprint for Google’s first owned and operated data center, in The Dalles, Oregon. It depicts three 68,680-square-foot buildings, an enormous facility that was estimated in 2008 to use enough energy to power eighty-two thousand homes, or a city the size of Tacoma, Washington.12 The data center now spreads along the shores of the Columbia River, where it draws heavily on some of the cheapest electricity in North America. Google’s lobbyists negotiated for six months with local officials to get a deal that included tax exemptions, guarantees of cheap energy, and use of the city-built fiber-optic ring. Unlike the abstract vision of a Go game, the engineering plan reveals how much of Google’s technical vision depends on public utilities, including gas mains, sewer pipes, and the high-voltage lines through which the discount electricity would flow. In the words of the writer Ginger Strand, “Through city infrastructure, state givebacks, and federally subsidized power, YouTube is bankrolled by us.”13

Blueprint of Google Data Center. Courtesy of Harper’s

The blueprint reminds us of how much the artificial intelligence industry’s expansion has been publicly subsidized: from defense funding and federal research agencies to public utilities and tax breaks to the data and unpaid labor taken from all who use search engines or post images online. AI began as a major public project of the twentieth century and was relentlessly privatized to produce enormous financial gains for the tiny minority at the top of the extraction pyramid.

These diagrams present two different ways of understanding how AI works. I’ve argued that there is much at stake in how we define AI, what its boundaries are, and who determines them: it shapes what can be seen and contested. The Go diagram speaks to the industry narratives of an abstract computational cloud, far removed from the earthly resources needed to produce it, a paradigm where technical innovation is lionized, regulation is rejected, and true costs are never revealed. The blueprint points us to the physical infrastructure, but it leaves out the full environmental implications and the political deals that made it possible. These partial accounts of AI represent what philosophers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri call the “dual operation of abstraction and extraction” in information capitalism: abstracting away the material conditions of production while extracting more information and resources.14 The description of AI as fundamentally abstract distances it from the energy, labor, and capital needed to produce it and the many different kinds of mining that enable it.

This book has explored the planetary infrastructure of AI as an extractive industry: from its material genesis to the political economy of its operations to the discourses that support its aura of immateriality and inevitability. We have seen the politics inherent in how AI systems are trained to recognize the world. And we’ve observed the systemic forms of inequity that make AI what it is today. The core issue is the deep entanglement of technology, capital, and power, of which AI is the latest manifestation. Rather than being inscrutable and alien, these systems are products of larger social and economic structures with profound material consequences.

How do we see the full life cycle of artificial intelligence and the dynamics of power that drive it? We have to go beyond the conventional maps of AI to locate it in a wider landscape. Atlases can provoke a shift in scale, to see how spaces are joined in relation to one another. This book proposes that the real stakes of AI are the global interconnected systems of extraction and power, not the technocratic imaginaries of artificiality, abstraction, and automation. To understand AI for what it is, we need to see the structures of power it serves.

AI is born from salt lakes in Bolivia and mines in Congo, constructed from crowdworker-labeled datasets that seek to classify human actions, emotions, and identities. It is used to navigate drones over Yemen, direct immigration police in the United States, and modulate credit scores of human value and risk across the world. A wide-angle, multiscalar perspective on AI is needed to contend with these overlapping regimes.

This book began below the ground, where the extractive politics of artificial intelligence can be seen at their most literal. Rare earth minerals, water, coal, and oil: the tech sector carves out the earth to fuel its highly energy-intensive infrastructures. AI’s carbon footprint is never fully admitted or accounted for by the tech sector, which is simultaneously expanding the networks of data centers while helping the oil and gas industry locate and strip remaining reserves of fossil fuels. The opacity of the larger supply chain for computation in general, and AI in particular, is part of a long-established business model of extracting value from the commons and avoiding restitution for the lasting damage.

Labor represents another form of extraction. In chapter 2, we ventured beyond the highly paid machine learning engineers to consider the other forms of work needed to make artificial intelligence systems function. From the miners extracting tin in Indonesia to crowdworkers in India completing tasks on Amazon Mechanical Turk to iPhone factory workers at Foxconn in China, the labor force of AI is far greater than we normally imagine. Even within the tech companies there is a large shadow workforce of contract laborers, who significantly outnumber full-time employees but have fewer benefits and no job security.15

In the logistical nodes of the tech sector, we find humans completing the tasks that machines cannot. Thousands of people are needed to support the illusion of automation: tagging, correcting, evaluating, and editing AI systems to make them appear seamless. Others lift packages, drive for ride-hailing apps, and deliver food. AI systems surveil them all while squeezing the most output from the bare functionality of human bodies: the complex joints of fingers, eyes, and knee sockets are cheaper and easier to acquire than robots. In those spaces, the future of work looks more like the Taylorist factories of the past, but with wristbands that vibrate when workers make errors and penalties given for taking too many bathroom breaks.

The uses of workplace AI further skew power imbalances by placing more control in employers’ hands. Apps are used to track workers, nudge them to work longer hours, and rank them in real time. Amazon provides a canonical example of how a microphysics of power—disciplining bodies and their movement through space—is connected to a macrophysics of power, a logistics of planetary time and information. AI systems exploit differences in time and wages across markets to speed the circuits of capital. Suddenly, everyone in urban centers can have—and expects—same day delivery. And the system speeds up again, with the material consequences hidden behind the cardboard boxes, delivery trucks, and “buy now” buttons.

At the data layer, we can see a different geography of extraction. “We are building a mirror of the real world,” a Google Street View engineer said in 2012. “Anything that you see in the real world needs to be in our databases.”16 Since then, the harvesting of the real world has only intensified to reach into spaces that were previously hard to capture. As we saw in chapter 3, there has been a widespread pillaging of public spaces; the faces of people in the street have been captured to train facial recognition systems; social media feeds have been ingested to build predictive models of language; sites where people keep personal photos or have online debates have been scraped in order to train machine vision and natural language algorithms. This practice has become so common that few in the AI field even question it. In part, that is because so many careers and market valuations depend on it. The collect-it-all mentality, once the remit of intelligence agencies, is not only normalized but moralized—it is seen as wasteful not to collect data wherever possible.17

Once data is extracted and ordered into training sets, it becomes the epistemic foundation by which AI systems classify the world. From the benchmark training sets such as ImageNet, MS-Celeb, or NIST’s collections, images are used to represent ideas that are far more relational and contested than the labels may suggest. In chapter 4, we saw how labeling taxonomies allocate people into forced gender binaries, simplistic and offensive racial groupings, and highly normative and stereotypical analyses of character, merit, and emotional state. These classifications, unavoidably value-laden, force a way of seeing onto the world while claiming scientific neutrality.

Datasets in AI are never raw materials to feed algorithms: they are inherently political interventions. The entire practice of harvesting data, categorizing and labeling it, and then using it to train systems is a form of politics. It has brought a shift to what are called operational images—representations of the world made solely for machines.18 Bias is a symptom of a deeper affliction: a far-ranging and centralizing normative logic that is used to determine how the world should be seen and evaluated.

A central example of this is affect detection, described in chapter 5, which draws on controversial ideas about the relation of faces to emotions and applies them with the reductive logic of a lie detector test. The science remains deeply contested.19 Institutions have always classified people into identity categories, narrowing personhood and cutting it down into precisely measured boxes. Machine learning allows that to happen at scale. From the hill towns of Papua New Guinea to military labs in Maryland, techniques have been developed to reduce the messiness of feelings, interior states, preferences, and identifications into something quantitative, detectable, and trackable.

What epistemological violence is necessary to make the world readable to a machine learning system? AI seeks to systematize the unsystematizable, formalize the social, and convert an infinitely complex and changing universe into a Linnaean order of machine-readable tables. Many of AI’s achievements have depended on boiling things down to a terse set of formalisms based on proxies: identifying and naming some features while ignoring or obscuring countless others. To adapt a phrase from philosopher Babette Babich, machine learning exploits what it does know to predict what it does not know: a game of repeated approximations. Datasets are also proxies—stand-ins for what they claim to measure. Put simply, this is transmuting difference into computable sameness. This kind of knowledge schema recalls what Friedrich Nietzsche described as “the falsifying of the multifarious and incalculable into the identical, similar, and calculable.”20 AI systems become deterministic when these proxies are taken as ground truth, when fixed labels are applied to a fluid complexity. We saw this in the cases where AI is used to predict gender, race, or sexuality from a photograph of a face.21 These approaches resemble phrenology and physiognomy in their desire to essentialize and impose identities based on external appearances.

The problem of ground truth for AI systems is heightened in the context of state power, as we saw in chapter 6. The intelligence agencies led the way on the mass collection of data, where metadata signatures are sufficient for lethal drone strikes and a cell phone location becomes a proxy for an unknown target. Even here, the bloodless language of metadata and surgical strikes is directly contradicted by the unintended killings from drone missiles.22 As Lucy Suchman has asked, how are “objects” identified as imminent threats? We know that “ISIS pickup truck” is a category based on hand-labeled data, but who chose the categories and identified the vehicles?23 We saw the epistemological confusions and errors of object recognition training sets like ImageNet; military AI systems and drone attacks are built on the same unstable terrain.

The deep interconnections between the tech sector and the military are now framed within a strong nationalist agenda. The rhetoric about the AI war between the United States and China drives the interests of the largest tech companies to operate with greater government support and few restrictions. Meanwhile, the surveillance armory used by agencies like the NSA and the CIA is now deployed domestically at a municipal level in the in-between space of commercial-military contracting by companies like Palantir. Undocumented immigrants are hunted down with logistical systems of total information control and capture that were once reserved for extralegal espionage. Welfare decision-making systems are used to track anomalous data patterns in order to cut people off from unemployment benefits and accuse them of fraud. License plate reader technology is being used by home surveillance systems—a widespread integration of previously separate surveillance networks.24

The result is a profound and rapid expansion of surveillance and a blurring between private contractors, law enforcement, and the tech sector, fueled by kickbacks and secret deals. It is a radical redrawing of civic life, where the centers of power are strengthened by tools that see with the logics of capital, policing, and militarization.

If AI currently serves the existing structures of power, an obvious question might be: Should we not seek to democratize it? Could there not be an AI for the people that is reoriented toward justice and equality rather than industrial extraction and discrimination? This may seem appealing, but as we have seen throughout this book, the infrastructures and forms of power that enable and are enabled by AI skew strongly toward the centralization of control. To suggest that we democratize AI to reduce asymmetries of power is a little like arguing for democratizing weapons manufacturing in the service of peace. As Audre Lorde reminds us, the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.25

A reckoning is due for the technology sector. To date, one common industry response has been to sign AI ethics principles. As European Union parliamentarian Marietje Schaake observed, in 2019 there were 128 frameworks for AI ethics in Europe alone.26 These documents are often presented as products of a “wider consensus” on AI ethics. But they are overwhelmingly produced by economically developed countries, with little representation from Africa, South and Central America, or Central Asia. The voices of the people most harmed by AI systems are largely missing from the processes that produce them.27 Further, ethical principles and statements don’t discuss how they should be implemented, and they are rarely enforceable or accountable to a broader public. As Shannon Mattern has noted, the focus is more commonly on the ethical ends for AI, without assessing the ethical means of its application.28 Unlike medicine or law, AI has no formal professional governance structure or norms—no agreed-upon definitions and goals for the field or standard protocols for enforcing ethical practice.29

Self-regulating ethical frameworks allow companies to choose how to deploy technologies and, by extension, to decide what ethical AI means for the rest of the world.30 Tech companies rarely suffer serious financial penalties when their AI systems violate the law and even fewer consequences when their ethical principles are violated. Further, public companies are pressured by shareholders to maximize return on investment over ethical concerns, commonly making ethics secondary to profits. As a result, ethics is necessary but not sufficient to address the fundamental concerns raised in this book.

To understand what is at stake, we must focus less on ethics and more on power. AI is invariably designed to amplify and reproduce the forms of power it has been deployed to optimize. Countering that requires centering the interests of the communities most affected.31 Instead of glorifying company founders, venture capitalists, and technical visionaries, we should begin with the lived experiences of those who are disempowered, discriminated against, and harmed by AI systems. When someone says, “AI ethics,” we should assess the labor conditions for miners, contractors, and crowdworkers. When we hear “optimization,” we should ask if these are tools for the inhumane treatment of immigrants. When there is applause for “large-scale automation,” we should remember the resulting carbon footprint at a time when the planet is already under extreme stress. What would it mean to work toward justice across all these systems?

In 1986, the political theorist Langdon Winner described a society “committed to making artificial realities” with no concern for the harms it could bring to the conditions of life: “Vast transformations in the structure of our common world have been undertaken with little attention to what those alterations mean. . . . In the technical realm we repeatedly enter into a series of social contracts, the terms of which are only revealed after signing.”32

In the four decades since, those transformations are now at a scale that has shifted the chemical composition of the atmosphere, the temperature of Earth’s surface, and the contents of the planet’s crust. The gap between how technology is judged on its release and its lasting consequences has only widened. The social contract, to the extent that there ever was one, has brought a climate crisis, soaring wealth inequality, racial discrimination, and widespread surveillance and labor exploitation. But the idea that these transformations occurred in ignorance of their possible results is part of the problem. The philosopher Achille Mbembé sharply critiques the idea that we could not have foreseen what would become of the knowledge systems of the twenty-first century, as they were always “operations of abstraction that claim to rationalize the world on the basis of corporate logic.”33 He writes: “It is about extraction, capture, the cult of data, the commodification of human capacity for thought and the dismissal of critical reason in favour of programming. . . . Now more than ever before, what we need is a new critique of technology, of the experience of technical life.”34

The next era of critique will also need to find spaces beyond technical life by overturning the dogma of inevitability. When AI’s rapid expansion is seen as unstoppable, it is possible only to patch together legal and technical restraints on systems after the fact: to clean up datasets, strengthen privacy laws, or create ethics boards. But these will always be partial and incomplete responses in which technology is assumed and everything else must adapt. But what happens if we reverse this polarity and begin with the commitment to a more just and sustainable world? How can we intervene to address interdependent issues of social, economic, and climate injustice? Where does technology serve that vision? And are there places where AI should not be used, where it undermines justice?

This is the basis for a renewed politics of refusal—opposing the narratives of technological inevitability that says, “If it can be done, it will be.” Rather than asking where AI will be applied, merely because it can, the emphasis should be on why it ought to be applied. By asking, “Why use artificial intelligence?” we can question the idea that everything should be subject to the logics of statistical prediction and profit accumulation, what Donna Haraway terms the “informatics of domination.”35 We see glimpses of this refusal when populations choose to dismantle predictive policing, ban facial recognition, or protest algorithmic grading. So far these minor victories have been piecemeal and localized, often centered in cities with more resources to organize, such as London, San Francisco, Hong Kong, and Portland, Oregon. But they point to the need for broader national and international movements that refuse technology-first approaches and focus on addressing underlying inequities and injustices. Refusal requires rejecting the idea that the same tools that serve capital, militaries, and police are also fit to transform schools, hospitals, cities, and ecologies, as though they were value neutral calculators that can be applied everywhere.

The calls for labor, climate, and data justice are at their most powerful when they are united. Above all, I see the greatest hope in the growing justice movements that address the interrelatedness of capitalism, computation, and control: bringing together issues of climate justice, labor rights, racial justice, data protection, and the overreach of police and military power. By rejecting systems that further inequity and violence, we challenge the structures of power that AI currently reinforces and create the foundations for a different society.36 As Ruha Benjamin notes, “Derrick Bell said it like this: ‘To see things as they really are, you must imagine them for what they might be.’ We are pattern makers and we must change the content of our existing patterns.”37 To do so will require shaking off the enchantments of tech solutionism and embracing alternative solidarities—what Mbembé calls “a different politics of inhabiting the Earth, of repairing and sharing the planet.”38 There are sustainable collective politics beyond value extraction; there are commons worth keeping, worlds beyond the market, and ways to live beyond discrimination and brutal modes of optimization. Our task is to chart a course there.