AS THE INK DRIED on The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates, the event it looked for with such eagerness took place with shocking speed. King Charles I was executed on 30 January 1649. For one New Model Army soldier, ‘… that the king is executed is good news to us: only some few honest men and a few cavaliers bemoan him,’ while others remained singularly unmoved: ‘A little before supper we saw a diurnal with news that the King was sentenced to die this night: I paid Mr Watson his five pounds for my black mare.’1 The soldier was wrong. Even those who would come to support the new regime were stunned by events. Bulstrode Whitelock, an MP who kept a fascinating day-by-day diary of events throughout these years, could not bring himself to make an entry on 29 January, such was his distress. The next day, Whitelock did not attend Parliament ‘but stayed all day at home, troubled at the death of the King this day, & praying to God to keep his judgements from us’.2 Fear accompanied shock as the nation struggled to absorb the execution of their King.

An eyewitness account of the execution captures the mood.

I stood amongst the crowd in the street before Whitehall gate where the scaffold was erected, and saw what was done, but was not so near as to hear any thing. The blow I saw given, and can truly say with a sad heart, at the instant whereof, I remember well, there was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again. There was according to Order one Troop immediately marching from Charing Cross to Westminster and another from Westminster to Charing Cross purposely to master the people, and to disperse and scatter them, so that I had much ado amongst the rest to escape home without hurt.3

The English people knew that they had witnessed a unique moment in history and wondered, fearfully, what would happen next. As soon has Charles’s head had been severed from his body, a contest for hearts and minds began, epitomised by rival interpretations of the crowd’s ‘groan’, one side hearing it as relief, the other sorrow. John Milton would play a crucial role in this battle over the coming months and years.

In the immediate aftermath of the execution, the Rump Parliament had some very practical concerns. Tellingly, the new regime decided that the mechanisms of execution should be removed as quickly as possible, as if the event had never happened. At the same time, they insisted that Charles’s body should be put on display to the public ‘that all men might know that he was dead’. Accordingly, in a show of respect not usually offered to those executed for treason, the body was embalmed after its head had been sewn back on.

The Rump moved more slowly when it came to enacting the constitutional reforms in the name of which it had executed the King. Through February and March, however, the necessary Acts were passed and the revolution completed. The monarchy was abolished. It was ruled that ‘the office was unnecessary, burdensome, and dangerous to the liberty, safety, and public interest of the people, and that for the most part, use hath been made of the regal power and prerogative to oppress and impoverish and enslave the subject’4 The House of Lords, the Privy Council and the Prerogative Courts were all abolished, and the Crown’s administrative departments (such as the Exchequer and the Admiralty) replaced by a Council of State. This Council would be supported by a raft of subcommittees with executive powers.

In an appeal to history, the new regime argued that the English nation had at last recovered ‘its just and ancient right, of being governed by its own representatives or national meetings in council, from time to time chosen and entrusted for that purpose by the people’. Just as Protestants had asserted that they were merely returning the Church to its original uncorrupt state, the new government was merely returning England to its ancient liberty. Finally, on 19 May 1649, the Act was passed declaring England a ‘Commonwealth and Free State’.

England was now the political new world. Over the preceding centuries, various Italian city-states had flirted with republicanism (Venice had been the longest-lasting, Florence had the purest form). Milton, and those of his contemporaries who travelled, might have known the system at first hand on a small scale. They would certainly have read the theory of republicanism, whether in the words of Classical Livy or Renaissance Machiavelli. But it was one thing to read about a political system, or to travel for a month to Venice, another thing to fight a civil war, and to establish a viable republic based on clear anti-monarchical principles. This is what the Rump Parliament did, and there were few who followed their lead until the late eighteenth century.

It did not make England popular in 1649. Throughout Europe, monarchies looked warily at the example of the Commonwealth. Within and beyond the nation’s borders, there were many who immediately started working for the counter-revolution. The threat to the Commonwealth was real and urgent, as recognised in the Act for the abolishing of monarchy, in which there were fearsome warnings of what would happen to anyone who tried ‘by force of arms or otherwise’ to aid, assist, comfort or abet ‘any person or persons’ who supported the ‘setting up again of any pretended right of the said Charles, eldest son to the said late King, James called Duke of York, or of any other the issue and posterity of the said late King’. There is much more of the same. The Act sought to cover any eventuality, and promised ‘the same pains, forfeitures, judgements, and execution as is used in case of high treason’ to those who challenged the Rump’s authority to govern. In other words, the Act told the English people, support any attempt to reinstate monarchy, and you die.

Despite these threats, there were many willing to support the executed King’s two sons, Charles and James Stuart, who were still very much alive. Over the next two years, resistance in Ireland in particular proved vicious and prolonged. Henry Ireton, a leading military commander and Cromwell’s son-in-law, lost his life at the terrible siege of Limerick, but eventually and bloodily, Cromwell’s armies eradicated opposition. There remained the problem of Charles Stuart, who on 1 January 1651 had been crowned King of Scotland, and by September had led an army as far south as Worcester. But Charles’s forces were routed in battle there, and the would-be King fled to France. The military threat to the new republic was being dealt with: after all, this was a revolution based on Cromwell’s success on the battlefield.

There was, however, a more insidious internal threat to the new regime. Many individuals had expected more, much more, of the revolution. Many would be disappointed in their hopes for religious, social or political change. John Milton in the early months of 1649 was among them.

Most of the more radical religious groups discovered fairly quickly that there was no room for their views in the Commonwealth. At first, hopes were high. In the aftermath of Charles’s execution, Fifth Monarchists like John Owen (Cromwell’s chaplain) believed even more fervently that the Apocalypse was imminent. If only the rule of the saints could be established in England, then God would ‘sooner or later shake all the Monarchies of the Earth’. Another group of religious extremists, the Ranters, were successfully recruiting from the London poor: ‘No matter what scripture, saints or churches say, if that within thee do not condemn thee, thou shalt not be condemned,’ argued the Ranter Laurence Claxton in 1650. Abiezer Coppe, prosecuted in 1651 for asserting that ‘there is no sin’, that ‘there is no God’, ‘that God is in man, or in the creature only, and no where else’, expressed the Ranters’ antinomianism.5 Many Ranters went further and believed that an individual attained perfection through sinning. The aim was to enact a sin as ‘no-sin’, and the result was a complete rejection of the family unit, the bedrock of seventeenth-century life: ‘Give over thy stinking family duties’ was the Ranter command.6

Other sects, perhaps understandably, distanced themselves from the Ranters while sharing their antinomianism. The Quaker George Fox took care to argue that he was clear of sin because of the love of Jesus Christ, but that did not mean he was actually Jesus Christ: ‘Nay, we are nothing. Christ is all.’7 Nevertheless, Fox received a six-month imprisonment for his blasphemy, ‘contrary to the late act of Parliament’.

The ‘late act’ that convicted Fox was Parliament’s response to the religious radicals and merely fuelled disillusion with the revolution among these groups. Further Acts insisted on the observation of the Sabbath, authorised strong punishments for profane swearing or cursing, and, most shocking, instituted the death penalty for those who committed adultery, fornication or incest. Indeed, fear of the radical fringe meant that the Rump Parliament was extremely slow to overturn the statutes that compelled individuals to attend the national Church. It would wait nearly three years to introduce a limited form of religious toleration.

The more explicitly political radicals who welcomed the execution of the King and the abolishment of monarchy also had their hopes shattered in the early months of 1649. To many it seemed as if England had merely replaced a tyrannical monarchy with a tyrannical oligarchy, with government by one man replaced by government by an unaccountable élite. As the Leveller John Lilburne’s pamphlet of that year had it, he had England’s New Chains Discovered. Lilburne questioned ‘what now is become of that liberty that no man’s person shall be attached or imprisoned, or otherwise dis-eased of his Freehold, or free Customs, but by lawful judgements of his equals?’8 Disillusion led to demands for military action. Lilburne’s ally, Richard Overton, proposed that a joint council of officers and men from the New Model Army, who had, after all, achieved the removal of the King, should rule the country. Overton urged the soldiers and the people of England to fight for this cause.

Oliver Cromwell responded aggressively, but the funeral of one Trooper Lockyer, shot by Cromwell’s men, became something of a public demonstration of support for the Army. A hundred people walked in front of the corpse, which was decorated with bunches of rosemary for remembrance, stained with blood. Lockyer’s sword was laid upon his body. Soldiers on horseback followed, and then thousands of foot soldiers, wearing sea-green and black ribbons, green the colour of the Leveller movement, black a sign of respect. Behind the men came a procession of women. At Westminster, near the churchyard where Lockyer was to be buried, ‘some thousands more of the better sort’ joined the mourners, unwilling to march in the procession but keen to show their support. It was a remarkable and unprecedented display of political will.

There were more unprecedented political developments to come. The Levellers’ democratic ideals were rooted in their Christian beliefs: all men (and, even more remarkably, all women) were equal before God.9 And now it was the Leveller women’s turn to make their case to Parliament. Thousands of women, led by Lilburne’s wife, presented a special petition. They were told to go home and wash their dishes. The women replied that they had at home neither food nor dishes. The women’s Petition is a passionate and eloquent argument for all women’s common humanity with men, and a record of these particular women’s sufferings during wartime and beyond. Years of ‘unjust cruelties’ inspired them, but the execution of Robert Lockyer and the imprisonment of the Leveller leaders – ‘our friends in the Tower’, as the Petition put it – triggered their extraordinary action in 1649. Commanded to stay at home, the women invoked their Christian duty to speak out, to bear testimony:

Nay, shall such valiant, religious men as Mr. Robert Lockyer be liable to law martial, and to be judged by his adversaries, and most inhumanly shot to death? Shall the blood of war be shed in time of peace? Doth not the word of God expressly condemn it … And are we Christians, and shall we sit still and keep at home, while such men as have borne continual testimony against the injustice of all times and unrighteousness of men, be picked out and be delivered up to the slaughter …10

Parliament was not listening, could not listen, to such outrageous proto-feminist claims as these.

Nevertheless, a petition signed by 90,000 people, ‘Remonstrance of many thousands of the free people of England’, appeared in September, suggesting that the movement was thriving. In fact, the ‘Remonstrance’ was the Levellers’ death rattle. Their political ideas were far ahead of their time. More importantly, they faced the implacable opposition of Oliver Cromwell. Looking back, a few years later, at the state of the nation in 1649, Cromwell described it as ‘rent and torn in spirit and in principle from one end to another … family against family, husband against wife, parents against children, and nothing in the hearts and minds of men but “Overturning, overturning, overturning …”’11 His task, as he saw, was to stand firm against those who sought merely to ‘Overturn’, against those who pursued a ‘levelling principle’ that would ‘tend to the reducing of all to an equality’. For Cromwell, however, standing firm invariably meant violent action. As he warned his Council, ‘I tell you … you have no other way to deal with these men but to break them in pieces. If you do not break them, they will break you.’12

Cromwell’s determination to crush the Army Levellers was one factor in the movement’s collapse. Less violent but perhaps as effective, the Rump Parliament took care to pay the New Model soldiers, something the parliamentary leaders of 1646–7 had often failed to do. Once paid, many soldiers lost interest in their political ambitions: radicalism was perhaps not actually as deep-rooted in the Army as it first seemed.13

There was, however, a third grouping in the radical challenge to the new Commonwealth, a movement that reached beyond religious and political claims towards a complete revolution in the economic and social basis of English society. This movement had its beginnings in the particularly harsh economic conditions of the period from 1648 to 1650, when, in the face of grinding poverty and the threat of starvation, agrarian communities came together to farm common lands for food. The most famous of these ‘Digger’ communities was based at St George’s Hill in Surrey, and later at Cobham Heath, also in Surrey. Its leader was Gerard Winstanley, and his tract of 1649, The New Law of Righteousnes, demanded the return of all public lands to the people. Winstanley told his readers that he had received a simple but revolutionary message in a trance: ‘Work together, Eat bread together.’ The Surrey commune was his attempt to put his vision into practice. On common land, the Diggers grew corn, parsnips, carrots and beans. It did not take long for persecution to begin. The community was attacked and its buildings burned. Winstanley merely became more urgent in his pamphleteering, offering A Watch-word to the City of London and the Armie, in which he argued that freedom is won not given, and urging the people to take action on their own behalf. The utopian Digger movement, so much smaller than the Leveller movement (and condemned even by them), was, however, as doomed to destruction as all the other radical movements of the time. In the face of the hostility of local landowners, harassment by soldiers and lawsuits, the commune could not survive. There was no trace of the Diggers by July 1650.

As the Digger movement demonstrated, it was the poor who suffered most in these years of failed crops and uncertain government, but no one was exempt from at least some misery. The diarist John Evelyn recalled the freak weather conditions of 1648, a ‘most exceeding wet year, neither frost or snow all the winter for above six days in all, and cattle died of a murrain [infectious disease] every where’.14 The traditional response to hunger was to see it as God’s will, as the preacher Robert Wilkinson had advised corn rioters back in 1607: ‘Therefore, consider and see I beseech you, whence arise conspiracies, riots, and damnable rebellions; not from want of bread, but through want of faith, yea want of bread doth come by want of faith.’15 It remained to be seen whether the new republican Commonwealth would be any better than previous governments at delivering the poor from starvation, or whether the ‘want of bread’ would remain, conveniently, simply an incontrovertible sign of God’s displeasure with his people.

And what of John Milton? No Ranter or Digger, no Leveller or Quaker, Milton was nevertheless a disappointed man in the spring of 1649. He expressed his disappointment with the new regime by writing an astonishing fifty thousand words in six weeks, the first four chapters of his (admittedly already researched) History of Britain, together with a ‘Digression’ considering the state of the nation. The work would not be published for more than twenty years, but this was Milton’s response to the crisis of the English revolution, his History ‘just the swift review needed for historical instruction at a critical time’.16

Milton recognised that the country was at a transitional stage but feared that England was sliding back to its old political ways. Members of Parliament ousted by the Rump, those who had voted in favour of further negotiations with the King back in December 1648, were being allowed to return to Westminster, having conveniently changed their minds about their earlier decision. Milton in his ‘Digression’ lamented that the opportunity to establish republican government was being squandered within a month of the execution of the King. He was angry and fearful: ‘they who had the chief management’, who were ‘masters of their own choice, were not found able’ to create even the hope ‘of a just and well amended commonwealth to come’.17 As ever, Milton was worried about the condition of English manhood. The heat of the violent man, happy to start civil wars, could not be sustained and would turn to weakness; the cool temperance (not to mention the Classical and Mediterranean political thinking) needed to run a country was nowhere to be found.18

Just one fortnight after the execution of Charles, Milton had been happy to quote Seneca in the printed preface to his Tenure of Kings and Magistrates:

There can be slain

No sacrifice to God more acceptable

Than an unjust and wicked king.

Only a few weeks later, he was already wondering if it had all been worth it. Yet the sacrificial slaying of King Charles was to prove a turning point for Milton. Only six weeks after the execution, and four weeks after he had leapt back into print with his Tenure, he was invited by the new government to become Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the Council of State at a salary of £288 per annum. He accepted the position, a sign, perhaps, that his fear of political backsliding was transitory. Whether out of pragmatism or idealism, he joined forces with the new regime. If Bradshaw and Cromwell were indeed going to transform England into a beacon of republican good governance, then John Milton was going to be part of that transformation.

The Council needed someone to handle their diplomatic correspondence with foreign nations. Much of the correspondence would be in Latin, still the political lingua franca of Europe. They chose Milton. His talent for Latin was indisputable; his Tenure had established his political loyalty, even before Charles’s head had rolled; and his connection with John Bradshaw can have done no harm.

Bradshaw had not stopped at sentencing King Charles to death. Having chaired the high court of justice set up to try Royalist military leaders, on 14 February 1649 he became one of forty-one peers, politicians, judges and soldiers chosen by MPs to sit on the new Council of State. This Council would be the principal executive organ of the Commonwealth of England and Ireland. The day after the executions of the Royalist military leaders, Bradshaw was appointed Lord President of the Council by his colleagues, making him in effect England’s first elected executive head of state.

Whether Lord President Bradshaw pulled the necessary strings or not, John Milton was now the Council’s Secretary for Foreign Tongues. At last he was in a position to exploit all his linguistic abilities. Back in 1644 in his tract Of Education, he had worried about the poor Latin pronunciation of his fellow Englishmen: ‘For we Englishmen, being far northerly, do not open our mouths in the cold air wide enough to grace a southern tongue.’ Now he could, quite literally, open his mouth wide in the northern air, speak and write in Latin to the honour of his country. Crucially, Milton’s ability in Latin gave credibility to the new government: there were not too many highly educated intellectuals who would have served the Commonwealth in 1649. Milton was in a superb position to reply, intelligently and fluently, to the attacks that flowed from Catholic, monarchical Europe.

John Milton was where he wanted to be. His talents were now in the service of a political regime that he supported in principle, and all doubts were laid aside. Looking back at this period later, he wrote that he abandoned the pessimistic History in the face of his new responsibilities.19 He may have been writing to the Council’s orders, but he had a clear focus and a clear path ahead of him.

The Council quickly realised that Milton also had his uses as a propagandist. His first major assignment looked like familiar territory. He was asked to respond to a pamphlet. This was no ordinary pamphlet, however: it was Eikon Basilike (The King’s Image), a short work allegedly written by King Charles I himself. Eikon Basilike turned Charles I from a villainous and inept leader who had been rightfully removed from office, and from life, into a saintly figure, sanctioned by God himself to lead his country and martyred by vicious extremists. The pamphlet built on the indisputable fact that Charles had died well. Even his opponents had to admit that the King had demonstrated courage and firmness on the scaffold, the more surprising because these qualities were not natural to him. Some years later, the poet Andrew Marvell would capture the moment in a poem ostensibly in praise of the man who replaced Charles as leader, Oliver Cromwell:

He nothing common did or mean

Upon that memorable scene,

But with his keener eye

The axe’s edge did try:

Nor call’d the gods, with vulgar spite,

To vindicate his helpless right,

But bowed his comely head

Down, as upon a bed.20

To many, this composure revealed that God was with the King, something that Charles repeatedly pointed out in his comments on the scaffold.

Typical of Eikon Basilike’s religious tone is the chapter recounting Charles’s captivity at Holmby, which enabled him ‘to study the world’s vanity and inconstancy’. God sees ‘tis fit to deprive me of wife, children, army, friends, and freedom, that I may be wholly His, Who alone is all.’ The work ends with the King’s meditations on death, his prayers and the prophetic (or canny) comment that ‘the glory attending my death will far surpass all I could enjoy or conceive in life.’21

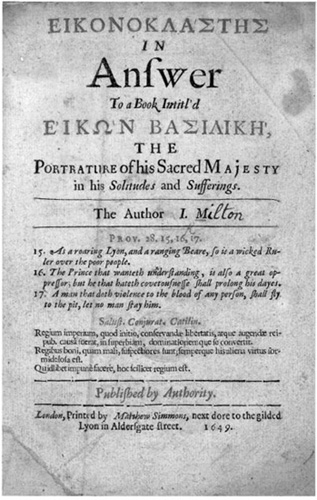

John Milton, who had already written so passionately in support of the legitimacy of removing the tyrannical Charles in his Tenure of Kings and Magistrates, rose to the challenge presented by Eikon Basilike. His reply was published on 6 October 1649 and entitled Eikonoklastes (The Image Destroyer). Milton used the technique he had first deployed in the early 1640s, whereby he took the very phrases of the enemy and turned them against him.

That I went, saith he of his going to the House of Commons, attended with some Gentlemen; Gentlemen indeed; the ragged infantry of stews and brothels; the spawn and shipwreck of taverns and dicing houses … The House of Commons upon several examinations of this business declared it sufficiently proved that the coming of those soldiers, Papists and others with the King, was to take away some of their Members, and in case of opposition or denial, to have fallen upon the House in a hostile manner. This the King here denies; adding a fearful imprecation against his own life, If he purposed any violence or oppression against the innocent, then, saith he, let the enemy persecute my soul, and tread my life to the ground and lay my honour in the dust. What need then more disputing? He appealed to God’s tribunal, and behold God hath judged, and done to him in the sight of all men according to the verdict of his own mouth.22

Eikonoklastes is not only a savage attack on Charles I, who whipped ‘all his Kingdoms’ with ‘his two twisted Scorpions, both temporal and spiritual tyranny’, and pursued ‘his private interest’ at all times, but a defence of the new political order: ‘For who should better understand their own laws, and when they are transgressed, than they who are governed by them, and whose consent first made them: and who can have more right to take knowledge of things done within a free nation, than they within themselves?’23 Milton’s reply became a rallying cry to the recently liberated nation. If they only had virtues such as piety, justice and fortitude, joined with contempt for avarice and ambition, then the people ‘need not Kings to make them happy, but are the architects of their own happiness’.24

It was an optimistic assessment of the English people, based on Milton’s belief in the necessity for shared government, an independent Church and the value of meritocracy. The benefits of a society should never again ‘come to be within the gift of any single person’. Yet the pamphlet’s closing sentences recognise that the image of King Charles that Milton had spent so many pages destroying still had power, if only over the ‘rabble’. There was hope, if the English people could just break the spell of monarchy and ‘recover’. Eikon Basilike might gain Charles

after death a short, contemptible, and soon fading reward; not what he aims at, to stir the constancy and solid firmness of any wise man, or to unsettle the conscience of any knowing Christian, if he could ever aim at a thing so hopeless, and above the genius of his cleric elocution, but to catch the worthless approbation of an inconstant, irrational, and image-doting rabble. The rest whom perhaps ignorance without malice, or some error, less than fatal, hath for the time misled on this side sorcery or obduration may find the grace and good guidance to bethink themselves, and recover.25

John Milton’s political journey may have been a long and uneven one (and remains a subject of contention among Miltonists), but he was now the voice of republican England. The Council also drew on his considerable experience of the practicalities of the book trade. Milton liaised with stationers on the Council’s behalf and arranged publication of official works, as well as contributing his own writings to the political effort. So far, so good, but suddenly, John Milton, the author who had cut his political teeth with numerous unlicensed, illegal publications and defended a free press so eloquently in the (unlicensed and thus illegal) Areopagitica, found himself on the other side of the censorship fence. He now had to enforce the Rump Parliament’s Act of 20 September 1649, which renewed some of the restrictions on the liberty of the press. This was a step backwards for the regime, which had previously taken ‘the calculated risk of allowing full reporting of every stage of the trial in the newsbooks, even though this meant relaying Charles’ sharp retorts against his judges’.26 In the early months of 1649, the Rump had wanted the execution of the King to be public, not private tyrannicide. Now they were keener to control opinion.

By the end of 1649, Milton was a government insider, busier and more productive than he had been at any other stage in his life. That year has been described with some justice as his annus mirabilis. It was the year in which he wrote the Tenure, the first four books of the History, the Observations (a work for the Commonwealth concerning their policy in Ireland) and Eikonoklastes.27 He also prepared numerous Latin letters of State for his masters. All this was achieved as his eyesight continued to decline.

By the end of the year, he and his family were actually living at the heart of government, in Whitehall Palace. On 19 November 1649, a note stipulated that ‘Mr Milton shall have the lodgings that were in the hands of Sir John Hippely in Whitehall for his accommodation as being Secretary to the Council for Foreign Languages.’28 From his house in Scotland Yard, one of the Whitehall courtyards, Mr Milton was on hand to attend the informal, unminuted Council meetings held at the palace, as well as his more formal business for the Commonwealth. Whitehall was not terribly palatial in the seventeenth century. Instead, its tiny courtyards and passageways were reminiscent of a cramped medieval town.29 The palace had been given something of a facelift in the time of Charles I, gaining Inigo Jones’s Banqueting Hall with its Rubens ceiling, but it still remained a sprawling, rambling structure of about 2,000 rooms. As ever, there is nothing to indicate whether and how family life for the Miltons changed with the move. Mary Powell Milton, still only twenty-four years old, would presumably have packed up her clothes, her spices, her plate and her linen, and set up home, bringing her two daughters, now aged three and one, with her.30 Servants of the State had started to bring their families to live with them at Whitehall during the reign of Charles I: Scotland Yard and the Royal Mews had been developed to house ‘every mean courtier’ and his family, much to the dismay of some.

As one would expect, the accommodation for civil servants such as Milton and his family remained far away from what had been the Privy lodgings. Little had changed in the layout and significance of these lodgings now that the monarchy had been abolished. The rooms at Whitehall remained organised according to a system whereby access to each new room signified a further element of trust and acceptance by the ruling power. The names of the rooms had, however, been changed, and in practical terms access had been improved. So, the Queen’s Presence Chamber became the new Council Chamber, and a new route was created to it directly from the river. The various committees that administered the Commonwealth now met in rooms previously used by Royalty. Through the Civil War, Whitehall had been neglected, the gardens suffering in particular. In 1650, they were restored and re-turfed. The palace remained well furnished. The Rump Parliament may have sold off the vast majority of the goods and personal estate of the King but could not resist holding on to about £10,000 of material from Whitehall. By 1651, this figure had risen to £50,000, the goods kept for the use of Parliament. In a move typical of regime change, hundreds of pounds were voted to set up appropriate lodgings for the Council of State and to increase security for Council members.31

As the months went by, the pace of life at Whitehall did not slow. The Council had plenty of uses for their Latin Secretary. Milton was recruited to help with the new government newspaper Mercurius Politicus, launched in June 1650. The newspaper was run by Marcha-mont Nedham, who, only a year earlier, had been arrested for producing a Royalist newspaper, fittingly named Mercurius Pragmaticus. Mercurius Politicus was an attempt to beat the King’s supporters at their own game. Newsbooks and pamphlets had emerged from Charles’s central command at Oxford, and the Royalist newspaper Mercurius Aulicus, which had run from January 1643 to September 1645, had set a new standard of sophistication in propagandist war reporting. Under Nedham, and with a bit of help from Milton, Mercurius Politicus became the predominant newsbook of the 1650s with Nedham, a ‘pioneer in the development of journalism’, using his editorials to disseminate republican theory.32 It was all part of the republic’s attempts to control any internal challenge, epitomised by Parliament’s enforcement of the Engagement of 2 January 1650, in which all men over eighteen had to swear loyalty to a Commonwealth without a King or Lords.

It was harder to inspire or coerce the loyalty of those opponents to republicanism who had fled abroad. In Holland, the exiled English Royalists, led by the son of Charles I, commissioned Claude de Saumaise, one of the great Classical scholars of the period, to write Defensio Regia Pro Carolo I (Defence of the Reign of Charles I). De Saumaise, or Salmasius as he was called in European Latin circles, was, like Milton, known for his remarkable facility with languages at an early age, with Hebrew, Arabic and Coptic among his linguistic armoury. Milton’s new task was to take on Salmasius and his work. The battle between the two men would be one of the most celebrated, not to mention nasty and prolonged, literary and political clashes of the period.

With some cunning, Mercurius Politicus derided Salmasius for months before Milton’s response emerged, creating an audience for the comeback of England’s combatant. At last, Milton’s Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio (The Defence of the English People) was published, on 24 February 1651. Alongside the satire of Salmasius’ grasp of English (the plural of ‘hundred’ is not ‘hundreda’, Milton pointed out gleefully in a prefatory poem), there was no holding back on the personal insults. Salmasius is described as ‘a talkative ass sat upon by a woman’, ‘a eunuch priest, your wife for a husband’, an ‘agent of royal roguery’, a ‘hireling pimp of slavery’, ‘a gallic cock’ and ‘a dung-hill Frenchman’. His wife is a ‘barking bitch’.33 Abusing his French opponent (and his wife) was the easy part. There were many other areas where Milton had to tread more carefully. Salmasius accused the Council of State of tyranny, something Milton was happy to refute, but he also accused the Council of being made up of the ‘wickedest rabble’, since those of noble blood had been excluded. Milton had a problem here, in that he, the son of a scrivener (hardly from the rabble but certainly not from the nobility), had to demonstrate his own natural nobility in the face of this kind of attack. This is one of the reasons that, when writing about himself in the 1650s, Milton was relentless in his assertions of his own gentility, and the nobility of the men he was serving.

Less personal to Milton himself, but equally problematic to the new republic, was Salmasius’ appeal to the traditional interlinking of God, King and Father. In removing the King, the English people were rejecting both God and the family. Milton tackled this head on, bravely taking kingship out of the equation:

But upon my word, you are still in darkness since you do not distinguish a father’s right from a king’s. And when you have called kings fathers of their country, you believe that you have persuaded people at once by this metaphor: that whatever I would admit about a father, I would straightway grant to be true of a king. A father and a king are very different things. A father has begotten us; but a king has not made us, but rather we the king. Nature gave a father to people, the people themselves gave themselves a king; so people do not exist because of a king, but a king exists because of the people.34

For all the confidence, however, Milton’s own anxieties seeped into the Defence. His ideal political models derived from Mediterranean countries, and it appeared genuinely to trouble him whether, for example, the republicanism of Athens or the Senate of Rome could be transplanted to a cold northern country. More importantly, there was a suggestion that the business of the Commonwealth had not been completed: ‘Our form of government is such as our circumstances and schisms permit; it is not the most desirable, but only as good as the stubborn struggles of the wicked citizens allow it to be.’ The crucial issue for the English nation was how to win the peace, having won the war (‘ad ultimum sibi constare, et sua uti victoria sciebant’), above all to know ‘the purpose and reason of winning’.

The hope expressed was that popular liberty had been secured by the army. Again, however, there is a qualification of this apparent support for the people hidden away in the Latin. Milton used a Latin form of ‘popular’ which links the word to the sanior, a fit, appropriate minority. As ever, he was worried by any form of democracy. Government had to be concentrated in the hands of suitable people. Overall, Milton trod carefully, showing some political caution. Charles Stuart in exile had many supporters, and the new Commonwealth needed to rally its own supporters in Europe. Many of the states they were wooing were monarchies, and so the Defence demonstrates the supremacy of law rather than attacking the system of monarchy itself. One Milton scholar goes so far as to say that Milton ‘argues that he is defending the rights of a particular people at a particular time to deal with a particular king, rather than the merits of republicanism’.35 In this reading, there is no republican ideology at work in the Defence, just raw political pragmatism, an attempt to soften the edges of the English political experiment.

If this was the intention, then the plan misfired. While the Defence sold throughout Europe (being Milton’s most frequently reprinted work during his lifetime, with at least ten editions published in the first year alone, including a translation from the original Latin into Dutch), it was also the most viciously attacked. It was publicly burned in cities throughout Europe, most often in the absolutist France of Louis XIV and his Cardinal Mazarin, with the fires lit in Toulouse and Paris in the year of the work’s publication. However cautious the Defence might have been, Milton, as the scholar David Norbrook suggests, still made clear the connection between abuses of Royal power and the very nature of the monarchical office, with its inbuilt tendency to aggrandise the human will.36 In a sign of Milton’s inexorable journey away from establishment respectability, the boy who had played the Elder Brother in the Maske at Ludlow would grow into the man who would write into a copy of the Defence, ‘Liber igni, Author furca, dignissimi’ (The book is most deserving of burning, the author of the gallows).37 The Defence, for good or for evil, established Milton as something of a European intellectual celebrity, described by the Dutch philologist and poet Nicholas Heinsius as extremely well educated, ‘born in a noble position, and brought up in luxury. He is an extremely little chap and in precarious health’,38 or celebrated for his talent by another European intellectual, Isaac Vossius, who argued that the burning of Milton’s Defence would never extirpate his writings since ‘they rather shine out with a certain wonderful increase of lustre by means of those flames.’39

From being one small, if notorious, drop in the ocean of polemical pamphlet writings in the 1640s, Milton’s learning had earned him a voice in government, a voice that would define the new England to a sceptical Europe. It was a voice that he had sought since his return from Italy. In one of his earliest pamphlets on Church Reform, he had outlined his literary plans. An epic and a tragedy were hinted at; both would look back to a time before the Norman Conquest, when the English were free and Christianity was a purer faith, and, above all, both would be ‘doctrinal and exemplary to a nation’.40

His value to the Council was obvious. Just after the publication of the Defence, there was an attempt to remove ‘Mr Milton out of his lodgings in Whitehall’. The pressure was coming from the parliamentary MPs, who wanted Whitehall for themselves, demanding the ‘best conveniences’ and quite happy to move the civil servants out. The Council members stood up for Mr Milton, insisting that he remain in Whitehall, ‘where he is in regard of the employment which he is in to the Council, which necessitates him to reside near the Council’.41

It is unlikely that he had ever been so busy. A fascinating correspondence between him and a visiting ambassador, Herman Mylius, reveals the day-to-day details of his life in government. Milton writes from Westminster, postponing his meeting with Mylius because he has been delayed in a parliamentary meeting. In another letter, he is concerned to get his business done by two in the afternoon, because the Council will be meeting in the evening. There is, of course, an element of diplomatic man-management here, and Milton may well have been buying time. When he does finally respond to Mylius (again claiming a hectic schedule), it happens to be on the same day that the Council approves the motion to consider Mylius’ business, the Oldenburg Case.

Herman Mylius had been sent to London by Count Anthon Gunther of Oldenburg in the summer of 1651 to secure from the English government a safeguard which would give Oldenburg merchants protection from seizure of their goods and vessels by English warships, which were at the time engaged in undeclared naval wars with both France and Portugal. The County of Oldenburg, lying between the United Netherlands and the Hanseatic city of Bremen in the north-west of Germany, had remained neutral during the Thirty Years War and was determined to stay neutral now. Mylius believed that Milton was the man who could ensure that he returned home to Oldenburg with his safeguard.

Mylius needed a bit of managing. His letters are intense creations, diplomatic correspondence at an exalted emotional level. Milton is his ‘dear adornment’, while Herman (quoting the Roman author Horace) is the lover deceived. Mylius signs off that he is ‘yours even in death’ and, in another letter, reminds Milton of ‘yesterday’s promise after our morning embrace’. Mylius even characterises himself as a lover: ‘You must have observed how lovers sicken, who want what they crave at once. But I shall loiter in your love and so die.’ Admittedly, Mylius did have a lot to thank Milton for, or at least that’s how Milton wanted him to see it, hinting that it was he who had pushed the Oldenburg Case through, ‘most eager in your interests and your honour’.42

Meanwhile, through these turbulent years of regime change, economic crisis and diplomatic business, Milton continued to manage his financial resources with exemplary skill, and continued to pay his mother-in-law her widow’s thirds every autumn and spring from the Oxfordshire estate.43 Anne Powell and John Milton were both involved in attempts to establish their rights to the land and property in Forest Hill and Wheatley, and there is much evidence of cooperation between them. The relationship between Anne Powell and her son-in-law had, however, soured by the spring of 1651, as post-war legislation gave to Milton what it took from Anne. When, in March 1651, Milton paid the final fines (two payments of £65) to free the Wheatley estate from sequestration, the Committee in question instructed him to keep all the money from the Powell property rather than hand over a percentage to his mother-in-law. Anne Powell, understandably, petitioned for redress, complaining that she lived in poverty and needed the money ‘to preserve her and her children from starving’. Her youngest child was still only about eleven years old. Her testimony, which survives in the National Archives, was offered in July 1651 and gives a rare glimpse of Milton family life, at least as seen through Anne Powell’s eyes. Anne claims that she cannot raise the issue with her son-in-law, whom she describes as a ‘harsh and choleric man’, because he will take it out on her daughter Mary.44 It is not a pleasant image, of John the bullying husband. At the time she made the claim, John and Mary had just become parents again. On 16 March 1651, Mary Powell Milton gave birth to a baby boy named John, born at 9.30 in the evening at the family’s apartment at Whitehall. By the summer, Mary was pregnant again.

Anne Powell was back in court repeatedly the following year, determined to gain reparation for her losses in the Civil War. Her argument was that Parliament had seized far more than it was entitled to by the Articles of War, including her possessions. The process of litigation was slow and stressful, and cannot have been easy for her, but the tension between her and John seems to have been resolved. Eventually, in May 1654, she did receive a rebate from the state of £192 4s 1d. Others who had supported the Royalist cause were also finding life hard. Thomas Agar, Milton’s brother-in-law, lost his government post in the last years of the Civil War and did not regain it. He had retreated from London to Lincoln by 1650, and it is unclear how he survived over the following years.

John Milton, property owner in London and Oxfordshire and now father to a son, was, in contrast, doing well. The estate at Wheatley yielded only 50s in November 1648 but £10 in October 1650. In 1649, Milton installed a new tenant in the property and, over these years, took in about £280 a year in tithes. Overall, the two years following the execution of Charles I were filled with achievements for Milton. He was exceptionally productive in his writing; successful in his financial dealings; making a political name for himself in England and beyond; the father of a new baby boy; the husband of a wife pregnant with their fourth child. These were, perhaps, the best years of his life.