IN A LETTER TO A FRIEND just over a year later, Milton continued to bear witness to the pain, both psychological and physical, that he had experienced over ten years of weakening sight. He was explicit, as he was nowhere else, about his bodily symptoms (his spleen and his viscera were ‘burdened and shaken with flatulence’) and the progress of his disability:

… while considerable sight still remained, when I would first go to bed and lie on one side or the other, abundant light would dart from my closed eyes; then as sight daily diminished, colours proportionately darker would burst forth with violence and a sort of crash from within.1

Now, in 1654, ‘permanent vapours seem to have settled upon my entire forehead and temples, which press and oppress my eyes with a sort of heavy sleepiness, especially from mealtime to evening.’ At first he was able to see a little, mistily, but now all was ‘pure black, marked as if with extinguished or ashy light’.

Milton wrote in such graphic detail about himself only because his friend, Leonard Philaras, had begged him to describe his symptoms. Philaras knew a doctor who might help. Milton still carried a desperate hope, since a ‘minute quantity of light’ entered his eye when moved in a certain way, ‘as if through a crack’. Perhaps, he wrote, Philaras’s offer of help was an expression of divine purpose. Perhaps his blindness could be cured.

The hope was as faint as the glimmer entering Milton’s eye, and he knew it. The rest of this remarkable letter is dominated by a moving explanation of his acceptance of the incurability of his condition:

Although some glimmer of hope too may radiate from that physician, I prepare and resign myself as if the case were quite incurable; and I often reflect that since many days of darkness are destined to everyone, as the wise man warns, mine thus far, by the signal kindness of Providence, between leisure and study, and the voices and visits of friends, are much more mild than those lethal ones … [I am] capable of seeing, not by [my] eyes alone, but sufficiently by God’s leading and providence. Indeed while He himself looks out for me and provides for me, which He does, and takes me as if by the hand and leads me throughout life, surely, since it has pleased Him, I shall be pleased to grant my eyes a holiday.2

The ‘voices and visits of friends’ were crucial to the process that enabled Milton, a year later, to place all of his troubles firmly in the past: ‘… at that time especially, infirm health, distress over two deaths in my family, and the complete failure of my sight beset me with troubles,’ he could write assuredly in a pamphlet of August 1655.3

Many of Milton’s friends from the mid-1650s were political insiders. Edward Lawrence was, for example, the son of the leader of the Council from early 1654 (as Milton pointed out in the opening line of a sonnet addressed to him), and an MP himself from 1656. Andrew Marvell would have meetings with John Bradshaw and convey the latter’s message of ‘all respect to your person’ to Milton.4 Another friend, both of Milton and Edward Lawrence, was a diplomat from Germany, Henry Oldenburg, who by 1656 had entered Oxford and become tutor to Richard Jones, one of Milton’s ex-pupils in the Aldersgate house.

Through his later forties, friendship was one of the most important themes explored in Milton’s poetry, alongside his own blindness and the political situation. It is both surprising and somewhat cheering to see the return of a language of playful familiarity, with echoes of his poetry of some thirty years earlier. Suddenly, he seems surrounded by young friends, talented, educated, politically engaged men he has met through his teaching or his government work. Not quite a circle, these men often knew each other, and they cared for Milton. Marvell wrote to him, for example, that he was glad that Cyriack Skinner had ‘got near to’ him in London.5 Equally important, letters show Milton sending these friends his latest works, and they in turn offer him support and encouragement. Marvell, developing into one of the great poets of the seventeenth century, was effusive in his praise of his new friend’s prose, writing that he ‘shall now study’ Milton’s latest work ‘even to the getting of it by heart’.6

To these friends, Milton wrote sonnets that, while celebrating the men’s lineage (as he was wont to do), also seem determined to have fun. To Cyriack Skinner, Milton wrote that he intended to ‘drench in mirth’ ‘deep thoughts’; he was going to put aside Euclid and Archimedes, stop worrying about the Swedes and the French. The sonnet was a reminder, partly to Skinner, partly to himself, that it is important to relax: ‘care’ burdens the day, so ‘when God sends a cheerful hour’, enjoy yourself! To Edward Lawrence, an upwardly mobile figure in the political hierarchy and only in his early twenties, Milton wrote a sonnet of friendship expressed in a relaxed, pastoral mode (‘Lawrence of virtuous father’). The weather was terrible, ‘now that the fields are dank, and ways are mire’: how on earth were they going to meet up? As with his earlier Latin poetry, Milton was both imitating a Classical form (this time Horace) and also referring to the actual conditions of his life in rainy England. He looked forward to summer when a

neat repast shall feast us, light and choice,

Of Attic taste, with wine, whence we may rise

To hear the lute well touched, or artful voice

Warble immortal notes and Tuscan air?

He who of those delights can judge, and spare

To interpose them oft, is not unwise.

(ll. 9–12)

Again, Milton was advocating indulgence in the good life, as he did to Skinner. Typically, however, the use of the ambiguous word spare in the penultimate line offers the reader a choice: the wise man either knows how to spare time for pleasures in his busy life, or knows how to indulge himself sparingly. Either way, there is room in life for wine, music and good food, even perhaps for that long-suppressed aspiration, ‘Attic’ salt.

Women are not present in these poems, and there is no reason for them to be so. As ever, it seems that men provided most, if not all, of the emotional life John Milton needed. As with his writings and experiences as a young man, it is impossible to know whether these friendships of his later middle age had a sexual element. Certainly nothing had changed in English society to have made it more acceptable had they done so.

Lack of proof did not stop his enemies, however. The steady stream of hostile responses to the English Commonwealth had continued unabated, and in early 1653, Milton’s simmering feud with Salmasius turned truly nasty. Salmasius claimed in January that Milton had worked as a male prostitute during his time in Italy, ‘selling his buttocks for a few pence’ (Paucis nummis nates prostituisse).7 One of Milton’s European friends (at this period at least), Nicholas Heinsius, leapt to deny the allegation, but the fire had been started. By May 1654, John Bramhall, a Royalist ex-bishop in exile, was claiming that Milton had been sent down from Cambridge for unnatural practices, so shameful that he would kill himself if known.8 Throughout this period, the sexual body and sexual acts were used as metaphors for political engagements and transgressions, and of course Milton himself used this language when attacking his opponents. What is interesting about the attacks on Milton was that he was being accused of having sex with men.

Milton’s response to these and the numerous other attacks at home and abroad was to defend himself and his country. In a letter to his friend Henry Oldenburg, dated 6 July 1654 and written from Westminster, he describes the value of his writings: ‘… what among human endeavours can be nobler or more useful than the protection of liberty?’ He tells Oldenburg that he is continuing to work despite ‘illness’, despite ‘this blindness, which is more oppressive than the whole of old age’ and despite ‘the cries’ of ‘such brawlers’.9

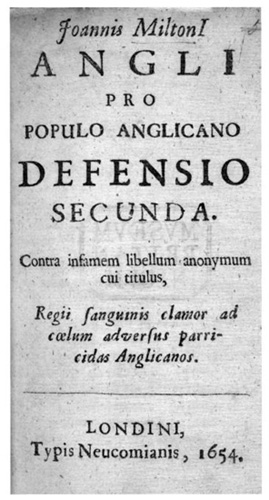

The noble and useful work that ‘John Milton an Englishman’ (as the title page put it) had been working on was a government-commissioned response to an anonymous Royalist publication, Regii sanguinis clamor ad coelum (The Cry of the Royal Blood to Heaven). As Milton himself pointed out, he was still the man for the job. His task in his first Defence had been to ‘defend publicly (if any one ever did) the cause of the people of England, and thus of liberty itself. He had not disappointed since his opponent, Salmasius, had been ‘routed’ and retired, his reputation in shreds. Milton’s Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio Secundo (Second Defence of the English People) continued the work but also gave its author a chance to defend himself against his attackers.

First and foremost, however, the Second Defence was propaganda for the Protectorate and its Protector. The praise for Cromwell is extensive and precise, focusing on his military abilities and his religious conviction. As a soldier, he was ‘above all others the most exercised in the knowledge of himself; he had either destroyed, or reduced to his own control, all enemies within his own breast – vain hopes, fears, desires’. Milton ended the tract by addressing Cromwell directly: ‘… you, who are the greatest and most glorious of our citizens, the director of public counsels, the leader of the bravest of armies, the father of your country’. To the English people, Milton had an equally clear message: Cromwell was ‘your country’s deliverer, the founder of our liberty, and at the same time its protector’.

The Second Defence is a rousing celebration of the new England of liberty in civil life and divine worship, and it refuses to concede an inch to Royalist opponents. The Protectorate is paraded as a model of tolerant government. Milton, responding to the fact that his own works have been burned in Paris, points out that the English could have burned Salmasius’ books in London but simply did not do that kind of thing. With casual insouciance (and a telling conflation of book and author), Milton observes, ‘I find I have also been burned at Toulouse.’ The Second Defence is a resolutely confident work, dominated by Milton’s presentation of himself as the author for this moment when the people of England had thrown off ‘a most debasing thraldom’.

On the other hand, the work is coloured by Milton’s misunderstanding of the authorship of the work he is attacking. He believed that one Alexander More (who had actually only contributed the preface and then taken the work along to the printers) was the author. More made an easy, if inaccurate, target. Yet another of the brilliant European intellectuals of the time (born in France the son of a Scottish clergyman and a French mother), he was a man dogged by controversy, whether over his religious beliefs, not strict enough for some, or his sexual behaviour, too lax for most. Crucially, More was a friend of Salmasius. Indeed, it was in Salmasius’ house, and possibly in his garden shed, that More had inseminated a servant, Elizabeth Guerret, who then claimed that he had promised her marriage, a claim he vigorously denied.

In the Second Defence Milton used every trick in the book to demean, ridicule and dismiss his opponent.10 He fused the sal et lepos of his Latin works with the satiric energy of his early prose tracts, throwing More out of the community of urbane scholars and into the garden shed with his numerous mistresses. Predictably, More responded with Fides publica contra calumnias Joannis Miltoni (A Faithful Statement against the False Accusations of John Milton), exposing inaccuracies in Milton’s tract and condemning the outrageous obscenities in the attack upon him. Milton in his turn replied again, this time with Defensio Pro Se (Defence of Himself).

In the Second Defence, Milton only dropped his abuse of More when he wanted to create space to attack Salmasius, ‘or Salmasia (for of what sex he was, was rendered extremely doubtful, from his being plainly ruled by his wife, alike in matters regarding his reputation, and in his domestic concerns)’. It could all get very silly. Milton created a little Latin poem about herrings, which begins ‘Gaudete scombri…’ (Mackerels rejoice …), and went on to imagine fish dressed in the kit, as it were, of the Salmasius team. As the Victorian Milton scholar Mark Pattison wrote with stern disapproval, the majestic Milton ‘descends from the empyrean throne of contemplation to use the language of the gutter or the fish-market’. It is precisely these qualities that make the work so enjoyable.

Salmasius was, however, dead by the time Milton wrote his Second Defence, and Milton seized on this to score a heartfelt point: ‘I will not impute to him his death as a crime, as he did to me my blindness.’ Milton’s enemies (and even some of his supporters) had argued that his blindness was a punishment, inflicted by God. It was time to fight back: ‘Let us come now to the charges against me. Is there anything in my life of character which he could criticize? Nothing, certainly. What then? He does what no one but a brute and a barbarian would have done – casts up to me my appearance and my blindness.’11 Before tackling his blindness, however, Milton needed to address some other slanders, ranging from his lowly social background to his sexual predilections, from his shortness of height to his lack of ability with a sword. So the reader learns he was born in London, of respectable parents; that his father was a man of integrity, his mother a woman of charity; that he was brought up by his parents for study of literature, languages and philosophy; and that he spent his youth at his father’s country house, ‘completely at leisure’. It is a lovely vision of a man from the leisured, even noble classes: some of it is even true.

Beset by accusations of unchastity, particularly with men, Milton insisted that even in Geneva, ‘where so much licence exists, I lived free and untouched by the slightest sin or reproach’. Accused of being short and ugly, he pointed out that he was no such thing. His complexion was superb, and although he was ‘past forty’ (he was forty-five), ‘there is scarcely any one to whom I do not seem younger by nearly ten years.’ Admittedly, he was not tall, but he was not short, and in any case, even if he were short, it would not be a problem. Accused of cowardice, having not actually taken up arms for the Commonwealth or Protectorate, he pointed out that he had been toiling for his ‘fellow-citizens in another way, with much greater utility, and with no less peril’. In any case, Milton remembered that ‘I was not ignorant of how to handle or unsheathe a sword, nor unpractised in using it every day: girded with my sword, as I generally was, I thought myself equal to anyone, though he was far more sturdy’ He insisted that even ‘at this day, I have the same spirit, the same strength, but not the same eyes. And yet they have as much the appearance of being uninjured, and are as clear and bright, without a cloud, as the eyes of men who see most keenly.’12

This of course is the problem that Milton cannot dismiss, as he all too painfully recognises. He can deny that he is unchaste, ugly and cowardly, but he cannot deny he is blind: “Would it were equally in my power to confute this inhuman adversary on the subject of my blindness! but, it is not.’ The next sentence epitomises Milton’s eloquent courage, both in standing against his enemies and in facing his own predicament: ‘Then, let us bear it. To be blind is not miserable; not to be able to bear blindness, that is miserable.’

This was a hard-won acceptance and achieved in the face of an overwhelmingly negative view and experience of blindness in Milton’s own time, as is evident in his letter to his friend Philaras about his symptoms, in which he thanks him particularly for his kindness to ‘one who could not see’, whose misfortune ‘has made me more respectable to none, more despicable perhaps to many’.

In the writings of the mid-1650s, Milton took on almost all aspects of his disability and transformed their meaning. He refashioned his need for support as a chance to demonstrate exemplary friendship instead of a demeaning dependency on, say, a mentally deficient servant as guide. His friends were such good friends that they would physically guide him; Euripides was brought in to express the ideal: ‘Give your hand to your friend and helper. Throw your arm about my neck, and I will be your guide.’ Milton knew that most blind people could not work. In his case, he pointed out, the government had continued to employ him: they might ‘readily grant me exemption and retirement’, but they had instead maintained his dignity and public office, and paid his salary. Milton knew that blind people were invariably represented as grotesques, and he made clear, therefore, that he was not disfigured by his blindness. (A sonnet to Cyriack Skinner expresses relief that others cannot tell that he is blind.) Milton knew that blindness could be interpreted as a punishment from God, so he suggested that it was the natural consequence of his overzealous studies when a child, when he did not leave his books ‘for my bed before the hour of midnight’. Milton knew what he was up against, and in his writings at this time, he systematically responded to and challenged his enemies’ and his society’s view of his disability.

First, however, he had to deal with his own sense of loss and despair. One of his most famous poems, the sonnet that begins ‘When I consider how my light is spent’, dramatises the ongoing struggle. The ‘light’ of the opening is most obviously his blindness but also could refer to his fragile sense of purpose, and the following lines are confused by tortuous syntax and a puzzling reference to the passing of ‘half my days’. (Milton was at least forty when he wrote the poem, probably nearer fifty, but perhaps he hoped that people really did think he was ten years younger, halfway to his threescore years and ten. Or perhaps he considered the lifespan of his own father, who lived into his mid-eighties.)

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide,

Lodged with me useless …

(ll. 1–4)

The convolution may be the whole point: Milton, considering his uselessness, gets tangled up in complexity. The sonnet itself, as it turns, suggests that the questions are asked ‘fondly’ (i.e., stupidly, innocently). Patience, who responds to these fond questions, is clear in her response: they ‘serve him best’ who bear God’s mild yoke. The poem ends, famously, with Patience’s description of those who serve God:

Thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.

(ll. 12–14)

Milton can, as a blind man, still serve God: his light is not spent. The assurance that ‘they also serve who only stand and wait’ relies for its subtle consolation on both a passive and an active understanding of the verb ‘to stand’. Milton is required both to accept the necessity for stillness and to stand firm.

Another less well-known, but equally touching, sonnet offers a slightly different response to blindness, one which seems more active, certainly more politically engaged. In a poem addressed to his student and friend Cyriack Skinner, Milton recounts three years of complete blindness. His eyes, now ‘idle orbs’, are ‘bereft of light their seeing have forgot’. Again, the psychological struggle is allowed into the poem: the horror of idleness, the grief at the forgetting of the visual world, whether ‘sun or moon or star’, ‘man or woman’. But the fear and bereavement are firmly put aside. Milton does not argue with heaven but vows to ‘bear up and steer / Right onward’:

What supports me dost thou ask?

The conscience, friend, to have lost them overplied

In liberty’s defence, my noble task,

Of which all Europe talks from side to side.

This thought might lead me through the world’s vain mask

Content though blind, had I no better guide.

(ll. 9–14)

Now Milton is arguing that it is in the defence of liberty, the ‘noble task’ ‘of which all Europe talks’, that he has lost his sight. Blindness becomes almost an injury sustained in war.

These kinds of arguments are, in the Second Defence, superseded by a third narrative, and a much more explicitly religious one. John Milton has heard the voice of God. Asked by his God to do more, in the full knowledge that it would hasten his blindness, he has chosen God’s work. His ‘two destinies’ are linked: blindness and duty. Milton writes that he neither believes nor has found ‘that God is angry’. Instead God has shown mercy and paternal goodness towards him. Milton acknowledges that he is classed with ‘the afflicted, with the sorrowful, with the weak’, but he also knows that ‘there is a way, and the Apostle is my authority, through weakness to the greatest strength’: ‘… thus, through this infirmity should I be consummated, perfected.’

Yet the Second Defence, for all these incidents of eloquent confidence in self and nation, has a number of politically jarring moments. Alongside the praise of Cromwell, Milton offers praise of John Bradshaw (sprung, inevitably, from a ‘noble family’), who, as we have seen, was struggling politically at precisely this time. Bradshaw is applauded as a defender of liberty and in very personal terms:

More tireless than any other in counsel and labour for the public good, he is by himself equal to a host. At home he, as much as any man, is hospitable and generous according to his means, the most faithful of friends and the most worthy of trust in every kind of fortune. No man more quickly and freely recognises those who deserve well of him, whoever they may be, nor pursues them with greater kindness.13

Other military and civic leaders who had fallen away from power are also praised in the Second Defence: men such as Gen. Lord Fairfax, admired for his courage, modesty and sanctity of life. The presence of these tributes hints at least at some criticism of Cromwell’s rule, compounded by the suggestion that although the monarchy has been removed, the establishment of true civic and religious liberty is faltering.

Milton felt it necessary to rouse his nation to action, fearful, as he had been as early as the spring of 1649, that the English people were not capable of sustaining liberty. Did they really want to be slaves in their hearts? If so, however hard they fought, they would never succeed in attaining true liberty. Earlier Milton had written that the English needed courage, and not just in battle: ‘every species of fear’ needed to be overcome. Indeed, the English needed more courage than the Romans and Greeks who successfully overcame tyrants, because modern-day tyrants linked their power to their claim to be ‘vicars of Christ’. The lower orders had been ‘stupefied by the wicked arts of priests’, and the civilised world had made their leaders into gods, ‘deifying the pests of the human race for their own destruction’. The English people had to learn to be masters of themselves, remain ‘aloof from factions, hatreds, superstitions, injuries, lusts, and plunders’. If they did not, they would have failed themselves and their nation, and future generations would judge them harshly.

The foundations were soundly laid, the beginnings, in fact more than the beginnings were splendid, but posterity will look in vain, not without a certain distress, for those who were to complete the work, who were to put the pediment in place. It will be a source of grief that to such great undertakings, such great virtues, perseverance was lacking.14

Perseverance would not be wanting if the people listened to John Milton, nor would the praise of future generations. It was Milton who would ‘exhort’ and ‘encourage’, Milton too who would ‘adorn, and celebrate, in praises destined to endure forever, the transcendent deeds, and those who performed them’.

In his Second Defence of the English People Milton offered a dazzling celebration of his own authority, and of the power of the printed word to reach people, cross borders, bring nations together in liberty, to spread ‘the restored culture of citizenship and freedom of life’. Milton, physically trapped by his own blindness in a house in Petty France, could travel the world, conflating book and man as he did so powerfully in Areopagitica:

I imagine myself to have set out upon my travels, and that I behold from on high, tracts beyond the seas, and wide-extended regions; that I behold countenances strange and numberless, and all, in feelings of mind, my closest friends and neighbours … from the columns of Hercules to the farthest borders of India, that throughout this vast expanse, I am bringing back, bringing home to every nation, liberty, so long driven out, so long an exile.15

It is a tremendous performance. Only after a few moments does the reader realise that Milton has also defended the political status quo (Cromwell as Lord Protector) without making clear exactly how Cromwell was creating the land of civic and religious liberty to which the Second Defence aspired.

In reality, Cromwell’s government was lurching towards dictatorship. The internal threat from Royalists was increasingly insignificant. A Royalist rising in Wiltshire in March 1655 was easily crushed, and Cromwell’s Secretary to the Council, John Thurloe, had now become an astute chief of intelligence, even infiltrating Charles Stuart’s entourage in exile. Any opposition to Cromwell was coming from what had been his own side. Bradshaw and his allies, now ‘Common-wealthmen’, might criticise the formation of the Protectorate, but their voices carried no political or military weight. MPs in the shortlived First Protectorate Parliament were forced to sign a Recognition of the new constitution (the Instrument of Government) which legitimised Cromwell’s rule, or resign. The same year, Cromwell tightened up the licensing system, focusing on the dissemination of news.16 He moved to suppress all newspapers except official publications like Mercurius Politicus.

John Milton’s gory sonnet ‘On the late Massacre in Piedmont’, written during this period, suggests, at first sight, that he was still very much Cromwell’s man, despite these political moves. The poem was a direct product of Milton’s involvement with the construction of the diplomatic letters that were written in response to this massacre. Piedmont (on the borders of France and Italy) was the home of the Vaudois community, which had been excommunicated by the Church as early as 1215, and whose members were thus viewed as natural allies to the Protestant English, who had left the Catholic Church three hundred years or so earlier. Since 1561, the religion and lives of the quasi-Protestant Vaudois had been protected by a treaty with the Duke of Savoy, but in 1655 the current duke sought to expel them from his territories. The Vaudois attempted to escape to the mountains but were pursued. They were either massacred or died in the snow. The number of dead was estimated by the Vaudois themselves at 1,712. Cromwell was personally interested in their cause, and Milton was instructed to write letters of protest to various European leaders, on 25 May, and to write (or most likely translate) an address to be delivered to the Duke of Savoy by Sir Samuel Morland, Cromwell’s special ambassador. The day itself was proclaimed ‘a day of solemn fasting and humiliation’ for all of England, and parishes were directed to take up a special collection to assist the survivors. In all, an impressive £38,000 was raised, including £2,000 from Cromwell himself.

This was the moment at which Milton wrote his poem. The opening five lines take no prisoners, commanding God with autocratic verbs to wreak vengeance (‘Avenge O Lord thy slaughtered saints’) and to register the crime: ‘Forget not: in thy book record their groans.’ The ‘book’ here is the one mentioned in the Book of Revelation 5:1 (‘I saw in the right hand of him that sat on the throne a book’), Milton invoking the most apocalyptic text in the New Testament. The poem continues with a graphic description of the massacre: the soldiers ‘rolled / Mother with infant down the rocks’. He was not being gratuitous. One account of the massacre included three different women who were hurled down a precipice with their children. In one case, incredibly, the baby survived. The blood of the innocent will, the sonnet envisions, be sown throughout ‘the Italian fields’ controlled by the ‘triple Tyrant’, an allusion to the Pope’s three-tiered crown. Milton combines the legend of the dragon’s teeth and the biblical parable of the sower to create an image of Reformed religion springing up at the heart of Roman Catholicism. He had cut his Protestant teeth on opposition to Catholicism and then Laudianism, so it was entirely consistent to espouse this view in the 1650s. It helped, of course, that Milton was echoing the language and beliefs of his leader, Cromwell.

Millenarianism could, however, threaten as well as support Cromwell’s rule. On 7 January 1654, a Fifth Monarchist called Anna Trapnel was ‘seized upon by the Lord’ in a room in Whitehall, and began praying and singing. Her friends took her to a room in a nearby inn where she stayed for twelve days, neither eating nor drinking for the first five, then drinking some small beer, and eating a little toast, once a day. Lying rigid in bed, she alternated prose prayers and verse songs in ballad or common hymn metre in sessions lasting from two to five hours.17

Trapnel was visited at the inn by at least eight members of the disbanded Barebones Parliament, as well as many hundreds who did ‘daily come to see and hear’. She was saying some very strange things, but embedded in her rambling words were apocalyptic threats:

Write how that Protectors shall go

And into graves there lie;

Let pens make known what is said, that

They shall expire and die.18

On the last day of her prophesying, the Council of State, severely worried, published an ordinance that made it treasonable ‘to compass or imagine the death of the Lord Protector’ or to declare his government tyrannical or illegitimate.19 Marchamont Nedham, editor of Mercurius Politicus and a man with his finger on the pulse of print culture, remained concerned. He wrote to Cromwell warning the Protector that there were plans to print Trapnel’s ‘discourses and hymns’ and to send her out into the country to proclaim them. Trapnel was doing a ‘world of mischief in London. Her prophecies might be nonsense, but they might influence ‘the vulgar’. Nedham promised Cromwell that he would move swiftly and seize copies of the prophecies, and show them to him: ‘… they would make 14 or 15 sheets in print.’20 Eventually, Trapnel was sent to Bridewell and imprisoned in a cell infested with sewage and rats.21

Anna Trapnel’s fate epitomised the stranglehold that Cromwell had on rule at home, if also suggesting some of the tensions generated by that rule, most obviously that between his religious radicalism and his social and political conservatism. The latter ensured that viewpoints such as the Levellers’ would remain intolerable, and that Cromwell’s view of the people and their power would remain politically conservative. His confidence and pragmatism were fuelled not by political ideology but by his sense that he was doing God’s work.

In the following year, news came from abroad that made this deeply religious man question his own actions, precipitating yet further political change. When the Protectorate’s forces were defeated in the Caribbean, Cromwell took it as a sign of God’s displeasure. He became depressed and upset, and then fuelled by renewed religious zeal. The Reformation needed to progress more swiftly; the suppression of vice and the encouragement of virtue, which were the very purposes of magistracy, needed to be attended to, and urgently.22 This belief precipitated his next step, the establishment of open military government led by the Major-Generals, who would enforce the godly Reformation throughout the country, something that successive parliaments had been unable to deliver. (The Major-Generals also enforced a ‘decimation’ tax whereby 10 per cent of the value of the estates of known Royalists worth over £100 per annum in land, and £1,500 per annum in goods, came to the government. It all helped to pay Cromwell’s armies and avoided taxing the rest of the predominantly neutral if not loyal gentry.) Cromwell ordered his Major-Generals to put into effect the ‘Laws against Drunkenness, Blasphemy, and taking the name of God in vain, by swearing and cursing, Plays and interludes, and prophaning of the Lord’s day, and such like wickedness and abominations’.23 They were to control ale houses, gaming houses and brothels.

These were the unprecedented conditions in which there was talk of readmitting the Jews, expelled back in 1290, to England. Radical millenarians knew that one condition for the Second Coming of Christ was the conversion of the Jews: it would help if there were Jews to convert. (There would also be some useful economic side-effects, the Jewish community being thought to offer the prospect of business acumen and capital unrivalled in the period.)24 Any readmission would be an astonishing step, on the surface at least challenging the entrenched anti-Semitism of English Christian culture.25 Even for those Christians who wanted the Jews to return, the desire caused anxiety since it went so profoundly against the grain of their beliefs and practices. A conference was convened by the Council of State to discuss the issues, and the leader of the Dutch Jewish community, Menasseh ben Israel, travelled to England to discuss the prospect of readmission.26 In the end, nothing official was decided; no formal readmission occurred. Both the original suggestion, and the inability to come to a decision, signalled the crisis in government.

Cromwell himself was unable to see a way forward. Tellingly, his strength and his vulnerability lay in his religion, not definable by denomination (and in this similar to Milton’s) but nevertheless of vital importance to him. His belief in ‘remarkable providences’ meant that when things were going well, he knew God was with him. Back in 1648 this attitude had inspired and justified military victory. But in the mid-1650s, with things going wrong, whether a military defeat, or the loss of his beloved daughter Elizabeth to cancer, or the impasse over the readmission of the Jews, God’s purposes were less clear.

In March 1656 Cromwell appeared utterly perplexed as to the way forward for the country, or at least he announced that he was, publishing a fast-day declaration announcing that he awaited ‘a conviction’ enabling him to see the way forward, and the recovery of God’s ‘blessed presence’. He appeared to be offering an invitation to politicians and religious figures to offer their counsel. Henry Vane, for one, emerged from political retirement to urge representative government, where the ‘whole body of the good People’ should exercise their ‘right of natural sovereignty’. Another response came from James Harrington, the leading English republican political theorist, who published The Commonwealth of Oceana in 1656: ‘… his proposed republic entailed regular elections for all public offices and secret ballots among a citizenry of independent gentlemen.’ Harrington’s republicanism would be profoundly influential on the constitutions of the early American colonies, and on the rebels of 1776.27

But in 1656 Cromwell was not really listening to anyone but God. Instead, arguing (as is so often done at these moments in history) that the English people were under threat from their ‘great enemy’ the Spaniard, he assumed absolute power. He was starting to look very much like a King. Nedham’s newspaper, Mercurius Politicus, reported obsequiously on something akin to a royal wedding: ‘… yesterday afternoon his Highness went to Hampton Court, and this day the most illustrous Lady, the Lady Mary Cromwell, third daughter of his Highness the Lord Protector, was there married to the most noble Lord, the Lord Falconbridge, in the presence of their Highnesses and many noble persons.’28 Whitehall and Hampton Court became in effect the courts of the Protector, still decorated with the remnants of Royal collections, still serving very similar functions. A historian of dress notes the phenomenon whereby official portraits of the 1650s ‘frequently copied Van Dyck’s paintings of the courtly regime, simply substituting new parliamentary heads for old royalist ones. Thus despite the disruptions of political and social life, the visual appearance of the elite remained unbroken until the 1660s’.29 The evidence of the portraits and the palaces was only one aspect of Cromwell’s rule. The same religious faith that brought him to such power and glory also ensured that Cromwell would not be King. When offered the title of monarch he said no, because he would not ‘seek to set up that that providence hath destroyed and laid in the dust’.30

This was the highly charged political world in which John Milton continued to work, the volatile government he continued to serve. There was still no retreat from public life. He continued with many of his duties, producing a steady stream of correspondence, whether on the subject of foreign shipping, the political situation in Algiers or introducing the new English Resident to France (a process that took many, many months). As the Protectorate moved to ban or even to burn books of ‘prophane and obscene matter’ (a book ordered to be burned in April 1656, a poetic miscellany full of sportive wit or, as the Council saw it, ‘scandalous, lascivious, scurrilous, and prophane matter’, was actually edited by Milton’s own nephew, John Phillips), the ideals of Areopagitica seemed a far-off dream.

For most people, however, Areopagitica was long forgotten. John Milton remained in the bookstalls but most notably as a defender of the Commonwealth and Protectorate, most notoriously as the defender of divorce and, in some quarters, as a poet. In the heart of government, Westminster, Milton, Latin Secretary to the Council, remained actively involved in sustaining the international prestige of his country and its leaders. Day by day he composed ‘some of the soaring Latin letters with which Cromwell hoped to rally the Protestant powers of Europe’, and for Milton scholar Stephen Fallon, much of the ardour of these letters is Milton’s own, as in the following plea to the Dutch on behalf of the Vaudois:

You have already been informed of the Duke of Savoy’s Edict, set forth against his subjects inhabiting the valleys at the feet of the Alps, ancient professors of the orthodox faith; by which Edict they are commanded to abandon their native habitations … and with what cruelty the authority of this Edict has raged against a needy and harmless people, many being slain by the soldiers, the rest plundered and driven from their houses together with their wives and children, to combat cold and hunger among desert mountains, and perpetual snow.31

The letter to the Dutch was one of a series, using similar rhetoric but adapted for each recipient, ranging from the Evangelical Cities of Switzerland and the Most Serene Prince of Transylvania (likely supporters) to the King of France and Cardinal Mazarin (likely opponents). The most crucial was the one to the Duke of Savoy himself:

Partem tamen exercitus vestri in eos impetum fecisse multos crudelissime trucidasse, alios vinculis mandasse, reliquos in deserta loca montesque nivibus coopertos expulisse, ubi familiarum aliquot centuriae, eo loci rediguntur ut sit metuendum ne frigore & fame, brevi sint misere omnes periturae.

(25 May 1655, from Our Hall at Westminster)

A part of your army fell upon ’em, most cruelly slew several, put others in chains, and compelled the rest to fly into desert places and to the mountains covered with snow, where some hundreds of families are reduced to such distress, that ’tis greatly to be feared, they will in a short time all miserably perish through cold and hunger.32

Did Milton relish the opportunity to give voice to Cromwell’s vision, which, put most generously, involved a passionate commitment to Protestant unity, urged as a holy cause?33 He was certainly complicit with the defence of these policies, and indeed the defence of the more pragmatic moments in Cromwell’s foreign policy, when England made alliances with Catholic powers and waged war on her fellow-Protestants.

Political pragmatism, if that is the best way to describe Milton’s activities at this time, was a common feature of life under Cromwell, is indeed under any system of government. Having said that, Milton did not need to work for Cromwell’s government: it seems he chose to do so. He was still living in Petty France, presumably with his daughters, Anne, Mary and Deborah, who celebrated their ninth, seventh and third birthdays respectively in 1655. Milton himself would be forty-seven in the December of that year. He had time to turn to his private studies, starting work on a Latin and then a Greek dictionary. In May 1656, he wrote fairly happily to friends about his time at Cambridge, about people they knew at Oxford, about mutual friends travelling between England and the continent. Presumably he had servants who kept house for him, and probably a woman who cared for the girls. Money was not a problem at this time, although it seems to have been for Milton’s mother-in-law, who sued again for war reparations in January 1656, again without success. Other legal cases involved Milton, predominantly concerning the estate in Oxfordshire, but there was little threat either to his ownership of the land or to his income from it. As he acknowledged in the Second Defence, he was permitted a substitute for the work he could no longer do, with a concomitant reduction in salary to £150, but this was guaranteed as a pension for life. It is probable, given his financial astuteness, that he did not need this £150.

Perhaps his continued service to the government reflected his belief that he was in a good position to influence events, able to offer guarded criticisms of Cromwell carefully couched in the form of comparisons or advice from his position as political insider. There is a prevailing sense in Milton’s writing that Cromwell knew how to win battles but not how to govern. Even in the Piedmont sonnet, which seems so bloodthirsty and apocalyptic, the lesson for future generations (in Milton’s eyes at least) is to be more wary, to flee before your enemy gets you: ‘who having learnt thy way / Early may fly the Babylonian woe.’ In contrast, Cromwell was not someone to advocate pre-emptive flight. Similarly, in the Second Defence the praise of Bradshaw’s hospitality and assiduity in Council stands in contrast to Cromwell’s ruthless military energy. Also Milton praises Robert Overton, a man interrogated and imprisoned by Cromwell shortly after the work’s publication, and a figure who became synonymous with protest. Overton was a hero to Milton, ‘who for many years [had] been linked with a more than fraternal harmony, by reason of the likeness of our tastes and the sweetness of your disposition’.34 These were not the kind of terms John Milton used of Oliver Cromwell.

Meanwhile, others who were wont to express oblique disapproval of Cromwell, such as Andrew Marvell, elected MP for his home constituency of Hull in 1659, nevertheless took posts in his government. So did John Dryden, another famous poet. Unlike Dryden, and to some extent Marvell, Milton did not subsequently turn his back on the republican ideal. Milton’s support of Cromwell’s regime was not mere political time-serving. Even in the mid-1650s, he believed that the civic and religious liberties he desired were most likely to be delivered by Cromwell, whether through the form of Council, Parliament or the rule of the Major-Generals. Above all, Cromwell was committed to religious toleration and to the separation of Church and State. These were the two fundamentals for John Milton.

In 1656, he had the opportunity to enact, in a small way, one of his ideals. He had argued through the 1640s that the ministers of the Church had no right to involve themselves in the nuptial contract. So, when on 12 November John married Mistress Katherine Woodcock of the parish of Aldermanbury, spinster, in a civil ceremony presided over by a Justice of the Peace, with the Church no longer involved at any stage in the proceedings, his marriage was conducted according to his religious and political ideal.

The new Mrs Milton came from a relatively modest background. Katherine’s father, killed in the wars in Scotland, had been a seller of leather and, occasionally, of books before going for a soldier. He had demonstrated such ‘improvidence’ in financial matters that when Katherine’s mother, Elizabeth, was bequeathed £10 by her stepmother it was stipulated that the money should be ‘paid unto her and not to her husband upon her own acquittance’. This prudent woman also willed that her executors ‘be kind and loving to my said daughter Elizabeth Woodcock, so that she may have as free entertainment in my now dwelling house as now and hitherto she hath had … And I do give and bequeath unto my grandchild Katherine Woodcock a feather-bed and bolster and also a little chest with all things to be found therein, the key of which chest I have already delivered to her’.35 Presumably, Katherine brought this furniture to the house in Petty France on her marriage to John.36

John Milton did not need a wealthy bride. He still had spare cash to buy books from Europe, and continued to acquire property and make loans. But he had three daughters to care for. A wife might be helpful in the raising of daughters; remarriage was nevertheless a serious step. When Oliver Heywood, he who had mourned his wife so much and congratulated himself on finding the ideal maid to help care for his young children, considered marrying again, it provoked much soul-searching: ‘… now at last I am thinking of changing my condition, and have been spending part of this day in solemn fasting and prayer to mourn for my sins and beg mercy’ The solemn fasting and prayer reassured him, and he reported happily that he was ‘abundantly satisfied in my gracious yoke-fellow’.37 Heywood was concerned in part because his first marriage had been so happy, but commentators also pointed out that those who had been unhappily married could have hopelessly high expectations of a second wife or husband. They might even seek ‘jollity, and a braver and fuller life, then formerly they were content with’.38 And, of course, sex. Despite, or perhaps because of, anxieties about the carnality or wastefulness of sexual acts, couples were increasingly encouraged to ‘mutually delight’ in each other. This advice was partly based on attitudes towards women’s health. ‘The use of venery is exceeding wholesome,’ advised a book called The Woman’s Doctor in 1658, so much so that widows who were not having sex were encouraged to ejaculate seed (as the female orgasm was understood to do) with the aid of ‘a skilful Midwife and a convenient ointment’. More important, however, sexual pleasure was viewed as essential to conception’.39

While it is pleasant to think that Milton did experience ‘jollity and a braver and fuller life’, and while it is certain that he did have sex with his new wife, he could just as easily have had few or no expectations of personal happiness, or indeed been disappointed if the fuller life he hoped for did not materialise. It is impossible to know since once again the personal documents simply do not exist.

What is known is that Katherine was twenty years her new husband’s junior, twenty-eight to John’s forty-eight. This is no surprise. Older men of Milton’s generation were far more likely to remarry than older women (90 per cent of men over sixty were married, only 25 per cent of women of that age) and two-thirds of these ‘elderly’ married men had wives who were more than ten years younger than themselves. The strategy was all part of a determination on the part of widowers to guard against destitution or neglect. Their young and active wives would provide some protection.

John Milton’s young and active second wife took on the responsibility of caring not only for an older, disabled husband but also for his three daughters. There is no indication of the girls’ response to their new mother, although one John Ward, making notes about Milton, wrote that she was ‘very indulgent to her children in law’, as stepchildren were referred to at the time.40 Within only three months of her marriage, Katherine was pregnant. On 19 October 1657, John Milton’s fifth child, and his new wife’s first, was born, a baby girl named Katherine for her mother.

Little else is known about Katherine Woodcock Milton. Nevertheless, for some reason, this second marriage is invariably represented, even by the most hard-headed of biographers, as an idyll, a rare period of happiness in Milton’s emotional life. There is, however, absolutely no evidence that this was the case. That Milton did not complete any translation work for the government between January and July of 1657 may indicate his focus on domestic life, but it may also have been a product of the acute political uncertainties at the time. During this period, Cromwell abandoned the constitution that had, to some extent, legitimised and provided a curb on his powers, the Instrument of Government, and the reign of the Major-Generals was also halted. Rejecting the title of King in April, by June Cromwell was restored as Lord Protector and granted £1.3 million to run the country.

Whatever its nature, the new Milton family unit would be as shortlived as Cromwell’s experiments in government. Just over three months after giving birth to baby Katherine, Katherine Woodcock Milton died, probably of tuberculosis. She was only one month short of her thirtieth birthday. Anne Milton was twelve, Mary nine, Deborah five: Katherine Woodcock Milton had been a mother to the girls for only fourteen months, and now she left behind a new baby girl as well. Baby Katherine would not live much longer than her mother, dying before she reached five months old. If Milton’s strategy had been to provide for his old age and disability, then things had not worked out as planned. If there had been a sincere commitment to Katherine, as seems possible, the damage was more long-lasting. John Milton had been emotionally courageous enough to marry again, but he had now lost the one woman he had loved, and her only child.

He certainly gave Katherine a good funeral, providing a very public statement of his family’s status. She was buried in St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, the parliamentarians’ church. The bill for the ceremony survives, because this was a State funeral, if on a very small scale:

Work done for the funeral of Secretary Milton his wife her name Woodcock

Item for eight Taffaty escouti [taffata escutcheons] |

02–13–4 |

Item for one dozen Buck escou |

01–10–00 |

Item for a pall |

01–00–00 |

|

05-03-441 |

This was a fine funeral for Secretary Milton’s wife.42 The note of expenses carried a parted shield, with the Milton arms (the spread eagle, originally the sign over the Milton family business) on one side and the Woodcock arms on the other. The spread eagle proclaimed Milton a gentleman. A story went that ‘when Mr Milton buried his wife he had the coffin shut down with 12 several keys, and that he gave the keys to 12 several friends, and desired the coffin might not be open’d till they all met together’. True or not, the story speaks to the apocalyptic flavour of the Cromwellian establishment.43

The funeral is yet another piece of evidence that Milton was more than a mere cog in the government, and it also demonstrates his desire to celebrate his wife’s life publicly.44 One of Milton’s most expressive and powerful poems offers a glimpse of the emotional, spiritual and psychological impact of a wife’s death. In this sonnet, all the grief of the widower emerges. He dreams of his dead wife. In his ‘fancied sight’, she appears to him; she shows him that she is with God, redeemed, out of pain. He believes that he will have ‘full sight of her in heaven without restraint’. Surely this is a consolation? But in a devastating final line, Milton writes, ‘I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night.’

Yet, tantalisingly, the evidence resists any certain connection between this poem and Katherine. It may well have been composed at the death of Mary Powell Milton. Katherine did not die in childbirth (the wife in the poem does), whereas Mary did. The belief, rehearsed in almost all modern biographies, that Katherine was John’s true love, and Mary his merely functional wife, forces Katherine into the poem.

None of this matters. The sonnet is a quite brilliant evocation of grief. Here, at last, the Classical allusions do not merely lend elegance or distance to the poem: they generate an emotional charge. The dead woman is both like Alcestis, who in Euripides’ play gave her life for her husband’s, and not like her: Alcestis was brought back from the grave by Hercules; Milton’s wife remains lost. Milton is both like Odysseus, who sought to clasp his mother’s shadow, and not like him, because in Milton’s poem there is only one doomed attempt to clasp his wife, while his Classical sources allow Odysseus the luxury of three. Above all, here, at last, Milton uses a twist at the end of a poem to intensify the emotion rather than to diffuse or complicate the reader’s experience. In simple monosyllables the agony of bereavement is expressed, all the more starkly in contrast with the convoluted syntax of the previous thirteen lines. ‘I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night’: the pain of his bereavement and the experience of blindness are fused in that one desolate line. Consolation is fantasy. Consciousness is darkness.