Dönitz used to round off his conferences with his officers with a free discussion. A favourite topic was the relationship of the Wehrmacht to the SS. Dönitz, opposed to the spreading or intensification of tensions because it tended to undermine confidence in the leadership and harm the fighting morale of the forces, would sidestep the question with: ‘So what? Reichs-Heinrich and I are the best of friends.’

What was this friendship like in reality? In the eight months I was Dönitz’s adjutant there was only a single non-official meeting between the pair of them, a dinner at FHQ in October 1944. There was no obvious good humour. On another occasion in February 1945, this time on official business, Dönitz went to see Himmler, who was also Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Vistula, at his HQ in order to discuss operational and armaments question for 1. Marine-Infanterie Division, which had been incorporated into the Army Group. These were their only meetings in the decisive six months of the war from October 1944 to April 1945. They exchanged only passing courtesies on meeting at a few situation conferences at FHQ, which both attended only irregularly. There were virtually no areas of dispute between them and each had respect for the orderly manner in which the other ran his official business, but the word ‘friendship’ is hardly apposite, it was much more a correct and polite relationship based on clear divisions of command. This relationship clouded over as the collapse began and led finally to separation. Later they were compelled to meet more frequently. Dönitz, as regional head, and Himmler, as Chief of Police and the Ersatzheer, and also possibly predestined to succeed the Führer, had both gone North. On 26 April at Schwerin they discussed the defence of the North, the maintenance of order and the refugee transports. On 27 April they met by chance at the OKW situation conference at Rheinsberg where Himmler played the Crown Prince, and on the afternoon of the 30th at the Lübeck police barracks where Himmler denied he had ever offered to capitulate as alleged by enemy radio stations on the 28th.

Especially dramatic was the meeting on the night of 30 April when Dönitz asked Himmler to come to his HQ, where he wanted to reveal his own appointment as Hitler’s successor. Uncertain as to how this announcement would be received, and warned by Gauleiter Wegener, who was better informed on the political infighting, the Grossadmiral took special precautions. He reinforced the barracks guard with reliable U-boat men, and it was everything I could do to convince these enterprising submariners, sworn to loyalty to Dönitz, to exercise restraint and keep themselves as inconspicuous as possible so as not to create from the outset an atmosphere redolent with suspicion. Then I received the Reichsfiihrer, invited his escort into the mess, and accompanied him myself to meet the new head of state. The meeting was held in private and was recorded in a memorandum by Dönitz later in these terms:

I spoke with Himmler in my room alone. I thought it was better to place my Browning within reach on my desk underneath a sheaf of papers. I handed him the telegram to read. He went pale. He thought about it. Then he rose and congratulated me. He said, ‘Let me be second man in the state’. I declined. We then had a conversation lasting about an hour in which I discussed with him my intentions and reasons for as unpolitical a government as possible if such a thing could be managed, while he insisted on the great advantages of my having him at my side. He surprised me with his belief that he had many admirers abroad. He left between 0200 and 0300 hrs knowing that I would not use him in a senior position. On the other hand I could not cut him loose completely because he controlled the police. Mind you, I knew nothing at that time of the concentration camp atrocities and murder of the Jews.

The Reichsführer left with his entourage at around 0230 hrs. The situation had been explained. Himmler came to our HQ on a few more occasions, for conferences on the occupied territories on 3 and 4 May. His position deteriorated rapidly. At 1700 hrs on 6 May Dönitz received him for the last time in order to relieve him of all his offices. The grounds for this development were as follows:

1. Dönitz considered Himmler to be political dead weight. Dönitz was convinced that while Himmler thought of himself as absolutely indispensable in the present situation, having him as a negotiating partner was out of the question. To have given him some office as a sop would also have imposed a heavy burden on Dönitz’s ‘Unpolitical Cabinet’ and the course on which he was set.

2. In the days of the collapse, Himmler proved to be a pure fantasist. His statements were the best proof of this. He considered himself a suitable conversational partner and negotiator with Eisenhower and Montgomery. Why, these gentlemen were certainly only waiting for the chance to talk with him. As the ‘factor for order in Central Europe’ he and the SS were indispensable. This would bring the clash between East and West to the boil so quickly that he and the SS would tip the scales within three months. On the question of the capitulation, on 4 May he considered Norway and Bohemia as ‘bargaining chips’ representing valuable and cashable assets in any negotiations. In captivity, after thinking about reports from Himmler’s circle I believe it is possible that his delusion about the West being prepared to negotiate with him arose not only from his fantasies but also from his own schemes for capitulation, in which he had apparendy even toyed with the idea of a coup to unseat Hitler and had made some preparations along those lines.

3. In the very clear denial of 30 April at Lübeck, the Grossadmiral learned on 3 May from Himmler’s own mouth that he had indeed extended peace feelers through Sweden. Dönitz was very blunt on the matter: ‘Whoever lies to me once will do so often’ and even stronger, ‘Whoever betrays you once will do it a second time’.

Thus on 6 May Himmler disappeared from our sight, ever the optimist. ‘He felt absolutely safe against discovery and would await rapid developments from concealment.’ That same day, Schwerin von Krosigk told him in no uncertain terms about the probable and actual developments in the situation which would arise later, and made clear that the day could come when the leaders of the Third Reich might have to answer for what their subordinates had done, and to rebut the terrible accusations being made by enemy propaganda. This perceptive warning was ignored by Himmler not only at the expense of his subordinates and the organisation under his command, but also that of historical truth. Later Dönitz regretted releasing Himmler. Under pressure at Nuremberg, he stated that he would have arrested Himmler on the day he left had he known then about the massacres and the conditions in the concentration camps.

This raises the question: Did Dönitz really know nothing of it? The statements that have to be made here go beyond the realm of the personal. They embrace the overwhelming majority of the German people and the Wehrmacht. We know from the Nuremberg Trials, especially the statements by SS-Judge Dr Morgen, of the refined and even ingenious manner in which the true circumstances and intentions were hidden. Rumours that occasionally reached Dönitz, the source of which being mostly identified as the foreign news agencies, were disbelieved. The few concrete allegations in Germany were proved fictional. An example here was the myth of U-boat commanders Prien and Schulze being in a concentration camp. Schulze disproved the report himself when he heard it repeated by Dönitz’s staff by turning up in person to argue it was not true. This of course provoked great merriment. Prien perished in the North Atlantic in March 1941 during an anti-convoy operation. False propaganda about the sea war and other theatres caused the majority of the German people to lose faith in reports emanating from foreign news agencies to which they had initially been receptive. Thus it was not the ban on listening to foreign news broadcasts that robbed the enemy news agencies of their potency but their puerile and transparent lying, which made them an easy prey for German counter-propaganda.

Obviously Dönitz knew that the inmates of concentration camps were not treated with kid gloves, while Himmler was adroit in letting the world know that he would take draconian measures against camp staff as soon as he was made aware of excesses. The court martial of two camp commandants which Himmler instigated personally in 1944, the severe sentences and subsequent executions pacified the doubters by showing that even here an iron broom swept clean when it was necessary. In a case which Dönitz investigated in connection with the 20 July Plot, he received a satisfactory response and a quick resolution of the case.

During the capitulation, reports on concentration camp atrocities increased substantially. Generaladmiral von Friedeburg brought from Eisenhower’s HQ illustrated material and newspapers with reports and photos. Some people thought they had seen a number of these pictures before at the time of Katyn. Others thought the pose of the victims and the damage to the surroundings hinted at bombing or artillery as the cause. But the remainder were very worrying. Many of the atrocities described in the reports might have been attributable to the chaotic circumstances during the collapse. The withdrawals westwards of whole camps ordered in many places, and above all the total disruption to the highways which made organised supply and the distribution of food impossible, had undoubtedly been devastating in their effects. These were things that the German people and especially millions of refugees had experienced equally.

A definite case came to light at Flensburg when a prison ship with concentration camp inmates arrived from the East. As were all vessels of the time, this steamer was overloaded and there was a food shortage aboard. The situation had become rapidly catastrophic when the ship was held up outside the port by an enemy minefield. When she finally berthed the crew and guards were found to have decamped and the harbour commander was faced with a vessel in the most appalling condition. His report was horrific. Dönitz ordered personally immediate relief supplies and medical care, which was expedited by Kapitän zur See Lüth as senior coastal station officer.

This occurrence resulted in more credence being given to enemy reports. In the knowledge that atrocities had actually been committed in this case, which were alien to the German people and Wehrmacht, it was considered a matter of honour to investigate and deal with the crime. At the suggestion of Schwerin von Krosigk, on 15 May Dönitz issued an ordinance in which the Reich Court was declared the competent authority for the investigation and prosecution of all excesses in the concentration camps. During a conference with Ambassador Murphy on another matter, Dönitz requested him to refer the ordinance to Eisenhower with the request that he enable the German authorities to exercise this function. Murphy agreed to do so, but we never received an answer.

I have no doubt whatever that such a proceeding carried out with German thoroughness, rigour and objectivity, those convicted receiving the severest punishment, would have been all the more impressive for the German people than the mixture of fact and fiction served up by press and radio. I therefore consider it regrettable both from the German and Allied points of view that the attempt by the Dönitz Government to include German judges in the prosecution of concentration camp activities was not taken up.

Karl Dönitz joined the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) as a cadet in 1910, was commissioned in 1913 and rose rapidly through the ranks. In January 1942 Hitler appointed him Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine. He succeeded Hitler as head of state after the Führer committed suicide in April 1945.

Grossadmiral Dönitz (centre) with Mussolini and Hitler in 1943. In February of that year Dönitz had flown to Rome to ask the Italian dictator for the use of a number of Italian submarines as transport vessels to support German U-boat operations in Far Eastern waters, where supply was a serious problem.

Dönitz at the funeral of his predecessor as Commander-in-Chief, Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, in 1960. The two men had often disagreed – significantly Raeder had opposed Dönitz’s ‘wolf pack’ U-boat tactics.

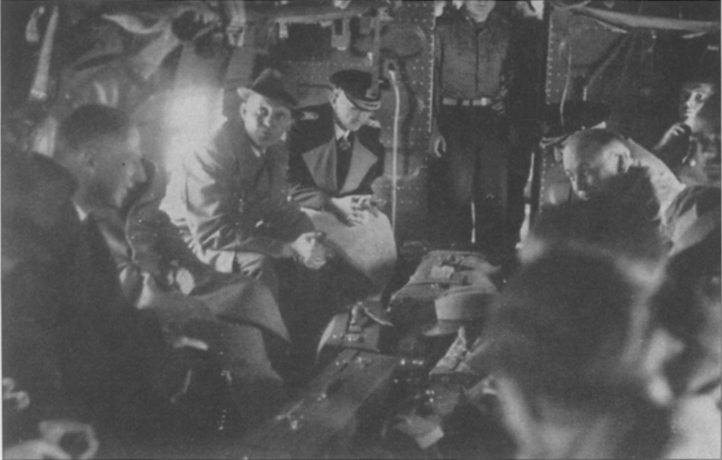

Dönitz flanked by members of his staff, directing the U-boat campaign in 1942. On the left is Kapitänleutnant Adalbert Schee, commander of U60, U201 and U2511. On the right is Kapitän zur See Eberhard Godt, head of the U-boat Command’s Operations Department.

Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and Grossadmiral Karl Dönitz at Hitler’s headquarters on 20 April 1944. Keitel also served in the Flensburg Government, and was instructed by Dönitz to sign the ratified unconditional surrender in Berlin in May 1945.

Hitler shaking hands with Heinrich Himmler on the Führer’s 55th birthday, on 20 April 1944, in Berlin. Keitel, Dönitz, and Field Marshal Erhard Milch are standing alongside Himmler.

Walter Lüdde-Neurath (left) and Grossadmiral Dönitz leaving the Flensburg Government building (then called the Stabsgebäude) in 1945.

The dramatic scene of the arrests on the morning of 23 May 1945 aboard the steamship Patria. From top left: the interpreter US Major General Lowell Rooks, Major General Nikolai Trusov of the Red Army, and Brigadier E. J. Foord of the British Army. From top right: Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, Grossadmiral Dönitz and Generaladmiral Hans Georg von Friedeburg, the last Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine. Representing General Eisenhower, Rooks announced the dissolution of the government and the arrest of its members. Asked if he had anything to say, Dönitz replied, ‘Any words would be superfluous.’ Minutes later, von Friedeburg excused himself from his personal guard and committed suicide by poison.

1000 hrs, 23 May 1945. The arrests begin. British soldiers charged into the Patria with machine guns and hand grenades, and ordered the government officials to put their hands up and their trousers down.

A full body search was conducted on all the officials, in private, before they were paraded before the press waiting outside. According to Lüdde-Neurath, workers openly plundered the possessions of their former bosses following their arrest.

Following the arrests on 23 May, Dönitz and his government were were flown to Luxembourg and installed in the Palace Hotel at Bad Mondorf, which had been converted into a prison.

At Flensburg following the arrests: Dr. Albert Speer, Dönitz and Generaloberst Alfred Jodl face the world’s press under the watch of British soldiers. Initially Speer thought that the Dönitz administration should dissolve itself following the surrender. He served as Minister of Economy and Production in the new cabinet. On his arrest, Speer said: ‘Now the end has come. It is best. It was all a kind of opera beforehand.’

Partial capitulation of the German North region, Holland and Denmark is signed on May 4 1945. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery took the unconditional military surrender from General Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg. The following day, Dönitz ordered all U-boats to cease operations and return to base.