FROM THE FIFTEENTH to the nineteen century, the power and reach of western and northern European cultures grew by powers of ten. From trading in the Baltic, hugging the Atlantic coast, and taking the dangerous leap across open water to Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland, the merchant adventurer began to cross the open sea. From journeys of a hundred miles, they went to voyages of one thousand miles, and then to travels of ten thousand miles, crisscrossing the globe.

Fed by the new trade, European wealth also grew by orders of magnitude. Trades that had never existed in the history of the earth grew and established themselves in the space of two or three years. New worlds were discovered almost weekly. News was really new, since a ship returning from around the Horn might be carrying cloth or people or art or plants or animals never before seen or described in Europe. Rice, potatoes, corn, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, peanuts, cocoa, peppers, sugar, spices, tea, coffee, cocaine, opium . . . once exotic or unknown produce became normal parts of European life. Medieval Englishmen never even heard of tea or coffee, but sitting in his coffeehouse in eighteenth-century London, Samuel Johnson could remark, “There is no illness so obstinate that it cannot be cured by the drinking of two hundred cups of strong tea.”

The world for the first time experienced itself as a whole. Political and economic organization also grew by orders of magnitude, to gather and direct the resources needed for adventure. States and navies came into existence. By the end of the period, the merchants and their naval protectors had fully justified the boast inscribed on a seventeenth-century naval medal: Nec meta mihi quae terminus orbi, “Nothing stops me but the ends of the earth.”

Sailing ships made all this possible, but in order to do so, they too had to change exponentially. Forty tons of cargo—what a good traditional Norse or Celtic ship could carry—was no longer nearly enough to repay the cost of a risky, four-year voyage. Four hundred tons was better, and better still was twelve or fifteen hundred. Furthermore, to cross the big waters, the oak timber in the old boats was far too small. A ship with planks three or four inches thick and a light frame not much thicker would break apart like matchsticks in the Roaring Forties south of the capes, where winds of one hundred miles per hour blew straight around the world without ever touching land and where the seas were often forty feet high.

In order to make ships exponentially bigger and tougher, shipbuilding was turned on its head. Up until the fourteenth century, the longships, the knars, the cogs, and most of the larger boats of Europe were built shell first. One plank was fitted and riveted to the next until the entire structure had been raised. Then a frame was inserted into the shell to improve its stiffness and to keep the rivets from working loose in rough seas.

Forest-grown oaks were best for these boats. They had grown in competition with other trees—in the Scandanavian world, they had had to outgrow evergreens to survive—so they tended to be straight and tall, with few branches until high up on the tree. Such trees contained good, straight-grained lengths for the long planks and strakes needed to form the shell-built boat.

The new ships were more like timber-framed houses than like earlier boats. They began with the frame—the skeleton—which was scarfed, lapped, and mortise-and-tenoned, and maybe bolted together. Only when the entire frame was raised was it covered with a shell. And the shell’s planks were attached not to each other but directly to the frame.

Tall, forest-grown oaks were still needed to plank these ships, but huge oaks grown in the open were now the most important ingredient. The skeleton of each ship called for hundreds of structural pieces: ribs, knees, futtocks, floors, breasthooks, keels, keelsons, sternposts, and wing transoms. In an oceangoing ship, these timbers needed to have finished diameters of between ten and twenty-five inches, and they had to be found in the exact shapes required to make the curves of the frame. Only with such a stout skeleton and with well-caulked planks could ships sail the open ocean and around the capes. Under this system, only the girth of oak trees limited the size of the ships that could be built.

Frame construction of a 74-gun ship (Nora H. Logan, after R. G. Albion, Forests and Sea Power)

More important to the merchant adventurers whose trade demanded such ships, the big boats had bottom. Indeed, the word bottom came into common use for the first time to describe the merchant ship’s broad, deep holds. A merchant was, in fact, spoken of in terms of how many bottoms were in his fleet. From this word and usage came its application to human hinder parts, and also the common nineteenth-century saying describing a shallow man as “having no bottom.” The bottom was where the wealth lay, and it also was the ballast that let the ship ride steady in rough seas.

In the fifteenth century, the new, skeleton-built ship bore different names in different parts of Europe—nef, nau, carrack—and it evolved rapidly in form and size. The caravel, a smaller ship than the carrack, was converted from shell to skeleton building at about the same time. All the new ships were too high-sided to row. They began to carry more sail, two masts and then three. Christopher Columbus’s flagship, the Santa Maria, was a carrack, while the Niña and the Pinta were caravels.

The biggest carracks were cumbersome. To resist piracy and give advantage in battle, they had very high “castles” built into the bow and the stern. These castles could be manned by soldiers armed with rifles or with small, breech-loading canons. For a century, shipbuilders strove to make higher and higher castles, since then a ship’s crew could shoot down at the enemy.

Unfortunately, high castles made the ships cranky and hard to turn. It also made it virtually impossible to keep them on a straight course. In this regard, they were the opposite of the sleek, fast Viking longships. Sir John Hawkins learned this to his cost, when in 1567 he fought the Spanish at San Juan de Ulloa in Mexico. Two of the British ships in his squadron, both small carracks, were able to maintain a tactical advantage, but the seven-hundred-ton Jesus of Lubeck was so unmaneuverable that the Spanish ran her down. She was lost with her entire crew.

A decade later, Hawkins had charge of Queen Elizabeth’s navy. His predecessors under Henry VIII had already begun to cut away the towering castles and to place larger and more efficient cannon belowdecks, where they both were more potent and better balanced the boat. He probably knew too that the Dutch were experimenting with ships that had a very low profile to the water. He and his cousin, Sir Francis Drake, championed a whole new class of faster, more maneuverable ships for Her Majesty’s navy. Drake’s own Golden Hind was a good example. When the Spanish Armada approached the British coasts in 1588, the new British ships were instrumental in its defeat. The Spanish high-castled carracks were no match for them.

The British took the lead in shipbuilding and never relinquished it until just before the end of the era of sailing ships. The vulnerability of an island nation to invasion—a lesson learned well through the Viking years when the Norse both harried and conquered large parts of the British Isles—made the navy the first priority. The British navy’s oak ships were dubbed “the wooden walls of England,” and for the more than two centuries, from the destruction of the Spanish Armada to the end of the Napoleonic Wars, those walls were never breached.

Until the age of the nuclear-powered navy after World War II, there were no strategic instruments so powerful and so far-ranging as these skeleton-built oak ships. They could carry large amounts of cargo. They could spend months at sea out of sight of land. They could mount heavy cannon. Above all, unlike even the great battleships of the two world wars, they could be repaired, refurbished, and resupplied virtually anywhere in the world. Any forest could furnish wood to patch a hole or make a mast. A merchant voyage in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries might last better than three years. Slowly but surely, these ships knit the globe together, bringing cultures that heretofore had been but shadowy legends into daily contact.

It is hard to comprehend the scope and depth of the change that overcame the maritime nations of Europe, from Portugal and Spain to the Low Countries and England. Unprecedented wealth appeared on their shores. To keep track of the wealth and to dispose it to advantage, paper currency became a potent force and stock markets were created. The old institutions creaked, groaned, and broke under the strain of so much wealth in so many hands. The wealth of kings was now but one among a number of power centers in the emerging nations, and the other holders of wealth resisted royal claims on their purses.

Kings could fall when they sought to exercise their royal prerogatives too freely. Early in the period, the English kings fell in love with big ships. Each wanted the best and biggest. James I had Phineas Pett build the Prince Royal, a ship of twelve hundred tons, almost a third larger than any other warship then in existence. It cost the unheard-of sum of twenty thousand pounds, including twelve hundred pounds just for the decorative carving.

To get the money, James invoked a primitive tax called “ship money.” Since time immemorial, the English had followed a derivative of the Viking ship levy law: In time of war, any monarch could call on his coastal subjects to provide ships and men for the navy; if a county did not want to provide the ships and men, it could instead give money. In practice, this levy was now almost always collected in cash.

There was considerable grumbling both about the tax and about the size of the ship James built with it, but his son outdid him. Charles I wanted a ship even bigger than his father’s, and the obliging Phineas Pett laid out for him the Sovereign of the Seas, the first three-decker ever conceived. It would have three covered decks, each loaded with cannon; no other ship had had more than two. It took twenty-eight oxen and four horses to drag the immense keelson (the interior part of the keel) from the Weald of Kent down to the sea. Furthermore, the Sovereign was even more decorated than James’s ship, and its tonnage was 25 percent larger.

To pay for the Sovereign and for other new ships, Charles again invoked the ship money tax. But there were three problems: First, ship money had never been collected except in time of war, and England was then at peace. Second, ship money had only been collected from coastal towns and counties, but Charles insisted on collecting it from inland regions as well. Third, he sought to make the payment a permanent institution. Essentially, he was instituting universal taxation, but he did so without the consent of Parliament, and opposition was intense. Some refused to pay it, others refused to enforce it, and though the courts sided with the king, the outcome was civil war.

When war broke out, the ill-paid naval officers and crews went over as a body to the Parliamentarians. Charles I was executed, his two sons, Charles and James, fled to France, and England embarked on two decades of parliamentary rule under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell.

Twice the younger Charles tried to return to his throne. The first time, he never succeeded in making landfall in England, but the second, he led thirteen thousand men south from Scotland, across the English border, only to be soundly defeated by the Parliamentarians at Worcester. By his own account—as reported by Samuel Pepys in King Charles Preserved—he escaped thanks to an oak tree in whose branches he hid. “We carried up with us,” Charles reported, “some victuals for the whole day, viz. bread, cheese, small beer, and nothing else, and got up into a great oak, that had been lopt some three or four years before, and being grown out again, very bushy and thick, could not be seen through, and here we staid all day.” Thereafter, he escaped to France once more.

After Cromwell’s death, there being no institutions to choose a successor, and to prevent anarchy, Parliament invited Charles to return to England as Charles II, but only under certain conditions: that he would grant amnesty to all except the men who had actually killed his father, and that all his acts would have to be ratified by Parliament before they were considered valid. In other words, he would be subject to law.

In the Parliament of 1677, the king, represented by his clerk of the admiralty, Samuel Pepys, expressed his wish to build thirty new warships. England was at peace, though the king had recently promulgated a disastrous war with the Dutch, relations with Parliament were strained, and Charles half-expected that his request would be denied. But Pepys persuasively showed the need for the new ships, specifically comparing the strength of the English navy with the navies of its principal rivals, the French and the Dutch. It was the first time in modern history that a minister had invoked an arms race in order to get his point across, but the tactic worked. Parliament voted the money for the ships.

Still, many of the representatives believed that the ships were Parliament’s or the people’s, not the king’s. One wrote, “What we give, we give not to the king, but for our own defence.” And indeed, the bill as passed mandated that all the monies for ships be kept separate from any other monies given the king, and that the ships be completed on schedule. There were penalties for lateness to be levied against contractors and even against the king himself. A general tax on all real property would raise the funds.

This was the birth of a modern state. Above all else, the state promised protection to its citizens. No one—not king, not noble, not churchman, not pirate—was to be above the government. The state itself, with its permanent corps of sailors and soldiers loyal not to individuals but to the institution itself, would guarantee its sovereignty. In return, the citizens would be free to make their own lives as prosperous as possible and would pay the state taxes to enable it to protect them.

In England, the system remained a hybrid, but more and more, the king was subordinate to Parliament’s will. Parliament had essentially given Charles II exactly what his father, Charles I, had peremptorily taken. But the son, among whose stated objectives was “not to go on my travels again,” took Parliament’s largesse kindly, even with the strings attached. His minister Pepys, who would become the prototype of a valuable bureaucrat, made sure that the ships would be well manned by getting His Majesty’s consent for further reforms.

It had been customary in the past for captains to use state ships for their own purposes—chiefly to carry cargo—when not on active duty, in order to help supplement their meager pay. Pepys had the pay of all officers and sailors immediately more than doubled, and he strengthened the prize system. Once, the Crown had taken up to half the value of a captured enemy ship. Now, the officers and men who took the prize were to keep the entire value, each receiving a fixed share. Officers might grow wealthy on their prize money, but even an ordinary seaman might put aside enough to buy a house or a farm on shore.

Pepys was himself a symbol of the change coming over England. At once a servant of the Crown and member of the House of Commons, he extolled the king while serving the interests of the nation.

Even the king embodied this mixture: In part, he was a courageous national leader, whose personal knowledge of and interest in warships assured that good ones would be built. No decorations for Charles II, no fancy royal names, no single great ship. Instead, he sought thirty ships of the line, low-slung but strong, with only broadside cannon, meant not for single action, but for battles between fleets. On the other hand, in his personal life, he supported a string of mistresses, so that part of Parliament’s strictures on the ship tax was meant to keep it away from the king’s ladies. Furthermore, nostalgic for absolute power, he conspired ineffectually with the French to restore Catholicism to England and, with it, the divine right of kings.

In 1677, fully half the revenue brought in to the treasury went to build the thirty ships. More money went for the decent pay of the officers and crews, who would now be paid in peace- and wartime both. Permanent shipbuilders were hired, who became experts in making very large ships dedicated to warfare. The ships protected not just royal interests. They also convoyed merchantmen and created a permanent threat to those who would harass trade on the high seas. They controlled and eventually eliminated private, as opposed to state-sponsored, warfare.

This emerging state supported every kind of private enterprise—including some notable speculation in shipbuilding and increasing bureaucratic corruption—but it resolutely limited the private business of violence. Piracy and private armies were suppressed at home and abroad. It was indeed possible to be a “privateer” at sea, but only with a specific license from the state. An unlicensed pirate could be hanged on capture, without further ado. The state was now the sole supplier of violence and the sole guarantor of liberty and the rule of law.

The most successful country to make this transition, England, was also the winner in three centuries of European confrontation at sea. But even in absolutist France, the change from king’s ships to national navies began in this era. Louis XIV’s great minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, capably created a set of policies of forestland preservation and shipbuilding that were the envy of Europe, including England.

English nobles owned nine-tenths of the land from which the big, open-grown oak would come, and in the House of Lords they defeated every measure meant to restrict the use or control the price of oak. Colbert, on the other hand, promulgated a forest law that marked and preserved French oak for French ships. No timber could be cut within fifteen leagues of the sea or six leagues of a navigable river, unless a written application was submitted and a waiting period of six months observed. He enforced the policy rigorously and prevented the formation of trusts that could force up the price of oak. Furthermore, he rewarded fine shipbuilding and oversaw the development of the seventy-four-gun ship, the size and draft that would become the standard for large warships through the rest of the age of sail.

The Dutch, among others, increasingly fell behind in the maritime competition, because they did not make this transition. While England and France were building professional navies, the Dutch continued to count on their merchantmen to be converted into warships at need, supplementing a few, generally smaller, dedicated warships.

For two and a half centuries, the nations of Europe clawed each other for the prize of naval supremacy. The English were always in the center of the fight. In the seventeenth century, their opponents were most often the Dutch. In the three Dutch wars, little was decided dramatically at sea, though some battles went on for days. The line of battle—a tactical philosophy under which head-to-tail lines of the largest warships ran alongside one another, battering away—was first conceived during these wars. At the start, the Dutch had three merchant ships to every one of the English. At the end, the situation was reversed.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, a third of the world’s naval power was English, another third was split by the French and the Dutch, and the rest of the world comprised the last third. The French and the fading Spanish were England’s combatants in this century, and at Malaga in 1759, it looked as though the French might prevail. They soundly defeated Admiral Byng’s squadron and captured Minorca from the English. Admiral Byng was court-martialed and shot.

But from the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759—before the French Revolution—until the final exile of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1815, the British navy dominated the French and their allies. Five French ships of the line were taken at Quiberon Bay by Admiral Sir Edward Hawke. Two decades later, at Cape St. Vincent, Admiral Rodney fought the Spanish allied with the French, destroying one ship and capturing six. At the Battle of the Saintes near Dominica in the West Indies three years later, Rodney sank one French ship of the line and took five more. On the Glorious First of June, in 1794, Lord Howe took two French eighty-gun ships and four seventy-fours. A fifth seventy-four he sank. Lord Nelson, at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, destroyed eleven of the thirteen French warships arrayed against him. Finally, at Trafalgar, Nelson put an effective end to French naval power in an overwhelming action through which the French lost eighteen ships. Nelson himself died in the battle.

By the start of the nineteenth century, oak ships had delivered Europe from the medieval into the modern world. Every coast with any resources at all was the partner or the colony of a European (or American) power. Individual liberty was a principle at home—albeit a very contentious one—but liberty was absent abroad. Oak ships had made the world a single, but unequal, community.

Into the Woods

The great, skeleton-built ships began in the woods, where imagination had to find the ships’ actual materials. Whether it was to be a sloop with a crew of twelve or a ship of the line with a crew of five hundred, the boat would be at least 90 percent oak, including all of the structural timber. John Evelyn—a friend both of Pepys and of Charles II, whose 1664 Sylva was forestry’s founding book—summarized why oak was preferred: “tough, bending well, strong and not too heavy, nor easily admitting water.” He might also have added that oak, alone among the trees of the temperate forest, regularly holds out immensely long branches at ninety-degree angles to the main trunk. Its branch crotches are wide and strong, creating just the right shapes for compass timber.

The great, skeleton-built ships began in the woods, where imagination had to find the ships’ actual materials. Whether it was to be a sloop with a crew of twelve or a ship of the line with a crew of five hundred, the boat would be at least 90 percent oak, including all of the structural timber. John Evelyn—a friend both of Pepys and of Charles II, whose 1664 Sylva was forestry’s founding book—summarized why oak was preferred: “tough, bending well, strong and not too heavy, nor easily admitting water.” He might also have added that oak, alone among the trees of the temperate forest, regularly holds out immensely long branches at ninety-degree angles to the main trunk. Its branch crotches are wide and strong, creating just the right shapes for compass timber.

The forester was as tuned to the health and shapes of trees as a physician is to the human body. He was looking for two things: big bent or crotched pieces of compass timber for the frames of the ship and long, straight timber to be sawn into thickstuff and planking. But neither the right size nor the right shape would matter if the tree were unsound.

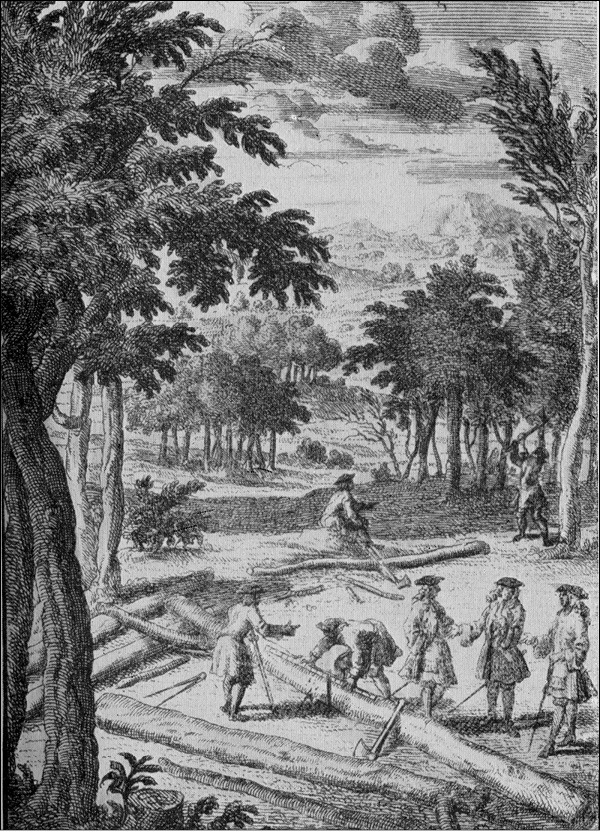

Into the woods he went: in Sussex or in the Welsh marches; in Normandy, Denmark, or Germany; in Connecticut, New Hampshire, or South Carolina. Jays and squirrels complained of his presence. His boots cracked twigs and sank in the deep duff. Where the trees grew in close mixed forests, the trunks would tend to be straight, with few branches until high in the crown. Where the trees grew in the open, they would have wide-reaching branches from bottom to top. Those were givens. Everything else was a matter for the forester’s judgment.

First, he’d look at the lay of the land. Was there a lot of projecting rock? Maybe the soils were thin. In that case, he’d look for windthrown trees to see how large they were. A tree knocked down by the wind usually had some decay at the base or in the roots. Looking around the forest, he’d judge how many trees were that size or smaller, figuring that the larger ones likely had at least some decay in their stems. The larger trees were unlikely to make good ship timber.

Were there trees that indicated poor soils? In American forests, black oak (Quercus velutina) grows where the soils are poor. Nobody would ever build a ship with black oak. Unlike the trees of the white oak group, its heartwood is porous, but white oaks growing in that vicinity were likely to be more stressed, less sound.

Maybe in some parts of the forest, the land leveled and the soils deepened, maybe at the base of a ravine or along the outwash of a brook. He’d pay special attention to the trees in that area. They’d likely remain sound longer than hillside trees.

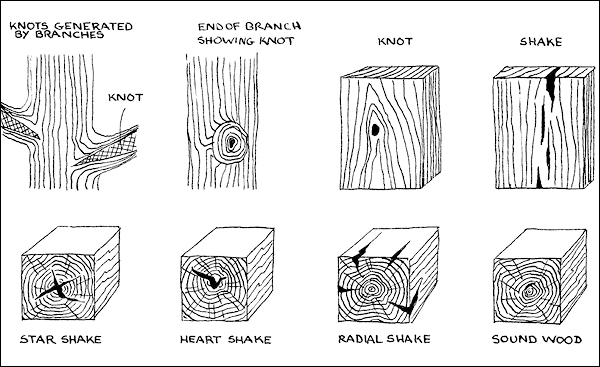

He’d look how the land faced the wind and the weather, whether the trees were sheltered or exposed. If the trees were high on a slope, exposed to sudden freezing and thawing, or to heavy winds, they might have star shakes or cup shakes inside. A star shake often begins with frost cracks formed when the bark of the young tree is exposed to winter sun; the frost makes a star-shaped pattern of fissures inside the trunk. A cup shake runs right around one or more of the annual rings, shaking it loose from the rest of the trunk. Either shake rendered the timber useless. If it were for compass pieces, the shakes would make it weak and unable to hold its place in the frame. If it were for plank, the plank would break into pieces when it was sawn out.

Some defects that ruin a ship’s timber (Nora H. Logan, after J. C. S. Brough, Timber for Woodwork)

All oak tends to flare at the base, knew the forester, but a too-dramatic flare suggested decay. How far up did this rot extend, and would it make the whole tree useless? It was hard to tell. Even were the wood above relatively sound, it might develop a heart shake, from the impaired ability of the rotten center of the tree to hold moisture. A heart shake is like a star shake, only it is wider at the center and narrower at the edge of the circumference. Still, if it extended, it would make the timber fit only for firewood.

He’d look too for cat faces, if the tree was promising plank material. Unclosed or barely closed wounds where branches have been shed often show a roundish mottled pattern on the bark that resembles a cat’s face. There would be flaws in the plank at that spot. Likewise, if he saw spiral grain, he’d know that that tree’s tissue was loaded under tension, and that when it was cut, it would likely release the energy of that bending in unpredictable ways. At the very least, the wood would want to warp, making for leaky planking or sprung knees.

When he’d chosen the trees, he’d stand by while they were cut. He waited for the smell of each. A sharp sweet tannic odor meant the butt was healthy and so, likely, was the tree. A musty or rotten odor might mean the wood was already decaying, even if it appeared sound. He’d look for any patterns of discoloration or for the presence of the black threads of fungi. He’d sound the log up and down with a hammer, listening and feeling for hollowness. The great French forester Garaud listed twenty-seven common defects in standing timber and thirty-eight more to be looked for once the tree was felled. Just as in the days before limited liability corporations, a trading firm might be rich one day and broke the next, so a tree that looked beautiful and stately in the forest might turn out to be totally rotten. John Evelyn was not exaggerating when he remarked, “The tree is a merchant adventurer. You shall never know what he is worth until he is dead.”

Even within sound wood, the forester might begin to make distinctions. If he shaved off a chip with his knife and it held together in one piece, twisting into a spiral, he knew he had lean oak with long fibers, hard to wrack out of shape and good for framing. If on the other hand, the chips were short, flaky, and easily broken, they indicated fat oak with short fibers but likely with excellent water-repelling properties. This wood would be better for planking.

The fellers’ work called for sound judgment and for care in equal measure. In recent years, machines have been developed that grab trees by their trunks, jerk them from the ground, strip off the side branches, and deliver the valuable trunk wood to the log truck. What a savings in labor it is, one the woodcutter would have admired. But he would have shouted in dismay over the waste: trunks cut carelessly high, beautiful bends at the root flare or at the branch crotches destroyed, tops left lying in heaps of refuse.

This was the work, he might have said, of a poor jobber, not a feller, not a woodsman. The craftsman went to his work with a rhyme in his head, such as the following: “Sell bark to the tanner ere timber ye fell, / Cut low to the ground, else do ye not well, / In breaking save crooked, for mill and for ships, / And, ever, in hewing save carpenter’s chips.”

Nothing went to waste. He looked at the shipwright’s molds, then found the same shapes in the trees. If the ship wood was in trunk and boughs, he would cut away the root flares to leave a smooth bole. Then, he’d make a face cut in the side toward which he wanted the tree to fall, making the cut as low on the bole as he could. This was usually stoop work. Then he’d make a back cut behind it, a little higher, but as little as possible. Early on, this was done with the same ax as cut the face. Later, a saw would be used to open the back. The sawyers for this cut—as many as four on a big tree—might work on their knees, drawing the big two-handed saw back and forth with ropes attached to each handle until the tree went over.

The feller was a practical physicist. In a wood full of trees and undergrowth, he had to make his tree fall so that it did not hang up in any other tree and so that when it fell it did no damage to the beautifully shaped crotches in the branch wood. Otherwise, a sternpost or a half dozen first futtocks or a breasthook—crucial and hard-to-find pieces on a sailing ship—might be spoiled.

He also had to prevent it from splitting in the bole, a hard job if the tree was a leaner or showed any defect at the base. If he suspected the trunk was going to split, he might reverse the usual procedure. He’d first saw in underneath the lean, halfway through the bole. Then he’d attack the root buttress on the uphill side with an ax, cutting out chips until the tree slid off its base in the direction of the lean.

If a “claw”—the angle from the base of the trunk into the root flare—was to be preserved for a knee or another curved piece of ship’s timber, he’d have to saw out all around it, then make his face and back cuts so as to leave this precious shape whole and safely in the air.

Much is revealed in the moment when a tree at last begins to fall. If the feller has done his work well, it will fall more or less in the direction it should. But if the tree is not sound within, it may split, twist about its vertical axis, and fall in an unexpected direction. This barber-chairing, as it is still called, could kill men and ruin timber. Once the notch and the back cut are made, the feller watches the tree begin to fall. Occasionally, it does not seem to fall at all. There is a moment of fascination. “Now my mind tells me the cuts are made and the tree is falling,” the feller thinks. “Why isn’t it falling?”

If he is smart, a moment later he runs just as fast as he can to one side or the other. For the only position from which a falling tree does not appear to fall is directly in the line that it is falling.

When the tree was down, he took off branch wood and selected the shapes he wanted from the shapes he’d found, laying molds over the stems and branches. Others might go in to bark the tree, pulling off everything that could be used for tanning. Children and women would come in behind, carrying off the “chips”—the waste wood—to become firewood or charcoal. Often, the foresters and fellers got the chips and the bark as their perk, and these were of substantial value.

From the felling ax, the woodcutter switched to the broad ax and began to rough out the big shaped timber for the ship’s frame. He cut notches through the trunk, figuring how broad a piece he wanted. He repeated this same cut through the whole piece and to the very same depth. He worked crossways down the log, cutting away the notches, until he was left with a roughly smooth surface. Then with a cant hook, he’d flip the piece and do just the same work on the other side. By the time he’d finished, he’d performed what almost seemed a sleight of hand: What began the afternoon as a piece of tree ended it as the rib of a ship.

It was backbreaking work and subject to cruel disappointment. The crosscuts might reveal a black and rotten heart. The old sayings about men and women, that their hearts were black or rotten, come from this disappointment and exhaustion. In the midst of the hewing, a small cup shake might widen and spread along the whole length of the piece, again making a piece of wood weighing better than two tons into lumber fit for nothing but kindling. When we say a thing is “shaky” or that we are feeling “shaky,” this is where the saying comes from: the unsound cracks hidden in the wood that make the whole piece weak and unstable. Hours of labor might yield not one sound piece.

The felling and measuring of straight, forest-grown oaks, suitable for a ship’s planking (from Brian Latham, Timber: A Historical Survey of Its Development and Distribution, author’s collection)

The costliest part of the whole endeavor was getting the timber from the forest to the yard. A twenty-foot oak log of roughly twenty-four inches in diameter weighed better than a ton and a half. (The same log in the American live oak that formed the ribs for the USS Constitution would have weighed more than two tons.) The butt of the log would be “tushed” to the harnesses of oxen and horses, who’d haul the wood out to a beach. Twenty miles was the maximum distance for this haul, and even at that it was a matter of a couple hard days’ work. This is the origin of the phrase “in it for the long haul,” which means a person will stick to a task no matter how unpleasant.

At the beach, you would think the logs could be pushed into the water and rafted together. Unfortunately for the hauler, however, oak is just about as heavy as water, particularly when it is green. To get the timber to the yard by sea, the oak pieces had to be either rafted together with lighter pine and fir or swayed up and aboard large stolid hoys, barges that could carry them along coastal waters. Sometimes, pieces might be dragged up onto a wagon and transported by road to the yard, but conditions had to be right. New Hampshire Yankees could skid their wood on sleds in the frozen winter, but in coastal Europe, the teamsters might have to wait a year or more for the road to dry out enough to let the heavy loads pass. The cost of transport represented the greater part of the wood’s price.

The Crafts Assembled

Take it all in all, a Ship of the Line is the most honourable thing that man, as a gregarious animal, has ever produced. . . . Into that he has put as much of his human patience, common sense, forethought, experimental philosophy, self-control, habits of order and obedience, thoroughly wrought handiwork, defiance of brute elements, careless courage, careful patriotism, and calm expectation of the judgment of God, as can well be put into a space of 300 feet long by 80 broad. And I am thankful to live in an age when I could see this thing so done.

—JOHN RUSKIN,

The Harbours of England (1856)

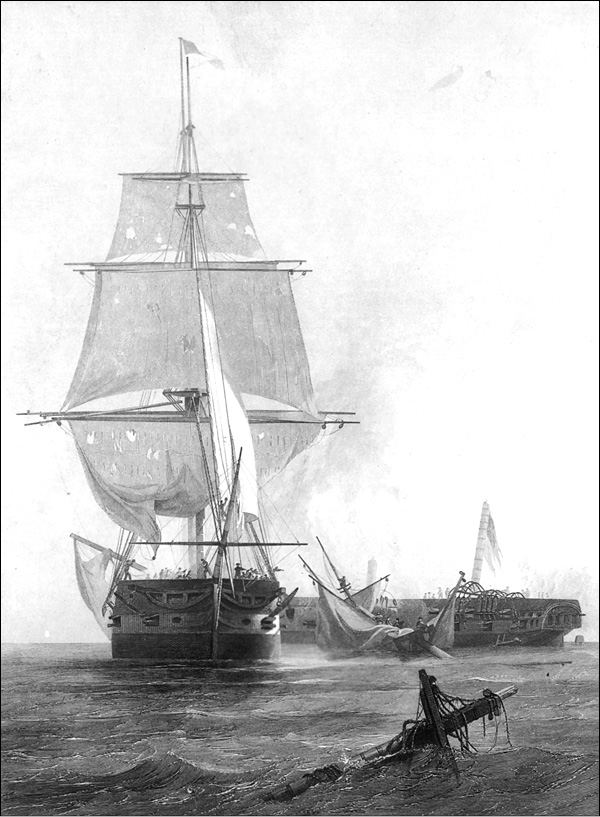

So wrote John Ruskin in his text for an edition of J. M. W. Turner’s contemporary pictures of English ports. Here, he was looking at Turner’s sublime images of the ships, lit dramatically and in ragged weather. They seem both insubstantial and larger than life. One wonders what Ruskin would have written if instead he had been standing in a shipyard.

So wrote John Ruskin in his text for an edition of J. M. W. Turner’s contemporary pictures of English ports. Here, he was looking at Turner’s sublime images of the ships, lit dramatically and in ragged weather. They seem both insubstantial and larger than life. One wonders what Ruskin would have written if instead he had been standing in a shipyard.

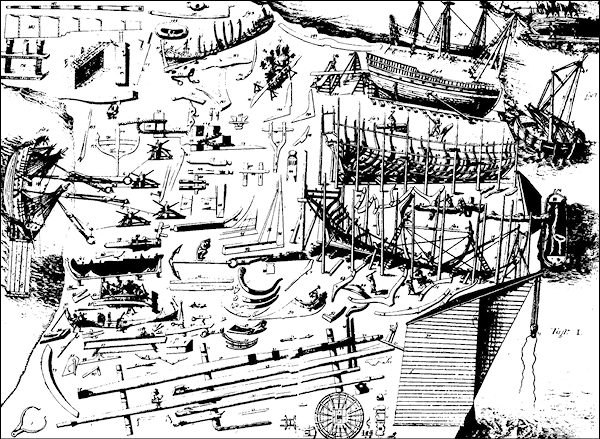

There, the hard thing to believe is that the smooth and beautiful curves of the ships standing on the stocks about to slip into the water actually came from the irregular pile of logs and sticks—long and short, straight and crooked, big and little, some with bark, some with branches, some rotten or split, some blue at the butt, some brown, some yellow—stacked, jumbled, and dropped not one hundred yards away up the beach.

In between the upstanding ship and the massed wood, there are men hewing with axes, smoothing with adzes; pairs sawing baulks with pits saws; men measuring and cutting and measuring again; men sliding half-finished timbers along a corduroy road of trunks; men turning dowels and cutting trenails; men riggng and lifting wood with block-and-tackle and cranes; men scarfing twenty-five-inch-squared baulks into long keels; men boiling pitch and mixing it with oakum to make a mess of smelly black caulking; men hammering out rivets on anvils; men snugging on planks and hammering them in against ribs or on floor pieces. Someone calls from a half-raised ship skeleton, and two dozen men stop their work to come help crane the next frame onto the keel. A bell rings, and every man shambles, scrambles, ambles, or limps over to a shed for a ration of grog. The women come sweeping into the yard to carry away the waste wood for their home hearths.

Ruskin’s wonder might indeed have increased had he seen the shipyard. For who can believe that out of such a rough pile, through such a bedlam of hacking, sawing, stewing, and lifting, comes a thing so beautiful and so capable as a great ship? Yet there they all stand together, and nobody has ever waved a wand to make the ship come to be.

A seventeenth-century shipyard (Ake Ralamb, Skeps Byggerij eller Adelig Otnings)

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the shipyards of Europe and America represented the largest industry in the world. In those yards was formed the division between thinking and making that is the hallmark of modern industrial production. The designers planned, the managers arranged, and the workers made what they were told. It was necessary to make skeleton-built ships in this way. There were hundreds or even thousands of pieces to each ship’s skeleton frame. Each had to be cut to dimensions that would allow it to snug against its neighbors, and all had to create a smooth line. If they did not fit exactly, the boat would leak.

Yet through most of the age, the thinkers still made and the makers still thought. Feedback between thinking and making—such as was necessary to craft production—continued to some degree in the organized work of the yard. The designers whittled out their models; the plankers adjusted the oak to the actual curve of the frame.

The shipyard was not yet quite an assembly line, but rather an assembly of the crafts. There had to be a wright to carve a small model and to lay out the dimensions, a forester to find and select the right timber, an axman and a sawyer to cut it properly, teamsters to tush up the log and take it to the water, hoymen to load and transport it to the yard. In the shipyard, generally located on the firm sloping beach of a “hard,” a tidal creek, there had to be pit sawyers to cut the planks and thickstuff; axmen and adze men to shape the frame pieces, beams, knees, and masts; riggers to set the keel on the stocks and to raise up the frame piece by piece; and joiners to make the trenails and to snuggle and fay, to join snugly and securely, each piece to its mate.

A skeleton-built ship was the opposite of a shell-built ship, not only in means but in the materials required. A Viking ship was 90 percent planks and only 10 percent frame timber. The carrack, the frigate, the sloop, the brig, the ship of the line—all were 75 percent frame timber, 15 percent thickstuff to stabilize the frame, and 10 percent ordinary planking to cover the sides and the decks. The average ship of the line required three thousand loads of oak, or about sixty acres of century-old trees. It took at least six months and sometimes up to three years to build.

First, a shaping imagination was needed. The great shipwrights, heirs to the tradition of the stemsmiths, knew that a sharper profile would give a faster ship, but that she would pitch and roll more, and not keep an even keel in battle. A wider profile would hold more cargo or crew and guns, but if too wide it might wallow and overpower the rudder, making the ship cranky and hard to steer. They looked for a medium between these, minimizing faults and maximizing speed and stability. Usually, they formed their ideas by looking at the work of their own teachers or at other boats they admired, sometimes even at boats captured from the enemy. They had not only to make the requisite shape of shell, but to render this planking stable with a strong, economical frame.

For most of the age of sail, the ships were too complex and too costly to be made by rules of thumb. The wright would carve a small half-model of the ship to be constructed, showing the lines of the ship from stem to stern. Owners or clients might argue and dispute over this model, but once it was accepted, it was the basis on which the ship would be built. It took eighteen tons of paper blueprints to specify exactly how the World War II battleship the USS Missouri was to be built, but the basis of a sailing ship was a small model easily held in two hands.

The wright delivered this model to the loftsman, who scaled up the model to full size, sketching out each piece of the ship on thin wood on the floor of a large room. These molds, templates of the shapes needed, would sometimes be given to the builders in the yard, who would seek the appropriate pieces on-site. Whenever possible, the timber-getters would take the templates with them into the field, to help in selecting the right pieces.

A mistake in size or shape was no small matter. The ships of the line not only took three to four thousand oaks—the American frigate Constitution took a mere fifteen hundred—but they required pieces of huge size and specific shape. Oak was never bent or constructed to make all the pieces of the up to seventy curved ribs, or the stem or sternposts, or the breasthooks, or the more than forty knees that stabilized the whole structure. Trees had to be found that had grown straight grained to the required sizes and shapes, their natural branching patterns approximating the shapes needed. A tall oak that split into two leaders near the top might make a sternpost. An oak that divided low on the trunk, grooving in a V-shape, might become a wing transom. The curved boles of wind-shaped hedgerow oaks might be turned into futtocks (the “foot oaks,” or lower pieces of the ribs) or floor pieces.

On average, to be useful for a big ship, an oak had to be seventy-five to eighty feet long and yield timber more than twenty inches on a side. The sternpost of a ship of the line had to be forty feet long and twenty-eight inches thick. The seventy ribs each required at least four long thick curved pieces of oak. Each knee had to be bent like the knee of a seated human, but it had to be twelve to fifteen inches in diameter.

Even with models and templates, the ship that was finally launched might not behave as intended. The American whaler Trident was so lopsided it had to carry 150 extra barrels of oil on one side in order to sail straight. The huge Swedish Wasa was so poorly ballasted and balanced that she sank on her maiden voyage, shortly after setting sail, when a squall healed her over, allowing water to rush into open gun ports.

Almost all shipyards were located on what the English called a “hard.” This was a clean, broad, sloping beach leading down to a tidal estuary with good deep water offshore. While the wood was gathering in, the first task was to make a slightly sloping base for the new ship to rest on. The whole enterprise depended on properly making this slip.

The word slip seems a slight one to describe a two-thousand-ton hulk sliding from the beach into the water. Imagine what it would be like to push a forty-room mansion into the sea, and you will have a good comparison, for about as much weight of wood went into a ship as into a house. We seldom say “slip” now, except for a certain kind of accident on a “slippery” surface, but more to the point for the shipbuilders was the Elizabethan use of the word, “to let slip,” or to release, as in “let slip the dogs of war.”

Ship timber found in the natural curve of oaks (Nora H. Logan)

To make the slip, the shipwrights first had to even out the ground, compacting into the surface of the beach a thick layer of rubble and gravel. Into this base, three parallel tracks, each of oak three feet wide by one foot thick, had to be laid, leading to the water. Sometimes these wooden tracks were simply snugged into the compacted surface and secured with wooden stakes driven deep into the ground. Or the tracks might be set on three rows of pilings driven into the hard’s ground. In any case, they had to be perfectly level and evenly sloped toward the water. The recommended fall was five-eighths of an inch to a foot. A little too shallow and the ship might stall on the ways; too steep, and she might shoot off the hard with enough force to ground her on the opposite bank. The outer two tracks would serve as anchors for the support beams that would rise beside the work; later they would be the foundation for the cradle that would lead the ship into the sea. The middle track had to take the weight of the whole ship. Atop it were laid thick squares of oak, the splitting blocks, upon which the keel would be erected.

The rough crooks of huge curved compass timbers had to be shaped to the exact dimensions needed. The hewer worked with the broadax, often standing atop the piece he was working. He cut out wedges up and down the length of the round trunks, working exactly to the pencil line he had drawn to mark the squared dimensions of the piece. Then he’d cut through these wedges from the sides, splitting them out, until at least the faces that needed to fit in the frame were squared. The work was exacting and done exactly. “Hew to the line, and let the chips fall where they may” is said of any man who sticks to his task through difficulties, but it first refered to the axman in the shipyard.

The pit sawyers meantime cut straight logs into planks for the ship’s sides. Either working in a pit, with the topman on the ground and the bottom sawyer below, or by raising the log onto trestles and working from trestle top to ground, the pair worked as a team. The topman aimed the saw and guided its progress, the bottom man pulled the blade through the wood. Sawyers were always hired in pairs and often spent their whole working lives together. They were not sawing out the three-quarter-inch pine boards with which we are familiar. They were sawing forty-foot-long strakes, some of which were six or seven inches thick.

Like most of the ship makers, they had learned their jobs from others. They had sayings to prompt them. “Strip when you’re cold, and you’ll live to grow old” reminded the sawyers not to get their clothes sodden with sweat and thus to avoid catching a chill when they rested. “Hard knots and empty pint pots are two bad things for sawyers” reminded them to watch out for knots in the wood, which might break teeth off the saw blade, a fate as evil as running short of beer.

Nothing went to waste. A stoutly defended perk was that three times a day the workers’ women could come to take home the chips that had been cut, for firewood or charcoal making. The sawdust went into blue-smoking fires over which tallow for graving or pitch for caulking was heated.

The dubbers followed both hewers and sawyers, finishing the compass timbers and the planks with adzes. Though the adze in many hands is a fairly rough tool, a good dubber could make an almost mirror-smooth surface where it counted—where two wood surfaces had to be fayed, or fit, quite smoothly. He didn’t waste his effort where wood would not be touching wood, however. When you look at surviving tall ships, such as the USS Constitution (now afloat in Boston, Massachusetts) or Lord Nelson’s HMS Victory (now in dock in Portsmouth, England), you see huge crooks of wood in the breasthooks and the sternposts, whose inside faces still show the curve of the branch, a strip of bark, and the collar where a smaller branch came out.

Meanwhile, riggers had set up sheerlegs, derricks, and jib cranes where the stem and the stern would start to rise. These cranes were the same as those built thousands of years before in the Mediterranean. At their top extremities they held systems of block and tackle so that men or teams of oxen could lift and settle heavy timbers on the keel.

The shipwrights supervised the cutting of scarfs on the huge lengths of keel wood, and watched as the pieces were fit in place atop the splitting blocks. The scarfs were joined with copper through-bolts, some more than three feet long. (The copper bolts for the Constitution’s keel were made in Paul Revere’s foundry.) To hold the keel in place, thick trenails (oak or black locust pegs) were wedged diagonally beside them on the splitting blocks.

From this point forward, every man in the yard was alert for the call “Frame ho!” At the word, they would stop their appointed task and go to help with the raising, swaying, and fitting of frames. First came the stem and the sterns; then came the centermost, or main, frame. Then frames were filled in fore and aft. Each frame was assembled on the ground, then raised into position, fayed into a pre-cut scarf, and bolted through with copper bolts or trenails.

Whole towns were dedicated to the production of trenails. (For the Portsmouth yard in England, for example, the village of Owlesbury, near Winchester, supplied almost all the trenails.) Trenails, whether oak or locust, had to be well seasoned so that they would not shrink. Then, when the green planking seasoned and shrank around them a tight fit would result.

When the framing was yet incomplete, plankers would mount the rising scaffold inside and out. Working in pairs, like sawyers, they would coax and bang each plank into position until it was perfectly fair with its neighbors. If necessary, they would adze off a little more here or there, but mainly they strained, hammered, wedged, and bent. When the piece was fair, they’d yell out “wood on wood!” to let their partner know the pieces had fit snugly.

Frame, plank, decks, and the ship took shape. All the workers took grog three times a day, and at those same times, day after day, the women came to collect the chips.

The designer’s role became more important as maritime competition increased. More than half of all the wooden ships ever built were constructed in the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century, the last years of the age of sail. The finest incorporated new ideas to increase speed and stability. For the USS Constitution, completed in 1797 in Boston, Joshua Humphreys and Josiah Fox had added two bright ideas. First, some of the decking was cut extra thick with matching notches, one facing forward and one facing aft. These deck planks fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The result was a fore-and-aft section on each deck that was extra stiff and extra hard to move, making the ship tighter and swifter.

More cumbersome to install were the huge diagonal riders that they specified to run from the keelson—the piece that fit atop the keel in the ship’s inner skin—diagonally up and forward until they tied into the rising frame of the ship at large standing knees. Only a few ships in Europe had yet tried this idea when it was installed on the Constitution. The point was to prevent the ship from hogging, riding up at its middle and so slowing its way. Their effectiveness was proven in the later years of the ship’s long life. When the diagonals were removed from the Constitution during the early twentieth century, she had a hog of 16 percent. When the riders were reinstalled, the hog was immediately reduced to 4 percent.

When a ship was ready to launch, the slip’s two lateral tracks suddenly became important. Using these as a base, the shipwrights built a cradle, or bilge way, on either side of the finished hull. This cradle was well lubricated with tallow. It would guide the ship into the water and prevent it from keeling over, which would ruin two years’ work in a moment. Again, the angle was crucial. Too shallow and the ship might hang up. Too steep and it might race out of control across the river. The worst result would be for the ship to stop half in and half out of the water, since the forces of sudden buoyancy on only half the ship might break her in two.

The shipwright’s last task was to scarf and bolt the false keel beneath the keel. This sacrificial piece was also called the worm keel, since it was meant to suffer damage—whether from boring worms or running aground—while protecting the true keel, upon whose integrity the structure of the ship depended.

One by one, they knocked out the splitting blocks and let the ship rest on its false keel, straight on its track into the water. They installed a screw mechanism facing the stems, well anchored to the ground. Often, too, they rigged blocks and tackles from the existing cranes to help encourage the ship down the ways.

When it was time to launch the Constitution in 1797, the naval constructor, Col. George Claghorn, had every dignitary present from President John Adams down to the customs house clerks. He knew that her sister ship, the USS United States, had gone too fast down the ways in Philadelphia, had piled up on the opposite shore of the river, and had had to be repaired before ever she put to sea. Perhaps this inclined him to be too cautious, for with thousands in attendance, the Constitution scarcely budged on the ways. She went about twenty-seven feet, then hung up, a portion of the track apparently having settled.

Everyone went home, while the opponents of naval expenditures began to hoot and holler. That afternoon, with no one present, Claghorn tried again. This time she got to within a few feet of the water, but again hung up. Imagine the frustration of men who had put two years of their lives into this majestic structure, only to find it refusing to enter the sea.

But he’d lost his tide. Claghorn had to wait a month for the next water high enough to float her. Finally, in mid-October, when the last red and yellow leaves were blowing off the maple trees in Boston and with no one but the builders present, the Constitution journeyed the last few feet down the ways and floated on her own bottom.

Constitution

After Nelson’s crushing defeat of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Great Britain had by far the most powerful navy in the world. To finally strangle the French, royal orders were issued to prevent neutral nations—notably the United States—from trading with the French. In addition, to keep up the ranks, which had been depleted by battle, disease, and desertion, of more than 140,000 sailors needed to operate the immense British navy, the English not only pressed Englishmen out of English merchant ships and from their own homes, but also American citizens from American merchant ships.

After Nelson’s crushing defeat of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Great Britain had by far the most powerful navy in the world. To finally strangle the French, royal orders were issued to prevent neutral nations—notably the United States—from trading with the French. In addition, to keep up the ranks, which had been depleted by battle, disease, and desertion, of more than 140,000 sailors needed to operate the immense British navy, the English not only pressed Englishmen out of English merchant ships and from their own homes, but also American citizens from American merchant ships.

Impressment was lawful kidnapping. During wartime, the British navy was permitted to seize any able-bodied man unable to prove he practiced a “protected” trade. Fishermen, ferrymen, iron founders, and others whose work at home was thought crucial were given letters meant to exempt them from the press. In actuality, the “letters of protection” that poor apprentices carried with them were often torn up by the press-gangs, and the men taken anyway. As the need for sailors increased, the British began to search American merchantmen for “runaways,” but in practice, they took anyone they wished.

In his war message to Congress on June 14, 1812, President James Madison complained first and foremost of the “thousands of American citizens, under the safeguard of public law and of their national flag, [who] have been torn from their country and everything dear to them” and forced to become British sailors.

The point of American democracy, as President Madison saw it, was to protect the liberty of America’s citizens and the freedom of her trade. On June 18, war was declared.

July 17, 1812. About two P.M.

The United States frigate the USS Constitution stood on the starboard tack, headed north by east with every scrap of canvas spread. The breeze was light and fluky. Capt. Isaac Hull was bound for New York, where he was to rendezvous with Commodore Rodgers’s squadron in order to harass British shipping.

There was only a froth of foam at the sharp cutwater as the ship made way. High above this white apron rode her figurehead. Its maker, William Rush, described it thus: “An Herculean figure standing on the firm rock of Independence resting one hand on the fasces, which was bound by the genius of America, and the other hand presenting a scroll of paper supposed to be the Constitution of America with proper appendages, the foundation of Legislation.” No god of wind or war surmounted the bow of this naval vessel. It was and remains the only naval ship ever named for and symbolized by a piece of paper.

The lookout at the masthead hailed the quarterdeck. He made out four sail of ship inshore to the south-southwest. Thinking this might be Rodgers’s squadron, Hull altered course to intercept them. Even were it the enemy, he must have reasoned, his orders had specifically stated, “You will not fail to notice any British ships that you may encounter.” Two hours later, another sail was descried coming from the north. As day was waning, Hull decided to make for the single ship first to see who she might be.

At about ten that night, he had closed to within a few miles of the stranger and caused the private signal to be made. The signal was kept up for more than an hour, without answer. This ship, at least, stood a good chance of being the enemy. Hull stood off to the east to await the dawn.

As the sun came up, his heart sank. There in his lee were two English frigates, with a third directly astern of him. Less than a dozen miles off, he could make out another frigate, a ship of the line, a brig, and a schooner, all in hot pursuit. Seven to one. Not good odds for a fight, and just as Hull made his plans to escape, the wind died completely, leaving him without even steerageway. The Constitution was not in command. Her head slewed around so as to face the pursuers, who still enjoyed a light breeze and were consequently coming up fast.

The Constitution was the pride of the tiny American navy. Commissioned in 1794 to help defend the growing American merchant marine from Barbary pirates in Mediterranean waters, she was not launched until three years later. She and her sister ship, the United States, were both forty-four-gun frigates, unusually large for that class of ship. On the other hand, at the outset of the War of 1812, the entire U.S. Navy totaled seventeen ships.

The young American nation had the second-largest merchant marine in the world, but the smallest navy of any major power. The British navy, on the other hand, constituted about nine hundred ships, half the total naval strength of the globe. Furthermore, frigates were but the light cruisers of the British navy. Its greatest strength lay in its ships of the line, huge two- and three-decked ships capable of carrying from seventy-four to more than one hundred heavy cannons.

Since naval warfare consisted of two opposing ships ranging up close alongside each other and battering each other’s hulls, rigging, and personnel with cannonballs, chainshot, and grapeshot fired at point-blank range, the larger, heavier, and more heavily armed ship tended to prevail. Almost all the cannons were located on the sides of the ship—hence the term broadside for the full discharge of all cannons on one side of the ship—while the bow and the stern were weakly protected, if at all. When one ship was faster and more maneuverable than another, or when one combatant had its enemy outnumbered, a ship might maneuver into position to “rake” the opponent’s bow or stern. A broadside fired into a warship from either of these positions could do terrible damage, both to the ship’s structure and to her crew. During most of the quarter millennium in which sailing warships were the principal instrument of state power abroad, the gundecks, where the bulk of the crew gathered to fire the cannons, were painted red, so as not to show blood.

Isaac Hull must have had blood, wood, and wind on his mind as his new charge drifted out of control and pointed his eyes straight at the oncoming enemy. Once the first enemy ship came up with him, all it would have to do would be to sufficiently wound the Constitution’s rigging so that the ship’s speed and maneuverability would be impaired. Then, all the British ships could range up alongside and compel the American frigate to surrender or be destroyed.

He had to run, but to run, he needed a breeze. The Constitution was a fine ship, made principally of live oak (Quercus virginiana) from the Georgia sea islands and white oak (Quercus alba) from New England. She was stiffened with the designers’ diagonal braces, and Hull had recently had her bottom cleaned of barnacles. If only the wind would come up, he might yet get away. Otherwise, he would have to either send his crew to slaughter or surrender one of the two largest ships of the U.S. Navy.

Surrender was by far the more likely alternative. Indeed, in the whole era of sailing navies, the object was less to sink the opponent than to compel him to strike his colors. The vanquished ship might then go to become part of the victor’s own navy. Indeed, among the flotilla pursuing the Constitution, one frigate, the Guerriere, had been captured from the French back in 1805. (French warships were in vogue among British captains, since they tended to be faster and more maneuverable than English-built ships.) The brig Nautilus had been captured less than a week earlier from the Americans. The Constitution stood fair to become the latest addition to the British commander Commodore Broke’s growing squadron.

Still, Isaac Hull had two great advantages: a willing crew and an unusually well-built ship. American sailors were recruited, not pressed or drafted, into the navy. While the service was hard and desertion common, still the American sailor could count on a rate of pay five times better than his British counterparts. President John Adams had fixed salaries for American ordinary seamen at ten dollars and for able-bodied seamen at seventeen dollars per month, comparable to skilled craftsmen’s pay onshore and higher than merchant seamen. And like British sailors, all American seamen shared in the prize money when they captured enemy merchantmen or warships. Furthermore, American seamen signed on for a year at a time, while conscripted English sailors might spend years without hope of even shore leave.

The Constitution had no trouble finding a full crew of sailors—475 in total—before she left the Chesapeake Bay on July 12. True, Hull’s crew was green—just a week out of port, and some had never sailed before—but he had been drilling them at the guns and in the rigging several times each day. They were about to face one of the stiffest tests in naval history.

The other advantage was no less telling: The Americans had by far the best ship on that patch of ocean. European dockyards had been building sailing warships for better than 250 years. Though fine building oak was common throughout most of Europe, the resource had been strained to the limit not only by naval and merchant building—merchant shipping used three times as much oak as naval—but by the competing uses of oak for buildings, charcoal, furniture, bridge timbers, roads. Furthermore, the best open-grown oak flourishes in what also makes the best wheat fields. Croplands made money much faster than oak forest, so many fine oaks were cut simply to make room for fields. “The proper diminution of oak,” as one writer put it, showed the vigor of the British economy. Wars were being fought in Europe for control of the Baltic trade, whose main commodities were oak plank, wood for masts, pine tar, and other naval stores. European builders had to economize, both on the thickness of their planks and on the size and spacing of the ribs that formed the structure upon which the ships were erected.

No such limitations faced Joshua Humphreys and Josiah Fox when they designed the Constitution. Shipbuilders usually sought either great strength or great speed in their ships. The thick sides and squat dimensions that made for the former represented a choice against the slender proportions and lighter construction for the latter. Unencumbered by traditional European habits and economies—on the Continent the French always built for speed while the English built for staying power—Humphreys and Fox went for both strength and speed. The Constitution was three feet wider and twenty feet longer than the average British frigate; she was a foot wider and thirteen feet longer than a standard French frigate. The Constitution’s live oak ribs were spaced less than two inches apart, while the ribs in most European ships were a foot apart. The close-spaced rising ribs were more than framing; they acted as an additional wall. When white oak planking was added both outside and inside, the total thickness of her hull at its strongest parts was better than twenty-two inches, where the European ships seldom managed more than fourteen inches, and that with widely spaced ribs, between which the ship was vulnerable.

The result was a ship that might well be both faster and stronger than any frigate in Europe. The heavy timbers, which would tend to slow the boat, had been offset by giving her a sharper profile and, above all, by stiffening her sides. By increasing the number of ribs and by adding diagonal braces, the American designers managed to dramatically reduce hogging. They got a frigate bigger than any other, while at the same time probably faster.

The “probably” Isaac Hull intended to try, if he could only find a breath of wind. Meantime, his enemy was closing on him, though now the wind was dying for them as well. No sooner had Hull seen the position he was in than he had all the Constitution’s boats put over the side. The rowers towed the ship’s head around, and began laboriously to drag her away from her pursuers.

As soon as the British hit calm water, they too put boats over the side and began to row furiously toward the Constitution. Four of the British frigates were almost within gunshot when the American First Lt. Charles Morris had an idea. He’d just heard the leadsman call the depth at twenty fathoms, not too deep to anchor. He suggested that Captain Hull warp ship.

This was a practice seldom used except when bringing a ship to anchorage or freeing it when grounded. The idea was to tow a two-and-a-half-ton anchor tethered both to the ship and to the belly of one of the rowboats out as far ahead of the ship as possible, cut the anchor loose from the rowboat, let it take ground, and then have the sailors at the capstan in the ship’s bow essentially “wind” the ship forward until it reached the submerged anchor. While this was going on, another boat would take the second anchor out as far as possible and repeat the procedure. It was as though a fisherman had cast his lure out as far as possible, snagged it on the bottom, and then drawn himself, boat, line, reel, and all, up to the snagged lure.

Why not? Around eight in the morning, the ship’s boats began warping the Constitution across the open sea. Sailors strained to pull out the heavy anchors with the additional weight of their twenty-two-inch cables. Others strained to reel the capstan in order to pull the ship forward. They pulled with a will for about an hour, but if anything, the British were still closing.

One of the enemy frigates fired a broadside, but it fell short. Half an hour later, a second frigate tried to reach the Constitution with a shot, but they were still just a hair too far off.

For three hours, all hands on all ships continued the backbreaking pursuit, the Americans warping forward and the British towing up behind. The rhythm of the work must have encouraged each side alternately: When the Constitution had just warped up to her anchor, she must have felt she was escaping. Then, in the changeover to the second anchor, the British must have thought their steady rowing made them just about to overtake their quarry. From the vantage point of heaven, it must have looked like a race between slugs and an inchworm. By two in the afternoon, men must have been dropping from fatigue.

Then Commodore Broke had a brainstorm. He had the ship’s boats from seven different ships at his command. Why not use the boats from all of them to tow the leading frigate—the Shannon—up to the fleeing Constitution? No sooner said than attempted. It is important to imagine the heart of the Americans, who saw this happening, and who just kept on warping ahead.

It was a formative moment for what would become one unvarying feature of the American character. Who could understand an outgunned, outmanned, and outdistanced frigate that would just keep on going? The sun westered and sank over the Atlantic coast, and the Americans were still warping. The evening star shone in the sky, and the Americans were still warping. British frigates were almost up to them again and again, and the Americans just kept on warping. Dinner came and went, the dogwatch came and went, and the Americans just kept on warping. Row. Drop. Reel. Row, drop, reel.

It was eleven at night on July 18. The Americans had been warping for fifteen hours without a pause. The Constitution was barely, just barely, holding her own against the seventeen boats trying to bring the Shannon up to her. Just one solid broadside from the British frigate, and the Constitution would be as good as caught.

About a quarter past the hour, Isaac Hull felt something on his cheek and tried to brush it away. Then, he knew it for what it was: the puff of a breeze. Quickly, he sent topmen aloft to prepare to set sail. God willing, the breeze would hold. God willing, they would get to race the whole damn British navy.

At twenty past, he gave the order to set tops and courses. It was a crucial moment. If the breeze had died at that instant, the dropping sails would have become an impediment, resisting the capstan turners and possibly slowing the Constitution just enough to lose her. But the breeze held. She gathered way. White foam appeared beneath the figurehead.

Quickly, Hull signaled the boats, who were about to be overtaken. They swung alongside, their crews vaulted aboard, and hauled up their boats without the loss of an instant.

The British, seeing the Constitution under sail, immediately followed suit. They picked up their boats and came on through the gathering dark. All that night, Hull led them a chase. At dawn the next morning, one British frigate was close enough to fire on her, but the British captain held his fire, probably afraid that in the light air the recoil of his cannons would becalm his ship.

About nine in the morning a strange sail appeared. The British, thinking it likely an American merchantman, hoisted American colors to try to decoy her into a trap. But Hull hoisted British colors, and the American hauled his wind and made off to the southwest.

All that day the Constitution fled, with a rising wind in her sails. A squall came up about sundown, but Hull had seen it coming, furled and reefed to meet it, then unfurled and squared away the moment it had passed. It was brilliant sailing, perfectly executed by a willing if exhausted crew.

After the squall, perhaps Hull thought for the first time, “We’re going to do it. Damn it all, we’re going to do it!”

The breeze kept freshening through the nighttime hours. At daylight on July 20, two full days after the chase had begun, only three sail of the enemy could be seen from the masthead, and those three were at least six miles off. Hull wet his sails to improve their performance and kept cracking on.

At eight-fifteen in the morning, the British gave over the chase and hauled their wind to the south-southwest, apparently for New York to set up a blockade of that port.

A lone American frigate had outsailed an entire British squadron. As the Constitution’s sails receded before him, Commodore Broke must have wondered whether this tiny American navy might be the beginnings of a formidable opponent. Scarcely one month later, he would have his answer.

Isaac Hull was daring, but he was not a fool. Immediately after his escape, he made for Boston to reprovision and to replenish the water that he had thrown over the side to lighten the boat during the chase. He waited there impatiently for instructions from Washington or from Commodore Rodgers, but none were forthcoming. When the wind shifted into the west on the August 2, allowing him to sail out of Boston harbor, he reluctantly decided to sail without orders, first writing a letter to the secretary of war, explaining his reluctance, his reasons, and his intentions. Boston was a hard harbor to get out of, the winds being often contrary, he wrote, and if he remained longer, he might find himself blockaded in by a superior British force. Nonetheless, he would not sail south to give Broke’s squadron another shot at him. Instead, he’d sail northeast to the principal shipping lanes of British Canada, hoping to wreak havoc there on British merchantmen and to recapture any American ships that might have been taken as prizes and sent, lightly manned, to British harbors.

The three major British ports in Canada were Halifax, Nova Scotia; St. Johns, Newfoundland; and Quebec City, Quebec. If you imagine the Canadian coast as a mouth, St. John was on the upper lip, Halifax on the lower, and Quebec City in the throat. The Gulf of St. Lawrence was the bulk of the mouth, and the St. Lawrence Seaway the throat. By placing himself just offshore of the lips, Hull could prey on the ships bound in or out of any of the three ports. He counted on his belief that his British counterparts either were doing the same thing in American waters or were actively blockading American ports.

On August 10, he had his first success, running down a small British brig bound to Halifax from St. John. Brigs were the principal type of merchant vessel in use throughout the world. They had two square-rigged masts, sometimes with a schooner-rigged sail trailing on the main mast. They were the original tubs, meant to carry as much cargo as possible, not too quickly but very safely, with a small crew. This one must have been dwarfed by the 147-foot-long, three-masted Constitution. She carried no cargo of note, however, nor was the ship worth much in herself. Hull took the crew off and burned her.

A day later, he came on a bigger prize, the British brig Adeona, bound from Nova Scotia to England with a full load of timber. Again, he took off the crew and burned the ship. Four days after, he sighted five sail of ships. Closing on them, he found a British warship (but a mere sloop, a single-masted craft) and four of her prizes. One was already aflame when the Constitution approached. Two were American brigs, which he liberated. The sloop of war got away.

From the crews of these ships, he got information that Broke’s squadron was on the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. If the hounds had come north, reasoned Hull, the fox would head south. He set his course for the waters off Bermuda, where he expected to harass British ships entering and leaving the Caribbean.

On the night of August 18, he chased another brig, which turned out to be the American privateer Decatur. So concerned was her captain to escape the big ship that loomed up on him out of the dark that he had pushed overboard twelve of his fourteen cannons. To no avail. The Constitution brought him to after less than an hour’s chase. The captain told Hull that the day before he’d seen a large warship to his south, and that she could not be far away. In fact, it seems that the Decatur’s captain had thought the Constitution to be that ship come in chase of him.

The Constitution continued her course southward, hoping to fall afoul of this supposed warship. At two in the afternoon on August 19, running before a steady north wind, Hull got his wish. He was in midocean, about due south of Cape Race, Newfoundland, and due east of Boston, 318 miles from the nearest land. The lookout at the masthead cried a sail to the south-southeast, too far away to say what sort of ship.

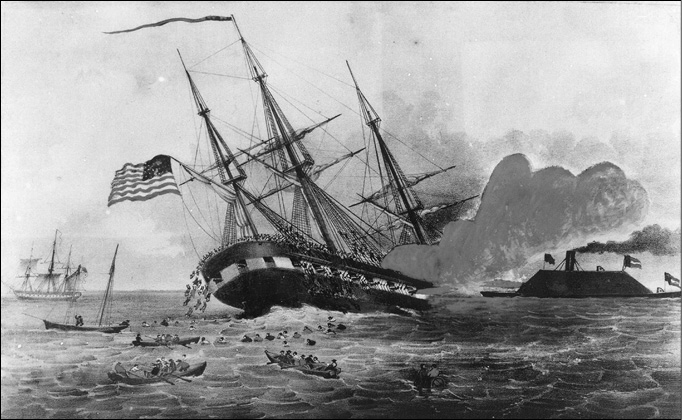

Hull squared away and gave chase. An hour later, they were closing fast. Their quarry was a large ship under easy sail on the starboard tack, making no effort to get away. By three-thirty, it was plain that this was a large frigate, and not an American. In fact, it was the Guerriere, lately part of Broke’s squadron, but now cruising alone. Her captain, Richard Dacres, was a distinguished second-generation British naval officer. There were impressed American seamen aboard the Guerriere, and when they saw what was afoot, they earnestly requested of Captain Dacres that they not be compelled to fight their own countrymen. Part gallant and part practical, Dacres sent them below as noncombatants. The last thing he would need in a close action would be crew members who might suddenly fight for the other side.