WHAT IS A FRUIT? What is a nut? A dessert? A snack food?

A short time ago the Kornbluths, a young Orthodox Jewish couple living in Brooklyn, called me in my capacity as arborist to come and look at their pear tree.

“We need to know if it can bear fruit,” Mrs. Kornbluth said over the phone.

I asked her why she thought the tree couldn’t bear fruit. She said that an arborist had looked at it recently, told them it was full of carpenter ants, dying, and should be removed immediately. No, he had told them, it would never bear fruit again.

“It sounds awful,” I responded. “Why not just remove it, as the arborist suggested? Why call me?”

“We want a second opinion,” she said. “You see, under our law, you cannot cut down a fruit tree if it can still bear fruit.”

We talked for a long time, Mrs. Kornbluth and I. She had many questions. She wanted to know if I could positively, definitively tell them that it would never bear fruit again. I was envisioning a tree three-quarters gone with root decay, dieback on all the stems, and with a very short time to live. I said I could not say with 100 percent certainty, so long as the tree lived—only God could do that—but I could give a reasonable probability. This was all very important, she explained to me, because they wanted to build an addition to the house that they had just purchased. If the tree could bear fruit, they could not proceed. She asked, and I told her my consulting fee. She said she’d talk to her husband and their rabbi and would get back to me. Once she’d hung up, I wondered what kind of culture would show such apparently exaggerated respect for a single fruit tree, and why.

The next day, she called to set up a meeting at the tree with her and her husband. I arrived twenty minutes early and walked around behind the house. I was nervous, anticipating that this would be a very hard call. I wanted to get a head start on the tree, without anxious watchers hanging over my shoulder.

My mouth fell open. I did not see a dying pear full of ants and root decay. I saw a vigorous pear, squeezed in a corner though it was, with leaders jumping up above the roof of the house. It was full to the brim with fat flower buds—the month was January—and almost every growing tip showed large lateral scars down the stem behind it, indicating where a fruit had been.

I was astounded by the difference between the story that the Kornbluths had been told and the story I had to tell them. I doubted the evidence of my own eyes, since I could not believe that the other story—in which I had implicitly come to believe—could be wrong. I had been preparing to try my best to assess the chances of a dying tree, and suddenly I had to tell them about a healthy one. What is more, I knew how Mrs. Kornbluth wanted the story to end. She wanted to build her addition. But she did not want to break Jewish law.

When they appeared, I was disarmed. They were slender, earnest, intelligent, and very young. They had a toddler in a stroller and a babe in arms. She had dark almond eyes and a long green winter coat. He was dressed in black from head to foot, with the fine, black, broad-brimmed hat that the Orthodox wear and a fresh, blooming, reddish beard.

I said what I had to say: the tree was almost certain to bear fruit again, barring an act of God, a bolt of lightning, or the destruction of every other pear tree within five miles that might pollinate it. (Pears are not self-fruitful; they need another pear in order to bear fruit.)

I pruned part of a young branch to show them what I meant. They were chagrined. Had I hurt the tree? No, I said, pruning is good for trees, if it is done judiciously and correctly. They were amazed. They decided to ask their rabbi whether they ought to prune the tree instead of removing it.

Through all of this, I felt bad. I could see the house they’d bought and their two children. I had no idea how many kids they wanted, but you could see that they were delighted to have a family. The house was not large. An addition would have seemed just the right thing to continue their story.

“I’m sorry I don’t have better news,” I said.

The husband—he must have been ten years my junior—looked at me and with only the slightest vehemence said, “This isn’t bad news. This is very good news. Because you have prevented us from doing a thing that is wrong. It is good news, and I am very happy about it.”

This brief speech impressed me deeply. He was not being self-righteous. He didn’t seem to be trying to win a point against his wife, either. In fact, he appeared to be trying to enjoy obeying an ancient law, even though it might make his life less stable and less ordered. I had known numerous clients and would-be clients quite willing to remove bearing fruit trees and huge centenarian oaks simply because the leaves were littering their yards and clogging their gutters. They were ready to kill a creature more than one hundred years old in order to spend one day less each year sweeping leaves. This man needed to make a bedroom for a child, but he wouldn’t kill this tree to do it.

“It’s a good law,” I said. Neither of them replied. But a strange law, I thought to myself. Where had it come from?

On the way back down the driveway to the street, I started to identify other plants on their property, partly to console them, I suppose, partly because I was nervous in front of them, and partly because I felt that I had hardly earned my consulting fee. It didn’t take a genius to know that that tree would fruit. When we got to the small front garden, I showed them a euonymus shrub that had the usual scale infestation, and a pair of lovely upright junipers. “The berries of these junipers,” I remarked in passing, “are not eaten anymore, but are sometimes used to flavor gin.”

“Ah,” they replied. They asked how to treat the scale and about the identities of other plants on the property line. We parted.

Three days later, I got another call from Mrs. Kornbluth.

“What was that you said about jam?” she asked.

I was nonplussed. “I didn’t say anything at all about jam,” I answered.

“You said one of the plants in front was used for jam. Our rabbi says that that makes it a fruit tree, and we cannot cut it down.”

Uh, oh, I thought. I must have put my foot in it again.

“I don’t understand,” I confessed.

“Since we can’t build the addition in back,” she explained, “we decided to build it in front, but if those trees are used for making jam, we cannot do that either!”

“Mrs. Kornbluth,” I said, “no tree I saw at your house, except the pear, could be used in making jam.”

“But you said so clearly,” she insisted.

The light dawned in my memory. “Gin!” I exclaimed. “Not ‘jam,’ I said ‘gin.’ The berries of the juniper are used in making gin.”

“The drink?” she asked.

“The liquor, yes,” I said.

“I hear,” she said. “I will have to ask the rabbi. May I call you again?”

“Of course,” I replied. I saw that I was indeed going to earn my fee.

The next day, I heard from Mrs. Kornbluth again.

“Can you move those trees, the gin ones?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, “in the right season, of course I can. They are not very large, and they are easy to move.”

“Will they grow and be healthy?”

“God willing, yes,” I said. “They should be fine.”

“Good,” she said. There was deep relief in her voice. At last, the young mother was going to get her house in order.

“But if you don’t mind my asking,” I went on, “no one eats the juniper berry, at least not anymore. The Apaches may have eaten it once, but now it is used only to flavor gin. Does that make it a fruit tree?”

“Yes,” she said. “The rabbi explained it like this: We use the quercitron in our festivals. It is very bitter, and yet we prepare it and use it sparingly to flavor. So it is a fruit. And even things like oats or wheat, these are changed and prepared before we use them, and parts of them are thrown away.”

Just so. Through the Kornbluths, I began to see deeper into time. The juniper berry had indeed been a food to the Apache and to many others. The law of the Kornbluths was more than three thousand years old and might preserve in its pages the memory of a time qualitatively different from ours. I have read the book of Genesis since I was a child, but now for the first time it occurred to me that God had told Adam and Eve to eat the fruit of every tree in the garden, except for one.

To eat the fruit of the trees. Not for dessert. Not as a snack food. To live on the fruit of trees.

What if this were not a poetic manner of speaking, but a description of what people, before agriculture, really did? I had loved the acorn-eating cultures of the Indians of California, where I grew up, but always considered the eating of acorns a habit peculiar to these small, rotund people on the edge of the earth.

What if they were not the only, but only the last of, the balanophages?

Balanophages: acorn eaters.

The Old Stories

Just as we have legends of an Arcadian past, in which pastoral peoples lived on the edge of the Mediterranean, so those pastoral peoples themselves had legends of a past in which people ate the fruit of oak trees.

Just as we have legends of an Arcadian past, in which pastoral peoples lived on the edge of the Mediterranean, so those pastoral peoples themselves had legends of a past in which people ate the fruit of oak trees.

There is a whole class of old stories that speak of such ancient, prehistoric systems. The question is, were these stories largely made up, or have they more than a grain of truth? To begin with, remember that Troy and Mycenae were thought to be baseless legends until some intrepid archaeologists unearthed them. And though in the nature of things it is impossible to unearth a balanoculture—that is, a culture that lived on nuts—still we may find the story compelling in its truth.

In the eighth century B.C., the Greek poet Hesiod, in his Works and Days, asserted that acorns effectively prevented hunger: “Honest people do not suffer from famine, since the gods give them abundant subsistence: acorn-bearing oaks, honey, and sheep.”

The poet Ovid repeated the acorn story in Fasti, the work of his maturity, which was meant to be a poetic retelling of the feasts of the Roman calendar. Under the feast of Ceres, goddess of grain and agriculture, he recounted that prior to the age of agriculture, people lived on acorns. “The sturdy oak afforded a splendid affluence.” Ovid was a contemporary of Virgil and Horace, and their equal as a poet. He was certainly not bandying words about lightly. When he wrote “affluence,” he did not just mean that acorns were yummy, but that they dependably provided people with plenty to eat.

Lucretius repeated more or less the same tale, with the addition that oak was so important to people’s lives that acorn-decked oak boughs were carried in procession in rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Pliny, the most audacious and voracious story collector of his time, described all the different oaks of which he was aware and their many uses. “Acorns at this very day,” he wrote, “constitute the wealth of many races, even when they are enjoying peace. Moreover also, when there is a scarcity of corn they are dried and ground into flour which is kneaded to make bread; beside this, at the present day also in the Spanish provinces a place is found for acorns in the second course at table.”

Pausanias, in his Description of Greece, written about the year A.D. 160, described the founding of the kingdom of Arcadia by Pelasgus, who, he reports, invented the use of houses, the wearing of sheepskins, and the eating of acorns. An interesting trio: home, clothing, food. It sounds very much like the foundation of what we would call a human life.

Pausanias writes, “He too it was who checked the habit of eating green leaves, grasses, and roots always inedible and sometimes poisonous. But he introduced as food the nuts of trees, not those of all trees but only the acorns of the edible oak.” The suggestion is that, by creating a staple food, Pelasgus was able to create a sedentary life for his people, perhaps the first of its kind. Though Pausanias was writing about what to him was antiquity, he notes that still in his own time, the Arcadians were fond of acorns.

To my mind, however, one of the strongest bits of evidence is not even a story. It is just a word. The old word for oak in Tunisia means “the meal-bearing tree.”

Later writers in the Latin west picked up the antique stories and passed them on, at least for a period of time. The English Renaissance poet Spenser put the matter clearly and beautifully in his pastoral “Virgil’s Gnat”:

The oke, whose Acornes were our foode before

That Ceres seede of mortall men were knowne,

Which first Triptoleme taught how to be sowne.

Recently, however, we have come to think these early writers credulous. Everything written before the Scientific Revolution smacks of hearsay. After all, Pliny contended among numerous other unsupportable assertions that buzzards were impregnated by the wind. How then can we trust him and his confreres and their progeny on a matter so important as the origins of human eating habits and of settled life itself?

No, the modern scientific thinkers knew the truth, and the truth was red in tooth and claw: Pre-agricultural man had been a hunter. Only when he’d exterminated most of the game and when a change in climate further reduced his hunting stock of large quadrupeds did he change to shepherding and agriculture.

Nuts? Oh, prehistoric man sometimes ate them, just as we do today.

In fact, early “scientific” prehistorians remade ancient man in the image of an industrial capitalist. Of course they sought the largest game, and of course they destroyed as much of it as they could. And of course they would have gone on destroying it until some worldwide change forced them to alter their habits, that is, to innovate, to create a new way of life. That is the march of progress, that is the way things are.

But the researchers who followed these bold theorists began to find unexpected difficulties with that hypothesis. In fact, people had evidently eaten not just large game animals, but rather anything they could lay their hands on, from turtles to snails to eggs to acorns. Furthermore, there never had been any change in climate such as had been proposed. Third, in archaeological finds, there appeared to be grinding tools before there was any evidence that even wild wheat had been cut for human consumption.

What were people grinding?

Perhaps the book on which the Kornbluths’ faith is based can give some answers. Genesis has a good deal to say about fruit trees. In the first creation story, which comprises the first chapter of the book, God concludes, “See, I give you every seed-bearing plant all over the earth, and every tree that has seed-bearing fruit on it to be your food.” There is no mention of animals as food.

Chapter two of Genesis contains a second creation story, thought to have been composed before the first. This is the tale of the Garden of Eden: “Out of the ground, the Lord God made to grow various trees that were delightful to look at and good for food, with the tree of life in the middle of the garden.” God tells Adam, “You are free to eat from any of the trees of the garden, except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.”

In our curiosity about the identity of the Tree of Good and Evil, we lose sight of the main point: that God tells unfallen Man to eat the fruit of trees. What fruit trees were available in Mesopotamia’s Fertile Crescent after the end of the last ice age? Oaks, junipers, pistachios, maples, and wild pears. (Yes, Mrs. Kornbluth! Pears.) Of these, all were likely eaten, but the one that had the proper nutritional characteristics to become a staple food was the acorn.

How far that time seems from this! Oaks have been cut down without a thought around the world for three thousand years, though not, I suppose, in any place where the Kornbluths’ rabbi or his ancestors and teachers were to be found. But they are not forgotten as a source of foodstuff everywhere or by everyone.

Recently, I took a walk in the heart of New York City’s Little Korea on Thirty-second Street in midtown Manhattan. Someone had told me that Koreans still eat acorn products, and that if I looked in a good Korean supermarket, I might still find something.

In the middle of the block was the biggest Korean market in the city, and behind the cash register was a beautiful girl with long straight black hair and a face shaped like a slender acorn of the white oak. I asked her if she knew if there were any foods made from acorns in her store, and she looked mystified. She queried her neighbor at the next register—“Hawgon?”—and she too shrugged her shoulders.

Unwilling to go away empty-handed, I rummaged around in my change pocket, where I usually keep at least one acorn. Sure enough, there was a red oak acorn that I’d collected a few months earlier in New Hampshire. The girls were by this time looking at me dubiously and nervously.

I drew out the acorn and held it up. This, I said, and pointed.

Immediately, the two broke into smiles and laughter. “Of course, of course,” said the black-eyed one. “Yes, we will show you.” The acorn was obviously as familiar to them as a pinto bean or a rice grain, though not by the name acorn. They led me back to the flours, where they picked out a pound of acorn starch flour for $5.99, and then to the cold case, where there was a tofulike square of acorn jelly for $3.99. All the while, one of them kept trying to explain to me how to prepare the jelly from the powder.

Perhaps Pliny and Ovid and Pausanias and all the others were not wrong. Maybe whole cultures once ate the fruit of the oak. If we are children of the Northern Hemisphere, our ultimate fathers and mothers likely fed on acorns.

The Meal-Bearing Tree

A few kids in New England and the upper Midwest still know that if you find a fresh “oak apple” on a red, scarlet, or black oak, you can poke a hole in it and suck out the sweet juice. Most have probably been cautioned against such a risky and unsanitary practice, but even to this day the Kurds, Iranians, and Iraqis swallow the sweet exudate from the oak tree, which they call “manna.” Both juice and manna are the distillations of oak sap.

A few kids in New England and the upper Midwest still know that if you find a fresh “oak apple” on a red, scarlet, or black oak, you can poke a hole in it and suck out the sweet juice. Most have probably been cautioned against such a risky and unsanitary practice, but even to this day the Kurds, Iranians, and Iraqis swallow the sweet exudate from the oak tree, which they call “manna.” Both juice and manna are the distillations of oak sap.

Each June and July, the Kurds wait for the sweet drops to begin to congeal on the leaves of Quercus infectoria. Early in the morning, before the ants have had a chance to visit the leaves, they beat the branches over a cloth laid out on the ground, dislodging the crystallized manna. Sometimes it is brownish, sometimes greenish, sometimes as black as tar, and sometimes pure white, but always it is very sweet. They use it to make a breakfast drink, or they mix it with eggs, almonds, and spices to make a delicious, sweet cake. Records from the early twentieth century show that at that time the Iraqis consumed more than thirty tons of this cake each year.

Through all of antiquity, it was thought that this manna dropped from heaven. (The biblical manna of Exodus may have been the same exudate but from the tamarisk tree.) In fact, it is the product of aphids and scale insects, who insert their mouthparts into the sweet elaborated sugar and carbohydrates that run through the phloem just beneath the tree’s bark. They digest what they can—primarily the scarce nitrogen—and the rest passes through them and drips from the trees.

The oak apple is not an oak fruit; it is a gall (see pages 294–301). Each gall is protected with layers of bitter tannic tissues on the outside, but the innermost chamber is full of the same sweet juices that the Kurds and the Hebrews tasted and that enterprising kids still taste today.

But both kids and Kurds have a sweeter time with the oak than did the millions who ate acorns as their staple food. Acorns smell delicious when you begin to prepare them. You crack off the shell and grind the meat into meal. It gives off a pungent, fulfilling scent, with the richness of olive oil and the tang of coffee. This fragrance is even more pronounced when you leach out the tannins with copious amounts of water and put the meal into a low oven to dry.

The taste is, to put it mildly, disappointing. One modern writer called the flavor of porridge made with acorn meal “insipid.” “Absent” might be nearer to the mark. There is a definite presence and texture to the stuff, satisfying on the tongue and going down the throat. But flavor? Not a bit. Tap water is tastier.

The first prepared oak food I ate was the acorn jelly from the Korean supermarket. It was kept with the tofu in the refrigerated section, and like tofu, it came in a little square immersed in water and wrapped in a decorated plastic container. It was a lovely chocolate brown color; compared to the tofu—which has always looked to me like fat bathroom tiles—acorn jelly looked delicious.

I sliced it and ate it cold. It hit the tongue with a slimy slipperiness, like touching a slug, but fortunately, it almost immediately began to dissolve. It was lighter in texture than Jell-O, and the sensation of it, after the first shock, was pleasant. The only real trouble was that it had a flavor about as definite as the air coming out of an air-conditioner vent.

This would not do. I tried frying it in olive oil. This was better. It tasted like olive oil. I sliced it thin, grated scallions over it, and added sesame oil and rice vinegar. That was delicious, but the jelly had contributed texture and mass alone, not a molecule of flavor.

This experiment took place in the middle of the morning and was a disappointment to me. I went back to my books, wondering how anyone could have stomached stuff like this for a week, never mind several thousand years. Not that it was noxious, just vacuous. They would have died of ennui.

On the other hand, it was a great deal of fun to read about eating acorns and to talk to those who studied them. I went on with these enjoyable tasks for some time. When I noticed the time again, I was surprised to find that it was past three in the afternoon.

Never in life have I needed a clock to tell me when it was lunchtime. If I have not eaten my lunch by one or so, I begin to grow short-tempered and cranky. Fernando, the foreman at my tree company, judiciously suggests that the men may be getting hungry, in order to induce me to go buy food before I start getting angry.

This day, however, I had had a banana and coffee for breakfast, followed by six slices of acorn jelly—around four ounces—at ten-thirty. Then, nothing.

At three o’clock, I was still not hungry. Nor was I hungry at four. I went straight through to dinner without any wish for lunch or snacks, and I did not become cranky. Sometime in the middle of the afternoon, it occurred to me that the reason might be the acorn jelly. I now recognized the last sensation produced by eating it: After swallowing even the first piece, I had immediately had the pleasant feeling in the pit of my stomach of being full.

More experiments were called for. I pulled out a cookbook called Acorns and Eat ’Em, which had graciously been sent me by the author, Suellen Ocean. She lives near Willits, California, in the northern coastal mountains, where good acorns are plentiful. She loves frugality, and she loves eating off the land. People in Willits call her the Acorn Lady, but she longs to be known as the Betty Crocker of the Woodland. She is the sort of person who, if you called her an unregenerate hippie, might proudly nod assent.

Suellen’s spiral-bound cookbook contains several dozen recipes using acorns to make everything from breakfast cereals to dinner entrées, including acorn lasagne and acorn enchiladas. There is nothing at all exotic about her recipes, no effort to imitate Native American cooking. She simply wants to make this abundant, free, healthful food a regular part of her—and of everyone’s—diet.

The following Saturday morning, I made Suellen’s acorn pancakes, using the acorn flour I’d bought at the Korean supermarket. Her recipe is a standard flapjack recipe, with a third of a cup of acorn meal thrown in. They cooked up a little higher, and they browned better than ordinary pancakes. Indeed, they were also a pale brown color inside. They tasted fine, a little chewier perhaps. The acorns added no flavor, but they did add that odd feeling of being very quickly filled and satisfied.

Five hours later, I still felt that way.

Next, I decided to try a recipe where acorns were the principal ingredient, not an addition to an otherwise serviceable dish. The ingredients for Suellen’s acorn spinach burgers include a box of frozen chopped spinach, a cup and a half of acorn flour, two eggs, and a half cup of flour. Acorns and spinach are the main event. You make patties and cook them up in vegetable oil.

The results were not appealing to the eye. My first two burgers looked like mud pies studded with gravel, and the texture was unpromising as well. Just as I was extracting them from the pan, my wife happened in.

“Not very appetizing, are they?” I asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. Let’s try them,” she ventured.

We broke off two shards from burger number one. There was hardly any flavor, as usual, but the texture was much more appealing than its appearance would suggest. With a little salt, the pieces were definitely palatable. Dipped in Thai chili sauce, they were tasty. Slathered with prepared horseradish, they were positively delicious.

I felt that I had discovered the first principle of acorn cookery: Mix it with something that has flavor.

I recalled reading that the Kurds still relish a dish made with acorn meal and buttermilk, and since I had some buttermilk, I added it to the acorn-spinach mix. The results fried up into tasty fritters, enriched by the pungent buttermilk. More horseradish didn’t hurt either.

By the time I’d finished this experiment, I was full to bursting, though I’d eaten not much more than half a cup of acorn flour. I felt that I could eat acorn indefinitely, so long as I varied the flavorings. And perhaps too, I reasoned, since I could count on the fingers of one hand the occasions in my life when I had gone hungry, I might not value as highly the pleasant sensation of fullness as do those who have been hungry more often.

It occurred to me that acorn might well have been the foundation of all the stews and hot pots that are still the mainstays of cuisines throughout the temperate world. If indeed acorn was the staple food, it would have called out to be flavored, spiced, varied, and embellished. And if, as a number of anthropologists now think, the culminating state of hunter-gatherer culture was one in which everything from seeds and nuts to fleshy fruits, meats, fish, shellfish, turtles, insects, and berries were consumed, it would have been natural to develop a cookery based not on roasted or boiled meats but on mixed stews.

If the evidence of those who still eat acorns is taken into account, this seems to be exactly what happened. The Chinese still prepare a stew of leached acorns and water chestnuts in brown sauce. The Turks, too, still prepare racahout, a hot drink or porridge of acorn meal mixed with vanilla, sugar, and other flours. Into the nineteenth century, the Ojibway, the Menomenee, and the Iroquois of the American Northeast and upper Midwest ate acorns flavored with maple syrup, blackberries, meats, and bear oil. They sometimes mixed acorn flour with maize flour to make bread. The Apache made a pemmican of acorn flour, venison, and fat. Cahuilla cooks in southern California vary the flavor of acorn by mixing it with chia seeds, berries, or meats, then cooking the mash until it forms jellylike cakes that can be sliced and eaten exactly like my Korean acorn jelly (only tastier). Elsewhere in California, different tribes had their own favorite additions—roots, seeds, berries, and fungi. Even where they made a plain acorn mush by boiling the meal in water, they might lend it flavor by leaching the meal through aromatic leaves or by dripping the water into the leaching pit over a branch of incense cedar.

Delfina Martinez, a Pomo woman living near Hopland, California, told me about the feast days of her childhood. Her mother would build a fire and let it burn down to coals. Then she would layer wet leaves on top, followed by a layer of acorn mush, followed by a layer of salmon, followed by a layer of leaves, followed by a layer of acorn mush, and then a layer of venison. They’d keep adding layers until the pile was more than four feet high, then cover it with earth and wait until morning. All the children vied to be the first ones up in the morning, the first to open the dish and begin to eat it.

Acorn was also eaten more or less plain, as a nourishing way-bread. Such breads are recorded around the world, and some are still regularly made. Sometimes the meal is mixed with clay or with hardwood ashes—a process supposed to sweeten any remaining tannins—but whatever the admixture, it comes out dark and crusty on the outside, with a spongy texture inside. The Tartars of the Crimea were still eating it at the end of the nineteenth century. In Corsica and Sardinia and in North Africa it is sometimes still eaten today. The California Indians all ate acorn breads, and the naturalist John Muir called the acorn cakes he learned to make from the Indians “the most compact and strength-giving food.” It was easily portable, very nutritious, and it kept for months without spoiling.

Where acorns have been most favored as food, there have often been species reputed to be quite sweet, or at least to have definite flavor. The Cahuilla ate four different varieties, and it is said that a good cook could vary the flavor of her mush by combining the four in different proportions. Acorns from the sweetest species have evidently been eaten roasted and salted, as snack foods. In Japan and Korea, the acorn of the species called kunugi, a variety of Quercus acutissima, are sometimes so eaten, as are the acorns of Q. emoryi in northwestern Mexico. (The onetime importance of kunugi in Japan may be shown by stories that claim in ancient times there were kunugi so large that at morning and evening their shadows stretched for hundreds of miles.) The fruit of Quercus ilex—the circum-Mediterranean evergreen oak—are still a popular festival food in southern Spain and in Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. Up until the early years of the twentieth century, the favorite snack of the ladies at the grand opera in Madrid were roasted salted acorns.

Acorns have even been boiled to extract their oils. The oil is sometimes used as an unguent and disinfectant, and it is effective at stopping bleeding. But in parts of the globe as far separated as Morocco, Minnesota, and Mendocino, the oil has been used in cooking. In Cádiz, Spain, it is still possible to get acorn oil as an alternative to olive oil, and in Extremadura, also in Spain, there is an acorn liqueur.

That acorns are still eaten in so many ways and in so many parts of the world argues that they might once have been a staple food.

After the Ice

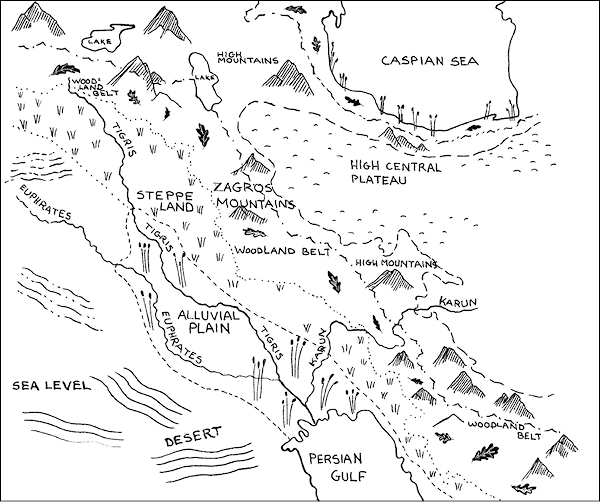

The later Pliocene folded land, the Pleistocene scoured it. In the Pliocene, continental movements brought tectonic plates into contact, pushing up new mountain ranges around the world. These folded into parallel ridges, much as the bedcovers make a series of ridges when you push them down from around your neck. Often, the mountains descended in cascades, from high ranges to steppes to high valleys to lower ranges down to a low alluvial valley, stepping down like grandstand seats.

The later Pliocene folded land, the Pleistocene scoured it. In the Pliocene, continental movements brought tectonic plates into contact, pushing up new mountain ranges around the world. These folded into parallel ridges, much as the bedcovers make a series of ridges when you push them down from around your neck. Often, the mountains descended in cascades, from high ranges to steppes to high valleys to lower ranges down to a low alluvial valley, stepping down like grandstand seats.

In the Pleistocene, the ice flowed southward around the world, reaching its maximum penetration toward the equator by about twenty thousand years ago. Large areas of North America, Europe, and Asia were covered, though California was not and neither were Japan, most of China, and much of Southwest Asia. Average temperatures, even in unglaciated areas, declined precipitously, and the oak retreated into protected refuges. Areas that are now deserts—the Sonoran of southwest North America or the Negev in the southeastern Levant—were then covered with oaks. Major populations of oaks survived on the south coasts of the Black and Caspian Seas, and in scattered savannahs on the coast of the Levant, the northern Mediterranean, and Turkey. In China, open steppes and conifer forests dominated, while the oaks remained in the subtropical south and east. In Japan, oaks remained mainly in southeast coastal areas.

When the ice retreated, the oaks flowed out of their refuges. Frequently, they chose pathways that led along the uplands created by the new Pliocene mountains and high valleys. Out of the Negev, they cloaked the coastal hills of the Levant, traveled along mountain slopes in Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan. To the north, they met other oaks emerging from the Black and Caspian Sea refuges, and journeying along the hill country of the Zagros Mountains, in what is now southern Turkey, and eastward into the land above the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in Mesopotamia. Oaks rimmed the Fertile Crescent. The oaks from the Levant also turned west and reached into southern Greece. All of this happened between twelve and eight thousand years ago.

About the same time, oaks came north from the Sonoran refuge in southwestern North America and spread north along coastal and interior uplands along the length of the Pacific Coast. In eastern North America, they came north from the southeastern plains along the old lines of the Appalachian uplands, reaching into northern New England by around eight thousand years ago.

The glaciers stayed long in Europe, so it wasn’t until about ten thousand years ago that the European oaks, pasted up against the Mediterranean at the edges of the Italian and Spanish peninsulas, started north. They reached Britain and southern Scandinavia within two millennia, and shortly thereafter, at the warmest moment of the current era, they even extended northward into interior Scandinavia.

In China and Japan, the oaks were the quickest to expand their range. By nine and a half millennia ago, the oaks of China had covered the central and northern uplands and reached along the coast into Korea and Siberia. In Japan, by twelve thousand years ago, the oak had reached once more through all but the northernmost islands. By eight thousand years ago, they had colonized even Hokkaido.

Oaks occupied all zones as the climate warmed, but as the temperate weather stabilized and dried, areas of the plains became less suitable to the them. Refuges like the Sonora and the Negev became deserts, and oak disappeared from them. North America’s southeast piedmont retained some oaks, but they declined in density. Everywhere, however, they thrived in the uplands of the folded mountain belts.

This is the scaffold, I believe, on which human beings emerged. Not hominids, but humanity: the kind of humanity described by Pausanias, with houses and clothing and a supply of staple food. Postglacial man appeared among these stair-step mountains and valleys, ranging up the ladder to the mountains and high steppes to hunt game, such as wild sheep and goats, down to the watered plains to seek crabs, mussels, snails, and migratory birds, but living in the uplands where acorns were the staff of life, and where small wild grains fed the first domesticated animals.

Systems like this, where many different climate belts lie in close proximity—stacked one upon the other, really—and where opportunities for hunting and gathering are most various and most plentiful, are called vertical economies. Such vertical economies appeared virtually simultaneously in places thousands of miles apart: the Zagros Mountains and the Tigris and Euphrates Valley in Mesopotamia, the Jordan Rift Valley and the Judaean Hills in the Levant, the Arcadian hills of Greece, the central highlands of China, the Indian vale of Kashmir, the coast range of western North America, the highlands of Tehuacán in Mexico, the river-fen-upland complexes of central and northern Europe. Everywhere the economies were diverse—depending on a far wider variety of food sources than we do today—but everywhere they were centered on the upland belts of oak trees.

An archetypal example of a vertical economy, from plains to steppes to uplands and mountains (Nora H. Logan, after Kent V. Flannery, in “The Ecology of Early Food Production in Mesopotamia,” Science 147:3663 [1965]: 1249)

Take, for example, the place of Eden, as it is described in Genesis. “A river rises in Eden to water the garden; beyond there it divides and becomes four branches. The name of the first is the Pishon; it is the one that winds through the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold. The gold of that land is excellent; bdellium and lapis lazuli are also there. The name of the second river is the Gihon; it is the one that winds all through the land of Cush. The name of the third river is the Tigris; it is the one that flows east of Ashur. The fourth river is the Euphrates.”

This is a fairly precise description of a place with a vertical economy comprised of the Zagros Mountains down through the oak-pistachio uplands to the Assyrian steppe and finally into alluvial Mesopotamian bottomland. The settled villages that developed here were among the first in the world.

It was once thought certain that the peoples of this region at first depended on hunting large ice-age mammals. Then, when these were exhausted, they were supposed to have turned to wild sheep and goats. Later, they were to have domesticated these same sheep and goats, to make them more readily available for consumption. And finally, they were to have taken advantage of the wheat and barley that grew wild and in profusion both among the upland forests and out on the open alluvial plains. First, they were to have collected the wild grains and processed them; later, they were to have begun to cultivate them. This story was presented as a progress from the uncertain and famine-dogged life of the hunter-gatherer to the relative security of agriculture and domestic animals.

The story turns out to be almost wholly false. At the least, it needs to be stood on its head, and one major omission—the acorn—needs to be rectified. Among the largest early settlements in the Fertile Crescent was a town of thirty-two acres called Catal Huyuk, adjacent to the upland oak belt in the Konya Plain of present-day Turkey. It flourished around eight thousand years ago, just as the practice of agriculture began in the area. Archaeologists at the site uncovered both grinding implements and cement-lined subterranean storage pits. These were taken to be evidence of early farming based on the indigenous wheats and barleys. Indeed, in the later strata, not only wild strains but also genetically altered cultivated grains were found.

But there was a problem. Among the early remains there were very few if any sickles, and none of the few that were found had the characteristic sheen found on blades used to cut grass stalks. The people might have plucked up the grass plants by the root, as is still done in some parts of the world, but to do so would have meant to break many seed heads and lose the precious grain. They would only have pulled the whole plant if their intent was to use the whole plant. And the only possible use for the stalks as well as the seed heads was not as human food but as animal fodder.

If they were feeding their wheat and barley to the sheep and goats, what were the people of Catal Huyuk eating? What were they grinding with their grinders and storing in their storage pits?

They were grinding and storing acorns. The Catal Huyuk people were perhaps the last of a culture that had fed on acorns as its staple food. Only later did they reverse the feeding strategy, cutting, preserving, and threshing grains for human use, while feeding acorns to the animals. As late as the end of the nineteenth century, traveler Isabella Bishop came upon villages in Kurdistan where the people ate acorn bread, wild celery, and curds—sometimes making a kind of special pastry of the curds and acorn meal together. They did indeed grow wheat and barley, but they did not eat these. Instead, they traded the grains for cotton and tobacco.

For how many thousands of years did people in these upland belts subsist on acorns as a staple, supplemented by everything from goat meat and snails to barley tea? How secure a life was it? Weren’t whole regions constantly in danger of famine? Did they not turn to agriculture for greater security?

Evidently, balanocultures were among the most stable and affluent cultures the human world has ever known. Kent Flannery, who studied the Middle Eastern peoples of this time and was among the first to debunk the idea of the big-game hunters turned to farming, wrote in a 1965 article, “Hunter-gatherer groups may get all the calories they need without even working very hard.” Another researcher concluded that in the Zagros uplands near Eden it took ten times less labor to harvest acorns than it did to harvest wheat and barley. Another noted that a diet based on acorns was far more nutritious than one based on wild game, and far easier to acquire. David Bainbridge, who studied acorn use in California’s surviving balanocultures—and who coined the term balanoculture—concluded that local oak uplands could routinely support villages of one thousand people, and these people could harvest enough acorns in three weeks to last two or three years. The nuts could be stored in above-ground aerated bins, in subterranean lined pits, or even buried at the edge of stream courses where the acorns would not only keep fresh but also be leached of their tannins by the passing water. Early European settlers in the American Northeast frequently reported that while plowing low spots near old stream courses they turned up caches full of acorns.

Acorns were nutritious, easy to acquire, and easy to store. The only laborious step in their preparation was leaching. Because of the high proportion of tannins and other astringent compounds in their meat, in order to make them palatable it was important to grind the nuts and wash them in water. Every culture where acorns were found had the technology to do this, though in southern Europe and North Africa, the acorns of the evergreen oak Quercus ilex were often sweet enough simply to roast and eat.

When there was plenty of oak gruel and oak bread to eat, it was unnecessary to slaughter every animal you caught. The origin of the domestication of sheep, goats, and pigs may have come because with a staple of acorns it was possible to save captured animals, breed them, and so have a “bank” of meat against possible famine. Probably, it was these animals who first were fed on the wild grains and grasses, as well as on the leaves of oaks.

With comparatively little effort, then, the people of the oak cultures could have acquired their daily bread, doing exactly as the God of Genesis specified, by eating the fruit of trees. There would have been only a basic division of labor: The men might take responsibility for expeditions in search of dietary supplements or for the more strenuous aspects of acorn harvests. Women and children could have performed the entire harvest, leaching, and food preparation. There was no shortage of oak trees in the postglacial uplands. There would have been plenty of time to stop and reflect, plenty of time to become human beings.

But if this were the case, why did anyone ever change?

Threads of Oak

For perhaps one to three thousand years, people did not change. They lived on acorns, supplemented by an increasing variety of meats, nuts, grains, spices, and herbs. It is usually suggested that human migration is caused by famine, war, disease, crop failure, or some other disaster. Perhaps in these beginnings of human cultures, it was more often caused by affluence.

For perhaps one to three thousand years, people did not change. They lived on acorns, supplemented by an increasing variety of meats, nuts, grains, spices, and herbs. It is usually suggested that human migration is caused by famine, war, disease, crop failure, or some other disaster. Perhaps in these beginnings of human cultures, it was more often caused by affluence.

Settled, peaceful society meant two things: First, it encouraged the birth of many more people. This led not only to more pressure on the food resources, but also to more diversity in the society. Different lineages developed their own aims, customs, wishes, ways of life. Because there were few disruptions, distinct groups tended to survive over many generations. Second, settled society sent the local environment into decline. Although the touch of these comparatively small groups was light compared to ours, still they required both wood for heating and for building and fodder for their animals.

The combination of woodcutting and livestock grazing could prove devastating: Cutting coppice, that is, cutting a tree down to its rootstock every ten to fifteen years, produces abundant wood for heating, cooking, and building, and given enough time, an oak will usually respond by putting out vigorous new growth and creating healthy new stems. If goats are present, however, they will gnaw down the tender new shoots again and again, until the root system runs out of energy for resprouting.

Growing population and degrading landscapes encouraged emigration. These would likely have been acts not of desperation but of boldness and vision. A daughter group would conceive of its destiny as separate from the village’s and set out in pursuit of it. They would be forced neither by hostility nor by hunger. Rather, they would set out well provisioned and with great hopes. And so long as the upland chain of oak forests persisted, they would not suffer want.

The scale of this early migration is hard to exaggerate. Wherever oaks spread in the waning of the Pleistocene and the growing warmth of the Holocene, human populations could follow. The Indo-European root word for oak is daru, and a derivative of that word survives in the Celtic word for oak, dru, of which druid is a form. Is it possible that this word was passed from mouth to mouth and from generation to generation, from central Asia to northwest Europe, by people following the thread of the oaks?

There is no need for the impulse to have begun in one single place, once for all, and then spread around the world. It might indeed have begun in many places, wherever people first learned to leach and eat acorns. One impulse could have started near the oak refugia on the southern shores of the Black and Caspian Seas, then penetrated east along the Zagros to the Persian Gulf and south into the uplands of the Levant, eventually turning the corner into North Africa, where acorns are still common in the average diet. Another impulse could have originated in southeastern China and penetrated up through the Chinese central highlands, along the edge of the steppes and into present-day Korea and Siberia, jumping thence into Japan. A third impulse could have been transmitted from the Zagros into southern Greece and Italy, on to the Iberian Peninsula, and north into northern Europe as far as Scandinavia. A fourth impulse might have begun in the Mesoamerican highlands and moved north into California and east through the continent’s southern tier, then up the Eastern Seaboard. Or was the California oak culture a product of people coming over the Bering land bridge from the comparably strong oak cultures of the Korean Peninsula?

Such transmission of human culture could have continued for millennia. The exact mix of foods would have changed according to what was available in different locations, but everywhere acorns would have been the staple. (Only in eastern North America might rival nuts have been eaten more often. There hickory nut, walnut, and butternut are tastier, as available, and as nutritious.)

Eventually, however, the spread of balanoculture would have met two obstacles. The first would have been climate. Though oaks themselves have succeeded in adapting far into the zone of snows, people are not so adaptable. More northerly balanocultures would have had to make decisions about whether to use oak as a source of foodstuff or as a source of building and heating materials. Indeed, the only places where balanocultures have survived until recent times—Japan, coastal Korea, North Africa, and California—are areas with mild climates.

The second obstacle lay behind the front of migration, in the older acorn cultures. There not only had pressure on the wood resource had much more time to build up, but the land would have continued to get poorer. Between eroded hills and voracious goats, oak woodlands began to decline. The era of plenty was drawing to a close.

Every culture has a mythic history of a former golden age of plenty. It may be that these sacred histories are, on the literal level, memories of balanoculture.

The Fall

At first, the people probably did not think that they would stop eating acorns. They were just adding other foods, either for flavor or as alternatives, maybe following a poor mast year, a season when the oaks bore few acorns. The culture of their fathers and their father’s fathers had been nurtured on acorns. So would theirs be. But look: Here too was turtle soup, here were snails, here were other nuts, here was goat meat and goat milk, here was the meat and fat of acorn-fed hogs, here were grains.

At first, the people probably did not think that they would stop eating acorns. They were just adding other foods, either for flavor or as alternatives, maybe following a poor mast year, a season when the oaks bore few acorns. The culture of their fathers and their father’s fathers had been nurtured on acorns. So would theirs be. But look: Here too was turtle soup, here were snails, here were other nuts, here was goat meat and goat milk, here was the meat and fat of acorn-fed hogs, here were grains.

One problem with balanoculture is that oaks do not bear equal annual crops. Some years are far heavier than others, and occasionally—in a season of cold and drought, say—the size of the crop might have been insufficient. Then, people might have looked to other foods: The grass that they fed to animals had edible seed heads. Parch the seed heads slightly, and the tough coverings—tasty to goats but indigestible to humans—would come off easily. The seeds could be ground into flour, using the grinders that had been invented to grind acorns into meal. The grain flour could be baked into a bread, which was lighter than acorn bread though it did not keep as well. In this way, people learned to use grains as food, even though it is unlikely that they ever would have had to depend on them.

Not until they moved away from oaks. The great flaw in balanoculture is that you can’t take it with you. You have to go where the oaks are. True, in order to maintain balanocultures, customs grew up to support the propagation of oaks. In Germany and Switzerland, a law survived into the Middle Ages that required a young man contemplating matrimony to plant two young oak trees prior to the nuptials. By the time the couple’s children were ready to marry, there would be two more fruit-bearing trees to help sustain them. But since the time from the planting to an oak’s first fruiting is between fifteen and thirty years, the cultivation of oaks as a fruit tree has never been practicable.

The first people to move away were likely young and hopeful. Like their grandparents, who had moved from one oak grove to another in order to have their own way of life, free of the old people and their too-settled ways, this young group would have looked abroad and felt the need for a change. “Why should we stay here?” they said. “Everything is already decided here, and we have nothing to do but live and die. Let’s go make our own way.”

“Where can we go?” asked a doubter.

“Down there,” said her friend. She would point down into the open plains, the stepped, alluvial valleys, where there were few trees but abundant grasses. “We could bring wood and build there. We would have plenty of feed for our flocks, and we could trade fodder to get acorns.”

Gradually, the whole group was won over. They gathered their supplies, said their good-byes, and moved. Someone knew a good knoll with ready access to water, as well as a seasonal shepherd’s hut and enclosure. It would be a good place for the village.

For the first two years, they had regular contact with their old friends up the slope. They traded fodder for acorns, and skins for timber. But it was a long uphill trek, and the old people were none too welcoming to the upstarts who’d abandoned them. Why not, said the bright woman, cook the grain right here? After all, it’s all around us.

For those of us who laboriously cultivate wheat, oats, barley, rice, and other grains, it is hard to conceive of the natural abundance of the wild grains in the places where they were first plucked, threshed, hulled, ground, cooked, and eaten. Back in the 1960s, botanist Jack Harlan made an excursion to one such site in the Near East, where he found thousands of acres of uncultivated, wild emmer wheat. With a primitive flint sickle, he succeeded in gathering by hand over the course of three weeks more than a metric ton of wheat, enough to feed a large family for at least a year.

This abundance was scarcely inferior to the plenty provided by acorns. Though threshing and hulling may at first have seemed awkward and unpleasant, in the long run, they probably proved less tiring than hulling and leaching acorns. Once the change to grain had been made, why go back? The forward-thinking wishes of the leaders of the new group may have been fulfilled. Here was a new way of life, not dependent on the old ones back up among the trees.

For several generations, this new village would have prospered and grown. It might have experienced want in a bad wheat year, but the stuff was so abundant that no one would have starved. Eventually, a group of young ones would have arisen who had just the same complaint as their forebears: Everything is so settled here. We haven’t got a chance. We want something different.

But when they looked out they saw neither oak grove nor hills alive with grass. They saw lowlands that were well watered with rivers and seasonal streams, but with sparser vegetation and with nothing that could serve as a staple food.

Most of them sighed. But a bright one pointed to a stream, shining in the afternoon sun, and said, “Look, we’ll take grain with us. It will sprout and bear fruit in a year. Until it’s ready, we will trade the produce of our herds for bread. And if we plant near the water, doubtless we will have a good harvest.”

And they did. Not only did they have a good harvest, they had a bumper crop. Never had so much wheat come from so small an area. They were encouraged. They chose the best and fattest seeds to plant for the next year’s crop, and again the harvest was beyond their wildest dreams. Soon, they had a village as large as the one they’d come from, gathering the wheat from one-tenth the acreage. Everyone was well fed.

But there were two unanticipated consequences. For the first time, land became valuable. The whole village’s food was grown on a comparatively small parcel of land where the water table was high. (When archaeologists look at the seed caches left by such villages, they often find wheat seed mixed with sedge and other marsh grass seeds, so close did they plant wheat to the water.) And for the first time, if the water failed or flooded, the crop grew poorly or not at all, and people starved.

This was a new and not a pleasant experience. The brightest and the sweetest said, “We must see to it that there will never be a failure, and if there is, each must have at least enough to live. For this reason, I must manage the land.” The most unscrupulous said, “We must see to it that if there is too little for all, we, at least, will have enough. We must possess this land.”

For the first time, a small number of people acquired control over the land that produced the food for everyone. This too was likely not a pleasant experience, especially for those who were less well provided for in times of famine.

The brightest of these, driven by need, thought, “Look, we can go out onto the plains where streams run a long ways. True, it is hotter and more exposed there, but we will dig channels from the stream out into the land. This way, the water will be spread far wider, and we will be able to grow so much that everyone will have enough to eat again.”

Notice the “again.” This is perhaps the first time in human history that a people looked back in longing to a previous age of plenty.

But on the flats, all went well at first. A great work of digging and cultivating was established. Improved grains that had been developed in their native villages were applied to a vast area and produced immense amounts of food. Soon, they could thumb their noses at the floodplain cultivators. Where the ancestral village might have been able to support at most a couple hundred people, the irrigators could support several thousand in one town.

In the ancient Near East, this was the root of the great civilizations of the plains: the Assyrians, Babylonians, Akkadians, and Sumerians. They raised heretofore unimagined amounts of food on a very small amount of land. Perhaps 10 percent of the land supported all of the people. Towns turned to walled cities, and pyramids rose. The best land fell into the hands of a few people, and these people—for the common good or for their own good, and usually for both—arranged the lives and possibilities of the rest. A third of the food came from land belonging to only 1 percent of the people. There was little choice for the discontented, since without these food resources, they would die.

The same two consequences—ownership and starvation—quickly visited the cities of the plains. There was a third as well: salt. It turns out that when flatlands that have no natural route for drainage are irrigated, sooner or later salts concentrate in the soils. When they come near the surface, they poison wheat. Indeed, later food production in all of these early cultures was skewed toward barley, which is more salt tolerant.

Perhaps in this situation, the least well fed would have looked back in longing to the lands of their forefathers, now practically lost in legend, when they had freely eaten the fruit of the trees. But it was too late to go back.

For many generations, the oak-wood dwellers had been degrading their own lands. When they cut oaks for firewood or to build their houses, it was hard for the trees to get a fresh start, because goats would eat the tender shoots. Furthermore, the more successful the people and their grain-eating neighbors became, the more the population grew and the more they would need oak for its wood, not its food. After all, they could trade the wood for grain and become more modern.

Now the cities of the plains made large demands on the upland dwellers for wood. They had houses, temples, and walls to build. They needed charcoal to forge first bronze, then iron, and to make pottery and glass. They had a lot of interior space to heat. Furthermore, they could enforce their demands with weapons that a culture of gatherers could not resist.

Today, in regions of the Zagros Mountains in Iran, where ten thousand years ago people gathered in a few weeks all the food they needed for the year, people eke out a hard and bare living farming wheat and barley. They labor a hundred times as hard for fewer calories than did their primitive ancestors. The hills are bare; the land eroded. The oak trees are almost all gone.

The Place That Waits for Me

Only a single constellation of balanocultures survived into historical times, the cultures of Native California. These were still intact when the first Europeans arrived in the late eighteenth century, and remnants of them survive to this day. There was nothing particularly notable or memorable about these cultures—nothing at least most people would call memorable. They had none of the fierce nobility of the Plains tribes, the clear intelligence of the Cherokee, or the civilized life of the Hopi. The first Europeans to arrive described the natives as sleek, well fed, and indolent. “Diggers” the Gold Rush immigrants called them, noting that they were adept at finding edible and medicinal roots. The immigrants found this disgusting, although it was in every case a part of the broad-spectrum gathering habits that made the natives far better adapted to life in that land than were the invaders. With few exceptions, the tribes welcomed the invading Europeans, and without exception they were overwhelmed.

Only a single constellation of balanocultures survived into historical times, the cultures of Native California. These were still intact when the first Europeans arrived in the late eighteenth century, and remnants of them survive to this day. There was nothing particularly notable or memorable about these cultures—nothing at least most people would call memorable. They had none of the fierce nobility of the Plains tribes, the clear intelligence of the Cherokee, or the civilized life of the Hopi. The first Europeans to arrive described the natives as sleek, well fed, and indolent. “Diggers” the Gold Rush immigrants called them, noting that they were adept at finding edible and medicinal roots. The immigrants found this disgusting, although it was in every case a part of the broad-spectrum gathering habits that made the natives far better adapted to life in that land than were the invaders. With few exceptions, the tribes welcomed the invading Europeans, and without exception they were overwhelmed.

Yet there is one remarkable fact about them: There were so many of them. Within the boundaries of present-day California, there were at least one hundred separate tribes, each with its own language (or at least dialect), stories, religion, customs, and territory. Each territory was a classic vertical economy, with mountain, foothills, and watered valleys, each zone contributing to the tribe’s subsistence. The boundaries were usually defined by the watershed of a given river. Tribelets—often groups of a few extended families—lived in small villages by the rivers and traveled up-country for hunting and gathering. Most tribes gathered all the tribelets together at least once a year for a ceremony of world renewal, but the dances, songs, costumes, and settings of these ceremonies were widely different from tribe to tribe.

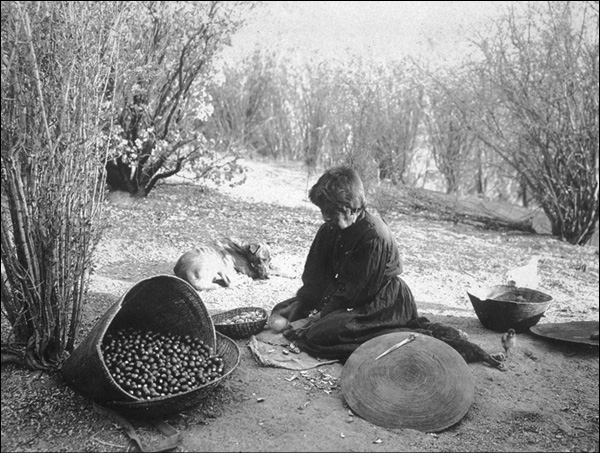

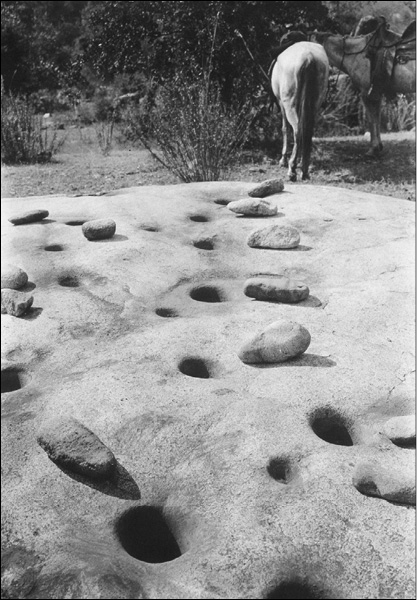

Virtually every tribe, however, had one thing in common: acorns. Every territory contained oaks in its foothill and/or mountain section, and the acorns gathered were a central feature of the tribe’s livelihood. Other gathered foods varied widely—from salmon in the north to pinole nuts in the south—but acorn was everywhere a staple food. It is even thought that the presence of sufficient acorns within a given area was what allowed a tribe to settle down and become a tribe, that is, that the distribution of oak trees determined the total number of tribes. Early European travelers came to recognize how close they were to a village in the middle of any given day by the continual dull booming thump of women driving mortars into pestles to grind the acorn meat into meal.

Throughout California, the annual autumn acorn gathering was the year’s main event. Often, the whole tribe would go together into the hills and establish an acorn camp near the grove that was theirs by right and custom. Among the Cahuilla of southern California, a family called its holding Meki’i’wah, which means “the place that waits for me.”

The rituals for claiming a tree were various but everywhere polite. Among the Wintu of northern California, if you found a tree that you thought no one else had found, you could lean sticks all around it to signify your right to pick its acorns. On the other hand, if you had seen this tree before but failed to mark it, you could remove one of the other person’s sticks and claim a part of the tree for yourself, but you would have to bargain with the person to pay for your claim. In any case, if a tree were particularly large, you would not likely be so greedy as to claim the whole thing. Instead, you would lean your stick against the tree to mark a single branch.

When the tribe arrived at the acorn camp, they would set out in parties to their various trees and groves. The men would climb the trees to shake off the acorns, while the women and children would gather both the freshly fallen and those that were already on the ground. (The former made the best soup, smooth and white, while the latter made a darker and less desirable soup.) To strip two trees in a day was thought to be fast work, since a large tree might contain three hundred to five hundred pounds of acorns.

Not everyone spent all day gathering. The men might hunt acorn-eating animals that were attracted to the groves for the same reason as the humans. Others would gather wood for firewood or for paddles and handles. A shaman would collect certain oak galls, which were powdered and used against eye infections and to help heal wounds. Bark was gathered to use as a fuel and to boil to extract a black dye used in basketry. Leaves were taken to be dried, shredded, and used as tinder.

Some tribes started shucking acorns right at the base of the tree, others carried the day’s haul back to the acorn camp. There, the adults would sit around the fire, cracking shells and extracting the meat. Some did it with their teeth, crunching the shells first lengthwise and then crosswise; others used rocks. Other acorns had only their caps removed; they were taken intact back to the village for long-term storage. Some young women strung whole acorns into necklaces, and children played games of jacks with them or did juggling tricks.

For two or three weeks, the group stayed at the acorn camp. After the first day, at least one woman would stay in the camp to guard the acorns that had been spread out to dry. Her job was to turn them so that they dried thoroughly and to ward off predators. Although she did no collecting, she was allotted a share of the harvest.

A California native woman shucking acorns (C. H. Merriam, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

It was a hard walk back to the main village, since each family had to carry hundreds of pounds of acorns, but at least it was mainly downhill. At the village, some of the acorns were stored in raised bins woven out of stems and vines and coated with pine pitch or lined with bay laurel leaves to discourage marauders. Others were buried whole in a bark-lined pit or underwater. After the destruction of the Native cultures, for decades farmers working the low ground—just as they did in the Northeast—would still plow up caches of these water-buried acorns, which were still sound and edible after half a century.

Communal mortars and pestles in a large rock (C. H. Merriam, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Back home, life returned to its daily round. Everyday by midday, pestles boomed in mortars as the women ground the acorns into meal. Usually, a woman had several mortars and pestles. Some mortars were hollowed out in the bedrock, and some she could carry with her. She made these by heating the stone, then chipping it away with a sharp rock. Young women did most of the grinding, while the older women sifted the meal and divided it into different kinds by size—some for soup, some for mush, some for bread. (You were not supposed to sing love songs while grinding, because the words might cause the pestles to break.) In most tribes, only a woman or her daughters had the right to use her mortars and pestles. When she died, one of her mortars would be broken and buried upside down.

After grinding the acorns, the women leached the meal, usually in a depression made in sand and lined with leaves to keep the sand from mixing with the meal. Cool or warm water was poured over the meal until the bitter tannins were washed out. The process took two hours or more. With certain acorns, especially those from the valley oak, Quercus lobata, the Wintu women would soak the leached acorn meal in still water until a mold began to develop. The mold was said to make valley oak acorn bread particularly tasty.

A few tribes leached whole acorns to eat whole, but almost all of them made their acorns into soup, mush, or bread. The main difference between the three was the consistency of the meal mixture, and the final product depended on a woman’s skill with rocks and water. To make soup, a small amount of coarser meal went into a basket with water. Hot rocks were lowered in to heat and thicken the soup. With more and finer meal, the same process yielded a jellied mush that, if allowed to set, could be cut into squares and distributed like a flan or Jell-O. Alternatively, it could be eaten warm, and during festivals it often was; people dipped their hands into a common pot and licked them clean. Acorn bread was often a woman’s finest dish, since it involved getting just the right consistency of mush, then laying it on a bed of fern above hot rocks, then covering the mush with flavorings and with more fern and finally earth. The bread would cook overnight and be ready in the morning. Depending on the flavorings that had been added, it could keep for months.

In 1907, C. H. Merriam of National Geographic attended a funeral that was held in a round house in Tuolumne County, California. He reported that to feed the guests, the cooks began preparing several days prior to the feast, leaching acorn in four 5-foot diameter leaching pits. When the festival began, they had ready fifty huge baskets, each containing one to two bushels of fresh acorn mush. They had also prepared fifty loaves of acorn bread. He estimated that the guests at the two-day feast consumed upward of a ton of acorn.

The amount itself is staggering, but what is more wonderful to me is that this was nothing but a late—perhaps the last—example of a tradition that extended throughout the length and breadth of California, virtually unchanged, for more than five thousand years. The great thing about balanoculture is that it allowed the slow maturation, in place, of at least one hundred separate cultures. Protected by sea and high mountains and deserts from alien encroachment and defended from themselves by a temperate climate that made it unnecessary to deplete the oaks for fuel, the California cultures proliferated.

Were they great cultures? By our standards, they were not. They left no great monuments. They could not defend themselves from the invaders who at last arrived. In a sense they were repulsively bland, as the Gold Rush prospectors found them, though to be honest, it was the prospectors themselves who should have gone by the perjorative “Diggers.” Their digging destroyed whole landscapes in pursuit of gold, while the natives lived lightly and without harm on the land.

Nevertheless, even A. L. Kroeber, the great anthropologist who devoted his life to the study of the California Indians and to gathering all available information about their lives, agreed in the end with the historian Arnold Toynbee, that the Native Californians could not have had great cultures, because their wishes met with too little resistance.

I think Kroeber made a category mistake. The cultures of the California Indians were not greater or less great than other cultures. They were something different altogether.

In 1911 a lone man was caught raiding a chicken coop in northern California. He was naked, long haired, and carried stone tools. They threw an old coat over him and called the University of California. Kroeber and his wife, Theodora, appeared to take the man to live with them in Berkeley. His name was Ishi, and so far as anyone could tell, he was the last living member of his tribe, the Yahi.

Theodora Kroeber’s book about Ishi’s life with them is one of the classics of California literature. In it, among many other things, she recounts some of the stories and legends that Ishi told them.

One tale concerns an old woman who tells her daughter, “There is a strong, good-looking young man. I want you to go and marry him.” The daughter refuses, even though the man is interested in her, until her mother threatens to throw her out of the house. “How will we live,” the mother says, “unless this man comes to hunt for us? I am getting too old.” The daughter consents and seeks out the man. They then play the courtship game in which she again and again invites and rebuffs him, until finally she agrees to marry. “But listen,” she says to him, “you have to go and ask my mother’s consent. Maybe she won’t want you in our family.” You can hear the laughter of the Yahi people who listened to this story around the fire for perhaps several thousand years. And you and I laugh just as much, with just the same understanding that this is the way that human relations are. As a modern girl once put it, “He came after me. I ran and I ran, until I caught him.”

The mother in the story, of course, is overjoyed. She describes the life that will blossom among them as though she were weaving it on a loom: “He will come to live with us and bring us meat while we cook him acorns. Then babies will be born, and you will make your own house, and I will come to you. You will rejoice to see me coming with a basket full of acorns on my back.”

It is hard to conceive of a story that better expresses the wishes and the understandings of everyday life. Before and beyond all struggle, what every human seeks is the peace of such joys as lovers, parents, children, and friends experience. Nothing beyond.

The first aliens to penetrate the California balanocultures might never have eaten an acorn. But they came in boots tanned with oak bark, eating pigs fed on acorns, carrying iron weapons forged in smithies fueled by oak charcoal, writing with ink made from oak galls, and riding across the seas in oak ships. They were restless seekers, like so many Europeans of the time, looking for a new life, new wealth, new worlds.

The newcomers and the natives shared one thing: Both flourished on account of oak.