Shifter

The black and white give it away before Fat Reggie even gets back home. He knows they’s there for him, but dang if he knows why. Still, driving a black and white into the hood ain’t no way to track someone. Might as well leave the sirens blaring—everyone knows they’s there.

And that’s just fine with Fat Reggie.

He ducks hisself into the stairwell of that fortress white people call The Projects—ain’t no one goes in unless they belong there. The stairwell smells a piss and there be thick stuff dribbling down the walls, all thick like snot.

When Fat Reggie first moved to the hood, old Ms. Baxter told him some folks sends their kids into the stairwell to take a pee. The smell keeps the hos from turning tricks there. Fat Reggie understands that—he don’t want to stay in there any longer than he got to.

He pulls a pen and a pad a paper out from his backpack. He touches the tip of the pen to his tongue. He starts to write. As he writes Fat Reggie starts to change—with a few words he gives himself a tumor on the right side a his face. Makes it big and purple with veins all sticking out. Makes it squish his eye shut.

While he’s at it, Fat Reggie writes off about forty pounds of fat. Writes it clean out of existence. Doesn’t quite go so far as to make hisself Thin Reggie, but he feels the skin round his midsection go slack. Then he tightens up the skin to make it fit right.

After that he changes his black t-shirt for a red one he keeps in his backpack. When he’s done, ain’t no one going to recognize Fat Reggie, that’s for sure.

He walks right down the hall, past old Ms. Baxter’s place, and marches right in through the door of the pit he and his dad share.

Sure enough, there be two Uniforms and a fine ponytailed blonde number wearing a tan trench, sitting there with Reggie’s dad, waiting for him. “Hi,” he says.

The two Uniforms, they look on edge. One of them with more muscle than brains practically jumps when Reggie bursts through the door.

The blondie looks at Reggie, looks at his tumor, and turns to the muscleheaded cop. “This is him?”

Musclehead looks like someone stole his Christmas. Mutters something that sounds like an apology.

Blondie struggles to her feet—everyone struggles to get out a their butt-eating couch. She wipes her trench like someone sneezed on it. To Reggie’s dad, she says, “I’m sorry we bothered you, Mr. Williams.”

Reggie’s dad don’t bother getting up. “I told you wasn’t Reggie. Maybe you should start trusting people, stead a thinking you right all the time.”

The blonde looks around the room, examining the walls. Reggie knows what she’s looking for, but she ain’t going to find it. All the walls got on them is a bunch of dings and places where the paint been chipped off. Other than that, they’s barren.

She says, “In the future, you should think about getting some pictures of you and your son. We could have cleared this up a long time ago.”

Reggie’s dad grunts, but he don’t say nothing. Never going to happen. No pictures—that’s the first rule Reggie and his dad live by.

“Again, I’m sorry we bothered you.” She nods to Reggie, nods to the officers, and the three of them, they head for the door. Her ponytail dances as she moves.

As she walks past Reggie, he can’t help himself. He grabs her wrist, right where the tan trench ends. Her skin is warm and soft. She tries to pull away, but she looks at Reggie, at his tumor, and pity fills her face—especially her deep-blue eyes.

From feeling the bones in her wrist and the way her muscles move, Reggie knows she’s got an athlete’s body under that coat. Even though she’s about five inches shorter than Reggie, he knows in a fight he’ll lose for sure.

Reggie lets go of her wrist and does his best to look sorry. “Don’t mean nothing,” he says. “I just wants to know what’s going on.”

She clears her throat. “I’m Detective Palmer.” She nods at the Uniforms. “These are officers Burke—” (the muscle) “—and Routh. We got a report earlier tonight that you’d been involved in an incident.”

“An incident? Where?”

“Well,” she says, “it obviously wasn’t you, so that doesn’t matter.”

Shoot. He’d so hoped to learn something. Find out who’d got wise to him.

Blondie Palmer walks past the officers and the three of them head down the hallway past Ms. Baxter’s. As they go Reggie leans out into the hallway to holler, “’Bye now,” but really he’s watching Detective Palmer—the way she walks.

When Reggie turns round, he’s staring right into the cold-dark eyes of his father. Reggie’s dad bounce-walks him straight back until Reggie’s pinned between the door and the beater shirt covering the rolls a fat currently making up his dad’s body.

“What did you do?” his dad says.

“Shoot, man, I don’t know. Been over on King Street, asking after Georgie. Someone got wise.”

Reggie’s dad pokes a thick finger in Reggie’s chest. “I told you, leave that be.” And he pokes Reggie’s chest again, driving the point home.

Reggie rubs his chest where the poke left its ache. “Dang, old man. It’s like you don’t care none.”

“Georgie’s the reason we living in this hellhole. I spent all the time on him he’s going to get. Somebody seen you, figured out who you are and where you live. And that sent the cops to me. And that ain’t never going to happen again. We clear on that, boy?”

By that, Reggie knows his dad’s talking about appearance. He’s been Reggie for a long time; now he needs to become someone new.

Reggie slips past his dad, into his room, where he flops down on his mattress. It’s an old mattress with holes in the top. Sometimes when Reggie sleeps, the tops of the springs come through the holes, jabbing his back and legs.

But it’s under the mattress that Reggie keeps his treasure.

Two binders full a paper.

Each one a different person Reggie’s been.

He flips through them, remembering.

This one’s a crusty old Asian guy Reggie used to be when he and Georgie drove taxis day in and day out out by the airport.

And this here is a musclehead like that officer, Burke. Reggie used that one when he lived on his own out by the beach.

And this page is one a Reggie’s favorites—a teenage cheerleader. Reggie used her when he and Georgie and their father went living the high life over east a High Street.

Yeah, she’s one of Reggie’s favorites. He loved cheering for the team before a big game.

Thinking about being a cheerleader starts Reggie thinking about Detective Palmer, the way she moves.

Shoot. Detective Palmer, she don’t move. She flows.

And that’s something Reggie thinks he really ought to try.

He pulls off a piece of paper and begins writing a new body for himself. As he writes, the deep chocolate color of his skin starts to fade. The stiff, short, bristly hair atop his head goes away and new smooth hair, the color a hay before harvest, grows out in its place. He makes the hair long enough to pull back into a nice ponytail, but leaves it loose so that, as he writes, he got to push the hair back over his ear to keep it out of his eyes.

The air fills with cracks and pops as his backbone shrinks. His ribcage gets smaller, leaving his skin hanging all flopsy-like.

He writes away the rest a the fat he left on his self out in the stairwell. Before tightening up the skin Reggie adds just a bit a that fat back, giving himself nice round breasts. It’s been a while since Reggie last had ’em, and already he knows that nice, smooth walk he wants will have a bounce in it for awhile while he adjusts to this new body.

He keeps writing, putting in every detail he can remember ’bout Detective Palmer.

When he thinks he’s getting close, Reggie checks himself out in the warped full-length mirror mounted on the back a his door. When he stands up, the baggy pants he been wearing, they fall right off.

He looks pretty funny in them man-briefs with a body that ain’t got no man-parts.

Reggie makes a few adjustments, raising the butt, slimming the waist, and when he’s finally happy he turns over that sheet a paper and tries to figure out what to write here.

That first side, that’s easy. That’s all physical.

This here side, it’s personality.

The first line, that’s going to be his new name. Reggie takes a while thinking about this, because he’s got to get it right. From now on, when people call this, he’s going to turn round to see what they want.

Reggie starts by asking himself: What do I want with this here me?

And the answer comes, just as he knew it would: I wants to find Georgie.

Well, shoot. He can’t go ’round looking like no blondie white girl asking questions about her brother—not in the neighborhoods Georgie’s likely to go.

Unless …

Reggie gets a truly evil idea. At the top of the page he writes: My name is Detective Trisha Palmer.

The “Trisha,” that’s just a guess. But Reggie fills in the rest a that page, making up all the details that he thinks would make for a good detective.

First off, she wouldn’t go thinking of herself as “he.”

And she’d likely be educated. A college degree.

Raised in a middle-class family. She still loves her father enough to be a daddy’s girl.

Her favorite colors are pink and especially blue, because of the way it matches her eyes.

As the paper fills with text, the scratches that were once so recognizable as Reggie’s writing smooth out, becoming a beautiful, flowing cursive—the handwriting of a girl so detail-oriented that, in third grade, she spent hours practicing every character, above and beyond what the teacher required, until each letter was perfect.

The identity that once masked Reggie melts away until

All that was left was Trisha Palmer.

And she was exhausted. These changes always took so much out of her. It would be several hours before she’d be ready to even write in small changes.

She hoped what Reggie had done would be good enough.

She gazed around the room, seeing it with fresh eyes. The dingy mattress, uncomfortable against her tush, stained with dark reds and yellows from years of use before she and her father had even moved in. Sparsely decorated walls—unframed posters of sports teams, mostly, with corners curling where the tape holding them down had dried and cracked.

The one little table in the corner, on which lay the only possession Trisha would actually miss: a glass football, engraved with Grover Cleveland High School—State Champions 2003. The year she’d been a cheerleader and Georgie (then called Tyson) had been the star running back on the team.

Georgie’s trophy.

The only piece of him she still had left.

No way she could take that with her, but her father knew how important it was to her. He’d keep it safe.

She stood up, examining herself in the mirror. Overall, she felt pleased with the result. Oh, she was far from perfect. Far from it. But with a few written words—after she’d rested—she could fix the problem areas.

Now … time to find some decent clothes.

Trisha pulled on Reggie’s old closet door. It refused to open all the way and, when she tried to force it, the spring-loaded pin holding it in place snapped and the door fell.

She yelped and tried to catch it, but it was no use. The closet door slammed into the wall, leaving a terrific gash where its corner carved through the wallboard.

“The hell?” her father called from the other room, and within a few moments he burst through the door. When he saw her, his eyes practically bulged from his head.

“Hi, Daddy,” she said. “My name is Trisha.”

“Hell no.” Her father waddled forward, trying to intimidate her. “You ain’t doing this to me.”

She held her ground, but looked down, suddenly embarrassed by herself. She—Reggie—had broken the second rule that had kept them safe for so many years: Never duplicate someone completely. In the past she’d always used pieces of people—eyes from a waitress who’d been kind to her; the chin of an actor she admired. This was the first time she’d copied someone whole cloth.

Daddy was right to be angry. They’d been through a lot together, she and her father. The sacrifices he’d made for her … some of them were things she couldn’t imagine doing herself. She’d never loved anyone that much.

Except maybe Georgie.

Georgie had made it clear that he didn’t like the way they were living—at the time they’d been a refugee family from Cambodia. She guessed they’d stayed too long in the ritzy part of the city before that. Georgie had gotten too used to wealth; the transition to poverty had been too hard on him.

So, one day, without even saying “goodbye,” Georgie disappeared, taking the balance in their savings account with him. Seventy years of savings among the three of them—sixty years for Daddy alone before that.

Living the easy life had been Daddy’s idea. A way to reward his children for years of hard work. If he’d known what it would do to Georgie, her father would never have done it. And now her father seemed to despise Georgie.

And she …

She couldn’t forget her twin. She never would. She had to at least know that he was okay.

No matter what.

But her father was right—it was unfair of her to do this to him. She would never bring her family back together again. She knew that.

No, finding her brother was something she had to do for her own peace of mind.

Trisha felt stubbornness creep into her face as she raised her head. “You’re right, Daddy. I won’t do this to you.”

“Damn right.”

“But I will do this. For me.”

Her father started to shake his head, but she cut him off with a glance before he could speak.

Fierce determination. That’s what defined Trisha Palmer.

She’d said so right on that piece of paper that now made the latest page in her binder.

Her father cursed her several times, but he knew she’d made up her mind. Finally he could do nothing more that wrap his big, heavy arms around her and hold her close.

He hadn’t showered in days, judging from the smell. At first that bothered her. And then she realized how tightly he held her, the way it made it hard for her to breathe.

And she knew. He wasn’t wishing her luck. He was saying goodbye.

Tears began swelling in her eyes, and she returned the hug as hard as she could.

“Daddy, I—”

“Hush now,” he said, stroking the back of her head. “I knew this day was coming. Got a little cash-money saved away.”

“No. No, I couldn’t. You need it more than—”

He laughed—a great belly shaker that nearly lifted her off the ground every time his stomach shook.

“Don’t be a fool, child. Look at you. You think Reggie got any clothes going to fit you right? And I will not have my baby living on the street. Not when I can do something about it, no sir.”

The tears came, stronger than before. Her daddy wiped them away with a thick, clumsy thumb. “Hush,” he said. “Now you come with me. I think I got some leftover clothes from a few years back when I was a stripper. Nothing showy, mind you. Got rid a all them stage clothes. Sides, any man goes looking after my baby girl with wolf’s eyes, I going to take him out.”

Trisha waited until four-thirty the next morning before leaving the projects. By then it was quiet. Even the dealers and the prostitutes had stumbled home. Anyone still awake would at least be tired—too tired to pay much attention to a white girl walking alone down one of the most dangerous streets in the city.

She hoped.

She took a quick glance back and forth down the empty hallway. Grime covered everything. How had she managed to live here this long?

She ducked back inside her father’s apartment and took one final inventory of herself before venturing out. She double-checked the drawstring on her sweats and made sure the roll of cash her father had given her still rested firmly in the bottom of her sweatpants pocket. Then she adjusted (yet again) the strap on the Victoria’s Secret one-size-too-big bra Daddy had found among his “leftovers.” How annoying. A replacement bra would be among the first things Trisha would buy—right after she bought shoes. For now she had to make do with Reggie’s tennies. Her feet slid around inside them with every step she took. It would be impossible to run. She offered a little prayer, asking that running wouldn’t be necessary.

The fatigue from her transformation still wore deep on her. She felt it in her bones. Priority one would be getting to the business district—somewhere she didn’t stick out so much—to find a hotel. Trisha felt like she could sleep for days.

She checked her ponytail, making sure it was securely held in place, before pulling the black hoodie up around her head.

Her father caught the hood halfway up and turned Trisha around. She saw the look in his eyes and felt the tears begin to well up again. She fought them back, still tasting the salt from her last bout of weeping. Not again. Not this time.

She’d done this before. As a bodybuilder at the beach, she’d been on her own. She knew she could do it.

But this time felt different.

Before, it had been … well, it had been practice. She’d had to know if she was ready to face the world alone.

And she had been. She’d come through it just fine.

This time …

She finished the thought aloud. “This time it’s for real, isn’t it?”

Her father held her face firmly between his thick, meaty palms and touched his forehead to hers. She felt the grit of dried sweat on his skin. She felt the heat of his body. She felt the reality of him flood her head—

And she saw.

Saw him as a child. A little boy in shorts chasing after a dog named Ryan.

Saw him as a Chinese man slaving away on the railroad lines.

Saw him as a nurse in the hospitals during World War One, tending to the injured.

Over and over again, she saw him in all his incarnations—and especially strong came the vision of her father as a young woman, deciding the time was right to write a child into his life—and then the surprise and joy that came when he discovered he was having not just one child, but two.

And then the disappointment and anger of her father as a middle-aged fry cook, as Georgie rattled off the list of complaints of every way their father had “wronged” him, when all along their father had been trying to do the best he could for his children.

As the vision faded, Trisha heard her father—her daddy—say one last thing: “I am now and always have been proud of you. Don’t worry none about me. When I’m ready to move on, I’ll come find you.”

Trisha shifted her weight back and forth, trying to find a comfortable spot on the hard wooden bench in the booth at Dezzi’s Coffee. The bitter aroma of roasting beans filled the air. She took a sip of Dezzi’s Special Blend and grimaced as the flavor bit back and the heat numbed the roof of her mouth.

Dezzi’s Coffee sat directly opposite the Second Precinct building. And Trisha sat there, in the open, wearing her new tan trench coat, white blouse and black pants, daring anyone—no, hoping someone—would see her and recognize her as Detective Palmer.

This was among the stupider things she’d tried.

Trisha wondered if anyone had ever tried looking up all the Palmers in the greater metropolitan area. She’d spent weeks doing just that. Weeks. Camping out at their residences. Smiling and saying “Hello” to neighbors. Looking for any sign of recognition.

Pointless.

Detective Palmer, naturally, wasn’t listed in any of the phone directories.

As she sipped her coffee Trisha cast glances across the street at the police station, hoping to catch even a glimpse of blonde hair.

Actually walking into the station was more foolish than Trisha dared try. If she’d gone in while the real Detective Palmer was there—if they actually ran into each other … There’s no possible way to explain that.

She’d just finished her second cup and was about to give up and move on to the next station house when a short little woman in a beige skirt with black hair waved at her.

“Janet! Hi!” the woman said.

Trisha had a Who? Me? moment before the realization struck—Janet. Detective Palmer’s first name was Janet.

The excitement of the moment left Trisha as quickly as it had arrived. Crap. Someone thinks I’m Detective Palmer. Now what do I do?

“Hey,” Trisha said. “Long time.”

The woman approached the booth with a steaming cup nestled between both hands. Trisha hoped Detective Palmer and the woman didn’t know each other well.

“No kidding,” the woman said. “What are you doing over here? Don’t tell me you and Hurley are seeing each other again?”

Trisha did her best to look guilty—not that difficult considering the circumstances. “I cannot tell a lie,” she said.

A look crossed the little woman’s face that seemed to say, You can do better than Hurley. She seemed to realize what she’d done because she fumbled with the cup for a moment and then changed the conversation completely.

“You ever get what you needed on that Weevil’s Club case?”

Weevil’s Club? That was over on King Street—the neighborhood Reggie had been in, asking questions about Georgie. The neighborhood where someone had blown Reggie’s disguise and made this whole stint as Trisha Palmer necessary.

Now that was a lead.

“Not yet,” Trisha told the woman. “But I have a hunch something’s about to break open.”

Trisha couldn’t imagine a darker place than The Weevil’s Club—and it was still the middle of the day. The club itself was in the basement of an old brick three-story. Uneven stairs led down through a shadowy doorway. Inside, yes, the lights were dim, but, on top of that, mud seemed to coat the outside of every gutter-level window. The oppressive music blaring through the speakers overhead drowned out any conversation.

Weevil himself, a tattooed giant of a man, washed glasses behind the bar with a rag that seriously needed replacement.

Even though the city had long ago passed a ban on indoor smoking, Weevil’s stunk with the combination of the fresh smoke that clung to its patrons and the rancid odor that had permeated the walls before the ban went into effect.

Weevil saw her and glared. Trisha fought back a shudder.

He motioned with his head toward a doorway next to the bar. Trisha followed him through it.

Weevil’s office was nicer than the club itself, but that wasn’t saying much. The door muffled the music, except for the ever-present repetitive throb of the bass line. Bare energy-efficient light bulbs overhead, screwed into dingy sockets, cast a fluorescent-blue haze on mangy carpeting and wood-paneled walls.

A pine-scented candle burned away on Weevil’s desk, but even that couldn’t cut the rancid smoke flavor of the air by much.

Weevil leaned against a cluttered desk with arms folded. “You got it?” he said.

Trisha had done it again—obviously she was supposed to know what he was talking about. Time to fake it again.

“No,” she said. “Not yet.”

Weevil turned his back on her. “Then we got nothing to say, Detective. You can see yourself out.”

Trisha stepped forward, feeling the fierce determination swelling in her chest. The police had come for her, back before her change. And something had happened here—the same neighborhood she’d been in, asking about Georgie. She was pretty sure Weevil knew what connected those two things.

But what could she say? Hi. I’m not really Detective Palmer. I used to be a black kid. He’d never believe it.

But she had to say something. He had already gathered a few papers from a filing cabinet and was now herding her toward the door, back into the club where the music would drown out anything she tried to say.

She opened her mouth and the words came out before she knew what they were. “Fat Reggie,” she said.

Weevil froze. An evil little smile crept into the corners of his mouth.

“You finally tracked him down, eh? What did that little bastard have to say for himself?”

“Said he was innocent.”

“Naturally.”

“I believe him,” Trisha said.

The little muscle just below Weevil’s eye began to twitch. “You look here, Detective. I don’t care what you think of me. I don’t. You get your shit together and get your search warrant. You come back here with that and I’ll play nice—give you a tour of the whole joint. But that fat little runt stole my football trophy from me. Got half a dozen witnesses say so—including one of The City’s Finest. He stole it, and I want it back.”

Trisha’s mind churned. Witnesses? As Reggie she’d been up and down this street, asking about her brother. It was the kind of neighborhood that attracted Georgie—though she couldn’t pretend to understand why—but she’d never stepped foot in Weevil’s until that afternoon.

And his trophy? His?

She took a step toward Weevil, closing the space between them, and placed her hand on the rough stubble of his face.

“Look, lady, I—”

Before he could pull away she went up on her tiptoes and touched her head to his.

If she was wrong and this wasn’t Georgie, she’d probably just invited him to rape her.

Weevil didn’t resist her. He closed his eyes, allowing the essence of himself to flow between them.

And she saw.

Saw Georgie standing up to their mother as a fry cook, petulant and eager to face the world on his own terms. Felt the oppression Georgie believed their mother placed on him.

Saw him change himself into the appearance of a bank teller at the local branch—he’d been watching her for weeks, flirting with her for days. A silly girl who’d accidentally mentioned that the Facebook password she’d just given him was the same password she used everywhere so that she never had to remember anything.

Saw him use the girl’s appearance to access their father’s savings—their family’s savings—draining the whole account.

Saw him as a forty-year-old office worker, removing her heels to relieve her sore feet, dreaming of the end of the workday where she would lavish a younger admirer with the finest wine, dinner at a four-star restaurant, and a passionate night in a luxury suite.

Saw him as a teenage boy, out on the street, wondering what had happened to all of his money.

Saw that boy admiring Weevil—Weevil’s presence, his command of the neighborhood. Saw him sneaking after Weevil late at night when Weevil resupplied his dealers and paid off corrupt government officials.

Saw that boy kill Weevil. Brutally. Slashing Weevil’s throat and enjoying the feel of the blood splattering that boy’s face.

Saw that boy become Weevil. Writing himself into Weevil’s world. Taking over the drug operation. Expanding it. With a fierce determination to conquer—to be free forever from the oppression of poverty. To rule over his domain.

No matter the cost.

Trisha tried to force herself away, but the vision kept coming. Weevil, strangling a pimp. Taking over the prostitution in this part of the city. Weevil, hiring thugs from the worst of the city’s gangs. Weevil, threatening the son of a city councilwoman if she didn’t change her vote on upcoming ordinances.

Weevil, staring down the real Detective Janet Palmer, daring her to come at him with everything she had. Knowing that she would. And not caring because he knew he could get away with it.

The horror of it all rocked Trisha to the core. Her brother had done terrible, terrible things.

And then she saw Weevil, getting word of some punk-ass fat kid traipsing up and down King Street, asking if anybody had seen his brother Georgie.

And Weevil had made one last transformation—just for one day. Just long enough to be ready to change back.

Weevil as Fat Reggie, bursting from the office behind the bar, holding tight to a water bottle nestled in the folds of his jacket so no one could see, dashing out into the cool evening, into the crowds, and into a side alley where he wrote himself back into Weevil and called the cops to report a robbery at his club.

The vision broke and Trisha pulled away only to see a look of smug self-satisfaction on her brother’s face.

“You came,” he said. “I knew you’d get my message.”

Goosebumps prickled along Trisha’s arms, and she pulled her coat tightly closed around her to stave off the chill. Weevil didn’t keep his office that cold, but everything she’d just witnessed about the way her brother spent the last several months made her shiver.

She sank back into the soft leather of an oversized chair. She supposed it was comfortable, but right now Trisha didn’t think she’d ever be comfortable again.

The only thing she’d wanted—her brother—had been found, and with that, and with the discovery of who he really was, her fierce determination faded away and left her utterly alone.

The door opened, briefly inviting that dreadful music, and slammed again as Weevil returned with a tumbler full of some kind of beer that looked and smelled like piss.

He offered it to her. “Put hair on your chest.”

“Did you really just say that?”

“What?”

Trisha looked at her chest and back to her brother, who shrugged and tried to hand it to her again.

“I think I’d throw up,” she said.

He shrugged again. “Best beer on the planet.”

“No.”

Weevil took a big swallow and wiped his mouth with the back of his giant, hairy arm.

“Good to see you, sis.”

“I can’t say the same.”

“Oh come on. Tell me you weren’t sick of being that stupid retard.”

Trisha prickled. “Don’t say that.”

“Okay. Halfwit. Better?”

Last year, before Georgie ran away, Trisha had loved this kind of banter. They could go at it for hours, making circular little arguments back and forth at each other, changing a word here and there to give different contexts to what the other had said.

Knowing what Georgie had become, it grated at her. She’d had enough.

“What are you doing here, Georgie?”

“Weevil.”

“No,” she said. “You’re not.”

“But I am. I run this part of the city. I got three guys within earshot’ll say I’m the boss. Thirty more just a couple steps down the chain. I got policemen in my pocket. Hell, you saw the vision. You know exactly who I am.”

“If you’re Weevil, then my brother is dead.”

He snorted and tried to stroke the side of her face. She pulled away.

“I am Weevil and your brother,” he said. “That’s the difference between you and me, sis. You’re still figuring out who you’re meant to be. Me, I found it. Weevil is exactly who I’m supposed to be.”

“I don’t think the real Weevil feels that way.”

“Don’t you get acting all high-and-mighty on me, sis. I saw your life at the same time you saw mine. Geez, all that time stuck in the body of Fat Reggie … How’d you do it? We’re the lucky ones, sis. We’re not trapped by our genetics. We just have to find who we’re meant to be and we can be it. I mean, look at you. Detective Palmer? Niiiice choice. How’d ya think she’d feel knowing—”

A touch of pure evil entered Weevil’s eyes.

“What?” asked Trisha.

“Nothing,” he said, but he turned to his desk and, after picking up his phone, he dialed a few numbers and he whispered a few words Trisha couldn’t quite make out.

When he put down the phone Weevil changed the subject entirely. “How’s dad? What’s he calling himself these days, anyway?”

The question caught Trisha unexpectedly. She’d become Fat Reggie shortly before her father made the transition to that last phase of their lives together. She struggled with the fractured memories left over from Reggie and finally came up with the title on the sheet her father had written up for that shift: I am Reggie’s Father.

Oh.

The tears started welling up in her eyes all over again. He’d sacrificed his entire identity after Georgie had left—given up everything—so that he could be her father. Nothing more.

But that title suddenly meant everything to her. She wanted nothing more in that moment than to leave Weevil to whatever he had planned and go back home. To hold her daddy just one more time and tell him that she loved him.

Trisha realized that Weevil was watching her, and she snuffed away her runny nose and wiped the tears out of her eyes.

“I thought so,” he said. “Now, sister dear. I have a plan. And you’re going to help me. Because if you don’t, I will see to it that our father suffers. Greatly.”

Trisha nodded and sniffed. “What do you need me to do?”

Weevil smiled. “It starts with the murder and replacement of Detective Janet Palmer.”

Trisha jumped out of the chair and dove at her brother. Her fingernails dug at his face leaving long claw marks from his eyes down into the scruff of his beard. She kicked. She fought.

She lost the fight.

Weevil pinned her to the ground, hands held behind her back. His knee planted itself into her kidney and he pushed down with all his weight until she screamed for mercy.

It took two thugs to help Weevil keep her under control. As they bound her hands and feet Weevil pressed his hand against the scratch she’d left on his face. He winced and pulled his hand back, staring at the lines of blood that ran down his fingers and across his palm.

As the thugs carried Trisha from the room, she heard Weevil yell after her. “Just for that, Ms. Palmer. Just for that I’m bringing him here. You’ll watch me break him. One bone at a time. I’ll cut off an inch of his flesh every time you blink and I don’t give you permission first. You hear me? You think on that, Ms. Palmer. You think on that.”

Trisha’s body bounced as the thugs carried her farther back into the depths of Weevil’s Club. In the occasional overhead light she searched the faces of the two thugs.

One of them she recognized but, from her current perspective, being carried upside down between the two of them, she couldn’t quite place. Only once they dumped her and she got a chance to orient herself did she recognize him—or, rather, the part of her that had been Reggie recognized him: Uniform Musclehead. Officer Burke.

Weevil gave strict instructions that Trisha was to be searched thoroughly before they locked her in that empty back room. “Leave nothing she can write with,” he said.

And Burke knew how to be very thorough. By the time he was done Trisha had been completely violated.

At last they dumped her, bound and gagged, on a cold cement floor in an empty storage room. She heard the door close and lock behind her.

And she wept.

Everything she thought went into forming the perfect character for Detective Palmer—the fierce determination, the perfectionism, everything—cried out at Trisha demanding to know where she had gone wrong. If all these things were supposed to make her good at being a policewoman, how did she get here where everything was broken?

And, adding insult to injury, if she was such a tough woman, why had she been crying so friggin’ much? Her eyes stung. Her throat felt tight and tired. Her nose ran.

She grew angry at herself—at what she had become and what she had allowed to happen and, above all, at her tears, and she set herself a goal. One thing to focus her fierce determination on.

Escape.

She found that her hand could almost slip through the cords they’d tied her wrists with. Only the thumb kept her hands bound.

If only she could write herself a smaller hand.

But there was nothing to write on. Her fingernails couldn’t even scratch at the cement.

And if she pulled any harder she was likely to—

Break.

Her.

Thumb.

She could. She could break her thumb. If she pulled hard enough … It would hurt in ways she couldn’t possibly imagine, but her fierce determination kicked in and she knew it was possible.

She closed her eyes. She arched her back. She bit into the cotton of her gag as hard as she could.

She puuulllllllllleeed.

Crack!

The pain smothered her. Her vision blurred and filled with white snow. She gasped and fought for each breath.

But her hand—

—came free!

When she looked at her hand the pain returned, fresh and new. The thumb dangled limply below an open wound, through which a shard of bone jutted. Blood ran down the front of her hand, pooling on the cement.

She closed her eyes and took several deep breaths.

The past several hours had convinced Trisha of one thing: She was not the person who could stop her brother. She was soft. Stopping her brother required someone cold.

No. Trisha Palmer was not that person.

But she could become that person.

She dipped her finger in her own warm blood, then, rubbing her finger across the coarse surface of the cement floor, she began to write.

The city is a cold place. Look in the eyes of the people, you’ll see it for yourself.

When the days get long and temperatures go up, tempers go up, too. There ain’t no howdy-doo to your neighbor. No, you’d sooner beat him over the head than have to listen to another note of what he calls music.

Arguments spring up over the littlest details. Need to borrow a cup of sugar? What? You blew it all on weed and now you can’t afford to make little Timmy cookies?

Serves you right.

Go away.

And that’s just the regular folks.

Try walking into a place like King Street on a hot summer night when “sweltering” doesn’t even begin to cover the way the neighborhood feels. See what you get then.

But there’s always some busybody, thinks it’s okay to be a good neighbor. Thinks it’s good to do the right thing.

If they’re not careful, they’ll end up in a world of hurt.

People like that need somebody wise to the ways of the city. Somebody who can smell the trouble they’re about to step in before it messes up their nice new shoes.

You got troubles? Who doesn’t. But if you ask nice, maybe you can find somebody willing to help a fella out.

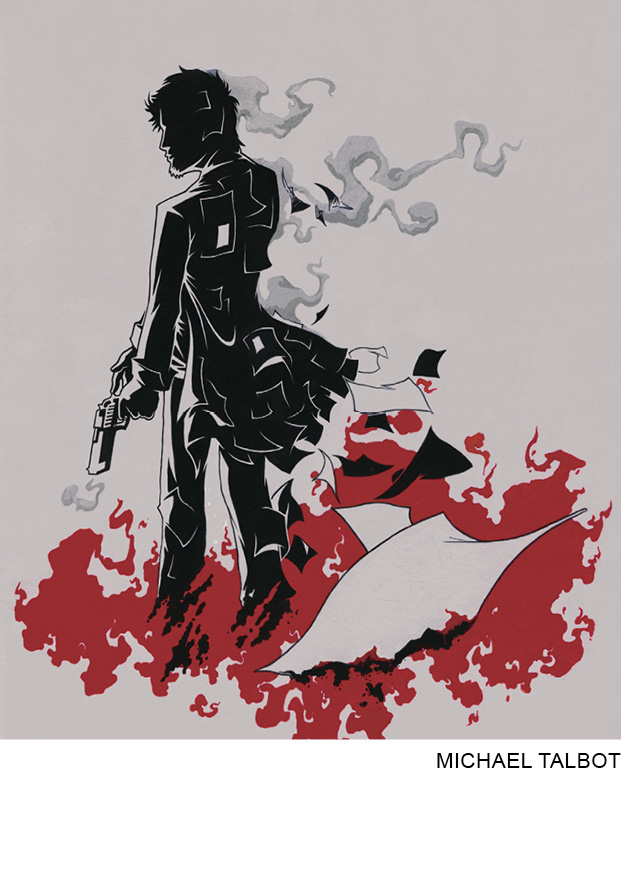

Trevor Nichols didn’t hesitate when the goons opened the door of the cellar he’d been stashed in. He jumped and he jumped hard. Drove the leftover piece of Trisha’s thumb-bone into the throat of the big muscleheaded turd who’d touched that poor woman where no man has a right to go without her permission. Drove his knee into the other goon’s stomach and twist-broke his neck while meathead gurgled out the last of his life on the floor.

Just another day at the office.

He borrowed the clothes from the second goon—less blood; besides he don’t need them no more—and swapped them for the ladies’ clothes he’d been wearing. Just a good thing nobody saw him dressed like that. One thing Trevor had never been able to stomach was embarrassment.

Meathead had a pea-shooter tucked away in the back of his waistband. A Smithfield Armory nine mil. Very nice. Trevor checked the magazine—full—and pulled back on the slide, chambering a round.

He worked his way back through the hallways behind Weevil’s Club, listening to the music pounding away. People who listen to that need to get their ears cleaned. Hell, people at a place like Weevil’s on a Friday night need to get a life. Get out of the city. Breathe some fresh air once in a while. It does wonders.

He just hoped the music was loud enough to cover the racket he was about to make.

At the back door to Weevil’s office he paused, gun held at the ready. He opened the door just a crack and peeked inside.

Janet Palmer crouched uncomfortably in the oversized leather chair in front of Weevil’s desk. Why uncomfortably? It’s a little hard to relax when a man the size of Weevil’s holding a gun on you.

“Honestly,” he was saying, “you should be dead already. But I had to see your face when you meet my sister.”

Janet didn’t shrink at all in the face of Weevil’s threats. Oh, she was nervous—who wouldn’t be? But she wasn’t backing down. Trevor admired that in a woman.

“This shouldn’t be taking so long,” Weevil said, glancing toward the door. Trevor ducked out of sight, but it was too late.

“Is that you, sister dear? Come out, come out, wherever you are.”

Trevor steeled himself, taking a deep breath. No sign of his old man. Trevor sincerely hoped they hadn’t got to his father already.

“Let me put it this way,” Weevil said. “Come out right now, or I kill her right now.”

Trevor pushed the door open and strolled in as if he owned the joint. He nodded to acknowledge Detective Palmer, but kept his pea-shooter trained on Weevil.

“Your sister?” said Janet.

“She has been a naughty girl,” said Weevil, keeping his gun on Janet. “We’re going to have a nice long visit after this—just you, me … and our dear dad.” The look on Weevil’s face could kill puppies.

“You found him already?” said Trevor.

“Not yet. But we will. So nice to have someone you care about, unlike Miss Palmer here. She’s all alone. No one to miss her when she’s gone.”

Trevor took a step forward; his finger tightened on the trigger.

“You won’t do it,” said Weevil. “I saw your life just like you saw mine. Leaving dad all alone to come find me. Tsk-tsk, Trisha.”

“Trevor.”

“Whatever—the point is, we’re supposed to do this together.”

Memories. Jumped out of nowhere. Trevor’s mind filled with memories.

A cheerleader and her brother, celebrating a state championship after the big game.

Two old wizened cab drivers playing checkers in the station after a shift.

Two hungry Cambodian boys, trading each other food in the line at the shelter.

Sisters giggling at the naughty gag gifts at a friend’s bachelorette party.

Trevor lowered the gun, just a fraction of an inch.

Weevil pulled the trigger. Red mist exploded from Janet’s chest.

Trevor drilled him. Two to the chest. One to the head. Right between the eyes.

It was over.

But for the first time, he’d hesitated. He’d been too slow.

And Trevor was left facing the one emotion he dealt with worse than embarrassment.

Guilt.

Trevor leaned against Weevil’s desk, watching the lifeblood trickle from the two dead bodies.

He did not know what to do.

There was maybe only one person who would.

He picked up the phone on Weevil’s desk, fumbling with the buttons until he found one that gave him a dial tone, and he called old Ms. Baxter. His father didn’t have a phone. Ms. Baxter would have to do.

She answered on the third ring.

“Hello? Ms. Baxter? I’m sorry to bother you, ma’am, but I’m—” How could he explain it? He couldn’t. All he could do was ask for his father—by the name his father had chosen for himself. “I’m trying to find Reggie’s dad.”

There was a long pause and Ms. Baxter said, “I’m sorry. Them Williams boys done moved out. They gone, both of them, as of a couple weeks ago.”

The news shook Trevor deeper than he thought possible. His breath caught and he swallowed to keep his emotions in check. “He moved out, did he? Well good for him. Best of luck to them both.”

Trevor hunted the back rooms of Weevil’s Club until he discovered a janitorial closet. There, among the foul smelling chemicals, he found a bucket, some bleach, and some mops and brushes.

With these in tow, he returned to the cellar where Trisha had become Trevor.

He read the words he’d written.

This was not who he wanted to be. But who was he? Weevil had been right about one thing—they weren’t bound by genetics. They really could become anyone they wanted to.

The only thing Trevor knew for sure was that he did not want to be Trevor Nichols.

Trevor Nichols had a part to play, but his part was over.

Trevor took the bleach and the brushes and, for the first time in his life, erased the words that had created him.

Weevil’s office stank like the sewers of hell when Trevor finally returned. His fingers stung from the bleach. His eyes burned from the fumes. But the smell of smoke and gunpowder and death overpowered everything.

Trevor pitied that little pine-scented candle. It was doing the best it could against hopeless odds.

But Trevor felt he owed a moment of respect to Janet Palmer. She had put him on this road, and he had to believe that some good had come of it.

And if Weevil was telling the truth, Janet didn’t have anyone else who would mourn her loss. That didn’t seem right.

The more Trevor thought about it, the more he thought this steel-willed woman deserved more than that. Someone needed to know who she was. Someone needed to tell her story to the world.

He fished through her pockets until he found her wallet and badge.

Forty-seventh Precinct. No wonder Trisha hadn’t been able to find her.

And there, on her driver’s license, was her address.

Impulsively, Trevor leaned her body forward and checked the back of the chair. The bullet had gone completely through Janet’s body, but not through the chair itself.

With a knife from Weevil’s desk Trevor cut through the leather and padding until he found the wooden frame.

There it was. The bullet that killed Janet Palmer.

He cut it out of the frame and put it in his pocket. One last memorial to take with him.

As he opened the door to the main part of the Club, Trevor saw the lowlife scum who populated the booths and tables, who played pool with stolen money. He saw dealers selling hash and weed to the poor idiots who didn’t know to do any better with their lives.

The utter hopelessness Weevil’s inspired in him drove Trevor to make one final decision. He took some of the papers from Weevil’s desk and held them in the flickering flame of the pine-scented candle.

Once they were going, he dropped some in the paper-filled trash can, put others in the filing cabinet. He spread the flames to everything that could catch fire until his lungs burned from the smoke and he could barely see to make it to the entrance.

When the fire alarm went off, Trevor escaped into the street with the rest of the crowd.

Janet Palmer lived in a quaint little red-brick home in the suburbs just east of the city. It wasn’t a rich neighborhood, but it was a long way from the atmosphere of the city.

It was dark. And quiet always came with darkness to a place like this. Still, Trevor doubted it got much louder during the day.

Trevor smelled the air. He could live in a place like this.

The third key on her key chain opened the front door. The little entryway smelled of potpourri. His steps echoed off the slate gray linoleum. “Hello? Anyone here?”

No answer.

Pictures on the walls showed Janet at different stages of her life. Pigtails. Braces. Proms and graduations.

In each photo Janet was surrounded by a different family.

Foster care.

Trevor’s impression of Janet grew by leaps and bounds—she’d been able to come out of the system and end up a decent person, trying to make the world a better place.

The closets in her room, filled with suitable and attractive clothing. Her bed, neat and tidy. Covered with pillows and a few stuffed animals. Her drawers held sports gear and workout clothing.

Trevor wondered what it would feel like to actually work for a body instead of simply writing one into existence.

Janet had turned her guest bedroom into a library. She read mysteries.

Appropriate.

But the real treasure was Janet’s journals. Two shelves full, volume after volume. Janet kept a detailed record of every event in her life.

Trevor sat down, cross-legged on the floor, and began to read.

September 28, 1992

Mom is helping me write this. Today was my first day of third grade. Mom says I should write where I’ve been and to write my dreams.

Trevor kept reading. He read of her parents’ death in an automobile accident. He read of her abuse within the foster system. The policeman who had helped her and who had arrested the foster father who’d perpetrated the abuse.

He read of her hopes for adoption being dashed over and over again. He read of the joy she felt when she stood up to the class bully in eighth grade. Of her first crush. Of her heartbreak when her fiancé died during military training exercises. He read of friends made and friends lost. Of triumph and success in the face of crushing defeat.

When he finished, he knew.

His whole life—excepting maybe these past few weeks—it amounted to nothing. A figure, hiding in the shadows, afraid to live for fear of being discovered as the unique creature that he was.

Janet Palmer—she’d lived.

And Trevor was extremely jealous.

He wanted that. He wanted to come home, the way Janet did at the end of every day, knowing he was working to make a difference. To bring order to the face of the chaos in the world around him.

And it was completely unfair of the world to leave a wretched creature like him alive and remove the Janet Palmers of the world from their rightful place.

Well, that was something Trevor could do something about.

He found a pencil in one of Janet’s desk drawers.

At the beginning of the first volume, at the top of the page, in big bold letters Trevor wrote: This is my history.

And, writing lightly so as not to smudge a single letter of her hand-written journals, he began to trace every word.

The sun rose and set. The phone rang and went unanswered.

Trevor continued to trace.

Every.

Word.

The last entry was dated July twenty-seventh. Three days ago.

And when, at last

I finished writing, I looked at myself in the mirror. My blonde hair popped out at odd angles from the sides of my head, a mess of snarls. My eyes, bloodshot and tired.

But I recognized my reflection. And I liked who I’d become.

Only one thing was left to do.

I removed the bullet from Trevor’s pocket and, lying on my back, I placed the bullet on my stomach. With the pencil I wrote an entry for today.

July 30, 2013

I don’t think it’s fatal, but I’ve been shot.

In a flash of pain the bullet disappeared into my stomach.

I awoke in the hospital. Tubes and wires sprouted from my stomach and arms. I heard the steady blip-blip-blip of the heart rate monitor.

Chief Leonart smiled at me from the corner of the room. I tried to answer him, but my throat felt as if I’d been eating sawdust and my nose felt as if it were under attack from the hospital disinfectants—they always remind me of the Nixons’ place back when they were my foster family.

A little nurse with red hair popped in and said, “Oh good, you’re awake!”

The chief gave me all kinds of crap about leaving Weevil’s after getting shot. I didn’t know what to tell him. My memory of the whole thing is still pretty shaky, to tell you the truth.

I just remember having this need to get home. To be somewhere I belonged.

One weird thing though.

After the chief and some of the guys from Vice had popped in and left, I was left alone with that little nurse.

She peered at me through some really thick glasses and did the strangest thing—

She held the sides of my face and put her forehead to mine.

I have no idea what that was about, but it creeped me out a little.

She apologized, but she had the saddest look on her face.

I haven’t seen her since.