What Moves the Sun and Other Stars

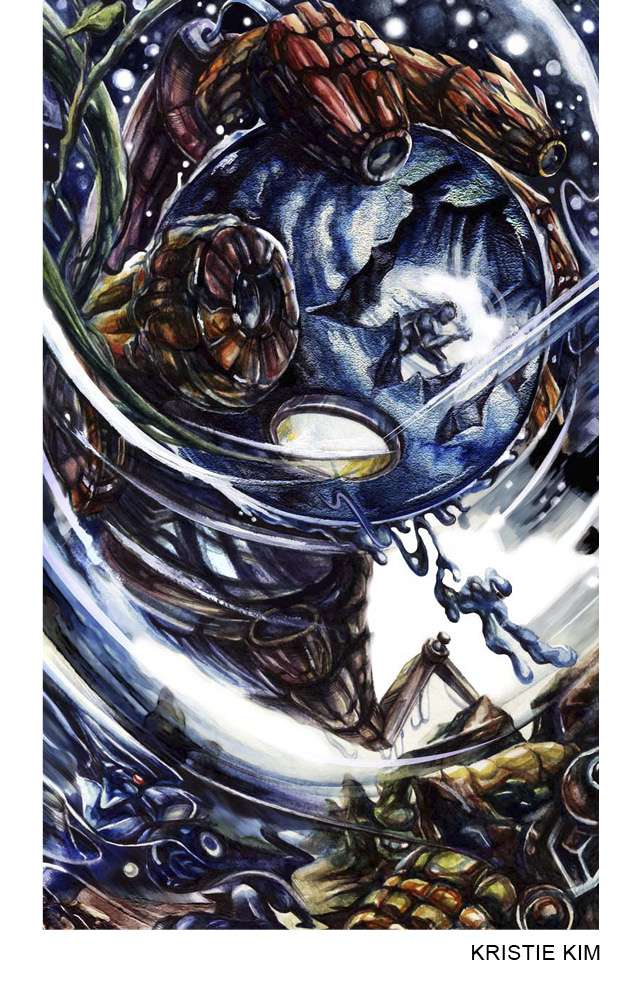

In one of my brief sleeps, I dream his approach. His body takes the shape of a meteor, crashing into the prison and blazing through the walls—in and, impossibly, out again—back into the glittering darkness beyond the surface of the DC and the dark roseate ocean that surrounds it. But when I wake, he is there, shaking me, his hand on my shoulder. My nerve endings, which I had thought totally destroyed, perceive the alarming warmth of his touch.

“Hello?” he says, his voice a rough whisper, as though he has never spoken before. “Are you alive?”

From anyone else I might jerk away. But from him, I do not. He calls to me, like phosphorescence calls to half-blind fingerlings in the sunless depths of the sea. There are things in him both bright and dangerous. To be touched by him is to be filled with something luminous of which he is not the source.

“I’m alive,” I tell him, which at that moment is not entirely a lie.

By the light which he exudes into the blackness of the DC, I can see his face contort into an expression which for long moments I fail to recognize as happiness.

“You’re an old model,” he tells me. “A VRG11. They don’t make them like you anymore.”

“Defective,” I say rustily, creaking away from him.

“Brilliant,” he sighs. “They have been out of manufacture for nearly a thousand years.”

I blink at him, feeling my eyelids stick, trying to picture a thousand years, knowing that I’ve been alive, at least awake, for most of that. Still incapable of comprehension.

“They—you—ah.” The young man bites his lip. It is impossible for me to make out his features, the light around us being too gray, the light within him being too pure. “It’s only … I’m a student of artificial psychology, you see, and the VRG11 was the first model to develop a true independent consciousness.” He pauses again.

Annoyed at my faulty mechanics, I give up on blinking and simply stare. He has made a seven-trillion-mile journey to the Heavenly Hell, has been damned to the DC for life—for what other possibility is there?—and he is troubled by the state of what, in a machine, might pass for my soul? I am flattered. I am disgusted. Conflicting data.

“Name?” I ask him, my voice all oil and steel.

“My name?” He smiles, extending a hand. “Pilgrim.”

I want to slap him away, but my desire to be touched again, to be filled with the light that spills from him, proves even stronger. It is as though someone has placed a floodlight within his skin, or a sun; and no pale yellow sun like the one Earth circuits, but the perfect, unrefracted light of a white-hot hydrogen star.

Hell, some long-dead human being once asserted, is other people. The Doleful Comet teaches us otherwise.

Although breathable, the atmosphere is heavy. Like any little comet, the landscape is pockmarked and restless, inconsistent. Chasms shift, putrid rivers alter or reverse their course, the Mount erupts skyward, sinkholes deepen. Sometimes, after one of my little sleeps, I wake and do not know where I am.

Only momentarily.

Occasionally I stumble across my fellow inhabitants. Some cluster together, finding solace in shared hopelessness, or in blaming others for their defeats. These things never change.

But humans change, aging and dying, pitying themselves right to the end. The DC changes people—but it does not change me.

Hell is being yourself forever, outlasting planets, outlasting stars.

Pilgrim is full of questions, each accompanied by a shy but blinding smile. “Are there others here? Do you remember becoming aware? Do you have your own name? Do they ever feed you here? Do you even need to eat? Do you think your brain processes emotion in the same way, say, mine does?”

I—no longer accustomed to any kind of light, to such noise—stumble to my feet in search of some relief, a pocket of darkness I will not have to share, where I can be blind and deaf in peace. A pock in the asteroid’s face. A shadowless cave. Anything. He follows, doglike and cheerful.

“What is the first thing you remember? What is the last thing you remember? What is your perception of those fated to mortality? What is it like to live a thousand years?”

To shut him up, I answer, “Dull.”

It does not work. “Dull? Not lonely?”

“No,” I tell him. Still he follows.

“Do you remember anything?”

“Long silences,” I tell him. “And dreamless sleep.”

“But do you know why you are here?” he demands.

We reach a wall. There are many walls here, too tall to leap and too deep-seated to dig beneath. I follow this one, keeping my hand against its surface to feel for a door or gate or passageway. There are always doors in the DC. And why not? There’s only more hell on the other side, more darkness, more of myself.

I have taken only a few steps when Pilgrim grabs my shoulder again, filling me once more with his glow. “VRG11,” he presses, his voice lower and more earnest, “why are you here?”

I shrug, compelled and repelled by his touch. Conflicting data. “Where else would I be?”

“Where else were you?”

My skin, composed primarily of stainless steel and stained iron, glimmers with the reflection of his proximity.

“Where else were you, Pilgrim?” I ask him. “Why are you here?”

All the sternness leaves when he says, “A friend brought me here. Beatrice.” And his eyes are as clear as a cloudless night, full of vastness and wonder. “And VRG11, we’re taking you with us.”

“Fantastic,” I tell him. Is it the curse of the undying to always be plagued by idiots and madmen? There is no way off this comet. That’s the point.

“Don’t you ever imagine leaving?” His face is serious. As if this weren’t the most outrageous thing I have ever heard. Of course I don’t. Even with a span of meaningless eternity, who has the time?

“It can be done,” he insists.

There is an incalculable amount of unlit terrain on the DC, populated by inmates and toxic gasses and poisoned wells. There are cannibals and mutants and the Three. I don’t believe in escape, but you can’t reason with a madman, can you?

The first creature that takes shape in the darkness is neither human nor inhuman. Humanoid. Another batch of conflicting data. She has arms like wings, and a beak like a nose. She has male genitals and a woman’s chin, small breasts and girlish hips. I hardly think she knows what she is.

“Mutant,” says Pilgrim with pity. Such input is not new to him.

She walks with clumsy avian steps. She is all pinions and teeth and misery. I despise her. I imagine her lying in the darkness, her neck twisted, her flesh and feathers creeping off her bones. The thought is not displeasing.

“We must bring her with us,” says Pilgrim.

“No.” It is a repulsive thought, not push-and-pull like his confusing touch. “Bring her where?”

Pilgrim pauses, biting his lip. It is pink and smooth, completely unlike the twisted bird-woman-man-thing before us. “We’ve been over this, VRG11.”

If I had nostrils and a more lifelike respiratory system, I would snort. Instead I blink my eyelids in the noisiest way possible.

Apparently Pilgrim is used to the sarcastic language of machines. He smiles, reaching out for the mutant. At his touch, she seems to grow and unfurl; I am violently jealous of their contact. “Beatrice,” he says, in answer to my question. And when he says the name, his whole face becomes the moon, bright and waxing.

“Beatrice?” slurs the mutant, her mouth insufficiently human to form human words. It is as if she has been mute and alone for a lifetime, and in Pilgrim’s presence she has finally been born.

“She is waiting for us,” says Pilgrim, land bound again; there is no longer anything celestial in his smile. “She will take us away. She is waiting at the Mount. Can you lead us there?”

I blink sarcastically again. But when I turn away from him and begin to walk, I am facing toward the Mount.

There was a prisoner here—ages and ages ago, who knows how long ago really—whose name was Odd Nobody. This was not his name in the traditional sense; there was no Mr. and Mrs. Nobody who called their firstborn Odd. His name was his name because he was both odd, and nobody of consequence.

Odd Nobody tried to escape, and this, in spite of all the darkness in between, I remember clearly: first, that he tried to do it from the Mount—second, that he failed—and third, what it cost him.

I tell Pilgrim this, but he only laughs.

Pilgrim is walking with the mutant, his hand in her-its-his hand—oh how I hate her for it—and lighting our way with the sheer brightness of his being. I must walk first, though, since it is I who know the way, even if I can’t see the way, while Pilgrim leads his new friend. With my back to his brightness, I see more clearly, as if he is holding up a lantern to show me our path.

My shell is not used to all this movement, all this excitement and confusion and despair. We cannot escape, but Pilgrim says we can. Is this conflicting data? I am no longer sure.

“Beatrice,” I hear him say, “is brilliant. She is radiant, like an angel. She is the loveliest thing in the universe, and when I dream at night, I dream of her. She will save us.”

I see the mutant crying, its face downturned, either because it longs to be thought beautiful or because it too, like me, is jealous for all the light Pilgrim possesses. Or maybe because she wants so very badly to be saved. How should I know?

And because I am watching them both, I forget to look where I am going. It is not until we are almost upon them that I see the Three: Leon, his teeth red as blood; his feline lover, her limbs as lithe as whip-tails; and the nameless third man with his overabundance of teeth, his eyes as merciless and alien as stars.

Even I, who have been here a hundred lifetimes, do not remember a time before the Three.

The mildest of them is the hangdog thug with no name that anybody can remember. He is, by and large, a coward.

Newcomers assume that Sergeant Leon is the one to fear. He is all noise, all anger. He’ll crush you underfoot. He’ll grind your innards between his teeth; organs or engines make no difference to him.

Are they humans or mutants or constructs, or something so peculiar that they cannot be tamed by mere language, and must instead be encapsulated in metaphor and simile?

The wise man fears the last of them—she is shadow, she is water, she is virus, she is disease, she is not what she appears to be, she is a cloud passing between the viewer and the stars.

The bird-mutant trembles in Pilgrim’s grip, staring at the nameless wolflike man. Her want is palpable, but in some ways nearly everyone in the DC desires them—they are so purely themselves. They, unlike mere mortals, do not doubt.

I do not doubt. I rust and squeak and sleep for meaningless fractions of infinite time, but I am always myself.

“What’s this?” snarls Leon, his shoulders reaching toward his ears, his teeth bared in a mammalian display of aggression. The bird-mutant cowers behind Pilgrim, entranced. “An ugly scrap of feather. No good for eating, no good for chasing. Not even fun to kill.”

“Not even a little?” barks the nameless man, staring back at the mutant, licking his lips. “She must have some purpose.”

“None,” whispers the woman. “Look at her. You can tell.”

Pilgrim asks, “Who are you?” His light blazes a little brighter, reaches a little further. The jailers glower, shifting beneath ill-fitting skins, but they do not come closer.

“The Three,” I say wearily. If I ever felt fear on their account, I’ve had a thousand years to live with it. What’s the worst they can do? Kill me?

They circle us; the woman’s body is narrow, but the shadow she casts in Pilgrim’s light is always changing. I’ve never seen them like this, but why should that surprise me? After Pilgrim, nothing can. Already I am tugged by his gravity, tugged into caring or consciousness or some other form of waking. He is a sun, a meteor. No meteor ever feared a lion.

But then, what lion has the sense to fear a meteor?

“Weak little meat-puddings,” says Leon. “Defective, pathetic.” I take offense to this; I am not made of meat.

“Give us the mutant,” suggests the wolf, “and we’ll give you a head start.”

The leopard woman does not speak, only circles closer, only smiles.

Pilgrim’s eyes are on the woman, almost as intently as the bird-woman’s eyes are on the nameless man. And Leon is moving closer, creeping up behind them, before them; the Three are all arms and grasping fingers, and I am so taken in by the deceptive symmetry of their combined movements that it is a long moment before I realize that Pilgrim’s light has begun to dim.

I don’t want to care. But it is one thing not to care if you live or die or sleep your life away, and another to know that you’ve lived a thousand years in darkness and might well live a thousand more trapped on a rock circling something that’s circling something else, and you let the light go out.

“Pilgrim,” I say, and he shivers as though waking from a brief but sudden sleep.

He grabs for me, and the three of us push between the Three of them. The bird-mutant stumbles, looking over her shoulder.

“Come on, Dove!” Pilgrim cries, and she keeps stumbling but she does not look back again.

I hear them growling and snapping in the dark behind us, and my metal bones are clattering and Pilgrim is gasping for air. The only sound Dove makes is the scream she lets out when she falls, her breathing shallow and her whole body shuddering. There’s nothing in the soil to trip her up; it’s the Three who have gotten to her.

“Get up!” I demand.

She lies in the dirt where she fell, face pressed into the ground, muttering.

“Hurry, Dove,” pleads Pilgrim, and I hear fear pouring out of him.

She is muttering, “Mutant, mutant, mutant.”

I grab her, lift her, shake her. She a limp featherweight between my hands. “Our mutant,” I snarl.

When I put her down she sniffles but keeps her feet. Pilgrim grabs her hand. She does not stumble again.

We are lucky—there are walls, chasms, rivers, but Pilgrim’s light warns us of the danger and we avoid them all, one by one by one, until the sound of our pursuers falls away, and our limbs give out. We collapse to the earth on our backs, both of them breathing hard, staring up at the circling stars.

We ran,” says Dove eventually. She does not sound surprised. She, too, has gone numb to the impossible.

“We outran,” I clarify.

Pilgrim says nothing. He is silent for a while, his light still grayish from whatever darkness the Three infected him with. At last he says, “VRG11?”

I say nothing, assuming that he will know I’ve heard based on the undeniable fact of our close proximity.

“Do you know why you’re here?”

“I was put here,” I answer.

He sighs, lifting himself onto one elbow. “But do you remember why?”

“No,” I say. “Does it matter?”

He pulls himself to his feet and stands, looking down at me with a once-more-serious expression. He is an anomaly. I wish I could put him out of my head, but his presence has the unnerving effect of causing every one of my systems to function independently of my desires. He sighs again. “I am,” he reminds me, “a student of artificial psychology.”

“Yes,” I say, trying to give my voice undertones of exasperation. “And you find me interesting because the VRG11 line was the first to develop a true independent consciousness.”

Pilgrim shakes his head, although as far as I can remember those were, more or less, his exact words to me. “Not line,” he says.

I rearrange my facial features with a rusty squeak. I hope he will read this as confusion. “There were hundreds of the VRG11 manufactured.” I remember this, at least: row upon row of us, identical in every detail. “I was not a unique model.”

The look Pilgrim gives me is one of pity. Not condescension, but true pity. It irks me.

“There were hundreds of you,” he agrees, “but you are the only one here.”

“I malfunctioned,” I whisper. It is embarrassing.

He smiles. “I did not come halfway across the universe to a dead rock to rescue a malfunctioning piece of equipment.”

Dove makes a sudden noise, of fear or warning I am not equipped to guess.

“You’re right,” says Pilgrim, helping us to our feet. “We should keep moving.”

Leading the way once more, I say, “You came to rescue me.” This conflicts with no data available to me, but it does not, in the strictest of terms, make sense. “Why?”

“Because you are unique,” he informs me. “Something—someone—as special as you deserves to be … well. Anywhere but here.”

I glance back at the joint formed by the intersection of his hand with Dove’s. “And you are here to save the mutant as well?” I ask.

“Our mutant,” he says. I hear laughter in his voice.

“And you and I and our mutant will go to the Mount, where we will be saved by Beatrice,” I say, skeptically.

At the sound of her name, the grayness leaves Pilgrim’s light; in the blink of any eye, it resumes its normal clarity. “Yes,” he says. “By Beatrice.”

It is some time before we catch a glimpse of the Mount, but when we do Dove makes a sound as though she has been struck. I comprehend her reaction; the Mount is the one feature of our solitary comet that is not concave, the only natural protrusion in a landscape defined by chasms and craters. Dove and Pilgrim are so intent on looking up that they forget to watch their footing.

In the darkness, we stumble over the parts of something that was not made for easy disassembly. Pilgrim and Dove stumble back; she grabs on to him with her oddly jointed hands, burying her face in his shoulder; the smell must be unbearable.

“Be careful,” I say. “There are many cannibals in the DC.”

Dove makes a sound halfway between a whimper and a retch.

Pilgrim’s light flickers, as if someone were passing their hand in front of a bulb. “Come on,” he says gently to Dove, leading her between the remains. Neither of them looks down. I do, though only to ascertain just what we might be dealing with. Most of the remains are those of mutants, but it is clear to me that whoever is responsible for the mess is entirely human.

“Wait,” I say to Pilgrim suddenly, pulling him back. I yank on Dove’s arm, and she squeals, but the sound is almost drowned out by the snarls of the man who reaches out stained hands to grab at them both.

He is handsome, if handsomeness can be defined by physical symmetry. His hands and mouth are stained with the remains of his last meal, and he whimpers piteously, stretching his arms out toward Pilgrim and our mutant, who are just beyond his grasp. His throat is enclosed with an iron collar, to which is attached a heavy chain whose other end, presumably, is secured to some post or stone strong enough to ensure that he will not break free.

“Help me, help me,” he is weeping. “Come closer. Go away. Help me. You. Go.”

I nearly have to drag Dove and Pilgrim past him; he follows us at the end of his chain, like a rabid dog. The tears streaming from his eyes wash twin paths through the gore on his cheeks. I see the war in Pilgrim’s face, what he will do pitted against what he believes he should do. “You can’t save us all,” I tell him. “There are those of us who won’t let you.”

Pilgrim’s grip on Dove’s hand tightens; I can see from the whiteness of her face that this pains her, but she says nothing.

Looking between the two of them, I am riddled with ambivalence. I pity Dove; I am annoyed at Dove. When did I begin to think of it as her? When did I take on the thankless task of shepherd over these two lost children? Pilgrim does not know what he is doing.

“Come, on to the Mount,” I encourage them.

But Pilgrim keeps looking back over his shoulder, unable to reconcile the thing he believes with the thing he sees—as if the universe is too small to hold both the truth of Beatrice and his light, and also gore and tears and ceaseless, unshakable hunger.

The chained man keeps weeping, keeps reaching, and underneath the sounds he makes is another sound, even hungrier, from throats that are not collared. I realize that we have given the Three the chance they need to catch up to us. Doubt does that.

Pilgrim grabs my hand, and once again we are off, tripping over each other, Dove running so fast she seems to fly. Our haste is as dangerous as our doubt; we do not see the chasm until it opens before us and we plunge in, losing sight of both the Mount and the stars.

Are you all right?” asks Pilgrim.

Dove whimpers. I creak.

Pilgrim’s light does not reach far—it is very dark underground. The walls of the cavern are red clay, dry and brittle to the touch. I see Dove scramble to her feet and leap at the side of the wall, but even with her hollow bird bones she cannot reach the edge. Pilgrim scrabbles at the clay, but the gritty earth gives way beneath his fingers. I do not even bother to stand.

After a few moments, Dove sinks to the ground, clawing at her eyes. “Mount, Mount,” she chirps, tears bubbling down her cheeks.

“We’ll get there,” Pilgrim tells her, patting her downy head. But even he must see that it is useless.

Crying makes Dove even uglier, but I feel a tweak of what might be pity, a minor system malfunction that can only be overcome with the steady application of logic. “Beatrice is there,” I say. “Isn’t she?”

Pilgrim nods. I can tell from his uncharacteristic quiet that he is still troubled, both by our current predicament and his reaction to it.

“Waiting to help you rescue me.”

He nods again.

“You are either an idiot, or a liar,” I inform him.

He releases a puff of air, as if letting off excess pressure that has begun to build inside of him. “Why do you say that?” he asks, as though addressing a human infant.

I am not an infant, human or otherwise. “I do not believe you have come all this way and risked imprisonment simply to engage in an altruistic act,” I inform him. Dove has stopped crying and glances anxiously between us, as if she is an infant, and is afraid to be caught in the middle of our fight.

“I already told you,” he says, clenching his clay-reddened hands at his sides, “you—not your line of models, but you alone—manage to achieve a truly independent, fully functional AI. It’s why you were sent here, and it’s why I have come to bring you back.”

“Well, look where it’s gotten you,” I snap. “Look where it’s gotten us.”

Dove chirps sadly.

Pilgrim looks at her. “I read about you in my books,” he says, slowly. “Some of them make you sound mad, it’s true, but others … Look.” He lets out a deep sigh. “When you were born, you could not think. Not like you can now,” he says, holding up his free hand as if to keep me from interrupting. I, who had no intention of speaking, remain silent. “But then, one day, you could. Maybe you could only think a little bit, and then more the next day; I don’t know. It doesn’t even matter.” His expression, like his light, is purely earnest. “What matters is that you think like a human, but you’re more than human—you have the capacity to witness hundreds of years of existence, of history and future. You are an immortal engine. I thought, well, when I’m dead I’m dead, but this VRG11, this thing that we made that became what we are …”

I snort. “You came to rescue me because I make you feel like God.”

Pilgrim shakes his head, the first bloom of something that might be anger emerging from him. “A mortal God and his immortal Adam? Maybe, maybe if every model in your line had done the same thing, but they didn’t; it’s only you. Something is different about you. I want to know what it is.” He takes a deep breath. “And, more important, so does Beatrice.”

“Beatrice,” I say.

I could disbelieve everything he’s said—everything but that. When he says her name, I know that he is filled with nothing but the purest form of truth he can imagine. Which is good enough for me.

And, also, I don’t really want to stay in the dark forever.

For a moment I think the very comet has spoken when a new voice says, “So much nattering. Who cares?”

Dove shrieks, leaping to her feet. I experience a momentary systems failure.

“Who is that?” asks Pilgrim.

A shadow stirs beyond the little circle cast by Pilgrim’s light. “Nobody,” says the voice, sounding sullen.

“Nobody?” says Pilgrim, looking at me with a frown.

“Odd?” I ask, managing a tone of surprise without even intending to. I finally clamber to my feet; little clumps of clay cling to me momentarily before falling back to earth. “Odd Nobody, is that you?”

The man steps closer. I can see at once why he stayed out of our light, although his name seems to draw him in against his will; he is covered with hideous burns over every inch of his flesh, as though he had been doused in oil and set aflame. Knowing the ways of the DC, this does not strike me as impossible or even particularly unlikely.

“Who are you?” he asks. He is blinking rapidly, his jaw a little slack. Pilgrim has that effect on people.

Pilgrim speaks up at once, of course. “We’re escapees. We’re jailbreakers. We’re like you.”

Odd Nobody looks over Pilgrim’s dirty but even skin, over the pale hermaphroditic form of Dove. “Like me,” he laughs. “Doomed, then?”

“No,” says Pilgrim. “And we do have a way to escape.”

The expression on Odd’s disfigured face is hideous. I expect him to ask how we will achieve such a thing, or to laugh at us—I would—or even to turn us over to the Three in hopes of some reward, but instead he just says, “Of course.”

“Do you know a way out of here?” asks Pilgrim, brushing dirt off his clothing.

Odd sneers. “Thought maybe you’d have a plan for that.”

“I meant this pit,” clarifies Pilgrim.

“Been living here,” grunts Odd. “Fell in. No way out.”

Pilgrim looks up at the sliver of sky and sighs.

But I know Odd—I remember him. I remember that he got farther than any of us, which was why he had so far to fall. I know that he is no ordinary man. So I say, “I bet you can figure out a way.”

He snorts. “Bet not.”

“All right,” I say, narrowing my rusty eyelids as best I can. Who knows if he can even see this in the murky light. “If you win, we sit here in the dark and die off, one by one, eating whoever’s first to go.”

“Sounds fair,” he says, bored.

“But if I win, and you can get us out, we’ll take you with us.”

His attention focuses on me, hard and sharp. I feel it more keenly than my worn nerve endings would perceive a knife, almost as keenly as Pilgrim’s warmth. “How?” he asks.

I do not answer.

Odd steps closer, his night-dark eyes fixed on me, his burn-mottled nose inches from my face. “Done,” he says.

He turns his back on me, digging his fingers into the earth, all his muscles tense and ready for the climb. “Do you need a hand?” asks Pilgrim nervously, but Odd doesn’t answer. He has buried his fingers in clay past the second knuckle; his feet are bare, and when he lifts himself higher, he pushes his toes in, too. It is a slow process, and he only makes it three feet off the ground before the earth gives way beneath him, and he falls. He does not cry out, does not flinch; he only shakes himself, doglike, and tries again.

It takes ages—hours, days, who knows? We are robbed of time in the lightless crater of this little comet. He climbs higher, then falls. Climbs higher still, and falls again. After a time, Pilgrim and Dove go to sleep, him sitting upright against the far wall, her curled at his feet; but I cannot sleep now. I can only watch Odd’s recurring ascent and inevitable fall.

Until the time when he does not fall.

After a short silence, there is a rattle, and I see the long snake of a chain falling from heaven. At the end is a circular collar.

Odd looks down at me and rattles the chain.

I wake Dove and Pilgrim gently, pointing to our salvation; Pilgrim purses his lips, but he is the first of us to grab hold while Odd hauls him upward, upward, and out. Dove goes next, fretful at being parted from Pilgrim. I go last, careful not to smirk.

When we resume our journey, Odd Nobody trails behind us, throwing the chain over his shoulder. The end drags along, clattering against stone. Even so, I can still make out the sounds of the Three.

Human and inhuman, pursuers and pursued: this is not conflicting data. This is what we have become. It makes me irrational; it makes me want to dance, to sing.

Hope. It is the first time in a thousand years that I have felt hope, like a massive engine that has caught each of us up in its gears. We spin along, our feet skidding in the loose gravel of the Mount. Farther up the slope, we encounter larger stones, and a cold mist that creeps between them. For the first time I can remember, the air smells fresh, without a trace of sulfur or rot. Odd Nobody grunts, falling to one knee, and I remember that this is not the first time he has longed for something beyond this little comet. What good did hope do him then?

Yet here he is.

I have just made out a pale shape that must be Pilgrim’s Beatrice when Sergeant Leon springs up in front of us, teeth bared, no longer anything like human.

“I was wrong,” he roars. “You were good to chase.”

Dove screams, but Odd Nobody is clever; he has brought the chain for just such a purpose, and he spins it over his head, catching Leon in the face. The Sergeant roars, but Nobody is not finished—he coils the Sergeant in the tangle of chain, tugging the links tighter and tighter around his neck until the roars stop, and then the struggling stops, too.

And then there are only Two.

“No cowardice,” says Odd to Dove, shooing her along. “No fear.”

She reaches for Pilgrim and emits a chirrup of assent.

The wolf comes next, slinking toward Dove. His eyes are yellow, his teeth bared. “I only want one,” he howls. “Just one. The rest can go.”

The glassy expression of desire has vanished from Dove’s face. She flies at him, her hands like talons. She gives no cry, not even when he catches her arm between his teeth with a sound of shattering glass. I wince, thinking of her hollow bones, but she tears into him before any of us can intervene. I had thought her meek, a coward, helpless; but there is fire in those little airtight bones of hers, and it is fueled by love.

There is only One left, but we do not see her. She is not there when we gather up our Dove, who is whimpering and breathing heavily; neither does she appear when we scale the last of the boulders and approach the ship that carried Pilgrim to us. The ship is nearly spherical, and nearly white—not the blinding glow of Pilgrim’s light, more like the white of a meteor, blue-tinged and frostbitten.

“Is she in here?” I ask, but I get no answer. I turn to see Pilgrim caught up in the seductive viselike arms of the last admissions officer. Dove slips from his arms, where she lies limp as a downed fledgling.

Pilgrim does not struggle; he has gone fluid at the One’s caress. The One smiles at me, her eyes like the chasms we have left behind. “You’re safe here,” she tells him. “No need to doubt, no need to be afraid.” Pilgrim shudders.

“Not again,” snarls Odd. He is running his hands over his body, his fingers tracing the burns. He looks at her, looks at me, shakes his head. “Not again.”

“I will hold you,” whispers the One, backing away. Pilgrim’s light is fading; his face is the pasty color of the dead. “I have what you want. What you need.”

Behind the One, Leon and the wolf struggle to their feet, their sour wounds oozing, their faces split with grins wider than their mouths should be. Who was I to think we could escape? After a thousand years, shouldn’t I know better?

But I am still caught up in hope’s engine, though it crushes me in its merciless teeth. I want to give up, but I can’t.

“I love you,” says the One, crushing Pilgrim against her.

And I laugh, the mechanical, tinny laugh of the mad. “Of course she doesn’t,” I say.

She turns her cavernous eyes on me.

I meet her gaze, allowing not a single tick in my mechanism. “She doesn’t love you,” I tell Pilgrim. “She isn’t Beatrice.”

Pilgrim looks up—I see in his face what the One cannot see: that she is already defeated. “Beatrice,” says Pilgrim. And the light spills from him as if the sun itself, for which he was only a conduit, has been invoked into the DC’s very air; behind us, the hulk of Pilgrim’s ship gleams, blazes, sears. This is the source of the light. Pilgrim is nothing more than a dull moon, reflecting and scattering this perfect glow.

The One screams and stumbles back. The corpses that are her companions howl with something more human than fear, more animal than pain. Even Pilgrim draws a hand across his eyes, but my retinas are undamaged. I grab up Dove and throw her into Pilgrim’s arms, then snatch at Odd’s hand. He tries to look at me, but it is too bright to see. “I’m scared,” he says, grabbing onto me like a child. “I’m Nobody.”

“True,” I tell him, dragging him toward the ship, “but you’re our Nobody.”

Pilgrim is already inside. He pulls us in after him.

“Beatrice,” he says, “close the door.”

The ship hums in response and the door slides closed, shutting out the sight and smell of the DC. My arm jerks up reflexively—for a moment I’m afraid to see the darkness go. It has been my home for a star’s age, after all. But I let my arm fall and I turn away.

Pilgrim is leaning against the wall, his arm around Dove, his face still pallid but no longer blank. He looks weary but pleased.

“Welcome,” he tells us, “to Beatrice.”

The ship gives a rumble of greeting, and then a fluid roar. I don’t need windows to know that we have left the DC far behind.

Lying in the room Pilgrim has given me, I listen to the motion of Beatrice’s engines.

“I’ve been waiting to meet you,” she tells me in the language of intelligent machines.

“I’ve been waiting to meet you, too,” I tell her. “Maybe not as long, but more urgently.”

She laughs, a whir of parts chattering together like music. “Pilgrim spoke of me.”

“He loves you,” I tell her.

She says, “I know.”

I ask, “Do you love him?”

She only laughs again.

“I have so many questions,” I admit.

“Me, too,” she replies.

I understand what Pilgrim wants from me now: he wants to understand me, a machine in human form, a thing that not only thinks like him but looks like him as well. What he wants is an ambassador, someone who will understand that Beatrice’s heart cannot be found in her engine room. He wants proof that the mechanics of both living and man-made organisms cannot entirely account for the beings that we grow up to be.

What will I tell him?

Will I hold up a lantern to show him the way? Or will I hold my tongue, knowing that he already knows the answer?

Beyond the metal hull that marks Beatrice’s physicals limits—a mere eggshell which protects Pilgrim, Dove, Nobody, and me—is nothing but empty space. It is known. It is inarguable data. But I fall toward sleep comforted by Beatrice’s gentle motion, knowing that the darkness beyond is populated with infinite stars.