_fmt.jpeg)

South Beach, a small “pocket” beach between Long Beach and Florencia Bay.

2. Raincoast Riches

A FAVOURITE SPOT of mine is a pocket beach just around a rocky headland from Long Beach itself. Its pitch is steep, not shallow like the big beach, and it is filled with pebbles and cobbles, not sand. While Long Beach has calm days among the tempestuous ones, this beach never seems to rest. Each time the surf rushes back down to the sea, it sets the stones knocking and clattering against each other in manic chatter. Barely does the din subside before the next set of incoming waves prompts a new chorus.

On warm days, my daughters and I have lain on this beach, using fat sun-roasted stones for our version of a hot-stone massage (kelp facials optional). Rainy days here are the best ones for combing through the masses of sea-buffed pebbles to admire Nature’s exquisite handiwork and seemingly boundless creativity in dreaming up colour and pattern combinations.

When the tide and waves allow—for this can also be a dangerous beach if one doesn’t pay attention—I might climb one of the small columns of rock at the beach’s north end. From here, I can see over to another high promontory where friends of ours were married one stormy winter day, fittingly clad in wet-weather gear and custom-painted rubber boots. That day, wisps of golden sea foam churned up by the sea and caught in the wind swirled around the couple in place of confetti.

This is also a good place to view the open ocean. It’s not unusual to catch sight of grey whales on their yearly migration north from Baja California, Mexico, to the Arctic in the spring and then back south again in the fall.

Early native people living near here valued this site as well. This high point, with only one access, was a perfect lookout. It gave men a commanding view out to sea where they could watch not only for whales, an important food source for First Nations, but for canoes bearing neighbours, sometimes friend, sometimes foe.

The Coast’s Ancient Cultures

Native people have called the Long Beach area home for millennia. An archaeological excavation at Ts’ishaa on Benson Island in the Broken Group Islands (today about a forty-five-minute boat ride from Ucluelet) calculated human settlement there as early as five thousand years ago. It hardly seems necessary, though, to pinpoint the exact beginnings of aboriginal history on the island’s west coast. If human occupation was represented by a handful of beach pebbles, then the residency of non-native people would be but one or two of those small stones.

In a moist, humid climate like this, where wood was the primary building material, structures from the distant past do not survive as those of ancient civilizations in arid environments have. No pyramids here. Nonetheless, the history of Vancouver Island’s First Nations—here since “time immemorial”—is recorded in rock carvings (called petroglyphs), shell middens, stone fishtraps, and moss-covered house posts. It also survives in the stories and memories passed down through more than two hundred generations and in the language of place names.

Today, the native people of Long Beach and elsewhere along Vancouver Island’s west coast are collectively referred to as Nuu-chah-nulth, meaning people “all along the mountains and sea.” The name Nuu-chah-nulth was chosen in 1979 by fourteen of the First Nations living on Vancouver Island west of the mountain range that forms the ragged spine of the island. Formerly they were called the Nootka, a name incorrectly applied when Captain James Cook arrived in 1778 and which stuck for almost two centuries.

While the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations are connected through language, geography, and heredity, this collective name for all the residents of the west coast did not exist in the past. Instead, there were dozens of local groups made up of chiefs with territorial rights and privileges within specific areas. In the Long Beach area alone, at least six separate village sites existed between Cox and Wya Points. One was located at Green Point, the current site of the national park campground; another was at the south end of Wickaninnish Bay near the current site of the park’s interpretive centre; and a third was at Esowista, which remains a First Nations village today.

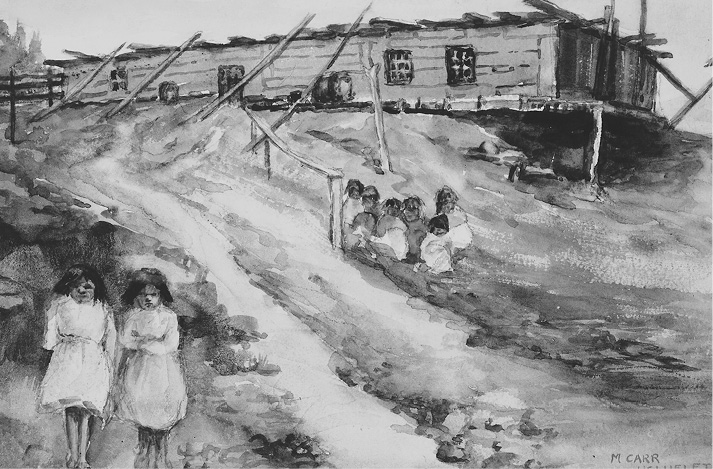

In the late 1890s, the British Columbia artist Emily Carr visited mission- ary friends at the First Nation village in Ucluelet Harbour. She sketched and painted the village’s buildings and some of its inhabitants during her visit and later wrote that it was there she was given the name Klee Wyck (Laughing One).

As occurs within all political states, boundaries merged and shifted over time. Their composition also evolved, often influenced by warfare or marriage. For instance, where the community of Esowista sits today was once a village of the Hisawistaht (Esowistaht), whose territory covered parts of Long Beach across to Grice Bay. Following four years of battles with the Tla-o-qui-aht (events collectively referred to as the Great War), all of the Hisawistaht are thought to have died, after which the land was claimed by the Tla-o-qui-aht. Today, Esowista is translated as “clubbed to death.”

Later, the effects of the Europeans’ arrival also drove amalgamation. In face of the extreme destabilization this contact wrought on the coast’s longstanding socio-political structures—made worse by plummeting population numbers resulting from previously unknown illnesses—many formerly independent groups banded together.

Today, there are two Nuu-chah-nulth nations whose traditional territories include lands in and around Long Beach. To the north are the Tla-o-qui-aht, whose name was anglicized to Clayoquot by early traders. Their territory encompasses much of the southern section of Clayoquot Sound, including the town site of Tofino, parts of Meares Island, the Kennedy Lake and Kennedy River areas, and part of Long Beach. Opitsat on Meares Island and Esowista at Long Beach are their primary villages today.

To the south, the Yuu-cluth-aht (Ucluelet) First Nation territory extends from Long Beach and around into Barkley Sound. The main village today is at Ittatsoo in Ucluelet Inlet.

A Life from Cedar and Sea

Come autumn, the paucity of deciduous trees on Vancouver Island makes the rainforest a little less colourful than other forests at comparable latitudes in Canada. Absent are the vibrant reds, yellows, and oranges of the eastern maples. Still, an October bike ride or walk along the Grice Bay Road reveals other forest treasures. The road here is lined with red alders whose leaves turn a mottled green and gold in the fall and look like ripple-cut potato chips. The upper branches arch overhead, giving the road a grande allée feel. Once the alders and salmonberry bushes drop their leaves, the forest behind them is exposed.

It was on one of my slower trips down the road that I first noticed a cedar tree with a four-metre- (thirteen-foot-) long strip of bark peeled away. The bottom of the strip scar was about a hand’s width across, and the whole section tapered upward to a point. Farther along the road, I spotted two more cedars marked this way and then others as I continued on. These were recent “culturally modified trees,” whose bark had been stripped by twenty-first-century Nuu-chah-nulth weavers carrying forward a traditional skill that has helped sustain First Nations culture on the west coast.

Along the trail to Halfmoon Bay is another, much older bark-stripped tree, a huge western redcedar. The scar is worn and greying now, but one spring, decades (or perhaps centuries) ago, a native woman approached this tree and addressed its spirit, thanking it for the valuable resource it was about to provide. She then used a knife of sharpened stone or shell to make a horizontal slice about a foot wide through the thick bark. Next, grasping the bark, she peeled the strip upward until it pulled away at the top. She folded the long strip in a bundle and strapped it on her back to carry home. There, she separated the soft inner bark from the rougher outer bark, ready to use in creating any one of dozens of items.

_fmt.jpeg)

Traditional skills and knowledge of the uses of redcedar are still passed on through generations of Nuu-chah-nulth people. Redcedar is harvested today near Long Beach by Nuu-chah-nulth weavers. Gisele Martin learned the art of cedar bark harvesting from her aunt, Mary Martin.

LAND AND SHORE OF PLENTY

The western redcedar is sometimes referred to as the tree of life; virtually no other natural resource had so many uses for the region’s first inhabitants. Easy to split, naturally resistant to rot, and aromatic, the bark and wood of the redcedar (and of the yellow-cedar) lent themselves to a comprehensive list of applications, including building construction, clothing, fishing and hunting gear, transportation, burial needs, and the arts. Waterproof capes, hats, mats, and baskets were woven from long strips of the pliable inner bark. Shelters, ranging from enormous multi-family houses to small temporary structures, were constructed from cedar posts, beams, and planks. Canoes—from small, shallow crafts that a woman might use in calm waters to gather clover roots to whaling vessels that could hold crews of eight men—were carved from single cedar trunks. Watertight containers used for storage and cooking were fashioned from thin slabs of cedar that were steamed, scored, and bent into boxes. From the everyday to the extraordinary, the cedar tree provided so much.

Bark harvesting traditionally happened in the spring when the sap was flowing. Although they had larger, permanent village sites, native people moved throughout their territory as the natural resources they relied on came into season. In February, the Herring Spawn Moon marked the end of winter. The Nuu-chah-nulth moved from their winter villages to fishing stations where great schools of herring swam close to shore to spawn. Using large rakes, people scooped herring from the water and dried them for later use. They also strung hemlock boughs or fronds of giant kelp in the water to catch the sticky spawn.

Spring was also when the year’s fresh greens, such as the new shoots of the salmonberry bush, were harvested. In early summer, the fat orange-red salmonberries added vitamin C and some sweetness to people’s diets. Other edible berries ripened successively through the year: thimbleberry, red huckleberry, blueberry, cynamocka (evergreen huckleberry), and salal.

From the time that creamy-white herring milt clouded coastal waters in the spring to the day the last slab of salmon was dried and stored late in the fall, the Yuu-cluth-aht and Tla-o-qui-aht people crisscrossed their territories, harvesting, fishing, and hunting for the food that fulfilled their immediate and wintertime needs. Some harvesting sites were located on and near Long Beach. Plants for food, medicine, and other uses were gathered from the forests fringing the shoreline. Seafood, including razor clams, urchins, chitons, snails, and crabs, was abundant along the beach, on rocky outcrops and in tidal pools. Salmon trolling was good near shore, particularly around small islets and rocky headlands like those at Gowlland Rocks or Box Island in Schooner Cove. Halibut, seals, sea lions, and rockfish all were harvested within sight of Long Beach and its associated villages. Hunted whales were brought ashore to protected areas of the beach, and lookouts were ever vigilant for drift whales, a much-valued natural gift from the sea. (One of the battles in the Hisawistaht–Tla-o-qui-aht war was instigated by an argument over who had the rights to a drift whale that had come ashore.)

Across the peninsula, the waters of Grice Bay provided access to interior salmon streams as well as to great flocks of shorebirds and waterfowl that dwelt in the mudflat habitat.

While the Nuu-chah-nulth harvested a bounty of resources from the forest and foreshore, they were also a highly maritime culture, travelling great distances by canoe, often on the open ocean, to trade with and visit others and, perhaps most famously, to hunt whales.

THE WHALERS

All First Nations within Nuu-chah-nulth territory are traditionally nations of whalers. The expedition to intercept, kill, and tow home a whale from a canoe on the open ocean was as pivotal an annual harvesting event as it was perilous.

Preparation began during the winter, when the Nuu-chah-nulth stayed close to their main village sites, living off stored food and whatever the occasional hunting or fishing foray turned up. Much of this time was spent carving and repairing canoes and paddles, twining long lengths of cedar and sinew into rope, and crafting the all-important harpoons.

Before Europeans brought iron to the coast, hunters made harpoon tips from the shells of large mussels (now called California mussels, these can be longer than a human hand). These were bound with sinew and cemented with spruce gum to a two-part spearhead made of bone or elk antler. It seems inconceivable that mussel shell could be sharp enough to pierce the leathery hide of a whale, but each shell was carefully and precisely ground with sharpening stones to a near-razor-thin edge.

The next step was to prepare the crew and their families. Among the Nuu-chah-nulth, there were few honours higher than being chosen “the whaler,” the man who led the hunt and threw the first harpoon. Needing great physical strength and agility, ambitious young men often turned to supernatural aid—prayer, fasting, and other rituals—to gain the power necessary to become a great whaler. Such exacting preparation was essential: these men were hunting animals longer than a transit bus and as massive as six male African elephants.

Once materially, physically, and spiritually ready, the hunters embarked on the mission, with several canoes travelling together to share the dangerous work. Far out on the water, they watched for the telltale spouts of their prey, usually humpback whales. Once a whale was spotted, the hunters moved into position. The lead canoe moved to the left side of the whale so that the whaler could plunge in the harpoon near the left pectoral fin when the animal rose for a breath. If the hit was on target, the men in the stern quickly manoeuvred the canoe away from the whale’s thrashing tail, while the men in the bow released lines to which inflated sealskin floats were attached. When the whale rose again, another harpoon was thrown, tied with more line and floats. As the whale tired, the canoe moved in closer and the crew threw lances to finish the job. The final task was for one of the crew to dive into the water and sew the whale’s mouth shut to prevent the body from filling with water and sinking as it was towed to shore.

Butchering the animal was as infused with ritual as the preparation before the hunt. Meat was divided among the crew and villagers according to a strict protocol. The blubber was boiled in wooden boxes and the oil skimmed off and stored in bags made from whale stomachs and bladders. The cooked blubber, as well as the flesh of the whale, was sun-dried or smoked and stored for later consumption. Sinew, bone, and baleen were also used.

A successful hunt topped up larders, but for the Nuu-chah-nulth, the very act meant so much more. Whaling was also about culture, social organization, and tradition.

A Resilient People

For at least half of the ten thousand years it has taken the coastal rainforest to evolve into its current state, the forests and waters of the Long Beach area have supported a human population. Those who have survived and thrived through the cycles of ecological change, not to mention through the much shorter but much more devastating contact with Europeans, are a testament to perseverance and the ability to adapt as the world around them has changed.

Native people were the first residents and stewards here. Today, they are still writing their stories on Long Beach forests and shores.

_fmt.jpeg)

Through the work of Jim Darling and others, it is now known that certain whales always return to the Long Beach area and that some stay throughout the year.