BAREFOOT BOYS PLAY SOCCER in a dusty village in South Africa. The village is far from big towns, like East London. And further still from the cities of Cape Town or Johannesburg. The village is on flat, dry land. Beyond the village is the bundu: that wild and dark place.

School is over and the boys have herded the cows home from their grazing. Now, as the sun goes down, the boys are free to play. They play with an old tennis ball. The dirt field they play on is hard and the grass is worn out. No rains have fallen for over a year.

Dogs sometimes run on to the field to pinch their ball. It is tricky playing soccer with a tennis ball and dogs yapping at your heels.

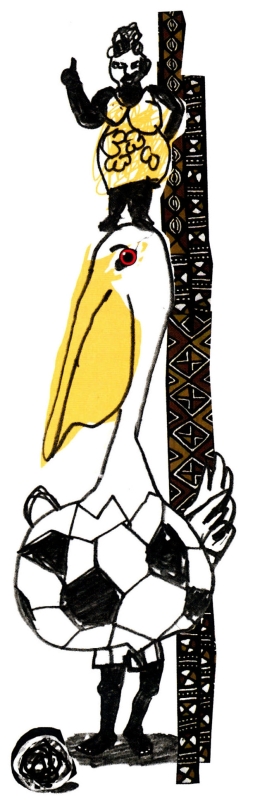

A boy called Pelé flips himself backwards and flicks his feet up for a bicycle kick. The ball flies high over the goal. Pelé lands in the dirt.

Another boy called Long Foot teases him:

– Pelican, Pelican, you think you can fly with your feet in the sky?

The other boys laugh at Pelé as he picks himself up and smacks the dust off his shorts.

Pelé’s father named him after the Brazilian soccer god, Pelé, master of the bicycle kick.

On the first day of schooling years ago his fat-bottomed teacher had said:

– Pelé? Pelé? What kind of monkey name is Pelé? It is not a South African name.

His teacher, she is clever. They have to remember all the things she teaches them as they have no books in school. They have no paper to write on. They write with chalk on a slate. When the slate is full they rub out the chalk.

His teacher knows all about science (that a feather and a stone fall at the same speed in a vacuum) and about history (that Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in jail so all South Africans, black and white, would be equal in the eyes of the law). But she knows zero about soccer.

– I will call you Pelican, his teacher had mocked.

He is 11 now, and still the boys call him by this seabird name.

One night Pelé and the barefoot soccer boys sit on the sand under the stars watching his grandfather’s TV wired to a motorcar battery. On the TV Bafana Bafana, the South African soccer squad, play on a grass field.

His grandfather sits on the back seat from a gutted, long-dead motorcar. His hair is gone and so is his left hand. He sips his beer from a bottle. Sometimes his grandfather lets Pelé sip the foam off his beer. Pelé loves his grandfather, his Tat’omkhulu.

Other old men sit on old beer crates. From the sky, through the eyes of flapping Hadeda, the motorcar seat is a goal and his grandfather the goalkeeper. The old men are the sweepers and the scattered boys (their faces as close to the TV as a dog’s feet to a fire) are the forwards.

But where are the midfielders? In the village there are no fathers or young men. All the fathers and young men are far away in Johannesburg, down the mines. Their job is to dig up gold for the moneymen. Pelé sees his father once a year, when he comes home for Christmas. He comes with beautiful cloth for his wife and a football or a book for him.

In this TV game no dogs run onto the field to hassle Bafana Bafana. All the whistling, jiving fans are behind a high fence.

Pelé would give his eyeteeth to be there, in the stadium, a stone’s throw from his heroes, floating on the whistles of the fans.

How can his mother go on stirring her pot inside their clay, zinc-roofed house? The old men (mumbling their mantra: a beautiful woman is medicine for the creaking bones) beg her to come out. But she just shakes her head. Men are fools to stare after a ball for so long.

Yet this is Pelé’s favourite thing in the world: sitting in front of the TV with his grandfather, watching Bafana Bafana, The Boys, The Boys, weave their foot magic.

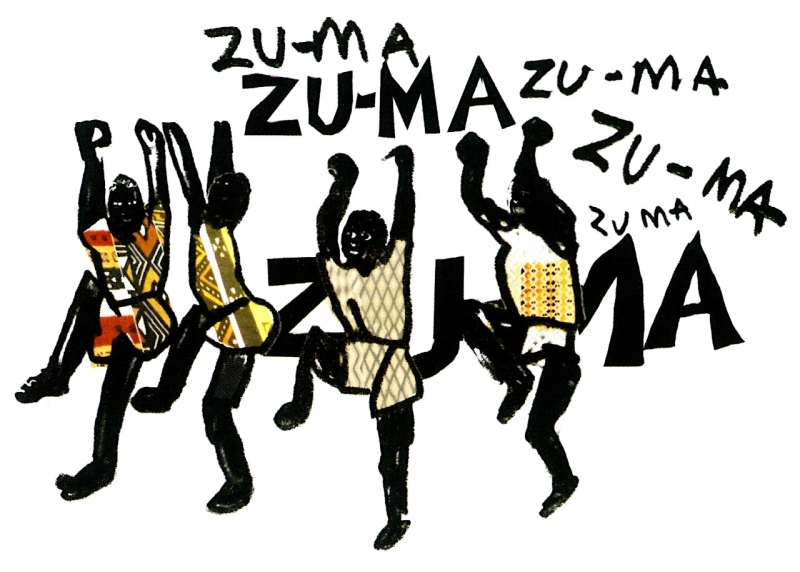

On the TV a high ball comes towards Pelé’s hero, Sibusiso Zuma. Pelé’s heart drums. Zuma kicks his feet up high like a dancing African warrior. A bicycle kick! The ball zooms into the goal.

Old men and boys jump up to dance a jiving, high-stepping dance with fists waving in the air. As they dance they chant:

– Zu-ma, Zu-ma, Zu-ma.

His grandfather gulps down his beer, tosses away the bottle and joins in. In his good hand he holds his hardwood fighting stick. He jabs it at the foes of Bafana Bafana. Let them cower. Let them beg for mercy. For a moment he forgets he is no longer a young man. He forgets that women no longer scatter in awe when he stamps his feet in the dust and shakes his fighting stick at the sky. Then he flops down, spent. He winks at Pelé.

Before Pelé can catch the words, they fall out of his mouth:

– One day I will see Bafana Bafana play live.

The boys laugh like cackling hyenas at the fool thing he has said for all the world to hear. The old men giggle at his cockiness.

– Pelican, Pelican, Long Foot baits him. You are just a poor boy. You have no shoes, never mind a bicycle. How will a no-shoe boy find the money for a ticket to see Bafana Bafana? How will a no-bicycle boy travel so far?

Other boys call out: Bafana Bafana, they play in Cape Town. Bafana Bafana, they play overseas.

Pelé bows his head in shame, for it is true that he has no shoes and no bicycle.

After the game is over the old men go to tell their wives how Bafana Bafana played like young warriors, and the boys go to tell the girls about Pelé’s crazy dream.

Pelé’s grandfather says to Pelé:

– My boy, do not be ashamed. A dream is a magic thing. You must go to Old Jamani. He deals in dreams.

Old Jamani, the medicine man, wears a tatty leopard skin. He has sharp teeth like the canines of a dog. He is forever flicking flies away with his flywhisk. He can cure you. He can talk to animals. It is whispered among the boys in the village that Old Jamani’s skinny goat was once a naughty boy he put a spell on.

– I am scared of him.

– You study hard at school and you listen to your mother, Pelé. You need not fear the wise old man.

– I am scared of the bundu animals.

Old Jamani lives all alone in a hut on a hill at the far end of the bundu. Fearsome animals such as Jackal lurk in the bundu.

– If you whistle you need have no fear of the animals, his grandfather tells him.

– I will go.

If he survives the journey through the dark bundu then he will have to beg Old Jamani to cast his bones for him. The old men of the village say that if Old Jamani throws bones and shells down in the dirt he can tell you the future. And he can tell you if your dream is good or evil.

Is my dream a good dream? Pelé wonders as

he whistles along the path to the bundu.

Pelé sees neither hide nor hair of animals in the bundu. He wonders if his grandfather’s trick works, or if all the animals have been hunted by gunmen.

At the top of the hill, Old Jamani is sitting on his doorstep milking a goat. Pelé feels Old Jamani’s eyes spear through him. He shivers.

– You have come about a dream, young Pelé.

How does the old man know my name? Pelé wonders.

– I see your father in you. He too was a dreamer.

Pelé wonders if his father still dreams during the long, dark hours he spends down the mines. His grandfather still has a dream.

– I want to see Bafana Bafana play live.

– Yo, yo, yo. That is a hard dream for a poor, barefoot boy.

Pelé’s heart drops like a stone.

– Yet it is a good dream. And a few hard dreams do come true. A boy born in a clay hut not far from here dared to fight a giant python to free his people.

Pelé senses that the python-fighting boy was none other than Nelson Mandela.

– Let me throw the bones, says Old Jamani.

Old Jamani takes a fistful of bones and shells from his pocket and rattles them in his hands. The tied-up goat jiggles its feet at the sound.

Pelé wonders what highjinksy mischief that boy got up to for Jamani to trap him inside the goat.

Jamani breathes over the clinking bones and shells. Then he throws them.

Pelé can see no pattern to the way they fall. He was hoping they would form a picture, like the dots you could join up in the colouring-in book his father once got for him in Johannesburg.

Old Jamani spits out his findings:

– The wild animals will give you talismans.

– Talismans?

– Magical things to help you on your long journey. There are dangers in the place you are going to that you cannot fight with your slingshot.

– And where will I find the wild animals?

– Just walk and they will find you.

– How will I talk to them?

– Now that is my gift to you, Pelé. Go well, Young Dreamer.

– Stay well, Wise Old Man.

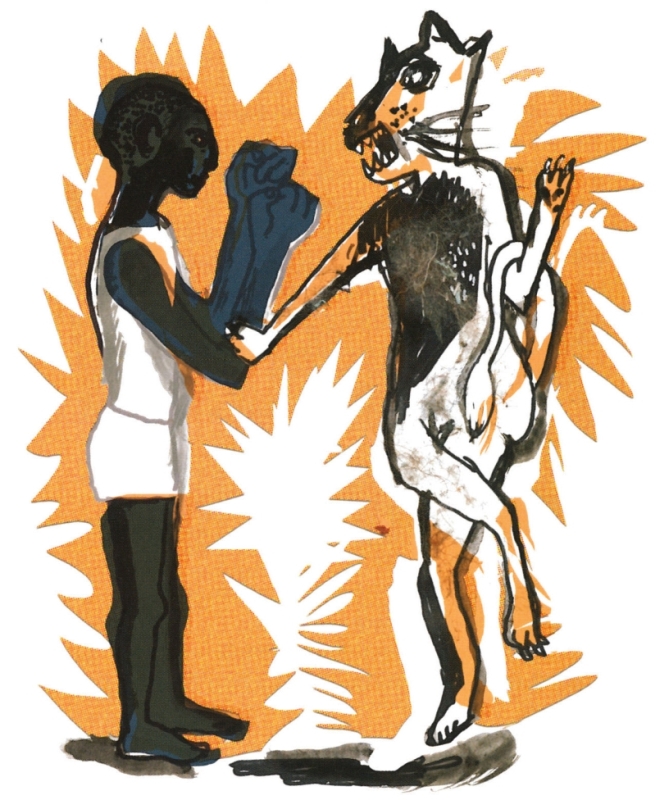

On the path down through the bundu to the village a cat half the size of a lion glides out of shadow. Pelé almost jumps out of his skin.

– Jamani told me about your wild dream, Pelé, the cat murmurs in a lazy voice. Though, I must say, I did not imagine you’d be so jumpy.

Pelé bends his fingers into puny fists.

– What kind of wild cat are you?

– I am Lynx. To follow this dream of yours calls for guts and the hissing fury of a caged lynx.

Pelé thinks: Maybe I should stay and herd cows with the other boys.

– Before you go, please do me a favour. I have a niggling, nagging tooth. Won’t you yank it out?

Pelé’s heart drums but he wants to show Lynx he does have guts. He puts his fingers into Lynx’s razor-toothed mouth and pulls at the bad tooth.

Now the tooth lies in Pelé’s hand. The gum end is bloody.

– Hmmm! How good that feels. If ever you’re dead scared and need to be plucky ... hold my tooth in your fist. But remember: its magic will work just once.

Pelé puts the tooth in the good pocket of his tatty shorts. His other pocket has a hole in it.

He bows to Lynx as she lopes away. The last thing Pelé sees of Lynx is the tufts of hair on the ends of her ears.

As Pelé crosses a river on a wonky log, a giant lizard puts his head out of the water. Pelé teeters on the log. The lizard is the size of a small crocodile.

– What kind of lizard are you? Pelé cries out.

– I’m Leguaan, Pelé. Jamani told me about your fanciful dream, Leguaan says as his tongue slides in and out. Though, I must say, I did not imagine you would be so skinny. A hard journey lies ahead of you.

Pelé thinks: Maybe I should stay and just watch Bafana Bafana on my grandfather’s TV.

– Before you go, please do me a favour. I have a loose, lagging claw on my back foot that bothers me. Won’t you tug it off?

Pelé tugs the bothersome claw from Leguaan’s scaly foot.

– Aaaah! How soothing that is. If ever you’re being hunted and you need to swim swiftly ... put my claw under your tongue. But remember: its magic will work just once.

Pelé puts the claw in his good pocket, where it scratches and jars against the tooth.

He bows as Leguaan zigzags over the water. The last thing Pelé sees of Leguaan is the fiery flicker of his tongue.

Pelé walks on along the path through the bundu until Jackal slinks out of a hole, all sleek and lithe. Pelé has seen Jackal before: lurking about the rat-infested dump behind the village.

Pelé is pee-spit scared of Jackal. His grandfather had told him that Jackal had bitten the fingers off his stubby hand.

What Pelé does not know is that his grandfather’s fingers got caught in a machine on the mines. After that he lost his job and came to the village to sit on his red motorcar seat.

And one day Nelson Mandela came out of the glaring sun to shake his good hand and sit down beside him.

The other old men tease his grandfather and say it was a dream. But ever since then his grandfather has not let anyone sit down next to him on the motorcar seat. If Mandela comes again, there must be a free seat for him.

– Don’t be afraid. I’m not hunting you. Jamani told me about your tricky dream, Jackal says in a sly, silky voice. Though, I must say, I did not imagine you’d be so young.

– Do you have to be old and wise to dream? Pelé says in a voice that quivers and dithers.

– Well, you have to be old to dream wisely.

Pelé thinks of his grandfather pouring a glass of beer for Mandela every day in the hope that one day he will sit down beside him again. By the time the sun goes down, the beer has gone flat and zizzing flies drown in it. How wise is such a dream?

– You are a clever boy, Pelé. You have learnt the things your teacher taught you. But to follow your dream to the end you’ll need the cunning of a jackal.

Pelé thinks: Maybe I should stay and play soccer with a tennis ball.

– Before you go, I need you to do me a favour. I have a tickling, teasing hair in my ear. Won’t you pull it out?

Pelé pulls the ticklish hair from Jackal’s ear.

– Yai, yai, yai! How free I feel. If ever you’re cornered and need to think fast ... lick this hair and put it behind your ear. But remember: its magic will work just once.

Pelé puts the hair in his good pocket, where it dances between killer tooth and snagging claw.

He bows to Jackal as he skulks into shadow. The last thing Pelé sees of Jackal is the flick of his furry tail.

Pelé comes out of the bundu. The path is flat now and he can see the village ahead when he hears a whisper.

– Hey you. Dream boy.

Pelé looks around but all he sees is a lonely coral tree with a few flaming orange flowers. Then he sees that one of the knots on the bark of the tree is in fact an eye. The eye swivels, now looking up at the sky, now down at him. It is Chameleon, camouflaged in the same sandy colour as the bark of the tree. The last time Pelé saw him he was all aloe green.

– Hello, Chameleon.

– Jamani told me about your tall dream, Chameleon whispers in a wispy voice. Though, I must say, I did not imagine you’d throw such a flat, stark shadow.

Pelé thinks: Maybe I should stay in my mother’s hut with her smoking, three-legged pot and the smell of soap on her skin.

– Before you go, please do me a favour. The tip of my tail is dangling and dying after the butcherbird pecked at me. Won’t you twist it off?

Pelé pinches the dangling tip of Chameleon’s tail in his fingers and twists it off.

Chameleon shoots out his long, pink tongue with glee.

– Now my tail will heal. If ever you’re trapped and need to vanish ... just rub the tip of my tail between your fingers. But remember: its magic will work just once.

Pelé puts the tail tip in his good pocket, where it tangles and tangos with Jackal’s hair.

Chameleon winds up his long tongue. The last thing Pelé sees of Chameleon as he fades out is his beady eye. Then Chameleon shuts his eyelids ... and he’s gone.

On the edge of the village he hears Hadeda cry out to him: ha ha haaaa.

The dull-feathered bird is sitting on one of the goal posts.

– Hello, Hadeda.

– Hello, Pelé. Jamani told me about your crazy dream. Though I did not imagine you’d be so flat-footed. Ha ha haaaa.

Pelé thinks: Maybe I should just stay and make play oxen out of clay.

– Before you go, I need you to do me a favour. I have an itchy, irksome feather behind my head that I can’t scratch with my beak. Won’t you pluck it out?

Pelé plucks Hadeda’s restless feather.

– Haaaa! That feels good. If ever you need to fly like a bird ... slide this feather into your hair and you’ll fly as far as a man can throw a spear.

How Pelé would love to fly now over his grandfather’s red motorcar seat and call down to him and the other boys. Pelé laughs at the thought of them running after him and yelling: Au! Au! Au! Pelican can indeed fly through the sky!

As if Hadeda reads his mind, she warns Pelé:

– But remember: its magic will work just once. So do not use it lightly.

Then Hadeda cries ha ha haaaa and flies towards the rusty roof of the old tin church.

Pelé puts the feather in his good pocket, where it hovers over tooth, claw, hair and tail tip. Now he has all the charms he’ll need for his trip.

The last thing Pelé sees of Hadeda is a glint of green in her feathers.

Pelé’s mother cries when she hears he plans to go to Cape Town to see Bafana Bafana play.

– Aaaai! I will not let you go. You will still sleep in my hut for another few years, until it is time for you to go into the bundu to become a man.

But in the night Old Jamani puts a dream in her head of Pelé bird-flying high over a big town. In the dream deadly gangboys called tsotsis shoot stones at her son with their slingshots. They want to make him bleed. The stones whistle through the sky, but none hit him. They fall into the hands of Old Jamani who rattles them and then breathes over them. He casts the stones and they turn into stray dogs. The dogs bark and bite at the heels of the tsotsis as they run away.

In the morning his mother tells Pelé:

– You may go. Old Jamani gave me a sign. And yet I fear for you, my only son. I fear you will get lost. I fear evil will catch you. I fear you will never again sleep in my hut.

Pelé’s grandfather gives him his old, black bicycle with fat tyres and no gears. And he gives him his good shoes. Italian shoes he got in Johannesburg long ago. They are too long for Pelé’s feet and he puts newspaper in the toes to make them fit.

His mother gives him the money she’d been saving for a flowery dress.

Pelé has never held so much money in his hands. Yet it is still too little money for a bus ticket to Cape Town, or for a ticket to see Bafana Bafana play.

All the villagers gather to bid farewell to Pelé. The bicycle is too high for him. He has to stand to pedal.

– Go well, his mother cries.

She walks to her hut to hide her sorrow.

– Go well, his grandfather calls.

The last thing he sees is the sun glancing off his grandfather’s head. A head as bald as their old tennis ball.

Pelé is lucky, for the road down to the sea winds downhill. Even so, he cycles all day to get to East London.

East London is the biggest town he has ever seen, yet they tell him it is small compared to Cape Town.

With some of his mother’s money he gets hot fish and chips. He finds a bench by the sea to sit on and eat his fish and chips. It is the first time he has ever had fish. The only thing he has had from the sea is the water his grandfather once took from the sea in a Coca-Cola bottle. The villagers believe sea water is magical and can cure you if you fall ill.

From his bench he can see penguins in a tidal pool and further out, past the rocks, he can see surfers. He has never seen penguins or surfers before. Yo! The penguins cannot fly. They plod as flat-footedly as him over the rocks. And yet, under water, they do fly. With a flap of their wings they glide and curve and swerve like underwater surfers.

Pelé tells the penguins of his Bafana Bafana dream.

The penguins hee haw at his foolhardy dream like long-toothed donkeys.

As the sun goes down Pelé drifts off to sleep on the bench.

A bulky policeman shakes Pelé awake.

– You can’t sleep here, the policeman says in a gruff voice.

Pelé jumps to his feet. He shivers. The world is yellow and cold under the streetlamps.

– This beachfront is for holidaymakers, not runaway rascals.

Pelé looks around for his bicycle. It is gone.

– Run along, or I’ll put you in the back of the van.

Pelé sees a big dog in a cage in the van barking his lynxy teeth at him:

– Run, boy, run.

Pelé runs. He turns his head just once to see the policeman bang the dog’s cage.

For a long time the dog’s warning echoes in his ears:

– Run, boy, run.

All night Pelé walks along the streets of East London. He is sad his grandfather’s bicycle is gone and he is scared of the police. Maybe next time they will put him in jail.

As the sun comes up he sees women set up their rickety stands. Some sell fruit, others shampoo and combs, still others sunglasses.

At a taxi rank he asks a man with a bongo-drum belly if any of the taxis go to Cape Town.

– I go that way ... as far as Port Elizabeth. Do you have money?

Pelé takes one of the notes from his pocket.

– That is not enough for a seat in my taxi ... but I will let you ride up on the roof rack with the suitcases, boxes and chickens. You must keep your head down. It is against the law to roof ride, and if the police catch me my licence will be gone, one-time.

He snaps his fingers so Pelé can see how fast his licence can be gone.

Up on the roof, Pelé curls up and falls asleep. Not even the cackling of the chickens keeps him from dreaming. In his dreams he is playing for Bafana Bafana. He is no flat-footed boy who fumbles the ball. Zuma sends him a cross and he heads it into the goal. He flips his shirt up over his head to reveal the words:

Where are you, my father?

He wakes to discover they are in Port Elizabeth, another town on the sea. Seagulls fly hard into the wind off the sea, yet they hover in one spot just above him.

Pelé comes down from the taxi roof. The taximan laughs at the sight of Pelé all dusty, with chicken feathers in his hair. He points Pelé to where the big bus to Cape Town is standing.

The last Pelé sees of the taximan is his amused, white teeth.

The busdriver is snoring under his handkerchief.

– Please Mister, may I get a ride to Cape Town?

The busdriver lifts a corner of his handkerchief. He squints and blinks a few times to focus. All he sees is a dirty boy.

– Just to Cape Town, or all the way to New York?

The busdriver laughs at his joke. Ha ha ha.

– Have you booked?

– No, but the bus is empty.

– Don’t you get cocky with me, boy.

Pelé hands the busdriver the last of his money.

– I will give you a ride as far as your money goes.

– When do we go?

– When the bus is full. Ha ha ha.

With that the busdriver puts his handkerchief over his head again. There is a picture on the handkerchief of a man with smiling teeth and long dreadlocks. Underneath it says: Bob Marley. Pelé’s father would always smile and turn up the radio when a Bob Marley song came on. He would drum his fingers on a box, or an upturned pot. Pelé loved to see his father so upbeat. That is the magic of Bob Marley.

Then Pelé thinks this thought: Maybe it was my father’s dream to play in a band, rather than dig up gold for the moneymen.

The bus goes for miles and miles and miles. Pelé falls into a deep, dreamless sleep.

The bus stops. There is no town in sight.

– Out you hop, the busdriver commands. Unless you have other money hidden in your pockets.

– I have no hideaway money. Can I walk to Cape Town from here?

All the travellers on the bus laugh and shake their heads. They know it is still far over a hundred miles to Cape Town ... far too far for a boy to walk.

An old woman in a colourful head cloth says to the busdriver:

– Let the boy stay on as far as I go. I’ll pay for him. You can’t put a boy out on the road.

The busdriver smiles slyly. A good trick. He had guessed someone would feel sorry for the boy and fork out the money. Ha ha ha.

The bus stops again. They all get out of the bus.

It is not as Pelé pictured Cape Town. A flat-topped mountain in the distance and rows and rows of tin shacks. Dust and smoke hang over the shacks. Stray dogs beg from a woman selling chicken feet. He had heard Cape Town was beautiful.

But where is the sea? Where are the fruit trees?

– Is this Cape Town? he asks the kind woman with the colourful head cloth.

– No, this is Langa.

– So where is Cape Town?

– It is at the foot of that flat mountain they call Table Mountain.

– So far.

– Good luck. Here is a banana for you.

She tugs a banana from a bunch.

– Go well, my boy.

– Stay well, mother. You have been too kind.

The last Pelé sees of her is the bunch of vivid yellow bananas balancing on top of the suitcase balancing on top of the box balancing on top of her colourful head cloth as she goes on bandy legs.

– How do I get to Cape Town? Pelé asks the seller of chicken feet with a pink, zigzag scar on her hand.

– You can get a taxi.

– I have no money.

– Yo, yo. I am sorry for you. No money, no taxi.

She gives Pelé a chicken foot.

– Forgive me. I am curious. How did you get the scar?

– It was the tsotsis. They flicked off my head cloth to pinch the money I hid under it. When I put out my hand to cover up my head they stabbed me.

– The tsotsis?

– Beware of the tsotsis.

Pelé puts the banana in his pocket and gnaws at the chicken foot as he sets out on the long walk. The last thing he sees of the seller of chicken feet is her flinging a gnawed foot to a bony, begging dog.

Pelé wanders through alleys, always keeping Table Mountain in sight.

As he comes around a blind corner tsotsis ambush him with ratty eyes and stony fists.

Pelé drops his chicken foot out of fear.

– Hand us your money, lost boy, the tsotsi chief commands.

– I have no money, Pelé cries.

A buzzardy dog slinks out of shadow to sniff at the chicken foot.

The tsotsi chief flicks open the blade of a flick-knife.

Pelé holds out his banana as an offering. The tsotsi chief smacks it out of his hands and stomps on it. Yellow flesh squishes out.

Pelé imagines the boy stomping on his head. Fear shoots through his bones. The buzzardy dog abandons the bone to sniff Pelé’s fear. The smell of his fear lures other stray dogs out of the shadows.

– Empty your pockets, the tsotsi chief spits.

Pelé feels in his pockets. His fingers find Lynx’s tooth.

He holds it in his shaking fist. Rage burns through him and his fist forms as hard as the wood of his grandfather's fighting stick. Behind Pelé, the stray dogs now tune into the stink of the tsotsis’ hate and it sends them blood crazy. Just then Pelé yells a banshee yowl and runs at the tsotsis. The tsotsis see wildcat wildness in his eyes, and, beyond him, the jagged teeth of the dogs baying for blood. They spin on their heels and flee.

The last thing he sees is sun flashing on the blade of the flick-knife futilely flung at the dogs. Pelé feels the tooth turn to dust in his hand.

Pelé sleeps in a school playground on the sand in a play-play house. The sand smells of dog pee, but he sleeps deeply. So deeply he does not feel a raggedy hobo teasing his grandfather’s shoes off his feet.

The hobo slides his fingers into Pelé’s pockets but he finds no money. All he finds is a claw and a feather. He drops them, fearing they are some kind of juju.

Pelé does not see him hobble away, giggling to the moon. Good Italian shoes are like gold dust.

A cold wind bites Pelé’s toes. He wakes and stares at his bare feet. Where did my shoes go? Did they walk away?

On the sand he finds Leguaan’s claw and Hadeda’s feather. In a corner of his pocket he finds Jackal’s tickling hair and Chameleon’s dried-up tail tip.

Pelé goes on barefoot towards the city at the foot of the flat-topped mountain.

After a time his soles begin to hurt.

Pelé limps up a street in Cape Town. He sees things he has never seen before:

Double-decker buses.

A cable-car going up and down Table Mountain.

Buskers plucking banjos or guitars and people dropping coins in a hat at their feet.

A man tapdancing for hat money.

Pelé thinks: Maybe they would give me money if I stood on a street corner and juggled a tennis ball on my foot? But he has no tennis ball, and no hat.

Pelé walks Cape Town flat, drifting from busker to busker, beggar to beggar, to learn the ways of this hustling, jostling world.

In a cobbled square called Greenmarket Square there is a market. Stalls sell masks and beads and paintings and flywhisks and drums and carvings and shells and cloths.

He hears languages he has never heard before.

– I am from Zimbabwe, the man who sells giraffes carved out of wood tells him.

– I am from The Gambia, the man selling bangles made out of cowrie shells tells him.

– I am from Kenya, sings the woman selling cloths in all the colours of the rainbow.

This is one way to survive in Cape Town, Pelé thinks. How he wishes he had something to sell, but the good things he had are gone: his grandfather’s bicycle and his grandfather’s shoes.

In a corner of Greenmarket Square a boy is selling geckos made of wire and beads.

– My name is Toto, he chirps. You look lost.

– My name is Pelé. I am not from here.

– You hungry?

Pelé nods.

– Just follow me.

– Where do you live?

– Nowhere.

– Nowhere? Even Jackal has a hole.

– My father ran away long ago. My mother died of AIDS.

Pelé does not know what AIDS is but it sounds to him like a snake. Maybe a deadly mamba bit her.

They walk along steep streets made of stones through the Malay Quarter. The houses are painted orange and light blue and lime. Pelé has never seen such happy houses.

Then two shadowmen monkey over a wall and catch Toto. They tip him upside down and dangle him by his heels. The money Toto made selling geckos jingles in his pocket, then coins clink onto the stones. The shadowmen drop Toto, pick up the coins and pocket them. Toto stays down among his scattered geckos and puts his head between his knees so they do not see him cry.

Then the shadowmen turn on Pelé.

– Empty your pockets, boy, they snarl at him. Or we’ll rattle you too.

Pelé’s knee bones knock.

He turns his pockets inside out. The shadowmen do not see Jackal’s hair whisked away on a breeze. They do not see that Leguaan’s claw and Chameleon’s tail tip stay pinched in the hem of his pockets. All they see is Hadeda’s feather flutter down to the stones.

Pelé drops to all fours to catch the feather.

– A good luck charm, a shadowman mocks.

Pelé pockets the feather.

He calls out to Jamani:

– O Jamani, don’t let the hair get away, otherwise I’ll never see Bafana Bafana play.

The shadowmen haw haw at this.

– Hear him reel off such mumbo-jumbo.

– Who ever heard of a penniless boy at a Bafana Bafana game?

The last thing Pelé sees as the shadowmen go is the sun blink off a silver coin they spin in the air.

Pelé picks up Hadeda’s feather. The breeze carries Jackal’s whisper-thin hair back to him.

Pelé feels over the moon that Jamani heard him from afar.

– Come, let’s go eat, says Toto, rubbing away his tears.

– How will we eat if we have no money?

– Just follow me.

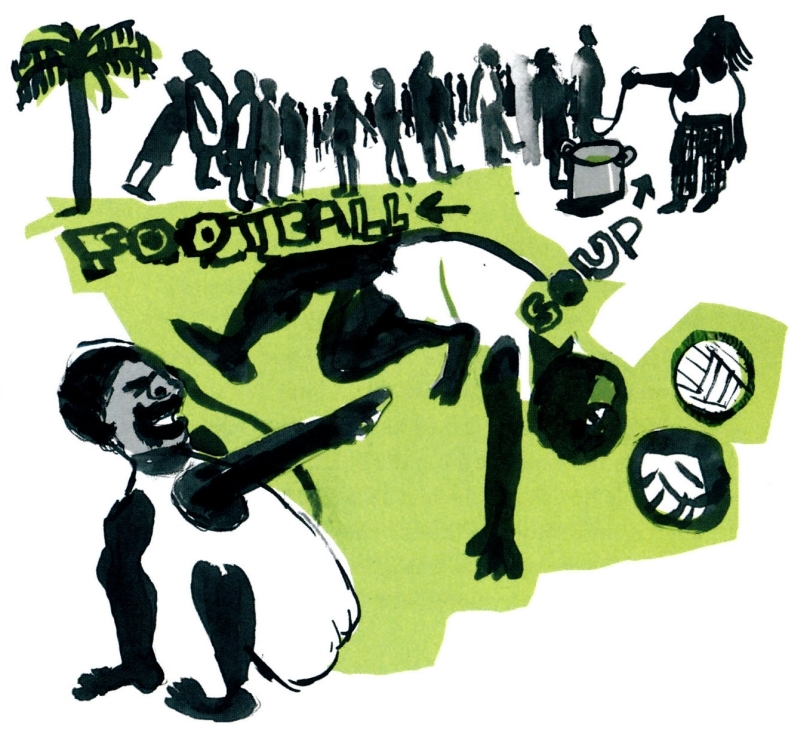

They go along a palm-lined street and come to a light-blue house. Boys line up at the door. Each boy in the line is given a cup of soup and a block of bread.

Pelé and Toto sit on the pavement in the shade of a palm. They dunk the bread in the soup and eat it. Pelé thinks, bread has never tasted so good.

Pelé and Toto look at each other and giggle at the sight of their stuffed cheeks. They feel like kings.

Afterwards they play soccer on a field in an old quarry across the road. It is the first time Pelé has played on grass.

Though his feet hurt, he goes up for the bicycle kick when Toto crosses the ball. He misses the ball and wipes out.

– You think you’re Zuma, Toto laughs.

Suddenly Pelé misses his village, even Long Foot’s mocking, and he has to squinch back his tears.

The sea is full of fish, thinks Pelé. I will catch fish and sell the fish. Toto will be amazed when I come along with money jingling in my pocket.

He goes down to Cape Town harbour. On an empty, moored fishing boat he finds a handline.

He puts no bait on the hook for he has never fished. He casts the handline from the boat.

While he dangles the line he watches tourists board a ferry out to Robben Island. They all want to see where Nelson Mandela was jailed. He would love to go but he sees the ferryman check for tickets.

A man comes along and yells:

– Hey, you no-good urchin. Get off my boat.

He shoves Pelé over the edge into the water. Pelé goes under. He madly flaps his hands and feet. Shark picks up the signal and curves towards him.

The seals sunning on the harbourside see Shark’s fin homing in on him.

They bark aarf aarf aaarf at Shark and call him a bully but they are too scared to slide in and save Pelé.

Under water, as he sinks down, down, down, Pelé sees Shark circle him with cruel, catty eyes. O Jamani, he prays. He feels in his pockets for Leguaan’s claw and slips it under his tongue. Next thing, his hands turn into lizardy claws and a leguaan’s long, whippy tail morphs out of his skin. He shoots to the surface and zigzags over the water. Shark is spooked by this. He has never seen such a strange fish: all long and eely, with feet like a turtle’s and some tatty rag about his hips.

The seals flap their flippers with glee. They have never seen Shark look bamboozled.

Pelé swims out of the harbour and across the bay to Robben Island. Now he spears like a penguin under water. Now he skims like a surfer over the surface.

As he comes to the jetty ladder, the claw melts under his tongue and his hands become the hands of a boy again.

He follows a flock of tourists onto a bus to the quarry where Nelson Mandela broke stones under the blazing African sun.

The next stop on the tour is the cell where Nelson Mandela was locked up.

B Section. Cell 5. The cell is as wide as his grandfather’s motorcar seat.

The tourists take snapshots through the bars of the cell.

The tourguide, who was himself a prisoner with Nelson Mandela on this island, tells them:

– He spent 18 of his 27 years in jail in this cell. He broke stones all day, yet they never broke him. He never gave up on his dream of seeing a free South Africa.

– Why didn’t he just swim across the sea? a tourist pipes up.

– No prisoner ever survived the swim from Robben Island to Cape Town, the tourguide tells them. The sea is ice cold, the waves are high and there are sharks. Otherwise I would have given it a shot.

The tourists laugh, so Pelé can tell it was a joke.

After the tourists go Pelé stays on alone. He stares at the grey blanket, the stool and the bucket to pee in. All he can see out of the barred window is a wall and a bit of sky.

At the jetty Pelé wants to get onto the ferry.

– Ticket, says the ferryman.

– I lost my ticket, Pelé fibs. And I have no money.

– Then you must stay on the island, with the penguins and ostriches.

The man does not laugh, so Pelé cannot tell if this is a joke or not. He walks to the end of the jetty. The tourguide’s words echo in his head: No prisoner ever survived the swim.

Pelé fishes in his pocket for Jackal’s hair. He licks it and puts it behind his ear. The hair tickles him. It is hard not to wriggle and giggle as he goes up to the ferryman again.

– Tell me, Sir, how did I get to the island if I had no ticket?

The man is stumped.

– Perhaps you think I swam?

– A skinny boy like you? No way.

The man whistles through the hole where his front teeth are gone. He gazes out over the vast sea.

Jackal’s hair fidgets and fiddles behind his ear. Pelé has to clench his teeth not to giggle.

– You may as well hop on then, says the ferryman.

As Pelé goes up the gangplank he flicks the hair away and sees it fall into the water. It dances on the surface until a fish snatches it up. Pelé sees the poor fish jumping out of the water, doing flick flacks in the air.

Pelé and Toto sleep in doorways. There is a hostel under a bridge for boys but if you sleep there you have to go to school. Though there is always the risk of being caught by the shadowmen, or being stabbed for a few rands by the tsotsis, Toto does not want to give up the freedom of the streets, or the chance to make money in the market.

Pelé forgets about catching fish. Toto teaches Pelé how to make the wire geckos they sell in the market. They have no stall. A cardboard box is their shop.

Toto finds Pelé’s dream cool. He too would love to see Bafana Bafana play.

The pennies they get from selling geckos they hide in a coffee tin beyond the soccer field, so the shadowmen do not get their hands on it. They save to get tickets to a Bafana Bafana game.

One day, when they are selling their geckos in the market, the police come. They want to catch all those who have no licence to trade, or have no papers to be in South Africa. The police have blocked all the roads running away from the square. There is no way out.

– Follow me, Pelé says to Toto. They go into a stall selling dresses and beads and hide in the curtained-off corner of the stall where girls try things on.

– They’ll find us, says Toto.

– Just take off your clothes, says Pelé.

– You crazy?

– Trust me, says Pelé (although he is not sure the magic works for two).

In a jiffy they are naked, shorts in hand. They would giggle if not for the yelling of the police and the barking of the police dogs.

Pelé digs into his shorts pocket and finds Chameleon’s tail tip. He holds Toto’s hand and rubs Chameleon’s tail tip between the thumb and forefinger of his other hand. Pelé sees fear in Toto’s eyes. He smiles at Toto as they blend with the green canvas of the stall.

The policeman who whisks the curtain open is too slow to see four floating eyes snap shut.

– Empty, the policeman yells to the others.

They see him spit on the cobbles as he lets the curtain go. The tail tip falls though Pelé’s fingers. As he searches for it down among the cobblestones his hands change from green to his skin colour. The tail is gone.

Then comes the day Pelé and Toto hear the chanting of the Bafana Bafana fans heading for the stadium.

– Bafana Bafana! cries the man selling the Cape Times on a street corner.

Bafana Bafana! The Boys, The Boys! In Cape Town! Sibusiso Zuma, MacBeth Sibaya, Siyabonga Nkosi, Bafo Biyela. The Boys!

Pelé and Toto run to dig up their tin and find it empty. Pelé drops as if shot ... or as if to bicycle kick. But this time there’s no ball, no money. Just a feather. And how can you fly a dream on a feather? The shadowmen had somehow smelt out their money like a shark smelling blood. The bastards.

Downcast, Pelé and Toto follow the milling fans to the stadium. Hordes of smiling, jiving, whistling folk, black and white. Men with beer cans in hand shout playful insults at the rival fans from Europe. You can tell by their smiles they all have tickets.

All line up to go through the gates. Pelé and Toto stand at the end of a line. By the time they get to the gate there is a roar coming from inside the stadium.

– Tickets, the gateman demands.

– We have no ticket.

– Then voetsek.

He whisks his hands at them as if shooing away begging dogs.

Pelé uses his last talisman. He puts Hadeda’s feather in his hair and holds Toto by the hand. Toto wonders if they will vanish again. Instead their soles peel away from the paving. They fly over amazed heads and flashing cameras. They laugh at the gaping gob of the gateman. They fly up over the stadium wall, over the heads of fans in the high pigeon seats, as far as a man can throw a spear. The flightless penguin has been wizarded into a pelican. Is this not magic?

They land on the grass pitch.

The stadium is a caterwauling circus of whistling and singing and dancing to the rhythms of drums.

– Hey, you two, how’d you get over the wire? a policeman yells at them.

Pelé turns to see that all the fans are behind a high fence.

Another policeman shouts:

– Stand still now. The Boys are coming!

– BAFANA BAFANA! the crowd yawps.

The drums go berserk. Fans dance and whistle as if the world is about to end.

As Bafana Bafana run on, Sibusiso Zuma winks at Pelé and Toto. Toto punches Pelé on the arm with glee. Pelé just stands gaping at his hero.

A TV camera picks up Zuma. The camera focuses on him juggling a ball on his feet, then on his head, then on his feet again. Then Zuma kicks the ball and the camera swings to follow its flight to where it lands at the feet of Pelé and Toto.

Meanwhile, back in Pelé’s village, barefoot boys are watching on a TV hooked up to a motorcar battery.

– Hey, isn’t that Pelican? the boys cry out, jabbing fingers at the TV.

Pelé’s grandfather leaps to his feet and jabs his fighting stick at the sky.

– Hujuju, he cries. Pelé did it. By god, he did it. I told him a dream is a magic thing.

On TV Pelé snaps out of his daze and kicks the ball to Zuma. Zuma catches it on his head then flicks his foot up to bicycle kick it over the high fence as an offering to the fans.

Long Foot is dead quiet. The old men shake their heads in wonder.

Pelé’s grandfather sends a boy to fetch Pelé’s mother from her hut. She is just in time to see one of the policemen open a gate in the high fence and bid Pelé and Toto go to their seats. The policeman is pointing up at the stands. Pelé turns to stare into the eye of the camera again and waves to all in his village.

Pelé’s mother bangs a spoon against a pan. Her boy has become a young man.

The villagers, Long Foot among them, jump up and wave madly at the TV.

Far to the north, in Johannesburg, Pelé’s father is tuned into the game on TV along with all the other miners. They have soaped off the dirt and sweat. They have cold beers in their hands. There is no way the mine bosses can make them go down the mines while Bafana Bafana play.

– Hey, that’s my boy on TV. My son, Pelé!

He is up on his feet, his beer froth overflowing. All the men cheer. It is not a small thing that a man’s son is on TV for all the world to see.

Pelé’s father stands until the men whistle at him to sit. The game is about to begin.

Pelé’s father can picture the scene in the village of his boyhood and daydreaming. His beautiful wife shaking her head at the antics of boys and men from the door of their hut. His father on the motorcar seat. Old men on boxes. Boys sitting cross-legged in the dust. All the village boys other than his son.

How on earth did he get to Cape Town?

How he wishes he was home ...

And then Zuma scores from way out. There’s an awed hiatus in the room. A sucking of air deep into the lungs. Then the world tilts.

– ZUMA! ZUMA! ZUMA!

All the folk in the village yell to the sky.

Then Pelé’s grandfather catches Pelé’s mother with his good hand and spins her till her skirt flowers out like a hibiscus. The old men swivel their hips and feet about. The boys cartwheel and cavort.

And then, lo and behold, Old Jamani comes shuffling along, tugging a skinny goat by a string and waving a flywhisk. The world is standing on its head. Old Jamani tethers his goat to the coral tree. The village dogs whine at the sight of this jiggle-footed goat.

Pelé’s grandfather signals Old Jamani to sit on the motorcar seat.

The old men gasp as the medicine man sits on Mandela’s half. This is an honour indeed.

Pelé’s grandfather tips out Mandela’s flat, fly-spiced glass of beer, dousing poor Chameleon who is camouflaged the colour of sand. Then he sits down beside Old Jamani.

Old Jamani picks up the sopping chameleon and puts him on his shoulder where he begins to blur into leopard skin.

The boys see that they need not be scared of this medicine man. He is no spell-casting wizard. His magic is good. His goat is just a goat. And his leopard-skin coat is moth-eaten.

Pelé’s grandfather pours Old Jamani half the beer from his bottle.

Lynx and Jackal peep out from behind a coral tree. For as long as the game goes on they forget they are old foes. Leguaan hovers unseen in the shadows.

And up among the orange flowers of the coral tree, just as Zuma scores from a bicycle kick, Hadeda calls: ha ha haaaa.