The political landscape of Europe

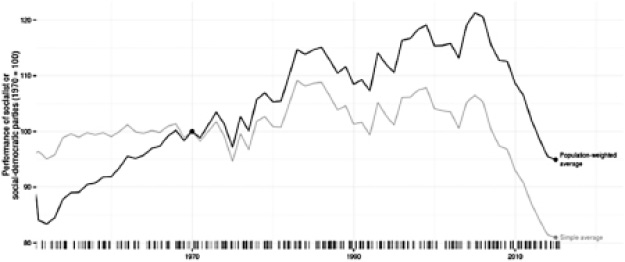

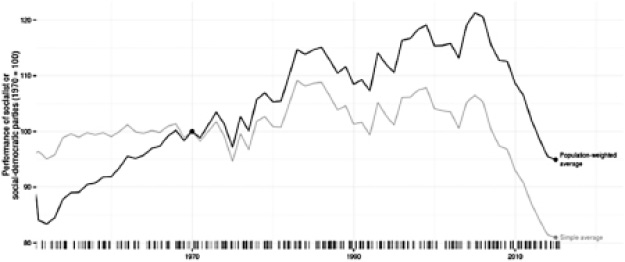

Since the financial crisis in 2008–9, centre-left parties have been performing poorly in almost every EU member state. The present electoral map is bleak; as Figure 1.1 of EU15 countries since 1946 demonstrates, the electoral position of centre-left parties has been in dramatic decline since the late 2000s having risen fairly consistently throughout the postwar years.

The period of electoral decline seems, nonetheless, to have preceded the financial crisis; since the early 1970s, social democracy has undergone a period of ‘significant electoral retreat’ which worsened during the 2000s.1 Although the vote share of centre-left parties had eroded, many experts resisted the claim that social democracy was in a state of terminal decline: after all, centre-left parties in most countries were one of two dominant political formations and therefore likely to gain support to form a government at some point in the near future (Moschonas, 2008). More recent trends indicate this may be rather optimistic: even in the UK, where the Labour party’s position is entrenched by the first-past-the-post electoral system, there are indications that the traditional two-party system is gradually breaking down.

Figure 1.1 The Performance of Social Democratic Parties in Western Europe2

Table 1.2 Electoral Performance of Socialist Parties in Western Europe (Legislative Elections)

In recent years, social democrats in western Europe have either been in government, where they have experienced record unpopularity such as in France, or they have been weak junior members of coalition governments with limited room for political manoeuvre, such as Germany and the Netherlands. The French socialists have been divided since François Hollande’s presidential victory in 2011: the traditional left in the party sought to put forward a radical alternative to austerity based on higher personal and corporate taxation, while the reformists now backed by President Hollande battled to reform France’s apparently arcane labour regulations and introduce tighter controls on public spending.3 This is a reaction to the deep structural problems afflicting the French economy; nonetheless, Hollande is the most unpopular president in France since polling began.4

In the Netherlands, the PvDA has had to cope with much greater electoral volatility as the result of new economic and cultural cleavages over immigration and European integration.5 As a member of the coalition government, the PvDA has acceded to a major austerity programme including cuts in provision for the elderly which has alienated its core supporters, having promised previously to return to traditional social democracy.6 In Germany, the SPD entered another ‘grand coalition’ with Merkel’s Christian Democrats in 2013; the dilemma for the SPD is how to differentiate its approach in a coalition, especially when the refugee crisis has antagonised its own working-class supporters. In fairness, according to the Economist “the SPD extracted some big concessions as a price for entering the coalition”, notably the minimum wage and capping rents in German cities.7 Nonetheless, the French Socialists and the German SPD have not succeeded in forging a shared approach to the eurozone crisis and austerity: in Germany, fiscal conservatism still prevails, even on the left, and the momentum for shifting the policy approach towards a ‘European growth compact’ has stalled.

Scandinavia has traditionally been the heartland of European social democracy, but even here, the omens for the centre left are hardly propitious. In Sweden, Stefan Löfven’s Social Democrats failed to secure an overall majority in national elections despite an unpopular centre-right government. The Social Democrats had already declined dramatically in the polls before the eruption of the refugee crisis; they came to power apparently lacking a political project for Sweden’s future. The consensus among Swedish voters in favour of immigration appears to be collapsing amid rising support in the polls for the Sweden Democrats.8 In the meantime, in Denmark the Social Democrats were ejected from government in 2015, despite becoming the largest party amid rising support for the populist right. The resignation of Helle Thorning-Schmidt as leader led to the installation of Mette Frederiksen who has vowed to continue with the policies of ‘economic responsibility’; she has signalled an intention to vigorously pursue the interests of ‘wage-earners’ while affirming the goal of full employment.9 The Social Democrats have also maintained a tough stance on the recent refugee crisis, refusing to be outflanked by the centre right on policy and rhetoric.10

Elsewhere in northern Europe, the British Labour party has suffered two consecutive general election defeats since 2010. The party recovered some support in 2015 achieving 30.4 per cent of the vote, but it won fewer seats due to the catastrophic meltdown of its electoral position in Scotland and its poor performance throughout much of England. Labour’s new leader, Jeremy Corbyn, hails from the far left and promises to rejuvenate the party by returning to traditional socialist principles; the polls so far indicate that he is struggling to convince a sceptical electorate despite the fact the governing Conservative party is badly divided over Europe. In Ireland, the Irish Labour party achieved its worst ever result in recent elections having been a junior coalition partner in a ‘pro-austerity’ coalition government; it won only seven parliamentary seats compared to 33 at the previous election. Nonetheless, there is speculation that the party might return to government, although many believe Labour must now go into opposition and rebuild its position from the backbenches.11

The socialist parties of southern Europe, notably Greece and Spain, have demonstrated growing strength since the 1980s, but they have been eclipsed since the financial crash. In Greece, the social democratic party, Pasok, sought to present itself as a force for national stability, but was catastrophically divided when the former prime minister, George Papandreou, formed a breakaway party, Kidiso (the Movement of Democrats and Socialists).12 This led to a splintering of votes on the centre left towards the radical alternative, Syriza; in the most recent Greek elections, Pasok achieved only 6.3 per cent of the popular vote. Syriza has moderated its position by doing what is necessary to keep Greece within the eurozone, further squeezing Pasok on the centre left. Syriza’s leader, Alexis Tsipras, has been able to execute this ‘U-turn’ since the majority of his voters want to moderate austerity, rather than leave the euro.13 This has left Pasok electorally and politically bereft. In Spain, Psoe achieved its worst ever result in the December 2015 elections, securing 90 parliamentary seats and 22 per cent of the vote. While Psoe was pivotal to the coalition negotiations, since a majority of votes went to parties of the left, the options did not appear palatable and there were fresh elections in June 2016. The PP secured 137 seats while Psoe managed to hold on to second place against a strong challenge from the left-populist party, Podemos, which secured 85 seats and 22.7 per cent of the vote.14 However, the problem for the Psoe is that any agreement with Podemos might rupture the Psoe’s own internal organisation, particularly over the issue of the future of Catalonia; a national unity government with Mariano Rajoy’s PP would be popular with the European Union and the financial sector, but it would simply reinforce the perception that the mainstream parties in Spain are ‘all the same’.15 The risk would be a further haemorrhage of votes away from Psoe. In Portugal meanwhile, the Social Democrats have entered a fragile coalition with other ‘leftist’ parties.

The exception to the rule of centre-left gloom in southern Europe is, of course, Italy. Matteo Renzi’s government has had some success in pursuing structural reforms to reduce taxes on employment and property boosting the private sector, aided by improvements in the performance of the Italian economy; according to the finance minister, Pier Carlo Padoan, “Italy is back”.16 The question for Renzi’s government is whether further progress can be made in reforming the Italian constitution and taking additional steps to prevent corruption; the prime minister faces a difficult referendum on constitutional reform later this year which he might well lose. Similarly, Malta has a successful centre-left administration in place.

The collapse of social democracy in eastern and central Europe since the 1990s has been remarkable. Astonishingly, Poland currently has no mainstream left parliamentary representation, as the Left Coalition failed to gain enough votes to beat the 8 per cent threshold, while the post-Communist SLD appear in danger of becoming obsolete.17 The Polish left has completely fragmented with an array of parties jostling for position and influence. The Czech Republic is currently governed by a social democratic prime minister, but elsewhere in the accession countries, Conservative parties prevail; even Hungary has shifted towards authoritarianism.18

Centre-left parties are not in government because they are losing elections; they are defeated predominantly because their electorates are fragmenting towards ‘challenger’ parties on the left and the right. The causes of defeat vary between countries: having decried capitalism since the financial crisis, social democratic parties seem more interested in debating problems than proposing concrete solutions; and on the major challenges of migration, security and terrorism confronting Europe, social democrats appear to have little new or important to say.19 Social democracy is not only electorally moribund; it lacks a ‘big idea’ for the future of European society. Against this backdrop, it seems plausible to predict the demise of the mainstream social democratic left in Europe. The chapter that follows will address which key voter groups the left is losing.

Notes

1. G. Moschonas, ‘Electoral Dynamics and Social Democratic Identity: Socialism and its changing constituencies in France, Great Britain, Sweden and Denmark’, What’s Left of the Left: Liberalism and Social Democracy in a Globalised World, A Working Conference, Centre for European Studies, Harvard University, May 9–10th, 2008.

2. https://medium.com/@chrishanretty/electorally-west-european-social-democrats-are-at-their-lowest-point-for-forty-years-ac7ae3d8ddb7#.degh68hxd

3. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-socialists-insight-idUSKBN0IG0H520141027

4. http://www.politico.eu/article/long-goodbye-of-the-european-left-francois-hollande/

5. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/07953.pdf

6. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4604

7. http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21601312-indulging-her-social-democratic-coalition-partners-angela-merkel-risks-turning-germany

8. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4973&title=The-summer-Sweden-became-obsessed-with-immigration

9. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4972&title=Frederiksens-balancing-act

10. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=5046&title=Denmarks-centre-left-is-in-disarray-over-the-refugee-crisis

11. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/reuters/article-3543275/Irelands-Labour-Party-considering-entering-government.html

12. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4834&title=Greeces-shifting-political-landscape.

13. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=4979&title=How-did-Syriza-manage-to-win-in-spite-of-its-U-turn

14. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/27/spanish-elections-mariano-rajoy-to-build-coalition-peoples-party

15. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=5049&title=Que-ser%C3%A1-ser%C3%A1-%E2%80%A6-whatever-will-be

16. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=5013&title=Italy-is-back-%E2%80%93-but-so-are-Renzis-PD-pains

17. http://www.policy-network.net/pno_detail.aspx?ID=5011&title=Where-now-for-the-Polish-left

18. http://www.politico.eu/article/long-goodbye-of-the-european-left-francois-hollande/

19. http://www.politico.eu/article/long-goodbye-of-the-european-left-francois-hollande/