Social democracy: a crisis of ideas?

The argument of this book is that the centre left is losing elections since it has patently lacked a distinctive, compelling project for the future. Social democrats have become increasingly defensive, both intellectually and politically, as they see the political landscape around them changing in ways that are hardly propitious for the left. In Europe and the United States, the rise of new populist forces on both left and right appears to be dragging politics in ever more radical directions, ‘hollowing out’ the political territory on which social democratic parties once stood. The rise of left and right populism has made the politics of western democracies more ‘noisy’, but this turmoil often disguises the fact that the majority of voters still yearn for competent, stable and broadly progressive government. In this environment, the centre left has to re-discover the courage of its convictions while setting out a new vision.

Social democracy and the third way

The debate about ideas on the centre left often begins with discussion of third way social democracy, the now infamous effort to modernise social democracy during the 1990s. An increasingly fashionable argument since the 1960s and 1970s has been that ideas no longer matter in politics: we have entered an age of technocracy and rationalism signalling ‘the end of ideology’. To some extent, this view underpinned the development of the third way. The third way’s core proposition was that ‘what matters is what works’; the practicality of policy and the results it generated mattered more than the ideological content of that policy. It was argued that social democrats had to break out of the conventional boundaries that traditionally separated left and right. Supporters of the third way insisted that this was a necessary act of ‘revisionism’, updating social democracy for changing times; but the third way’s opponents countered that centre-left parties were being shorn of their ideological convictions. This was more resonant in the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008–9, when centre-left parties were held to be culpable for inadequate regulatory oversight of financial markets while tolerating huge rises in economic inequality.

It is striking that in the late 1990s there was a wave of enthusiasm about the revival of progressive parties in US and European politics; however, this was accompanied by much debate, and perhaps even confusion, about whether electoral success would be translated into more profound social change (White, 1999). Rather than furthering progressive commitments to egalitarian reform, social justice, political freedom, and the extension of democratic governance, the perception was that many third way governments merely tinkered with an established Conservative settlement initiated by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the early 1980s (Gamble, 2010). In the US, Clinton’s New Democrats confounded the hopes of many progressive liberals by appearing to pander to a conservative agenda in order to secure re-election (Weir, 1999). In countries such as Britain and Germany, Tony Blair and Gerhard Schröder were regarded as the agents of a pro-market reform agenda under the guise of ‘modernising’ social democracy.

It can be legitimately argued that the core project of third way politics was a genuine response not only to the shattering of the post-1945 Keynesian settlement, but to structural changes that have occurred since the demise of the postwar social contract in the late 1970s. In the economy, dramatic changes were underway as a result of the internationalisation of capital markets and the expansion of world trade; the rise of information and communications technologies; the emergence of a ‘knowledge-driven economy’; and the shift from manufacturing to services that heralded a ‘post-industrial economy’ in the west (Callaghan, 2009). These economic forces interacted with important social changes, notably the fragmentation of traditional class structures; changes in the position of women reflected in growing labour force participation; demographic changes such as population ageing and the acceleration of labour migration; the apparent breakdown of traditional family structures; as well as an alarming decline of trust in democracy and government (Esping-Andersen, 2009).

In fact, many of the changes represented ‘opportunities’ as much as ‘threats’ for left parties; notably they instigated an unfinished feminisation process within social democracy which brought concerns about gender equality to the forefront of politics: there was no process of inexorable structural decline. The prediction that social democratic parties were doomed to defeat because of changes in the class structure proved to be exaggerated. Nonetheless, such developments made it harder to build a stable, cross-class alliance to match the power of organised labour in the 1950s and 1960s, the halcyon days of the postwar welfare state (Cronin, Ross & Schoch, 2010). The constraints imposed by globalisation, increasing welfare dependency, and declining faith in government appeared to circumscribe what social democratic parties were able to achieve in office. Indeed, the shift towards more dynamic and volatile ‘issues-based’ politics combined with the growing importance of perceived governmental competence and performance have created a febrile environment for governing parties of all ideological complexions (Stoker, 2006).

The third way was a concerted attempt to rethink social democratic politics in the wake of the Thatcher-Reagan hegemony, alongside the apparent dominance of ‘neoliberal’ ideas in advanced capitalist democracies. Numerous critics have sought to subject the third way to extensive critique since the mid-1990s. For instance, academics such as Chris Pierson (2001) insist that the third way had overstated the impact of economic and social change especially that associated with globalisation. In a similar vein, Ashley Lavelle (2008) argues that the third way entailed an unnecessary degree of accommodation with neoliberalism. The terrain of a distinctive left political economy centred on market intervention was prematurely abandoned. Marcus Ryner (2010), benefiting from the hindsight afforded by the 2008–9 financial crash, avers that New Labour’s model of social democracy meant a ‘Faustian’ bargain with market liberalism. The legacy was growing income inequality and an economy dangerously unbalanced by financialisation. Finally, the Swedish political scientist Jenny Andersson (2009) observes that third way social democracy entailed an emphasis on the rise of the ‘knowledge-driven economy’, which justified a new compromise between the private sector, workers and the state unified by the goal of widening access to human capital. Andersson concludes that the third way assimilates all forms of human potential and the public good under the rubric of economic growth and higher productivity, aiding the remorseless process of commodification in capitalist societies.

Other important structural changes in the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ economies were also downplayed or ignored by the third way. These included the substantial increase in earnings and income inequality in many western countries; the growing concentration of wealth among the richest one per cent of the population; the growth of relative poverty (especially child poverty); persistently high rates of economic inactivity among the unskilled (especially in the UK and some continental European states); as well as the emergence of excluded minorities economically and geographically isolated from the economic and social mainstream. The third way confronted a core paradox: economic and social change was generating new demands for progressive intervention by the state; at the same time, these very forces were eroding and undermining citizen’s trust in government, which manifested itself in declining election turnouts and growing disillusionment with the political process. Social democracy struggled to reconcile its aspirational rhetoric centred on social justice and the equal worth of all with the economic and political realities imposed by governing a liberal capitalist economy.

Moreover, the third way implicitly assumed that social democratic parties would converge around a single model of centre-left governance; but there have always been strikingly divergent national pathways within social democracy: there are distinctive models of British, French, German and Nordic centre-left politics. More recently, the British model has accepted globalisation and flexibility in capital and labour markets tempered by ameliorative government intervention. The German centre left has undertaken liberalising reforms since the late 1990s, but preserved the corporatist model of tripartite cooperation between employers, trade unions and the state. Similarly, the Nordic social democratic parties have remained open to globalisation and free trade, but have embedded the traditional pillars of the Scandinavian model such as collective wage bargaining and a relatively high density of trade union membership. Finally, the socialists in France have accepted some reforms of the state’s role in the economy, but the French left remains committed to achieving a high level of social protection through government regulation and intervention. This point underlines that there have always been ‘multiple third ways’ for social democracy in Europe.

Neither are the various criticisms of the third way always convincing: for example, Ben Clift and Jim Tomlinson (2007) have taken issue with the claim that UK centre-left modernisation in the late 1990s meant the abandonment of postwar Keynesian social democracy. For one, previous British social democratic governments in the 1940s and the 1960s had never been avowedly Keynesian: they were committed to nationalisation, more interested in economic planning, and rather distrustful of Keynesian theories which sought to defend the legitimacy of the liberal market economy. New Labour did not abandon demand-management but combined it with supply-side policies; the pursuit of ‘credibility’ was intended to create more space for fiscal activism as public spending grew markedly as a share of GDP after 1998–9; indeed, the Blair-Brown governments were fundamentally committed to the quintessentially Keynesian goal of full employment (Clift & Tomlinson, 2007: 66–69).

Moreover, for all the intellectual critiques of the third way, the prolonged attempt to ‘modernise’ social democracy was a serious effort to rejuvenate centre-left ideas. The economic crisis and the imposition of austerity in the wake of the great recession have underlined that ideas matter in politics. Ideas create ‘cognitive frameworks’ which are the precondition for political and policy action, as Mark Blyth (2011) has pointed out. It is ideas that enable social democratic parties to forge new coalitions for change, breaking down the influence of vested interests. As John Maynard Keynes famously remarked, ‘The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else’.1

In revising the third way since the 1990s, social democrats in Europe have developed three distinctive frameworks of ideas that are briefly reviewed in the chapter below: first, the turn towards ‘communitarianism’ associated with Blue Labour in Britain; second, the reassertion of a nascent version of cosmopolitan liberalism; and finally, the call for a renewed attack on economic inequality on the left.

The Communitarian Turn: ‘Making Sense of Blue Labour’

Communitarianism is a plural political ideology with roots both on left and right. The set of ideas known as Blue Labour have dominated internal debate within the British Labour party since its devastating 2010 defeat, among the worst the party has suffered since 1918. Similarly, in the Netherlands and Germany there has been a growing interest in communitarian ideas among social democrats, partly in reaction to heightened concerns about the long-term impact of migration on solidarity and community.

Election defeats have triggered an inevitable period of soul-searching, the most tangible product of which has been the Blue Labour prospectus. This occurred in the absence of any serious intellectual contribution either from the organised left or the remnants of New Labour. Exponents of Blue Labour expressed their ideas in the language of ‘love, community, neighbourliness, fraternity, relationships and the common good’. This was unusual in British politics, while leading Blue Labour exponents made a series of controversial claims. Maurice Glasman, widely viewed as Blue Labour’s leading intellectual voice, argued that the Labour governments had been dishonest about their intensions in liberalising immigration policy and accepting free movement of labour, as they feared a backlash from voters. Glasman was appointed to the House of Lords in 2011 by Ed Miliband, then Labour leader; his views have been taken seriously by the British media and the political class.

Blue Labour did not just provide a critique of immigration policy, but entailed a commitment to reclaiming past traditions, including respect for working-class life and the values of solidarity and collectivism that once animated the British left. The prefix ‘blue’ indicates a residual sympathy towards conservatism as a philosophy, not to be confused with the British Conservative party, which remains avowedly free market; it speaks to an appetite in the country to protect, safeguard, and improve the vital aspects of our common life, in particular England’s language, culture and institutions (Rutherford, 2010). Blue Labour embodies several important strands in the Labour tradition. It is a complex amalgam of distinctive ideological and intellectual tendencies which shares certain similarities with earlier phases of Labour party thought, namely the ethical socialism of Ramsay MacDonald and RH Tawney; the commitment of Clement Attlee’s Labour to a democratic ‘common culture’ in the postwar years; the pragmatic labourism of Harold Wilson and James Callaghan in the 1960s and 1970s; alongside the distinctive communitarianism and ethical socialism of the Blair years prior to 1997 (Rutherford, 2010).

Blue Labour involves an array of diverse and distinct positions. For example, Glasman is a strong exponent of the politics of virtue and the common good rooted in the social teaching of faith communities. Others emphasise the importance of Labour rediscovering its commitment to a democratic ‘common life’. The cultural theorist Jonathan Rutherford (2010) draws attention to the importance of rooting politics in everyday lived experience, particularly the parochialism of England, English culture and English identity. However, what unifies Blue Labour is its resistance to the commodification of human beings through markets, which allegedly strips life of all that is intrinsically valuable, echoing the early writings of Karl Marx and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Their most inspirational theorist is Karl Polanyi who has shaped the thinking of Glasman in particular, by examining the impact of capitalist markets on 17th and 18th century England. The process of commodification has been intensified in the 21st century by New Labour’s commitment to a ‘dynamic knowledge-based economy’ driven by globalisation. Unlike other anti-capitalist movements, Blue Labour sees capitalism as a problem not of class exploitation or structural inequality, but primarily of commodification and the unruly forces of capital (Glasman, 2010). The aim of left politics ought to be to resist the forces of marketisation that transform individual citizens into commodities.

In policy terms, Blue Labour embraces ‘stakeholder’ economics, redirecting British capitalism from its Anglo-American orientation towards northern European models centred on German and Scandinavian experience. In practice, that means a commitment to corporatism involving workplace partnership between employers and the workforce; altering the culture of mergers and takeovers; restraining executive remuneration; as well as curtailing the ‘hire and fire’ culture of the American labour market. It entails much greater emphasis on vocational skills and training, celebrating the permanence of ‘craft and vocation’ rather than endlessly flexible human capital. Another aspect of its economic model is the localisation of political authority and power through city government, alongside the regionalisation of the banking system.

Most European social democrats would regard this as a mainstream centre-left programme. Blue Labour has been a constructive exercise in mapping out and framing a distinctive social democratic project in the wake of the global financial crisis. Nonetheless, the overall coherence of Blue Labour remains doubtful. The most important weaknesses relate to class identity; the risk of parochialism; and the absence of a plausible account of political agency.

Blue Labour exponents have been right to draw attention to the continuing relevance of class as a marker of economic and political identity. New Labour may have gone too far in abandoning the party’s historic role as an agent of working-class solidarity and collective organisation. Nonetheless, it can hardly be doubted that class has ceased to play the role that it once did in British political life, and Labour’s response to this was a necessary precondition for electoral recovery in the 1990s. In the first half of the 20th century, individuals (predominantly men) understood their position in terms of their status as producers and workers. Today, the role of ‘consumers’ is a far more prevalent aspect of social and political identity; centre-left politics has had to come to terms with the rise of the consumer society (Callaghan, 2009). The left might decry these historical developments, but the failure to comprehend the rise of affluence and consumerism has been politically costly. Even more to the point, the manual working class has shrunk dramatically in size across almost all advanced economies, and is no longer in a position to propel social democratic parties to victory.

A further vulnerability within Blue Labour’s ideology is that of parochialism (Runciman, 2013). The desire to re-galvanise local places and the spirit of community is legitimate, but the reality of global interdependence is hard to refute given the growing importance of globalised production chains. Liberal cosmopolitanism may have its weaknesses, not least alienating those who have failed to gain from the globalisation of economic production, but ‘socialism in one country’ has scarcely appeared credible since the 1960s and 1970s. Any social democratic government is constrained by international markets alongside dependency on overseas investors and foreign capital. It is far from obvious that international market forces can be resisted by exerting the nation state’s power as a sovereign actor. What is lacking from Blue Labour is an account of political agency, of how desired changes are to be brought about given the obstacles imposed by existing political and economic realities. The risk for its exponents is of falling into a traditional void: failing to reconcile a radical form of rhetoric with the practical means to fulfil Blue Labour’s vision of a fairer, more equal society.

Liberalism and social democracy

If Blue Labour and social conservatism is not wholly the answer, should the left reclaim the social liberal tradition? In particular, the American political tradition centred on faith in progressive liberalism has long provided social democrats in Europe with ideas and ideological inspiration. This extends from Theodore Roosevelt’s progressive reform movement at the turn of the 20th century, to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s, through to Lyndon Johnson’s 1960s Great Society, and the ‘New Democrat’ fusion of fiscal responsibility and social liberalism under Bill Clinton in the 1990s. At the core of that tradition is a belief in an ethic of liberalism underpinned by the notion of ‘positive freedom’: the idea that citizens will fulfil themselves not merely by achieving liberty from external constraint, but by having the power and resources to fulfil their full potential. Positive liberty is enhanced by the ability of citizens to participate in their government and civil society, and to have their voice, interests and concerns recognised as valid and acted upon (White, 1999). This is at the root of the enduring vision of economic and social progress provided by progressive liberalism in the US.

The relationship between liberalism and social democracy has long been contested, particularly among parties of the left who sought to differentiate European socialism from American liberalism (Sassoon, 1996). Nonetheless, notions of civil rights, democratic accountability, personal liberty, and civic duty have remained influential. Throughout history, socialists and social democrats have sought to temper their faith in the power of government by recognising the importance of protecting citizens from overweening concentrations of power, investing in institutions and policies that would enable citizens to flourish regardless of background or birth. At root, social democratic and socialist parties in western Europe have long drawn strength from their immersion in liberal traditions and ideological lineages (Freeden, 1978).

Today, the contribution of progressive liberalism to the contemporary political debate appears questionable. On both sides of the Atlantic, centre-left parties are struggling to establish a clear ideological direction in the wake of the financial crisis. Since the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, social democrats in the European Union have lost 26 out of 33 national elections. In Britain, Germany and Sweden, the left has experienced among the worst defeats in its history. The challenge for those of a progressive temperament is to come to terms with the collapse of faith both in markets and the state in the wake of the financial crisis. The death of neoliberalism has been widely proclaimed2, but few varieties or models of capitalism have appeared to fill the void created by the collapse of confidence in financialised capitalism.

The crisis has evolved from a crisis of global financial markets, to a crisis in the international banking system, to a crisis of sovereign debt, to a wider crisis of declining trust in governments and the democratic system (Gamble, 2012). This alludes to a deep crisis of legitimacy and trust in liberal democracy in the advanced industrialised nations. In domestic politics, at exactly the moment when stagnating economic growth is squeezing living standards and the revenues available for public investment, faith in the democratic institutions that are intended to ensure a fair distribution of the burdens of austerity is receding. Citizens are equally perplexed by the consequences of globalisation: on the one hand, they want to be protected from the myriad insecurities unleashed by the free movement of goods, services and finance. On the other hand, they seek greater choice and control over their lives, and remain suspicious of an overmighty, centralising state (Mulgan, 2005). It is no surprise that questions of identity, nationhood and belonging have returned to the fore of contemporary politics.

This is the context in which 21st century progressive movements have to rediscover their political vitality and sense of ideological purpose. This book considers whether re-engagement between the American and European progressive traditions can help to forge new doctrines, narratives, and strategies that have the potential to inaugurate a paradigm shift beyond neoliberalism in the advanced democracies, while providing the resources through which to affect a broader recovery in the fortunes of social democratic politics.

Social liberalism and the future

It might be argued that social liberalism is therefore of little relevance to the contemporary political context given its embrace of free markets and complacency about rising inequalities. Social liberalism merely replicates the weaknesses of the third way approaches already alluded to. Critics have suggested that social liberalism has repeatedly ignored or understated the potential for state intervention and non-market coordination. Social liberalism is portrayed as concerned with ensuring that citizens have roughly equal starting points, but then allowing the market to run its course (White, 1999). It is argued that there is little to distinguish social liberalism from neoliberalism. The third way version of social liberalism was said to have been oblivious to the range of institutional legacies that different progressive and social democratic parties have faced, and the extent to which they have been able to draw upon, and develop, social liberal ideas in power (Weir, 1999). Nonetheless, while it might appear that social liberalism has little to offer social democracy in the wake of the economic crash – a crisis which the left believed might allow the return of the centralised state to the centre of policy debate – that conclusion has turned out to be misplaced. For instance:

• Social liberals have always stressed the potential for market failure, privileging neither the state nor market instruments; they argue for the pragmatic integration of state and non-state actors in the economy, including the strengthening of the mutual and not-for-profit sector (White, 1999).

• Progressive liberals have long acknowledged that they have no alternative but to periodically revise their programmes in the light of the changing nature of capitalism. They have also accepted the need to face up to the dilemmas implicit in the trade-off between economic efficiency and social justice (Meade, 1993).

• Social liberals have affirmed a major role for the state both in tempering the earnings inequalities that labour markets create through the minimum wage and skills policies; and by developing programmes through which risks can be pooled in order to meet responsibilities such as caring, as well as life course needs (Esping-Andersen, 1999).

• Social liberalism seeks to alter the distribution of assets that citizens bring to the market through ‘social investment’ strategies (Jenson & Saint-Martin, 2003). Social liberalism is perfectly compatible with a conception of ‘strong egalitarianism’. The problem since the late 1990s was that many third way governments lacked strategies that would end the entrapment of low-waged workers in poor quality jobs, or that challenged the low-wage, low-productivity ‘disequilibrium’ in Anglo-Saxon economies.

• A number of liberal economists and political theorists have explored the potential for ‘asset-based egalitarianism’ to improve the equity/efficiency trade-off in market economies. Such proposals have included universal capital endowments financed through inheritance tax, and a citizen’s income funded through public investment in capital markets (White, 1999).

• A liberal public philosophy remains important for negotiating contemporary policy dilemmas, not least democratic governance reform, anxieties about immigration management, civil liberties, community cohesion, and issues relating to the rights and duties of citizens (Weir, 1999). A central thrust as Margaret Weir argues is that means must be found to encourage citizens to engage and participate in the political process. The debate between ‘liberal’ and ‘communitarian’ conceptions of civic responsibility can help to clarify the underlying purpose of progressive policy initiatives.

Progressive left parties ought to consider how to unlock new ‘political opportunity structures’ given the growing fragmentation and fluidity of politics (Cronin, Ross & Schoch, 2010). Reconsidering the relationship between social liberalism and social democracy ought to be integral to that process. What is required is a vigorous development of the ‘new’ liberalism that emerged at the turn of the 20th century, with its roots in a broader tradition of democratic and social republicanism stretching back to figures such as LT Hobhouse, TH Green and Thomas Paine (Freeden, 1978). This is a reminder that liberalism was once a popular movement anchored in working-class institutions across civil society – the trade unions, friendly societies, worker’s education, and the chapel. It is worrying that over time, the civic institutions of progressivism have been allowed to atrophy and decline (Rutherford, 2014). The task today is less about inventing an entirely novel approach to ‘liberal’ social democracy. Instead we ought to be concerned with drawing on, and re-appropriating, these rich traditions and narratives in order to engage more forcefully with the challenges of the present (Gamble, 2010).

Inequality

In contradistinction to reclaiming a lost social liberalism, others on the left advocate a renewed offensive against inequality. It is claimed the fight against inequality ought to be the lodestar of the left, but we need to be clear both about what causes inequality, and more importantly, what constitutes social justice and equality today. For generations, political theorists have struggled to formulate a convincing conception of the egalitarian ideal.

In the debate about what creates economic inequality, a host of factors have been cited in a burgeoning literature (Taylor-Gooby, 2013). Rising immigration is one driver. Declining rates of unionisation is another. Both are believed to have weakened the bargaining power of low-skilled workers, alongside the fall in the relative value of the national minimum wage in many countries. Another factor is the growth of international trade and the globalisation of labour, product and capital markets since the 1980s: as the balance of economic advantage shifts to the east, many jobs in the west become uncompetitive or obsolete. Each of these explanations has received considerable attention from politicians and policymakers. This is hardly surprising since there is evidence that these factors have each contributed to the sharp rise in inequality of income and wages, especially in the US and the UK.

According to research presented by Alan Krueger, one of US president Barack Obama’s economic advisers, the most important driver of economic inequality is ‘skill-biased’ technological change, as Figure 4.1 makes clear. This increases the number of relatively skilled jobs at the top of the labour market, while skewing the wage distribution towards those with the highest levels of human capital (Goos & Manning, 2014). There is considerable debate within the economics profession about the impact of technological change, but it is unquestionably a potent driver of inequality mediated by education and skills. The OECD has recently predicted that jobs requiring ‘highly educated workers’ will rise by 20 per cent in the next decade across the advanced economies, whereas low-skilled jobs are likely to fall by more than 10 per cent.

Moreover, low-skilled workers are increasingly vulnerable to the threat of redundancy and unemployment in a period of ongoing economic restructuring. In the EU28 countries, 84 per cent of working-age adults with ‘higher’ (tertiary level) skills are currently working compared to less than half of those with low skills (Sage et al, 2015). Downward pressure on wages and fear of unemployment is leading to heightened economic insecurity for those on lower and middle incomes. Across the OECD, median income households have experienced a much sharper decline in incomes than was the case 30 years ago.

Figure 4.1 Causes of Earnings Inequality. Source: Economic Report of the President, 1997

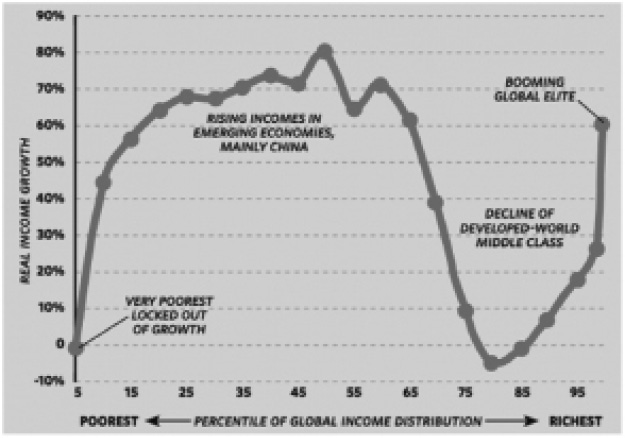

Figure 4.2 Global Income Growth, 1988–2008. Source: The American Prospect, using data provided by Branko Milanovic3

Figure 4.3 Income Inequality: Gini Coefficient. Source: EU Community Statistics on Income and Living Conditions; the data is for 2009; updated December 2010

The whole of Europe has clearly been afflicted in recent decades by rising inequalities. But work by Branko Milanović which produced the famously termed ‘elephant curve’ demonstrates more precisely who has gained and who has lost out across the income distribution in the global economy, as shown in Figure 4.2. In summary, the poor in developing countries who three decades ago lived in abject poverty have gained significantly from global economic integration. The ‘losers’ have been middle-class groups in already rich countries who have lost out in the income distribution compared to the wealthy minority: Milanović’s argument is that the forces driving inequality in both industrialised and developing states are resolutely global, yet the policy response to inequality remains predominantly national.4 This should serve as a warning to those who believe that Britain’s withdrawal from the EU is likely to produce gains in income and wealth equality over the coming decades. Meanwhile, Figure 4.3 illustrates the prevalence of inequality across the EU as measured by the Gini co-efficient.

As Milanović’s work underlines, structural trends in the global economy have led to substantive inequalities in the wage and income distribution in rich market democracies, attenuated by the crisis of 2008–9. At the same time, governments have been less effective at mitigating the risks increasingly associated with global economic integration and openness to the world economy. A paper published by the economist Dani Rodrik in the late 1990s illustrates the point: at the beginning of the 1990s Rodrik (1998: 997) found that in countries that were more exposed to global trade such as Norway, Sweden and Austria, the size of government expenditure was greater. His explanation: public spending is used to insure citizens against increasing external risk; in the advanced capitalist countries, government expenditure on welfare and social security protects individuals against volatility in employment, incomes and consumption. From this, we can see how two particular problems have arisen in EU member states since the financial crisis. First, the union was predicated on a ‘division of labour’ in which the EU is a force for liberalisation through the single market, while it is nation states that protect citizens from external risk given the underdeveloped social dimension of Europe. The increasing inability of national governments to perform this role given escalating public sector deficits since 2008 has imperilled the EU as a political project. Second, the inability of governments to constrain the impact of global economic integration through ‘risk-mitigating’ expenditures illustrates the growing structural divergence between politics and markets. The historical role of social democracy was to better reconcile markets with politics to reduce class conflict and to foster democratic stability: it is little wonder that centre-left parties are increasingly on the back-foot.

Moreover, governments at all levels have struggled to live up to the challenge of equipping individuals to face new uncertainties in their working lives, coping with risks such as obsolete skills and inadequate education. Nearly one in seven (around 78 million people in Europe) are at risk of poverty; shockingly, child poverty has continued to rise across member states over the last decade (Esping-Andersen, 2009). Children (0–17) have a particularly high rate of poverty at 19 per cent. One-parent households and those with dependent children have the highest poverty risk; for single parents with one dependent child, the risk is currently 33 per cent; other age groups at a high risk of poverty are young people (18–24) at 18 per cent, and older people (65+) at 19 per cent; older women are at a considerably higher risk than men (21 per cent compared to 16 per cent) (Sage et al, 2015). As highlighted earlier, these figures do not include some of those in the most extreme situations, particularly ethnic minority groups. Of course, poverty rates are notably only one dimension of social injustice, and inequality.

Welfare states have arguably placed too much emphasis on passive income redistribution and ‘insider’ guarantees of social protection, without helping to equip Europe’s citizens for the competitive challenges of the future. The more recent labour market research demonstrates that wage inequality in Europe has intensified since the late 1990s: while income redistribution has been strengthened, labour market regulation and wage protection have eased (Goos & Manning, 2014). This has, in turn, fuelled the legitimacy crisis facing the EU, which is increasingly blamed for the negative consequences of globalisation, liberalisation and austerity.

The main drivers of growing inequality inevitably vary across the Europe continent. In the core continental member states, slow growth and rising unemployment have been a particular challenge for the last three decades. For the 10 member states that joined the EU in 2004, including the eight former communist countries, this has been a fraught period of transition and adjustment; for the ‘periphery’ countries, namely Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Spain, there has been a phase of rapid modernisation, at least until the financial collapse of 2008–9 (Sage et al, 2015). In contrast, the Nordic countries have developed social models that led to outstanding growth performance since the early 1990s.5 It might be expected that these factors are reflected in public attitudes to the varying dimensions of social justice.

At the same time, while there is great diversity between, as well as within, countries, all member states face common challenges such as demography, increased ethnic and cultural diversity, and the individualisation of values (Lerais & Liddle, 2006). Every member state in the EU is a relatively open society shaped by the forces of international capital, alongside global cultural trends and values. In many societies, there is an increasing cultural gap between ‘cosmopolitans’ who are portrayed as the ‘winners’ of globalisation and social change, and those who are left behind through the economic transition, perceiving their traditional values, neighbourhoods and sense of belonging to be under threat (Callaghan, 2009). This new divide between ‘liberals’ and ‘communitarians’ forms an important backdrop to public attitudes in relation to social justice.

Crisis Aftershocks AND THE NEW INEQUALITIES

Social democrats also need to understand how the world is changing to increase inequality and polarisation: ‘crisis aftershocks’ since 2008 have made it tougher to carry out social democratic programmes in pursuit of equality and social justice across Europe. First, current crisis aftershocks originate in long-term structural trends relating to demography, life expectancy, globalisation, and the changing shape of the productive economy in the west, not just the financial crash itself (Sapir, 2014). These trends are common across the EU’s member states, despite their different stages of economic development. In some respects they have been exacerbated by the global shocks of 2008–09 as Andre Sapir has argued, which has underlined the global shift in economic power away from Europe and the rest of the developed world, as shown by the remarkable resilience of the emerging Asian economies. By contrast, the consequences of the shock to growth and the public spending consequences of the financial crisis will make it harder to address long-term social and economic challenges. Many European governments struggled to implement immediate crisis management measures, and have had to deal with the fallout of the sovereign debt crisis. In the meantime, hastily conceived fiscal austerity measures have had a major impact. The danger is that during an era of fiscal retrenchment, existing welfare policy regimes will be frozen as governments struggle to reassure citizens and protect people from the adverse consequences of the crisis. It is precisely at this moment, however, that reform is needed most, not only to manage new financial pressures, but to make welfare states more resilient for the future and prevent the crisis from further damaging the life chances of the least advantaged in society.

These crisis aftershocks have nonetheless put social and economic inequality back at the centre of the public policy agenda. In a recent book, The Spirit Level, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett show that unequal societies do far worse on a range of important social indicators including crime rates, public health, educational achievement, work-life balance, personal wellbeing, and so on. Thomas Picketty’s work has demonstrated that the rate of return on capital exceeds the growth in wages in capitalist economies, leading to a long-term rise of inequality. Of course, the inequality debate has become broader than the traditional focus on economic inequality and the relationship between the top and bottom of the distribution. A new focus relates to the stagnation of the ‘squeezed middle’ and the downward pressure on their living standards created both by globalisation, and internally driven pressures such as deregulatory labour market reforms undertaken with the objective of raising employment participation rates (Sapir, 2014). The question of inequality cannot be separated from the wider debate about the nature of capitalism in the west, which has led to the revival of interest in the German coordinated social market economy regime, and the successes of globally orientated Nordic social democracy in combining efficiency and equity.

The final argument concerns the capacity of the European Union to present itself as a strategic actor well-placed to deal with the fallout of crisis aftershocks, helping to facilitate the return of Europe’s economy and welfare regimes to stability and good health. This optimistic view of the EU’s potential underestimates the extent to which the EU itself has accentuated the scale of the social inequalities facing member states principally through the dynamics of the internal market (Sage et al, 2015). Combined with EU enlargement, the single market has contributed to the increasingly adverse fortunes of the low skilled in the labour market and the erosion of labour standards. There is also the issue of whether the established EU policy framework, with its emphasis on fiscal discipline, national competitiveness and labour market reforms has contributed to the rise of zero-sum competition between member states (Sapir, 2014). Whereas before the crisis social policy experts imagined that membership of the EU contributed to a positive ‘race to the top’ for its national welfare states, the real impact of the crisis has been to exacerbate economic and social divergence in Europe, as member states find themselves with widely differing room for manoeuvre and therefore seeking different remedies to the challenges presented by the crisis (Sage et al, 2015). The ethic of solidarity between EU countries is weakened as a result. The basic legitimacy of the EU is put into question. Maurizio Ferrera has examined how national welfare states within the EU operate both within a clearly defined ‘European economic space’ as well as a more imprecise ‘European social space’, the parameters of which could now be altered, not least as the application of the new social provisions of the Lisbon treaty unfolds.

As a result of these changes, a growing ‘social justice deficit’ exists across Europe:

• Full employment no longer exists in most member states. In France, unemployment has hovered around 10 per cent for the best part of two decades with over a quarter of young people unable to find jobs. Even high-employment countries like the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK continue to have serious problems of working-age inactivity, in particular the number of claimants for sickness and invalidity benefits (Lerais & Liddle, 2006).

• Security against social risks is now partial. Welfare systems insured more or less successfully against the risks of 19th century industrialisation (unemployment, sickness, industrial injury and poverty in old age) with some gaps in countries which saw the family as taking full responsibility for young people for example. But European welfare states have found it more difficult to insure against the new social risks of modern life (single parenthood, relationship breakdown, mental illness, extreme frailty and incapacity in old age).

• Fairness between the generations has broken down. Pensioners have done relatively well, and the problem of poverty in old age is more confined to the new member states. However, child poverty is a major issue in several European countries. In others young people bear the brunt of unemployment and fiscal retrenchment.

• The quality of public services in many continental countries is beginning to decline after years of public spending restraint created by slower growth. Many member states have an endowment of high-quality infrastructure built in a more economically dynamic era, but this will increasingly fray at the edges if growth remains slow and public finances tight.

• The industrial relations system that was supposed to guarantee fair treatment at work no longer protects the ‘weak’ against the ‘powerful’. Some groups are well-protected as a result of social partnership, strong trade unions, collective agreements and legally enforceable employee rights, but they are privileged because they do not represent the majority of the workforce and those excluded from it. There is an increasing ‘insider’/‘outsider’ division in European labour markets (Sapir, 2014).

• Most Europeans favour a society that leans against inequalities, although political parties differ about the degree of inequality they find tolerable. Inequalities are, in fact, growing in most member states as the result of higher rewards at the top as well as greater employment inactivity and low wages at the bottom. Inequalities in income and wealth are politically contested. However, the commonly-held aspiration that ‘every child should have an equal chance in life’ is less in reach than a generation ago; the disadvantages of social inheritance are becoming more embedded (Esping-Andersen, 1999; Sage et al, 2015).

Neither ‘pure’ equality of outcome nor ‘radical’ meritocracy

Social justice and equality have been the animating ideals of European social democracy for much of the last century. They reflect the core commitment of the centre left to substantive freedom, not only access to basic liberties and the right to self-determination, but the ability to exercise individual autonomy through the opportunity and security afforded by an active and enabling state. The role of government is not to act as a barrier to freedom, but to enable and enrich personal liberty. Nonetheless, despite their evident political resonance in social democratic parties, social justice and equality are ambiguous and contested concepts, with varying degrees of purchase both within and between European societies. Equality in particular has been attacked as representing ‘levelling down’ through indiscriminate redistribution and punitive rates of income tax. For that reason, many social democrats have preferred to highlight their commitment to ‘social justice’; the political theorist David Miller has identified four pre-eminent dimensions of social justice:6

• Equal citizenship: every citizen is entitled to civil, political and social rights including the means to exercise those rights effectively.

• The social minimum: all citizens must have access to resources that adequately meet their essential needs, and allow them to live a secure and dignified life in today’s society.

• Equality of opportunity: an individual’s life chances, especially their access to jobs and educational opportunities, should depend on their own motivation and aptitudes, not on irrelevant markers of difference such as gender, class or ethnicity.

• Fair distribution: resources that do not form part of equal citizenship or the social minimum may be distributed unequally, but the distribution must reflect ‘legitimate criteria’ such as personal desert, effort and genuine risk-taking rather than gaming economic rents through monopolistic markets (Miller, 1994: 31–36).

Miller’s aim was to identify the core principles citizens use to judge whether their societies are just or unjust. Of course, it might be argued that Miller’s list is deficient or at least inadequate. The principle of equality of opportunity does not explicitly take account of increasingly important intergenerational inequalities, particularly in the light of climate change and its impact on future generations, as well as de facto redistribution towards older citizens and retirees. At the same time, Miller’s conception of social justice is framed in terms of rights and entitlements; he has relatively little to say about reciprocity and civic responsibility, the mutual obligations and duties that bind together political communities. Another gap in Miller’s account relates to power: any persuasive account of social justice should capture the importance of giving individuals the power to shape their own lives, rather than being held back by the destiny of circumstances or birth.

Miller’s framework undoubtedly offers an engaging and fruitful starting point for debate about the core purpose of social democracy. However, developing abstract understandings of social justice is plainly inadequate. As Peter Taylor-Gooby (2012) has indicated, it is necessary to understand the complexity of public attitudes, how public policy can work with the grain of public views, and where political parties might need to challenge the attitudes of voters. The evidence suggests that the public do not conceive social justice in terms of grand theories, but tend to relate conceptions of justice to specific life events, contexts and particularities (Mulgan, 2005). This is an important reminder to politicians; to capture the public’s imagination they must relate their values to specific and tangible policy goals, rather than to intangible theoretical principles. The role of political theory is to help frame the narrative and discourse of social justice on which politicians can subsequently draw.

Attitudes do matter, not least because the literature indicates that how the public perceives inequality, poverty and the income distribution are an important aspect of a country’s ‘welfare culture’ (Lepianka, Van Oorschot & Gelissen, 2009). These perceptions shape both the perceived legitimacy of particular welfare programmes, but also the overall shape and design of the welfare state. An important distinction is emphasised between those countries where poverty tends to be blamed on the ‘irresponsible’ behaviour of the poor (notably the United States), and those states where ‘structural explanations’ are emphasised in interpreting the prevalence of poverty (particularly the Continental and Nordic countries in Europe) (Lepianka, Van Oorschot & Gelissen, 2009). The point to emphasise is that underlying public attitudes have implications for the viability and legitimacy of social policy programmes, as well as for the capacity of European social democratic parties to frame their agendas in terms of enduring social justice principles (Taylor-Gooby, 2012).

Attitudes are of course inherently complex: for example, findings from the most recent UK social attitudes survey show that public attitudes towards poverty and the poorest in society have hardened since the 1980s, despite the election of a Labour government committed to eradicating poverty. For example, in 1989, 51 per cent backed policies to redistribute income from rich to poor, but this had fallen to 36 per cent by 2015, although 78 per cent remain concerned about the extent of wealth inequality in the UK (Sage et al, 2015). Some commentators argue that the decline in support for policies to tackle poverty reflects the unwillingness of leading social democratic politicians in Britain to talk more explicitly about the case for redistribution and a comprehensive welfare state. However, political scientists have questioned this by proposing a so-called ‘thermometer effect’: voters will support a party which promises to correct current problems such as rising inequality, but once the party has entered power and enacted those policies, support for redistribution and higher taxes will inevitably decline.

Nonetheless, it is important to emphasise that while public perception helps to shape policymaking, governments have the power to influence perceptions in order to enhance the legitimacy of their policies. Political parties are not the passive beneficiaries of underlying shifts in public opinion, but rather have the capacity to frame and shape the attitudes and perceptions of voters. The centre ground of politics is not given, but can be contested and reshaped on the basis of a sharply defined ideological and programmatic appeal. Parties should actively seek to alter the public mood, rather than being imprisoned by a particular instinct as to what voters will, or will not, accept (Taylor-Gooby, 2013).

This concern with public attitudes has focused increasing attention on the processes of ‘perception formation’ among citizens, notably through the media. At the same time, it is important not to underestimate the importance of wider social influences and networks in shaping attitudes and values, as well as the role of ideas in framing public agendas. It is wrong to suppose that interests matter more than ideas, “since the interests which individuals pursue have to be articulated as ideas before they can be pursued as interests” (Gamble, 2009: 142). Ideas are more often weapons in the struggle to define the dominant discourse and conception of political ‘common sense’, shifting the axis of politics irreversibly in a social democratic direction. Unquestionably, ideas matter; there will be no revival of centre-left politics in Europe without a thoroughgoing and fundamental renewal of ideas.

Public attitudes To social justice

How European social democratic parties and governments frame their appeal to social justice has major implications for their electoral salience and governing success. The various dimensions of social justice, to a greater or lesser extent, reflect intuitive understandings of fairness and desert, as such they help to ground centre-left politics in a broader conception of the common good. There are discernibly three key challenges ahead in developing the politics of social justice (Taylor-Gooby, 2013).

The first challenge concerns the importance of building ‘reciprocity’ in the welfare system. There is concern about the extent of income inequality, and broad support for redistribution from rich to poor. The needs of children are valued particularly highly, while able-bodied adults are expected to make a fair contribution, either through paid work in the labour market or by caring for dependants. There is strong evidence that European citizens favour ‘participation’ in socially valued activities, and are intolerant of ‘freeriding’ in the welfare state. This would suggest that the public will support measures that help people into work (such as free childcare and activation policies) which also address the adequacy of rewards (for example, measures to narrow the gender pay gap) (Mulgan, 2005).

The second point relates to the importance of public trust in governments and politicians. While citizens in most EU member states do lean towards support for redistribution, there is greater scepticism about whether national governments have the capacity to carry out redistribution fairly and legitimately. An issue that has been inflamed by the 2008 financial crisis concerns tax reform programmes which clamp down on evasion and non-payment of taxes. The evidence suggests that a convincing effort to penalise tax evasion and avoidance would do a great deal to restore public confidence in the capacities of the state. This also suggests that social democrats who rely on collective institutions to pursue their goals cannot afford to let government and politicians slide into public disrepute. Political trust is inextricably intertwined with the pursuit of social justice, and the centre left has to help improve the quality and transparency of public debate (Gamble, 2012).

The third challenge involves using political instruments to help reshape public attitudes and views. It is misguided merely to acquiesce to public opinion, engaging in a ‘race to the bottom’ on income and corporate tax rates; as Taylor-Gooby (2013) makes clear, this might actually serve to harden public attitudes in a negative direction. At the same time, centre-left parties have a responsibility to lead public attitudes, not merely to follow. There is nothing inexorable about trends in society such as individualisation and growing diversity invalidating social justice policies or destroying the basis for collective action. It is important that social democratic parties take responsibility and show that they can reframe public agendas.

All three key challenges are relevant to major debates in contemporary welfare policy, chiefly the future of universalism: a universal welfare state has been one of the core pillars of social justice in Europe since the second world war (Esping-Andersen, 1999). In many European countries, centre-right governments have sought to question the viability of universalism in the wake of the global financial crisis; several arguments have been used to justify the cutting back of universal welfare (Horton & Gregory, 2009). The first argument is the need to reduce government deficits, and therefore to scale back welfare state coverage of major social programmes such as child benefit and universal pensions. The second is perhaps more principled, suggesting that universality involves transferring resources from the poor to the rich, and that targeting resources on the poorest is the best way to help those most in need. It is difficult to justify taxing those on low incomes merely to pay universal benefits to those on higher incomes (Horton & Gregory, 2009).

However, centre-left parties in Europe ought to be cautious about acquiescing to the ideological right’s views about universalism and the welfare state. In fact, the more targeted welfare provision becomes, the less likely it is that services will be of the highest quality, as Richard Tittmuss famously predicted. Countries with higher degrees of targeting tend to be characterised by lower overall spending on the welfare state as a share of national income (Horton & Gregory, 2009). What such arguments disguise is a familiar ideological claim on the part of the right, namely that all forms of state provision create dependency, and that the purpose of government should be to keep spending and tax rates as low as possible.

This is diametrically at odds with social democratic principles: the welfare state was never chiefly concerned with charity or philanthropy, but with the idea of risk sharing and resource pooling: buying services and insurance through the state should encompass the entire population, not only the poor (Taylor-Gooby, 2012). At the same time, Nordic social democracy in particular has always seen welfare as integral to a sustainable model of capitalism: welfare is a source of wealth creation, not merely a drain on resources (Esping-Andersen, 2009). This encapsulates the basic synergy between economic efficiency and social justice: for example, ensuring that talented and highly skilled women can access the labour market entails universal, high-quality and affordable child care coverage for all families. This is a more substantive moral basis for the welfare state than the claim that those on higher incomes should support measures that reduce inequality which breeds social disorder and fragmentation. This claim was at the heart of The Spirit Level (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009), but the argument underplays the extent to which universalism directly benefits the whole of society.

The defence of universalism is about protecting the long-term interests of the poorest in society, as well as reaching out to middle-class voters. A majoritarian welfare state can help to meet the aspirations of middle- and higher-income citizens, as well as preventing poverty among low-income households (Horton & Gregory, 2009). It is important to continue to challenge ideological arguments against universalism, engaging in a battle of ideas not only about the future of the welfare state, but the role of government in a rapidly changing world.

It is also imperative to make the case for universalism in today’s society given the rise of new social risks, increasing wage and income inequality, and the desire for redistribution over the life-course (Taylor-Gooby, 2012). This can help to ease transitions, facilitating individual choices that enhance personal autonomy from caring to lifetime learning, a crucial dimension of social justice. While this chapter has not focused directly on the policy implications arising from these findings, it is worth reflecting on what public attitudes in Europe might say about how best to pursue the social justice agenda alongside welfare universalism:

• Social democrats have to be concerned not only with social justice, but economic dynamism. Support for effective strategies to counter poverty and inequality is strongest where there is confidence that economic growth will be sustained (Carlin, 2013). Social justice and economic dynamism can be reconciled, although it is important to be aware of potential trade-offs.

• Traditional redistributive mechanisms are necessary, but they may need to be modified in the light of structural change. For example, progressive taxation has an important role to play in redistributing resources from rich to poor, but must not compromise economic needs or job creation (Aghion, 2014).

• While policy legitimately focuses on the needs of the long-term poor and excluded, it is important to be concerned with ‘transitions’, in particular the role of active labour markets in enabling people to escape poverty. There should be a strong emphasis on activating labour market strategies since active participation strengthens support for the welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 2009).

• Policies that are designed to help the poorest should also focus on in-work poverty, increasing financial support for carers and ensuring that an adequate structure for the minimum wage is in place across EU member states. Reducing child poverty must continue to have a central place in the social justice agenda of centre-left parties in Europe.

• Policies that benefit more affluent groups are important if they help to consolidate commitment to universalism in the welfare state.

• ‘Gender-sensitive’ policies are crucial, not only to continue improving the economic position of women, but also to provide greater support to parents and young families (Carlin, 2013). Exposing pay differentials between men and women will help to tackle the gender pay gap, backed by anti-discrimination legislation.

• The wealthy and high earners need to be properly incorporated within the obligations and duties of citizenship. Social responsibility must be exercised at the ‘top’ of society, not merely among the most excluded (Miller, 1994). The financial crisis appears to have opened up more space for radical action on pay and taxation.

• Finally, policy in nation states has to be matched by action at the EU level. ‘Social Europe’ has an important role to play, encouraging member states to benchmark progress on key indicators such as reducing child poverty; sharing best practice in solving the toughest challenges, notably long-term unemployment; and evolving new mechanisms such as the structural adjustment fund to mitigate the impact of social exclusion in the worst affected regions of the EU (Liddle & Lerais, 2006). Europe itself has to be a force for greater solidarity and social justice; the UK referendum on future membership of the EU demonstrated the negative consequences of failing to deal effectively with growing inequality and polarisation.

Conclusion

This chapter has argued that while there are inevitably a variety of ideas on which centre-left parties can draw, social democrats should focus on developing a new politics of social justice across Europe. It is essential to bring together an account of the various dimensions of social justice with an informed assessment of the underlying nature of public opinion. Recent research on poverty and inequality has tended to focus on underlying values, rather than examining what drives and motivates particular attitudes. Cross-national comparisons help to illuminate important underlying trends and patterns, while highlighting how particular issues and themes might be reframed in order to support social democratic objectives in an increasingly complex world. It is important to assess the underlying drivers of public opinion in order to build a new consensus for social justice in Europe. If social democrats articulate bold ideas that take account of intuitive public sentiments, they can reshape both institutions and interests, laying the ground for new majoritarian electoral coalitions. The answer, as the former SPD leader Willy Brandt once observed, is not to abandon traditional values but to ‘dare more social democracy’.

Whatever ideas social democracy assembles at the national level, however, it needs to confront not only the growing challenge to nation states and the fundamental weakness of pursing a ‘national road to socialism’, but the growing counter-reaction to supranational politics, especially at the level of Europe. This dialectic between nation state politics and liberal internationalism is assessed in the next chapter.

Notes

1. J.M. Keynes, Essays in Persuasion, London: 1931.

2. See Colin Crouch, The Strange Non-Death of Neo-Liberalism, Cambridge: Polity, 2011.

3. https://milescorak.com/2016/05/18/the-winners-and-losers-of-globalization-branko-milanovics-new-book-on-inequality-answers-two-important-questions/

4. https://milescorak.com/2016/05/18/the-winners-and-losers-of-globalization-branko-milanovics-new-book-on-inequality-answers-two-important-questions/

5. See R. Liddle & F. Lerais, ‘Europe’s Social Reality’, Bureau of European Economic Advisers (BEPA), Brussels: European Commission, 2006.

6. David Miller, Principles of Social Justice, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1994.